Makala Skinner, Research Associate, WES

Historically a country that sends its students abroad for higher education, India is seeking to rebrand itself as a higher education destination. Within the past year, India has invested substantial resources in a series of initiatives and agreements to bolster international student enrollment and improve the quality of Indian higher education institutions (HEIs). These include the Study in India [1] campaign, which seeks to quadruple the country’s current number of inbound students by the year 2023 [2]; and the Institutions of Eminence [3] program, which will venture to put 20 Indian HEIs within the top 500 world rankings.

India is also in the midst of planning a series of agreements with countries [4], primarily in Asia and Africa, to mutually recognize one another’s education credentials. Though India’s higher education system, one of the largest [5] in the world, has significant assets, it also faces critical challenges. These must be addressed for India to become a repository of higher education excellence [6] within the region.

India as a Source Country

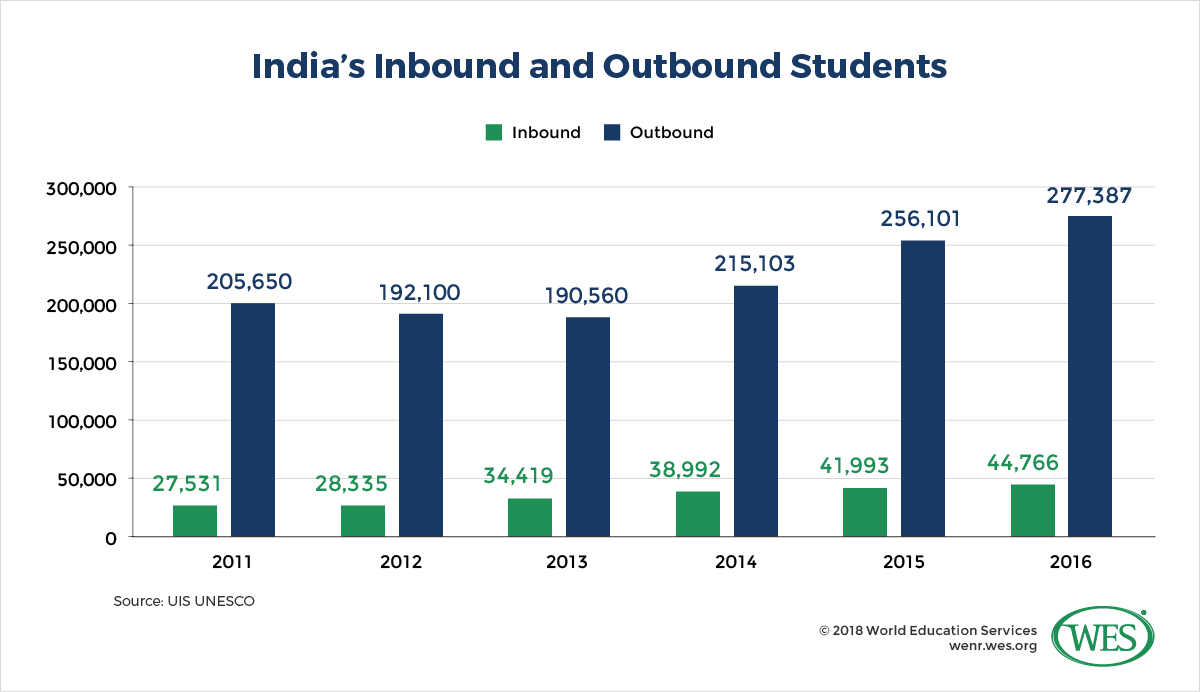

India is an important player in the field of international higher education as a source of international students; in fact, India sends [7] more students abroad than any other country except China. In 2016, more than a quarter million Indian students studied internationally, compared with only 44,766 [8] students who arrived in India from abroad. The number of both outbound and inbound Indian students has steadily increased [7] since 2000, except for a brief dip in outbound students from 2011 to 2013.

According to UNESCO Institute of Statistics [8], 76 percent of Indian students pursuing their tertiary education abroad traveled to five countries in 2016: the United States, Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and New Zealand. The U.S. alone accounted for 40 percent of all outbound Indian students. These numbers have begun to shift, however, in part because of changing student visa policies in several countries. In 2017, the U.S. instituted stricter visa policies and saw a 28 percent [9] decline in F-1 student visas issued to Indian students.

The U.K [10]. recently made changes to ease the visa process for international students from 26 countries; however, it omitted India. There was a significant backlash [11] to this move, which is likely to lower even further the number of Indian students studying in the U.K., a number already less than half what it was six years ago.

And Australia recently eliminated its 457 visa category [12], which had allowed international professionals to work in the country for up to four years; the termination of this visa is disproportionately affecting Indians.

Canada [13], on the other hand, streamlined its visa process for four countries, including India, and reduced its processing time from 60 to 45 days in 2017; this produced a 58 percent increase in visas issued to Indian students.

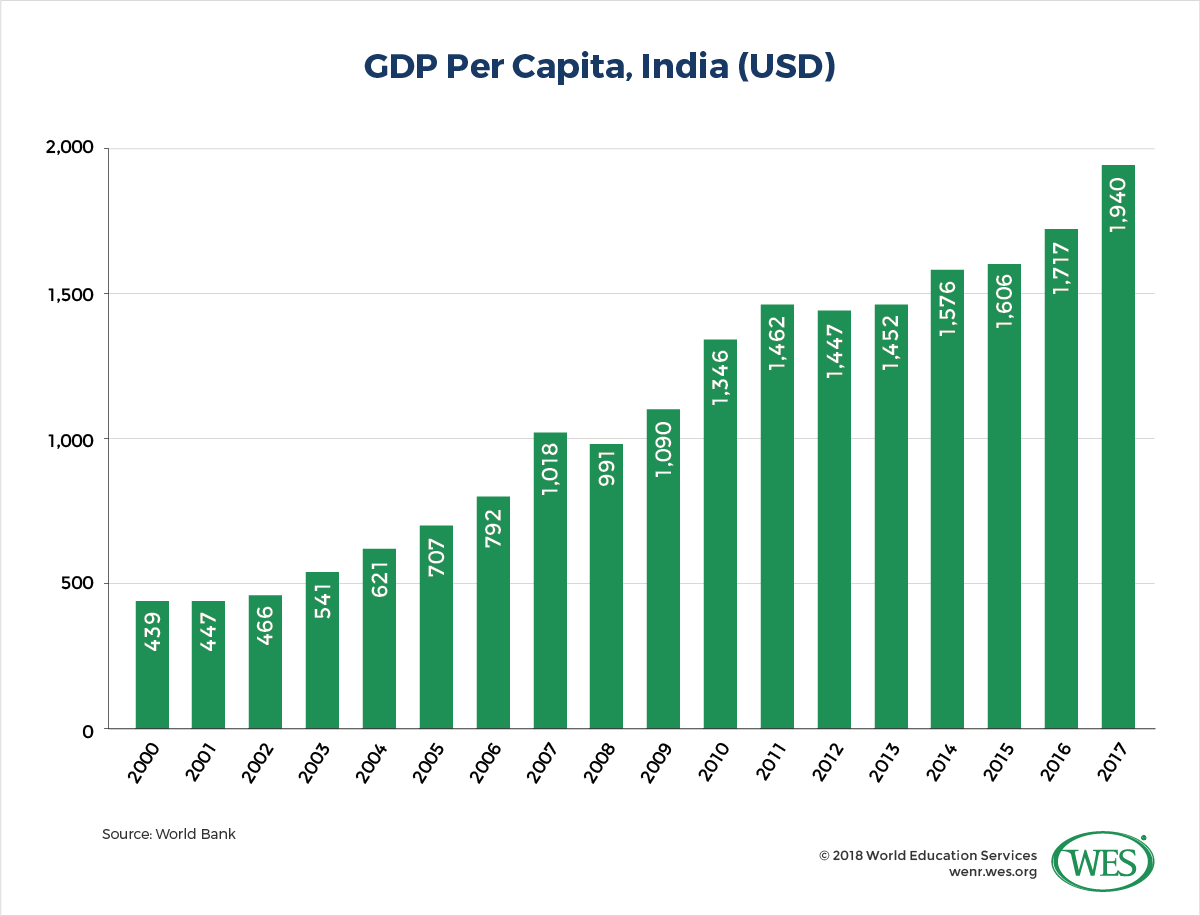

The marked difference between inbound and outbound students shown in the graph above is partly explained by the growing Indian economy, the country’s burgeoning college-age population, and the uneven quality and limited capacity of its HEIs. India’s GDP [15] has consistently grown since the mid-1980s and has rapidly increased over the past 15 to 20 years. In conjunction, Indian students have pursued higher education in greater numbers: In the 2016–2017 school year, 35.7 [16] million were enrolled in higher education—this number makes up just one-fourth of India’s total college-age population.

While a growing economy and increased resources have allowed many students to continue their education, the educational quality of Indian HEIs is inconsistent and their capacity is limited. In the Times Higher Education World University 2018 rankings [18], the highest ranked Indian HEI was only 251 on the list. As the demand for quality higher education surged among Indian students over the past two decades, the supply of such institutions could not keep pace, resulting in a groundswell of Indian students going abroad to further their studies.

In addition to their inconsistent quality, Indian HEIs lack the capacity to provide seats to a sufficient number of national students. By 2020 [19], India is projected to have the largest college-age population in the world; even now, competition [20] among Indian students for admission, especially to higher ranking institutions, is fierce.

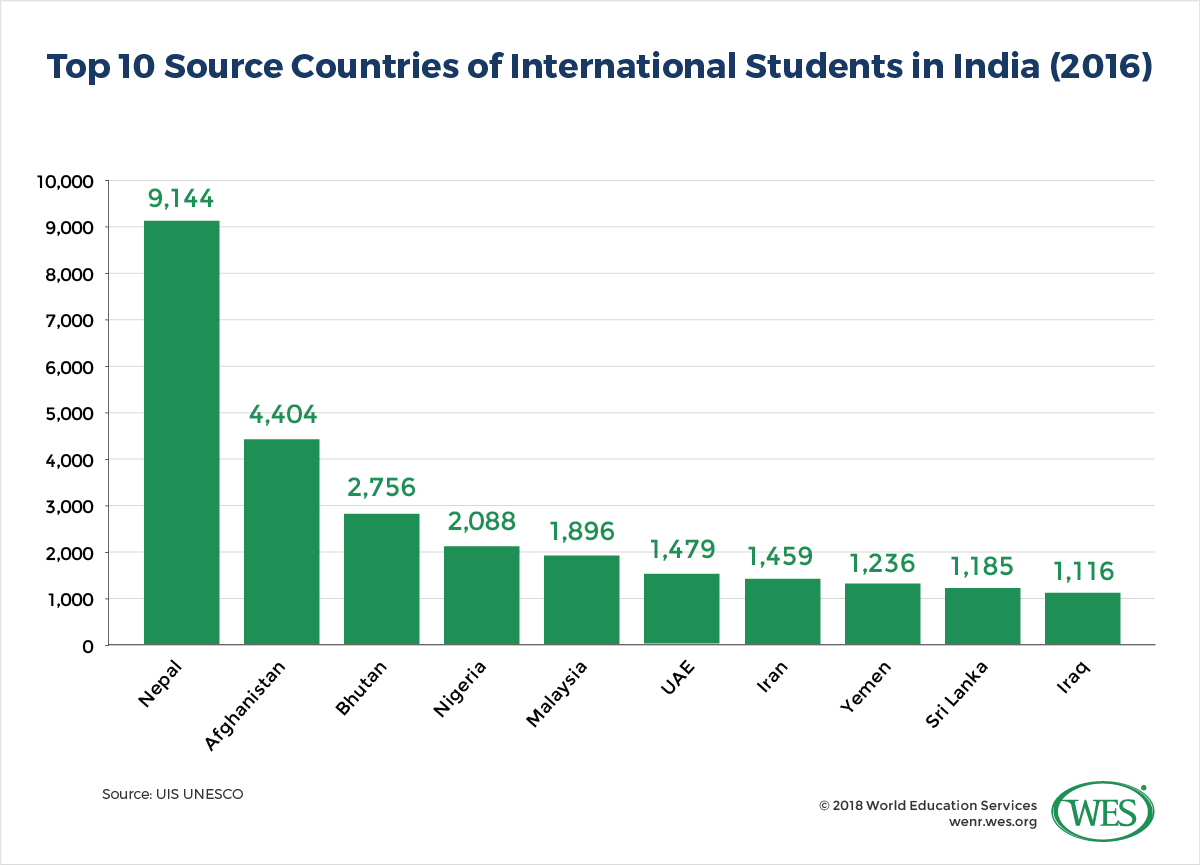

The variability of Indian HEI quality likely accounts, in part, for the low percentage of inbound students as well. International students who do select India for their education most commonly hail from the region. The top three sending countries to India are Nepal, Afghanistan, and Bhutan [16], and account for more than one-third of the total number of international students in the country.

Recent Actions

To address the dearth of foreign higher education learners in India, the Indian government has launched a series of efforts to improve Indian HEI rankings and appeal to greater numbers of international students.

Study in India

The most recent initiative is Study in India, rolled out in March 2018 and run by the Ministry of Human Resource Development [2] and the Ministry of External Affairs. The goal of Study in India is to increase the number of international students from the current 44,766 to 200,000 [2] by 2023.

The initiative reserves 15,000 [22] additional seats for foreign students within participating HEIs; the newly created seats will be in addition to the current number of spots available for domestic students. The Indian government has issued 1.5 billion [23] rupees, the equivalent of approximately USD$2.2 million, to promote the campaign over the next two years.

Chief among the reasons that India is endeavoring to become an international higher education hub through Study in India is the country’s aim of increasing its soft power in the region. Study in India will focus recruitment primarily on nations in proximity to India; they were selected strategically with aiding India’s regional diplomacy in mind. Additional objectives of the campaign include doubling India’s “market share of global education exports [23],” bringing it up to 2 percent; and improving the quality of education at Indian HEIs.

To attract international students, India is striving to become an affordable [24] education destination within the region. Depending on their SAT scores [25], most admitted international students will receive some level of waived tuition [23] fees, ranging from 100 percent for the top quarter to 25 percent for the second to lowest quarter. Students in the bottom quarter will not receive a tuition fee waiver. The Study in India website [26] describes other financial help available such as the General Scholarship Scheme [27], which is open to students from roughly 60 countries.

Institutions of Eminence

Study in India is running in tandem with the country’s Institutions of Eminence [3] strategy, also launched earlier this year. Its goal is to raise 20 Indian HEIs (10 public and 10 private) to the top 500 in the world within the next 10 years. The initiative’s long-term goal is to have these schools included in the top 100 of the world rankings.

The strategy allows institutions greater autonomy and flexibility to recruit international faculty, admit more foreign students, and form strategic partnerships with top world-ranking institutions without, among other things, having to seek the approval of the University Grants Commission. The government is investing liberally in the strategy: Selected institutions will receive 10 billion rupees, approximately USD$148.2 million, over just five years.

Country Agreements

India has spent the past several years laying the foundation for both Study in India and Institutions of Eminence by strengthening its educational relationships with other countries and encouraging greater international student enrollment.

For example, India has enjoyed a long-standing relationship with countries that make up the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN [28]); the ASEAN-India Student Exchange Program [29] was started in 2008. The program seeks to foster relationships and cultural appreciation between India and the ASEAN countries (Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam) by bringing ASEAN students to India for short-term trips. The value in this relationship can be seen in the Vietnamese ambassador [30]’s recent recommendation that Vietnamese students pursue their education in India.

In addition, the country, a member of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), has reserved seats and abridged requirements for students from the other SAARC [31] countries (Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka) through bilateral agreements. Two years ago, the Indian government created 10,000 [32] new spots for international students at the elite Indian Institutes of Technology and prioritized eight countries, five of which are members of SAARC.

And in April of this year, French and Indian dignitaries signed a Memorandum of Understanding [33] agreeing to recognize academic credentials between their countries. India has plans to recognize the higher education degrees of 30 [4] other countries as well, primarily in Africa and Asia.

Indian HEIs: Assets and Obstacles

As India seeks to recruit greater numbers of international students and to improve the quality of the education it has to offer them, several factors deserve consideration. India’s current position is one of both advantage and disadvantage, the latter of which will need to be addressed for the country to succeed in its goal of becoming a higher education focal point within the region.

Assets

Indian HEIs possess many compelling characteristics as educational destinations. English [34] is the primary language of instruction at Indian universities; and a university education is available in India at much more affordable [24] tuition rates than those of universities in the U.S. or Canada. In addition, procuring a student visa [22] to India is easier for international students under the Study in India program—of particular importance at a time when some nations, including the U.S., are introducing increasingly restrictive student visa policies [35].

India also benefits from having a substantial higher education [6] system situated within a flourishing economy. In fact, the country currently has the third-largest [5] network of HEIs across the globe. While not all of these schools will partake in the programs described above, the multitude of institutions does offer many locations for international students to enroll in. With the exception of India’s top-tier institutions, competition [36] for offers of admission is likely to be less than in other English language higher education destinations.

Obstacles

While Indian HEIs have appealing assets, they also face numerous structural challenges. India currently does not have a system [31] in place for recognizing international credits or pathway education, making it challenging for students who attended a non-Indian school to transfer credits to an Indian institution. To date, no explicit plan has been devised to address this gap in the system.

As previously mentioned, the quality of education provided at Indian HEIs is variable [6], and only a select number of institutions are known internationally. Institutions of Eminence, designed to address education quality at HEIs, has seen multiple setbacks [37] at the outset, including concerns about the selection process and timeline delays. Nor does the Indian higher education system have a central webpage [38] that provides pertinent information about each institution and the types of programs and courses offered, making it difficult for international students to learn about their options.

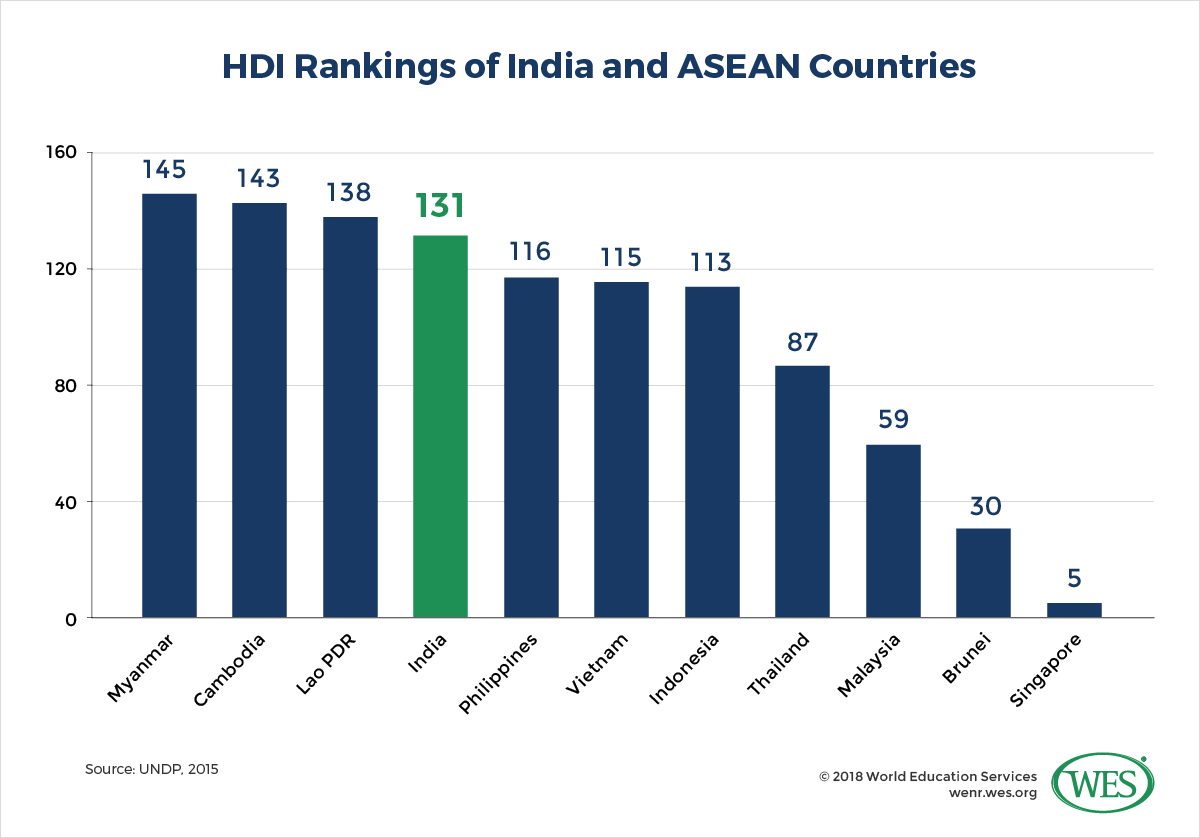

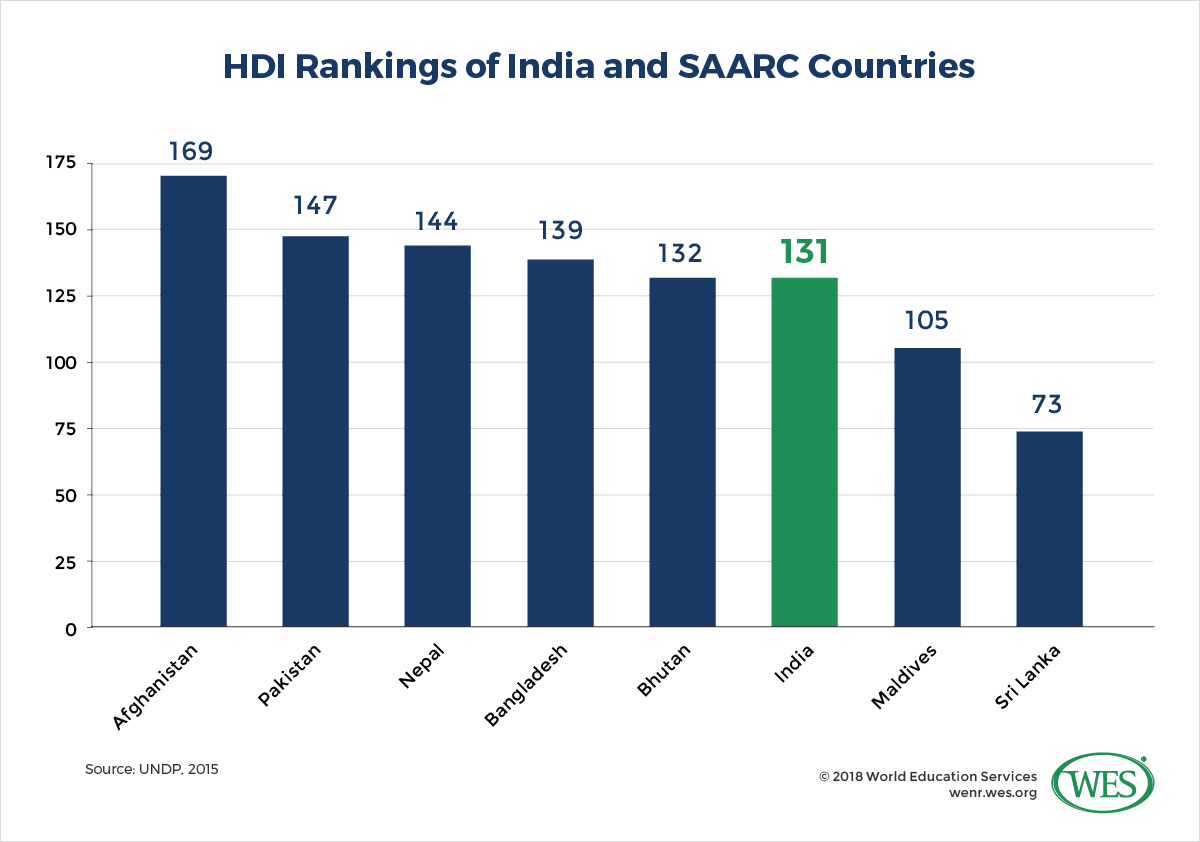

In addition to educational quality concerns, HEIs face accommodation challenges as well. There is a dearth of comfortable student [38] housing and adequate facilities, which will be costly to address. Outside of campus housing, the quality of life in Indian cities at large is lower than that of many others: A 2018 survey [39] measuring quality of life in cities around the world found that not one city in India was rated within the top 100; its highest ranked city was positioned at 142 out of 231. On the Human Development Index [40], India ranked 131 out of 188 in 2015 (the most recent available data), putting it in the bottom 30% of countries in the world. Though this position is comparable to those of other nations in the region and is higher than the rankings of several SAARC countries, it still lags significantly behind the majority of ASEAN countries. Discrimination [38] toward some ethnicities is a further cultural and social challenge and may cause international students to worry about their safety.

Compounding these obstacles, competing countries in the region are much further along in raising standards and recruiting internationally. China [34] has been actively investing in its higher education system for the past 20 to 25 years, as well as creating incentives for international students and staff. These efforts have now made China the third-largest [43] destination country for international students.

Items to Consider

Reaction to India’s investments in international education has been mixed. There has been some backlash [20] to the new initiatives, with those who oppose the programs raising concerns that the government has gone too far to promote international education, and that it has done so at the expense of domestic students. Others see the investment as a potential return to India’s historical [19] position as an education leader, and still others feel that the initiatives are a good start but do not go far enough [44].

The results of India’s expenditures to improve the quality of its higher education system and recruitment of foreign students are difficult to predict. If India succeeds, it has the potential to shift the current international higher education landscape over the next decade. Investments in international education may lead to a more robust higher education system which would attract not only greater numbers of foreign students, but also greater numbers of Indian students, who would stay and pursue their education in India as well. Demand for quality HEIs is a primary driver of Indian outbound mobility; should that demand begin to be met in-country, the percentage of Indian students going abroad may decrease over time.

On the other hand, though the government has been aware of domestic students when structuring these programs—as previously noted, the Study in India campaign provides 15,000 extra seats [6] to international students, which will not decrease the number of seats available to Indian students—investing so much in international education may still divert financial resources away from domestic students. For example, international student tuition waivers are to be doled out from existing resources at the university level rather than from additional funds. These international waivers may inadvertently decrease domestic student scholarships and, perversely, prompt Indian students to study abroad.

Despite the mixed reaction and uncertain consequences, one thing remains clear: India’s HEI system is seeing major changes and is poised to send significant ripple effects throughout student mobility in international higher education. What those effects will look like, however, remains to be seen.