Makala Skinner, Research Associate, WES

The use of commission-based agents to recruit international students has increased dramatically within the past few years. Between 2011 and 2016, the percentage of schools using agents in the United States nearly tripled, jumping from 11 percent to 30 percent, according to an American Council on Education [1] report. As of 2017, an estimated 20,000 [2] recruitment agencies operated worldwide.

WES neither endorses nor discourages agent use. The increase in institution-agency partnerships in the U.S. in recent years, however, merits an examination of both the positive and negative aspects of working with recruitment agents.

Although WES previously conducted research on student experiences with agents [3] and educational consultants, missing from the discussion was a look at the rationale that impels HEIs to engage agents’ services, as well as HEIs’ perspectives on recommended practices for working with them. For this reason, WES interviewed 10 institutional representatives from U.S. higher education institutions (HEIs) that have relationships with agents and asked them about their perspectives on the benefits and drawbacks.

We have concluded that care is warranted when choosing commission-based international recruiters. For institutions that do engage with recruitment agents, this article will provide best practices for engaging and developing successful partnerships and reducing risk exposure.

Agent Use: A Global Practice Comes Home

The use of international agents has been hotly debated. Opponents cite examples of corruption and unethical practices including pressure tactics, fraudulent documents, providing inaccurate information, and the potential to harm both students and institutions. Proponents note that agents have contextual knowledge, speak local languages, can help make student recruiting less costly and resource intensive, and have the potential to boost international student enrollment.

International recruitment agents are commonly used among HEIs in many countries, including Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom [4]. Their use in the U.S., however, has historically been a point of contention. Agencies—the third-party partners that recruit students abroad on behalf of institutions—typically receive commissions for the students they send. Opponents of agent use have largely been concerned with the possibility of unethical practices [4], such as agents providing inaccurate information to prospective students, steering students toward particular schools for their own financial gain, charging both the students and the institution, or tampering with applications. Unscrupulous agents can cause hardship for students as well as harm the reputation of institutions. One such example took place in 2016 when Western Kentucky University suspend [5]ed at least 25 out of 60 Indian graduate students recruited at a rate of USD$2,000 per head [6] by an agent based in India. The students lacked the necessary academic prerequisites.

On the other hand, reputable recruitment agents provide valuable services to students and institutions alike. Those favoring recruitment agencies have cited [7] agents’ permanent presence in-country and knowledge of the context, education structure, and languages as positive contributions to recruitment that offer more comprehensive support to students and yield higher enrollment rates.

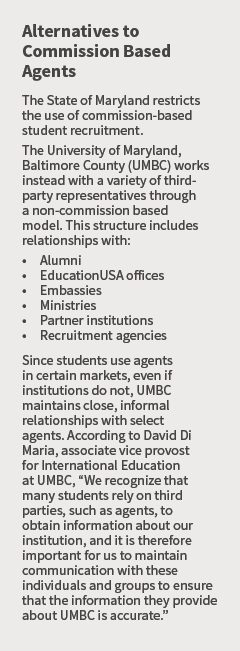

Prior to 2013 [3], the ethical guidelines of the National Association for College Admission Counseling (NACAC [8]) stated that using recruitment agents to enroll international students was unethical. Though NACAC’s standards are not legally binding, failure to comply results in professional consequences [9] such as being excluded from recruitment fairs. However, five years ago NACAC’s stance on agents changed in a 152–47 [4] vote, and the organization lifted its ban on recruitment agencies. NACAC’s Report of the Commission on International Student Recruitment [8] stipulates that HEIs that do engage with recruitment agents must ensure (1) institutional accountability, (2) transparency, and (3) integrity.

While the percentage of U.S. schools using commission-based agents increased to roughly 30 percent as of 2016 [10], this percentage is small in comparison with that of other countries. Nearly three-quarters of international students attending Australian universities [11] used agents in 2016, and more than 92 percent [12] of HEIs in the U.K. used international recruiters in 2014. NACAC noted in its deliberations, however, that other countries are better able to use recruitment agencies ethically in part because of those countries’ more centralized higher education systems and stricter regulations.

Within the U.S. context, recruitment agents have historically had a poor reputation. John Deupree, former executive director of the American International Recruitment Council (AIRC), asserts that some negative perceptions of agencies are a result of unrealistic expectations on the part of institutions. “Agencies are as eager to be a professional, knowledgeable partner in this process as the institutions are, and that’s often not appreciated,” Deupree says.

Regardless, the U.S. view on the use of international agencies is shifting, and more institutions are engaging in productive relationships with agents. According to a WES survey of HEI representatives, 52 percent [13] of respondents plan to increase agent use in the 2018–2019 academic year.

Why Higher Education Institutions Employ Agents

Circumstances leading to agency partnerships vary by institution. While some schools meet agents through education fairs and develop relationships organically, others begin intentionally seeking agency partnerships as part of their strategic plans. John Jay College of Criminal Justice, a City University of New York school, began working with agents in 2015 when its international admissions department developed a comprehensive recruitment strategy.

“Signing agents and dedicating more money to recruitment of international students is only one piece of the puzzle,” says Eli Cohen, John Jay’s deputy director of International Student Recruitment & Marketing. Salma Benhaida, director of International Recruitment, Admissions & Sponsored Student Services at Kent State University, echoed this sentiment, stating that the school began using agents to add to its recruitment mix. According to Benhaida, making use of diverse strategies—including traditional recruitment, social media, and agencies and other third-party partners—is important for recruiting strong cohorts of students. Using international recruiters is one strategy of many.

Just as multiple recruitment strategies are vital, so too is tailoring them to individual markets. In certain countries, students and parents expect to use agents to help complete applications or visa processes. For an institution to penetrate these markets without agents is difficult. Schools should examine each region or country and define the best strategies to find students within that context. Benhaida notes that China, India, Bangladesh, and Saudi Arabia are all markets that have a critical saturation of students who use agents, though China has begun to see a shift at the undergraduate level: Parents and students are relying more on secondary school guidance counselors rather than agents to assist with the application process.

Institutions working to recruit international students often have small international marketing and recruitment teams and face budgetary constraints that limit travel. Working with agencies began as a way to address, in part, these capacity challenges. Since schools typically pay commission only upon student enrollment, partnering with agents is often seen as a relatively low-risk strategy, provided that institutions develop strong relationships with these partners and use best practices in vetting and assessing them.

Positives of Working With Agents

Several of the institutional representatives who spoke with WES stated that institutions that are highly selective and work with well-vetted agents receive numerous benefits from these partnerships.

Increase enrollment

The primary benefit of employing recruitment agents is that they help to bring in students, particularly qualified students. At Wichita State University, approximately 30 percent to 40 percent of the total international student body is enrolled through agencies, and at Southern New Hampshire University, about 65 percent of graduate students are recruited this way. While agents may be used for undergraduate students as well, they are particularly effective in recruiting graduate and ESL students. Since many prospective ESL students do not speak English yet, having someone recruiting in the local language is an advantage.

Extension of recruitment team

Institutional representatives noted that agencies act as an extension of the recruitment team and allow schools to be “on the ground” all over the world at all times. Not only does this presence allow schools to reach a larger student population and market, it also increases contextual knowledge. Most third-party partnerships, including recruitment agents, speak the local language, understand the culture, and often have contacts within the local education system. The ability to be on-site long-term helps schools navigate around potential pitfalls that can arise from only being in-country a few days a year.

Market intelligence

From a country-strategy standpoint, agencies can provide institutions with on-the-ground intelligence of the market by relaying what students and parents are thinking. Good agents are able to provide information on market shifts that schools may otherwise not be aware of. This kind of information can guide institutional strategy within a region. For example, market intelligence can identify which countries or cities have a large population of students interested in a particular program the school offers. Likewise, agents are useful when an institution is working to establish a presence within a market.

“We have a couple of markets where we’ve never had activity in the past, and then through a few good key agents, we’ve been able to start building a funnel and see several students come through,” says Kirsten Feddersen, associate vice president of International Programs at Southern New Hampshire University.

Negatives of Working With Agents

While institutions may receive various benefits through their partnerships with recruitment agencies, there can be significant downsides to these relationships as well.

Fraudulent documents

Forged documents and visa fraud can be considerable challenges when working with unethical agents, although the select representatives we interviewed for this article stressed that these were rare occurrences and not unique to agents.

“Whether you’re talking about domestic students or international students, all institutions face instances of fraudulent documents,” says Bryan Gross, vice president for Enrollment Management and Marketing at Western New England University (WNE). “We have absolutely detected fraudulent documents from students who have not come from agents, and we have detected fraudulent documents from students who have come from agents.”

Feddersen notes as well that receiving fraudulent documents does not necessarily mean the agent is being deceitful; however, when fraud is caught by the institution and not by the agent, it reveals agency ineptitude. Ross Jennings, senior director of International Education at Green River College, notes that when doctored documents do come through, they are from new agents and virtually never from long-standing agency relationships.

In the broader international context, many instances of agent fraud have been reported on in the last decade. Authorities in Australia and New Zealand—countries which use agents at a higher rate than that of the U.S.—have uncovered significant fraud by agents in countries such as India, China, and the Philippines. In the first half of 2016, immigration authorities in New Zealand, for example, rejected more than 50 percent [14] of student visa applications from India because of fraudulent documents, about half of them submitted by agents. It is important to note that the agents in question were unlicensed and that some schools participated knowingly in the corruption to increase student enrollment. New Zealand’s Immigration office in Mumbai between 2014 and 2016 identified 265 agents [15] who submitted applications that included fraudulent documentation, including several high-volume agencies, and found that fake bank statements, for instance, were used in student visa applications with significant frequency [16].

Justin Alves, a New Zealand immigration manager, told PIE News in 2016 [16] that “the depth and breadth of penetration” of agent fraud was “concerning. So far there has been no agent we’ve looked at which hasn’t been using it, to some extent or another.”

Munish Sekhri, vice president of Licensed Immigration Advisers NZ, echoed this [15] in the New Zealand Herald, noting that unlicensed agents “do anything from arranging fake documents, providing fraudulent funding, and even an impostor service” (that is, posing as applicants in immigration interviews).

Australia, which uses a high number of recruitment agents and paid approximately USD$194 million in commissions in 2015, has in the past faced similar challenges. WENR Editor Stefan Trines mentioned in a previous article that, in 2011, the Australian government suspended “more than 200 [17] unscrupulous agents from India, China, and Australia from submitting visa applications because they submitted ‘fraudulent information in support of a student visa application.’ In one instance, a university audit of a corrupt Indian recruiter found that 95 percent of the applications submitted by the agent were fraudulent. In China, a majority of prospective international students reportedly use agents. Some of these [agents] are, as the Australian government put it [17], ‘sole traders with not much more than a catchy title, a string of promises and a mobile phone,’ eager to ‘clean up’ essays, falsify records and submit fraudulent documents for economic gain.”

[18]Lack of response

[18]Lack of response

Among the institutions included in our interviews, initial institutional efforts to establish a relationship and train agents did not always pay off. “Sometimes we put a lot into the relationship up-front and never see any students,” Feddersen says. Gross echoes this, stating that some agents do not invest in the partnership to the degree that the institution does. This lack of effort can be seen in a failure to respond to emails, lack of productivity, sending unqualified student applications, a failure to absorb trainings, and a seeming lack of knowledge about the institution.

Misrepresentation of the institution

A lack of understanding institutional goals and unique qualities can lead to a misrepresentation of the school brand when relaying information to prospective students. In some cases, agents misunderstand school programs or policies and convey incorrect information to students. In other cases, the agency intentionally misleads the student. For example, one interviewee noted instances where students expected scholarships that agents had promised that the school had never offered.

Structure of Institution-Agency Relationships

The most common type of institution-agency agreement is commission-based and contingent upon students enrolling in the school. These agreements usually take the shape of a formal contract that lists in writing the obligations of both the institution and the agency. Contracts are often for two or three years’ duration; some institutions issue shorter-term, 18-month contracts as a trial period when working with new agents. The number of agents taken on by schools ranges considerably from as few as 10 to 15, to as many as 900; the 900 agents in contract by one institution is a distant outlier, however. The most commonly cited number of partnerships by the HEI representatives that spoke to WES fell between 25 and 50.

Advice From Practitioners

- Start small and develop relationships.

“Keep a close relationship with a small number of agencies,” advises Fai Tai, associate director, International Student Recruitment at WSU. “If you are able to go and visit those agents and give them training … it helps them do their job.” Look at agency partnerships as ongoing relationships that need to be nurtured. The most positive outcomes stem from agents with whom institutions have strong, personal relationships.

- Follow up and maintain the relationship after the contract is signed.

Agencies work with many institutions, and they promote the schools that make an effort to be promoted. They put more time and effort into institutions that pay attention to them and provide support.

When institutional staff turns over, make sure the agency relationship is handled thoughtfully. Deupree relayed that agencies would invest significant time and effort to help an institutional representative learn the marketplace and the kinds of students that the agent could provide, only to have someone new take over the role: “Agents would get frustrated … [because] after a year of sort of reverse training the person, somebody else would move into the position with no context or knowledge and no one told the agent. The continuity wasn’t there.”

- Effectively communicate what sets your institution apart.

It is crucial for schools to articulate what sets them apart in a global market and for this message to be consistent internally, as agents may speak with multiple school representatives.

Clear communication of school programs assists with brand recognition and brings international visibility to universities as well. This greater visibility can be particularly useful for community colleges, non-highly ranked universities, and institutions that have limited international name recognition. For example, Jennings explained, the concept of a 2+2 transfer program between community colleges and four-year institutions is not well-known in many places overseas. Agents who can communicate what the school offers help to educate students and their families about educational options.

- Consult important resources in the field.

In the U.S., the higher education system is locally driven and schools are largely autonomous. Because of this looser structure, independent organizations have developed as a way for professionals to come together and determine standards of practice, providing guidance to HEIs. The need for a viable authority on recruitment agents gave rise to AIRC [20], the body of professionals that designed an agency certification process.

AIRC [21]’s resources includes useful information on contracts, guidelines for vetting agencies, an annual conference, and tips for working with agents. Another to consult is NACAC’s “Statement of Principles of Good Practice: NACAC’s Code of Ethics and Professional Practices [22].”

- Put proper infrastructure in place.

Effectively supporting agency recruitment requires training admissions counselors in how to communicate with agents and keep them informed. Encourage fruitful results by investing time in training agents and inviting them to visit campus when possible. The more support you provide to your agents, the more effective they will be at their job.

Kent State has a newly created position of International Agent Coordinator, which, according to Benhaida, has been enormously helpful in organizing information, conducting onboarding trainings, paying commissions, and acting as a focal point for all agent-related communication. With this new position the university created a database of all its agents that includes key information such as contract expiration dates, training times, communication, and trainings.

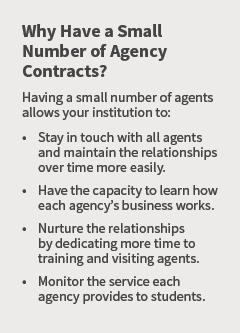

- Contract with a manageable number of agencies.

It is likely not feasible for an office of one or two persons to develop 50 productive relationships within the first year. Taking on too many agents too quickly may result in a lot of work and no students. Managing agency relationships well is resource-intensive. It requires training, ongoing communication, follow-up, assessing productivity, and paying commissions, among other things. When a school takes on too many agents, it does not have the resources or capacity to adequately manage all of them.

- Rigorously vet new agents.

Many institutions, such as John Jay and Western New England University, first look for AIRC certification when vetting new agents. California State University, Long Beach selectively works with uncertified agencies because some smaller agencies are high quality but find certification cost-prohibitive.

![A quote from Jeet Joshee, the Associate Vice President of International Education and Global Engagement at CSU, Long Beach and AIRC President, who says: "Even before [I became AIRC's president], we always looked for AIRC certification because it brings with it a certain degree of quality standards already met."](https://wenr.wes.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/WENR-1018-Institutional-View-Agents-5.png) [24]Have agents complete an application or questionnaire. Some schools, such as Wichita State University, keep their form available online, while others, such as Kent State, prefer to send the application only to agents in a target region. At the University of Bridgeport, the questionnaire solicits information on the agency’s history, its legal standing, and its business structure.

[24]Have agents complete an application or questionnaire. Some schools, such as Wichita State University, keep their form available online, while others, such as Kent State, prefer to send the application only to agents in a target region. At the University of Bridgeport, the questionnaire solicits information on the agency’s history, its legal standing, and its business structure.

In some cases, the University of Bridgeport works with an agency for a trial period—without a contractual agreement. During this period, the institution develops a relationship with the agency and examines student performance and how well the agent adheres to procedures, among other things. Similarly, Southern New Hampshire University issues a shorter contract as a trial period for agencies that have limited experience.

Check references and, where possible, visit agency offices. The institutional representatives we spoke with were nearly unanimous in saying that reference checks are the most valuable vetting tool.

- Continually assess the quality of current agents.

Institutions look at numerous factors when assessing current agents, including:

- the number of applications sent

- the quality of students sent

- agency professionalism

- representation of the institution

- adherence to institutional instructions

Institutions manage this process in various ways. Southern New Hampshire University bases its contract renewals partly on observations of which agents increase institutional workloads without increasing student yield and vice versa. Green River, on the other hand, issues “report cards” on its agents every six months. They include student success factors, such as how long their students have stayed at the school and the students’ GPAs. Similarly, Western New England has a formal annual review process.

Kent State has an Agent Review Committee that meets monthly and reviews agency contracts that are about to expire; it looks at whether agents have sent students, if those students enrolled, and if they are making good progress toward their degree, among other things. Other HEIs visit agency offices abroad to meet the managers and counselors in person, view their business processes, and better understand the quality of service being provided to students.

Elicit feedback from key stakeholders, namely, admissions counselors and students. Admissions counselors often interact with agents’ work on a daily basis and are able to provide information on student application quality and agency responsiveness. Likewise, international students themselves provide insights into agency quality. For example, at the University of Bridgeport, institutional representatives interview students about their experience prior to arriving at the university, and to see if the school was accurately represented.

If an agency produces few or no students, talk with the agent to find out how your institution can help. Depending on the agent’s response, determine whether or not to extend the contract. At Western New England, any agency not producing students but actively engaging with the institution may be retained for continuity in branding.

In rare cases—such as when an agent repeatedly conveys misinformation to students, allows fraudulent documents through, or sends unqualified applicants—institutions should terminate their relationship. Schools should first look at the institutional side of the partnership and determine if the school has failed to adequately train the agents or provide enough support for them to do their job well.

- Trust your gut.

The relationship and personal connection you have with agents is critical to the success of the partnership. “I’ve had meetings with agents where I had the sense that they were giving me empty promises and didn’t really understand the type of institution I was representing ….” Feddersen notes. “And then I’ve met other agents where I felt it was a great match right away—I liked this person, they seemed genuinely concerned about the students, I could see myself working with them—and usually those are the relationships we’ve seen flourish the most.”

- Be strategic.

Speak with institutions that are similar to yours and see which agencies they have had success with. Reach out to these agents and if appropriate follow a model similar to your colleagues’.

Remember that agents are only one piece of international recruitment. As Steven Boyd, director of International Admissions at the University of Bridgeport, says, “In order for universities to be successful in international recruitment, there’s not just one thing that they can do or should do well, they need to do many things well. We have a number of different channels that we use, like many universities here in the U.S., to recruit students. Agents are just one of them.”

- Hire internal staff appropriately.

Agencies require effort, and effort requires staffing. Like any strategic business decision, it is important to make sure your institution has the right people in place and that you are prepared to spend three to five years building these partnerships. “You’re managing multiple complicated business relationships across cultures,” Deupree points out. “There are people at the vice presidential level who struggle with this, so you have to put [people] in these positions who understand what they’re getting into from the beginning.”

Looking Ahead

The U.S. higher education community has shifted in how it views and works with international agents. In 2013, more than 60 percent of admissions directors surveyed by Inside Higher Ed believed “that agents play a direct role in helping international applicants fabricate parts of their applications [25].” Since that time, NACAC has changed its stance on working with agents—in conjunction with agency certification processes, greater checks and balances, and pressure to maintain or increase international enrollment numbers—making the practice more acceptable than it was just a few years ago. Many institutions that manage agency relationships responsibly have found international recruitment agents to be an effective strategy in enrolling international students.

Agency partnerships are likely to take on even greater importance as HEIs look for ways to bolster international student recruitment [26] in the current political environment [27]. The Institute of International Education’s widely cited 2017 snapshot report [28] showed a 6.9 percent decrease in new international enrollment from the previous year, with public universities bearing the brunt of this decline with an 11.3 percent drop. As more HEIs incorporate agents [26] into their long-term strategic recruitment plans, institutions should be mindful of best practices to guard against fraud and work with agents both ethically and effectively.