Stefan Trines, Research Editor, WENR

Since its inception in 1999, the Bologna Process has been framed in terms of historical superlatives. It’s worth noting that the standardization and harmonization of education systems is a recurring theme in contemporary history. Pakistan, for instance, is currently debating the creation of a uniform, nationwide school system to finally overcome prevailing discrepancies in education standards between its disparate provinces [1]. UNESCO’s Arusha Convention [2] on the Recognition of Qualifications in Higher Education in Africa called for the coherent evaluation and cross-border recognition of degrees across the continent as early as 1981.

That said, the European Bologna reforms marked a truly extraordinary undertaking. The harmonization of education systems among a large number of sovereign states was a groundbreaking, transformative process on an unprecedented scale.

To some extent, this synchronization of educational structures was a logical consequence of economic integration and the creation of a single borderless market within the European Union (EU). Differences between education systems and the lack of mutual recognition of academic qualifications constituted an obstacle to deeper economic integration, just like the absence of a common currency.

But the Bologna Process also set a precedent that transcends European integration. Not only did 48 sovereign countries—including non-EU member states like Russia and Turkey—commit to harmonizing their education systems, but the reforms also inspired countries in other world regions to pursue similar reforms [3].

As a result, regionalization in higher education has now become an almost common phenomenon. The Association of South East Asian Nations, for instance, is currently trying to establish a regional credit transfer system and harmonize quality assurance mechanisms [4] among its member states. Comparable initiatives have sprung up over the past two decades in the Maghreb [5] and in South America [6], as well as in Central Asia, where five countries are presently pursuing the creation of a Central Asian Higher Education Area [7].

Another example of these regional integration trends is the attempted harmonization of education systems in the East African Community (EAC). In April 2017, the presidents of the six member states in the EAC pledged “to accomplish the … harmonization of higher education and training systems … to facilitate comparability, compatibility, and mutual recognition of higher education and training systems and the qualifications attained within the EAC … based on shared views on quality, criteria, standards, and learning outcomes, for promoting student and labor mobility [8] ….”

By design at least, the East African harmonization project closely follows the blueprint of the Bologna declaration. This article describes the harmonization reforms in East Africa and analyzes the genesis, planned structural changes, and future prospects of the EAC’s Common Higher Education Area (CHEA). The takeaway is that the EAC has put forward an ambitious integration agenda, but still faces significant hurdles in implementing these reforms in the near future.

The Genesis of the East African CHEA

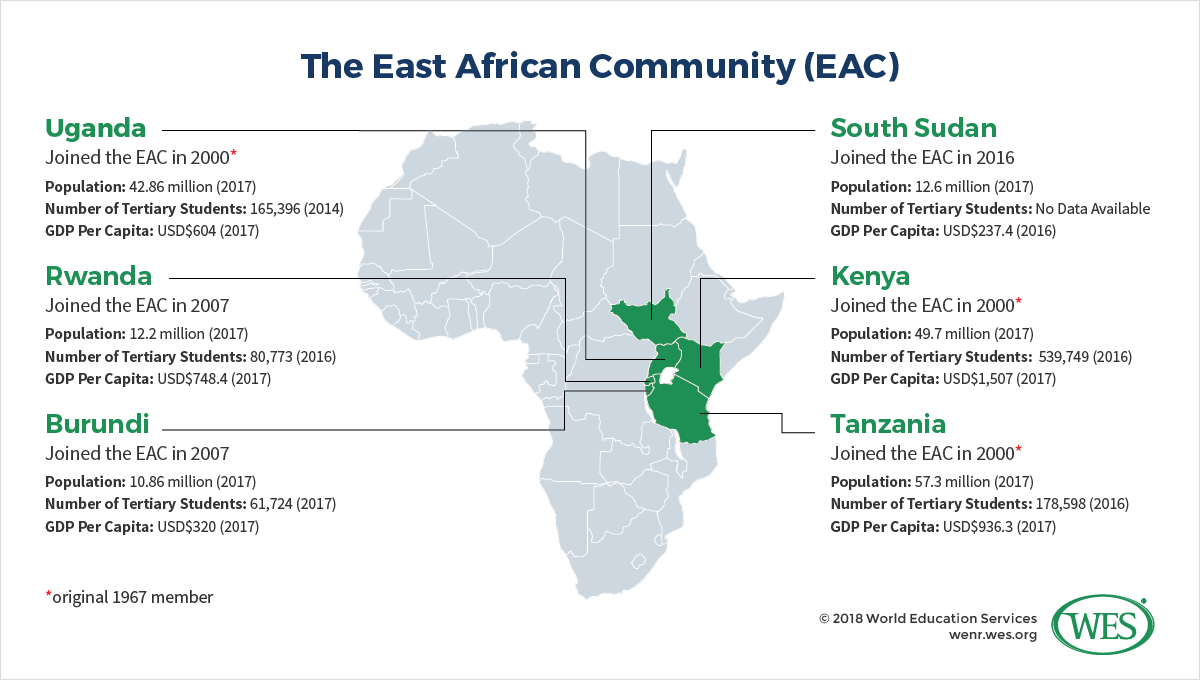

The EAC is a regional intergovernmental organization and economic community comprising more than 185 million people and over one million tertiary students combined.1 [9] It consists of Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, South Sudan, Tanzania, and Uganda. As in the case of the Bologna reforms, current efforts to harmonize education in East Africa are attempted against the backdrop of increased economic integration.

Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania2 [10] were part of the British colonial empire and economically already inter-connected because of colonial trading patterns and transportation links like railway lines. After independence, these three countries sought increased economic cooperation in areas like customs, labor migration, and taxation, and in 1967 formed the first iteration of the EAC to create a common market.

However, this first version collapsed in 1977 and was followed by a brief period of international conflict, including the Uganda–Tanzania War from 1978 to 1979. In 2000, the three countries restored the EAC and pushed ahead with renewed efforts to remove trade barriers and integrate their economies—a development that helped accelerate intra-regional trade by 96 percent between 2004 and 2009 alone [11]. Burundi and Rwanda joined the community in 2007, followed by South Sudan in 2016, which acceded to the EAC treaty just five years after becoming an independent state.

[12]

[12]

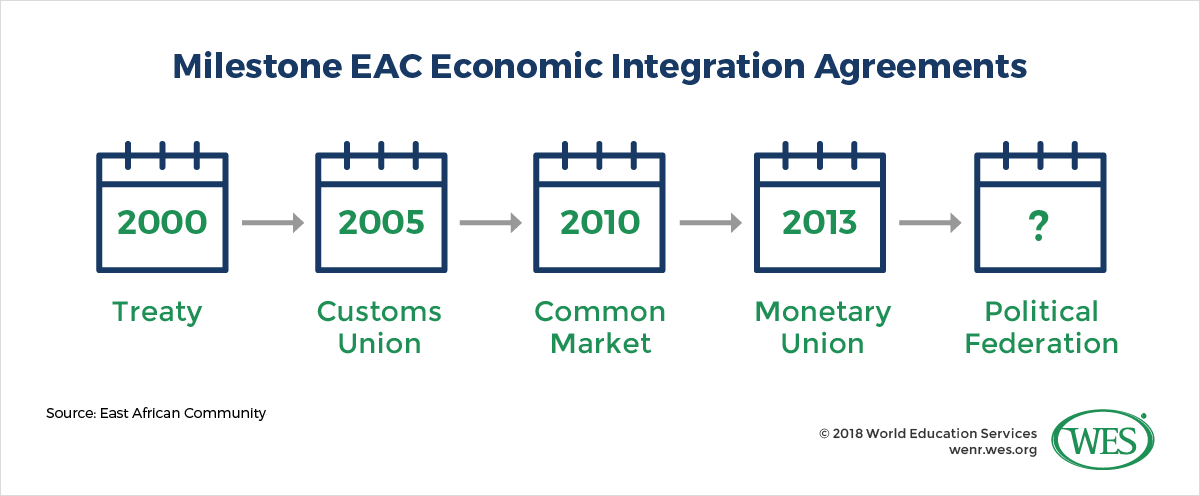

Efforts to deepen economic integration within the community were expedited in the 21st century. In 2005 the EAC countries formed a customs union—an agreement that in 2010 was extended to a full-fledged common market [13] to allow for the free movement of goods, services, labor, persons, and capital.

In 2013, the EAC member states then further committed to form a monetary union [14] and create a common currency within 10 years, at which point monetary policies are expected to be harmonized and regulated by a supranational EAC central bank. The ultimate goal of the current reforms is the establishment of a formal political confederation by 2021, although it remains highly uncertain if and when this ambitious objective can be achieved [15]. The EAC already has a joint, if fairly powerless, legislative organ in the East African Legislative Assembly [16].

Current Education Reforms

The implementation of most of the EAC’s harmonization efforts has been delegated to the Inter-University Council for East Africa (IUCEA), a coordinating and steering body headquartered in Kampala, Uganda’s capital. The IUCEA comprises 116 [18] members: universities and other degree-granting higher education institutions (HEIs), as well as dozens of associate member institutions.

As of now, council membership is voluntary and by application, although the IUCEA seeks to eventually admit all 300 universities presently operating in the EAC [18]. Institutions must be officially recognized in their home countries and have at least some internal quality assurance systems in place.

There is presently only one member university from South Sudan (the Rumbek University of Science and Technology). The country’s education system is nascent, and several of its HEIs have not yet been admitted.

A Regional Quality Assurance Framework

In the late 2000s, the IUCEA developed a detailed Handbook for Quality Assurance in Higher Education [19] and trained several senior university administrators (vice-chancellors, principals, executive officers, and others) in best quality assurance (QA) practices with the help of Germany’s Rectors’ Conference and the German Academic Exchange Service. The council subsequently created in 2012 a more comprehensive East African Higher Education Quality Assurance Network (EAQAN [20]).

EAQAN is tasked with fostering the establishment of QA units at universities, and strengthening QA systems within universities and national QA bodies. To achieve these objectives, EAQAN pursues the continual training of dedicated QA officers, and promotes knowledge and information exchange, regional QA forums, and the development of common standards and training materials [21].

It should be noted, however, that EAQAN does not have the authority to impose QA procedures, but relies on the voluntary cooperation of universities and national government bodies for the implementation of its quality standards. Deliberations to establish EAQAN as a more robust regional accreditation and oversight body faced resistance from the EAC member states [22]. As a result, there are presently no plans to set up external accreditation agencies beyond national QA authorities. More than 80 universities had joined the EAQAN network as of 2015 [21].

The East African Qualifications Framework for Higher Education

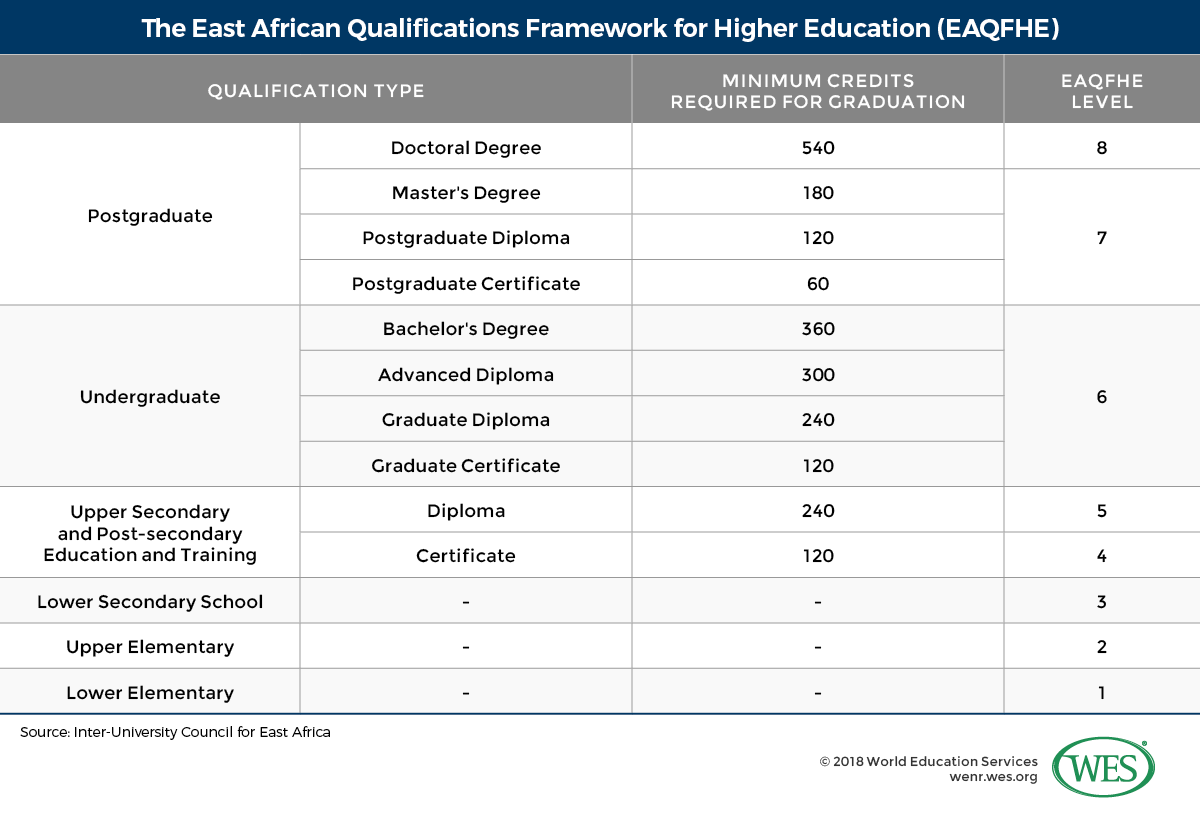

When the EAC states agreed to create a common market, they decided to strengthen economic integration with the establishment of a regional qualifications framework in order to “facilitate easy mobility of learners and labor” and enable the “mutual recognition of academic and professional qualifications across the region [18].” Years in the making and financially supported by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, the IUCEA in 2015 presented a comprehensive East African Qualifications Framework for Higher Education (EAQFHE)—a key tool for the harmonization of EAC education systems.

The EAQFHE codifies the length, structure, and learning outcomes of academic degree programs. Beyond that, it establishes a common credit system and specifies minimum credit requirements for established benchmark qualifications, akin to the ECTS (European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System) credit system of the Bologna reforms. While some of the current policy documents published by the IUCEA appear to be incomplete, the official EAQFHE guidelines [23] define one credit unit as 10 hours of notional learning time (including both contact hours and out-of- classroom study).

Called EACAT (East African Credit Accumulation and Transfer), this new credit system is intended to make academic qualifications more comparable and to facilitate the transfer of credits between programs, as well as ease the recognition of prior learning. One year of full-time study equals 120 EACAT credits, according to the IUCEA guidelines [18].

Other notable aspects of the qualifications framework include the definition of set admission requirements, progression pathways, assessment criteria, and specific learning outcomes for each of the eight qualification levels laid down in the EAQFHE. Beyond that, the guidelines call for the standardization of credential names and the creation of an “East African Graduation Statement.” Similar to the European Diploma Supplement, this document would be issued together with degree certificates and provide information on the qualification. The framework has not yet been implemented, but the governments of the EAC countries are expected to eventually align their national qualification frameworks with the EAQFHE.

International Student Mobility and Intra-regional Research Activities

It’s an official goal of the IUCEA to cultivate international student exchange and promote “inter-university academic activities in teaching, research, and community service for enhanced regional integration through academic mobility.”3 [9] By most accounts, economic integration and a growing focus on internationalization have already yielded robust gains in mobility between the EAC member states in recent years.

While reliable data are scarce and most mobile students from the region study overseas in destinations like Europe, the United States, or China, Uganda has become an increasingly important international education hub for East African students. According to ICEF Monitor, the country hosted 16,000 international students in 2016, most of them from neighboring Kenya [25].

This trend is mirrored in Kenya—the economic powerhouse of the EA and a magnet for intra-regional labor migrants. The country presently takes in a reported 4,000 to 5,000 international students annually [26], mostly from East Africa. One recent study found that more than 25 percent [27] of foreign students at four sampled Kenyan universities came from East African countries, including sizable numbers of graduate students from Tanzania and Rwanda. Even Rwanda now hosts more foreign students: Minor as the total count may be, the number of international degree-seeking African students in the small country more than doubled within the past five years, from 524 in 2012 to 1,391 in 2017 (UNESCO [28]).

One reason for this growing mobility is a significant expansion of intra-regional research cooperation, along with greater availability of scholarships [29] for graduate students in recent years. One example is the World Bank-funded ACE II project known as the Eastern and Southern Africa Higher Education Centers of Excellence Project (ACE II [30]), launched in 2016. The five-year project supports the formation of research and innovation hubs at universities and institutes in the ACE II participating countries: Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda (in the EAC), as well as Ethiopia, Malawi, Mozambique, and Zambia.

These centers are designed to function as regional incubators for technical innovation and specialized research on topics relevant to regional development, such as irrigation or electrical micro grids. In total, the ACE II project funds 24 centers where more than 3,500 graduate students conduct research, including at least 700 PhD students [31]. Rwanda alone has four of these centers, which are accessible to qualified students from all ACE II countries, including Burundi, which does not have any ACE centers.

Future Prospects: Still a Long Road to a Common Higher Education Area

Despite the EAC’s ambitious objectives and recent increases in intra-regional mobility, the challenges to creating a CHEA in East Africa remain formidable. The EAC is a group of highly heterogeneous and unevenly developed countries inundated by rapid population growth and severe capacity shortages in higher education. Not counting South Sudan, the number of tertiary students in the EAC has almost tripled over the past decade, overburdening education systems and exacerbating chronic funding crises. The number of tertiary students in Kenya, for example, literally exploded from 167,983 in 2009 to 539,749 in 2016 [28], while most of the country’s public universities are technically bankrupt [32].

This scarcity of resources complicates the implementation of large-scale reforms and means that bodies like EQAN have neither adequate staffing nor infrastructure. There’s consequently “still a lack of a critical mass of QA experts [21]” and effective steering mechanisms in the EAC.

There are also substantial structural barriers to overcome between the different countries’ systems. The length, curricula, credit, and assessment systems of academic degree programs vary substantially not only between Anglophone countries and countries with a Francophone legacy, but even between the UK-patterned systems themselves. While Kenya has a 12+4 system with four-year bachelor’s programs, Tanzania and Uganda have three-year bachelor’s programs and require entrants to higher education to complete a two-year advanced-level secondary program after 11 years of school (11+2+3). As a result, “public universities in Uganda require that … Kenyan candidates undergo Advanced Secondary (A-level) studies for 2 years while … private universities insist on a 6–9 months bridging course [33].” Burundi has a 13+4 system, while Rwanda and South Sudan have 12+4 systems, like Kenya.

As the Bologna reforms have illustrated, the restructuring and alignment of degree programs is far from insurmountable, notwithstanding opposition from universities and other stakeholders to transforming long-standing structures. That said, the implementation of such far-reaching reforms requires political will and a readiness to forgo certain national and institutional prerogatives. And therein lies perhaps the biggest challenge for the creation of a CHEA in East Africa: As of now, many integration and harmonization efforts in the EAC remain impeded by the nationalistic interests of countries that do not see eye to eye on a host of issues.

This is apparent in the economic sphere, where member countries are still reluctant to fully liberalize their labor markets and continue to impose barriers to protect local jobs from foreign competition despite multilateral agreements to the contrary [34]. The EAC customs union, which was meant to be in full effect by 2010, was in 2018 postponed indefinitely [35] because countries continue to unilaterally shield specific industries of national importance. It’s not easy to form an economic union between unevenly developed countries that lack strong regulatory institutions and effective revenue-sharing mechanisms.

Similar setbacks can likely be expected in the education sector, where integration is still embryonic. Unsurprisingly, perhaps, fiscal issues like the agreed-upon equal treatment of students from all member countries in terms of tuition fees face resistance from underfunded universities [36], more than half of which are not yet full members of the IUCEA. Some universities also fear that the increased transferability of qualifications will cause them to lose students to institutions in other countries [37]. At any rate, the costs associated with transforming degree structures and curricula are a considerable obstacle, while entrenched interests and the reluctance to cede sovereign rights and institutional autonomy will likely slow academic integration for some time to come.

In light of these realities, the present strategy of the IUECA is to promote awareness of the reforms and their benefits, and to prioritize the harmonization of graduate education [38], rather than push for the immediate standardization of education systems at all levels of tertiary education. As its executive director put it [39], “there is still a long way to go.”

The reforms are bound to progress in the years ahead, but it’s unrealistic to expect the East African CHEA to emerge swiftly, uniformly, or linearly. In this sense, analyzing the nascent East African CHEA is a bit like looking back at the Bologna reforms, which also evolved in a drawn-out process at varying speeds in various countries and institutions, if under what could arguably be considered more favorable structural conditions.

1. [40] Population as of 2017, as per the World Bank [41]. The number of tertiary students includes students in all types of programs, according to the latest available data provided by the UNESCO Institute of Statistics (UIS [28]). No data are available for South Sudan.

2. [42] Most of Tanzania (except for Zanzibar) was a German colony until the end of World War I but came under British control in 1919.

3. [40] Inter-University Council of East Africa: Academic Staff Mobility Policy Framework, Kampala, 2015. See:https://www.iucea.org/index.php?option=com_phocadownload&view=category&download=149:iucea-staff-mobility-policy-ips&id=21:opportunities&Itemid=613 [43]