Viktoria Jenkins, Senior Credential Analyst, WES, Makala Skinner, Research Associate, WES, and Stefan Trines, Research Editor, WENR

This education system profile describes recent trends in Dutch education and international student mobility and provides an overview of the structure of the education system of the Netherlands.

Introduction

The Netherlands is a relatively small Western European country with 17 million people living on a territory that measures merely a 10th of the U.S. state of California. This means that the Netherlands is the 22nd most densely populated country in the world [2], as well as the country with the highest population density in Europe.

A foreign trade and export-oriented nation for centuries, the Netherlands was at the forefront of European integration after World War II. Together with Belgium, France, Germany, Luxembourg, and Italy, the country in 1951 formed the European Coal and Steel Community – an embryonic predecessor of the European Economic Community and eventual European Union (EU), to which the Netherlands ascended as an original signatory.

The Netherlands was also one of the original 29 signatory countries of the 1999 Bologna Declaration and implemented reforms like the two-cycle degree structure, independent accreditation mechanisms, and the ECTS credit system rather quickly, compared to other European countries [4].

In the same vein, the Netherlands is presently pursuing a forceful internationalization strategy and seeks to attract growing numbers of international students and immigrants. The country considers internationalization vital for nurturing an outward-looking and interculturally competent citizenry and for strengthening the country’s status as a knowledge economy [5].

Beyond that, attracting foreign talent is seen as a necessary means to counter the aging of Dutch society and the concomitant risk of labor shortages [6]. While the Dutch population is still relatively young compared with those of other European countries like Italy, Greece, or Germany, about half of the Dutch population will be over the age of 50 by 2019 [7]. The country’s population over the age of 60, meanwhile, is expected to increase from 25 percent in 2017 to almost 34 percent by 2050 [8], while the overall population size is projected to remain flat [9].

In light of these trends, the Netherlands has in recent years intensified its international recruitment efforts. One recent example was the so-called “Make it in the Netherlands [10]” initiative, launched in 2014 as a collaborative effort by the Dutch government, companies, and universities to “retain talented international students for the Dutch job market” and “facilitate the transition from study to work for international students” with measures like language training, cultural immersion programs, and the streamlining of visa procedures.

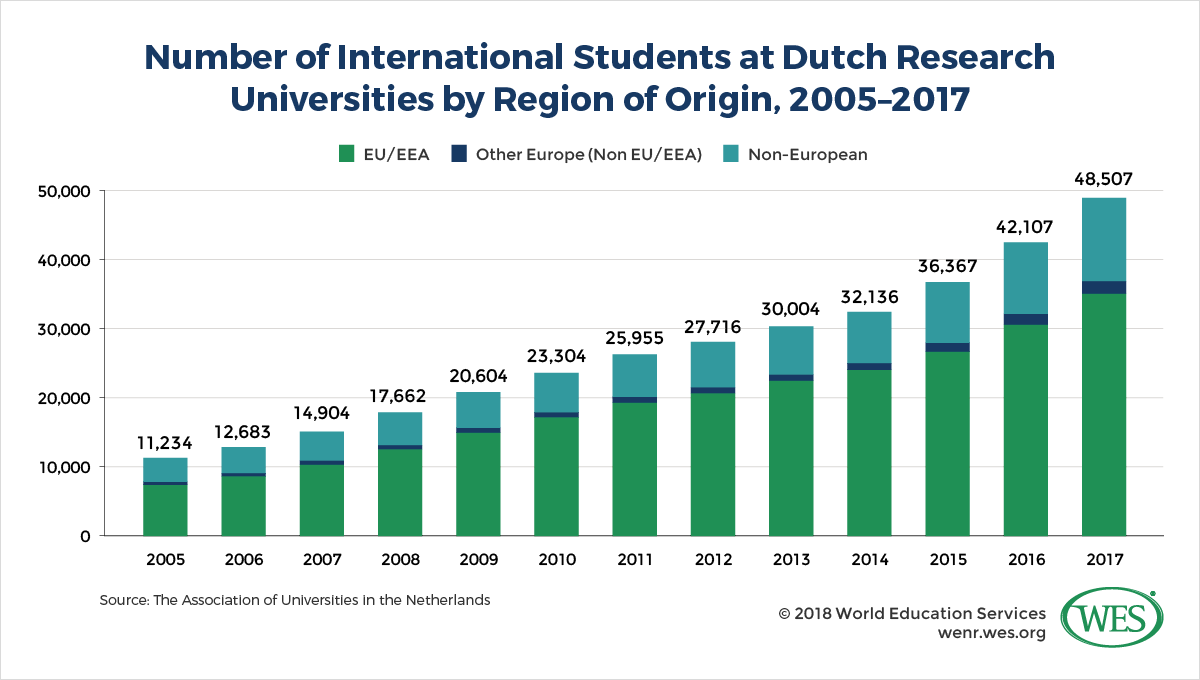

This openness to immigration and the availability of post-study work opportunities have helped fuel a drastic increase in international student inflows: The number of international students enrolled at Dutch research universities alone has risen by 332 percent over the past 12 years.

While student retention rates have fluctuated in recent years due to factors like an economic recession and high unemployment rates in the early 2010s, sizable numbers of international students – 22 percent [12] of 2012 graduates – stay in the Netherlands after graduation, helping to bridge skilled labor shortages in fields like health care. Stay rates are particularly high among graduates from technical universities, 40 percent of whom currently transition into long-term residency [12]. Notably, four out of nine Ph.D. students who were registered for employment in the Netherlands in 2015 were foreign nationals [13].

However, the extent and speed of internationalization have recently generated mounting resistance in the Netherlands. While the current government seeks to expand international student enrollments even further, there’s now growing criticism from opposition parties, academics, students, and the media of the sometimes negative consequences of internationalization, such as deteriorating student-to-teacher ratios [14], severe shortages of student housing, and rising rents because of the rapidly growing influx of international students [15].

Other concerns relate to fears that Dutch students will be “crowded out [16]” of universities since they have to increasingly compete with omnipresent international students. In 2018, international students constituted a majority of the student body in 210 university programs and made up not less than 75 percent of all students in 70 of these programs [17]. International demand in disciplines like computer science or engineering has become so overpowering that the Delft University of Technology recently had to enact an admissions freeze for non-EU nationals [17].

Most controversial, however, is the rising use of English as the medium of instruction at universities – a trend that is driven by the fact that English-taught programs are a major draw for international students. The Netherlands now has the largest number of English-taught degree programs in all of Europe – 12 of the country’s top universities offered 104 bachelor and 930 master programs in English as of 2015, according to Studyportals [18]. Statistics of the Dutch Organization for Internationalization in Education (Nuffic) show that 23 percent of all bachelor’s programs and 74 percent [13] of master’s programs were exclusively taught in English in 2018.

This rapid upsurge in English-taught programs has caused growing unease about the marginalization of the Dutch language in education and the “de-wording” and simplification of academic discourse. Student organizations are alarmed that professors’ English proficiency and the proficiency of Dutch students themselves is not high enough to maintain the same level of quality in courses taught in Dutch [19] – despite the fact that the Netherlands is viewed as having the highest level of English proficiency among all non-English-speaking EU countries after Sweden [20].

Reflective of the recent controversies, the Dutch newspaper De Telegraaf in 2018 headlined an article [21] with the message “stop the English madness,” while the organization Better Education Netherlands went so far as to sue two universities for offering too many English-taught programs. The organization argued that the universities chose English as the language of instruction for purely financial reasons rather than for academic benefit, but ultimately lost the case [22].

Like several other European countries, the Netherlands is also experiencing a growing and increasingly vocal pushback [23] against immigration in general, as well as mounting opposition to European integration. This is reflected, for example, in the rise of Geert Wilders’ anti-immigrant, anti-EU Freedom Party (Partij voor de Vrijheid – PVV), which became the second-largest party in the Dutch parliament after winning 13 percent of the vote in the 2017 general elections. While the Netherlands remains an open and immigration-friendly society at large – a recent poll [24] showed that 77 percent of Dutch people supported taking in refugees, for instance – the rising ethno-nationalist and xenophobic undercurrents [25] in Dutch society represent a significant challenge for a country that is widely viewed as a tolerant and progressive nation.

Inbound Student Mobility

The extent to which the Netherlands has transformed into an in-high-demand study destination over the past two decades is remarkable. Between 1999 – the year the Bologna Declaration was signed – and 2016, the number of international degree-seeking students in the country grew by fully 560 percent, from 13,619 to 89,920 students, according to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS [26]).

While that’s a relatively minor number compared with the 244,575 international students the UIS reported for neighboring Germany in the same year, it’s factually a very high count, given the Netherlands’ small size. The share of international students among all tertiary enrollments in the Netherlands is 10.7 percent, compared with 8 percent in Germany and only 5 percent in the U.S., which is the world’s leading destination for mobile students (UIS [26]).

The number of inbound international students is even higher when taking into account individuals that pursue short-term studies (Erasmus exchanges, vocational traineeships, and so on). According to Nuffic statistics [13], the total number of international students of all types reached a record high of 122,000 in 2018 – an increase of 10,000 over the previous year.

Aside from the availability of a large variety of English-taught programs, the Netherlands is attractive to mobile students because of its comparatively low tuition costs, which start at €2,060 (USD$2,324) annually for students from the European Economic Area; and range from €8,000 to €20,000 (USD$9,027 to $USD22,568) for a master’s program for nationals from other, mostly non-European countries [27].

Another draw for international students is the country’s global reputation for high-quality education and the robust standing of its universities in international university rankings. Top-ranked research universities like the University of Amsterdam and the renowned Delft University of Technology are among the top five recipient institutions of international students, although it should be noted that the largest numbers of international students are enrolled at the lesser-ranked Maastricht University – a globally active institution that offers transnational programs and an international student population that makes up 58 percent [13] of its total student body.

Dutch Universities in International University Rankings

International university rankings are a questionable proxy for institutional quality and are often criticized for their methodology. But warranted or not, these rankings influence the choices of mobile students and, as it stands, Dutch universities are well represented in prominent international rankings, despite the Netherlands being a comparatively small country. For example, seven Dutch universities are included among the top 100 in the 2019 Times Higher Education World University Rankings [28], compared with eight German universities. They are the Delft University of Technology (ranked 58), Wageningen University (59), the University of Amsterdam (62), Leiden University (68), the Erasmus University Rotterdam (70), Utrecht University (74), and the University of Groningen (79). The latest QS ranking [29] includes the Delft University of Technology (52), the University of Amsterdam (57), and the Eindhoven University of Technology (99) among its top-rated institutions, while the 2018 Shanghai Ranking [30] features Utrecht University, the University of Groningen, Leiden University, and the Erasmus University Rotterdam among the top 100.

About 69 percent of international degree-seeking students in the Netherlands are enrolled in bachelor’s programs, a majority of them at universities of applied sciences. That said, enrollments in master’s programs are presently surging and a primary driver of growth with 14,496 new international students entering a master’s program in the 2017/18 academic year [13] alone.

The number of international Ph.D. students is still relatively small with 4,942 students in 2016, but has spiked by 75 percent over the past decade [13], so that Nuffic now projects that 50 percent of all doctoral students in the Netherlands will be international students in the near future.

The most popular fields of study among international students in the Netherlands are economics and business, engineering, humanities, and social sciences, although this varies between students enrolled in research universities and those studying at universities of applied sciences. Psychology, in particular, is a highly popular subject among international students.

Countries of Origin

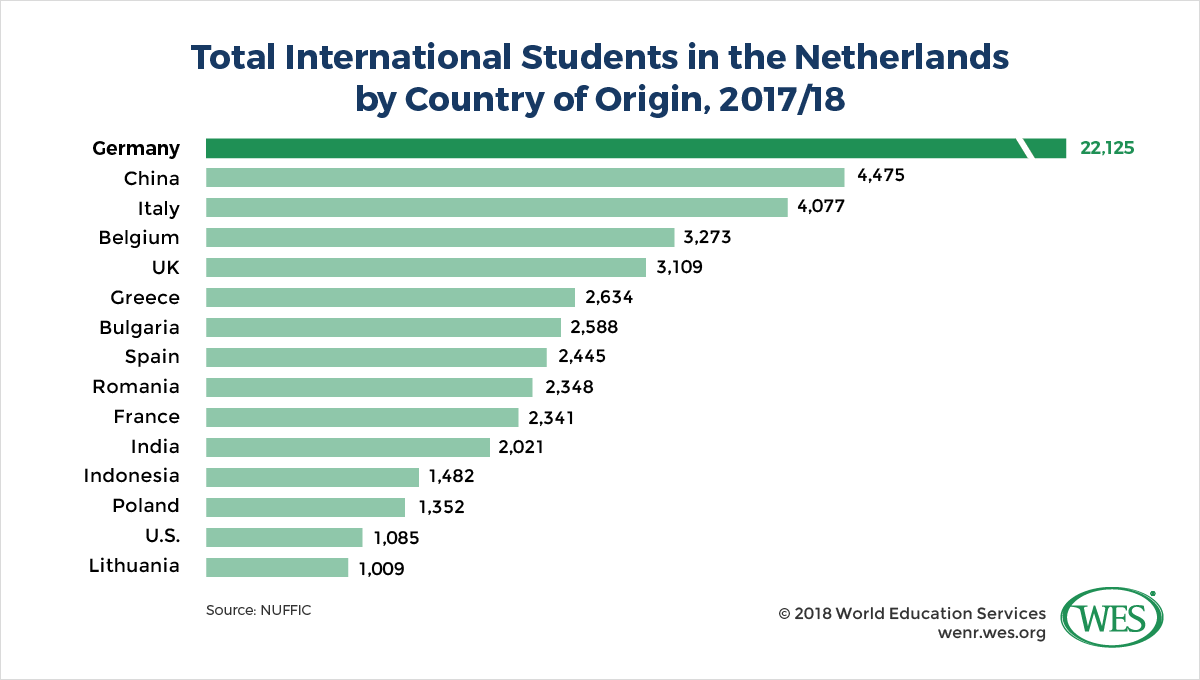

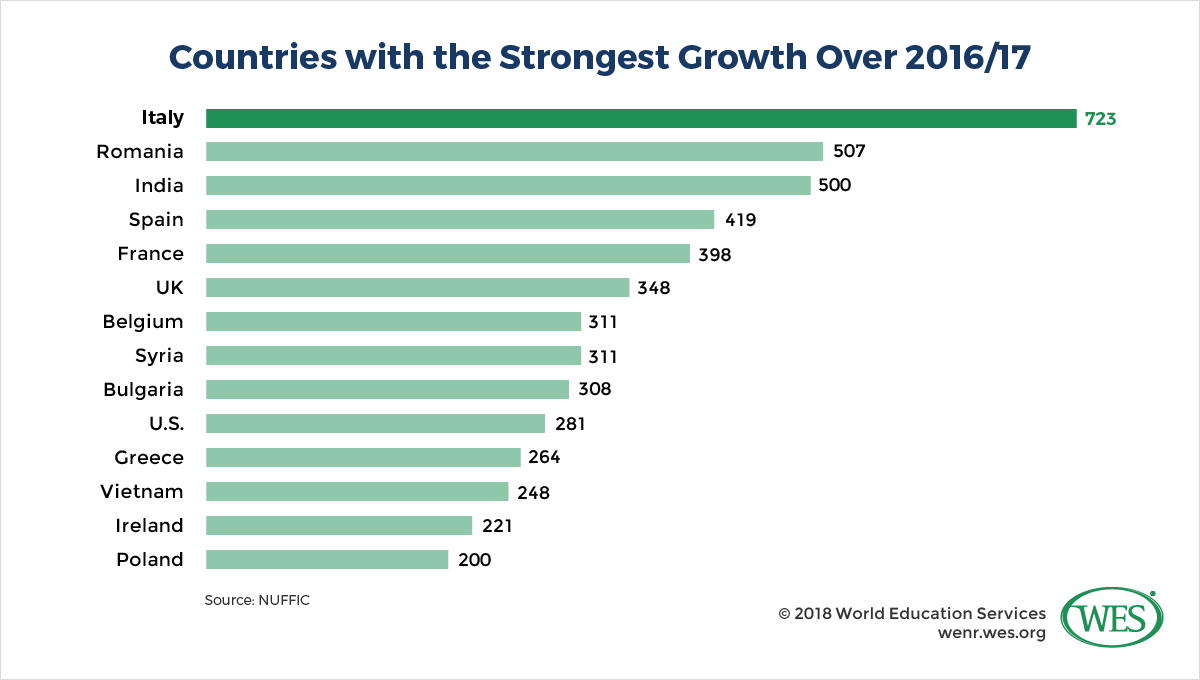

While international students in the Netherlands come from 162 different nations, the overwhelming majority are from other EU countries, particularly neighboring Germany, which has been the largest sending country for more than a decade. Germans presently make up almost 25 percent of all international students (22,125 students [13]) in the Netherlands, followed, distantly, by China with 4,475 students, and various EU countries, including Italy, Belgium, the United Kingdom, and Greece. However, German enrollments have leveled off since 2011, while Chinese enrollments are now largely stagnant. The three most dynamic growth markets for the Netherlands are currently Romania, India, and especially Italy, which is expected to soon surpass China as the second-largest sending country.

It’s worth noting that the Dutch government has set up dedicated Netherlands Education Support Offices (NESO) to market the Netherlands as a study destination in 11 strategically important sending countries that – as Dutch authorities see it – have “expanding demographics, economics, and higher education systems [33].” Recruitment efforts in these countries—Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Russia, South Africa, South Korea, Thailand, Turkey, and Vietnam—appear to have paid off, notably in places like India, Indonesia, and Vietnam. Overall enrollments from countries that have NESO offices have doubled since 2006 and now account for more than 13 percent of international degree enrollments in the Netherlands [13].

Outbound Student Mobility

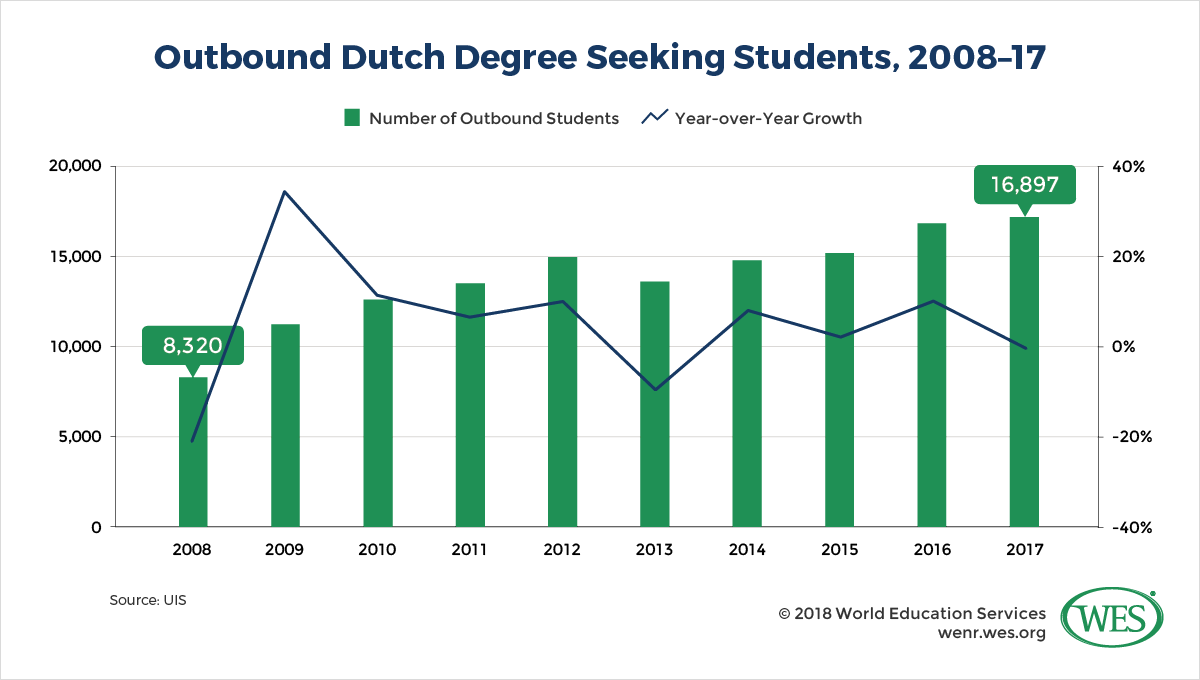

Compared with the skyrocketing inbound student flows, the total number of outbound students from the Netherlands is small, but not insignificant in relative terms and growing strongly in recent years. Between 2008 and 2017, the number of international degree-seeking students from the country doubled from 8,320 to 16,897 [26], which means that 2 percent of Dutch tertiary students are currently enrolled abroad. While that’s just about half of Germany’s percentage, it’s twice as high as that of the major sending country India, which had an outbound mobility ratio of only 0.9 percent in 2016 (UIS [26]).

In addition, there are a number of Dutch nationals studying abroad on a short-term basis—a form of mobility commonly called credit mobility. In 2015/16, 2,127 Dutch students [35] temporarily enrolled in other EU countries in Erasmus-sponsored study abroad programs or vocational internships. More than half of these students were in sunny Spain, but the U.K., Germany, Belgium, and Malta also drew significant numbers of students.

Dutch degree-seeking students, on the other hand, are predominantly clustered in just three destination countries – in 2017, 58 percent of these students were enrolled in neighboring Belgium (26 percent), the U.K. (20 percent), and the U.S. (12 percent [26]). Other popular destination countries included France, Denmark, and Sweden.

Trends in the U.S. and Canada

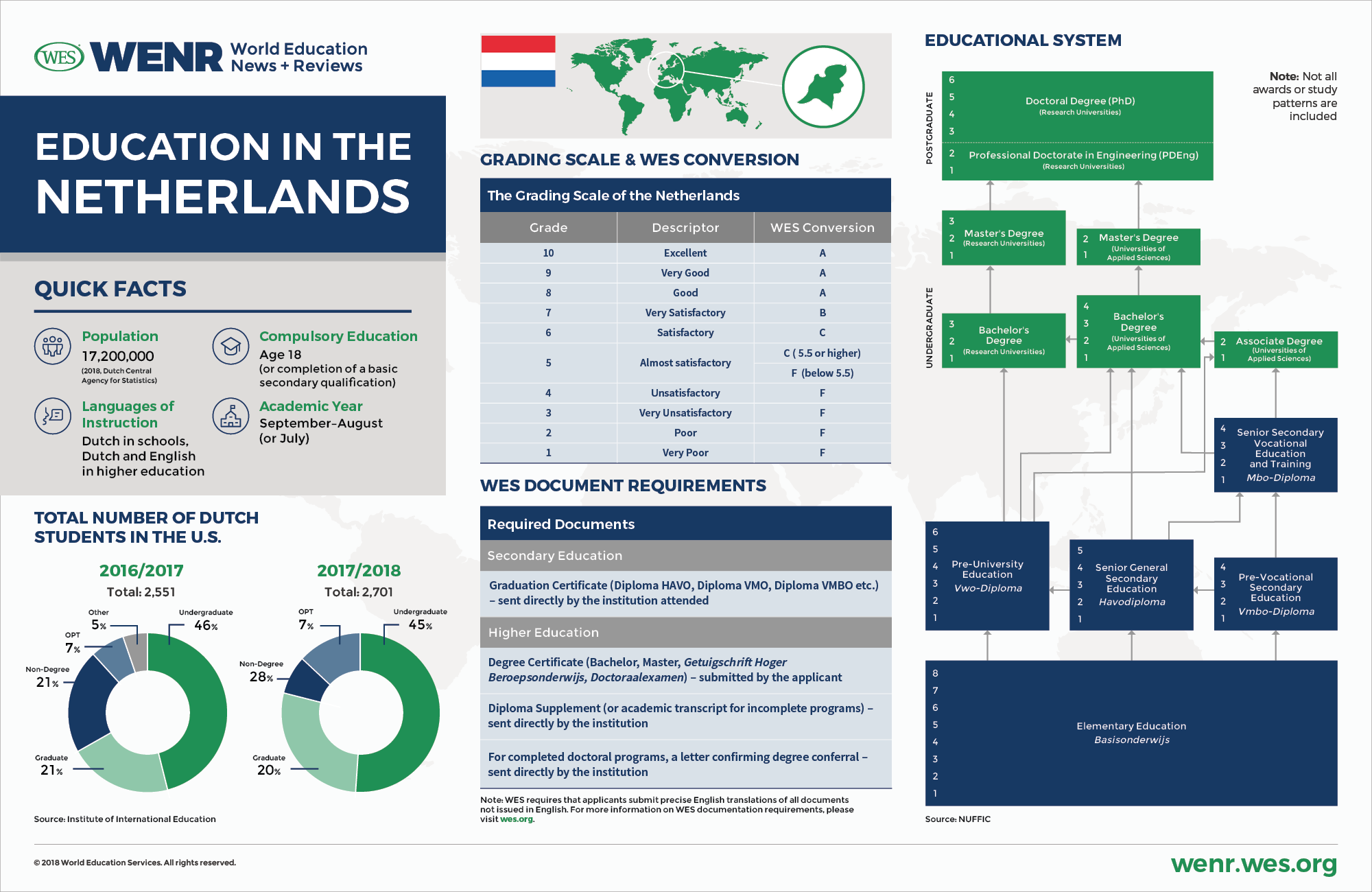

Parallel to the general increase in outbound mobility from the Netherlands, Dutch enrollments in the U.S. have been on an upward trajectory in recent years, according to the Institute of International Education’s Open Doors data [37]. Compared with just 1,680 students in 2007/08, there were 2,701 Dutch students in the U.S. in 2017/18 – a 5.9 percent increase from the previous year. Nearly half of these students – 45 percent – were enrolled at the undergraduate level, while only 20 percent pursued graduate studies. Seven percent of Dutch students were in OPT, and 28 percent were enrolled in non-degree programs.

The number of Dutch students in Canada has also increased but on a much smaller scale. According to Canadian government statistics [38], Dutch enrollments increased from 360 in 2007 to a record high of 515 in 2017, after numbers had slightly dipped in the early 2010s, possibly due to the economic recession in the Netherlands. According to UIS data [26], Canada is presently the 10th most popular destination country of international degree-seeking students from the Netherlands.

In Brief: The Education System of the Netherlands

The evolution of the modern Dutch education system traces back to the 1801 Elementary Education Act, the first formal education law in the country that enshrined the responsibility of the government to provide free elementary education to all children unable to afford education at private religious schools [39]. What is remarkable about the Dutch system compared with other European countries is that the state did not subsequently monopolize and secularize school education: Parochial schools (mostly Roman Catholic and Protestant, but also Jewish, Hindu and Muslim) are ubiquitous and even dominant today. These private religiously affiliated providers are also entitled to receive the same level of government funding as public institutions.

The constitution of the Netherlands guarantees what is almost unthinkable in most European countries: nearly universal “freedom of education [40],” which means that anyone can open and run private schools [41], as long as the schools comply with certain benchmark requirements related to the minimum numbers of pupils, safety regulations, compulsory hours of classroom instruction, and other criteria. Schools are free to design their own curricula and learning methods, and are allowed to “require its teaching staff and pupils to subscribe to the beliefs of their denomination or ideology [42].”

While this policy results in a highly diverse school system and far greater disparities between schools in terms of quality and learning outcomes than in other countries [43], the Dutch education system is generally considered to be of top quality. Dutch pupils consistently perform above average in the OECD PISA study [44], and the OECD noted in 2016 [45] that the “Dutch school system is one of the best in the OECD … equitable, with a very low proportion of poor performers. Basic skills are very good on average, while the system … is supplemented by a strong vocational education and training system with good labor market outcomes.”

In higher education, the Netherlands is ranked seventh among 50 countries in the 2018 Ranking of National Higher Education Systems by the Universitas 21 network of research universities [46]. The country is also ranked second behind Switzerland in the Global Innovation Index [47], a study that measures research performance and potential for innovation. As mentioned before, Dutch universities are well represented in the most prominent global university rankings.

Administration of the Education System

A parliamentary democracy since 1848, the Kingdom of the Netherlands is simultaneously a constitutional monarchy that consists not only of the European Netherlands, but also the Caribbean island nations of Aruba, Curacao, and St. Maarten. These former Dutch colonies are now autonomous countries, not part of the EU, that administer their own education systems. They are consequently not covered in this article (for more information see the Nuffic publication [48] on the Education System of Curacao, St. Maarten, and the BES islands).

The Netherlands comprises 12 provinces, each of which has its own unique cultural and linguistic characteristics. However, education is centrally administered by the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science (MOE) in The Hague, which sets the overall regulatory framework for education and provides funding for all levels of education.

That said, the Dutch system is decentralized with academic institutions at all levels of education having an extraordinarily high degree of autonomy in various matters, such as curriculum development or the hiring of teachers. Schools at the lower secondary level, for instance, in 2011 “made 86 percent of key decisions (compared to an OECD average of 41 percent), with the remaining 14 percent made by central government. Schools made 100 percent of the decisions regarding the organization of instruction, personnel management and resource management.”

While private schools are free to design their own curricula and teaching methods, it should be noted that the MOE ensures consistency by prescribing mandatory school subjects and defined learning outcomes for these subjects. The acquisition of required knowledge in mandatory subjects is tested in an attainment test [49] at the end of elementary education, as well as in nationwide external examinations at the end of secondary education. Both private and public schools are also evaluated by the Inspectorate of Education [50], a government body that monitors quality standards and prepares annual State of Education reports for the MOE. There have been discussions in recent years to introduce national exit examinations in higher education as well, but universities presently continue to conduct their own graduation exams.

The vast majority of Dutch elementary and secondary schools – 66 percent – were privately run in 2009 – a fact reflected by two-thirds of 15-year-olds being enrolled in private schools, while only one-third attended public schools [51]. Most private schools are parochial schools and almost all of them receive public funding [51]. While this system works well in general, there have been growing concerns in recent years that the extreme diversity of schools is facilitating the segregation of children along ethnic and socioeconomic lines, particularly in the cities [52].

Compulsory School Age, Academic Calendar, and Language of Instruction

Compulsory education starts at the age of five, although nearly all children enter elementary school at the early age of four. While compulsory school attendance (leerplicht) formally ends at the age of 16 [53], compulsory education has since 2007 been extended to the age of 18, since all youngsters under 18 are now mandated to stay in school until they obtain a “basic qualification,” that is, an upper-secondary school leaving qualification, or a formal vocational qualification (kwalificatieplicht). This means that the length of compulsory education in the Netherlands is now longer than in most OECD countries. There are considerations to even further extend the kwalificatieplicht until age 21.

The academic year runs from September to August (July in some regions) at both schools and universities, which typically divide the academic year into two semesters. The language of instruction in schools is Dutch, although some schools in the province of Friesland may also use Frisian – a local minority language that is recognized as a second national language in the Netherlands – as a language of instruction alongside Dutch [54]. In higher education, the languages of instruction are Dutch and, increasingly, English.

Elementary Education

Elementary education (basisonderwijs) is provided free of charge at both public and private schools and lasts eight years (groep 1 to 8). The compulsory core subjects that must be taught to all children are Dutch, English (introduced in grade seven), arithmetic and mathematics, creative expression (music and arts), physical education, and social and environmental studies (biology, geography, history, political studies, citizenship, road safety), with Frisian being a mandatory subject in Friesland [55] as well. All schools are also required to teach lessons on sexuality and sexual diversity. Schools may teach additional subjects beyond the mandatory core subjects. While public schools do not provide religious education, religion is taught in almost all private schools [55].

In the last year of elementary school, pupils sit for an external “central exam” in mandatory core subjects, administered by the Central Institute for Test Development (CITO [56]). Upon graduation, all elementary school leavers also receive a report “describing their attainment level and potential [57]” based on school assessments. In addition to test scores, teacher recommendations play a central role in the streaming of children into different tracks at the secondary level.

Secondary Education

Secondary education is offered free of charge at both public and private schools for all students under the age of 18. The secondary school system in the Netherlands is complex and perhaps one of the most diversified systems worldwide. At the end of elementary education, parents must decide whether to enroll their children in academic or vocational secondary school tracks based on test results and non-compulsory school recommendations. That said, transfers between the different tracks are still possible at later stages, at least to some extent. Students can also choose to upgrade to a second, usually higher-level secondary qualification after graduation – a pathway referred to as “stacking [58].”

There are two pathways in the academic track: Senior general secondary education (hoger algemeen voortgezet onderwijs – HAVO) and university-preparatory secondary education (voorbereidend wetenschappelljk onderwijs – VWO).

Alternatively, students can enroll in pre-vocational secondary education programs (voorbereidend middelbaar beroepsonderwijs – VMBO), which are shorter lower-secondary programs intended to prepare students for further vocational training. To make matters more complex, VMBO programs are offered in different forms, including theoretically oriented programs, as well as predominantly vocationally oriented programs, and combinations thereof. Finally, there are practical training programs (praktijkonderwijs, PRO) available for students whose academic abilities are most suited for learning a trade, rather than pursuing further school education. These applied programs last for four years and prepare students for direct entry into the labor market. We will briefly describe the structure of the most common programs below.

Overall, vocational tracks are most popular among Dutch parents and students. In 2017, 55.6 percent [59] of secondary students graduated with a pre-vocational qualification, while 25.6 percent and 18.8 percent graduated with a HAVO and VWO qualification, respectively. Pathway choices tend to be affected by socioeconomic status: As the MOE noted in 2018, the “majority of pupils on vocational tracks have less well-educated parents and, in the cities in particular, most have a migrant background. The pre-university VWO stream, by contrast, is dominated by pupils with better-educated parents and, in the cities, a non-migrant background [59].”

Senior General Secondary Education (HAVO) and University-Preparatory Education (VWO)

HAVO and VWO programs are designed to prepare students for higher professional education (Hoger beroepsonderwijs – HBO) and university education. While HAVO programs are five years in length and give access to HBO programs at universities of applied sciences, VWO programs are six years in length and give access to research universities. Schools make individual admissions decisions based on test scores and school recommendations, although a small number of schools may require additional entrance examinations [60].

Both programs include a general three-year foundation phase and a specialization phase, which lasts two years in the case of HAVO programs, and three years in VWO programs. The available specialization profiles (profielen) in the second phase are science and technology, science and health, economics and society, and culture and society, with each of these profiles having different subject combinations. HAVO students can transfer into VWO programs (and vice versa) after the foundation phase, or continue to earn a VWO diploma after completing a HAVO program (stacking).

In addition to specialization subjects, schools are required to teach a general education curriculum during the specialization phase that covers Dutch, English, culture and arts, social studies, physical education, and – in the case of VWO programs – mathematics and a second foreign language. Both programs conclude with a final school-based examination, as well as with an external nationwide examination (central exam), conducted in May each year, that usually covers seven (HAVO) or eight mandatory subjects (VWO) [60]. The formula for calculating the passing score for graduation is complicated, but requires, at minimum, an average central exam score of 5.5 or higher out of 10, in addition to minimum grades of 6 in almost all subjects in the school examinations (for more information, see here [61] and here [62]). Students who fail the central exam have the chance to retake it two times [63]. The final qualifications awarded are called Diploma-HAVO or Diploma –VWO.

Pre-Vocational Secondary Education (VMBO)

VMBO programs are shorter than academic programs. Students typically complete them at the age of 16. They last four years, divided into a two-year foundation phase and a two-year specialization phase. These programs are designed to prepare students for upper-secondary vocational training programs (middelbaar beroepsonderwijs –MBO), which are classified into four different levels, depending on the type of qualification and the level of complexity (MBO 1 to 4, discussed below).

There are four types of pre-vocational VMBO pathways that provide access to different levels of MBO programs. While all programs have the same general education curriculum in the foundation phase, the basic level pre-vocational program (basisberoepsgerichte leerweg – VMBO-BL) has a strong focus on industry-specific practical training in the specialization phase, and only provides access to MBO programs at levels 1 and 2. A second variation of this practice-oriented program is the more advanced middle-management vocational program (kaderberoepsgerichte leerweg – VMBO-KL), which includes theoretical instruction at a higher level [64], while still being an applied program. VMBO-KL graduates are eligible for admission into MBO programs at levels 3 and 4.

In addition, there is a more general and theoretical program called theoretische leerweg – VMBO-TL, which provides education at a more abstract level. An alternative to the VMBO-TL track is a mixed program called gemengde leerweg – VMBO-GL, which combines a small vocational training component with higher-level theoretical instruction. VMBO-TL and VMBO-GL graduates have access to MBO level 3 and 4 programs, and beyond that can transition into the fourth year of academic HAVO programs.

In the theoretical VMBO-TL track, there are four broad areas of possible specializations (business, agriculture, care and health, and engineering and technology), whereas students in all other programs can choose from 10 vocational specializations, including construction, transportation, media, design and information technology, maritime technology, and others [64]. At the end of the program students in all tracks sit for final school examinations, which may include a practical project in some cases, and external national examinations (central exam) in five or six subjects. The vast majority of VMBO graduates continue their education in MBO programs, although 15 percent of VMBO-TL and VMBO-GL graduates transitioned into HAVO programs in the 2015/16 academic year [59].

Upper-Secondary Vocational Education (MBO)

The Netherlands has a sophisticated, diverse, and internationally well-respected vocational education and training (VET) system. Financed generously by the government, which provides about 80 percent [65] of its total funding, the system helps to reduce the country’s youth unemployment rate, which was the eighth lowest in the OECD in 2017 at 8.8 percent [66]. Upper-secondary VET is highly popular among Dutch students – fully 68 percent [67] of upper-secondary students enrolled in VET programs in 2016, compared with an average of 44 percent in the OECD.

Upper-secondary VET is provided free of charge to students under the age of 18, but students older than 18 have to pay modest fees, which ranged from €232 (USD$263) annually for part-time studies to €1,118 (USD$1270) for full-time programs in 2015, depending on the type of program [68]. VET is provided by a variety of institutions, including public regional training centers (regionale opleidingscentrum – ROC) and agricultural training centers (agrarische opleidingscentrum – AOC), as well as by numerous smaller private schools [65].

Institutions provide education in accordance with governmental regulations (qualification files [69]) that define mandatory learning content, specific learning outcomes, and the level of MBO training for particular occupations. MBO diplomas are formally recognized vocational qualifications in the Netherlands and issued for more than 700 occupations, according to the MOE [70]. To name just a few examples, MBO programs exist for air conditioning mechanics, animal care workers, accounting assistants, bakers, bio-medical analysts, environmental inspectors, legal secretaries, nurses, print media technicians, shipbuilders, spatial design practitioners, telecommunications engineers, or video editors [71].

There are two types of programs, delineated by the amount of practical training required. In school-based programs (beroepsobleidende leerweg – BOL), students typically spend four days a week in school, augmented by one day of in-company training, although the practical training component can range anywhere between 20 percent and 60 percent [70], depending on the specific type of program.

In work-based apprenticeship programs (beroepsbegeleidende leerweg – BBL), on the other hand, practical training makes up more than 60 percent of the curriculum, which means that students usually spend four days a week at a workplace, while attending school one day a week. These types of programs require that students have a work contract with a government-accredited company, which pays students a modest salary, the minimum amount of which is set by the government. School-based programs are most common: In 2014, almost three-quarters of MBO students were enrolled in school-based BOL programs [72].

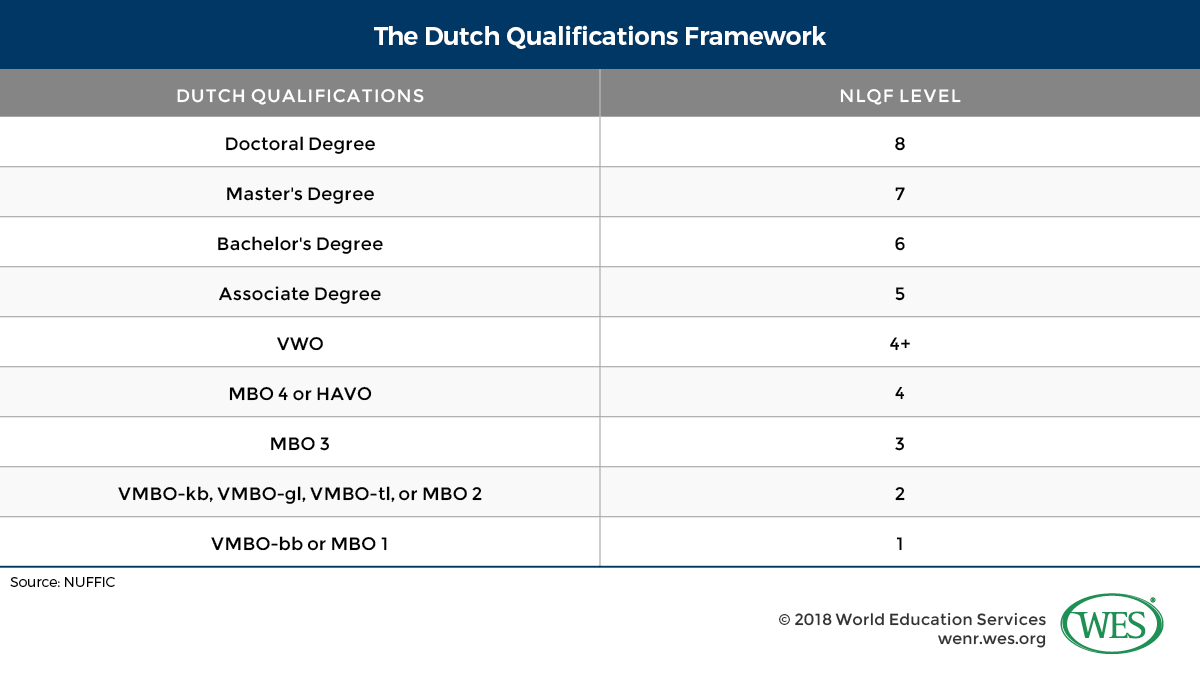

In addition to providing theoretical instruction in vocational subjects and practical training, MBO programs include a general education component. Graduation is mostly based on assessments by schools and employers, but all students must also sit for an external national examination in Dutch, English, and mathematics [73]. In terms of level, MBO programs are grouped into the following four categories (For a comparison of how these levels correspond to other secondary qualifications, see also the Dutch Qualifications Framework below.):

- MBO 1: Entry-level programs (entreeopleiding) that last up to one year and are open to all learners, including those who have not obtained a lower-secondary exit qualification. They are practical, labor-oriented programs primarily designed to prepare students for MBO 2 programs, but do not provide a formal qualification for entry into the labor market.

- MBO 2: Basic vocational programs (basisberoepsopleiding) that are one or two years in length and require either a VMBO or an MBO level 1 qualification for entry, although students in academic tracks can also enter after completion of the three-year foundation phase. MBO 2 programs prepare students for hands-on trades such as welding or hairdressing.

- MBO 3: Classified as “professional education” (vakopleiding), these programs last two to three years and provide more advanced and comprehensive training. MBO 3 programs can only be entered on the basis of a VMBO diploma or completion of the first three years of HAVO or VWO programs. MBO Level 1 or 2 diplomas do not qualify for entry.

- MBO 4: Classified as middle-management programs (middenkaderopleiding), MBO 4 programs have the same access requirements as MBO 3 programs and are three or four years in length, although reforms are underway to cap all MBO at three years [74]. MBO 4 programs deliver the highest level of education and training and provide access to higher education programs at universities of applied sciences. There is also a higher level MBO 4 specialist training program (specialistenopleiding) that takes an additional year of study after the initial MBO 4. In 2015/2016, more than 40 percent [59] of all MBO students completed a level 4 qualification with more than a third of these students transitioning into higher education.

Higher Education

As in the secondary school system, the Dutch higher education system has a binary structure that is delineated into academic or research-oriented education (wetenschappelijk onderwijs) offered by universities, and more applied higher professional education (hoger beroepsonderwijs- HBO) offered by universities of applied sciences (hogescholen).

Unlike in the school system, privately owned institutions don’t play a dominant role in Dutch higher education. There are only a few private institutions that enrolled about 14 percent of the total student population in 2016 (UIS [26]).

The total number of Dutch tertiary students in all types of programs has increased significantly over the past decade, from 590,121 in 2007 to 836,946 in 2016, according to UNESCO [26]. The tertiary gross enrollment ratio surged from 48 percent in 1998 to 80.5 percent in 2015 [76], but has since begun to level off. Dropout rates are high – three-quarters [77] of students at research universities left without earning a diploma as of 2016. The majority of students are enrolled in HBO programs – per the Dutch Central Agency for Statistics, 452,690 students [78] attended a hogescholen in the 2017/18 academic year, compared with 280,114 students at universities.

Types of Higher Education Institutions

In terms of funding mechanisms, there are 17 [79] government-funded research universities, which include four religiously affiliated universities that have special status, and 37 universities of applied sciences. There’s also the publicly funded Open University of the Netherlands [80], an open-access distance education provider that doesn’t have formal admissions requirements. It offers bachelor’s and master’s programs to about 14,000 students. Other public institutions include the Royal Academy of Arts [81] or the Netherlands Defense Academy, as well as eight University Medical Centers, which were created as a merger of medical university faculties and teaching hospitals [82].

Aside from publicly funded institutions, there are a number of “approved” private institutions – including the Nyenrode Business University (NBU) and private universities of applied sciences – that do not receive government funding but are authorized to award Dutch degrees. In contrast to public institutions, these institutions are free to charge tuition fees beyond the limits set by the government – NBU, for example, currently charges a hefty €39,500 (USD$44,862) for its MBA program [83].

In addition, there are a number of smaller, private for-profit schools and international institutions that operate outside of the Dutch system. That said, some of these institutions, such as the U.S.-based Webster University Leiden, have obtained accreditation of their degree programs by the Accreditation Organization of the Netherlands and Flanders, the accrediting body of the Netherlands (see below).

Research Universities

Most research universities – typically referred to simply as universiteit – are larger multi-disciplinary institutions that focus on academic education and scientific research and are the only institutions legally authorized to award doctoral degrees. Notably, a number of universities incorporate university colleges, which are patterned after the model of U.S. liberal arts colleges and offer English-taught bachelor programs with a multidisciplinary and holistic focus [84].

The so-called “institutes for international education” make up another type of research institution. These are graduate schools focused on international research and exchange with developing countries, some of which are housed at universities. Examples include the prestigious Royal Tropical Institute in Amsterdam and the UNESCO-supported IHE Delft Institute for Water Education, which is said to be the “the largest international graduate water education facility in the world [85].”

Universities of Applied Sciences (Hogescholen)

Universities of applied sciences, on the other hand, offer more practically oriented programs that usually incorporate industrial internships and prepare students for careers in specific fields. These institutions have traditionally only awarded four-year HBO degrees that were classified at a lower level than university qualifications and did not provide access to doctoral programs. However, since the implementation of the Bologna reforms, universities of applied sciences are now allowed to award master’s degrees, but not doctorates.

While universities generally require the VWO for admission, hogescholen – which are sometimes also called HBO institutions – can be entered on the basis of the HAVO. HBO programs have become an increasingly popular study option in recent years – there are now 15 universities of applied sciences with more than 10,000 students, with the largest of these institutions – the multi-campus Fontys University of Applied Sciences – enrolling close to 44,000 students [86]. About 10 percent of HBO students study part-time [87].

Quality Assurance and Accreditation

In line with the goals of the European Bologna reforms, which called for the creation of independent external accreditation agencies in higher education, the Kingdom of the Netherlands and the Flemish region of Belgium (Flanders) in 2003 signed a treaty that established the joint Accreditation Organization of the Netherlands and Flanders (Nederlands-Vlaamse Accreditatieorganisatie –NVAO [88]). Headquartered in The Hague, NVAO is an independent organization funded by both governments. However, despite its status as a binational institution with very similar functions in both the Netherlands and Flanders, NVAO’s concrete role is defined by national legislation, so that there are some variations in NVAO’s scope and authority between the two jurisdictions.

In the Netherlands, quality assurance in higher education is provided by both NVAO and the Dutch Education Inspectorate, which oversees the overall system. While the Inspectorate does not supervise NVAO, it monitors the overall functioning of the accreditation system, conducts complementary quality audits of government-funded institutions, and sets legal minimum standards in areas like admissions, examination regulations, and core subjects taught in particular programs [89].

NVAO program accreditation is not mandatory, but only accredited programs are eligible for government funding and public student loans. Accreditation is based on the assessment of self-evaluation reports and on-site inspections. Quality indicators include appropriate curricula and learning outcomes, teaching staff, facilities, the success rates of students in existing programs, and other criteria [90].

Accreditation is granted for a period of six years, although NVAO may limit accreditation to a conditional two-year period in the case of shortcomings in newly established programs. All accredited programs are listed in a Central Register of Higher Education Study Programs (CROHO [91]). New private HEIs that seek recognition as institutions with degree-granting authority in the Netherlands must subject their programs to initial accreditation by NVAO, in addition to obtaining a positive recommendation from the Dutch Inspectorate of Education [92]. NVAO is currently implementing a pilot project [93] that will make it possible for institutions to apply for institutional accreditation – a model in which NVAO evaluates the internal quality assurance systems of institutions, rather than periodically accrediting each individual program.

Admission Into Higher Education

The admissions process in Dutch higher education is generally decentralized with admissions decisions made by individual institutions based on high school records and minimum grade averages, although some institutions, such as university colleges, for example, may have additional requirements like interviews or entrance examinations. Formal admissions criteria depend on the type of institution: Research universities require the VWO, but students who completed the first year of study at universities of applied sciences and earned what is called the propedeuse diploma (preparatory diploma) may also be admitted. Hogescholen, on the other hand, can be entered on the basis of the HAVO (or VWO) or a level 4 MBO qualification. Older students who lack the required academic prerequisites may in some instances be admitted on the basis of a special entrance examination (colloquium doctum [94]).

While the vast majority of programs don’t impose hard enrollment quotas, enrollment restrictions exist in a number of popular fields like medicine, dentistry, physiotherapy, or psychology. To avoid overcrowding at universities and align the number of graduates with actual labor market demand, there is a fixed annual quota (numerus fixus) of available seats in these disciplines. While the Dutch government in the past sometimes allocated these seats via lottery [95], universities are now free to select students based on grade averages and other criteria. Students seeking entry into numerus fixus programs can only apply to one university at a time each year [96]. It is likely that the number of numerus fixus subjects is going to increase in the future – a number of universities announced already in 2016 that they would have to impose greater admissions restrictions amid growing demand [97].

The Tertiary Degree Structure

Like many other European countries, the Netherlands traditionally had long, single-tier, first-degree programs, such as the Doctoraalexamen, which was awarded by research universities after four to six years of study and provided direct access to doctoral programs. However, since the adoption of the Bologna reforms, the Netherlands has completely switched to the British-patterned three-cycle bachelor-master-doctorate structure. In fact, the Netherlands is one of few countries in the European Higher Education Area that has adopted the bachelor-master structure even in professional fields like medicine, veterinary medicine, dentistry, and law – disciplines in which other European countries continue to run long, single-tier, first-degree programs (see also our article [98] on medical programs within the Bologna framework in the current issue).

The bachelor-master structure is now required by law across all study disciplines in the Netherlands, so that research universities uniformly offer three-year bachelor’s degrees, followed by master’s degrees between one and three years in length, depending on the field of study. Bachelor’s degree programs at universities of applied sciences are still four years in length, as they were before the reforms, but hogescholen now also award second-cycle master’s degrees.

Grading Scale and Credit System

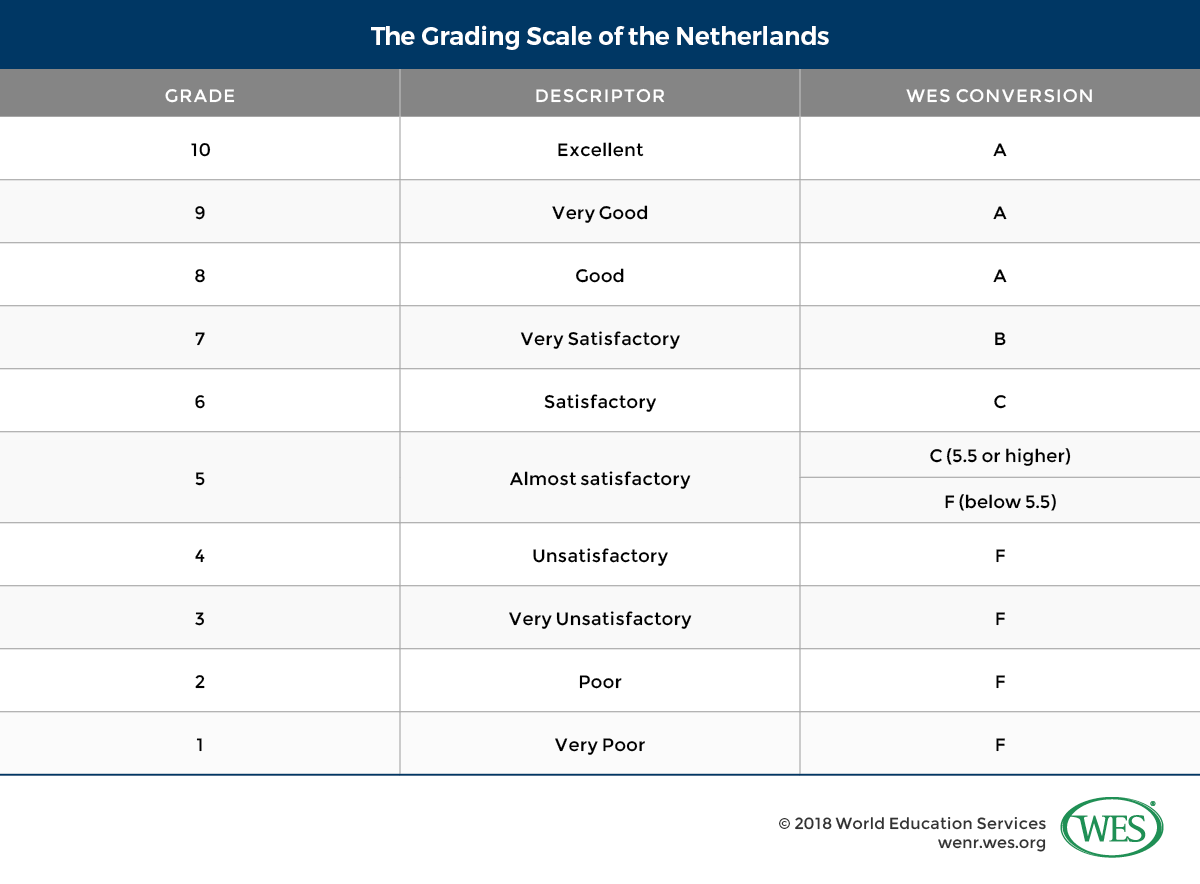

The Netherlands uses the same grading scale for all levels of education – a 10-point scale ranging from 1 (very poor) to 10 (excellent), with 6 being the minimum passing grade. It should be noted, however, that grades are often expressed in decimal points and rounded up or down in 0.5 intervals, so that a grade of 5.5 is usually considered a passing grade (since it’s rounded up to 6). The grade of 10 is almost never awarded and the grade of 9 is also highly uncommon, which means that the grade of 8 is factually a very good grade in the Dutch system [99]. A handful of higher education institutions use different grading scales, such a U.S.-style A to F scales.

Associate Degree

The Associate Degree is a relatively new and still somewhat uncommon credential in the Netherlands. It was introduced in the late 2000s as an exit qualification awarded en route toward HBO bachelor programs at the request of Dutch employers [101]. However, since January 2018, associate degrees are officially accredited as stand-alone qualifications [102] by NVAO. Programs are two years in length (120 ECTS) and typically taught solely in Dutch. They have a strong focus on specialized employment and are generally designed to offer upper-secondary VET students and others a pathway to further specialize in their vocation without completing a full-fledged bachelor’s program [65]. Admission requires a HAVO or MBO level 4 diploma. Graduates can progress into the third year of HBO bachelor programs, either immediately upon graduation or at a later date [101].

Bachelor’s Degree

The first year of bachelor programs at both research universities and universities of applied sciences is a “propaedeutic” phase designed to orient students and to assess whether students are enrolled in programs that best suit their interests and academic abilities [103]. At the end of this phase, which concludes with a final examination in some instances, higher education institutions advise students whether they should continue in their chosen program or transfer into a different one – an assessment that may be binding. Students who fail to meet the minimum requirements of the propaedeutic year are usually barred from continuing their studies [94] and terminated. Students who successfully complete the first year may be awarded a “propedeuse certificate,” although this depends on the institution and is more common at universities of applied sciences.

Bachelor’s programs at universities of applied sciences are four years in length (240 ECTS) following the HAVO or MBO level 4 diploma. Bachelor’s programs at research universities are three years in length (180 ECTS). Curricula in both HBO and university programs are specialized and impose few, if any, general education requirements. HBO curricula are practice-oriented and usually include a compulsory industrial internship of around nine months in the third year [104]. A thesis or final project is required in the final year of HBO programs and is typical in research-oriented bachelor’s programs as well.

Both types of programs conclude with a final degree examination. The most commonly awarded credentials are the Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Science, but other credentials like the Bachelor of Business Administration, Bachelor of Health, Bachelor of Nursing, or Bachelor of Laws, and so on, are also awarded.

Master’s Degree

Most graduates of academic bachelor’s programs – more than 76 percent as of 20151 [105] – enroll in a second-cycle master’s program within a year of graduating, while most HBO graduates directly enter the labor force – only 12,053 students were enrolled in master’s programs at universities of applied sciences in 2018 [106]. While qualified HBO graduates can seamlessly enter master programs at hogescholen, they must complete a bridge program of six months or longer [107] to enroll in master’s programs at research universities, where an academic bachelor’s degree is the standard minimum admission requirement. Some of these bridge programs may already be completed during enrollment in an HBO bachelor program (so-called “circuit programs [108]”). However, because of the increasing selectivity of research universities and other factors, the number of HBO graduates transitioning into graduate research programs has decreased significantly in recent years [109].

Master’s programs have a minimum duration of one year (60 ECTS), but there are also many programs that are one-and-one-half or two years in length (90 ECTS and 120 ECTS), notably in the natural sciences. Master’s degrees in professional disciplines like medicine take three years to complete (see below). Graduation generally requires completion of a research thesis or final project and a passing score on a final examination. The most commonly awarded credentials are the Master of Arts and Master of Science, but there are also several other credentials, including the Master of Business Administration, Master of Social Work, or Master of Education, and so on.

Doctoral Degree (Ph.D.)

Doctoral degrees are terminal research degrees that are awarded only by research universities. Most doctoral programs are three or four years, but it frequently takes candidates five or more years [110] to graduate. While some programs have a course work component, many programs are pure research programs completed by defending a supervised dissertation. Admission is based on a master’s degree (or older long-cycle university degree) and, crucially, acceptance of a candidate’s research proposal by a dissertation supervisor (typically a full professor), as well as approval by the faculty’s Doctorate Board (see for example the regulations of the University of Amsterdam [111]).

In addition to research doctorates, there are some professional doctorates, most notably the Professional Doctorate in Engineering (PDEng), a two-year applied and industry-integrated program offered by universities of technology in collaboration with Dutch companies like Shell or Unilever and other multinational corporations. Formerly known as the Master of Technical Design, the PDEng is a third-cycle program, but not considered a doctoral level qualification in the Netherlands.

Education in Medicine and Other Licensed Professions

As mentioned before, the old long-cycle degrees that existed before the implementation of the Bologna reforms in the Netherlands have been phased out even in the professions [110]. The University of Groningen was the first institution in the European Higher Education Area to introduce two-cycle programs in medicine in 2003 (see also our related [98] article in the current issue). This model has since been adopted by all eight University Medical Centers, which are the dedicated institutions for medical education in the Netherlands.

The old six-year medical program has been divided into two stages, the first one being a three-year Bachelor of Science in Medicine program (180 ECTS) that combines basic pre-medical sciences with a brief hospital-based internship and introductory studies in clinical medicine, but also includes a thesis and strives to achieve more general learning outcomes, such as communication and research skills [112]. In order to practice as medical doctors, students must then also complete a three-year Master of Science in Medicine program that concentrates exclusively on clinical medicine. The majority of students that complete the medical bachelor’s program continue on to the master’s stage. Holders of bachelor’s degrees in health-related disciplines like pharmacy or psychology are eligible for admission into the medical master’s program after completing a one-year bridge program.

The degree structure in other professional fields like dentistry, veterinary medicine, and pharmacy is similar to the one in medicine and now also follows a 3+3 system. Obtaining an entry-to-practice qualification in architecture involves completion of a three-year Bachelor of Architecture degree, followed by a two-year master’s degree and a compulsory professional traineeship. Only candidates that complete the traineeship can register in the Dutch register of architects [113] and use the protected title of Architect [114].

In law, students must earn a three-year Bachelor of Laws (LLB) degree and a Master of Laws (LLM) degree of at least a year’s duration. To be admitted to the Dutch Bar Association [115] and practice in one of the so-called “toga professions” (lawyers, judges, prosecutors), candidates must also complete three years of apprenticeship training and pass additional examinations [116].

Teacher Education

There is a desperate teacher shortage in the Netherlands. The shortage is so severe that some schools recently shortened their school week to four days [117], while the city of Amsterdam is transferring civil servants who hold teaching qualifications into school service and has begun to train qualified Syrian refugees to work as teachers [118]. Recent school surveys showed that elementary schools in the country were short 1,300 teachers [119] – a deficit the government expects to grow to more than 10,000 by 2027 [120]. To combat this shortage, the Dutch government has adopted measures like increasing teacher salaries [121] and incentivizing students to enroll in teacher training programs with tuition subsidies [122].

The academic qualifications required to work as a teacher in the Netherlands vary by level of education and are classified into three types of teaching authorizations (onderwijsbevoegdheden [123]). Elementary school teachers (grades 1 to 8) require a Bachelor of Education that is earned at dedicated teacher training colleges (Pedagogische Academie Basisonderwijs – PABO), which are typically part of the HBO sector, but PABO programs may also be offered by some universities [124]. Programs are four years in length (240 ECTS), include a propaedeutic year, and incorporate a six-month in-service teaching internship in the final year [125]. A HAVO or VWO diploma is required for admission.

Teachers at the lower-secondary level (the foundation phase of HAVO/VWO programs and VMBO) require a “second-grade” teacher qualification (leraar tweedegraads), which is also a four-year bachelor’s program, requiring the HAVO, VWO, or MBO-4 for admission. Programs are mostly offered by universities of applied sciences, but also by universities. Teachers are only authorized to teach in the specific subjects in which they received training. Like all teacher training programs in the Netherlands, second-grade programs include a practice teaching component. An alternative pathway for obtaining a second-grade teaching qualification is completing a one-year “top-up” program after earning a bachelor’s degree in the subject specialization in which students intend to teach [126].

Upper-secondary teachers, on the other hand, must have a “first-grade” teacher qualification (leraar eerstegraads), which is obtained by completing a master’s degree (at either a university or university of applied sciences [127]). Master of Education programs are two years in length, but students who already have a master’s degree in another discipline can earn a master’s degree in education in just one year [128]. There are also lateral entry options for teachers to obtain a certification in additional teaching subjects, as well as other lateral pathways [129] at different levels of education to make it easier to educate and recruit teachers. In general, the Dutch government seeks to elevate teaching quality by requiring teachers to engage in continual professional development [130] and by increasing the number of teachers who hold a master’s degree [131].

WES Document Requirements

Secondary Education

- Graduation Certificate (Diploma HAVO, Diploma VMO, Diploma VMBO, etc.) – sent directly by the institution attended

- Precise English translation of all documents not issued in English – submitted by the applicant

Higher Education

- Degree Certificate (Bachelor, Master, Getuigschrift Hoger Beroepsonderwijs, Doctoraalexamen) – submitted by the applicant

- Diploma Supplement (or academic transcript for incomplete programs) – sent directly by the institution

- For completed doctoral programs, a letter confirming degree conferral – sent directly by the institution

Note: WES requires that applicants submit precise English translations of all documents not issued in English. For more information on WES documentation requirements, please visit our website [132].

Sample Documents

Click here [133] for a PDF file of the academic documents referred to below.

- Diploma voorbereidend wetenschappelljk onderwijs (VWO)

- Diploma middelbaar beroepsonderwijs (MBO)

- Associate Degree

- Bachelor of Business Administration (HBO)

- Bachelor of Education (HBO)

- Bachelor of Science

- Master of Business Administration

- Master of Science

- Bachelor of Science in Medicine

- Master of Science in Medicine

- Doctor (Ph.D.)

1. [134] According to data provided by Dutch authorities and institutions in a Dutch National Report regarding the Bologna Process implementation, 2012-2015. See: http://www.ehea.info/media.ehea.info/file/Netherlands/84/0/National_Report_Netherlands_2015_571840.pdf [135]