Alejandro Ortiz, Senior Research Associate, WES, and Jean Cui, Research Associate, WES

Canada has positioned itself as an immigration-friendly country with its favorable immigration policies, numerous settlement and citizenship programs, and welcoming environment [1]. A recent report [2] published by Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) proposes to increase immigration even further. The country is projected to welcome 1.3 million newcomers between 2018 and 2021 [3]. A top international destination for highly skilled workers [4], Canada in 2017 admitted 286,479 permanent residents.

The implementation of the new immigration system Express Entry [4] will most likely affect the way potential skilled immigrants view and approach immigration to Canada. Understanding the nature of perceived barriers to immigration and creating appropriate programs and incentives for new immigrants are vital as Canada continues to seek the best possible applicants—those with the skills the country needs—and thereby position itself for the future.

What Is Express Entry?

Canada, along with a few other countries (Australia and New Zealand), recently updated its immigration policies through the implementation of an Expression of Interest [4] system—in Canada’s case, Express Entry [5]. Express Entry “replaces the first-come, first-served method of processing applications traditionally used by major destination countries”1 [6] like the United States. Express Entry is now Canada’s flagship immigrant management system [7], designed in part to address Canada’s technical skills gap [8] while assertively embracing the challenges of a labor market in need of highly skilled professionals [9].

Besides the elimination of the first come, first served policy, there have been a few other changes since the launch of the Express Entry system. For example, prospective immigrants previously applied directly to the immigrant program they thought was the best fit. Now, applicants first submit an online profile, and the Express Entry electronic application management system automatically slots them into the immigration program that is most appropriate for them.2 [10]

Another change is that Canadian employers can now use Job Bank [11], an online portal, to post jobs and find potential candidates through the immigrant pool. Applicants who receive a job offer are awarded extra points. The points-based system, or Comprehensive Ranking System (CRS) [12], is a critical feature of Express Entry. As its name implies, CRS ranks applicants in the pool based on their education, skills, and experience, among other characteristics.

About the Data

Since 2013, World Education Services (WES)—along with other educational assessment organizations [13]—has been designated by IRCC to provide educational credential assessments (ECA) as part of the skilled immigrant application process. Through immigrants’ applications to WES for an ECA, WES has learned more about prospective skilled immigrants to Canada, an understudied group that is difficult to reach, by surveying them for the past four years.

WES survey data compare the characteristics of the applicants before and after the introduction of Express Entry. Express Entry is fairly new, and analyzing its effects on the immigrant pool is of particular interest to WES and to anyone concerned with successful immigrant integration.

Method

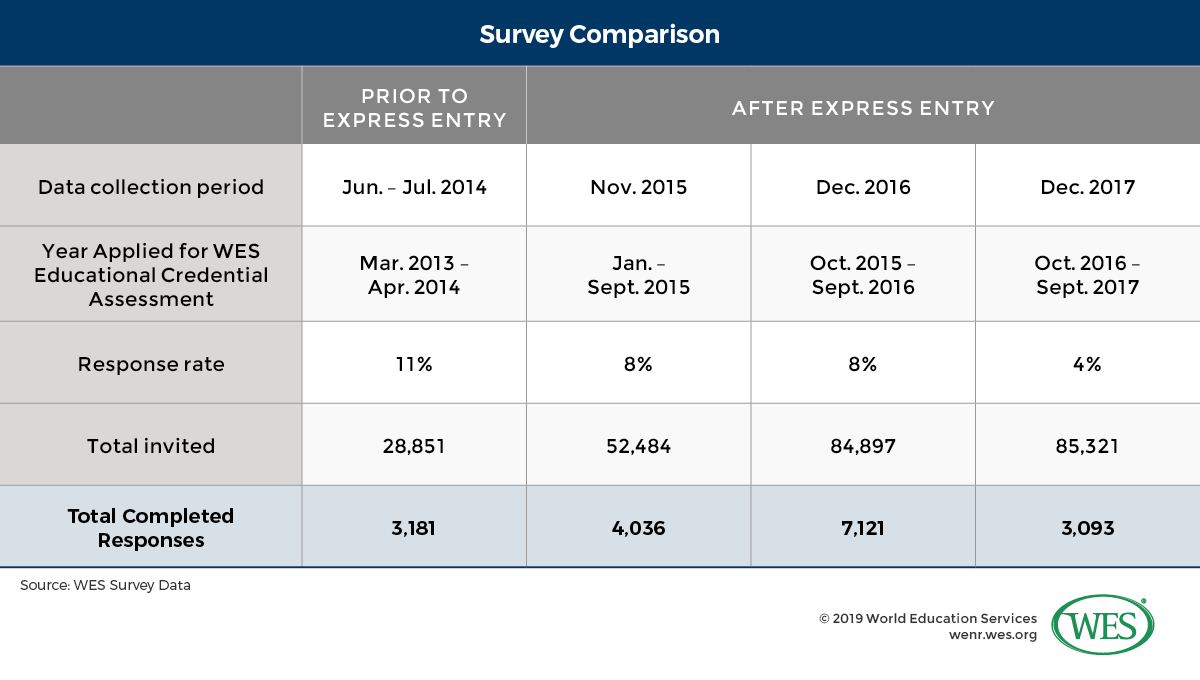

WES has surveyed IRCC-ECA applicants for the purpose of better understanding their migration motivations, career and education plans, perceived barriers to success, and service needs. WES has surveyed the applicants every year since 2014; the average response rate is 8 percent.

How representative are WES Data?

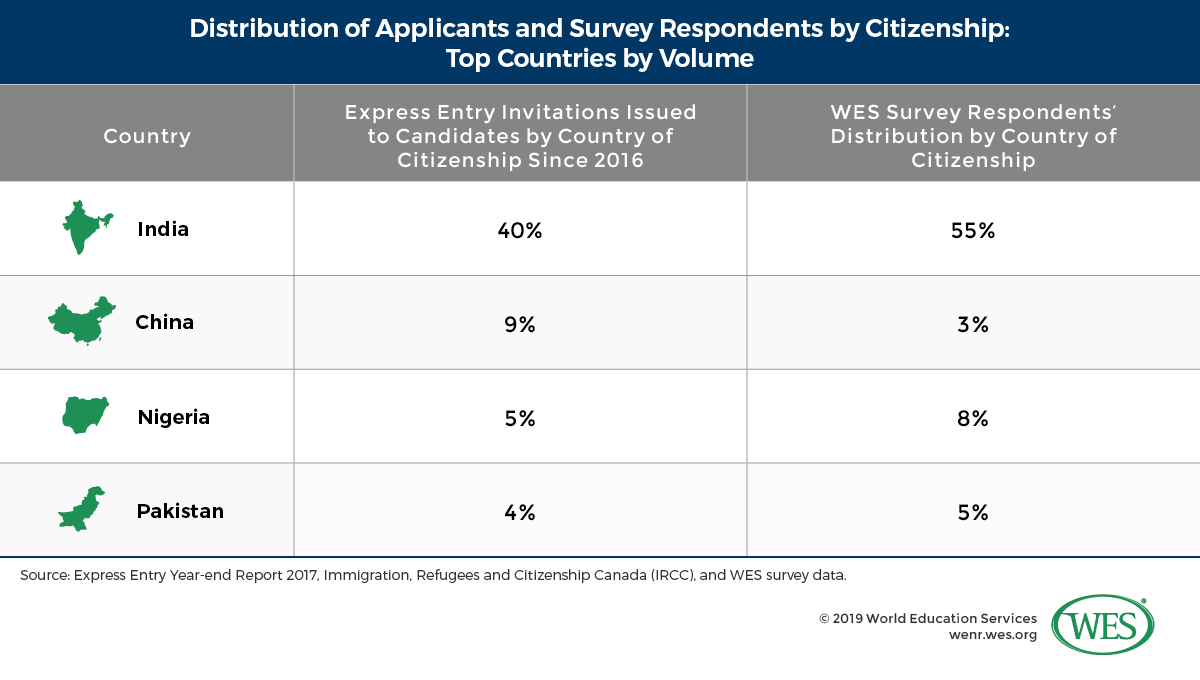

The Canadian government has produced several reports about Express Entry [7] since the program’s implementation. By comparing WES data against publicly available Express Entry data [7], we can identify how approximate WES data are to that of Express Entry. For example, in terms of top countries of citizenship, WES has the same top four countries as those in the Express Entry pool of invitations to apply (the closest proxy group for which Express Entry discloses information by citizenship).

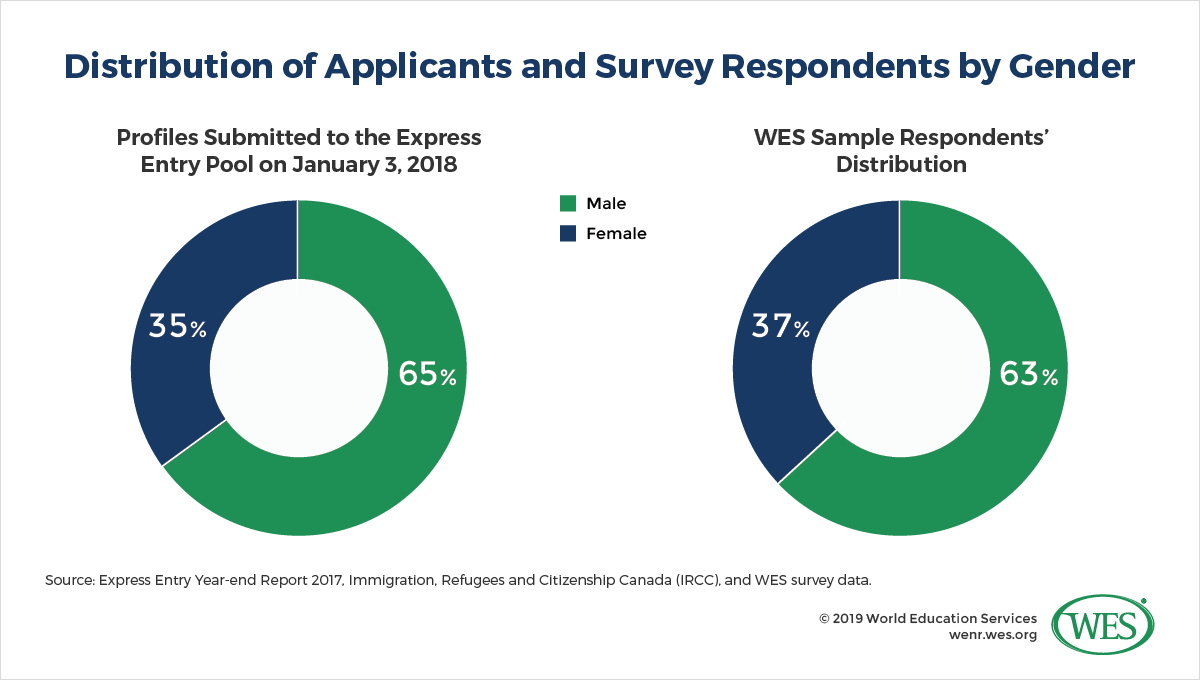

WES data are also similar to Express Entry’s regarding the percentage of men and women who responded. WES respondents are 37 percent female, while 35 percent of Express Entry profiles submitted to the pool as of January 2018 are from females.

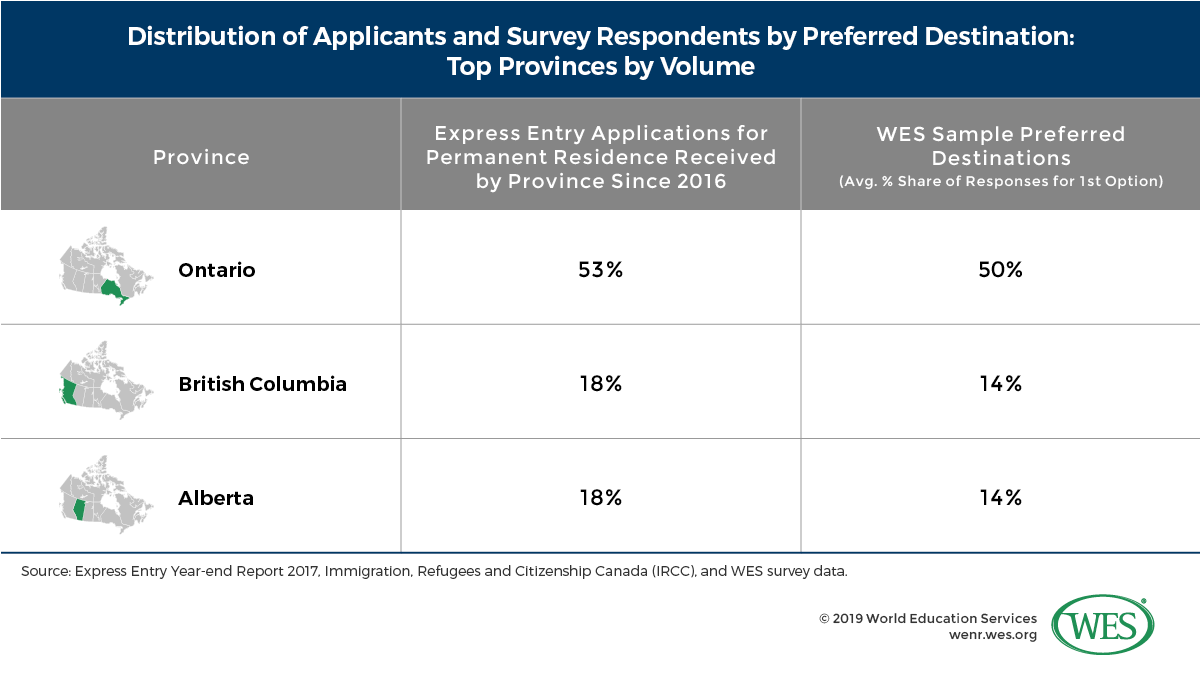

WES survey respondents also expressed similar preferred destinations,3 [16] indicating Ontario as their first choice (50 percent), followed by British Columbia and Alberta (14 percent each). The top provinces to receive Express Entry applications for permanent residence since 2016 have been Ontario (53 percent), trailed by British Columbia and Alberta (18 percent each).

Findings

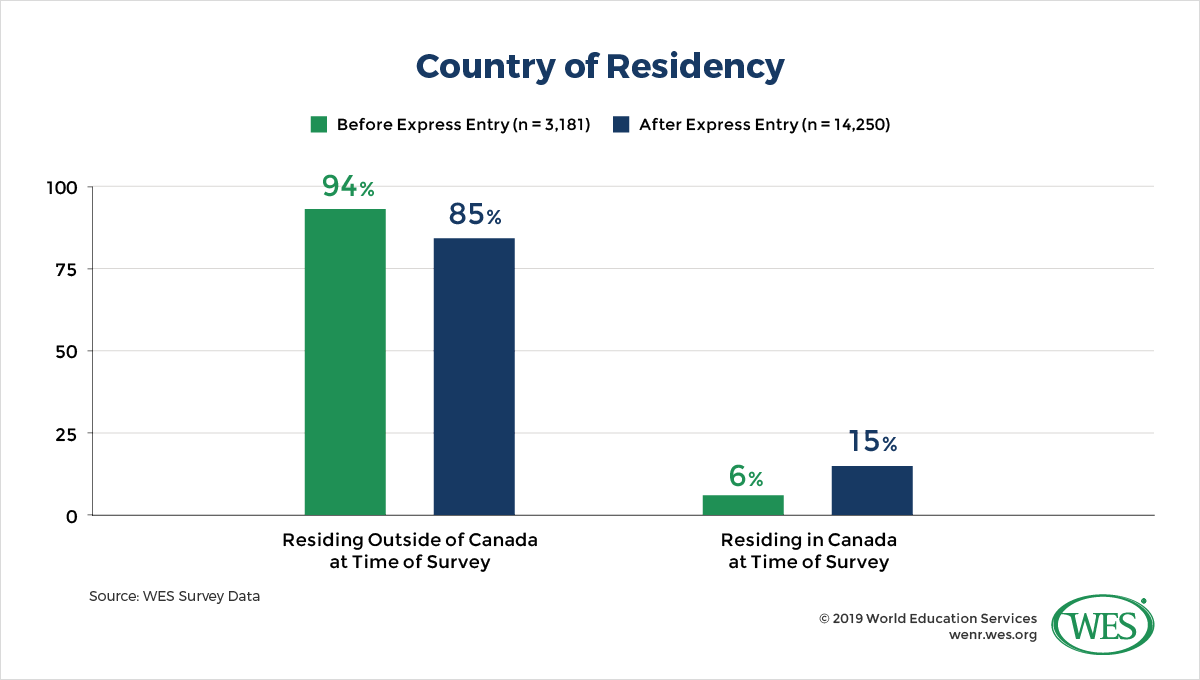

Our data indicate certain demographic changes in the applicant pool, specifically that more single people are applying, that married people are applying more strategically, and most significantly, that more applicants are already residing in Canada.

First, a growing number of single adults are applying to immigrate to Canada. This increase in the number of single applicants could be due to the greater number of applications from international students transitioning to permanent residency. This finding agrees with recently reported data [19], indicating a growth of 14 percent in the number of permanent residency applications from international students.

We found that married applicants are more likely to have their spouse post an Express Entry profile as well. Under the current Express Entry system, an additional 40 CRS [20] points are given to those who add a spouse to their profile—if the spouse has excellent education qualifications, language proficiency (in English or French, the two official languages of Canada), and Canadian work experience. Another strategic approach taken by some married applicants is to double their presence in the Express Entry pool by both applying as principal applicants [21].

Our survey results also indicate that after the implementation of Express Entry, more applicants were already residing in Canada. Previously, the Federal Skilled Worker Program received the bulk of applications on a first come, first served [23] basis. Express Entry, however, puts applicants already residing in Canada at an advantage, because their Canadian work experience and language skills give them more points for a higher CRS score. This finding implies a potential shift from the previous applicant pool and indicates that with the implementation of Express Entry, temporary residents like international students and temporary workers are starting to seriously consider applying for Canadian citizenship via Express Entry.

Perceived Barriers

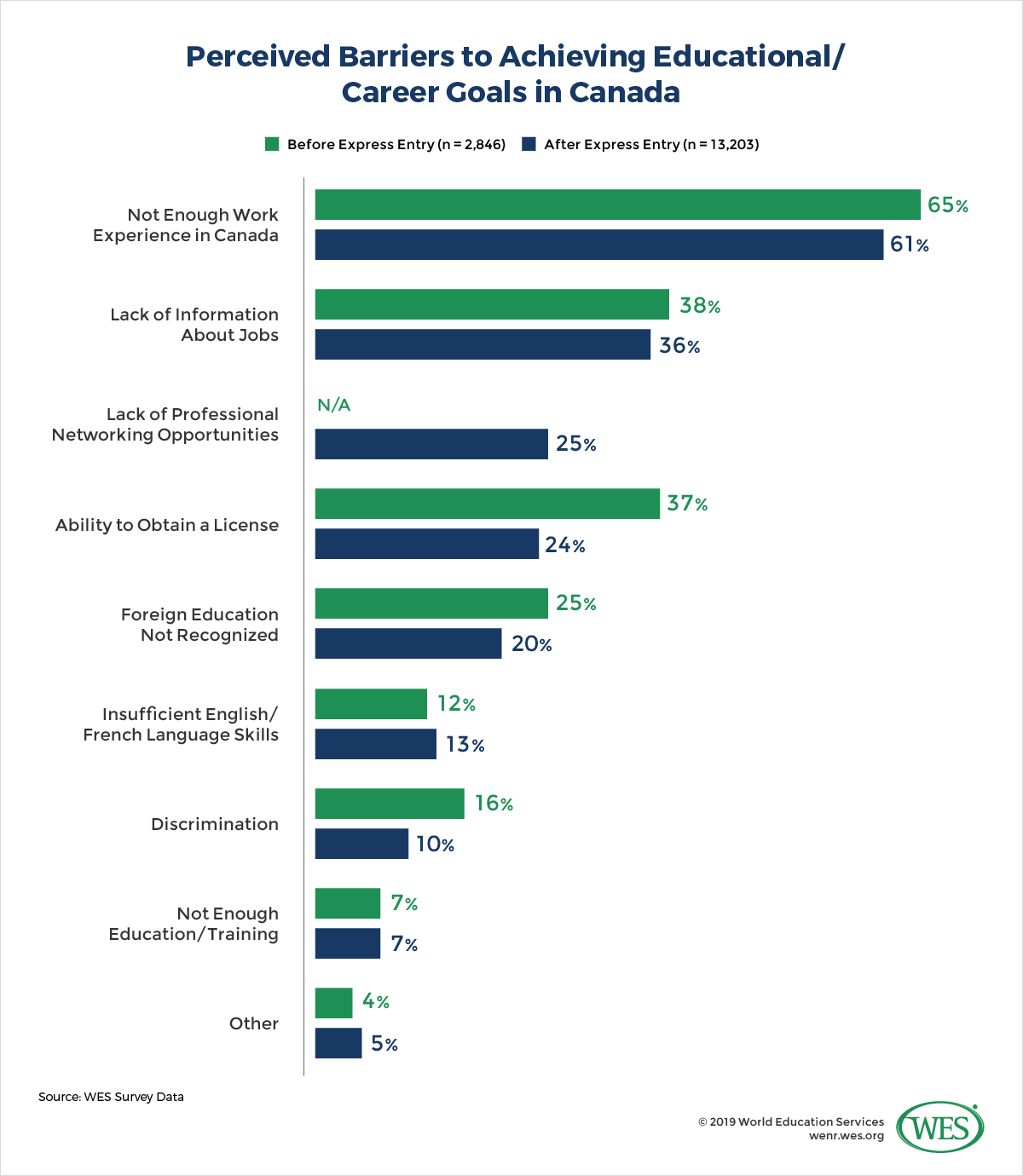

The WES surveys also asked about applicants’ top perceived barriers to achieving their goals in Canada. In the surveys of the past four years, before and after Express Entry, “not enough work experience in Canada” has remained the main barrier immigrants expect to encounter. Aware of the challenges, the Canadian government has funded organizations and settlement agencies [24] that provide services to newcomers in language training and information and referrals, and that match newcomers’ skills with employment and integration into Canadian society.

Equally noteworthy is the fact that the primary drivers for applying for Canadian immigration have remained steady throughout the years: A better standard of living, career opportunities, and educational opportunities for themselves and their children continue to be the top motivations for immigrating to Canada.

Source: WES survey data5 [26]

Awareness of Programs for Immigrants

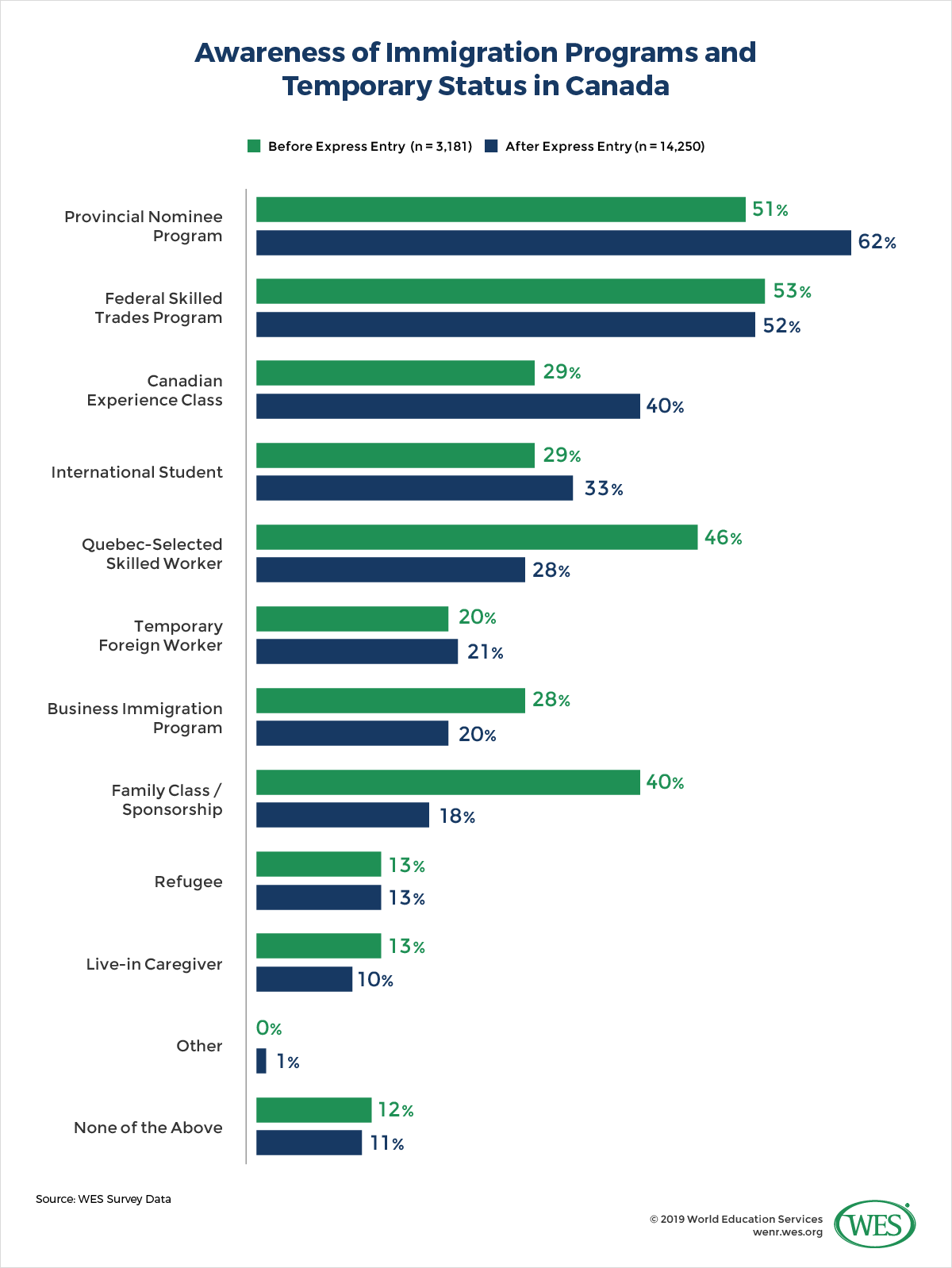

Overall, applicants who reside in Canada are more aware than their counterparts of two specific programs for immigrants: the Canadian Experience Class (CEC) and the Provincial Nominee Program (PNP). The CEC requires candidates to have at least 12 months of full-time skilled work experience within the past three years before they apply.

The individual provinces, except Quebec [27], manage PNPs, which have their own points policies [7] through which applicants can gain up to 600 additional points, 200 of which can be gained through qualifying arranged employment. The increased awareness of this program and its consequent surge in applications is worth noting. Through PNPs, Canadian provinces are openly competing for highly skilled labor.

To address the labor shortages of those provinces that may be less attractive to prospective immigrants, the Canadian government has launched a variety of programs and initiatives. For example, the Atlantic Immigration Pilot [28] program seeks to attract more than 7,000 skilled immigrants [29] to the Atlantic region by 2020. Thus far, the results have been promising [30].

Location Preferences

For the past four years, our surveys asked about applicants’ preferred destinations, and each year the number citing Ontario as their top destination has increased. Ontario is “at its top speed” [32] issuing invitations under Express Entry via two streams: Skilled Trades and French-Speaking Skilled Worker, which has no minimum CRS score. In recent invitation rounds, Ontario selected Express Entry candidates who had CRS scores as low as 351, although the province “requires” CRS scores of 400 and above [33], on average.

Another province that has seen an increase in applications is Saskatchewan [34]. The province’s new Expression of Interest system [35] creates a “deeper pool of candidates” through the Express Entry subcategory. It also considers candidates who do not have a job offer. This system benefits applicants who reside outside of Canada, as well as those who have no previous Canadian work experience, since it can be quite challenging for these two groups to secure employment offers. In the past decade, Saskatchewan has retained more than 80 percent of its skilled workers; in the past two decades, immigration in general has increased the province’s population by roughly 1.5 percent.

The province of Alberta formerly outperformed many other provinces [36] in the PNP. It had the highest retention rates, due to Alberta’s flexible policies. For example, the province is one of three that accept applicants who do not have job offers. Immigrants to Alberta enjoy the highest employment earnings in their first five years following admission. Now that competition with the other provinces has increased, however, PNP applications to Alberta are down 10 percent.

Conclusion

Policy changes can have a profound and long-lasting impact, both in the region where they are implemented and on the immigrant hopefuls that they affect. In our examination of Express Entry, we identified changes in the applicant pool before and after its introduction. The most significant was that more applicants are already residing in Canada.

More research is needed to develop a better understanding of the effects of Express Entry. For example, what are the employment satisfaction and labor market outcomes of those who gain permanent residency and who are currently employed? What do underemployed people do in an effort to make full use of their academic credentials? To address such questions, WES will conduct further research, with the aim of providing valuable and timely information on successful immigrant integration.

1. [37] Maria Vincenza Desiderio and Kate Hooper, The Canadian Expression of Interest System: A Model to Manage Skilled Migration to the European Union? (Brussels: Migration Policy Institute Europe, 2016).

2. [38] Lotf Ali Jan Ali, “Welcome to Canada? A Critical Review and Assessment of Canada’s Fast-Changing Immigration Policies” (RCIS Working Paper 2014/6, Ryerson Centre for Immigration and Settlement, Ryerson University, Toronto, 2016).

3. [39] What is your intended destination in Canada? The question was then modified to, which are your preferred destinations in Canada? (Select top 3) in the fourth and fifth iterations of the survey, launched in 2016 and 2017, respectively.

4. [40] What is your intended destination in Canada? The question was then modified to, which are your preferred destinations in Canada? (Select top 3), in the fourth and fifth iterations of the survey, launched in 2016 and 2017, respectively.

5. [41] “Lack of professional networking opportunities” was not an option for applicants taking the survey before the implementation of Express Entry. The “not applicable” option was removed from the analysis. Percentages were generated based on response count instead of choice count. Results apply only to applicants at the application stage.