Makala Skinner, Research Associate, WES, and Chris Mackie, Research Associate, WES

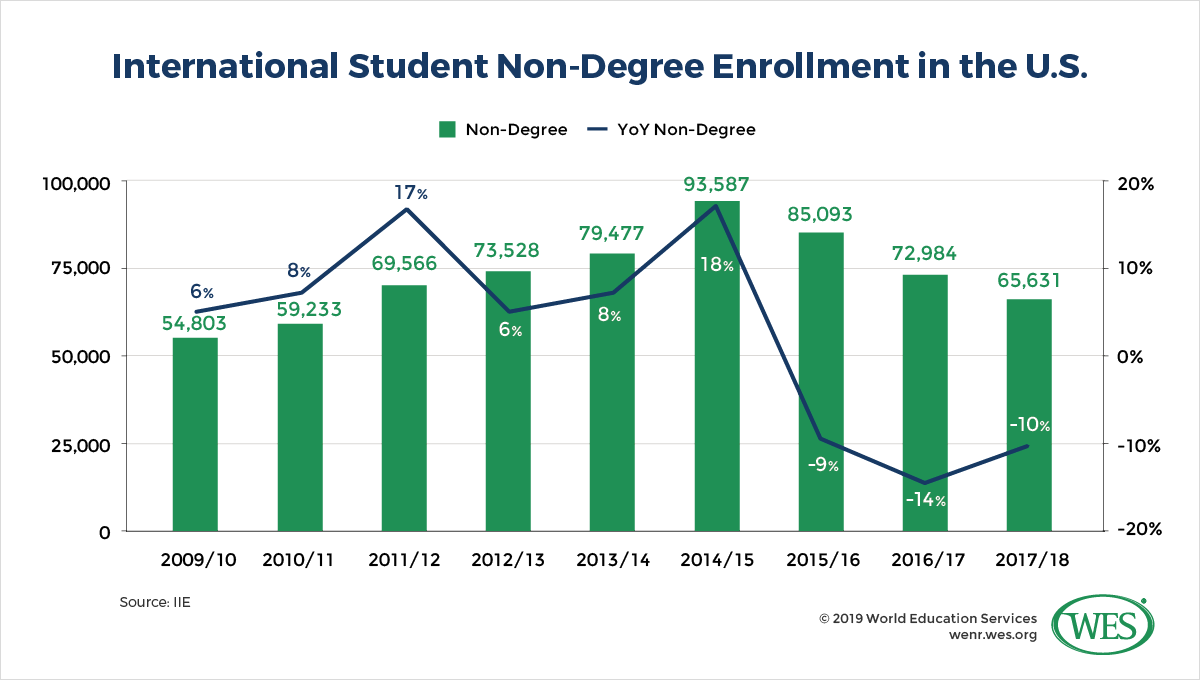

Declines in new international student enrollment in non-degree programs in the United States are being felt acutely. Enrollments plummeted by nearly 10 percent in 2017/18 [1], dropping for the third straight year. The result of diminishing financial support from foreign governments, these declines particularly affect enrollment numbers from countries that traditionally send high numbers of non-degree students to the U.S. Saudi Arabia and Brazil accounted for 29 percent of all non-degree students in the U.S. at the height of non-degree enrollment in 2014/15. Changes to and suspensions of large-scale government scholarships within the two countries have significantly affected Saudi and Brazilian students, as well as the non-degree arena at-large.

Non-degree Students

IIE defines non-degree students as “exchange students, students in certificate programs, continuing education students, non-credit students and all other international students enrolled at…[an] institution that are not pursuing a degree [2].” These students come to the U.S. and for myriad reasons enroll in extension schools, continuing education programs, or individual classes. Improving English language ability, learning skills to position themselves for career changes, earning credentials to advance within their profession, and learning something new for its own sake are all top reasons for international students to pursue non-degree courses or programs.

IIE’s Open Doors separates non-degree data into two categories:

- Non-degree Intensive English: international students enrolled in a non-degree intensive English course or program at an accredited, degree-granting higher education institution (HEI)

- Non-degree Other: international students enrolled in any non-degree course or program (other than intensive English) at an accredited, degree-granting HEI

Non-degree Program Benefits

Transfer credit: International students may be able to earn credits in non-degree courses and transfer them to degree-granting programs later on, depending on the design and structure of the program as determined by the HEI. Some credits are eligible for transfer to U.S. institutions, while others may be transferable to international HEIs.

OPT: Some non-degree certificate programs allow students to take advantage of Optional Practical Training depending on their length. International students who complete year-long certificate programs are eligible to apply for OPT.

Affordability: Non-degree courses and programs have the added appeal of being comparatively short, which can make both the opportunity cost of pursuing education as well as the tuition bill itself more manageable for many students.

Non-degree Enrollment Trends

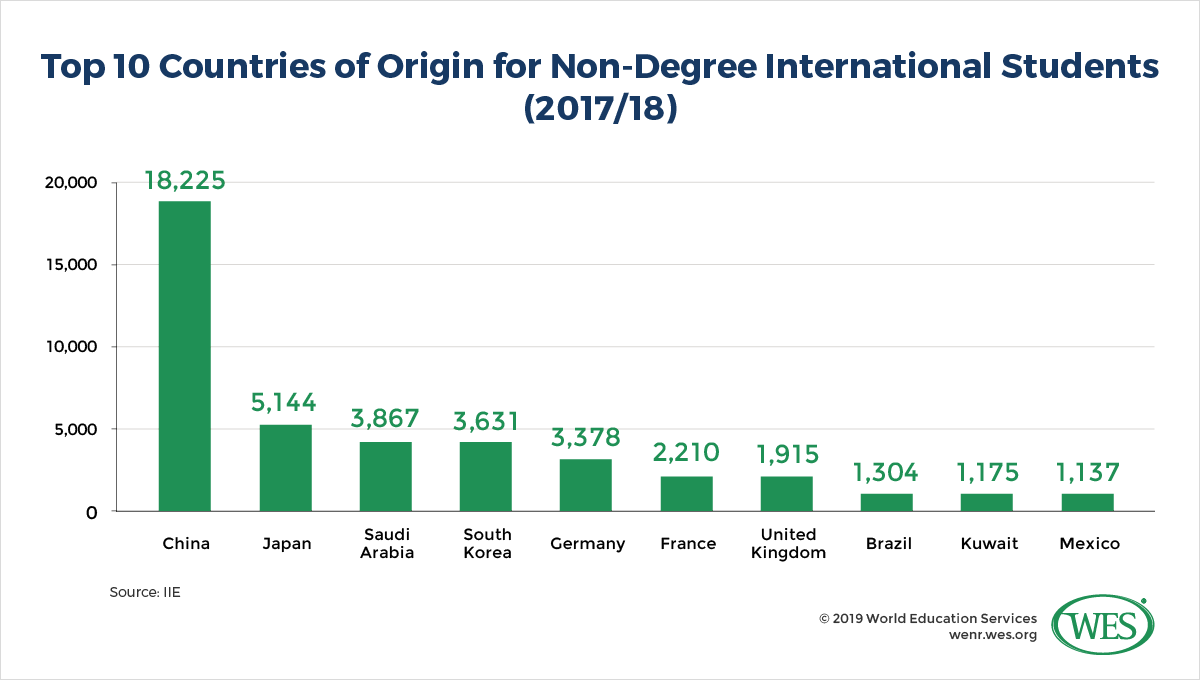

In the U.S., international students who enroll in non-degree programs are primarily from 10 countries (see Figure 1), which make up nearly two-thirds of all non-degree enrollment. From its height in 2014/15 (93,587 students), non-degree enrollment has shrunk by nearly a third to just 65,631 students in 2017/18 (see Figure 2).

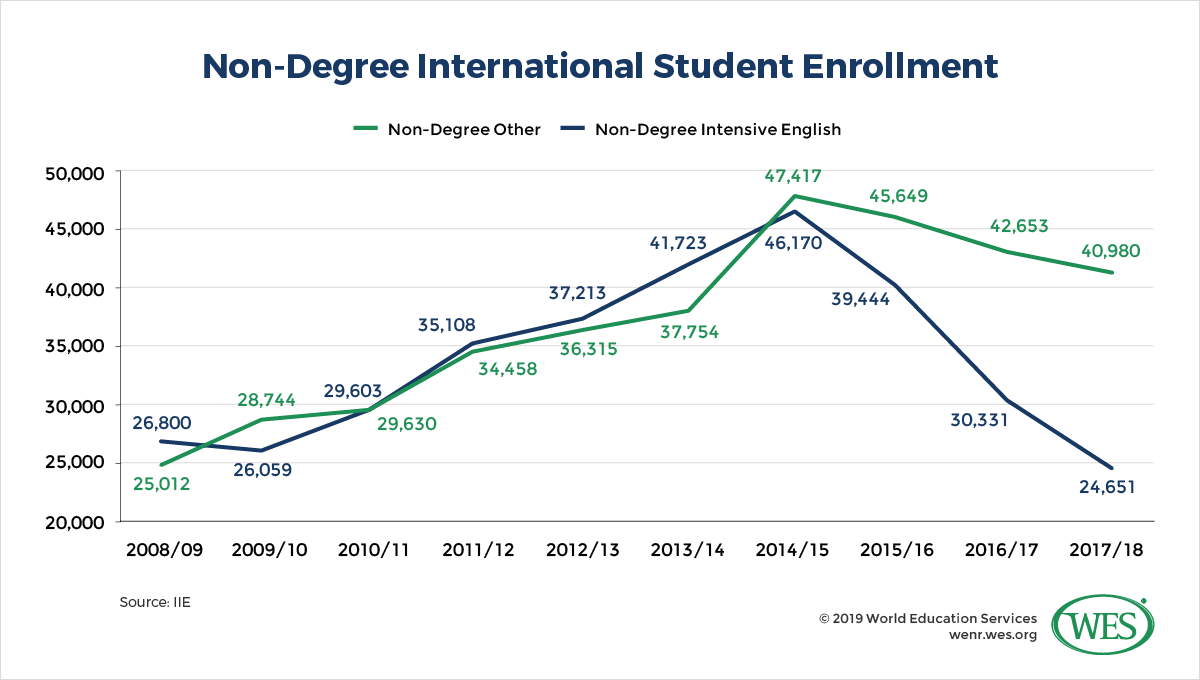

When non-degree enrollment data are disaggregated into IIE’s two categories—Non-degree Other and Non-degree Intensive English—it becomes clear that enrollment in Non-degree Intensive English programs is falling precipitously (see Figure 3). In just three years, Non-degree Intensive English enrollment has been reduced nearly by half, while Non-degree Other enrollment has slowed more gradually.

The Importance of Funding Sources

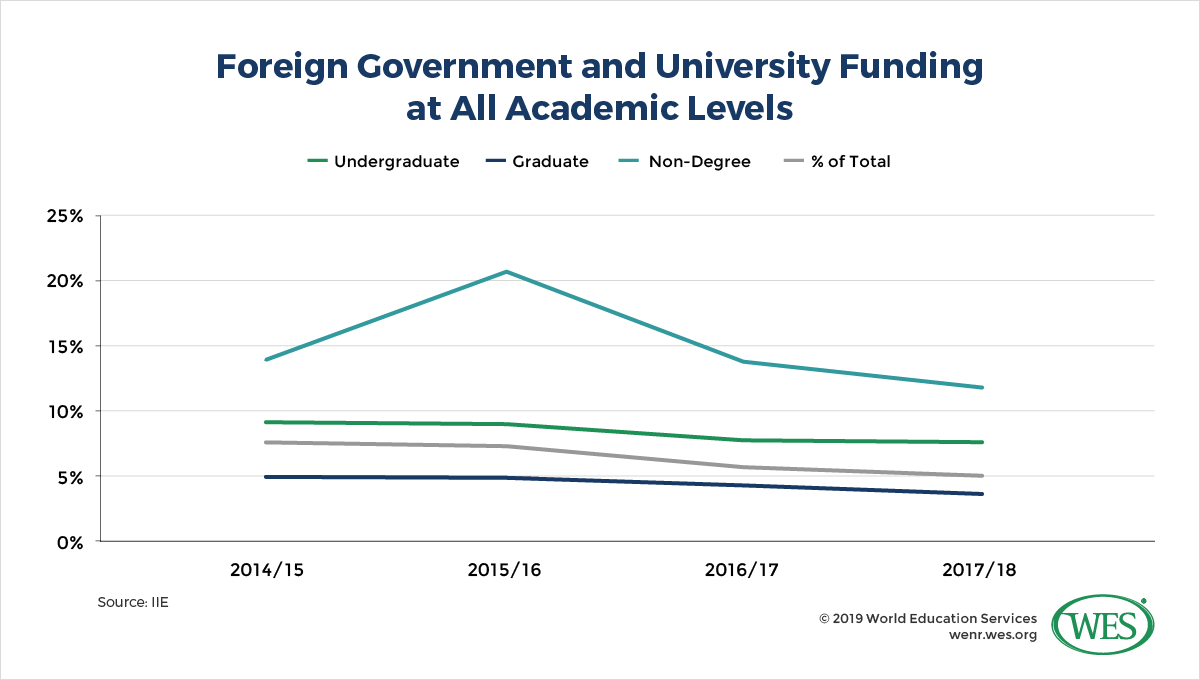

International students fund their education [6] in the U.S. through a variety of means, including personal and family savings, foreign or domestic scholarships, and employee sponsorship, among others. A key international funding stream is foreign government or university scholarships. In recent years, this funding source has played a proportionately greater role in financing study at the non-degree level than at the undergraduate or graduate level (see Figure 4).

This vulnerability was highlighted by the dramatic declines in non-degree enrollments which immediately followed budgetary cuts to the scholarship programs of both Saudi Arabia and Brazil. “If it’s a government program, a university program, or a program depending upon a particular political regime, you can see discreet, but potentially large swings in portions of your student population [when that funding is eliminated],” noted Tom Oser, interim vice provost at Continuing Education and UCLA Extension in an interview with World Education News & Reviews.

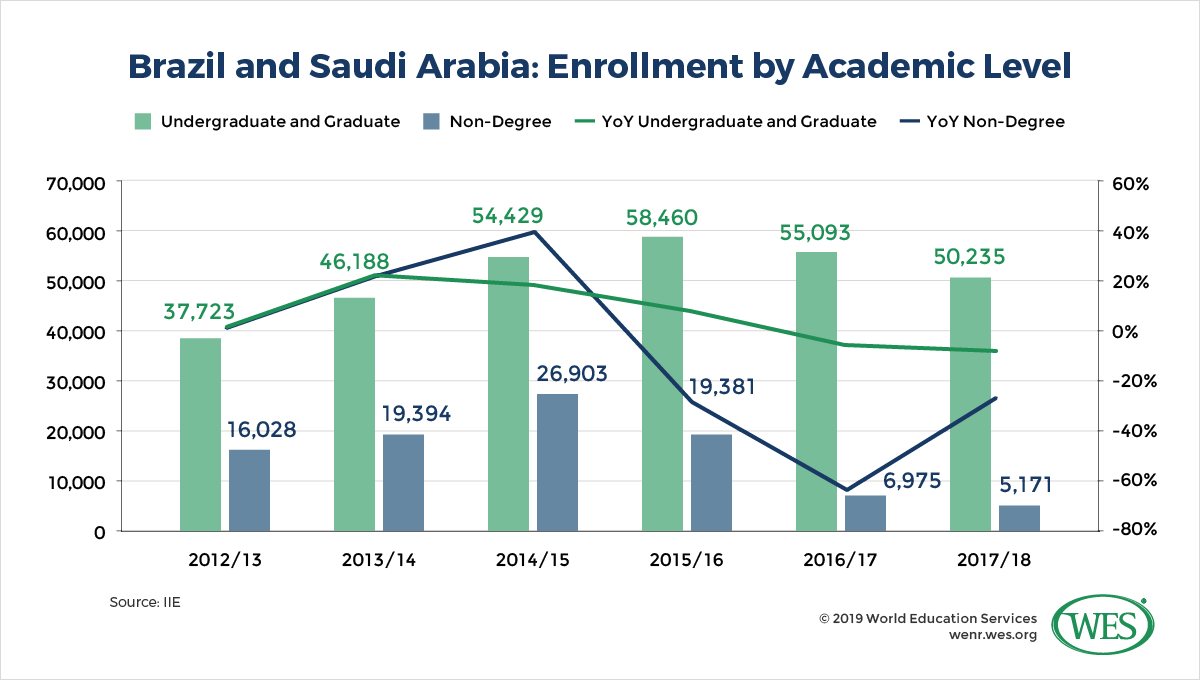

In fact, the sharp decline in total non-degree enrollment in the U.S. is primarily attributable to these two countries. Combined, Saudi Arabia and Brazil account for 78 percent of the decline in student enrollment. Saudi Arabia accounts for about 41 percent, and Brazil, for roughly 37 percent. Changes in large-scale scholarship programs in both countries have coincided with the sharp decline.

Saudi Arabia

In early 2016, the Saudi Arabian government announced changes in the eligibility requirements of the King Abdullah Scholarship Program (KASP) [8], now known as “The Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques Scholarship Programme.” These changes were spurred by declining oil prices worldwide and consequent budgetary shortfalls [9], which hastened a refocusing of the scholarship on the quality of the education that recipients received over the quantity of scholarships issued. In light of this new emphasis on quality, scholarship funds were now redirected toward current and prospective public sector employees, with the goal of developing the nation’s human capital resources. While there is uncertainty [10] surrounding some of the changes, their effects are obvious enough.

The changes depressed Saudi Arabian enrollment across all education levels, but they slashed the enrollment numbers of non-degree students. In fact, immediately after the changes went into effect, non-degree enrollment numbers sank by more than half (from 2015/16 to 2016/17), while undergraduate and graduate numbers declined at a much more modest 4 percent and 7 percent. Declines at the undergraduate and graduate levels did fall further this past year, reaching year-over-year declines of 15 percent and 10 percent, but they were still far outpaced by the 34 percent decline at the non-degree level.

Details of the KASP reveal mechanisms that are responsible for the uneven distribution of declines across academic levels. Saudi students planning to enroll in degree-seeking programs in the U.S. at the undergraduate or graduate level were eligible to apply for full funding through the KASP, as were those planning to apply for non-degree programs.

Most significantly, the KASP provided funding for up to 18 months of pre-academic English language training. Because of the country’s low levels of English proficiency [12], many scholarship recipients required extensive English language training before they could enroll in degree programs. According to IIE data, Saudi Arabia was the leading country of origin for students enrolled in Intensive English Programs in the U.S. from 2009 to 2015.

Since a significant number of KASP scholarship recipients enrolled in pre-academic English language programs, the initial eligibility changes and funding structure of the scholarship had a marked impact on the number of Saudi students enrolled in Non-degree Intensive English programs and courses.

The government also introduced higher academic and linguistic eligibility requirements, such as possession of intermediate level English proficiency [13], or an IELTS exam score of at least 4.0. These stiffer requirements restricted the pool of scholarship recipients to those who already had higher levels of English, thus reducing the need for extended English language training.

Perhaps even more significantly, the scholarship introduced a change in eligibility for students applying to the KASP after they had already enrolled at a U.S. institution. At the time of the change, approximately 70 percent [14] of all scholarship recipients had already enrolled in a U.S. HEI.

The revised guidelines now required a student to be enrolled in a top 200 global institution, or in a program in the top 50 of any specific academic subject, in order to qualify for scholarship funds. On a practical level, this move severely restricted the number of scholarship recipients who could enroll in pre-academic English language training, since “many of the top-tier universities in the U.S [13]. don’t have affiliated IEPs or conditional admissions set up to provide a clear pathway into degree programmes once English proficiency is demonstrated.” While these restrictions reduced Saudi enrollment across all academic levels, effects were felt most immediately and profoundly at the non-degree level.

Brazil

Likewise, after effectively suspending its Science Without Borders [15] mobility program in late 2015, total non-degree enrollments of Brazilian students plunged from their peak of 11,581 in the 2014/15 academic year to just 1,114 in 2016/17. Comparing the effects of these cuts on enrollment numbers at the undergraduate and graduate levels reveals the importance of foreign government or university funding at the non-degree level. While non-degree enrollment declined precipitously the year after the program was suspended, total enrollments at the undergraduate and graduate levels continued to grow, albeit at a slower rate than that of the previous year.

Science Without Borders was designed to increase STEM capabilities among Brazilian students. The scholarship offered funding for up to six months of pre-academic language training [16] and 12 months of [17]study at the undergraduate level, and it included an internship component. This funding was contingent on the students’ return to Brazil where they would complete their degree. The scholarship effectively functioned as a pathway for students to enter the U.S. as non-degree students; its website explicitly stated, “This is a one-year non-degree program, as students will return to complete their degrees in Brazil [18].” When the program ended, it drastically reduced the number of Brazilian students enrolling in the U.S. at the non-degree level.

Future Prospects and Strategies

The unique dependence of non-degree enrollment on foreign government or university funding leaves enrollment levels highly susceptible to shifts in global economies and policies. While these shifts and the consequent volatility in enrollment levels are outside the control of individual institutions, careful management and proactive policy initiatives can help minimize the impact of sudden declines.

Overdependence on a small number of source countries for international student enrollments carries obvious risk at all academic levels. But the risk is even more pronounced at the non-degree level, where external factors can leave institutions scrambling to recover from unanticipated declines. However, efforts to diversify the international student population can help mitigate the effects of sudden losses from any one country.

A variety of strategies can amplify diversification efforts at the non-degree level. In a recent WENR interview, Eddie West, director of International Programs at UC Berkeley Extension, emphasized the importance of establishing collaborative partnerships with overseas universities or individual academic departments.

“[The] university partner relationship cultivation piece is a big part of what we spend time on when we’re overseas,” West said. “[We engage in] the conference circuit, the fairs, and with Education USA, but those partner relationships are really our number one priority.”

Such partnerships can pay dividends, creating enrollment funnels that connect schools directly to institutions abroad. At UC Berkeley, for example, a long-standing connection between its sociology department and Norwegian universities has boosted non-degree enrollment. Outreach initiatives, such as participation in international education conferences (like NAFSA, EAIE, or APAIE) or in international student-facing fairs, can help to increase institutional visibility within the international education marketplace.

Additionally, partnerships with international agents specializing in underrepresented countries, although such partnerships carry their own risks [19], can also help boost international enrollment numbers from strategically important nations.

Furthermore, the development of short-term custom programs that are specifically designed to meet the needs of international students and mid-career professionals can help attract a broad range of prospective students. For example, specialized intensive English language courses can help attract international students looking to improve their English in a particular subject area. One such program is UCLA Extension’s legal intensive English language program, which is designed to teach law-specific English to students. These kinds of programs, which provide the foundational support necessary for students to succeed, make enrollment possible for students who might otherwise be ineligible.

Another important avenue for non-degree enrollment is the creation of short-term business or profession-oriented programs aimed at improving the competencies of mid-career professionals. With international enrollment at U.S. business schools declining, in part because of the length and cost of the traditional two-year MBA program [20], the creation of short-term, professionally focused programs can help attract prospective international students unwilling or unable to invest their time and money in a traditional MBA program.

As West explains, “I think you see this trend—that many students are looking for shorter experiences because of time and tuition and the opportunity cost it entails to get, for example, an MBA. We have one program that has been phenomenally successful for us. It’s a partnership between us and our school of business. Our fourth semester just launched, and we have close to 75 students in that program. It went from non-existent to steady and sustainable growth.”

In the future, international student enrollment at the non-degree level is likely to continue to experience peaks and valleys, mirroring international political and economic conditions that are ever changing. But while declining enrollments can be of concern, with thoughtful and proactive management strategies, the outlook for the future need not be.