Jeffrey Gross, Policy Consultant at World Education Services, WES Global Talent Bridge Program

At the national level, the supply of teachers in the United States has remained stable in recent years. At the state and local level, however, school districts have wrestled with long-standing teacher shortages in a number of areas: science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) subjects; career and technical education (CTE); bilingual education; and special education. Schools in low-income and minority neighborhoods in particular often face difficulty recruiting and retaining STEM teachers.1 [1]

Immigrant professionals who’ve earned degrees from abroad are, in many cases, perfectly poised to help address these teacher shortages. How? By stepping into the classroom as educators. The challenge lies in ensuring that their education and experience put them on the fast track to obtaining a U.S. teaching license.

A recent article in Techniques, the journal of the Association for Career & Technical Education, profiles three STEM specialists who were educated overseas:

- “Gebre earned his bachelor of science in chemical and bio-engineering at Addis Ababa University in Ethiopia, going on to work in quality assurance and lab management as well as teaching high school English and physics. After coming to the U.S. as a refugee in 2016, he first worked in sales and is now putting his technical skills to work as a production manager at a dental research and manufacturing company.

- Leila was a family practice doctor in Iran, working in both city hospitals and underserved rural areas. In her eight years in the U.S.—while perfecting her English and gaining citizenship—she’s been a medical translator, a community health educator, and an instructor in a medical assistant program, continuing her commitment to health care despite barriers to becoming relicensed as a physician here.

- William came to the U.S. from Jamaica, where his degree in agricultural engineering and agronomy led to over 12 years of international experience as a project consultant and engineering director in rural development projects, and teaching high school agricultural science and Spanish along the way.” Jeffrey Gross, “Can Immigrant Professionals Help Address CTE Teacher Shortages?” Techniques, 93, no. 8 (2018). This article by the author of the new WES report focuses specifically on pathways into Career and Technical Education (CTE) teaching.2 [3]

“These three industry professionals couldn’t be more different,” the article continues, “but they have two things in common: First, they’re all work-authorized immigrants to the U.S. who gained their education and work experience abroad. Second, they are part of a growing pool of talented and resourceful multicultural professionals with the potential to provide much-needed STEM teaching talent—and a crucial global perspective—in K-12 classrooms.”

The Techniques article draws on research from a recent report [4] produced by WES Global Talent Bridge: Reducing Teacher Shortages in the U.S. Released in November, the report looks at teacher shortages in public schools across the U.S., and the role that internationally educated immigrants and refugee professionals can play in addressing these shortages.

The report focuses on alternative teacher certification initiatives that seek to attract a diverse group of career changers and subject matter experts to the classroom—immigrant professionals among them. The report also offers policy recommendations at the local, state, and federal levels that would help advance such efforts and meet the needs of increasingly diverse schools.

Immigrant Professionals and Alternative Teacher Preparation Programs

Almost every state offers alternative teacher certification options. They now make up nearly one-third of teacher preparation programs nationally, and their number is growing.3 [5] As noted above, these initiatives seek to attract diverse and nontraditional candidates—including industry professionals and paraeducators—and fast-track them into the teaching profession. Many of these candidates have significant experience in STEM and CTE and are also bilingual and bicultural.

Requirements vary by state and program, but most alternative routes to certification require candidates to have at least a bachelor’s degree. On their way to achieving full teacher certification, candidates must typically complete course work in key subject areas and pedagogy, and obtain relevant classroom teaching experience and professional mentoring.

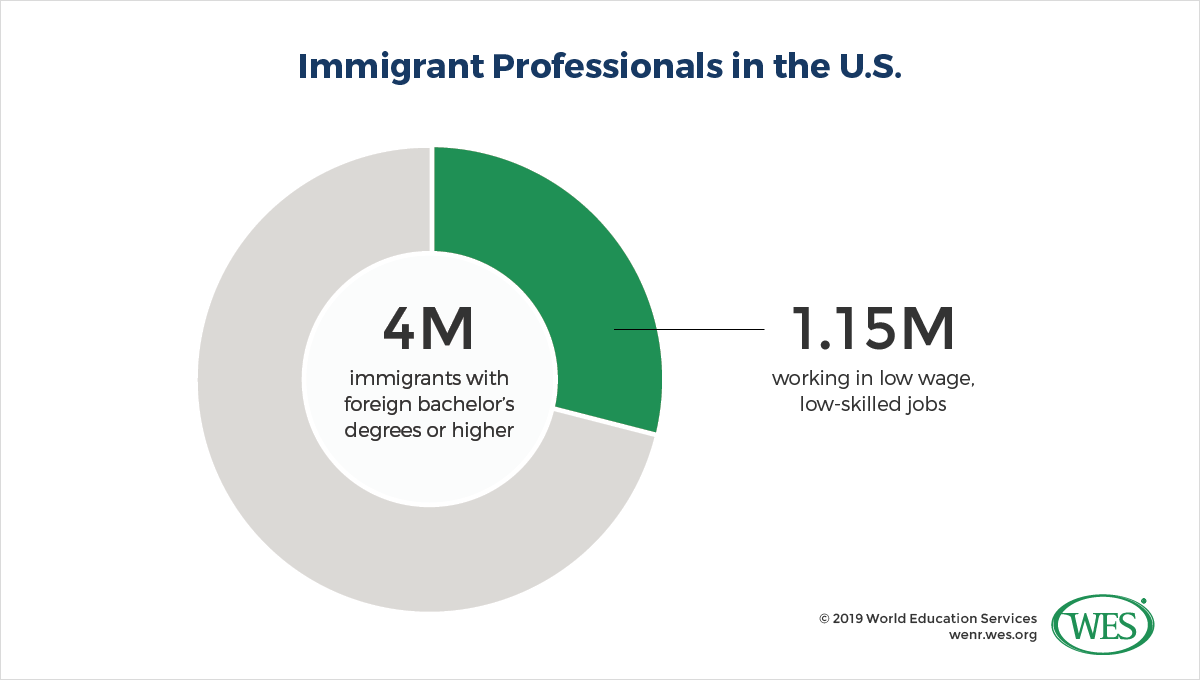

The potential for highly skilled immigrants to address teacher shortages in the U.S. is significant: Of the nearly four million immigrant professionals in the U.S. labor force who have a foreign bachelor’s degree or higher, 29 percent are unemployed or working in low wage or low-skilled jobs.4 [6] This percentage includes more than 260,000 immigrants who hold teaching degrees, 41 percent of whom are unemployed or underemployed.5 [7]

RECOMMENDATIONS

The report closes with recommendations in two areas. First, WES Global Talent Bridge points to program and policy models that can facilitate the entry of more foreign-trained professionals into the nation’s teaching workforce. These include:

- Expanded outreach to foreign-trained immigrants in the context of existing alternative certification programs

- More targeted and fully articulated pathways that meet the unique needs of immigrant professionals

- Policy or regulatory changes to make requirements for education, work experience, and testing more flexible and streamlined for skilled immigrants

Second, the report proposes strategies that local, state, and national education stakeholders can use to leverage the unique assets of immigrant professionals and the opportunity they represent in helping to address urgent teacher shortages in the U.S. These include:

- Convening stakeholders across the K-12 and higher education systems to share perspectives and best practices

- Research and communications that elevate public and policymaker awareness of best practice program models

- Cross-sector collaborations among stakeholder groups to cross-fertilize the field by aligning program and policy strategies, long-term goals, resources, and conceptual frameworks

Across all parts of the educational system, the U.S. needs leadership, collaboration, commitment, and creativity to build bridges to the teaching profession. School districts can play a key role in this process. All school districts, but especially those in immigrant-rich communities, are in a position to creatively leverage programs that tap into the foreign-trained talent in their midst.

The WES report suggests that we are at a tipping point. Many are recognizing the potential contributions skilled immigrants could bring to U.S. classrooms. In a K-12 education system working to address challenges on many fronts, immigrant professionals can become part of a teaching workforce that meets the needs of all students and prepares them for the demands of the 21st century economy.

1. [8] In the 2015–2016 school year, for example, 42 states plus Washington, D.C., reported teacher shortages in mathematics; and 40 states and Washington, D.C., reported teacher shortages in science. See Leib Sutcher, Linda Darling-Hammond, and Desiree Carver-Thomas, A Coming Crisis in Teaching? Teacher Supply, Demand, and Shortages in the U.S. (Palo Alto: Learning Policy Institute, 2016), https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/product-files/A_Coming_Crisis_in_Teaching_REPORT.pdf [9]; and Stephanie Aragon, Teacher Shortages: What We Know (Denver: Education Commission of the States, 2016), https://www.ecs.org/wp-content/uploads/Teacher-Shortages-What-We-Know.pdf [10].

2. [11] Jeffrey Gross, “Can Immigrant Professionals Help Address CTE Teacher Shortages?” Techniques, 93, no. 8 (2018). This article by the author of the new WES report focuses specifically on pathways into Career and Technical Education (CTE) teaching.

3. [12] Office of Postsecondary Education, U.S. Department of Education, Alternative Teacher Preparation Programs. Title II News You Can Use (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education, 2017). https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED576129.pdf [13]. In 2014, 47 states and the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands reported having state-approved alternative routes to a teaching credential.

4. [14] Jeanne Batalova, Michael Fix, and James D. Bachmeir, Untapped Talent: The Costs of Brain Waste among Highly Skilled Immigrants in the United States (Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute, 2016), https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/BrainWaste-FULLREPORT-FINAL.pdf [15]. Based on Migration Policy Institute (MPI) tabulation of U.S. Census Bureau pooled 2009-2013 American Community Survey (ACS) data. In this report, the terms “foreign-trained professional,” “internationally-educated professional,” “immigrant professional,” and “high- skilled immigrant” are used interchangeably to refer to immigrants or refugees who earned bachelor’s or graduate degrees outside of the U.S. More than half (56 percent) of immigrants in the U.S. with a four-year degree or higher obtained their education outside the U.S.; see Batalova, et al., Untapped Talent.

5. [16] MPI, Brain Waste in the U.S. Workforce: Select Labor Force Characteristics of College-Educated Native-Born and Foreign-Born Adults (Washington, D.C.: MPI, 2014), https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/FactSheet_BrainWaste_US-FINAL.pdf [17]. Based on MPI tabulation of U.S. Census Bureau pooled 2010-12 ACS data.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of World Education Services (WES).