Dr. Omolabake Fakunle, Educational Researcher, Moray House School of Education, University of Edinburgh

Over the past two decades, international higher education has expanded rapidly, bringing tremendous benefits to institutions, scholars, and communities around the world. The main benefits to institutions are: recruiting talented students from a global pool and significant financial gains from fee-paying international students. International higher education also enable scholars to develop a wider scope for research and knowledge exchange opportunities. However, the current global political climate, marked by strident nationalist rhetoric, is affecting mobility trends [2] and making receiving countries compete more closely for international students. To attract and retain qualified students, institutions will need to focus on those students’ needs and commit to improving student experiences and outcomes.

Internationalization in Higher Education

Internationalization as an organized system is a distinctly 21st century phenomenon, facilitated as it is by globalization and technological advancement. It is also an emerging area of strategic development.

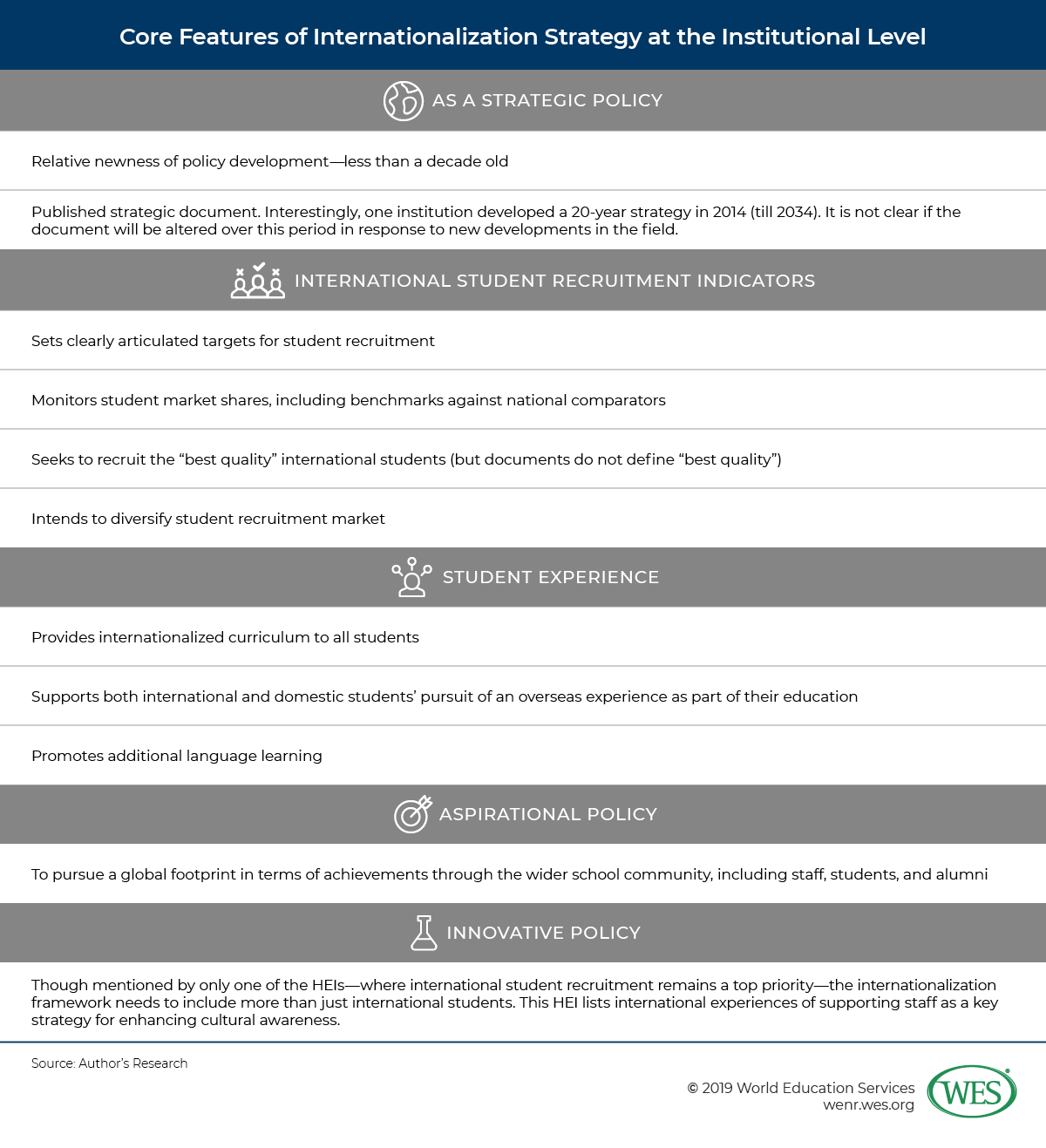

Higher education institutions (HEIs) assert they are ‘international’. Perhaps unsurprisingly, they started developing internationalization strategies within the last decade. These strategies are now so important, it would be strange to find an institution that does not include them in its policies—at least in the Western Hemisphere. These strategies remain a topic of discussion among scholars and other stakeholders for many reasons, one being that “misconceptions of internationalization still prevail [3].”

Internationalization frameworks developed over the last four decades are largely planned from institutional and national viewpoints. However, within the last decade, scholarly discourse has noted the exclusion of academic and administrative staff [4] and students [5] from internationalization frameworks. Despite this growing awareness that there are gaps in existing frameworks, there is scant evidence that institutional strategies have taken into account a need to address those gaps – exposing the crucial role of institutional policy and its direct impact on students and their overall experience.

This article briefly explores internationalization policies at the institutional level. The focus is on five institutions in the United Kingdom, a top destination country (second to the United States) for expatriate students and home to the most international universities in the world [6] in terms of students and staff. These universities—University College London, the University of Manchester, the University of Edinburgh, Coventry University, Kings College London—identified here but anonymized in the discussion of their data, recruited more international students than any other HEIs in the UK in the 2016/17 academic year [7]. Representing only around 3 percent of the UK’s HEIs, they collectively recruited 14 percent (n=61,425) of the country’s international students that year, according to the latest Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) 2018 data [8]. They also represent a range of institutions: They are both old and modern, and are located in different parts of the country—England and Scotland.

These HEIs were selected for two reasons: first, to examine the internationalization focus of such top recruiting institutions; and second, to critically explore whether student voices—that is, the expressed needs of students—are included in their policy documents. Key points across these HEIs are below.

Student Voices in Institutional Discourse

The strategic approach outlined in the policy documents shows that student recruitment remains an overall priority in institutional internationalization discourse. In view of the higher education funding structure in the UK, international student recruitment will likely continue to matter to institutions. One HEI states that around two-thirds of its £263m (USD$334) tuition fee income came from international students in 2013/14 [10].

However, international student voices were deafeningly silent in all the policy documents. Success was measured quantitatively—by increasing the numbers of international students or the diversity of source countries. The similarity in goals and scope of operation suggests that the omission of student voices is the norm. HEIs could draw on student’s experience and viewpoints to develop effective strategies that could enhance the delivery higher education to its beneficiaries.

As mentioned earlier, internationalization strategies at HEIs are a relatively new development, yet omitting student voices from these policies is already problematic. The omission could mean that the strategies don’t address the needs [11] of international students, some authors have argued, and that the economic benefit of recruiting international students is the real goal of such strategies.

Furthermore, even the broad, innovative policy mentioned earlier fails to acknowledge the need to support what is arguably a diverse pool of international candidates—those who might be talented but unable to afford an international education [12]. This support should be in addition to facilitating the overseas experiences of students and staff.

In essence, there is a need to understand the rationale for a study abroad experience. The rationale would provide a framework for assessing the extent to which the study abroad experience matches or aligns with student expectations. However, such qualitative interrogation of rationales is largely missing from the current discourse. For example, the broad, innovative policy does not take into account the distinctions between domestic and international students’ rationales for studying at the institution. Instead, what abounds in the literature are quantitative data in the form of student mobility (to pursue a full degree or credit towards one). From the perspective of the institution, which seeks to increase international student enrollment, quantitative data are measures of successful internationalization.

How Should We Measure Success?

However, the question remains—do quantitative measures (such as the number of international students in an institution) indicate successful internationalization from a student’s perspective? To help answer this question, my doctoral research (completed in 2019) provides an empirically based framework, divided into four “frames,” for understanding student rationales for studying abroad [5]: educational, experiential, aspirational, and economic. Institutions can use this model to form a holistic internationalization strategy that recognizes different stakeholder perspectives, expectations, and roles.

Some aspects of existing strategies align with student rationales. For example, the experiential rationale relates to students seeking an educational, cultural, and social experience abroad. A multinational classroom is important to such students, who seek a truly international learning and social experience. This rationale ties in with the institutional aims of facilitating cultural awareness amongst students and staff. Additionally, it agrees with institutional strategies which seek to diversify source recruitment countries. Keep in mind, however, that a study abroad experience does not necessarily foster intercultural skills and competencies, just the way the presence of international students on a campus does not necessarily promote intercultural encounters.

Students tend to view the international environment as a melting pot of multiculturalism where they can share and learn about different cultures and values. At the same time, understanding that international students want to share their knowledge with other students, domestic and expat, could pave the way for institutions to develop enabling structures that would support this exchange, thus enriching the student experience. However, this is an area where student rationales diverge substantially from institutional policy which focuses on delivering an intercultural experience without the inclusion of input from the students – who bring a wealth of multicultural knowledge. Importantly, what empowers students—and staff—is the intentional development of policies that facilitate student and staff intercultural learning.

Conclusion

Current discourse, evidence from HEIs that recruit some of the largest numbers of international students, and recent research all point to the need to reframe the internationalization process so that the expressed needs of students—student “voices”—are included. To this end, HEIs must explore innovative ways to align both student and institutional rationales for pursuing an international experience. There is a need [13] to pull together expertise and resources to tackle this challenge, especially in view of the contributions of multiple stakeholders to internationalization in an increasingly globalized world.

Dr Omolabake Fakunle is an Educational Researcher and Tutor at Moray House School of Education, University of Edinburgh. Email: [email protected] [14], Twitter: @LabakeFakunle [15], LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/omolabake-fakunle-812b3733 [16]

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of World Education Services (WES).