Stefan Trines, Research Editor, WENR

Introduction: A Tiger Economy Threatened by Climate Change

Bangladesh is a fast-growing, economically dynamic South Asian country. The territory of this Muslim-majority nation is mostly surrounded by India, although Bangladesh also shares a 170 mile-long border with Myanmar. This border region is frequently in the news because of the inflow of some 740,000 Rohingya refugees [2], more than half of them children, fleeing armed conflict and genocide in Myanmar’s Rakhine state. The influx of so many refugees only adds to Bangladesh’s demographic pressures. Bangladesh is the world’s eighth most populous nation and one of the most densely populated countries in the world. About 161 million people [3] live on a territory smaller than the U.S. state of Michigan.

Most of the population lives in a vast river delta adjacent to the Bay of Bengal. These low lying river areas are increasingly polluted and vulnerable to erosion, frequent floods, and tropical storms. According to the Bangladeshi government, a quarter of the country gets inundated by flooding every year while “every 4 to 5 years … there is a severe flood that may cover over 60% of the country and cause loss of life and … damage to infrastructure, housing, agriculture and livelihoods [4].” Scientists predict that these conditions will worsen and trigger a mass exodus since Bangladesh’s delta region will be among the places most affected by climate change. By some estimates, rising sea levels could permanently “submerge almost 20 percent of the country and displace more than 30 million people [5]” while wreaking havoc on local ecosystems [4]. Bangladesh’s population is simultaneously expected to rise to 193 million by 2050 (UN medium variant projection [6]), growing by almost one million people annually.

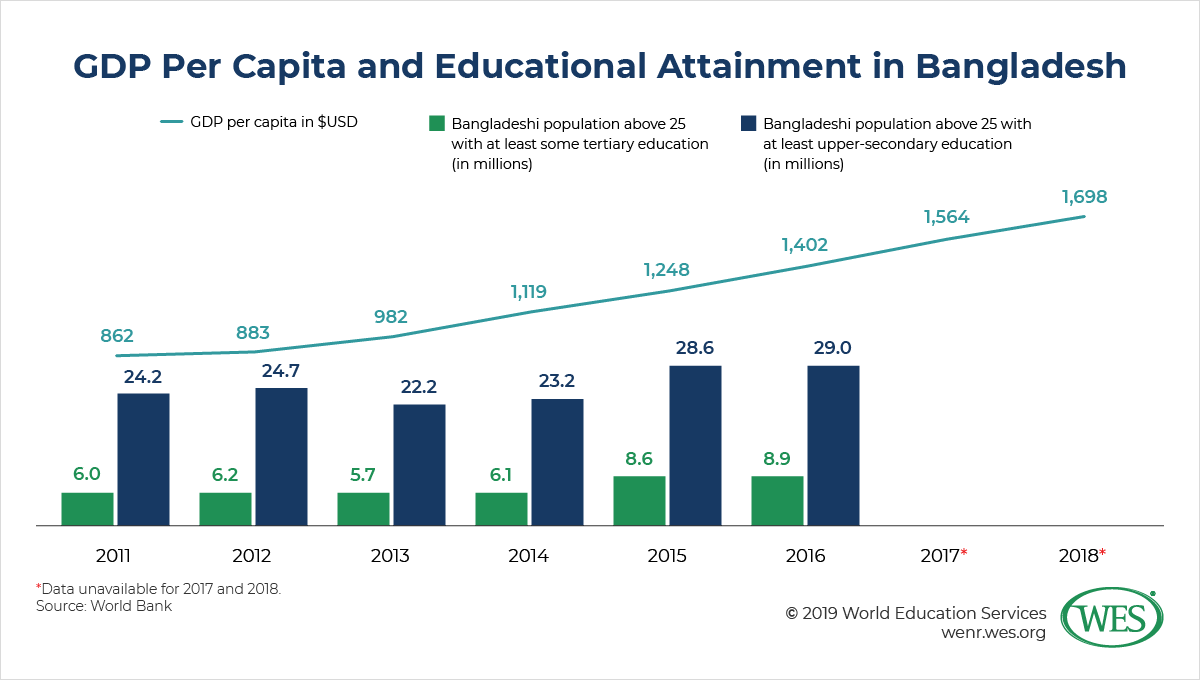

Despite such pressures, Bangladesh’s economy surprised many observers with a remarkably robust performance in recent years. The country’s GDP has been growing by more than 6 percent annually for the past decade, and its economy is predicted to be among the world’s fastest expanding in 2019. Its current growth rate stands at over 7 percent, according to the World Bank [8]. What’s more, economic growth is said to be inclusive with the percentage of the population living in extreme poverty dropping from 44 percent in 1991 to around 15 percent in 2017 [9]. A main driver of the recent growth is Bangladesh’s transformation into a garment manufacturing hub of global scale: The country is now the second-largest exporter of textiles in the world after China. Its clothing industry employs some 20 million people [10] and accounts for more than 80 percent [11] of all Bangladeshi exports.

This development is a remarkable turn of events from the days when Bangladesh, then called East Pakistan, was an impoverished region of the state of Pakistan. After it gained independence in 1971, the country remained one of the world’s least developed countries for decades before it eventually reached the status of a lower middle-income economy in 2015. It now outperforms Pakistan on several economic indicators, and its GDP per capita is expected to be higher than that of India in real terms by 2030 [12]. Reflective of how fast Bangladesh has developed compared with other South Asian countries, its internet penetration rate presently far exceeds that of both India and Pakistan. According to the Bangladesh Telecommunication Regulatory Commission, slightly more than 50 percent of the country’s population had an internet subscription in April 2018 [13]—an astronomical increase over 2010, when merely 3.7 percent [14] of Bangladeshis were online.

Despite economic growth, however, Bangladesh remains marred by immense social problems, such as rapid and uncontrolled urbanization, overcrowding, pollution, inadequate health care, high child mortality rates, gender gaps, land scarcity, and severe urban-rural disparities. Some 24 percent of the population still lives in poverty; more than half that lives in extreme poverty, surviving on less than USD$1.9 a day [15]. Youth unemployment has doubled between 2000 and 2017, and the International Labor Organization recently noted that 27 percent of youths (aged 15 to 24) were not engaged in any form of education, employment, or training in 2018 [16].

This lack of economic opportunity causes more than 400,000 Bangladeshis [17] each year to leave and work as migrant workers overseas, mostly in the Persian Gulf region. In the long term, it also remains to be seen if Bangladesh can sustain economic growth and maintain its leading position in the global garment industry, now that lower cost production countries like Ethiopia [18] are becoming favored destinations of clothing companies.

The Quest to Expand Access: Challenges in Education

As in many other developing countries, the core issue for education policy makers in Bangladesh has been to increase access to education and boost educational attainment rates. Tremendous progress has been made in these areas over the past decades. The net enrollment ratio in elementary education, for instance, now stands at more than 90 percent compared with 60 percent in the mid-1980s (per UNESCO data [19]). The adult literacy rate, likewise, surged from 35 percent in 1991 to 73 percent [20] in 2017. To further increase participation and improve learning outcomes, the Bangladeshi government in 2010 adopted an ambitious new national education policy [21] that introduced one year of compulsory preschool education and extended the length of compulsory education from grade five to grade eight. Other changes include the introduction of a common elementary core curriculum and national examinations at the end of grades five and eight.

However, while the government has recently built thousands of schools, notably in remote rural areas, and poured considerable resources into improving education, implementation of many of the reforms remains a work in progress hampered by funding problems and inadequate school infrastructure. Many classrooms are overcrowded, and teachers are often poorly trained. Dropout rates are high with nearly 20 percent of pupils not completing elementary school in 2016 [23]. At the lower-secondary level, the dropout rate stood at 38 percent in 2017 with fully 42 percent [24] of girls leaving school before completing grade 10, due to factors like poverty and child marriage. Teacher-to-student ratios, meanwhile, remain well above the official target ratio of 30:1 (42:1 in secondary schools in 2016 [24]).

Private Tutoring in Bangladesh

The introduction of national examinations at the elementary level has been roundly criticized for feeding Bangladesh’s mushrooming private tutoring industry and placing children from low-income households at a disadvantage since their parents are unable to afford such services. Private tutoring is a lucrative and growing business in Bangladesh. More than half of all secondary students in the country use private tutors, according to UNESCO. It is so common that it has been dubbed a “shadow education system [25].” According to surveys, payments for private coaching are the single largest expenditure item on education for Bangladeshis, making up 29 percent [26] of all education-related costs borne by private households. Government attempts to outlaw private tutoring and enforce tuition caps have thus far failed. Not only do parents continue to solicit tutoring services, but schoolteachers sometimes also extort students, pressuring them into paying for after-school tutoring with the threat of low grades or other punitive measures [26].

In higher education, challenges are omnipresent as well. Crucially, Bangladesh has severe capacity shortages reflected in a low tertiary gross enrollment ratio (GER). Even though the country’s tertiary GER has doubled over the past decade, it stood at merely 17.6 percent in 2017. While that’s seven percentage points higher than in Pakistan, it’s a low percentage by international standards and trails India’s tertiary GER by a full 10 percentage points (UNESCO data [19]). Seats at Bangladesh’s top tier of competitive public universities are so scarce that some 95 percent of upper-secondary school graduates are unable to attend these institutions; 17 applicants [27] competed over one public university seat in 2015.

Those that are admitted face overcrowded classrooms because of a shortage of lecturers [28]. University curricula, meanwhile, are said to be of limited relevance to the needs of industry. In 2017, 16 percent of university graduates were unemployed compared with 7 percent of secondary school graduates. Many Bangladeshi companies reportedly prefer to hire better educated foreign graduates [29].

The inability of public institutions to accommodate the surging demand for higher education among swelling cohorts of high school graduates has helped create a mushrooming private sector—the number of private universities in Bangladesh has surged to 103 since the country first allowed private higher education in 1992. While some of these institutions are top quality, elite institutions, others are lackluster, so that the higher education system is characterized by wide disparities.

The University Grants Commission (UGC), Bangladesh’s quality assurance body in higher education, had to crack down on several private universities in recent years because they offered unauthorized certificate programs [30] and ran illegal branch campuses [31]. In 2016, there were reports that many newly established private medical colleges lacked adequate resources and relied primarily on part-time teaching staff—a disconcerting trend resulting in a freeze of approvals of new colleges [32]. Despite such measures, however, a number of unauthorized higher education institutions (HEIs) continue to operate illegally [33] in the country.

On the Move: Outbound Student Mobility

Outbound student flows from Bangladesh have surged in recent years, making it an increasingly dynamic source country of international students, akin to other South Asian countries like India and Nepal. The number of Bangladeshi nationals enrolled in degree programs abroad almost quadrupled within 12 years, from 15,000 in 2005 to 56,000 in 2017, according to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) [19].

While observers like the British Council foresee an overall slowing of global international student flows in the near future, Bangladesh is expected to be among a select group of countries that will sustain increases in outbound student mobility [34] for years to come.

Among the factors driving this swelling outflow are the expansion of Bangladesh’s college-age population, capacity shortages in higher education, and the emergence of a growing middle class able to afford an overseas education, notably in major urban centers like Dhaka and Chittagong. The Boston Consulting Group has predicted [35] that the number of middle income and affluent Bangladeshis will grow at a rate of more than 10 percent annually and increase from 12 million in 2015 to 34 million by 2025.

The low quality of life and poor education in Bangladesh, as well as the lack of employment opportunities, cause growing numbers of youngsters from these newly prosperous households to go overseas, thereby exacerbating the country’s brain drain. Most international students come from wealthier households and were educated at English-medium schools [36]. Many do not return after completing their studies. As one Bangladeshi professor told the Dhaka Tribune newspaper, “jobs and investments are not generating nearly the amount of money needed … for a standard of living, the young do not see a future for themselves in Bangladesh. Many are frustrated over the hostage situation created by poverty along with political unrest and no industrial and agricultural development, which has worsened their perception of the country [37].”

While international degree-seeking students from Bangladesh went mainly to the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, and neighboring India in the early 2000s, Malaysia has emerged as the most popular study destination by far in recent years. It presently accounts for about 50 percent of all Bangladeshi enrollments in degree programs abroad after the number of such students spiked by 1,500 percent, going from 1,722 students in 2010 to 28,456 in 2017 (per UNESCO data [19]).

Malaysia is attractive to Bangladeshi students because it’s a multicultural, Muslim-majority country that is nearby. It’s also a comparatively low-cost study destination, and international students in Malaysia are permitted to work part time. Programs are usually taught in English, and Western education is also easily accessible via branch campuses of U.S., British, and Australian universities. There’s also a sizable Bangladeshi community in the country, a result of the inflow of migrant workers. Unfortunately, there are reports [38] of Bangladeshi students being scammed [39] and trafficked by criminals and unscrupulous recruitment agents. In 2017, Singaporean media reported [40] that thousands of Bangladeshis had been lured into Malaysia to study at fake universities only to be exploited as undocumented workers [41].

In the U.S., Bangladesh is among the top 25 sending countries of international students, primarily because of Bangladeshi enrollments in graduate programs. There were 6,492 Bangladeshi degree-seeking students in the country in 2017, according to UNESCO [42], making the U.S. the second most popular destination and putting it ahead of Australia (4,986 students), the U.K. (3,116 students), and Canada (2,028 students).

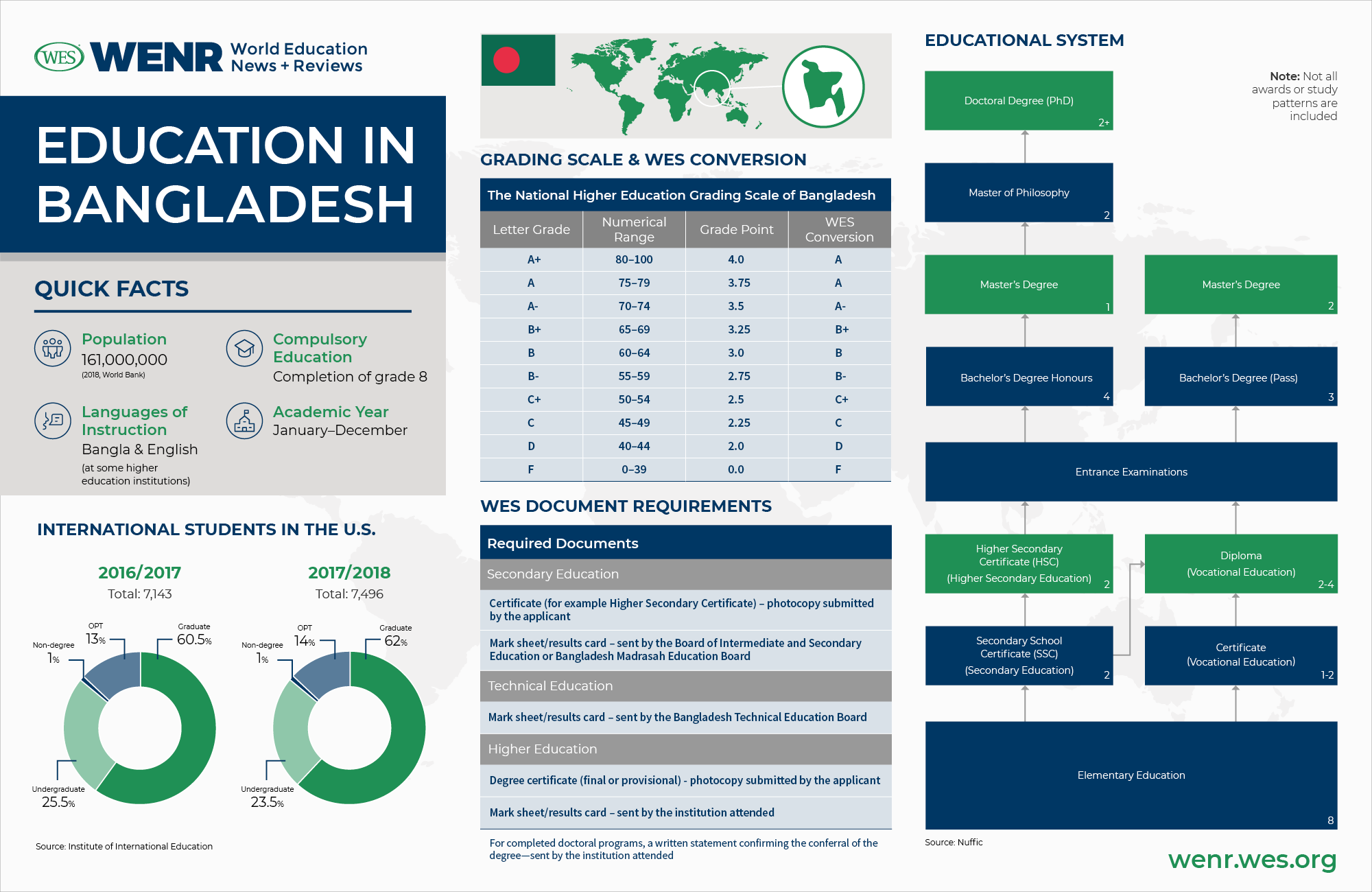

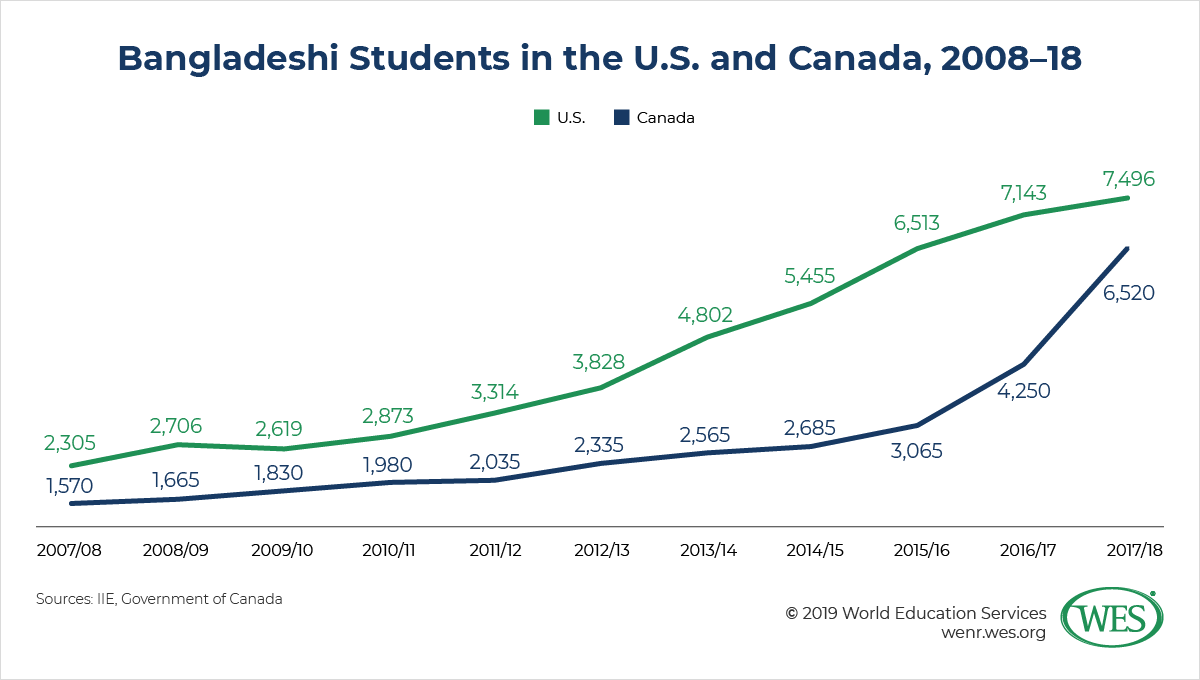

Per Open Doors data [43] of the Institute of International Education, which also include non-degree students, there were 7,496 Bangladeshi students in the U.S. in the 2017/18 academic year—an increase of 4.9 percent over 2016/17, and nearly twice as many students as in 2012/13. Fully 62 percent of them studied at the graduate level, while 24 percent were enrolled in undergraduate programs, less than 1 percent in non-degree programs, and 14 percent pursued Optional Practical Training. The most common majors among Bangladeshi students are engineering, math/computer science, and physical/life sciences [44].

As in the U.S., the number of students from Bangladesh has grown rapidly in neighboring Canada as well. Although the number of degree-seeking students as reported by UNESCO is still relatively small, Canadian government statistics [45] show that the total number of Bangladeshi students, including non-degree and language training students, has tripled within just six years, from 2,035 in 2012 to 6,520 in 2018.1 [46]

Inbound Student Mobility

Given that Bangladesh is a poor country without world-class universities, it’s not a major international study destination. Concrete information on the total number of international students in the country is difficult to find, but data from 57 universities published by the government [48] showed that there were 1,402 international students enrolled at these institutions, most of them from African and South Asian countries. Other numbers, released by the UGC, put the number of international students enrolled at 53 universities at 2,282 in 2016 [49]. The top sending countries include Somalia, Nigeria, and Nepal. International students from Somalia interviewed [50] by the Dhaka Tribune stated that they chose Bangladesh for their studies because the country has a better education system than Somalia and is relatively inexpensive compared with Western destinations.

Most students study at private institutions, where enrollments have recently [49] been on an upward trajectory. The private University of Science and Technology Chittagong, for instance, attracts large numbers of international medical students from other South Asian countries like India, Sri Lanka, Bhutan, and Maldives with its low-cost medical programs.2 [51] The UGC seeks to bring greater numbers of international students to Bangladesh, and has recently initiated some modest marketing activities [50].

In Brief: The Education System of Bangladesh

As in the other South Asian countries that were formerly part of British India, modern education in Bangladesh has been markedly shaped by Great Britain. To train local administrators for its colony, the British in the late 18th century established the first Western-style HEIs. In the early 19th century, English was made a compulsory high school subject and a requirement for admission to higher education [52].

When British rule over the Indian subcontinent eventually came to an end in 1947, present-day Bangladesh was part of the newly independent Dominion of Pakistan as the province of East Pakistan. The new government chose Urdu, a language predominantly spoken in West Pakistan (present-day Pakistan), as the national language and language of instruction in public schools. It also incorporated Islamic education into the public school system [52]. The education system was highly elitist and failed to benefit large parts of society. According to a 1961 census, the literacy rate stood at 21.5 percent in East Pakistan and 16.3 percent [53] in West Pakistan.

It was not before 1956 that the Bengali language (Bangla), spoken by most people in East Pakistan, was added as one of Pakistan’s national languages. Language discrimination, wealth disparities, and the political marginalization of East Pakistan were among the sources of conflict giving rise to the Bangladeshi independence movement, which culminated in the brutal Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971.

After independence, the democratically elected government of Prime Minister Sheikh Mujibur Rahman introduced a secular education system using Bangla as the language of instruction. However, the role of Islam in Bangladesh has been contested ever since. Successive military governments eroded secularism and made Islam the state religion of Bangladesh in the 1980s.3 [54]

Supreme court rulings rendered after the re-democratization of Bangladesh in the 1990s have reintroduced and strengthened secularism [55], but Islamic conservatism is nevertheless on the rise in contemporary Bangladesh [56]. Approximately 90 percent of Bangladeshis are Sunni Muslims, followed by Hindus (9.5 percent) and small numbers of Christians, Buddhists, and members of other faiths.

Administration of the Education System

Formerly called the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, Bangladesh is a unitary state that consists of eight administrative divisions (bibhag): Barisal, Chittagong, Dhaka, Khulna, Mymensingh, Rajshahi, Sylhet, and Rangpur. Education is centrally steered by the Ministry of Education (MOE) in Dhaka. It oversees a variety of agencies, including the Directorate of Secondary and Higher Education, responsible for secondary and higher education, the Directorate of Technical Education, and the formally autonomous National Curriculum and Textbook Board.

In addition, there’s a dedicated ministry for elementary education and non-formal education programs for out-of-school children and adults called the Ministry of Primary and Mass Education [57]. Its directives are implemented by the Directorate of Primary Education and the Directorate of Non-formal Education, which have hundreds of local field offices throughout the country [58].

All of Bangladesh’s administrative divisions have their own Boards of Intermediate and Secondary Education (BISE [59]) which develop, organize, and supervise the Secondary School Certificate and Higher Secondary (School) Certificate examinations. There’s a separate nationwide board for religious Muslim schools or madrasahs, the Madrasah Education Board, as well as a Technical Education Board that develops curricula and administers graduation examinations in technical and vocational education (TVET).

The main oversight and quality assurance body in higher education is the UGC, an autonomous institution under the MOE. Like the University Grants Commissions in India and Pakistan, the Bangladeshi UGC is modeled after the now defunct British University Grants Committee. It is an agency that essentially disburses government funds (grants) to public universities in exchange for their compliance with set quality criteria. In addition, the UGC acts as a coordinating body between universities and is tasked with monitoring and regulating private universities [60].

In 2017, Bangladesh’s parliament passed the Accreditation Council Act to establish an additional quality assurance body in higher education [61]. However, the accreditation council was not yet fully operational as of this writing, even though its establishment has long been planned.

Academic Calendar and Language of Instruction

The academic year in Bangladesh runs from January to December in both the school system and higher education. Schoolchildren attend classes for six days a week (Saturday-Thursday) with Friday being a day off, since it’s a Muslim day of religious observance. Public universities and many private universities use semester systems, but trimester systems are still common at private HEIs. The UGC in 2017 directed all private universities to use semester systems [62].

The languages of instruction are Bangla in the school system and Bangla and English in higher education; most private universities teach solely in English.

Elementary Education

Education in Bangladesh is compulsory until the end of grade eight. Until recently, the system was divided into five years of elementary education, three years of lower-secondary education and four years of upper-secondary education. However, the latest 2010 education policy [21] introduced a unified, mandatory elementary school cycle of eight years, followed by four years of secondary education, beginning in 2011.

Children must enter elementary education at the age of six. According to the new education policy, they are also expected to have previously attended at least one year of preschool at the age of five or younger. As a result of the change and other factors, the pre-elementary GER surged from 11 percent in 2009 to 40 percent in 2017 [63], according to the World Bank. Most preschool education is provided by private institutions, mostly NGOs like BRAC [64] and others, as well as by mosques, community organizations, and centers attached to elementary schools. Until recently there was little articulation and standardization in this sector, but now the National Curriculum and Textbook Board has developed a pre-elementary curriculum [65] to homogenize preschool education.

Elementary education is provided free of charge at public schools and open to all children at the age of six. As mentioned above, enrollment ratios have increased markedly over the years, but participation in elementary education remains far from universal, particularly in rural regions where schools may be in poor shape, difficult to reach, and children may drop out because they must help with farming. Elementary education is provided by government schools, authorized private institutions, community schools, and special needs schools for basic education in underserved areas [58].

The elementary school curriculum teaches Bangla, Bangladesh studies, English, mathematics, moral science, the social environment, and the natural environment as compulsory subjects. Vocational subjects may be introduced after grade six. According to the national education policy, assessment and promotion in grades one and two are based on continual assessment, while quarterly, semi-annual, and year-end examinations are introduced in grade three [21]. Examination boards of the individual Bangladeshi divisions administer external exams in seven subjects to students who have completed grade eight. In big cities, there may also be district-level examinations at the end of grade five [21]. Upon successful completion of grade eight and passing the final exam, pupils are awarded the Junior School Examination Certificate (JSC). About 2.7 million pupils [66] sat for the JSC examinations in 2018. The pass rate was 86 percent [67].

Secondary Education

While close to 80 percent of elementary students were enrolled in public institutions in 2017, this ratio is reversed in secondary and upper-secondary education, where the percentage of private enrollments stood at fully 97 percent and 91 percent, respectively, as per UNESCO statistics [19]. While that’s one of the highest such ratios in the world, it needs to be noted that these schools are not truly private—their facilities, equipment, and teaching materials are provided by the government, which also pays a large part of the teachers’ salaries [58].

Unlike in elementary education, however, pupils in secondary schools are required to pay tuition fees, which have been rising sharply in recent years [68]. There are additional fees for examinations, and many parents also pay substantial sums for private tutoring [26]. To ease monetary barriers to school enrollment, the Bangladeshi government in 2016 capped tuition fee increases [69] at private schools and provides stipends [70] and tuition subsidies, mostly to girls in rural regions.

In addition to Bangladeshi schools, there’s a growing number [71] of international schools that teach foreign curricula, the British General Certificate of Education curriculum being the most popular. The tuition fees at these schools reportedly averaged USD$5,200 [72] in 2017, so that these schools are accessible to primarily wealthy urban elites. The average per capita income in Bangladesh was USD$1,466 in 2016 [73].

There are also some 20,000 madrasahs that enroll close to four million students at different levels of education. The education provided by these institutions is described in further detail below.

While participation in secondary education has grown strongly over the past decade, attrition rates in Bangladesh are high, particularly among girls, many of whom drop out of school because they marry early or lack the same parental support for education as boys. Whereas the GER in lower-secondary education stood at in 87 percent in 2017, it dropped sharply to 53 percent in upper-secondary education (as per UNESCO [19] data). According to Bangladeshi government statistics, 38 percent [74] of secondary students dropped out in 2016, 42 percent of them females and 34 percent males.

Secondary education is divided into a two-year lower-secondary phase (grades nine and ten) and a two-year upper secondary phase, called higher secondary (grades 11 and 12). Students can study in either a general stream, a religious stream (madrasah), or a technical stream. Each stream offers options for further curricular specializations. General programs, for instance, are offered in business, humanities, and science tracks. All programs have a general academic core curriculum that includes Bangla, Bangladesh studies, English, mathematics, and information technology.

Admission to grade nine requires a minimum grade point average in the Junior School Examination, but admission in the higher secondary phase is competitive. Students need high grades to be accepted to desirable higher secondary institutions [75], enrollment in which, in turn, helps in the competition over scarce university seats. These institutions are called intermediate colleges and can be stand-alone institutions or colleges attached to HEIs.

The Boards of Intermediate and Secondary Education—the madrasah and the technical examination board—administer two external examinations at the end of each phase, each year. In the general and technical education streams, they are called the Secondary School Certificate (SSC) examination and the Higher Secondary Certificate (HSC) examination. A passing score on the SSC exam is required to progress into higher secondary education.

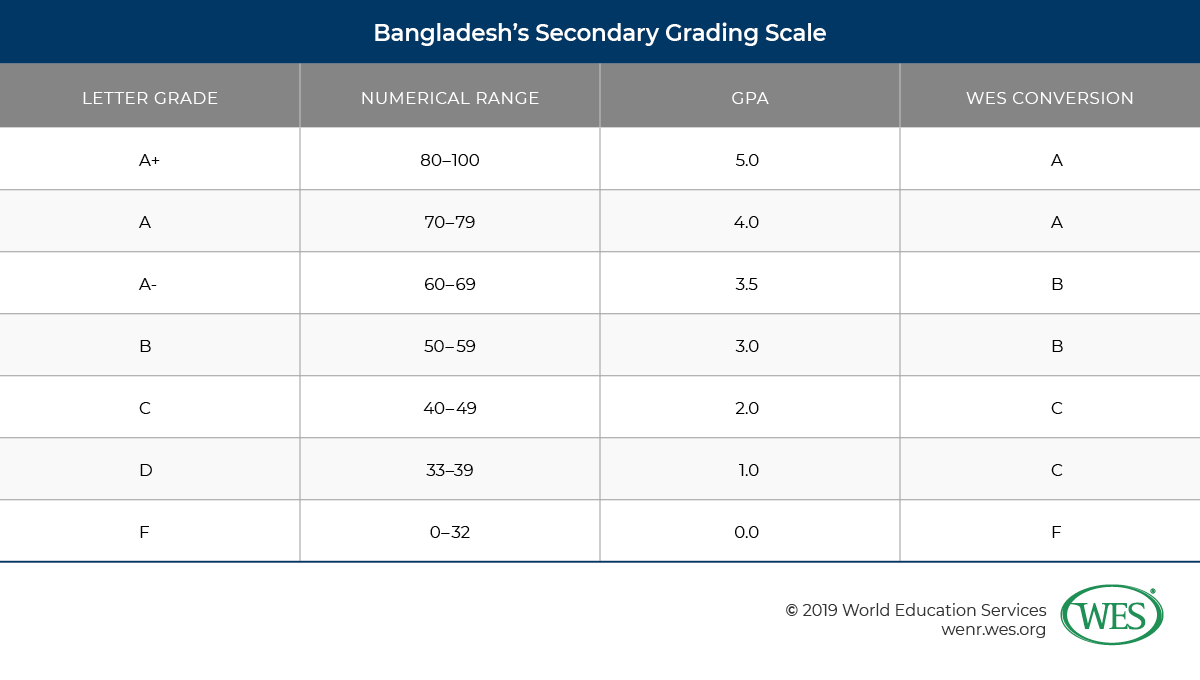

The final HSC exam includes Bangla, English, and information and computer technology as compulsory subjects in addition to one elective. Examination results used to be graded on a 0–100 percentage scale but are now expressed as a grade point average on a scale of 0 to 5 with a GPA of 1.0 being the minimum passing grade. Independent (private) candidates can sit for the examination three years after passing the SSC exam without enrolling in an intermediate college. More than 1.3 million students took the HSC exam in 2018, of which merely 29,262 achieved the highest possible GPA of 5 [76]. The overall pass rate was 67 percent [76]. Examination results are usually announced by the prime minister and can be verified on a website [77] maintained by the MOE.

Madrasah Education

Bangladesh has a large and thriving system of religious schools. Originally dating back to pre-colonial times, these madrasahs exist today either as independent schools mostly devoted to Islamic study (Qawmi madrasahs), or as state-regulated institutions that teach the standard school curriculum in addition to religious studies (Alia madrasahs). The latter receive government funding and are regulated by the Bangladesh Madrasah Education Board (or Alia Madrasah Education Board). They may provide elementary education (Ebtadayee), secondary education (Dhakil), or higher secondary education (Alim).

At the end of grades 10 and 12, the madrasah board holds Dhakil and Alim examinations that are recognized as the equivalent of the SSC and HSC exams in Bangladesh. The workload at Alia madrasahs can be taxing for students [79], since they must study the Quran, the teachings of the prophet Muhammad (hadith), Islamic laws, and Arabic in addition to the mandatory general curriculum. The curriculum usually comprises 60 percent general studies and 40 percent Islamic studies.

Qawmi madrasahs, on the other hand, may be affiliated with one of several religious education boards, such as the Bangladesh Qawmi Madrasah Education Board (Befaqul Madarisil Arabia Bangladesh), which offers a curriculum focusing mainly on religious studies and Arabic, Persian, and Urdu languages. However, board affiliation is not mandatory, and most Qawmi qualifications are presently not recognized by the Bangladeshi government. Qawmi curricula usually don’t include subjects like science, mathematics, and social sciences.

As per the Bangladesh Bureau of Educational Information and Statistics, there were 13,902 Qawmi madrasahs [80] in Bangladesh in 2015, enrolling about 1.4 million students, predominantly males. For comparison, there were 9,319 Alia madrasahs [81] with 2.4 million students, according to the bureau. The number of madrasahs and the number of students they enroll has grown rapidly in recent years; they now enroll up to a third [82] of all school attendees in Bangladesh. Aside from growing religiosity in Bangladesh, lower costs of education [82] and lower admission standards at some schools are part of the growing appeal of religious schools.

Some madrasahs also provide post-secondary education in Islamic studies. Approved Alia madrasas can offer bachelor’s (Fazil) and master’s level (Kamil) qualifications. Until recently, this type of education was overseen by the Islamic University, a long-standing public institution, but to modernize this sector of education, the Bangladeshi government in 2013 [83] shifted oversight to the newly created Islamic Arabic University [84] (IAU), also a government-funded institution. The IAU now approves post-secondary madrasahs and develops, supervises, and examines their programs and awards the final qualifications. The degree structure formerly included a two-year pass or three-year honors Fazil degree, followed by a two-year Kamil degree (2+2 or 3+2), but Fazil programs are now mostly offered as four-year honors programs followed by a one-year Kamil program (4+1 [85]).

In another change, the government in 2017 decided to recognize postgraduate qualifications awarded by Qawmi madrasahs (Dawra) as equivalent to a university master’s degree in Islamic studies [86]. There have been debates in recent years as to whether the government should officially recognize other Qawmi qualifications as well. However, the Qawmi education boards rejected such deliberations over fears that their schools would become state regulated and less independent.

Technical and Vocational Education (TVET)

Aside from vocational specializations within the general secondary track and basic vocational skills certificate programs offered by technical schools and training centers after elementary education, there are several TVET programs offered by polytechnic institutes that students can enter after the SSC examinations in grade 10. Most of these are formal diploma programs between two and four years in length offered in disciplines like engineering, marine technology, nursing, allied health fields, agriculture, or hospitality. While some programs fall under the auspices of institutions like the Bangladesh Nursing and Midwifery Council, the Bangladesh Technical Education Board (BTEB) is the apex regulatory authority in this sector. It approves schools, develops curricula, administers final examinations, and awards the final diplomas and certificates.

Diploma programs are applied in nature with few if any general education requirements. Some may include industrial internships. They can be entered based on either the SSC or Dakhil examination certificate, but admission is competitive—in 2018, for instance, candidates needed a minimum SSC GPA of 3.5 [87], including a GPA of 3.0 in mathematics, for admission into Diploma in Engineering and Diploma in Tourism and Hospitality programs. Holders of the HSC may in some instances be granted advanced placement if they continue to enroll in technical diploma programs. As in general secondary education, the clear majority of TVET providers are private. Public institutions enroll only a minority of students [88].

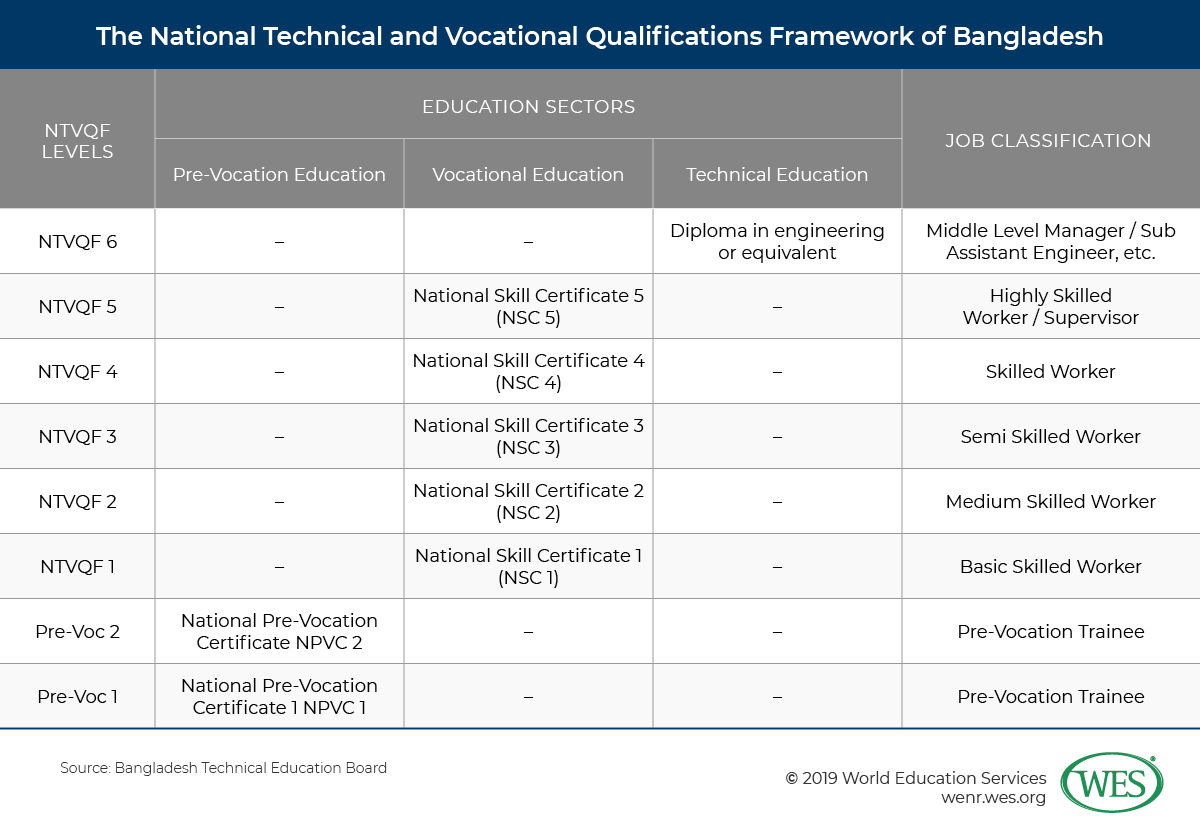

Secondary-level TVET programs are much less popular than general programs—fewer than 9 percent of all upper-secondary students were enrolled in vocational programs in 2017, according to UNESCO [19]. TVET tends to be viewed as second-class education [89] in Bangladesh for several reasons: poorly educated teachers at TVET institutions, funding shortages, and poor employment prospects [88] for graduates. To improve this situation, the government recently initiated several reforms to create a more demand-based system in greater collaboration with industry. It established a Competency Based Training Curriculum Framework [90] under the auspices of BTEB, featuring more clearly defined learning outcomes and competency standards at different levels. It introduced a new National Technical and Vocational Qualifications Framework that defines and categorizes vocational qualifications into six levels, from pre-vocational certificates to national skills certificates and technical diploma-level qualifications, as shown below.

Admission to Higher Education

University seats are a scarce commodity in Bangladesh, especially at quality institutions—in 2017, there were 801,711 potential students who had passed the HSC exams, but fewer than 50,000 [92] available seats in the top tier of competitive public universities. However, larger numbers of spaces are available at the less reputable and non-competitive National University, as well as in open distance education.

Admission criteria differ by institution and faculty, but entrance examinations that are often hard to pass are a common requirement at competitive institutions in addition to set minimum GPAs in the HSC/Alim exams. There may also be minimum grade cutoffs in specific subjects (for example, high grades in mathematics for science programs). Science and engineering programs are generally harder to get into than programs in the social sciences and humanities. All public HEIs are required to use centralized entrance examinations in Bangla, English, and major-specific subjects, according to the current national education policy [21].

Holders of 10+4 Diplomas in Engineering and similar credentials may also be admitted and might be granted some course exemptions. Admission into private universities tends to be far less difficult than into the highly selective public universities, but private universities offer only a limited range of degree programs and are often prohibitively expensive. The average semester fees at private HEIs ranged from USD$470 to USD$946 in 2015 [93].

Higher Education Institutions

As in neighboring India, Bangladesh’s higher education system features a limited number of degree-granting universities, but it does have many smaller affiliated teaching institutions called colleges. The most recent MOE statistics number 3,196 colleges [94], most of them affiliated with Bangladesh’s National University (NU), the country’s dedicated affiliating university. Founded in 1992 to expand capacity in higher education, NU today is Bangladesh’s largest higher education network, enrolling 2.8 million students in 2,300 predominantly private colleges across Bangladesh, according to the institution’s website [95]. That means that colleges affiliated with NU enroll the clear majority of Bangladeshi tertiary students, although it should be mentioned that many colleges also offer upper-secondary HSC programs.

NU may grant affiliation to colleges if they have been in operation for at least three years and satisfy certain conditions, such as adequate facilities and teaching staff [96]. The university prescribes the admission requirements, program curricula, and criteria for teacher recruitment. It conducts examinations and awards the final degrees.

However, not all NU-affiliated colleges teach the full range of degree programs; they most commonly offer three-year bachelor programs (pass degrees) rather than four-year honors programs and they usually don’t teach programs in professional disciplines or doctoral programs. Colleges are much smaller than universities and often have lower tuition fees than private universities, so that many of their students come from lower income households.

Compared with universities, colleges tend to have a poor reputation in Bangladesh. The quality of education provided by these mostly private institutions is said to be lacking because of “accountability and monitoring mechanisms [97] [that] are weak and ineffective,” among other factors. (For further information on this topic, see this [97] informative World Bank study on NU and affiliated colleges.)

Aside from NU, there are an additional 44 public universities [98], as well as 103 UGC-approved private universities [99] in Bangladesh.4 [100] Most public universities are “general” multi-faculty universities offering a broad range of study programs, but there are also a number of specialized universities in fields like agriculture, health care, Islamic studies, medicine, textile engineering, or women’s studies. Other public HEIs include the Bangladesh Military Academy and the National Defense College.

Some of the largest, oldest, and most reputable public research universities are the University of Dhaka, the Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology, and the University of Rajshahi. However, while these universities have the highest research output [101] in Bangladesh, their research contributions are minor by international standards, and Bangladeshi HEIs, public or private, are not well represented in global rankings. While there aren’t any Bangladeshi HEIs included in the Times Higher Education or Shanghai rankings, the University of Dhaka and the Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology are ranked in the 801 to 1000 range in the current QS ranking [102].

Worthy of mention is also the Bangladesh Open University (BOU), a public university and one of the world’s largest mega-universities with more than 500,000 students [103] enrolled. Like NU, BOU was established in 1992 to widen access to higher education. BOU [104]offers formal diploma, bachelor’s, and master’s programs, as well as non-formal programs via distance education on audiocassettes, radio broadcasts, television broadcasts, and the internet. BOU plans to deliver all its programs online in the near future [105]. As the only distance education provider in Bangladesh, the open university plays a significant role in providing educational opportunities for underserved populations in rural areas.

Private Universities

Another result of the shortage of university seats is the rapid growth of the private university sector following the enactment of Bangladesh’s Private University Act. The country’s first private university, North South University, was established in 1992. While most private universities started out as narrowly specialized institutions, particularly in business fields, several of them are now multi-disciplinary institutions. That said, they are mostly smaller institutions clustered in Dhaka and Chittagong.

Private universities are legally required to function as non-profit institutions, but some are said to operate as de facto for-profit ventures [106]. Except for some top institutions like BRAC University, most were not engaged in substantial research activities until recently [107]. Unlike public universities, private universities are not allowed to award higher-level master’s degrees (Master of Philosophy) or doctoral degrees. Almost a third of Bangladesh’s tertiary students are currently enrolled in private HEIs, as per UNESCO data [19].

A recent 2019 ranking [108] of private universities by the Dhaka Tribune and Bangla Tribune ranked North South University, BRAC University, and East West University as the top three private HEIs in the country. But aside from such top institutions, observers have questioned the quality of education at private Bangladeshi universities. As public administration scholars Mobasser Monem and Hasan Muhammad Baniamin have noted [109], for instance, many private universities “have no proper campus and are located in rented facilities and run by part-time teachers.… The major impediments of the private universities include: non-compliance with the statutory requirements, absence of consistent admission and examination policies, non-transparent financial management, lack of adequate number of full-time faculty, lack of proper infrastructure, inadequate laboratory and library facilities, absence of co-curricular and extra-curricular activities and a commercial bias in decision making.”

There have also been reports of financial irregularities and corruption in the approval processes at private universities [110]. On the other hand, private university graduates are said to have higher employment prospects than their public university peers, because the former are taught more industry-relevant curricula [111].

In addition to public and private universities, the UGC granted recognition to three universities it categorizes as “international universities”: The Asian University for Women, the Islamic University of Technology, Gazipur, and South Asian University. These institutions are run by transnational organizations like the Organization of Islamic Cooperation, rather than established under the Private University Act.

It’s been debated recently whether the government should allow foreign universities to open branch campuses in Bangladesh to build capacity. Legislation developed in 2014 [112] technically enabled foreign providers to operate [113] in the country. However, the Ministry of Education in 2016 reversed course and blocked foreign universities from opening shop in Bangladesh [114]. Concerned about competition, private universities strongly oppose the introduction of foreign branch campuses [113].

Quality Assurance

Given the rapid growth of Bangladesh’s higher education system, quality assurance has become an increasingly pressing issue in recent years. Public universities are established by an act of parliament based on the recommendations of the UGC, a statutory government body created in 1973. The UGC is also tasked with ensuring the “academic, administrative and financial discipline” of public universities through “continuous monitoring and supervision,” and to “approve new faculties, departments, institutes and personnel,” as well as “to prevent corruption and irregularities [115].”

Since the enactment of the Private University Act, 2010, private universities are overseen by the UGC as well. The UGC reviews all applications to establish new private universities and programs on behalf of the MOE. Its Private University Division conducts site inspections, approves curricula, and sets guidelines for admissions standards, grading systems [115], and the hiring of faculty. A directory of approved universities and programs can be found on the UGC website.

The UGC’s more recent efforts to improve quality include an initiative to fund the establishment of internal “Institutional Quality Assurance Cells [116]” at public and private universities enrolling more than 1,000 students. The initiative is part of Bangladesh’s Higher Education Quality Enhancement Project (HEQEP [117]), launched in 2009 and implemented by the UGC. The project seeks to foster cooperation between universities, modernize higher education, and expand capacity and research activities. A web-based Higher Education Management Information System will be used to collect and store data to monitor and evaluate the performance of universities and the higher education sector [118] at large.

In 2017, Bangladesh’s parliament also passed legislation to create an independent accreditation council. The plan is to have the council accredit universities, public and private, as well as individual study programs, for periods of five years following an initial interim accreditation period of one year. The first chairman of the council was appointed in August 2018 [61], but the council doesn’t appear to be operational as of this writing. There’s already an independent Board of Accreditation for Engineering and Technical Education [119] (BAETE) that accredits degree programs in these fields under the auspices of the Institution of Engineers, Bangladesh. BAETE accreditation is based on the evaluation of institutional self-assessments, on-site inspections, and other criteria.

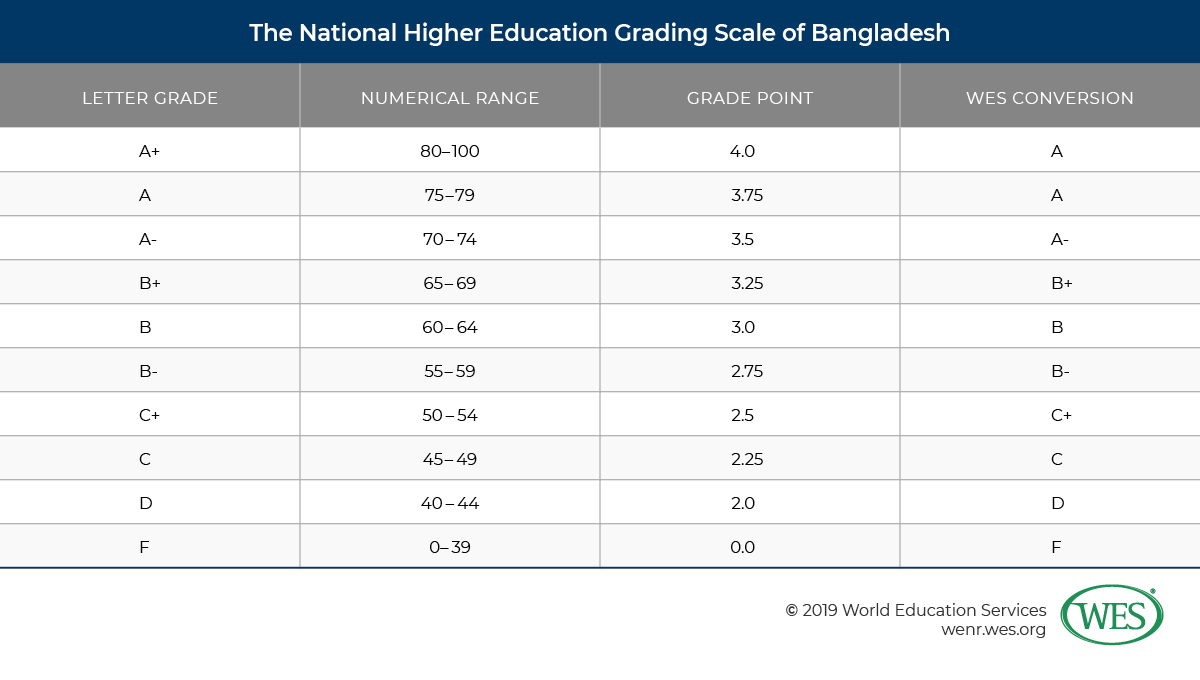

Credit System and Grading Scale

There’s no mandatory national credit system in Bangladesh—credit systems vary by institution. However, most universities use U.S. style credit systems that quantify one year of study at the undergraduate level as 30 to 36 credit units. The grading scale [120], on the other hand, is standardized nationwide. Current academic transcripts somewhat resemble U.S. transcripts. They commonly feature A to F letter grades and between two and four credit units per course.

The Higher Education Degree Structure

Bangladesh’s higher education degree structure spans bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees. At the undergraduate level, there are a number of different bachelor’s programs, which include three-year “pass” degrees, four-year “honors” degrees (spelled honours degrees), as well as longer five-year programs in professional disciplines like medicine or architecture. Older credentials like the two-year pass degree and three-year honors degree have been phased out since the early 2000s.

There are some distinctions between academic programs offered by public and private universities. While traditional, British-influenced pass and honors degrees are only awarded by public universities; private universities tend to emulate the U.S. model of education and offer four-year bachelor programs followed by two-year master’s programs. We will describe the current standard structure, but some variations do exist.

Bachelor’s (Pass) Degree

Three-year bachelor’s pass programs are mostly taught at colleges affiliated with the National University, which awards the final degree. They typically involve study in the compulsory subjects Bangla and English in addition to three elective subjects in the major. NU conducts comprehensive examinations at the end of each academic year. Common credentials awarded include the Bachelor of Arts, Bachelor of Science, and Bachelor of Commerce, but degrees like the Bachelor of Social Science, Bachelor of Business Studies, or Bachelor of Music are awarded as well. That said, pass degrees may soon be a thing of the past—the current 2010 national education policy [21] calls for the phasing out of pass degrees in favor of four-year honors degrees.

Bachelor’s (Honors) Degree

Honors bachelor’s degree programs are offered by public universities, but colleges affiliated to NU offer honors programs as well and are expected to increasingly teach honors curricula over time. Honors programs in standard academic disciplines are four years in length. They are dedicated to the in-depth study of a specialization subject and require the completion of a thesis or graduation project.

There are also four-year bachelor’s programs that are not classified as honors programs. These are usually offered by private universities. Many are U.S.-style programs that include a sizable general education component in addition to specialization studies in the major. English is a compulsory subject for all degree programs in Bangladesh.

Master’s degree

Master’s programs at public universities are usually one or one and a half years in length following a four-year honors bachelor’s degree in a related discipline with high enough grades. Holders of three-year pass degrees can also enroll in master’s programs but must complete two-year programs that require additional course work. Master’s programs at private universities are generally two years in length and typically include a thesis in addition to course work. Master’s programs at public universities may also include a thesis, but often conclude with just a final oral examination (without a thesis). Credentials awarded include the Master of Arts, Master of Science, Master of Business Administration, and Master of Commerce.

Master of Philosophy

The Master of Philosophy (MPhil) is an advanced research degree awarded only by public universities. MPhil programs last two years and require the completion of a thesis. The first year is typically devoted to course work while the thesis is written in the second year. Admission is based on a master’s degree or a four-year honors bachelor in a related discipline with high grades.

Doctor of Philosophy

The Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) is the highest academic credential in Bangladesh. It is awarded only by public universities. It takes at least two years to earn, though some programs are longer and candidates can take up to five years to complete them. Programs usually include course work in addition to a dissertation, but pure research programs also exist. Admission requires a master’s degree or the MPhil. MPhil students who completed the first year of studies with high grades but did not earn the degree may sometimes also be admitted.

Professional Education

Professional entry-to-practice degrees in medicine, dentistry, pharmacy, and other disciplines are earned after completing bachelor programs of four- or five-years’ duration. Medical and dental education take place at more than 90 medical colleges [122], most of them private. All colleges must be approved by the Bangladesh Medical and Dental Council (BMDC) and must be affiliated with a degree-granting medical university. Medical programs require five years of study followed by a mandatory one-year clinical internship. Dental programs last four years and are followed by a one-year internship. Graduates are awarded the Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery, and the Bachelor of Dental Surgery, respectively.

To practice, graduates must register with the BMDC after completing their internships, however they do not sit for qualifying licensing exams. Certification in medical and dental specialties takes another one to five years of clinical residency training, depending on the specialty.

There are also professional degree programs in alternative Asian medical systems like Ayurveda, Unani, and Homeopathy. They involve five years of study followed by a mandatory one-year internship. Taught at the Government Unani and Ayurvedic Degree College and the Homeopathic Degree College, they lead to degrees such as the Bachelor of Unani Medicine and Surgery or the Bachelor of Ayurvedic Medicine and Surgery that are awarded by the University of Dhaka. Shorter diploma programs (four years plus a six-month internship) are regulated by the Board of Unani and Ayurvedic System of Medicine and the Board of Homeopathic Medicine [123].

Professional entry-to-practice programs in law exist in two different types: Four-year undergraduate programs that lead to the Bachelor of Laws (LL.B. Honors), and two-year postgraduate LL.B. pass degree programs that are entered based on a university degree in another discipline. The latter are offered by private universities, as well as by colleges affiliated to the NU. Graduates from both programs must sit for qualifying examinations conducted by the Bangladesh Bar Council [124] to practice law. However, pass degrees awarded by NU have a poor reputation in Bangladesh and are being phased out by 2020 [125].

Teacher Education

The Bangladeshi government has in recent years taken several steps to improve the country’s teacher training system, which has been described as a “very traditional, insufficient, certificate based, loaded with theoretical knowledge, incomplete in practical learning, based on rote learning and conventional testing system [126].” These include increasing admission standards and the length of programs in elementary teacher training.

The academic requirements for teachers depend on the level of education. Elementary school teachers take a cursory two-month foundation course upon appointment and subsequently receive further training in in-service programs taught at mostly public Primary Training Institutes (PTIs) under the auspices of the National Academy for Primary Education [127]. While elementary school candidates used to be able to teach without tertiary attainment [128], teachers at public elementary schools must now hold at least a bachelor’s pass degree. Female candidates could be appointed based on the HSC until very recently, but the government in 2019 made a bachelor’s degree a mandatory requirement [129] for women as well. All teachers must start a PTI training program within three years after induction. The program used to be one year in length but was extended to one and a half years in 2010 [21]. The final credential awarded is the Certificate in Education (also known as “C-in-Ed”).

Teachers in secondary and higher secondary education, on the other hand, must undergo pre-service training and have at least a Bachelor of Education (B.Ed.). B.Ed. programs are offered by universities and teacher training colleges, which are predominantly private providers affiliated with the NU. Options include a four-year B.Ed. honors program entered after higher secondary education, as well as one-year postgraduate “top up” programs for holders of a bachelor’s degree in another discipline.

WES Documentation Requirements

Secondary Education

- Certificate (for example Higher Secondary Certificate)—photocopy submitted by the applicant

- Mark sheet/results card—sent by the Board of Intermediate and Secondary Education or Bangladesh Madrasah Education Board

Technical Education

- Mark sheet/results card—sent by the Bangladesh Technical Education Board

Higher Education

- Degree certificate (final or provisional)—photocopy submitted by the applicant

- Mark sheet/results card—sent by the institution attended

- For completed doctoral programs, a written statement confirming the conferral of the degree—sent by the institution attended

Sample Documents

Click here [130] for a PDF file of the academic documents referred to below.

- Higher Secondary Certificate

- Diploma in Engineering

- Bachelor’s Pass Degree (National University, three years)

- Bachelor’s Honors Degree (University of Dhaka, four years)

- Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery

- Master of Arts

- Master of Philosophy

- Doctor of Philosophy

1. [131] When comparing international student numbers, it is important to note that numbers provided by different agencies and governments vary because of differences in data capture methodology, definitions of “international student,” and types of mobility captured (credit, degree, etc.). The data of the UNESCO Institute Statistics provides a good point of reference for comparison since it is compiled according to one standard method. It should be pointed out, however, that it only includes students enrolled in tertiary degree programs. It does not include students on shorter study abroad exchanges, or those enrolled at the secondary level or in short-term language training programs, for instance.

2. [132] According to media reports [133], 600 out of 1,200 medical students at the University of Science and Technology that were in 2017 barred from registering with the Bangladesh Medical and Dental Council because the university violated admission quotas came from India, Sri Lanka, Bhutan, and the Maldives. Medical education in India is highly difficult to access and very expensive, so that Indians increasingly go abroad for medical education, including to Bangladesh.

3. [134] Although Bangladesh’s constitution continued to formally ensure “equal status and equal right in the practice of the Hindu, Buddhist, Christian and other religions [135].”

4. [136] Note that a handful of these institutions have been approved, but were not yet fully operational as of this writing.