Stefan Trines, Research Editor, WENR

Two years ago, we published an article [2] analyzing Germany’s efforts to integrate the estimated 1.3 million refugees that arrived in the country in 2015 and 2016, as well as the economic impact of the refugee inflow. We argued that the successful integration of the refugees, though costly in the near term, would ultimately bring substantial economic benefits to Germany’s rapidly aging society – an assumption that was based on the premise that the country would succeed in integrating the newcomers into its labor force.

The situation in 2019 remains complicated. The financial burden on the German state is high, and the presence of the refugees has triggered an intense political backlash. Chancellor Angela Merkel’s decision to open Germany’s borders in 2015 fueled the rapid rise of the right-wing party Alternative for Germany (AFD) and helped breed anti-EU populism across Europe. Merkel herself has vowed that the situation of 2015 “cannot, should not and must not be repeated [3].”

Against this backdrop it’s crucial that Germany succeed in its integration efforts and prevent the perpetuation of a social problem that fans the flames of xenophobia and nativism. The good news is that refugee integration has increased noticeably. Refugees in Germany are attending university and working in greater numbers, thereby helping to address the country’s labor shortages. Efforts to train asylum seekers have increased, and some economic benefits of the refugee influx are beginning to materialize. It’s also notable that Germany has since 2015 enjoyed substantial economic growth [4], record low unemployment rates [5], as well as record federal budget surpluses [6], notwithstanding the costs of absorbing more than a million newcomers. Despite the high number of refugees—most of whom are entitled to public welfare payments—the number of welfare recipients in Germany has actually dropped in recent years [7].

That said, the social integration of the refugees remains sluggish, and the long-term macroeconomic benefits are still difficult to gauge amid sustained high public costs and destabilizing political ramifications. A recent 2018 study [8] by French economists on the impact of asylum seekers on several Western European countries between 1985 and 2015 suggests that the economic stimuli resulting from such inflows are substantial, but they take three to seven years to materialize. It remains to be seen if Germany can effectively integrate most of the refugees in the near term and reap the potentially immense economic rewards. Integration is a long-term process and the picture is mixed thus far, but the overall trends look encouraging as of 2019.

Refugees in Germany: Some Current Facts and Figures

Since 2015, when the number of refugees coming into the country reached its peak, Germany has increasingly attempted to halt additional refugee and migrant inflows by tightening its asylum regulations. Just in June of this year, the German parliament passed legislation [9] that the advocacy group Pro Asyl has described as a “get lost law [10],” since the law facilitates and expedites the detention and deportation of denied asylum applicants.

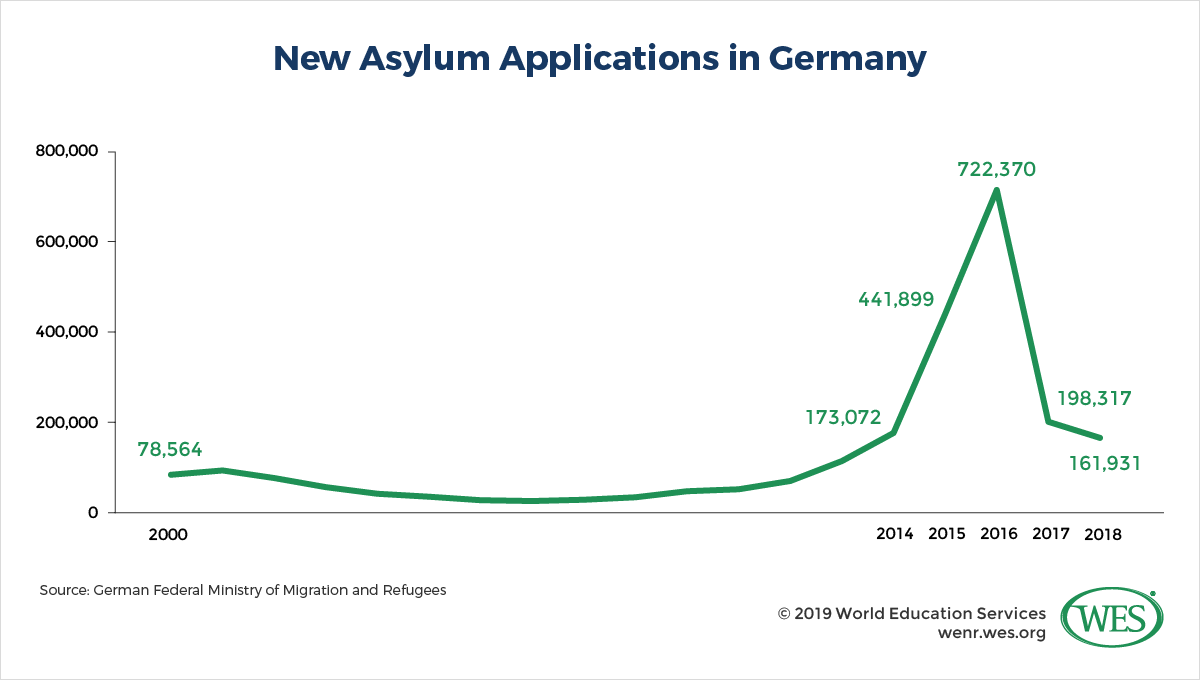

Despite such attempts, the total number of humanitarian migrants in the country keeps rising. Germany continues to receive the highest number of asylum applications in the European Union (although smaller countries like Sweden host more refugees as a percentage of the total population).

While the number of new asylum applications in Germany in 2018 has dropped nearly to levels last seen before 2015 [11], the total number of people seeking asylum or other forms of protected status increased by 5 percent [12] in 2017, reaching 1.7 million, according to the latest available official statistics.

Of these, 1.2 million [12] had been granted permission to stay in Germany as of December 2017, most of them from Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan. Most refugees coming to Germany continue to be young men—84 percent [13] of new asylum seekers in 2017 were under the age of 35, and 60 percent were male. Only a small percentage had formal occupational qualifications or academic degrees [13].

Overall, the inflow of humanitarian migrants is effecting the greatest population increase [14] in Germany in several decades. Population growth in cities like Berlin is now driven almost exclusively by citizens of other countries [15], including large numbers of Syrian newcomers [16]. Many of the new arrivals are expected to stay in Germany long term [17]. Asylees and other humanitarian migrants can apply for permanent residency permits after three to seven years in the country, depending on their legal protection status.

The public sector costs resulting from this inflow remain high. Federal expenditures allotted to asylum seekers stood at €20.8 billion [18] (USD$23.6 billion) in 2018, or a little more than 6 percent of the entire federal budget. That’s a slight decrease from €21.2 billion in 2017, but more than in 2016, when the government spent €20.5 billion. It should be noted, though, that while most of the allocations go to housing, social security benefits, and integration initiatives, about one-third is spent on preventive measures to help stem the outflow of refugees from their countries of origin.

Types of Refugee Protection in Germany

The terms used to describe humanitarian migrants in Germany can be confusing. While such migrants are usually referred to as “refugees”—a common non-legal term—the terms have specific legal meanings. Asylum [19] is granted to persons who are persecuted by state actors because of their race, religion, nationality, political beliefs, or other factors. Such persons are called asylees. Refugee status [20] is granted to persons who flee persecution by state or non-state actors as defined by the Geneva Refugee Convention—a broader definition. However, most humanitarian migrants in Germany apply for asylum, after which they are classified as asylum seekers, so the distinctions can blur. Refugees from countries like Syria often face state persecution and therefore may qualify for asylum. They’re also eligible for protection under the Geneva Convention if they’re fleeing persecution in areas under the control of the “Islamic State”.

In addition, persons who were denied asylum or refugee status may be granted temporary subsidiary protection [21] if their deportation would threaten their physical safety (by subjecting them to the death penalty, torture, or other forms of violence).

Finally, persons who do not qualify for any protection status may still be allowed to stay in Germany temporarily (prohibition of deportation [22]) if there’s the potential for their physical harm as a result of deportation, or if they cannot be deported because they lack passports or are in ill health.

[23]

[23]

Labor Market Integration

If we define integration as the chance to pursue dignified participation in the core aspects of life in a host country, the gainful employment of refugees is perhaps the most important factor for their successful integration into German society. Besides that, employing refugees not only reduces feelings of alienation among them, it also lessens public transfer payments, increases tax revenues, and helps to alleviate labor shortages.

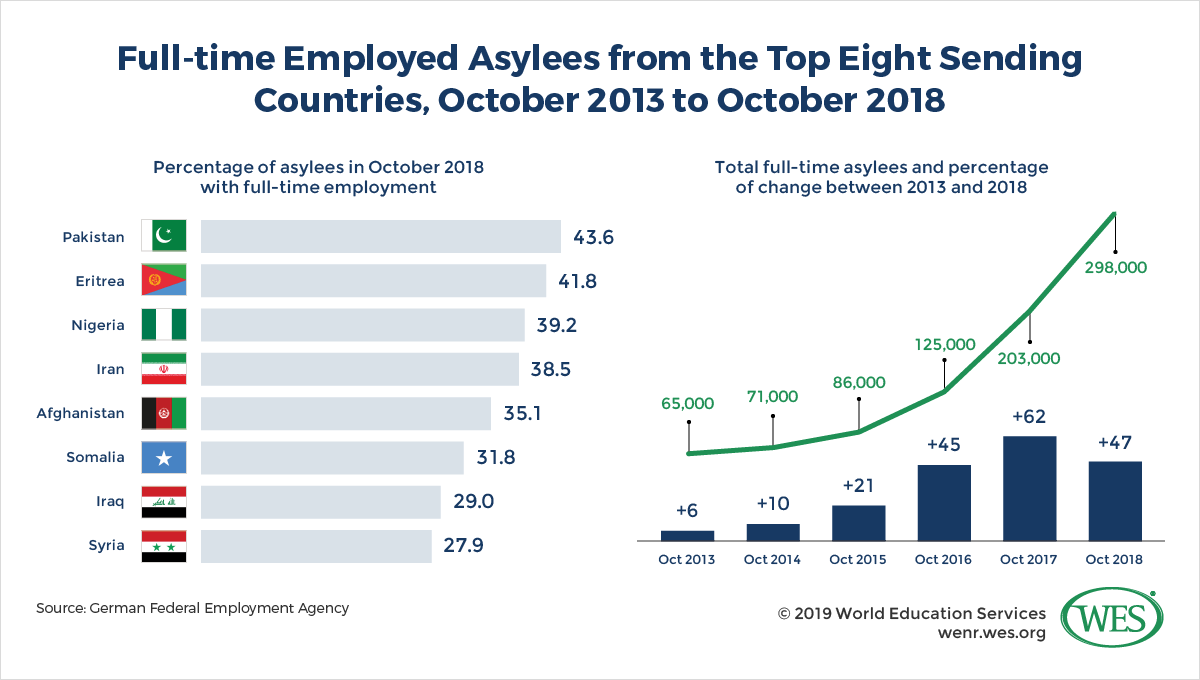

It’s therefore encouraging that refugee employment has increased significantly as of late. In fact, it has roughly tripled since early 2017. Between October 2017 and October 2018 alone, the number of employed asylees from the top eight sending countries alone grew by 47 percent, from 203,000 to 298,000 [13].1 [24] Of those from all countries, the number officially looking for work or who were underemployed decreased by 6.7 and 10.6 percent respectively, between December 2017 and December 2018 [13].

However, while these trends are positive, as many as 456,000 refugees were still looking for work and another 372,000 were still underemployed at the end of 2018. As expected, labor market integration has proven to be a slow, long-term process that takes time to gain traction. Nearly 72 percent of the recent wave of Syrian newcomers who arrived in 2015/16, for instance, were still unemployed in late 2018—the highest unemployment rate among refugees from the top eight sending countries.

Bringing most of these current asylum seekers into gainful employment is a herculean task, given the lack of German language abilities, occupational experience, and skills among many refugees. While between 8,500 and 10,000 refugees entered the German labor force each month in 2018, researchers project that some 50 percent of the recent refugees will still be unemployed five years after their arrival [26]. That percentage is estimated to drop to 25 percent only after 14 years [27]. In addition, about one-third of employed refugees are temporary workers without long-term contracts [28], and the majority of them are working in low-skilled, low-paying occupations.

On the upside, measures like the provision of cultural integration courses and other language training programs are helping to lower barriers to refugee employment. Participation in integration courses is mandatory for most refugees who lack German language competence and has undeniably boosted German language skills, which are virtually nonexistent among newly arriving refugees. According to a recently released survey of more than 7,000 asylum seekers, the share of refugees that stated that they spoke German well or very well jumped from 18 percent in 2016 to over 30 percent in 2017 [29]. Unsurprisingly, German language abilities increase over time. While only 17 percent of refugees who arrived in Germany in 2016 said they spoke German well in 2017, 48 percent among refugees who arrived in 2014 [29] said so in the same year.

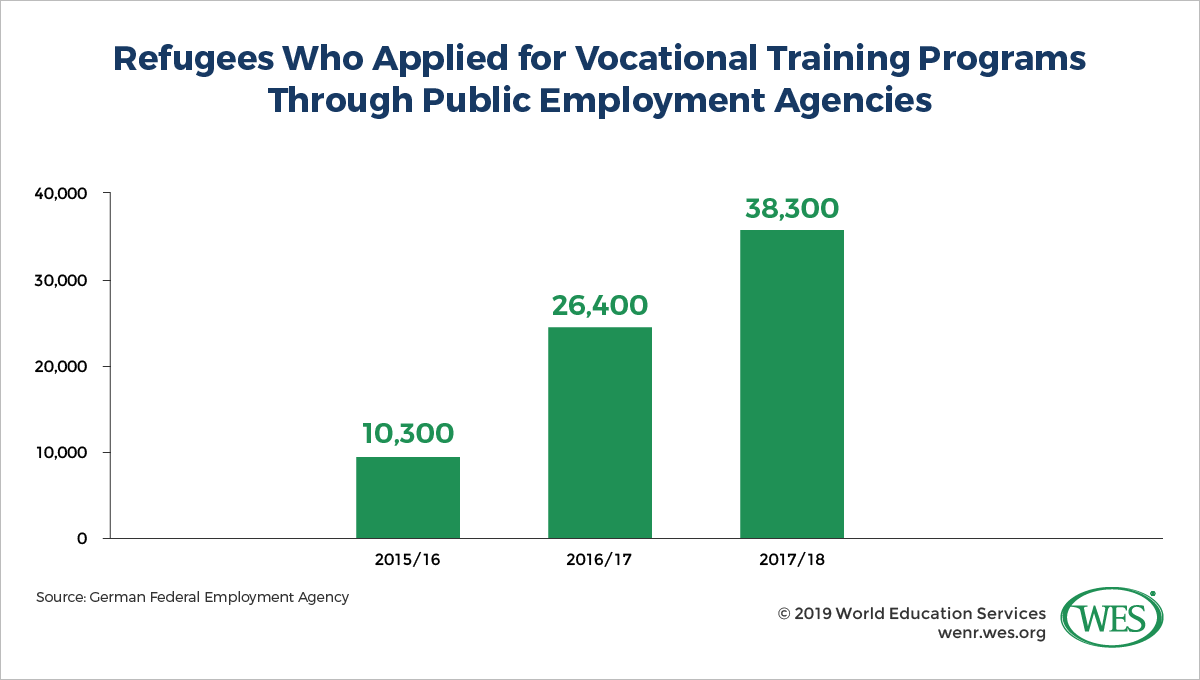

This uptick in German language ability is reflected in an increase of refugee enrollments in government-sponsored vocational training programs, for which German language skills are a mandatory prerequisite. The number of eligible refugees who applied for vocational training through public employment agencies almost quadrupled between 2015 and 2018. Of this number, 28,000 were actually enrolled in formal vocational programs (Berfufsausbildung) in 2018 [13]—an increase of 50 percent since 2017.

Employers are increasingly looking to refugees to address Germany’s growing labor shortage. Because of the aging of the population and low unemployment rates, there’s a shortage [31] not only of skilled workers but also of new entrants into vocational apprenticeship programs—a trend that is expected to significantly depress economic growth by 2035 [32].

In response, the German government seeks to recruit more workers from abroad [33] and has made it easier for asylum seekers to participate in vocational training programs. One problem was that asylum seekers who started an apprenticeship program could be deported halfway through it if their asylum claim was denied, resulting in a waste of time and resources for employers. However, the so-called 3+2 regulation [34], first enacted in 2016, now allows rejected asylum seekers to complete a three-year training program and continue working in the same company for two years—a fact that creates greater stability of expectations for employers. The rule is also highly beneficial for refugees, since they can obtain a permanent residency permit at the end of the five-year period despite being ineligible for asylum.

Labor market pressures, eased regulations, and positive experiences with employed refugees will likely entice employers to hire more of them in the years ahead. A 2017 survey of 2,000 German employers found that more than “three of four participating employers who hired refugees experienced only few or no difficulties with them in daily work, and accordingly more than 80% are broadly or fully satisfied with their work [35].”

Overall, the recent increases in labor market participation rates and growing enrollments in vocational training programs are a promising, if still inconclusive, sign that refugee integration is picking up speed to the benefit of German society. Assessing the state of refugee labor market integration in 2018, Detlef Scheele, the chairman of the German Federal Employment Agency, noted that “everything’s going quite well” and that there was “no reason for pessimism [36].”

Work Permits for Refugees

To work, all refugees need to be in Germany for at least three months and apply for an initial work authorization, which is granted on the premise that their employment doesn’t negatively affect the employment prospects of German nationals, EU citizens, or permanent residents. Once approved, asylees and accepted refugees don’t face employment restrictions for a period of three years. After three years, they can apply for permanent residency status, which includes an unrestricted work permit. Permanent residency requires proof that asylees still qualify for asylum, can financially support themselves, and have acquired adequate fluency in German [37].

On the other hand, asylum applicants and rejected asylum seekers that remain in Germany on temporary protection status, have shorter stay permits and must reapply for permits more frequently. However, they too can work and apply for permanent residency status if they are still in Germany after five years and meet certain eligibility criteria.

Participation in Education

Given that formal academic qualifications and German language abilities are a vital necessity for access to higher-skilled jobs and entry into vocational training programs, it’s crucial that refugees participate in education to the fullest extent possible.

About one-third of the asylum seekers that arrived in 2015 and 2016 were under the age of 18 [38], which means that hundreds of thousands of the new arrivals had to be integrated into the school system.

Specific regulations vary between the German states, but refugee children are generally required to have completed nine or 10 years of school until they reach the age of 18. Depending on the school they attend, most refugee children first take special integration classes that emphasize German language education before they participate in regular classes. There are also special programs that allow adults to go back to school to earn a basic German secondary school diploma (completion of Hauptschule) that qualifies them to enter vocational training programs in applied trades. In general, effective education of refugee children is complicated by teacher shortages and the fact that they are of different ages and have very different academic backgrounds. [39]

Nevertheless, only 5 percent [40] of refugee children were not attending school in 2016, according to the latest available statistics. This means that integration into the school system seems largely successful, at least in quantitative terms. It should be noted, however, that some children are too old for their respective grades, and that most are enrolled in lower level, general schools. Pupils of a migrant background are generally underrepresented [40] in university-preparatory schools and upper-secondary vocational schools. Analysts also warn of a segregated [39] and inferior school education for the refugees, because of their limited German language abilities. Despite teacher shortages, it’s crucial that German authorities find ways to speedily transfer refugee children from special needs classes to regular classes.

Refugees in Higher Education

The number of refugees enrolled in tertiary education has recently increased in earnest. It’s been estimated that 30,000 to 50,000 refugees [42] who arrived in 2015 alone were academically qualified to attend a German university. However, given their lack of German language skills, many refugees need to first enroll in preparatory or bridging courses, so that the entry of refugees into German university programs is often delayed. That also applies to large numbers of refugees who already attended higher education in their home countries—47 percent [42] of refugees enrolled in prep courses in 2017 had completed at least some university studies before arriving in Germany.

The German government supports the integration of refugees into higher education through the German Academic Exchange Service (Deutscher Akademischer Austauschsdienst – DAAD) and other institutions. Measures adopted include increased counseling and academic advising for refugees, expanded capacity for the evaluation of refugee credentials, and funding for language and academic bridging courses at universities and so-called Studienkollegs [43], which are generally one-year courses that combine language training with education in basic knowledge and terminology of the intended major.

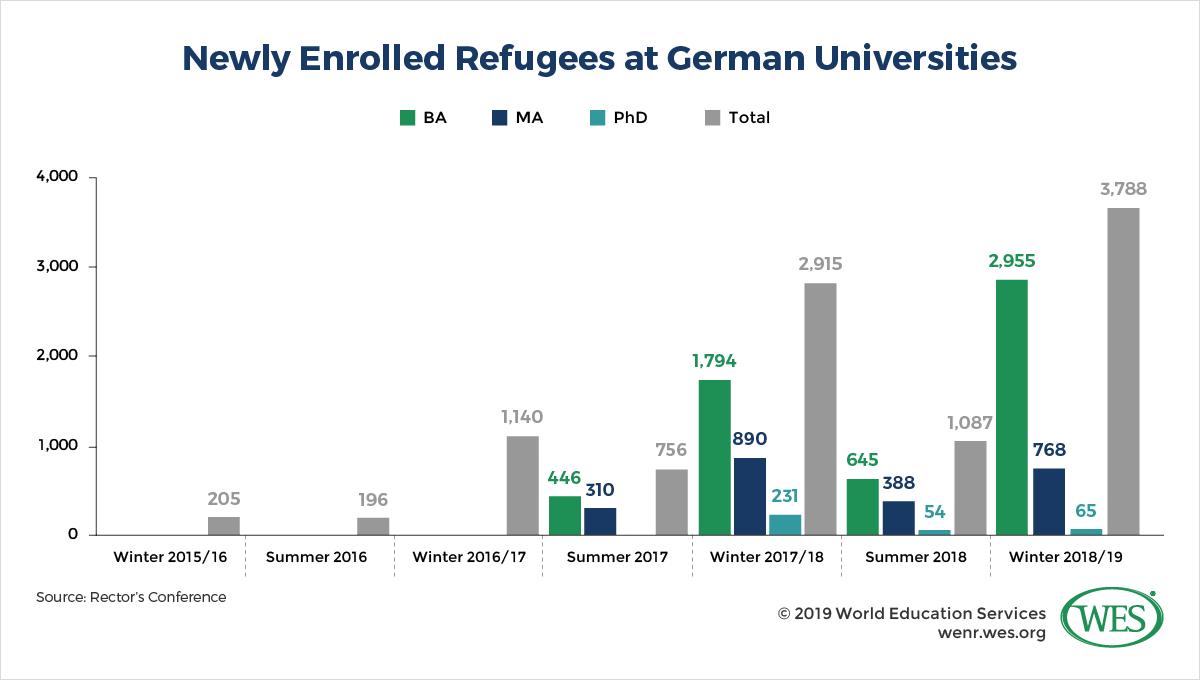

These measures have begun to bear fruit. While it is difficult to quantify the number of refugees enrolled at German universities because higher education institutions don’t collect data on refugee status, surveys by the Rector’s Conference, Germany’s university association, show that the number of newly enrolled refugees jumped from merely 205 in 2015/16 to 3,788 in the 2018/19 winter semester [44]. In total, the number of refugees who enrolled at German universities is said to have increased almost 10-fold [45] over the past three years, from 1,100 in 2016 to around 10,000 in 2019.

Syrians are by far the largest group among these students—they are now the sixth-largest group [42] of foreign-educated students in Germany (up from being the 16th largest [46] in 2017). According to the latest available statistics, the number of Syrian nationals enrolled in German universities increased by 69 percent between 2017 and 2018, from 5,090 to 8,618 [47].

Most refugees are enrolled at the undergraduate level—only 22 percent of newly matriculated refugee students in the 2018/19 winter semester were enrolled in master or PhD programs. However, the number of refugees in German higher education can be expected to increase significantly at all levels in the years ahead as more refugees qualify for entry into higher education programs, and for progression into graduate programs. The think tank and advocacy group Stifterverband [49] estimates that the number of refugees at German universities will quadruple to 40,000 by 2020 [50].

University Admission of Refugees

For admission into university, individuals who were educated abroad, including refugees, require an upper-secondary school leaving qualification that is recognized as equivalent to a German university-preparatory school diploma. These individuals usually need to submit their credentials for equivalency assessment by the non-profit organization uni-assist [51]. Refugees can apply to three universities per semester free of charge through uni assist. They may also need to sit for the Test for Foreign Students (TestAS [52]), and they generally need to demonstrate German language skills corresponding to levels B2 or C1 of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages.

Refugees who lack academic documents may still be admitted based on interviews or aptitude tests, but most universities require students who lack adequate credentials to enroll in preparatory courses that conclude with a formal equivalency examination (Feststellungsprüfung).

Integrating the Refugees Is a Marathon, Not a Sprint

The fact that about two-thirds of the refugees who arrived in Germany in recent years are still un- or underemployed is causing many observers to paint a grim picture of failed integration and to raise the specter of detached “parallel societies” dwelling in social problem zones at the margins of German society. There are certainly major problems with many of the current integration efforts. Too many refugees, for instance, live for too long in isolation from German society in asylum shelters, waiting for open spots in integration courses or unable to work because of lengthy bureaucratic approval procedures [53]. The overcrowded integration courses are often ineffective: Less than half of all refugees that completed one of the courses were able to pass even a basic language test [54] in 2018.

However, focusing primarily on such problems ignores the fact that the integration of so many refugees from different cultural and religious backgrounds without German language abilities or transferable skills simply does not happen overnight, especially in a society like Germany’s, which lacks a long tradition as an immigration country. Given these prohibitive structural conditions, integration is, in fact, proceeding remarkably well.

Educating and upskilling most of the refugees will take time, but refugees are currently gaining access to both the labor market and higher education at accelerating speed. We are therefore cautiously optimistic that the overall situation may improve substantially in the years ahead—especially since the country is in such need of laborers.

The shortage of skilled labor in Germany has already become so acute that its economy could not have performed so strongly in recent years without the inflow of large numbers of labor migrants, mainly from other EU countries.

Given the rapid aging of German society, labor needs will only continue to grow: Germany’s working-age population is projected to further shrink by four to six million people until 2035 [55], increased immigration notwithstanding. As German migration researcher Wolfgang Kaschuba recently warned, if “Germans want to maintain their economic well-being, we need about half a million immigrants every year. We need to guarantee that our society stays young, because it’s aging dramatically [56].”

Countries like Canada seek to address their labor shortages by importing highly skilled immigrants from around the world. The comparatively low-skilled refugee population in Germany hardly fits the profile of skilled immigrants recruited through such immigration programs. Yet, if Germany succeeds in effectively educating, training, and upskilling the mostly young refugees, it will greatly enhance the composition and age structure of its labor force and inject productive potential into its economy. Educating and skilling the newcomers is a win-win situation for both the refugees and German society at large.

In the meantime, the continued presence of the refugees remains a polarizing topic in Germany. The country’s political system is under growing pressure from ethnonationalist movements that exploit the refugee inflow for political mobilization. It’s critical that government authorities, companies, and universities all expedite their integration efforts and remove any remaining barriers to integrate the refugees as full-fledged participants in the German economy and society as soon as possible.

1. [57] This number includes only employees that are required to pay social security taxes in Germany. It does not include independent contractors and businesspeople, nor persons who work but do not earn enough income to pay taxes (part-time employees or others).

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of World Education Services (WES).