Stefan Trines, Research Editor, WENR

A Look at the Country’s Marketing and Recruitment Strategies

Germany has become an increasingly important player in international education in recent years. According to UNESCO data [2], in 2016 the country overtook France in international student enrollments to become the fourth-largest host country of international students worldwide after the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia. Germany has become an attractive study destination far beyond Europe—India recently emerged as a top sending country of students to Germany, and there’s a growing inflow of students not only from China but also from places like Iran, Cameroon, Tunisia, Indonesia, and Pakistan. Germany is simultaneously the world’s third-largest sending country of international students, after China and India.

Given that Germany is not an English-speaking nation, its growing attractiveness as an international study destination is remarkable. Its appeal would not be possible without the well-organized, well-funded internationalization and marketing strategies pursued by the country’s government and higher education institutions (HEIs). This article describes Germany’s current trends in inbound student mobility and profiles the steps the country has taken to facilitate student inflows. It then concludes with an analysis of where international students in Germany are coming from.

Current Trends in International Student Inflows to Germany

Growing international student mobility is a global trend. In the two decades between 1998 and 2017, the number of international students enrolled in degree programs outside their home countries spiked from 1.95 million to 5.3 million [2] worldwide. Within that context, Germany is part of a group of countries that include Australia, Canada, and China, all of which have absorbed ever-larger numbers of these mobile students—increasingly at the expense of the declining top destination country, the United States.

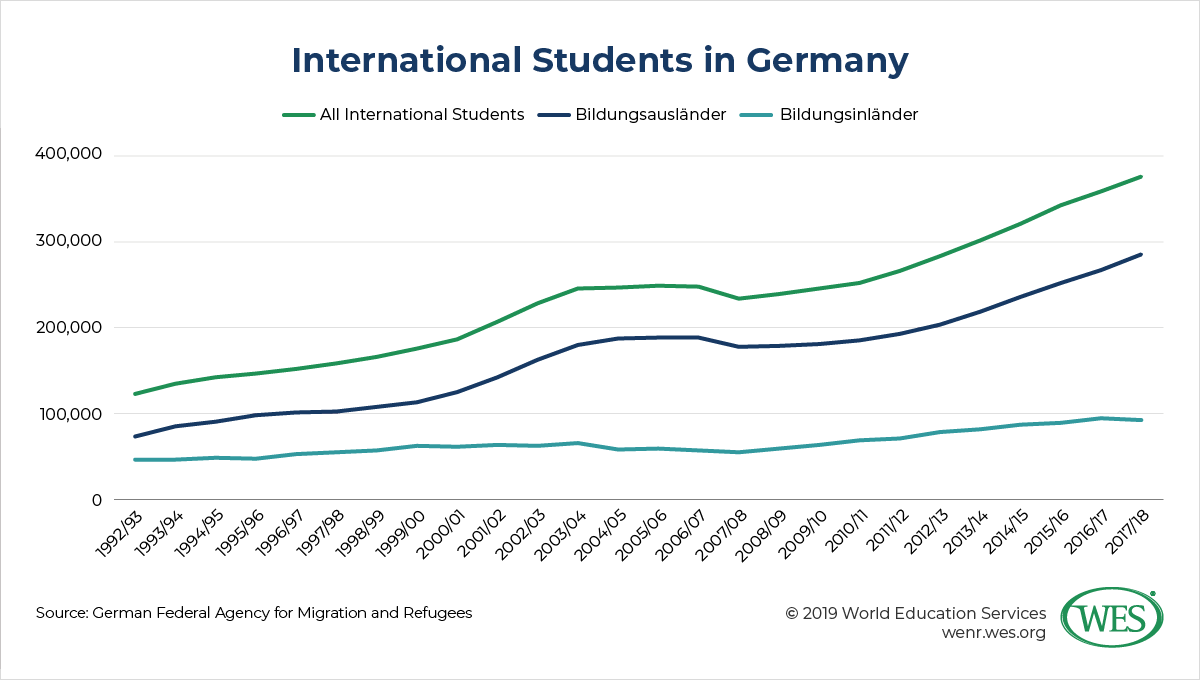

Student data [3] published by the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD—Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst) and the German Center for Higher Education Research and Science Studies show that the number of international students in Germany recently surged from 282,201 in 2013 to 374,583 in 2018 (an increase of 33 percent). This rapid uptick followed a continual rise in international student enrollments since the early 1990s that was only briefly interrupted during the Great Recession of 2008/09. Fully 13 percent of all students in Germany are now international students (up from 11 percent in 2013). For comparison, international students made up only 5.5 percent of all U.S. students in 2018 [4].

How Germany Counts International Students

UNESCO, government agencies, and organizations like the Institute of International Education use different methods to count international students. The numbers these entities report vary because of differences in data capture methodology, definitions of “international student,” and types of mobility captured (credit, degree, and so on). One particularity of the way Germany defines international students is that it considers as “foreign students” both so-called “Bildungsinländer” and “Bildungsausländer.” Bildungsinländer are non-German nationals “who have obtained their higher education entrance qualification in Germany, while Bildungsausländer are students of other nationalities who have obtained their higher education entrance qualification outside Germany. Bildungsinländer have usually lived in Germany for a long period and attended a German school before going to university … whereas Bildungsausländer usually come to Germany primarily in order to study [5].” This WENR article focuses on Bildungsausländer.

The Economic Importance of International Students

The fact that Germany in 2017 hosted 358,895 international students means that the country effortlessly exceeded its official recruitment target of 350,000 international students by 2020 three years ahead of schedule. Setting such official recruitment quotas is relatively new for Germany, but this increasingly common practice has been adopted by various countries worldwide—from China [7] to India [8], Japan [9], Korea [10], Malaysia [11], Russia [12], Poland [13] and Sri Lanka [14]—and is an indication of the intensifying global competition over international students and skilled workers.

Germany is one of the world’s fastest aging societies, and its need for imported skilled talent is acute. The country already lacks more than 300,000 tech workers [15] and is experiencing a skilled labor shortage that is expected to depress economic growth [16] by 2035. In response to these challenges, Germany in 2013 adopted an internationalization strategy [17] that sought to attract the world’s “smartest minds” and boost international student enrollment by more than 30 percent within seven years. International graduates are excellent candidates for skilled labor immigration. They are relatively young and already familiar with the country; they have German academic qualifications and often speak at least some German.

The academic benefits of international students are obviously huge as well. International students bring with them different perspectives and academic approaches, and thereby often enrich and diversify the academic discourse and raise the quality of education. Their presence in German classrooms also increases the intercultural awareness of German students.

Finally, international students directly stimulate the German economy. As Germany’s Federal Minister of Education observed in 2014, international students “invest, consume, pay taxes and save jobs [18].” One 2013 study [19] by the economic research institute Prognos found that consumption by international students generated 400 million euros (USD$437 million) in tax revenues and created 22,000 jobs in 2011 alone. Since education in Germany is predominantly public and tuition-free, the state shoulders considerable costs, but these expenditures are estimated to amortize once 30 percent of international graduates stay and work in Germany for five years.

Finally, international students directly stimulate the German economy. As Germany’s Federal Minister of Education observed in 2014, international students “invest, consume, pay taxes and save jobs [18].” One 2013 study [19] by the economic research institute Prognos found that consumption by international students generated 400 million euros (USD$437 million) in tax revenues and created 22,000 jobs in 2011 alone. Since education in Germany is predominantly public and tuition-free, the state shoulders considerable costs, but these expenditures are estimated to amortize once 30 percent of international graduates stay and work in Germany for five years.

The stay rate of international students in Germany is generally on an upward trajectory. It stood anywhere between 35 percent [20] and 50 percent in 2012, depending on the source of the estimate, although the duration of stay varied. It should be noted, however, that dropout rates are high: 41 percent [21] of international bachelor’s students did not complete their program in 2014 (compared with 28 percent of those enrolled in master’s programs). For comparison, 28 percent [22] of all German bachelor’s students and 19 percent of master’s students do not complete their studies, according to the latest available statistics.

Germany’s Marketing and Recruitment Strategies

The decentralized structure of the German education system means that the country’s internationalization and marketing strategies are shaped by various stakeholders, including universities, research institutes, the federal government, and the governments of the 16 German states, which set education policies within their respective jurisdictions.

Academic institutions and government actors have somewhat divergent interests. While the federal government naturally pursues a macro-economic approach, HEIs and states are more concerned about their institutions and regions. That said, while individual HEIs have varying internationalization strategies, fostering student mobility is a shared goal. Large-scale marketing programs are coordinated and steered by national bodies like the DAAD, the German Council of Science and Humanities, and the German Rectors’ Conference, the country’s university association.

Concerted efforts to boost international student mobility to and from Germany are closely intertwined with the Bologna Process, which seeks to increase academic mobility to elevate the global standing of the European Higher Education Area and fosters European integration. However, that is not to say that there aren’t national strategies in place. The strategic marketing of the German higher education system first gained traction in the 1990s when the focus of internationalization efforts shifted from academic and cultural benefits to a more utilitarian approach. Concerns that Germany would miss out on “brain gain” and lose talented domestic students and scientists to Anglo-Saxon countries (brain drain) resulted in proactive programs to strengthen the global competitiveness of German higher education [23] and promote a welcoming culture to attract more international talent.

Many of the initiatives adopted during these early phases are still in place today. They include GATE-Germany [24], a collective marketing consortium of Germany’s universities that promotes German higher education at conferences and trade fairs, or through webinars, ad campaigns, official delegation visits to other countries, and through an online database of international study programs in Germany. As the DAAD described it, the use of “targeted marketing measures, such as fairs or information events” is “to paint an accurate picture of life in Germany and help to make young talents perceive Germany as an attractive place for studying and research [25].”

Other marketing campaigns include “Research in Germany – Land of Ideas [26]” and “Study in Germany – Land of Ideas [27],” funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research. The communications strategy of the latter is “to have students, graduates and researchers currently in Germany” as well as alumni from German institutions “describe their positive experiences in Germany.” These student testimonials are marketed in advertisements and brochures and on websites based on the premise that alumni are good brand ambassadors. The general approach is to brand Germany as one of the world’s top destinations for research and innovation [28]. Other strengths like the global reputation of German universities, the availability of scholarship funding, and the fact that education in Germany is tuition-free in almost all German states are highlighted as well.

The German Academic Exchange Service (Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst – DAAD)

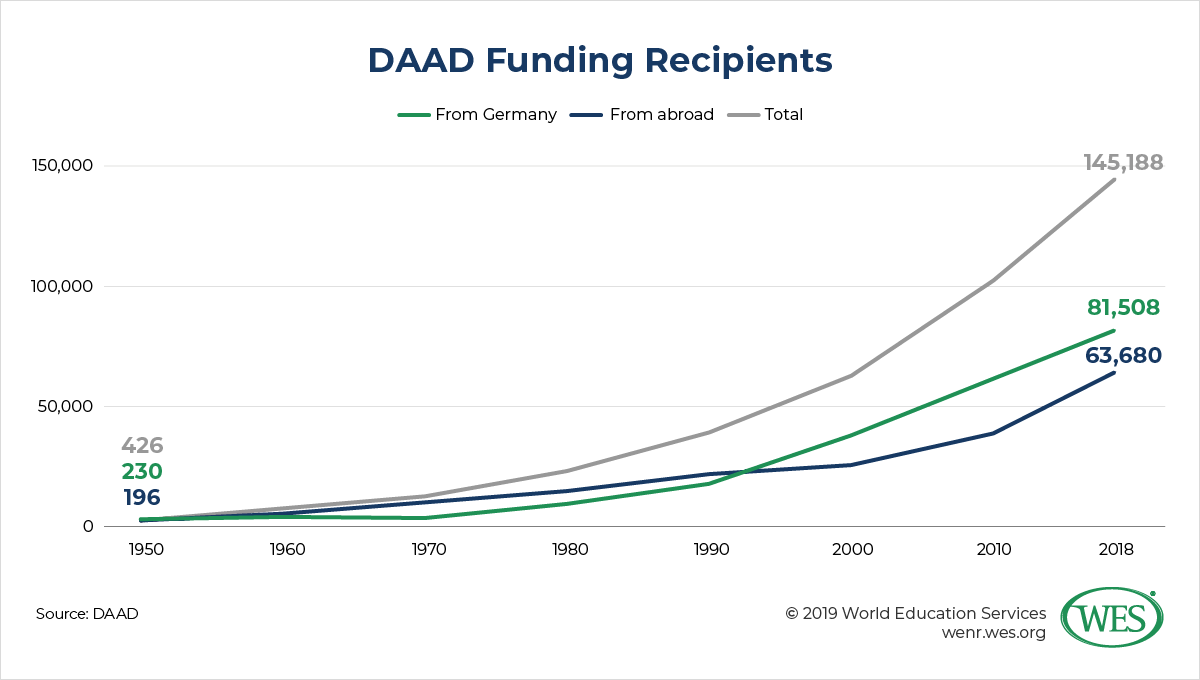

With the DAAD, Germany has established a formidable agency to represent and promote German higher education on the world stage. Founded in 1925, the DAAD is now the world’s largest funding organization for academic exchange supporting some 145,000 German and international students and researchers in 2018 [29] alone. In addition, it promotes the internationalization of German universities and Germany as a study destination. The DAAD engages in research, provides information on the education systems of other countries, and supports transnational partnerships and German language programs abroad, among other activities. It also provides development aid by supporting knowledge transfer and helping other countries to strengthen their education sectors, notably in sub-Saharan Africa, Central Asia, China, and Eastern Europe.

The DAAD is a self-governing association of more than 350 German HEIs and their student bodies. It has more than 900 employees [30] and an annual budget of 558 million euros [29] (USD$611 million) in 2018, most of it coming from the foreign ministry and other federal ministries, as well as the European Union. The organization has 15 regional offices and 57 information centers all over the world.

Lowering the Language Barrier

While Germany is generally well-suited to be an international education hub, the fact that German is not a language widely spoken throughout the world is a significant handicap. Even though many international students from Eastern Europe and elsewhere have good German language skills, the language barrier makes it difficult to pass the language tests required for admission to German HEIs and contributes to the high dropout rates among international students in Germany. It also limits the pool of potential international students in Germany.

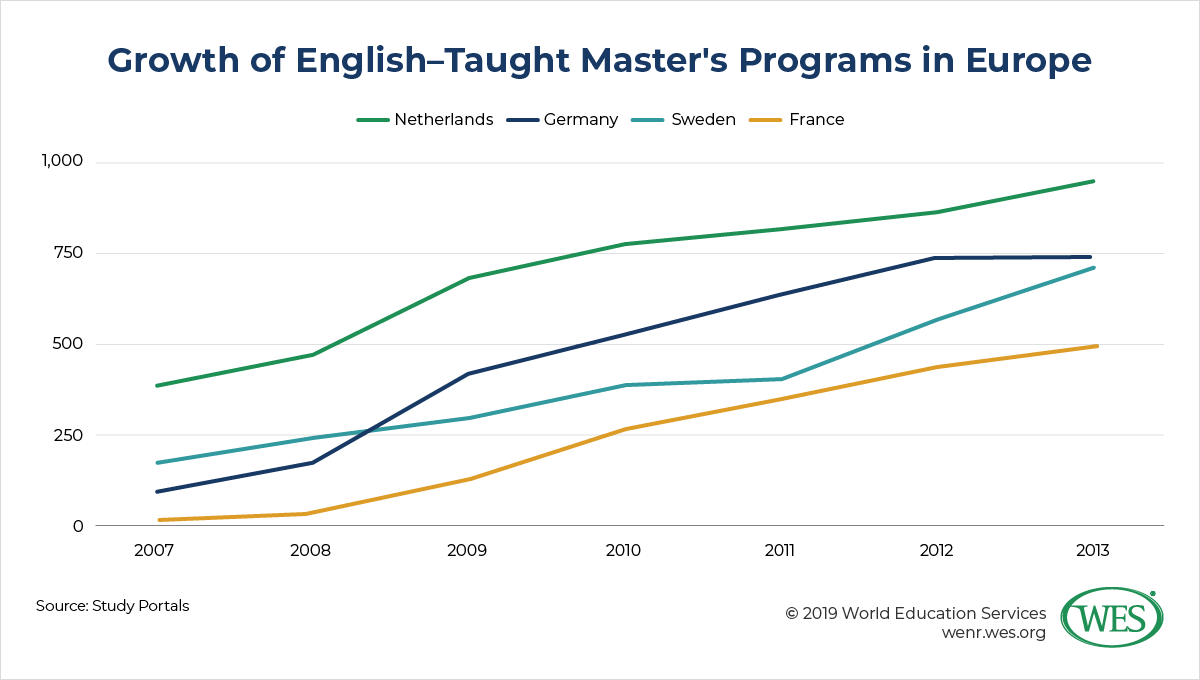

Great emphasis has therefore been placed on the development of English-taught international study programs. The number of these programs has grown exponentially since the mid-2000s, if mostly at the graduate level in the form of new Bologna master’s degree programs. Between 2007 and 2013, the number of English-taught master’s programs jumped from less than 100 to more than 700 in 2013, before reaching 1,268 in 2019 (according to an official database [31] of academic programs provided by the German Rectors’ Conference). This increase has greatly expanded the study options for international students, and further growth of English-language offerings is expected.

However, bachelor’s programs taught in English are still uncommon. Merely 233 were offered in Germany in 2019–a share of less than 3 percent [33] and far below comparable percentages in countries like the Netherlands or Sweden (23 percent of all Dutch bachelor’s programs were taught in English in 2018 [34]).

Fully 167 out of 398 German universities did not offer any English-taught programs at all in 2017. The German Council of Science and Humanities therefore recently urged [33] universities to offer more programs in other languages (as long as doing so does not affect academic quality, and German is preserved as the main academic language). While the council noted that languages like Chinese or Arabic might make sense in some circumstances, it’s all but certain that almost all of these programs will be offered in English. It’s also important that auxiliary support services be provided in English.

I used to study in the … United States and what changed my mind was I read an article about how affordable the education here is and that made me think about looking for a programme here, because I’ve never thought about coming to Germany before. I think what sealed the deal for me was, I found two schools in Germany for astrophysics and when I found out that they’re in English, that sealed the deal [35].” (International student at the University of Bonn, 2017)

Money Matters: Scholarship Funding

Tuition-free education in Germany is a major draw for international students. This was underscored by an immediate 19 percent [36] decrease in international enrollments when the state of Baden-Württemberg introduced modest tuition fees of 1,500 euros per semester for students from non-EU countries in 2017—the only German state to do so thus far.

Needless to say, scholarships are another big motivator for international students, particularly for those from low-income countries. Thus, they are an important element of the internationalization strategies of various countries [37]. In Germany, measures like scholarship funding are critical to inbound mobility, because most universities aren’t dependent on tuition fees and have little incentive to bring in international students for purely economic reasons—unlike HEIs in countries like the U.S. [38], Australia [39], or Canada [40], where a fair amount of universities milk international students as cash cows.

The DAAD is by far the largest provider of scholarships, most of which are funded by the federal government. Spending on these scholarships, which are mostly provided for graduate studies, has ramped up in recent years. The number of international students receiving DAAD funding more than doubled from 37,451 in 2000 to 81,508 in 2018 [29]. In addition, scholarships are provided by state governments, universities, philanthropic foundations, and research organizations. The DAAD also administers scholarship programs funded by governments of other countries.

Available scholarships include funding for full-fledged degree programs, as well as for short-term study or research visits of a few weeks or months. Overall, there’s a great emphasis on promoting advanced research—49 percent [41] of all international PhD students in Germany received funding in 2018. While some scholarship programs are open to all students, some are limited to those from specific world regions. The largest number of scholarship recipients in 2018 came from the Middle East and North Africa [29] (MENA). Average scholarship amounts in 2016 ranged from 408 euros a month for undergraduate students, to 642 euros for master’s students, to 1,139 euros [42] for PhD students. The DAAD provides a database [43] of available scholarship programs on its website.

Work and Residency Requirements

Inbound student mobility to Germany is driven by a variety of factors, including increased transnational academic cooperation and the development of growing numbers of dual degree and double degree programs with partner institutions in other countries. Another crucial element is the availability of work opportunities for students. Current trends in international student mobility show a strong correlation between the attractiveness of countries as study destinations and their willingness to give international students viable immigration pathways and allow them to stay and work after graduation. Whereas Canada’s increased openness to immigration has resulted in surging student inflows from all over the world, increased restrictions on post-study work opportunities in destinations like the U.S. and the U.K. [45] have resulted in declines.

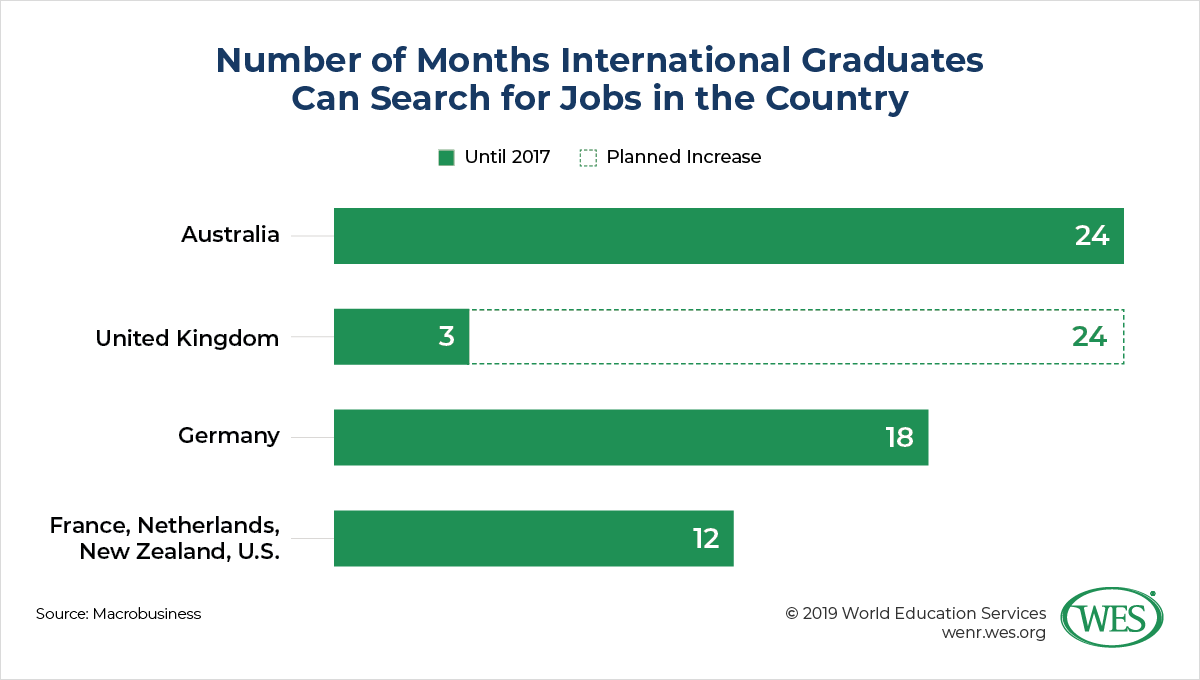

Germany has in recent years streamlined its residency requirements for international students from non-EU countries. In 2012, it extended the time international students can stay in the country to look for work after graduation from 12 to 18 months. During that period, students can work without restrictions. Those that find a job in a field related to their degree—and that pays a minimum threshold salary1 [46]—are then entitled to the EU Blue Card [47], a residency permit that since 2012 has been available to international graduates and highly skilled workers in Germany. The card is valid for four years and allows holders to bring their spouses and children into Germany and to apply for permanent residency after 33 months. The card also opens pathways for eventual citizenship and migration to other EU countries. The current regulations therefore open long-term migration possibilities for international students, if they have adequate German language abilities and can find well-paid skilled employment.

Countries of Origin

Compared with expatriate students in other international study destinations like the U.S. and Australia, where students from China and India make up more than half of all international students, the international student body in Germany is more diverse. Given the internationalization and standardization of European education systems in the Bologna Process, there is a great deal of intra-European student mobility to and from Germany. It has become increasingly common for European students to spend a semester abroad, and there is ample funding available for such short-term study visits, notably through the EU’s Erasmus+ [49] program, which provided funding for 22,300 international students in Germany in 2017 [5]. It should be noted, however, that 90 percent [41] of international students in Germany are degree-seeking students.

Unsurprisingly, European countries like neighboring Austria, France, Italy, Poland, and Spain are major sending countries of international students to Germany. So are Ukraine and Russia, with the latter having long been the second-largest country of origin of international students in Germany, most of them women. In fact, Germany is by far the most popular destination country among mobile Russian students, as well as one of Russia’s most important trading partners. According to GATE-Germany [50], Russians are drawn to Germany because of its geographic proximity, a long tradition of academic exchange between the two countries, relatively widespread German language abilities in Russia, and the good reputation yet low cost of German education. Better employment opportunities [51] in Germany, demand for skilled labor by German companies in Russia, and a growing number of dual and joint degree programs offered by universities in both countries also play a role.

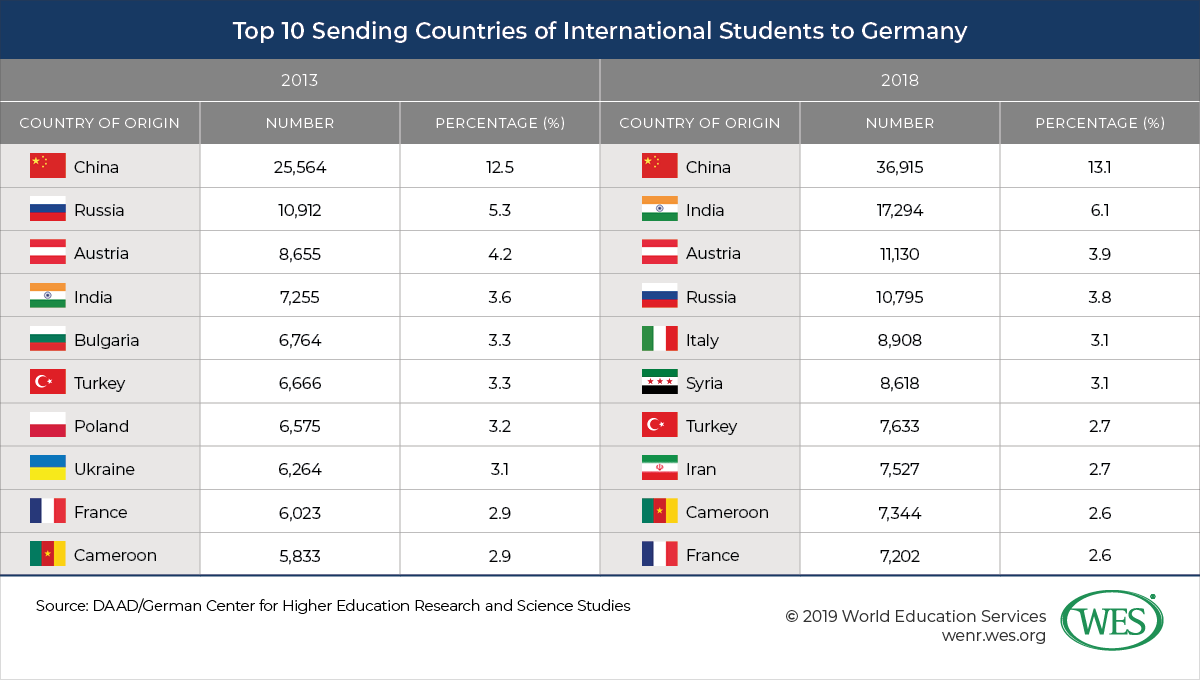

However, the success of Germany’s recruitment strategies is perhaps best reflected by the rapid growth of student enrollments from Asian and MENA countries. While enrollments of Russian students stagnated and slightly declined over the past five years, the number of Chinese students spiked by 44 percent while India swiftly became the second-largest sending country after Indian enrollments surged by 183 percent between 2013 and 2018 [5]. These developments reflect Germany’s evolution from a somewhat “exotic” international study destination to those outside of Europe to one that’s more globally relevant.

China

China has been the top sending country of international students in Germany by a large margin for the past decade. In 2018, Chinese students made up 13 percent (36,915 [53]) of all international students in Germany. Most of them are graduate students enrolled in engineering, computer science, and natural science programs [41]. According to surveys [54], many Chinese students and their parents are attracted to Germany by the prospect of tuition-free, English language education at reputable institutions, most typically at technical universities. Interest in German culture, a positive image of the country in China, and students’ desire to enhance their employment prospects are also important factors.

Germany has in recent years emerged as a top destination country [55] among mobile Chinese PhD students worldwide. However, while Chinese enrollments in graduate programs are surging, relatively few Chinese stay in Germany after graduation, and dropout rates are high. Language barriers [56] and social isolation are often cited as the biggest problems [57] for Chinese students abroad.

Evaluating Credentials from Other Countries

The rising inflow of international students to Germany has caused an increasing need for the evaluation and vetting of foreign academic credentials. In Germany, the main actor in this field is uni-assist [58], a non-profit organization that is funded by application fees. Originally founded in 2003 by 41 German universities, the DAAD, and the German Rectors’ Conference, uni-assist has grown at a robust pace in recent years. It now serves more than 180 German universities [59] and processes about 300,000 applications [58] annually from some 180 countries.

India

Students from India, the world’s second-largest sending country of international students after China, are increasingly diversifying their study destinations in a shifting global environment. The Trump effect is turning students away from the U.S., and growing numbers of countries are competing over Indian students. In Europe, countries like France and the U.K. are all eager to recruit more Indian students [60], but Germany is increasingly edging out this competition.

Within just four years, Indian student enrollments in Germany doubled, resulting in India overtaking Russia as the second-largest sending country of international students, as previously noted. In 2018, there were 17,294 Indian students [53] in Germany, accounting for 6 percent of all international students. The number of Indian degree students in the U.K., by contrast, dropped from 22,155 in 2013 to 16,241 in 2017, according to UNESCO.

Given Germany’s excellent engineering study programs and its low tuition fees, the country is in many ways an ideal study destination for Indians. The most typical Indian mobile student worldwide is a graduate student of engineering or another STEM discipline—a profile that closely matches the Indian students in Germany. Almost all study at the graduate level. Some 80 percent are enrolled in master’s programs, more than 70 percent study engineering, and 14 percent prsue studies in another STEM discipline [53]. The vast majority are degree-seeking students; it’s uncommon for Indians to come to Germany on short-term study visits.

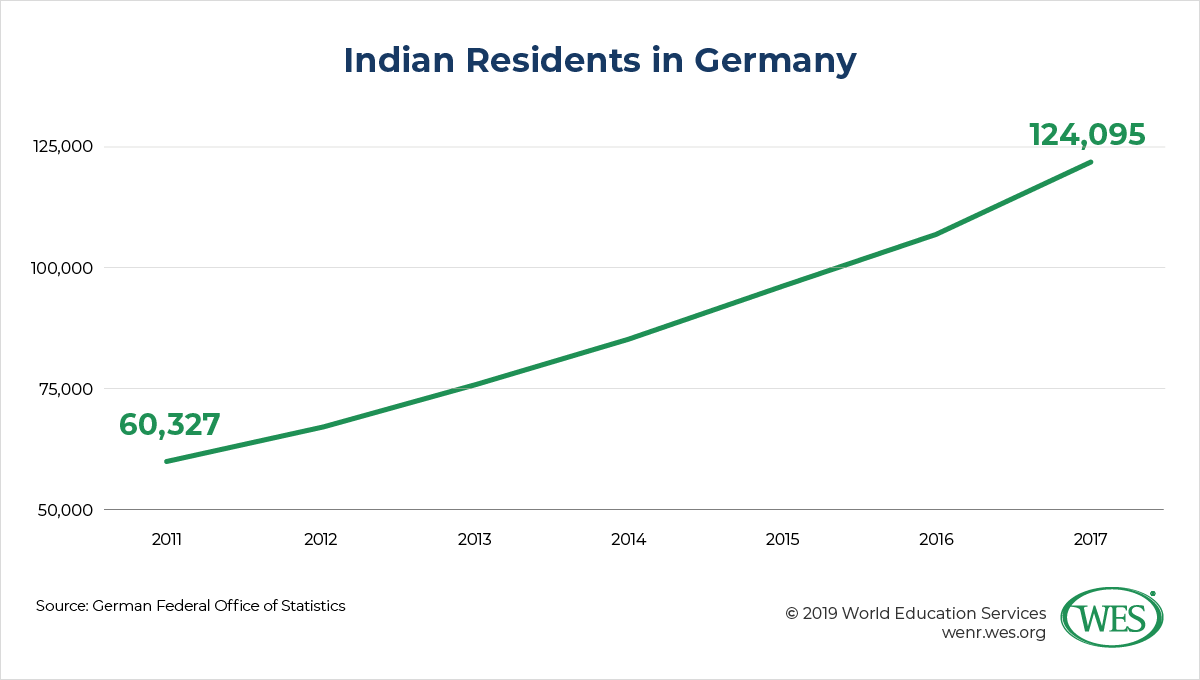

However, despite Germany’s favorable attributes, the country stayed largely off the radar screen of Indian students until recently. One factor that changed Indian perceptions was the growing availability of English-taught master’s programs in STEM fields. Virtually all Indian students in Germany are enrolled in English-taught programs [61]. Equally important to Indian students are post-study work opportunities and immigration pathways, so the introduction of the EU Blue Card in Germany was a pivotal catalyst. A disproportionately high share of Indians—23 percent [62]—held Blue Cards in Germany in 2018. To put this in perspective, Indians make up only 1.2 percent of all foreigners living in the country. Their number is rising rapidly, however, and has recently more than doubled—from 53,386 people in 2011 to 124,095 in 2018 [63].

It’s highly likely that the inflow of Indian graduate students to Germany will continue to rise. On the supply side, rising incomes coupled with a scarcity of high-quality study options in India will continue to push Indian students overseas for years to come. Germany, meanwhile, is India’s second most important research partner [61] after the U.S., as reflected in various collaborations on large-scale research projects, such as the Indo-German Science & Technology Center [65] near New Delhi. The project is funded jointly by both governments with four million euros [66] annually. There’s also a growing number of joint research publications and transnational university partnerships. The two countries in 2015 inked a formal strategic partnership [67] in higher education cooperation.

It’s also notable that a survey of international students [68] conducted by GATE-Germany in 2016 revealed that 93 percent of Indian students were satisfied with their study experience in Germany—the highest percentage among all countries polled. Satisfaction was highest with engineering programs. There’s even surging demand [69] in India for German international high schools and German language training in general.

MENA Countries

In addition to China and India, MENA countries like Syria, Iran, Tunisia, and Morocco recently accounted for rapid increases in international student enrollments, if for varying reasons. For example, since 2015 the number of Syrian students in Germany has tripled, mostly because of the more than 700,000 Syrian refugees in Germany, most of whom arrived after the summer of 2015. Although the integration of these refugees into the German higher education system continues to be a challenge [70], the number of enrollments of Syrian students has spiked in recent years. While Syria did not register among the top 20 sending countries in 2013, Syrians are now the sixth-largest group of internationally educated students in Germany, after enrollments increased by 69 percent between 2017 and 2018, from 5,090 to 8,618 [71].

The number of Iranian students also surged—there were 7,527 Iranian students in Germany in 2018 compared with 4,928 in 2013 (an increase of 53 percent). Following the suspension of the UN nuclear sanctions on Iran in 2016, Germany became a natural partner in Iran’s attempts to modernize and internationalize its education system—a development rooted in a long tradition of commercial ties and academic exchange that continued despite the international isolation of Iran under the UN sanctions. Even before the sanctions were suspended, the DAAD in 2014 re-opened an information center in Tehran [72]. The organization has since ramped up scholarship funding and support for German language training in Iran [18]. Like Indian students, mobile Iranian students are predominantly graduate students enrolled in STEM programs. It’s also likely that Germany, which tends to be viewed as the most popular Western country [73] in Iran, is benefiting from deteriorating U.S.-Iranian relations and the greater number of hurdles students from Muslim countries encounter in the U.S. now under the Trump administration.

Tunisia and Morocco are other MENA nations that are increasingly important sending countries of students to Germany. Amid quality problems in domestic higher education and high youth unemployment [74], students from these countries increasingly head to Germany, attracted by the reputation of the country’s universities, the low cost and applied nature of many of its study programs, and the favorable prospects for employment [75] there. Germany is the second most popular destination country among Tunisian students after France—Tunisia’s former colonial power—and the third most popular destination among Moroccan students, according to UNESCO. The number of Tunisian and Moroccan students in Germany has increased by 87 percent [53] and 12 percent, respectively, since 2015.

Conclusion: The Challenge of Increasing Student Retention

Trends in inbound student mobility in Germany in recent years show that Germany has become an international study destination for an increasingly diverse international student body beyond traditional European sending countries. The fact that countries like Pakistan and Indonesia have become important sending countries reflects Germany’s growing global appeal. Given that student flows from major sending countries like India are expected to swell, and given Germany’s keen interest in attracting more of these mobile students, academic mobility to the country is bound to increase in the years ahead.

However, while Germany’s marketing efforts, greater number of English-taught program offerings, and scholarship funding are effective measures that enhance Germany’s appeal, perhaps the biggest challenge for German stakeholders is to increase graduation rates and retain international students after they graduate. Since many international students enroll in English-taught programs, graduates often encounter a language barrier when they seek employment in Germany, while inadequate support and integration measures, as well as bureaucratic hurdles, continue to present challenges [35].

Some observers are therefore concerned that Germany is in danger of being an “educational transit country [76]” that spends public funds on educating international students without motivating these students to immigrate to Germany [77] and contribute to the country’s success. It remains to be seen if these concerns prove alarmist amid positive trends—according to a 2018 survey [78] of 4,339 international students in Germany, 69 percent of them intended to stay in Germany and look for work.

1. [79] The minimum salary is currently 53,600 euros, but workers in occupations with critical labor shortages like computer engineers or doctors are eligible if their jobs pay 41,808 euros.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of World Education Services (WES).