Carlos Monroy, Manager of Credential Examiners, Ryan McNally, Knowledge Management Specialist, and Stefan Trines, Research Editor, WENR

Introduction: An Education System Rocked by Political Change

Since the inauguration of right-wing president Jair Messias Bolsonaro in January 2019, public education in Latin America’s largest country has been under pressure. The new government has demanded the banishment of “ideologies of the left [2]” from classrooms and begun a defunding of higher education. Among the actual and proposed cuts was an announcement in May of this year to slash funding for Brazil’s federal higher education institutions by 30 percent—a measure that could affect close to 300 universities and institutes [3]. Allocations for scholarships [4] for graduate students and researchers were also cut, potentially jeopardizing funding for more than 80,000 students [5]. The government has stated that some of the funds would be redistributed to the school system, but a recent spending cut of about USD$87 million [6] targeted expenses in basic education such as schoolbooks as well.

Sometimes dubbed the “Trump of the tropics,” Bolsonaro is a former congressman, military officer, and outspoken admirer [8] of the Fifth Brazilian Republic, the military dictatorship that ruled Brazil from 1964 to 1985. He won Brazil’s presidential elections on a populist anti-establishment platform, vowing to rid Brazil of socialism and political correctness. He promised to crack down on rampant crime and corruption, reform the country’s ballooning pension system, liberalize the economy, lower taxes, and privatize state assets. Compared with those of countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Brazil’s government owns a large number of state-controlled enterprises [9].

Bolsonaro’s government, stacked with former military officers and economic liberals, upended the 15-year reign of Brazil’s center-left Worker’s Party and could bring sweeping changes to the world’s fourth-largest democracy—from the erosion of environmental protection standards [10]for the Amazon rainforest, to the attrition of democratic freedoms [11], or the realignment of the country’s foreign policies [12].

As for education, Bolsonaro’s spending cuts appear to be – at least in part – a politically motivated move to stymie political opposition. The new administration has specifically targeted sociology and philosophy departments [13]—an apparent attempt to rid universities of supposed leftist indoctrination. Beyond that, some observers have suggested that defunding education caters to the desires of segments of Brazil’s white upper classes to block “the access of the upwardly mobile, often nonwhite poor into elite spaces [14].”

Perhaps most controversial, Bolsonaro’s first education minister, Ricardo Vélez—sacked after only three months in office—pursued the politicization of Brazil’s school system by asking that schools film students singing the national anthem while being read Bolsonaro campaign slogans [15]. Vélez also proposed to rewrite textbooks to describe Brazil’s 1964 military coup as “a democratic regime by force which was necessary at the time [16].”

Bolsonaro’s policies encounter stiff resistance in Brazil. Massive student [17] and teacher protests [18] and the president’s declining popularity in opinion polls [19] reflect the widespread opposition. However, as Brazilian academics Marcelo Knobel and Fernanda Leal argued in a recent article [20], if the new government succeeds in implementing its policies, it could seriously harm Brazil’s higher education system and the country’s economic development. Given that Brazil’s educational attainment rates and tertiary enrollment ratios are below those of several other Latin American countries, it is critical that the nation of 211 million people expand access to higher education to enlarge its human capital base. Slashing spending for the tuition-free public universities, which include Brazil’s top research institutions, works against this objective and is likely to further shift enrollments to the country’s ubiquitous private universities, many of which are of lesser quality.

Structural Conditions and Constraints of Education in Brazil

Rich in natural resources, Brazil is a vast country that occupies half of South America’s land mass. It has the largest population of Catholic Christians in the world [21]—some 61 percent of the population are believers in the Catholic faith. Beyond that, it’s a heterogeneous nation with wide economic and fiscal disparities between its federal states. Its diverse population includes indigenous peoples, the descendants of African slaves, and European settlers. More than 150 languages [22] are spoken in the former Portuguese colony, although almost all Brazilians speak Portuguese.

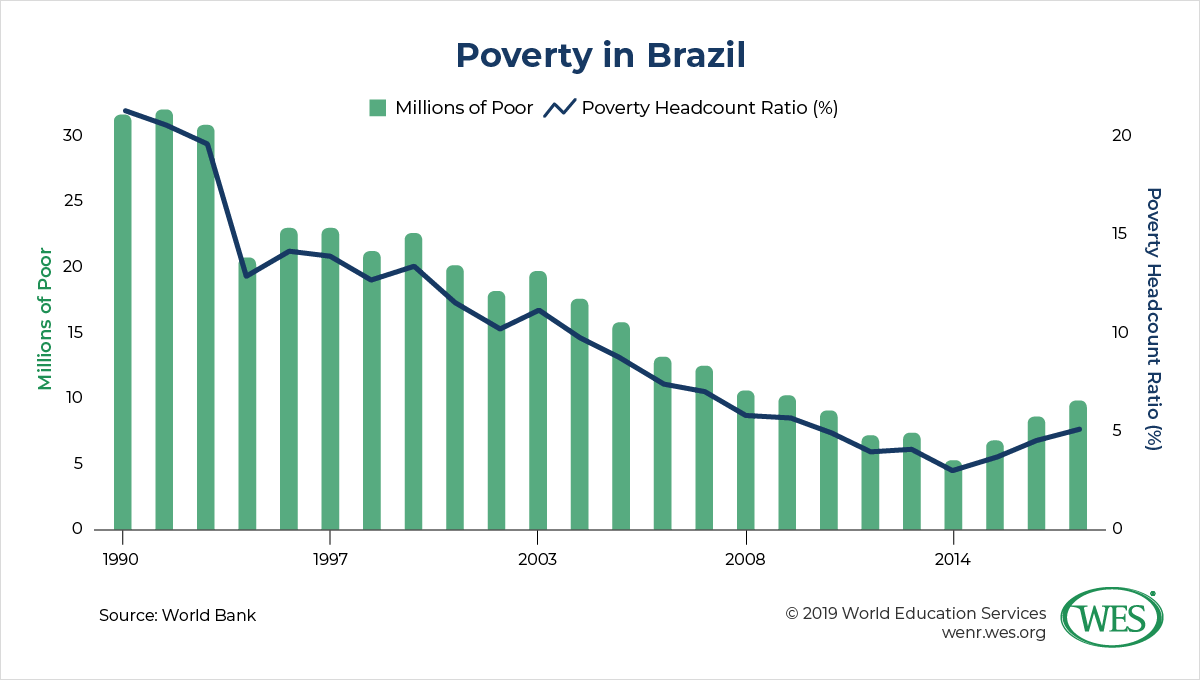

One of the so-called BRIC countries [23], Brazil experienced rapid economic growth in the 21st century. It is now an upper middle income country on the verge of becoming a developed industrialized economy. However, Brazil’s economic fortunes reversed in 2014 when, because of falling commodity prices [24] and high public [25] debt, among other problems, the country slid into its worst economic downturn since the 1930s. In 2015, the economy contracted by 3.8 percent and experienced another 3.6 percent drop [26] in economic output in 2016. The social impact of this crisis was profound: While Brazil made rapid progress in reducing wealth disparities and reduced the number of people living in extreme poverty from more than 20 million in 2003 to less than 6 million in 2014 [27], the recent recession has worsened the country’s Gini index and plunged an additional 6.3 million [27] people into poverty.

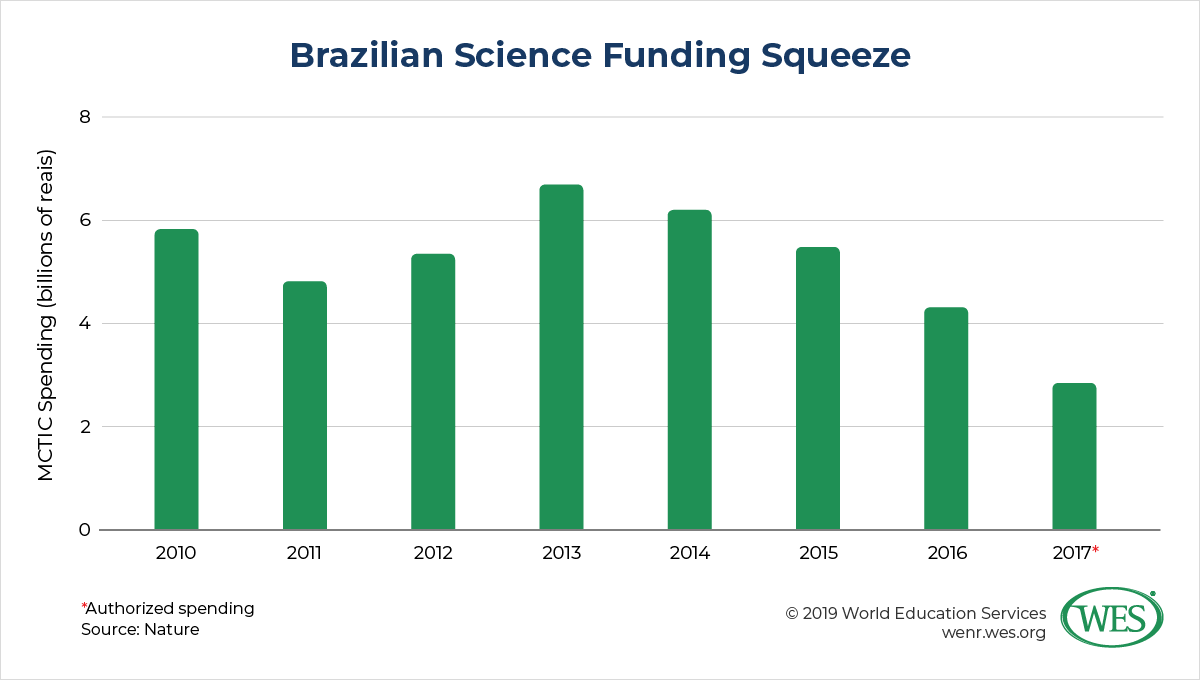

While the economy has since improved, the Brazilian government had to cut back on public expenditures, including spending on research and science. In 2016, the government capped budget increases for science at inflation rates for 20 years, effectively freezing spending for the next two decades. This freeze followed a decrease of Brazil’s science budget by more than 40 percent over the previous three years [29].

However, despite this fiscal crisis, public spending in tertiary institutions actually increased by 19 percent [30] between 2010 and 2016, before Bolsonaro’s recent cuts cast doubt on future higher education spending. Total education expenditures also increased with Brazil spending more on education as a percentage of its GDP (about 6 percent) “than countries like Argentina (5.3%), Colombia (4.7%), Chile (4.8%), Mexico (5.3%), and the US (5.4%). Some 80% of countries, including several developed countries, spend a lower percentage of their GDP on education [31].”

Since education is one of the main catalysts for lifting people out of poverty, adequate education spending is crucial to help boost social mobility. But despite its relatively high overall spending levels, Brazil spends less per elementary and secondary student than most OECD nations and its educational outcomes continue to fall short. For example, the World Economic Forum in 2017 ranked the quality of elementary education in Brazil 77th out of 130 countries [33] (behind Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Colombia, Peru, and Mexico). Likewise, Brazil ranked only 63rd out of 70 countries in the most recent 2015 OECD PISA study [34], in which it participates despite not being an OECD member state, making it one of the worst-performing countries in Latin America after Peru and the Dominican Republic. By some estimates, it could “take Brazil more than 260 years to reach the OECD average proficiency in reading and 75 years in mathematics [35].”

Great progress has been made in expanding access to elementary education, but dropout rates remain high. While the youth literacy rate has increased from 95 to 99 percent [36] since 2000 and nearly all Brazilian children are now enrolled in elementary schools, about 15 percent [37] of students drop out without graduating (as of 2015). Enrollment ratios in secondary and higher education are low as well: In 2014, the country’s “share of 25-34 year-olds with at least an upper secondary education … [was] below the OECD average (61%, compared to the OECD average of 83% [38]).”

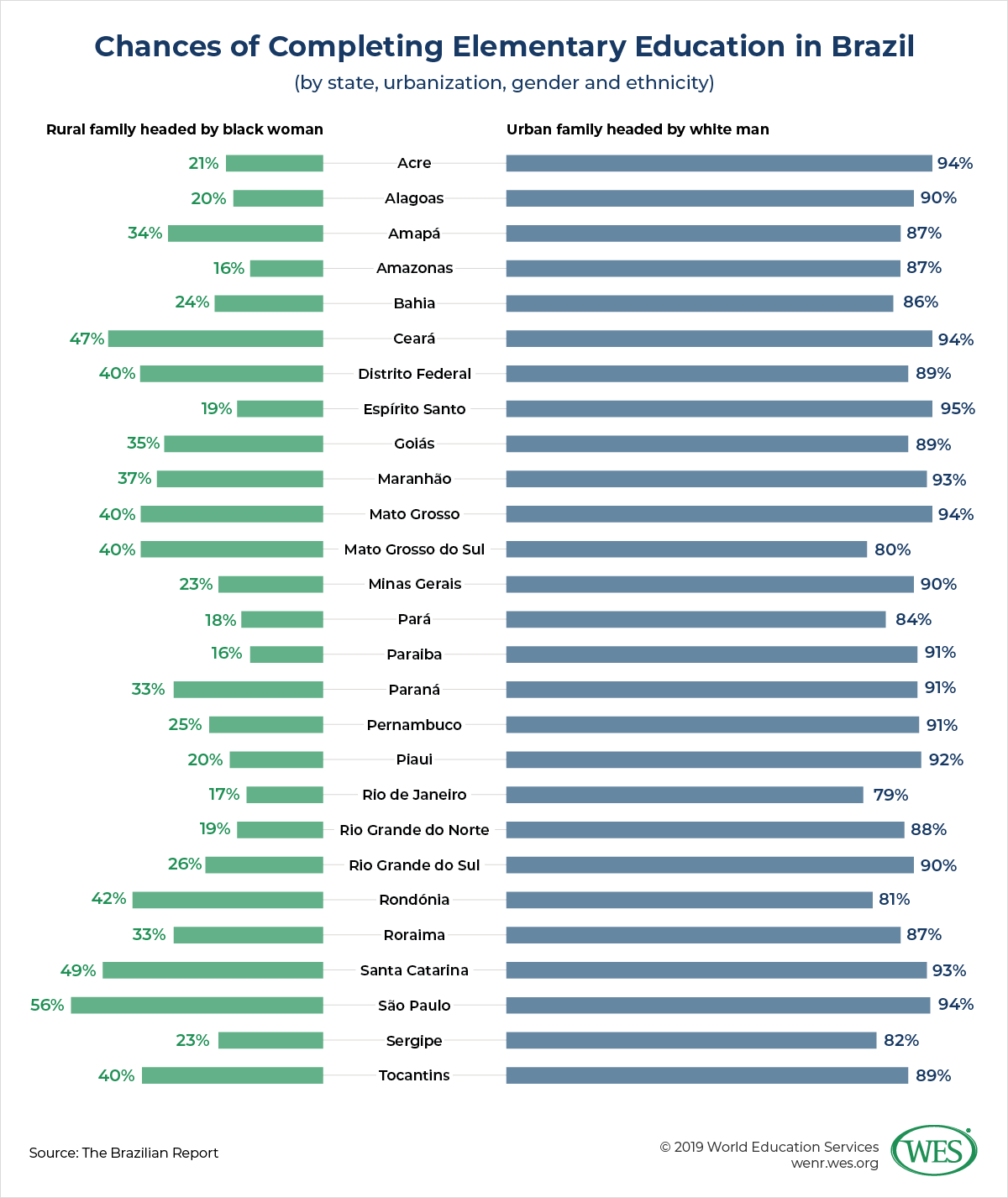

Brazilian education is characterized by wide disparities in resources, access, and quality based on geographic location, socioeconomic status, and ethnicity. To name some examples, the lower-secondary graduation rate in the metropolis of Sao Paolo stood at 93 percent in 2015, but did not exceed 63 percent [39] in the underdeveloped state of Alagoas. Upper-secondary completion rates ranged from 66 percent [40] in cities to 43 percent in rural areas. Higher education attendance was as high as 47 percent among the richest segments of Brazilian society, but only 5 percent [41] among the poorest. Whites have completed 2.5 more mean years of education than indigenous peoples. Private schools, which tend to outperform public schools in terms of learning outcomes, cost as much in fees as poor households earn in total income and are therefore mostly reserved for privileged elites [42].

These imbalances in education mirror the fact that Brazil is one of the world’s most unequal societies in general. Whereas the poorer half of the Brazilian population had an average monthly income of only USD$204 in 2019, the richest 10 percent of the population earned 10 times that (USD$2,463 on average), according to governmental household surveys [44]. The aid organization Oxfam International highlights these disparities with a stark statistic: “Brazil’s six richest men have the same wealth as [the] poorest 50 percent of the population; around 100 million people. The country’s richest 5 percent have the same income as the remaining 95 percent [45].” According to the organization, it will take Brazil “75 years to reach United Kingdom’s current level of income equality and almost 60 years to meet Spanish standards. Compared to its neighbors, Brazil is 35 years behind Uruguay and 30 behind Argentina.”

Outbound Student Mobility

Brazil is characterized by growing outbound student mobility, fueled in part by rising tertiary enrollments. As populous a country as it is, Brazil is expected to be among the top five countries worldwide in terms of total tertiary enrollments by 2035 [46], population aging [47] notwithstanding.

This increase in student enrollments enlarges the pool of potential international students from Brazil, the number of which has grown rapidly since the beginning of this century, even though the total percentage of Brazilian students going abroad is still small (0.7 percent of degree-seeking students in 2017 [48]). Consider that the number of Brazilian nationals enrolled in degree programs in other countries tripled over the last 16 years, from 19,200 in 2001 to 58,800 in 2017, according to UNESCO statistics [48]. Notably, there’s been a significant acceleration of student outflows in recent years. Between 2014 and 2017 alone, the number of Brazilian international students jumped by more than 15,000, or 38 percent.

This recent uptick comes despite inhibitive factors, such as the scaling back and eventual suspension of Brazil’s scholarship program for international study called “Science without Borders” (SWB, Ciência sem Fronteiras [49] in Portuguese). Started in 2011 [50], this massive government-sponsored program helped send close to 100,000 Brazilian students abroad before Brazil’s fiscal crisis resulted in steep cuts to the program in 2015, and its termination in 2017.

However, most mobile Brazilian students are self-funded [51], and many Brazilians are now able to afford an international education independent of scholarships. While Brazil’s recent recession thinned the ranks of its middle class by millions of people, more than half of the country’s population (113 million people) are currently considered middle class, 40 percent more than in 2003 [52].

Growing numbers of students from affluent households are incentivized to study abroad because of a shortage of high-quality graduate programs in Brazil and the highly selective admission quotas for these programs at top public universities. The slashing of public science budgets may, in fact, contribute to outbound mobility as more Brazilian students and researchers seek alternative opportunities [53] abroad. It should also be noted that Brazil’s government has replaced SWB with a smaller scholarship initiative [54] for graduate students and postdoctoral researchers, the so-called “More Science, More Development” (Mais Ciência, Mais Desenvolvimento) program.

Although funding shortages hinder internationalization initiatives at public HEIs, and Brazil is generally considered a relatively insular higher education system, transnational partnerships and joint research projects with foreign universities are becoming more common as well, helping to boost academic mobility.

Another major driver of outbound student flows from Brazil is surging demand for English language training (ELT). English language abilities in Brazil are still relatively underdeveloped with only an estimated 20 percent of Brazil’s rising middle class said to speak English [55] as of 2012. However, English is increasingly considered a coveted asset for employment [56] in a tight labor market, leading to greater demand for ELT training at private schools.

This demand also manifests itself in surging enrollments in ELT programs in other countries. By some accounts, the number of students enrolled in English language study courses abroad increased by as much as 600 percent [57] between 2003 and 2013 alone. Current data from the Brazilian Educational and Language Travel Association (Belta [58]) indicate that Brazilian enrollments in language training programs abroad increased by fully 20.5 percent in 2018 and reached a record high of 365,000 students [59], the vast majority of them studying English. These students’ top destination countries are Canada, the U.S., the U.K., Ireland, and Australia.

Destination Countries

Among degree-seeking Brazilian students, the top destination countries are neighboring Argentina and the U.S., accounting for around 21 percent of international enrollments each, followed by Portugal, Australia, France, and Canada (UNESCO data [60]). There’s been an increasing diversification [61] toward more affordable study destinations in recent years. The number of Brazilians studying for degrees in Argentina, for instance, jumped by 39 percent between 2016 and 2017, likely because the country offers Brazilians high-quality education at relatively low costs. As the British Council has noted [62], Argentina “has a well-established public higher education system with few fees (if any), no admissions exams and a globally respected level of quality. As such, it is not only a strong choice for those domestically but also for students regionally.”

The United States

Brazilian enrollments in the U.S. have fluctuated widely because of the SWB scholarship program, which mainly funded undergraduate students in STEM disciplines. After the program was launched, the number of Brazilian students in the country grew by 170 percent, from 8,777 in 2010/11 to 23,675 in 2014/15, according to the Open Doors data [63] of the Institute of International Education (IIE). When the program was scaled back, that number immediately dropped by 18 percent in 2015/16 and decreased by a further 32 percent in 2016/17 [64].

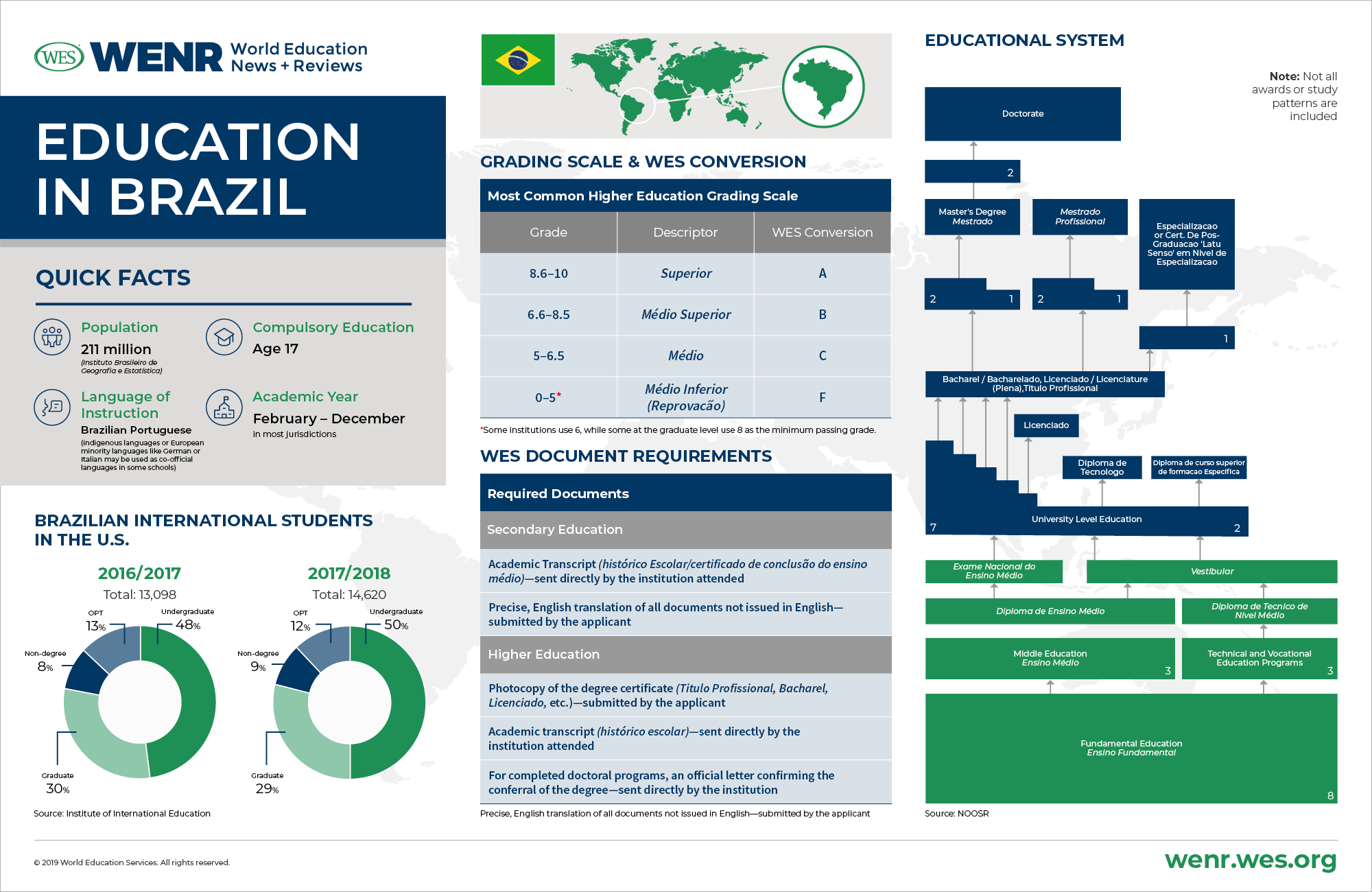

However, enrollments have recently rebounded at all levels of education and increased again by 12 percent in 2017/18 to 14,620 students, making Brazil the 10th-largest sending country of international students in the U.S. (down from sixth place in 2014/15, per IIE). While it remains to be seen how enrollment trends will evolve in the Trump era, the U.S. continues to be a popular study destination among Brazilians. Whereas the number of non-degree students tanked by as much as 83.5 percent in 2016/17, enrollments in graduate degree programs have been affected less. In fact, there are slightly more Brazilian graduate students in the U.S. now than in the peak year of 2014/15. Half of all Brazilian students in the U.S. presently study in undergraduate programs, 29 percent in graduate programs, 9 percent in non-degree programs, and 12 percent pursue Optional Practical Training. The most popular fields of study among Brazilians are business and engineering.

Portugal

Given the two countries’ historical ties and shared language, Portugal is a major destination country not only for Brazilian students but for Brazilian migrants in general, making up Portugal’s largest immigrant community. The number of Brazilian degree-seeking students in Portugal spiked by 177 percent between 2010 and 2017, going from 2,801 to 7,764, according to UNESCO [48]. Data collected by the Portuguese government put this number even higher, at 12,200 [65], which means that 15 percent of all international students—the largest group in Portugal—are Brazilians.

Beyond the shared language, Portugal is an attractive destination for Brazilians because it’s easier to get admitted into Portuguese HEIs than into public universities in Brazil [65]. Visas are relatively easy to obtain, and Brazil’s national university exams are directly accepted for admission by 30 Portuguese universities [65]. While Portuguese universities charge tuition fees, Portugal is a comparatively affordable country by European standards, and tuition fees are below those charged by private HEIs in Brazil.

Australia

Australia is another country that has seen a rapid increase in student inflows from Brazil in recent years. In fact, the uptick in Brazilian enrollments has been so drastic that Brazil is now the fourth-largest sending country [66] of international students in Australia and Australia’s most important source country in Latin America. According to Australian government data, the number of Brazilian student enrollments in the country more than tripled between 2007 and 2019, from 9,863 to 33,601 [67]. It should be noted that most of these enrollments are not in tertiary education, but in non-tertiary vocational programs (56 percent) and ELT (37 percent [68]). The opportunity to work while studying, and the availability of further employment opportunities and migration pathways are part of what draws Brazilian students to Australia, especially in light of the economic downturn and high unemployment in their own country.

Canada

The picture in Canada looks similar. According to government data [69], the number of Brazilian students in the country surged from 2,720 in 2010 to 13,835 in 2018—an increase of 409 percent. Brazilian student enrollments have risen simultaneous to the Canadian government’s increasing immigration quotas and making it easier for international students to become permanent residents [70] and citizens [71] in recent years. Another driver of student inflows is the fact that Canada overtook the U.S. as the most popular ELT destination among Brazilians a few years ago. According to observers like Belta, Canada’s rising prominence as an ELT destination is owed, at least partially, to the country’s comparative cost advantage [61] vis-à-vis the U.S., as well as more favorable currency exchange rates [72]. Doubts [73] about the U.S. under President Trump and his anti-immigration policies are likely to push more students to Canada as well.

Inbound Student Mobility

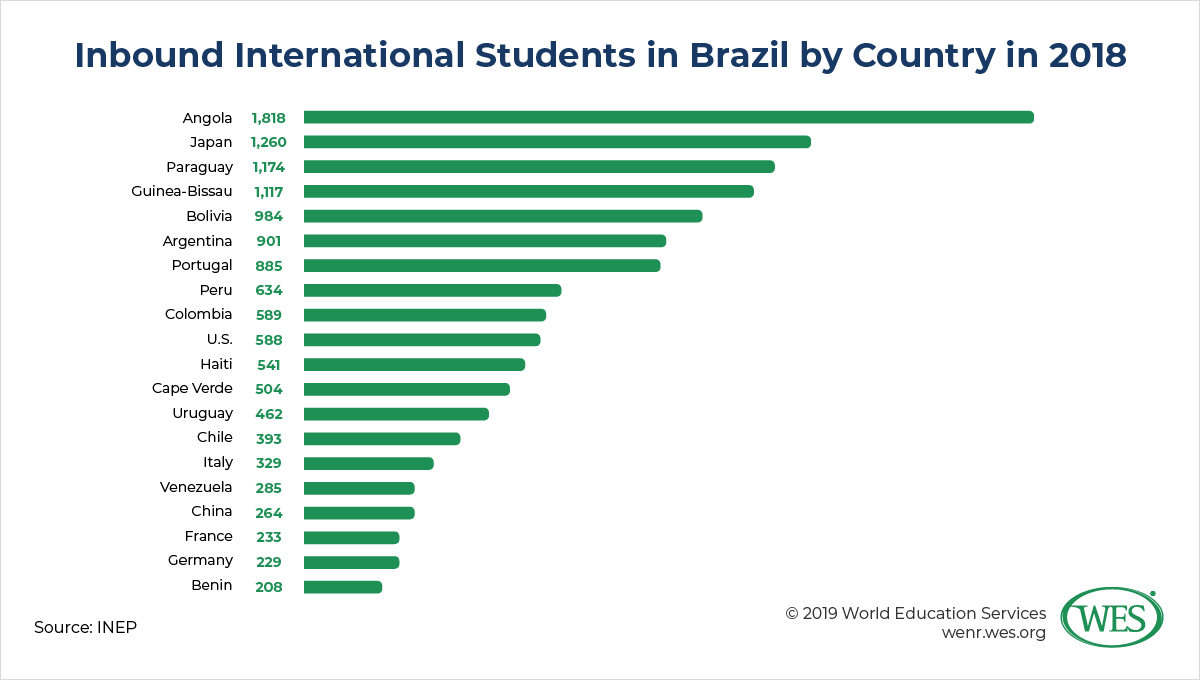

Brazil is not a major destination country for students from other nations. Compared with neighboring Argentina, where there were 88,873 international degree-seeking students in 2017, only 20,671 international students were enrolled in degree programs at Brazilian HEIs despite Brazil having a population nearly five times that of Argentina’s. Only 0.24 percent of all degree students in Brazil are international, as per UNESCO—a low percentage by international standards.

According to Brazilian government data, Angola is the biggest sending country of international students to Brazil, presumably because students from the former Portuguese colony can study in Brazil in Portuguese, the official language of Angola. The two countries are historically connected—millions of Afro-Brazilians are of Angolan ancestry. There’s also a sizable number of students from other former West African Portuguese colonies like Guinea Bissau and Cape Verde, reflecting the fact that Brazil has become an increasingly important alternative to Europe for students and migrants from this part of the world. [74]

Interestingly, Japanese are the second-largest group of international students in Brazil, likely because Brazil, notably Sao Paolo, is home to the largest population of Japanese people outside of Japan [76]. Japanese Brazilians are the biggest immigrant group in the country. Neighboring South American countries like Paraguay, Argentina, and Peru are top sending countries as well.

A Brief History of Education in Brazil

Education in Brazil was historically influenced by the Catholic church, which introduced religious education during the colonial era (1500 to 1822). The Jesuit missionaries who arrived in the 16th century played an important role in shaping Brazilian society. Their schools followed European models of education with the aim of increasing Portuguese language literacy among indigenous populations to convert them to Catholicism. Enslaved black people, on the other hand, were excluded from education [77]. Overall, the system remained highly elitist during the colonial period. Despite the establishment of elementary schools in all Brazilian provinces, only 10 percent [78] of the school-age population was enrolled in elementary education when Brazil became independent in 1822.

The first public universities in Brazil were established at the beginning of the 20th century, followed by the creation of the Ministry of Education and Public Health in 1930. At this point, the Brazilian state began to slowly establish tighter control over education and to develop a modern mass education system. Brazil’s 1934 constitution enshrined education as a basic right of all Brazilian citizens. The first overarching education laws were adopted in 1961 and 1971 [79]; they introduced compulsory elementary education until grade eight before the military dictatorship imposed Portuguese as the language of instruction nationwide in 1971.

Since then, the Brazilian system has grown rapidly, first through the expansion of the elementary and secondary school systems, followed by a speedy growth of higher education enrollments that overburdened the public university system and eventually triggered the large-scale privatization of tertiary education. As Brazilian political scientists Elizabeth Balbachevsky and Helena Sampaio described the process [80], the “enlargement of the secondary school sector and new alternatives for adult education brought to public universities many qualified candidates who could not be accommodated. To respond to this pressure, the government relaxed constraints over the private sector. …. Since the late 1960s, the private sector has converted itself into a demand-driven sector, absorbing the bulk of the demand for access and protecting the public sector from the most disruptive effects of massification.”

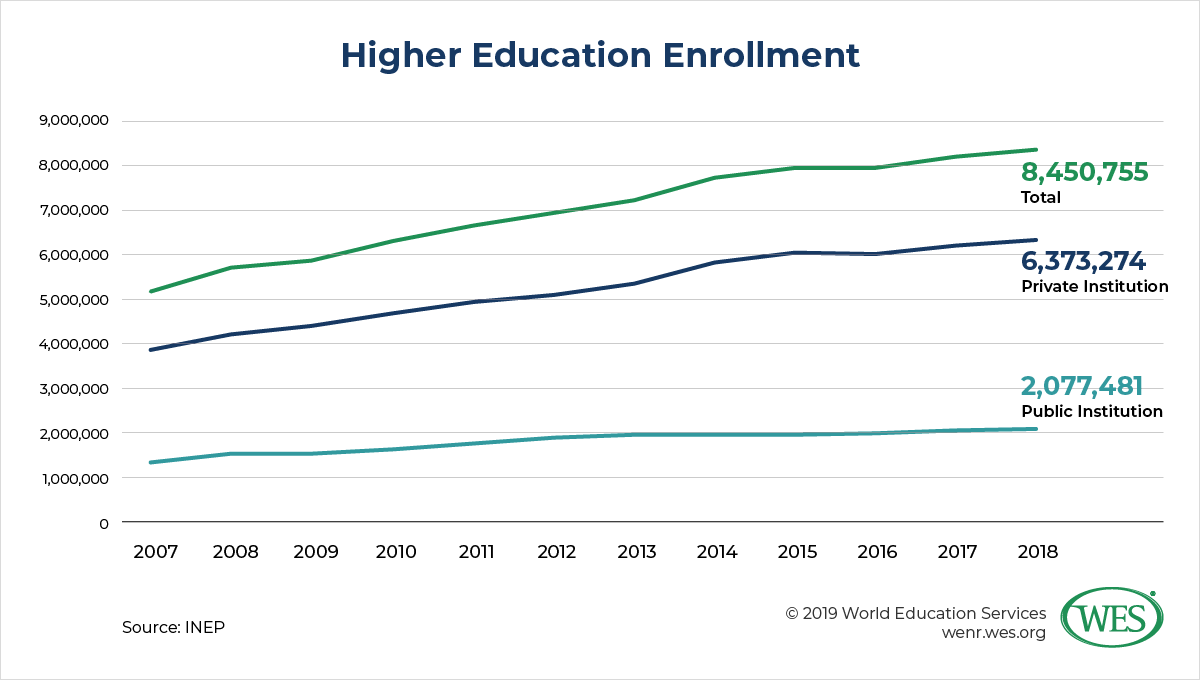

To quantify the growth of the Brazilian system, the number of tertiary students more than quadrupled from 1.75 million in 1995 to 8.45 million in 201 [81]8. However, as noted before, participation rates in upper-secondary and higher education are still held back by social inequalities and regional disparities, so that the percentage of the Brazilian population with tertiary attainment continues to be low by regional standards, despite the rapid expansion. According to the OECD, only 16 percent of the population aged 25 to 34 had completed higher education in 2017 compared with 22 percent in Mexico, 37 percent in Chile, and 28 percent in Colombia [82].

Administration of the Education System

The Federative Republic of Brazil is a federation of 26 states and a self-governing federal district which contains the capital city, Brasilia. While Brazil witnessed periods of rigid centralization, notably under its military governments, the political system has been increasingly decentralized since the late 1980s, so that Brazil is now a decentralized country with relatively strong state governments.

According to Brazil’s current education law [83], education is the shared responsibility of the federal, state, and municipal governments. Whereas the national government sets overall education policies and is responsible for higher education, school education is administered locally by the state and city governments, which have a fair amount of autonomy (within federal guidelines). The core school curriculum, for example, is set nationally, but states have the right to adapt it to suit local needs.

The main federal supervisory authority in the school system is the National Education Council (Conselho Nacional de Educação), an agency of the Ministry of Education (MOE). In addition, all Brazilian states have their own education councils which oversee the schools in their jurisdictions and administer examinations. City governments may grant recognition to private institutions at the early childhood education level, whereas private elementary and secondary schools are generally authorized by state governments. Public HEIs can be established by federal, state, or municipal legislation, but the national government is the only authority that can grant recognition to private higher education institutions.

The main federal oversight body in tertiary education is the Department of Higher Education (Secretaria de Educação Superior, SESU) of the MOE. It formulates higher education policies, develops curricular guidelines, and accredits institutions and study programs. The National Education Council, on the other hand, defines the minimum number of classroom instruction hours and general guidelines for all levels of education and fields of study [84].

In terms of funding, states and municipalities are constitutionally mandated to spend at least one quarter of their tax revenues on education while the federal government is required to spend at least 18 percent of its tax income [85]. In addition, there are spending targets for specific sectors. For example, a 1996 constitutional amendment required states and municipalities to spend at least 60 percent [86] of their education budget on elementary education—a requirement that helped make elementary education universal in Brazil. A new 14-year program established in 2006 (FUNDEB [87]) seeks to further increase participation rates in early childhood, elementary, and secondary education. FUNDEB’s increased spending levels are designed to broaden access to education in rural areas, in underserved regions, and among indigenous populations [88].

The Structure of the Education System

Brazil’s education law defines two main levels of education: basic education (educação básica) and higher education (educação superior). Each level of education is further subdivided as follows:

Educação Básica (Basic Education)

-

- Educação Infantil (early childhood education): Ages 4–5

- Ensino Fundamental (elementary education): Grades 1–9

- Ensino Médio (secondary education): Grades 10–12

Educação Superior (Higher Education)

-

- Cursos seqüenciais (short term/ vocational programs)

- Graduação (post-secondary, undergraduate, and first professional degrees)

- Pós-graduação (graduate/postgraduate education)

- Extensão (continuing education)

Basic Education

Compulsory basic education, provided free of charge at public schools, has in recent years been extended to early childhood and secondary education. While actual realities often look different, all Brazilian children are now officially required to attend two years of early childhood education and stay in school until the age of 17 (previously 14). Combined, the basic education cycle comprises 14 years.

The national curriculum (base nacional comum [89]) sets the core content and modalities of education for the entire country. At present, each academic year includes a minimum of 800 hours of classroom instruction at each level, but the system is currently being reformed to increase the number of hours in secondary education (see below). Three-quarters of school curricula consists of nationally mandated courses, which are then complemented with content relevant to local society and culture, or other special local needs.

While local governments can set their own academic calendars (as long as school is in session for at least 200 days a year), the school year runs from February to December in most jurisdictions. It is typically divided by a winter break in July and another break in December. Some states may have varying calendars. The state of Roraima in northern Brazil, for instance, has a shorter school year that lasts from March to December, but compensates with Saturday classes [90].

The language of instruction in public schools is usually Brazilian Portuguese, although schools in some regions may use co-official languages, such as indigenous Amerindian languages or European minority languages like German or Italian.

Early Childhood Education

Participation in early childhood education in Brazil was low until recently, especially among low income households. Several states were financially ill-prepared to provide this form of education across the board. However, the introduction of mandatory pre-school education and investments in infrastructure and human resources have helped to almost double enrollments in early childhood education, from 4.6 million in 1999 to 8.7 million [91] in 2018. While participation is not universal, 90 percent of relevant age cohorts currently enroll in kindergartens or day care centers—a relatively high percentage by OECD standards [92].

Early childhood education lasts two years (ages four and five) and is provided mostly by public schools: 77 percent of children were enrolled in public institutions in 2018 [93]. Most of these institutions are administered by city and municipal governments—states and the federal government play only a marginal role in this sector. Private schools at this level have become more closely regulated [94]and now follow recently developed national curriculum guidelines.

Elementary Education (Ensino Fundamental)

Elementary education begins at the age of six and lasts nine years. It’s divided into two cycles: Ensino fundamental I (years one to five) and ensino fundamental II (years six to nine). In most states, each cohort of pupils is taught by a single teacher in the first cycle, whereas there are different teachers for different subjects in the second cycle. While national legislation requires that public schools provide 800 hours of instruction per year, private institutions often supplement the official curriculum and provide 1,000 or more hours of instruction [95].

The curriculum includes Portuguese, mathematics, history, geography, natural sciences, arts, and physical education from grade one to grade five. Since 2016, English is a required subject beginning in grade six—a change from previous years when the states could decide which foreign language to teach, if any. Upon completion of grade nine, pupils receive a certificate of completion of elementary education (certificado de conclusão do ensino fundamental). There are no final graduation examinations.

While the language of instruction is Portuguese, indigenous etnias have the constitutionally enshrined right to use their native languages and their own learning methods. In practice, only a few states and cities have implemented curricula that incorporate native languages, in some cases along with German and/or Italian. Religion must be offered by law, but it is an elective, depending on the jurisdiction.

Participation in elementary education is universal – 99 percent of the relevant age cohort entered the first grade in 2018. However, while dropout rates are close to zero in developed states like Santa Catarina, Mato Grosso, and Pernambuco, the situation in some north and northeastern states is problematic. The overall graduation rate for elementary education was only 76 percent in the state of Sergipe and 77 percent in the state of Bahia in 2014/2015, according to government statistics [91]. As noted, stark disparities in educational outcomes exist between private schools in industrialized states and public schools in impoverished rural neighborhoods [96].

Overall, elementary school enrollments have decreased drastically in recent years due to rapidly declining fertility rates—the number births per 1,000 people dropped from 18.7 in 2008 to 14.1 in 2018 [97]. There were 27.2 million [96] elementary students in Brazil in 2018 compared with close to 36 million in 1998.

Secondary Education (Ensino Médio)

Secondary education lasts three years (grades 10 to 12), although some vocational programs and programs for adult students can vary in length in each state. It’s provided free of charge at public schools and has been compulsory since 2013. Most students who completed the ensino fundamental can access secondary education without sitting for an entrance examination, although some competitive schools require exams for admission.

Schooling is offered at instituições de ensino médio (general academic) and instituições de ensino técnico (technical schools), as well as military schools and teacher training schools (discussed further below). Many students attend evening classes. Private schools tend to be better equipped to provide higher quality education, but play only a relatively minor role; 86 percent [36] of students were enrolled in public institutions in 2017.

There’s a small but growing number of international English-medium schools [98] in major cities catering to expats and wealthy elites. These typically teach foreign curricula (U.S., British, International Baccalaureate). Some of these institutions charge fees from USD$1,800 to USD$3,000 per month [99]. But despite these astronomical fees, many schools are said to have long waiting lists [100].

The national core curriculum (parte comum) includes the following mandatory subjects: Portuguese, English, an additonal elective foreign language, arts, physical education, mathematics, physics, chemistry, biology, history, geography, philosophy and social studies. Until recently, a minimum of 75 percent of the curriculum had to contain instruction in these subjects, whereas the rest of the curriculum (parte diversificada) was determined by the states or municipalities. However, reforms under way since 2017 will increase the percentage of locally tailored courses to 60 percent [101].

The final credential awarded by regular general academic schools is the Certificado de Conclusão do Ensino Médio, sometimes also called the Diploma de Nível Médio or Diploma de Ensino Médio (secondary education diploma). Persons who dropped out of school have the option of acquiring a secondary school leaving certification by sitting for an equivalency exam called the National Exam for Certification of Youth and Adult Skills (ENCCJE [102]).

There is also a National Examination of Secondary Education (ENEM) organized by the MOE. However, sitting for the ENEM [103] exam is not mandatory for graduation, and students who do not wish to go on to higher education don’t have to take it. Given in November each year and comprising 180 multiple choice questions, the exam was originally introduced to evaluate student performance to measure the quality of individual schools and secondary education in Brazil at large. In addition, it’s now used for admission purposes by public and many private HEIs, as well as to determine the eligibility of students for government higher education scholarships, such as the PROUNI [104] and FIES [105] programs. The ENEM is said to be the biggest nationwide test in the world after China’s massive Gaokao examination—5.5 million [106] students registered to sit for the ENEM in 2018. Besides representing students enrolled in grade 12, this number includes independent external students and younger students (treineros) that sit for the exam for practice and self-evaluation purposes.

Secondary Enrollment Trends and Reforms

Total enrollments in secondary education have declined in recent years, just as they have in basic education, because of shrinking fertility rates. There were 7.7 million secondary students in 2018 compared with 8.3 million in 2009 [91]. Despite progress in increasing participation rates, Brazil still has one of the largest shares of adults without upper secondary education compared with adults in OECD countries. As of 2018, only “69% of 15-19 year-olds” were “enrolled in any level of education, well below the OECD average … of 85% [107].”

By some estimates, 2.8 million Brazilian students [108] between the ages of 15 and 17 abandon school each year because of financial constraints, the need to work, poor academic preparedness, teen pregnancy, or lack of interest or transportation [109]. As at all levels of Brazilian education, participation and dropout rates are much more favorable in industrialized urban areas than in more rural, peripheral regions.1 [110]

Race in particular is strongly correlated with academic success and poverty. Three in four [111] people living in extreme poverty in Brazil have black or brown skin. Blacks not only have lower attainment rates [111] at all levels of education, but also higher murder and incarceration rates [112] than whites. Given this prevalence of structural racism, it’s unlikely that universal enrollment in secondary education will become a reality in Brazil anytime soon.

To lower dropout rates, Brazil is currently implementing a range of reforms. A 2016 education reform [113] extended the number of mandatory hours of classroom instruction at public schools from 800 to 1,400 per year to give students more time to master the curriculum—a change that will be gradually phased in, in two stages: 1,000 hours as of 2017, and 1,400 hours beginning in 2022 [114].

In addition, students will get more freedom to tailor curricula to their interests: At least 60 percent of secondary curricula will be made up of specialized subjects and electives, including competency-based vocational subjects [101]. There will be greater flexibility to change the format of lessons to include internships, labs, or projects. Online education is permissible if it does not exceed 20 percent of programs’ instructional hours (30 percent in the case of programs offered at night). The reforms are still being finalized but will be gradually implemented in each state. The hope is that the new curricula will stimulate critical thinking and be more engaging for students.

Secondary Technical and Vocational Education

Vocational and technical education in Brazil has undergone various changes under different governments. It was first introduced in the early 20th century, partially as an effort to bring more people into the labor force. Vocational education then became a prominent feature of Brazilian education in 1971, when the military government enacted a new education law [79] that required all secondary schools to transform their curricula to incorporate vocational training—an attempt to rationalize schooling and tie it more directly to industrialization and labor market needs.

These changes were abolished in the 1990s, and academic and vocational secondary education became mostly separate tracks. Most recently, the Brazilian government again mandated the inclusion of elective vocational subjects by 2022 [115] in all school curricula. However, despite these changes, separate secondary vocational programs continue to exist in Brazil, most of them offered by public and private schools overseen by state governments.

These schools offer programs at two different levels: At the basic level, there are employment-geared certificate programs without formal admission requirements. These programs are of varying program lengths, from a few months to a few years; they usually don’t include much general education and conclude with the award of a qualificação profissional (professional qualification), a credential that provides access to employment and upper-secondary technical education.

In addition, there are higher level secondary programs that require the certificado de conclusão do ensino fundamental for admission and lead to the award of the diploma de técnico de nível médio (intermediate level technician diploma), a credential that provides access to higher education. These programs are typically three to four years in length (800 to 1,200 hours per year); they generally combine education in vocational subjects with a general core curriculum that comprises Portuguese, a foreign language, mathematics, biology, chemistry, physics, geography, and physical education. Many programs include an industrial internship. There are also some shorter program options (two years or less) for individuals who already completed one or two years of general secondary education (concominante), as well as for upper-secondary graduates (subsequente).

Since 2008, the MOE publishes a “national catalog of technical programs [116]” that defines the program regulations and learning outcomes of the available vocational subject specializations. The latest 2014 catalog [117] includes 227 types of programs grouped in 13 broad areas of specialization, including communication technology, natural resources (agriculture etc.), industrial technology, health-related fields, tourism and hospitality, and military specializations.

While overall enrollments in secondary vocational programs have been on an upward trajectory for much of the past decade, the percentage of secondary students in vocational programs is still relatively small: In 2018, there were 1.9 million [93] students enrolled in technical programs compared with 7.7 million in general programs. However, the Brazilian government has made it a priority to boost enrollments in vocational programs and to increase the level of articulation between general and vocational programs [118].

Higher Education

Unlike in other Latin America countries like Mexico, where the Spanish created the first local university as far back as 1551, universities were late arrivals in Brazil. During colonial rule, very few HEIs were established under the authority of the Portuguese royal family [119]. Instead, most elite Brazilian families sent their sons to the Universidade de Coimbra in Portugal, where upon graduating, they returned to Brazil to enter high public offices or political careers [120]. Between 1889 and 1918, 56 new colleges academies and faculties were eventually established in Brazil, the majority of them being non-profit private institutions [121] specialized in fields like medicine or law. But it was not until 1920 that the first full-fledged public university, the Universidade do Rio de Janeiro, was founded [122].2 [123]

Soon after, several public universities sprung up in various Brazilian states, most of them made up of smaller existing mono-specialized institutions (faculties). Autonomous and tuition-free, these universities increased access to higher education for students from middle class households, rather than just catering to wealthy elites [122]. As such, the new universities provided a platform for academic and social debates that eventfully spawned Brazil’s National Union of Students (União Nacional dos Estudantes—UNE). A democratic student organization founded in 1937, UNE extended across several universities and was an important vehicle for effecting social change [124]. The union’s political activities eventually culminated in massive student protests in 1968 that caused Brazil’s military government to implement a major university reform, before it repressed and dissolved the UNE. Today, UNE is again an important leftist organization with five million members that advocates equal access to higher education, among other causes.

The 1968 university reform laid the groundwork for the current structure of Brazilian higher education. It modernized public universities and introduced important changes, such the development and national standardization of graduate programs. Crucially, it allowed for the establishment of independent private HEIs, ushering in a literal explosion of the number of these institutions. Within just two years after the reform, the number of private providers doubled and enrollments in private institutions began to outpace enrollments in public [125] HEIs [126]. The most rapid expansion of the private sector happened after 1996, when the Brazilian parliament passed legislation [127] that allowed private HEIs to be for-profit in nature.

By 2019, private institutions represented a staggering 88 percent of all Brazilian HEIs, or 2,238 institutions [128] in total. Between 2000 and 2018 alone, the number of private HEIS increased by 1,234, or approximately 69 per year. While there are some religious, predominantly Catholic, and philanthropic non-profit universities, 70 percent [129] of private HEIs are run for profit. This includes Kroton Educacional [130], an institution said to be the world’s largest for-profit education provider by market capitalization. It enrolls some 900,000 undergraduate students [131] and operates 125 institutions in 18 Brazilian states and 83 cities [130]. Plans by Kroton Educacional to become even larger were stymied in 2017 when authorities blocked the company from merging with Estácio, the second-largest for-profit education company in Brazil. Had the merger gone through, the new company would have enrolled nearly a quarter of all Brazilian undergraduate students [132]. In general, Brazil’s higher education system is in constant flux due to frequent acquisitions and mergers of private HEIs.

By comparison, the number of public HEIs has grown only slowly, by just 123 over the two decades [134]. This means that for every public institution in Brazil, there are now more than seven private institutions. In 2018, public HEIs were able to only offer 835,569 undergraduate seats while private HEIs had over 12 million opens slots (94 percent [135] of all available seats). Some 75 percent of all tertiary students in Brazil were consequently enrolled in private institutions in 2018 [135].

Differences Between Public and Private HEIs

Competition for the limited number of open seats at public institutions is fierce. Not only provide public universities tuition-free undergraduate education and offer a much broader variety of programs, they are also consistently ranked highest in terms of quality, according to the General Index of Courses (Índice Geral de Cursos, IGC), an education quality indicator established by the MOE. (See the section on quality assurance below.)

Government-funded research universities are also ranked highest in international university rankings. The top four universities in the current 2020 Times Higher Education World University Ranking [136], for instance, are the public University of São Paulo (ranked at position 251-300 out of 1,400 universities worldwide), the University of Campinas (501-600), the Federal University of Minas Gerais (601-800) and the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (601-800). The top Brazilian institutions in the current QS World University Rankings [137], likewise, are all public institutions.

In a reflection of Brazil’s regional disparities, most of Brazil’s top institutions are concentrated in the southeast and northeast regions of the country, even though federal universities exist all over Brazil. As per the most recent IGC ranking of 2,000 HEIs released in December 2018 [138], nearly half of the top 30 ranked HEIs are in the state of Sao Paulo alone.

Only 1.6 percent of all HEIs achieved the maximum score of 5 in the ranking [139], most of them public. Only four private institutions achieved the top score: the non-profit institutions Escola de Administracao de Empresas de Sao Paulo and the Fundacao Tecnico Educacional Souza Marques, as well as two for-profit institutions called Faculdade Legale and Faculdade São Leopoldo Mandic.

Contributing to qualitative differences between public and private HEIs is the circumstance that private institutions mostly don’t focus on research and tend to specialize on programs with low operating costs that don’t require laboratories or highly paid professors, such as business or law programs. Whereas around 59 percent of instructors at public HEIs hold doctoral degrees, that percentage stood at only 18 percent at private faculties in 2017 [140]. Private institutions rely on part-time instructors to a large degree.

Tuition at private HEIs can vary drastically depending on the area of specialization, but these institutions are generally expensive, costing between R$7,800 and R$40,200 (US$1,880 and US$9,690) per year [141]. To put this in context, the average nominal monthly household income per capita in Brazil was USD$400, in 2016, according to government statistics [142].

Despite these high costs, private HEIs are predominantly attended by students from socially less privileged households, whereas public HEIs mainly enroll students with a better socioeconomic background: White students from affluent families who graduated from private secondary schools generally score highest in competitive university entrance examinations [143]. These students tend to specialize in areas that lead to higher salaries upon graduating, like engineering and medicine [139].

There are several policy measures in place intended to rectify such imbalances. For example, there are federal student loan programs, such as the Financiamento Estudantil no Ensino Superior (FIES), as well the ProUni program, which gives tax exemptions to private HEIs if they offer tuition assistance to students from low income households. In 2014, 22 percent of all students at private HEIs participated in these programs with 50 percent of them identifying as black or mixed race [144]. Former president Dilma Roussef in 2012 signed affirmative action legislation (lei de cotas) that created a quota system for underrepresented groups [145] at federal universities. However, President Bolsonaro, who has openly opposed racial quotas, will have the ability to revise the law in 2022 [146].

Types of HEIs

HEIs in Brazil are generally organized in three main categories, all of which encompass public and private institutions:

Faculdades (faculties): Specialized institutions that only offer programs in one or two fields of study. Most of them are private for-profit providers that only offer undergraduate programs with no or little focus on research, although some may offer graduate programs as well. There are also integrated faculties (faculdades integradas), which are groups of faculties that offer a limited range of programs under one umbrella and management structure while still being smaller than universities. Faculdades exist under several different names, such as escola superior or centro de ensino superior.

All private HEIs must initially be constituted as faculties before they can broaden their scope and operate as university-level institutions: To open new campuses, increase enrollments, or become a university, private faculties must be rated positively each accreditation cycle. Public HEIs, by contrast, can be established as universities from the outset.

Compared to university-level institutions, faculties have less autonomy: They require additional authorization for new program offerings, so that most faculties don’t apply for change in status and remain constituted as mono-specialized institutions. It should also be noted that most faculties don’t have standalone degree-granting authority—their degrees need to be approved and registered by public universities. This approval is noted on the back of the degree certificate. That said, since 2017 some private HEIs with sufficiently high ratings in Brazil’s accreditation process have been authorized to autonomously award their own degrees.3 [147]

2,068 HEIs in Brazil, or close to 82 percent of all institutions, were were classified as faculties in 2018. However, in what is testimony to the smaller size of these institutions, they only enrolled about 22 percent [128] of all tertiary students. The vast majority of them are private.

Centros Universitários (university centers) are primarily undergraduate institutions that – unlike universities – concentrate on teaching rather than research, even though several of them offer more professionally oriented graduate programs. These institutions offer a broader range of study programs than faculties and have greater autonomy. They have control over aspects like course content and can offer new undergraduate programs or increase their number of seats without formal authorization. Unlike faculties, they can issue and register diplomas for their own programs. In 2018, there were only 230 centros universitarios in Brazil, enrolling about 23 percent [128] of students. 94 percent of these institutions are private.

Universidades (universities) are full-fledged multi-disciplinary research universities that provide the entire range of study programs up to doctoral degrees. Universities are largely autonomous in terms of their program offerings and course content. Unlike faculties and university centers, which are initially accredited for three years, universities are given an initial accreditation period of five years. In 2018, there were 199 universities enrolling 53 percent [128] of tertiary students. About half of them are public, including 63 federal universities (universidades federales), 40 state universities (universidades estaduales) and 4 municipal universities (universidades municipiales).

In addition to these three types of HEIs, there are Federal Institutes of Education, Science and Technology (Institutos Federais de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia – IFs) and Federal Centers of Technological Education (Centros Federais de Educação Tecnológica – CEFETs) that provide applied technical education from the basic education level to graduate education. These institutions are directly overseen by federal or state governments and concentrate on fields like engineering, as well as teacher training in physics, chemistry, mathematics and biology. The 40 IFs have several campuses located in each of the 27 Brazilian states [148]. CEFTEs are being phased out with in favor of IFs with only two of them remaining. Together, these institutions enroll about 2.3 percent of the undergraduate student population [128].

Quality Assurance and Accreditation

The quality assurance procedures in Brazilian higher education are complex. There are separate evaluation mechanisms for undergraduate and graduate programs, based on which the MOE authorizes institutions to operate, respectively to offer specific programs. All HEIs in Brazil, public and private, must seek accreditation by the MOE and apply for re-accreditation (recredenciamento) in specific intervals. For private HEIs this process is essential for continued operation while for public institutions it’s more of a formality. Universities and university centers are re-accredited every eight to ten years, while faculties must seek reaccreditation at least every five years [149].

Quality Review of Undergraduate Programs

Newly established undergraduate programs need to have recognition (reconhecimento) and undergo an external review by the National Institute for Educational Studies and Research (INEP), a body of the MOE. This initial review takes place once 50 percent of teaching hours have been completed (often in the second or third year of the program.). If recognition is not achieved, programs need to close and their students are transferred to other institutions [150].

Once undergraduate programs have been recognized, they are continuously evaluated. This process involves a mandatory written test given to students upon graduation. Called the National Examination of Student Performance (Exame Nacional de Desempenho dos Estudantes, or ENADE [151]), this test includes a general segment that is common across all disciplines along with major-specific questions. The final “ENADE score” (Conceito ENADE) is then combined with other criteria like personal student evaluations to calculate a final “Preliminary Course Score” (Conceito Preliminar de Curso, or CPC) every three years. The CPC is expressed on a scale of one to five and determines if program recognition is renewed: While the recognition of programs that were rated three or higher is automatically renewed, programs with a score below three must undergo additional on-site inspections by INEP and may lose recognition. (For an in-depth review of this process, see this OECD publication. [152]

Quality Review of Graduate Programs

One special feature of Brazilian higher education is a separate system of external quality assurance for graduate programs conducted by the Foundation for the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – CAPES [153]), overseen by the MOE. All new master’s and doctoral programs – collectively called stricto-sensu programs – are assessed by a panel of academic peers and subsequently re-evaluated every four years. “The results of this evaluation – attributed through scores on a scale of one to seven – allow programmes to continue operating or, in case of poor performance, lead to withdrawal of funds and recognition [152]” of the programs they offer. “This effectively means programs that fail the CAPES evaluation are forced to close [152].” A score of three or higher is the threshold score for approval. To promote quality, higher scores are often tied to greater public funding [154].

Institutional Ranking (Índice Geral de Cursos – IGC)

As mentioned, Brazilian HEIs are ranked using the IGC indicator. In a nutshell, the IGC score is made up of the average of the last three years of CPC and CAPES scores weighted by the number of students enrolled in evaluated programs. In addition, criteria like the quality of institutions’ infrastructure and teaching staff are also included. The IGC score is expressed on a five-point scale. Scores of one and two are considered unsatisfactory by the MOE, potentially subjecting HEIs to academic restrictions until the next assessment. However, few institutions fail to muster the official criteria: Only 10 HEIs received the lowest IGC score of one in 2018—one university and nine faculties; 14 percent of all institutions received a score of two [155].

University Admissions

Admission to public institutions in Brazil is incredibly competitive for most programs. In 2015, some 1.1 million applicants to federal universities competed over just 55,571 available slots, which means that there was only one seat for every 20 candidates [156]. At top institutions that ratio is even worse: 95,000 applicants vied for a mere 3,200 available seats at Universidade Estadual de Campinas in 2019 [157]. The situation is so dire that empty university seats in Brazil’s peripheral Northeastern region are being filled with students from São Paulo, which means that many local students no longer have access to these schools. [158]

While many prestigious public universities used to have their own entrance examinations, known as vestibular, admission at federal universities is since 2009 solely based on the ENEM national high school examination, a change that caused other HEIs, both public and private, to follow suit. Other than federal universities, Brazilian HEIs are free to set their own admission standards, but more and more institutions use the ENEM as the principal admissions criterion each year.

In addition, federal authorities in 2010 introduced a digital platform called the Unified Selection System (Sistema Unificado de Selecao –SISU [159]) to streamline admission to public HEIs and grant scholarships. Students who have passed the ENEM register on the SISU website and choose their top two schools and programs. From there, the system allocates students based on their ENEM scores. Required ENEM scores vary by institution and program [160]. Grade cutoffs in popular disciplines like medicine, law, or engineering tend to be highest. Although most private HEIs now also rely on the ENEM, they may use various criteria, including their own admission tests, but they have generally much less stringent requirements than public institutions. If they use the ENEM, they usually require lower scores than public HEIs.

Credit System and Grading Scales

The Brazilian government mandates a set number of hours, or carga horária, for undergraduate programs. The carga horária comprises in-classroom learning time, and practicum training courses or activities, including internships. The number of required hours varies by program. For example, 2,400 hours are required for music, history, design, and social science programs, whereas business programs require 3,000 hours, and longer professional programs in medicine must comprise at least 7,200 hours [161]

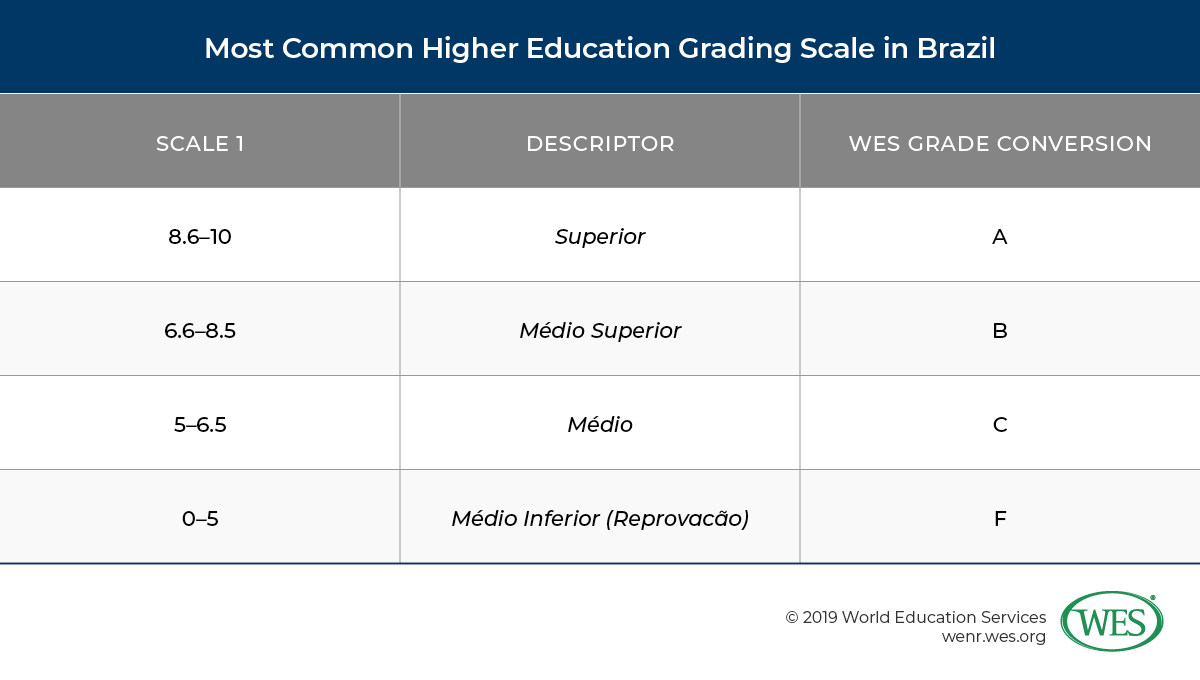

There is no nationally standardized credit system, but several institutions define one credit as 15 contact hours per semester, while some institutions may define one credit as 20 contact hours per week There is no uniform higher education grading scale either, but the most common grading scale is 0-10 with 5 as the minimum passing grade. Some institutions use 6, while some at the graduate level use 8 as the minimum passing grade. A-D grading scales may also be used by some HEIs. Most transcripts list a key to the specific grading scale used.

The Higher Education Degree Structure

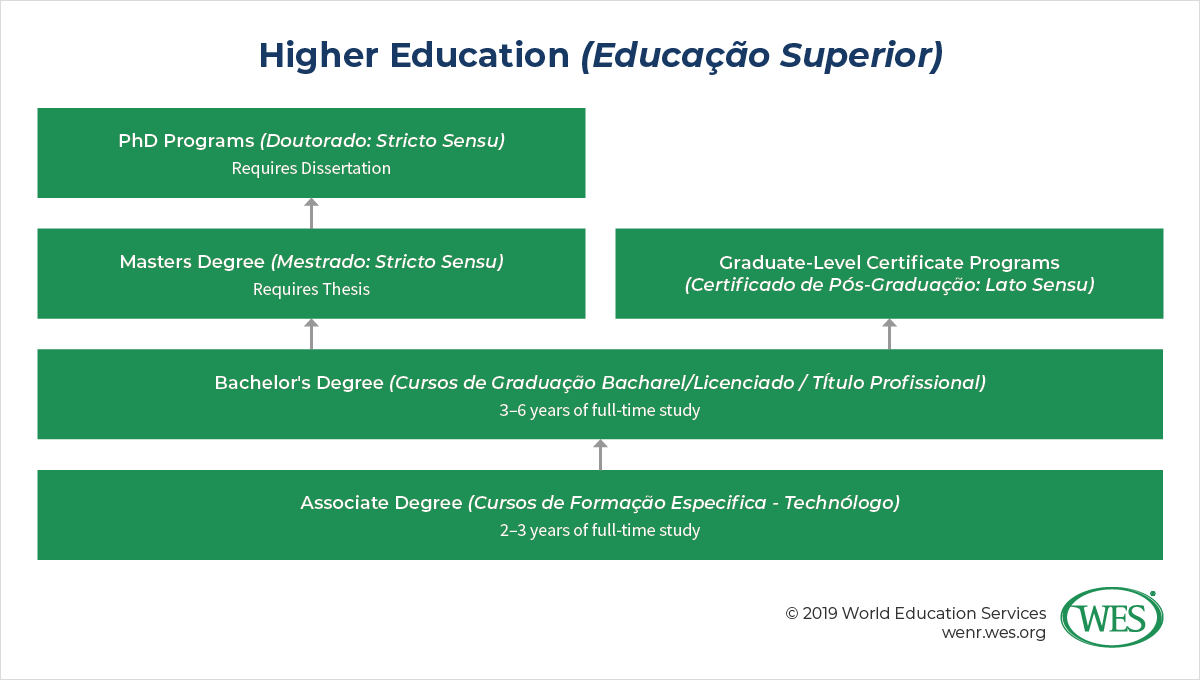

Degrees awarded in Brazil are organized in two main categories. The first, graduacao, includes shorter associate degree-type qualifications (tecnólogos), teaching degrees (licenciaturas), bachelor’s degrees (bachareis), and professional degrees (titulos profissionais). The second category is pos-graduacao, which includes shorter, graduate certificates, and then master’s and doctoral degrees.

Undergraduate Education

There were 8.45 million [128] undergraduate students enrolled in Brazil in 2018. About 68 percent of them were enrolled in bacharel programs, while 19 and 13 percent, respectively, attended licenciatura and teconologo programs. Tecnologo programs experienced the greatest growth in enrollments over the past ten years.

Tecnólogos

Curso Superior de Tecnologia (higher technologist) programs are between two and three years in length and are entered after upper-secondary school; they lead to the tecnólogo degree, usually after a minimum carga horaria of 1,600 hours for two-year programs and 2,000 and 2,400 hours, respectively, for two-and-a-half- and three-year programs. Tecnólogo programs are offered by all types of HEIs in Brazil, although private faculties dominate this sector. Curricula are applied and geared toward employment. They typically include an internship. However, unlike in other Latin American countries that have similar education systems, tecnólogo degrees nevertheless allow access to graduate-level programs that lead to a professional master’s degree (mestrado professional).

Tecnólogo programs are offered in a variety of specializations, but business is the most popular [164] major by far. About one million students enrolled in technology degree programs in 2018, almost half of them in distance education mode. Distance education enrollments in tecnólogo programs have surged by a staggering 586 percent since 2007 [129].

Distance Education

Given the growing demand for education and the increasing use of the internet to deliver learning content, distance education in Brazil is thriving. In 1996, HEIs were allowed to augment existing face-to-face programs with undergraduate and lato sensu graduate programs delivered via distance mode. In 2017, regulations were then further eased to allow HEIs to operate as pure distance education providers. This was followed by a change in 2019 that granted HEIs the right to also offer mestrados and doutorados through distance education.

In 2018, 24 percent [128] of all undergraduate students were enrolled in distance education, 92 percent of them at private HEIs. In 2018, available distance education seats outnumbered the number of available slots in traditional teacher training programs for the first time [128]. Yet, even further growth of distance education is expected: Private institutions are now allowed to establish up to 250 distance learning centers per year in multiple locations, without each facility having to be inspected separately by INEP. While individual distance study programs must comply with the same accreditation standards as traditional programs, the rapid growth of distance education has nevertheless raised concerns about adequate quality assurance. On the other hand, distance learning helps expand urgently needed capacities and allows underserved students in rural and remote areas to access higher education.

Bacharel

The bacharel is the standard first cycle tertiary degree in Brazil. Programs are between three and six years in length and require a set number of minimum hours, ranging from 2,400 to 7,200. Programs in business administration, accounting, computer science, and economics typically take four years of study, whereas programs in architecture, law, engineering, and psychology take five years. Professional programs in medicine last six years [161]. Students who previously earned a tecnólogo degree may be exempted from specific courses, but there is no formal, lateral pathway structure between the two programs.

Curricula typically include a small general education component, usually at the onset of the program, as well as a final project, such as a thesis, and a mandatory internship (not exceeding 20 percent of the study load). Programs in disciplines like accounting, law, or medicine require a final graduation examination. Graduates in professional disciplines are bestowed a formal Titulos Profissionais (professional title), such as Titulos de Médico (title of medical doctor) and Titulos de Engenheiro (title of engineer). After graduation, students can continue their education in both lato sensu and stricto sensu programs, as well as doctoral programs in some cases.

Licenciatura (Teacher Education)

The licenciatura is a pedagogical degree that allows graduates to teach basic education, from early childhood to upper-secondary education. It’s a three- to four-year program that requires 2,800 hours of study at minimum, including a supervised teaching internship of at least 300 hours. Alternatively, holders of undergraduate degrees in another discipline can complete a one-year “top-up” program. The licenciatura gives earners access to lato sensu and stricto sensu graduate programs.4 [165]

About 19 percent of Brazilian undergraduate students were enrolled in licentiatura programs in 2018, mostly at private institutions, and about 71 percent [128] of them were women. Interestingly, more than 60 percent of students who started licentiatura programs that year studied in distance education mode. This trend toward distance learning for teacher education has raised questions about quality in a profession that relies so heavily on practical training, especially since face-to-face learners outperform distance learners in the ENDA exams [166]. Neighboring countries like Chile and Peru recently banned distance teacher education, and critics are demanding that Brazil do the same to improve quality standards [166].

Postgraduate Education

Graduate programs in Brazil are divided into two distinct groups: Lato-sensu (wide sense) and stricto-sensu (strict sense) programs. Lato-sensu programs, which are also called especializacao programs, are professionally oriented terminal programs geared toward specialized employment. They are considered complementary qualifications that help students prepare for the labor market. Stricto-sensu programs, on the other hand, are academic research qualifications (master, doctoral) that are subject to tighter regulations. Whereas stricto sensu programs must be accredited by CAPES, lato-sensu programs do not. Graduates of lato-sensu programs cannot receive exemptions in stricto sensu master’s programs.

Especialização (pos-graduação latu sensu)

Independent from the approval procedures for academic qualifications, postgraduate specialization programs can be fairly easily set up and are more flexible in terms of curricula, although there are certain restrictions, such as the requirement that at least 30 percent [167] (50 percent until 2018) of the faculty of HEIs offering these programs hold a master’s or doctoral degree. Between 1998 and 2009, non-academic institutions (companies) could obtain special accreditation to offer specialization programs—a fact that led to a mushrooming of companies offering these programs. While this practice was stopped [168] in 2009, recent legislative changes [167] from 2018 again allow non-academic institutions to offer specialization programs, if under tighter restrictions.

The courses themselves must have a duration of at least 360 hours and take anywhere from nine to 24 months to complete. They can be offered via distance education but must include face-to-face examinations or the defense of a final project. Otherwise, there’s no final thesis required as in the case of master’s programs. Admission requires a tecnólogo or bacharel.

Specialization certificates awarded in the field of business administration may indicate the title MBA or Master of Business Administration. However, this qualification is not a master’s degree in the Brazilian sense of the term [169].

Mestrado (pos-graduação stricto sensu)

The mestrado is an academic research degree that was not introduced in Brazil until the 1960s. Admission at competitive institutions requires a bacharel or licenciatura, entrance examinations, and additional foreign language tests, but several HEIs grant admission based on the lower tecnólogo degree. Most programs last two years and require 30 credits or more. They conclude with the defense of a thesis and comprehensive exams.

In addition to academic programs, there’s the mestrado professional, a more applied program introduced in the 1990s that prepares students for skilled employment. While generally considered equivalent to the standard mestraodo, these credentials do not offer access to doctoral programs.

Master’s degree programs have grown in popularity quickly in Brazil in recent years, most notably the professional programs. Between 2009 and 2017, enrollments in mestrado professional programs increased by 270 percent, while enrollments in academic mestrado programs grew by 39 percent [170].

Doutorado

The doutorado is an advanced research degree and Brazil’s highest academic qualification. Admission generally requires the mestrado and demonstrated ability in two foreign languages, but exceptional students may sometimes be admitted based on the bacharel, in which case the program lasts longer.

Programs involve at least one year of coursework (30 credits) and the defense of a dissertation. While it is technically possible to complete the program in two years, most students take four.

The number of doctoral programs offered by Brazilian HEIs has grown exponentially in recent years, and enrollments have surged by 93 percent to 112,000 between 2009 and 2017 [170]. Even so, only 0.2 percent [92] of Brazilians have attained a doctorate.

WES Documentation Requirements

Secondary Education

- Academic transcript (histórico Escolar/certificado de conclusão do ensino médio)—sent directly by the institution attended

- Precise, English translation of all documents not issued in English—submitted by the applicant

Higher Education

- Photocopy of the degree certificate (Titulo Profissional, Bacharel, Licenciado, etc.)—submitted by the applicant

- Academic transcript (histórico escolar)—sent directly by the institution attended

- For completed doctoral programs, an official letter confirming the conferral of the degree—sent directly by the institution

- Precise, English translation of all documents not issued in English—submitted by the applicant

Sample Documents

Click here [171] for a PDF file of the academic documents referred to below.

- Certificado de Conclusão do Ensino Médio

- Técnico de Nível Médio

- Tecnóloga

- Bacharel

- Licenciada

- Título de Médica

- Certificado de Especialização/ Pós-Graduação – Lato Sensu

- Mestre

- Doutora

1. [172] Data provided by the Observatório de Educacão [173] show that public schools in the states of Pernambuco, Espírito Santo, São Paulo, and Distrito Federal had dropout rates below 5 percent, while the states of Sergipe, Paraíba, Pará, and Alagoas had dropout rates over 14 percent in 2016. Dropout rates in low income districts stood at 11 percent, but at only 3 percent in affluent districts.

2. [174] It should be noted that the university’s polytechnic school already existed in the form of the Real Academia de Artilharia, Fortificação e Desenho” (Royal Academy of Artillery, Fortification and Design), founded in 1792.

3. [175] See article 27 of Decreto No 9.235 [176], article 50 of Portaria Normativa No 23 [177], as well as articles 6, 19-22 of Portaria No 1095 [178].

4. [179] Note that previously there were separate two-year licenciatura curta programs that qualified individuals to teach at the elementary level, and three-year licenciatura plena programs for secondary teachers.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of World Education Services (WES).