Eleonora Fallwickl, Credential Analyst Team Lead, WES, Ryan McNally, Knowledge Manager, WES, Chris Mackie, Editor, WENR

Nicknamed “Africa in miniature,” the Republic of Cameroon exhibits much of the rich geographic and cultural diversity of the continent. Vast tropical rain forests, volcanic mountains, desert landscapes, and more reflect the vegetation and climatic variety of Africa. Throughout the country, a young, growing population enlivens city streets and rural hamlets, while a cross section of the continent’s major ethnicities, languages, and religions endow Cameroon’s inhabitants with a strong sense of sub-national solidarity and meaning.

But Cameroon also shares many of the continent’s challenges. Persistent economic weakness, growing inequality, political authoritarianism, and rampant corruption cloud the country’s future, while its quickly growing population threatens to overwhelm its social services.

Education in the republic is no different. As in the rest of the continent, Cameroon’s education system has achieved impressive results since the end of the colonial era, increasing literacy rates and extending free elementary education to nearly all of its growing youth population. But issues remain. Quality concerns and corruption continue to plague most levels of the education system, while access to secondary and higher education remains out of reach for many of the country’s most indigent communities.

Improving the education system will be key to Cameroon’s social and economic development. But the republic faces a far greater and more immediate obstacle. As in much of the rest of the continent, social fissures inherited from an age of colonial rule threaten not only the state of the country’s education system, but also the prosperity and well-being of its people.

Colonial Divisions and the Birth of the Anglophone Crisis

This rift was formed during a period of divided colonial rule. Following the end of World War I, the newly created League of Nations transferred control of the territory of today’s Cameroon from the German Empire, which had claimed Kamerun as its colony since 1884, to two of the victorious Allied powers: France and the United Kingdom. To accommodate joint rule, the territory was divided into two League of Nations mandates [3], with France ruling most of modern Cameroon, and the U.K. ruling just the western fifth, today’s Northwest and Southwest regions.

For the next 40 years, the trajectories of the two mandated territories, known as French Cameroun and British Cameroons, diverged sharply. Within the territories under their control, French and British colonial administrators established political and social institutions modeled on the very different institutions of their home countries. They also favored and promoted the spread of their native languages in political administration and, although to different degrees, in the slowly expanding formal education sector.

Colonial administrators also took different approaches to economic development [5] in their two mandates. The French made significant investments in agriculture, industry, and infrastructure aimed at increasing exports of primary products such as cacao, coffee, and bananas, to Metropolitan France. The British largely neglected their new colony, focusing their attention instead on its far larger northern neighbor, the Colony and Protectorate of Nigeria. Greater French involvement meant that by the end of the colonial era, French Cameroun had a “much higher gross national product per capita [6], higher education levels, better health care, and better infrastructure than British Cameroons.” French Cameroun also had four times the population and ten times the area [3] of the British Cameroons. These disparities would eventually allow Francophone regions to dominate government and administration [3] when the nation became unified.

The diverging trajectories of the two mandates began to converge in the early 1960s. In 1960, French Cameroun declared its independence, followed by British Cameroons a year later. In a 1961 plebiscite held in British Cameroons, voters opted to federate with what had been French Cameroun, creating the Federal Republic of Cameroon.1 [7] The Federal Republic’s 1961 constitution [8] split Cameroon into two states, Anglophone West Cameroon and Francophone East Cameroon, each retaining significant political power and possessing its own prime minister and legislature. It also guaranteed the cultural autonomy of each region.

But Cameroon’s experimentation with federalism did not last long. After banning all political parties but his own, Cameroon’s first leader, President Ahmadou Ahidjo, who ruled from 1960 to 1982, ended the federation in 1972, replacing it with a unitary state. The move concentrated power in the Francophone capital, Yaoundé, politically sidelining minority Anglophone Cameroonians. His successor, Paul Biya (1982 to present), like himself from one of the country’s French-speaking regions, took further steps [9] to centralize power in Francophone regions and stifle Anglophone cultural independence. In 1984, he changed the name of the country to that used by independent French Cameroun prior to unification, the Republic of Cameroon, and removed from the country’s flag one of its two stars, which together had symbolized the equal union of Anglophone and Francophone Cameroon. The combined impact of growing political exclusion and cultural erasure sparked outrage, and prompted the first call, but not the last, for the creation of an autonomous Anglophone state, the Republic of Ambazonia.

Tensions between Anglophone and Francophone regions have simmered ever since. In 2016, they boiled over, as demonstrations, led [10] in large part by students and scholars protesting political underrepresentation, cultural repression, and government favoritism toward French speakers, erupted in the Northwest and Southwest regions before being violently suppressed [11] by government forces. In late 2017, the government declared war [12] on Ambazonia nationalists.

Education has proved a flashpoint in the conflict. The Anglophone-based Cameroon Teachers Trade Union (CATTU) presented [10] the central government with a list of grievances, including higher rates of admission of Francophone students into professional and technical schools, accusations of doctoring admissions conducted in Yaoundé for Francophone students applying to the Anglophone region’s two main universities, and the appointment of Francophone teachers lacking a command of English to Anglophone schools. CATTU even requested that the 1998 Law on the Orientation of Education, the guiding legal framework for education in Cameroon, be eliminated.

The conflict, known as the Anglophone Crisis, has had a devastating impact on the people of Cameroon. It has claimed the lives of more than 4,000 civilians [13] and displaced more than 750,000 [14] in the affected regions, forcing them to seek refuge in other parts of the country or in neighboring Nigeria. Both sides have been accused of war crimes [15].

These tensions have placed enormous stress on the country’s education system. By late 2019, UNICEF reported that 855,000 children [16] in Northwest and Southwest Cameroon were still out of school, some for nearly three years [17]. More than 80 percent of schools in the two regions have been shuttered; 74 schools were destroyed [18].

Displaced families have been moved to refugee camps where it is not uncommon to see classroom sizes of more than 200 students. Adding to the strain in the camps are the nearly 450,000 refugees Cameroon has taken in from the Central African Republic and Nigeria, according to data from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees [19] (UNHCR).

Violence in other regions of the country has also had an impact on the country’s schoolchildren. Since 2014, attacks in northern Cameroon launched by the terrorist organization Boko Haram have led to the closure of hundreds of schools. Boko Haram, often interpreted to mean “Western education is a sin [20],” routinely targets schools, killing and kidnapping schoolchildren.

The situation in Cameroon’s Anglophone regions remains volatile. Until recently, Paul Biya, Cameroon’s octogenarian president and Africa’s second-longest ruling head of state [21], had largely ignored the crisis. Only in late 2020 did he make significant concessions, signing a devolution bill that would allow for regional elections [22] for the first time in Cameroon’s history. Elected members will sit on regional councils, which will exercise jurisdiction over certain areas of governance, including budgeting, justice, and education. But opposition parties were not impressed, choosing to boycott the elections [23]. Unsurprisingly, Biya’s party dominated the elections, even in the Anglophone regions.

Cameroon Today and Tomorrow

Despite domestic political challenges, Cameroon’s economy is a regional leader. The country’s gross domestic product [24] (GDP) has grown steadily since the mid-1990s and is today the largest of the six states [25] making up the Central African Economic and Monetary Community [26] (CEMAC). However, it trails its non-CEMAC neighbors, Nigeria and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Cameroon’s economy faces significant challenges, including volatility. Its heavy dependence on the sale of primary products [27] abroad leaves it vulnerable to notoriously unstable global prices. The economy is also ravaged by corruption. In 1998 [28], Transparency International (TI) ranked Cameroon as the most corrupt country in the world. The situation has improved only marginally since. TI’s latest Corruption Perceptions Index ranked Cameroon 149 out of 200 countries [29].

The population’s rapid expansion has also neutralized many of the benefits of the country’s steady economic growth. While Cameroon’s GDP has grown by nearly half [24] over the past 10 years, its per capita GDP [30] has barely budged, growing by less than a fifth over the same period.

As a result of these challenges, Cameroon’s population remains mostly low income, especially in remote regions—more than half [31] of rural Cameroonians lived below the poverty line in 2014, compared with less than one in ten in urban areas. Infrastructure in rural areas is also poor. In 2018, while 93 percent [32] of urban Cameroonians had access to electricity, less than a quarter [33] (23 percent) of those in rural areas did.

International Student Mobility

Cameroon’s unique geopolitical, economic, and educational conditions have had contrary effects on international student flows, driving significant numbers of domestic students overseas, while attracting sizable contingents of international students to its universities. Today, Cameroon is both one of sub-Saharan Africa’s largest sources of international students, and one of its most popular destinations for internationally mobile students. And its future could be even brighter. Leveraged effectively, its rapidly growing population and bilingual education system could be a dynamic force in international education.

Outbound Mobility

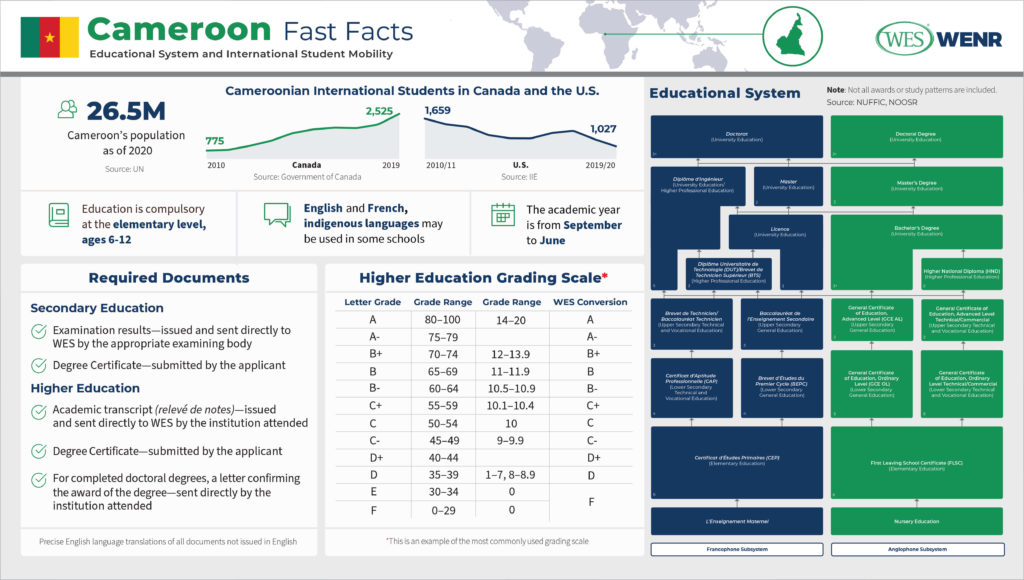

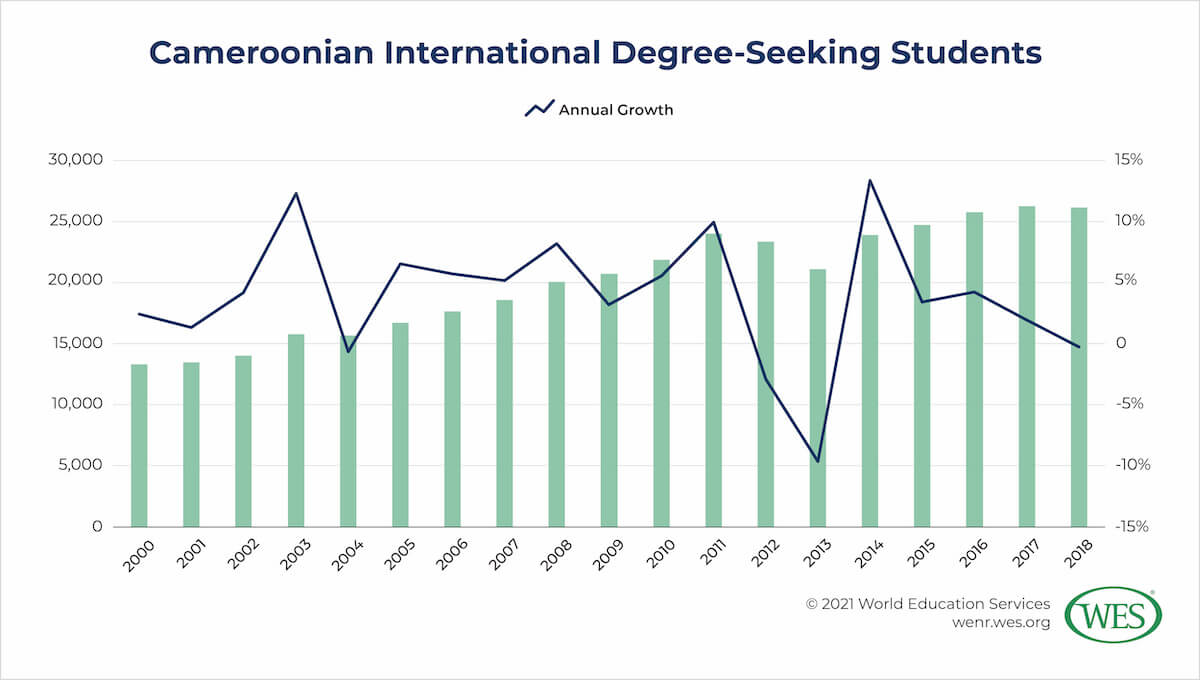

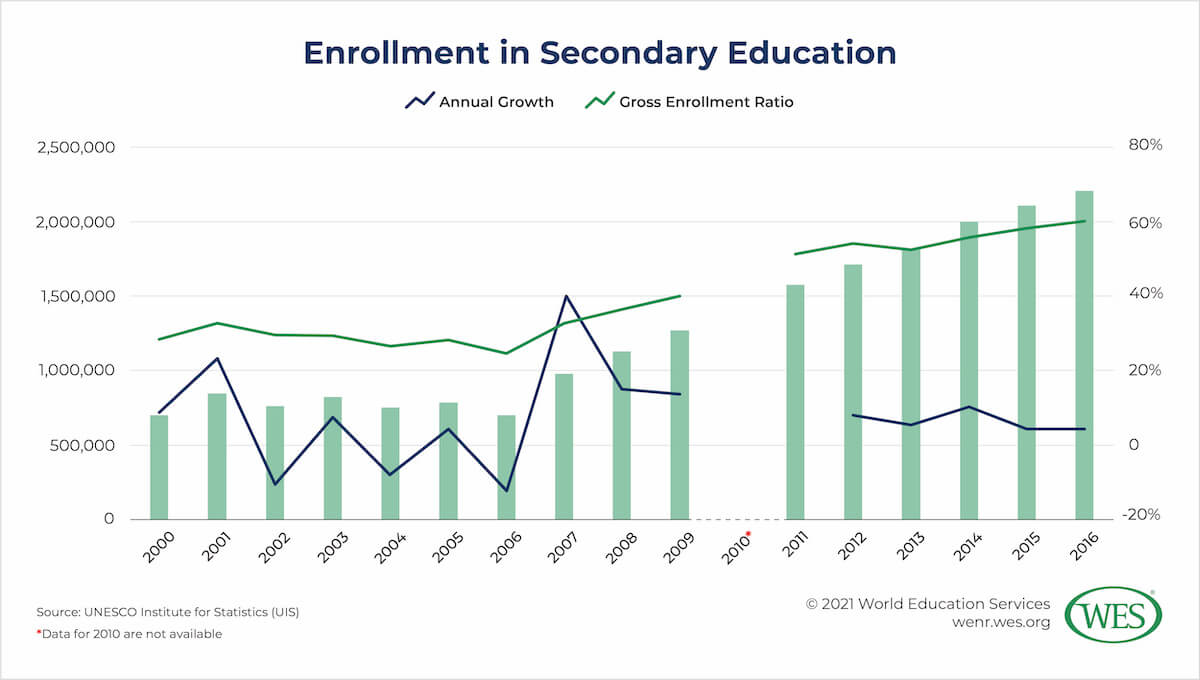

Cameroon is the second-largest source of international students from sub-Saharan Africa, according to data from the UNESCO Institution for Statistics [34] (UIS). In 2018, 26,169 Cameroonian students studied for a tertiary degree overseas, well behind Nigeria (76,338), but nearly a third more than the next closest country, Zimbabwe (19,679). Since 2000, the number of Cameroonians studying overseas has nearly doubled, driven in part by steady economic growth, rising secondary enrollment rates [35], and a ballooning youth population [36].

Less positively, that growth has also been driven by political instability, low-quality domestic higher education options, and demand for university seats [37] that is well in excess of capacity. A report [38] submitted by the government of Cameroon to the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights [39] in 2020 noted that Cameroonian universities had seats for a maximum of 295,128 students, well below the 450,000 students hoping to be admitted. Dim post-graduation employment prospects at home may also drive many to study abroad. There they would join a large contingent of Cameroon’s most qualified graduates. In a report from the mid-2000s, countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) identified 42 percent of Cameroonian immigrants [40] as “highly qualified,” a high level compared with immigrants from other countries.

For decades, these factors have been reflected in high outbound mobility ratios, which peaked in 2000 when more than one-fifth of all Cameroonian university students studied overseas. Nearly 20 years later, the outbound mobility ratio [41] remains high, standing at 7.9 percent in 2018—well above world (2.5 percent) and sub-Saharan African (4.7 percent) averages.

Top Destination Countries

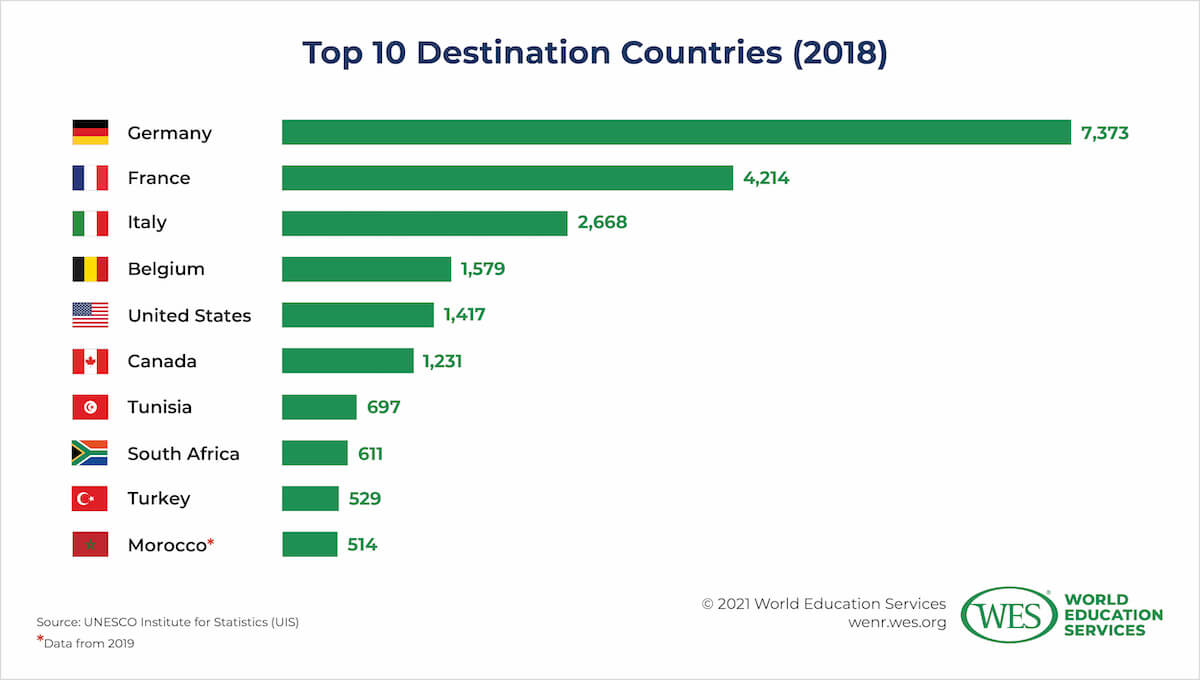

Most Cameroonian students are attracted to destinations in Europe, North America, and North Africa. Germany attracts a solid plurality of all outbound degree-seeking Cameroonians, with 7,373 studying in Germany in 2018, the 10th-largest international student population in Germany in 2019, according to data from the German Academic Exchange Service [43] (DAAD).

Generous scholarship programs [44], rosy post-graduation employment prospects [45], relatively low tuition fees, and an excellent network of universities all attract Cameroonian students to Germany. The country’s reputation as a global leader in engineering is likely a significant draw as well—more than half of all Cameroonians in Germany are enrolled in engineering programs [46]. Flexible admission requirements also ease access—Cameroonian students can enroll in German institutions on the basis of their secondary education qualification [47]. Although many university programs in Germany are taught in English [48], some familiarity with the German language may ease the transition for Cameroonian students. German is a popular language in the country’s education system, and Cameroon has the highest number of German speakers [49] of any country in Africa.

A high proportion of Cameroonian students in Germany are enrolled in bachelor’s degree programs, nearly three-quarters in 2018 [50]. Dropout rates, while high—23 percent of all Cameroonian bachelor’s students from the class of 2012/13 dropped out before graduation—are well below the average for international students in Germany—that same year, 45 percent of all international students in Germany left early.

The popularity of Francophone countries—colleges in five of the ten most popular countries teach in French—is more easily explained: More than eight in ten Cameroonians live in Francophone regions. France is a particularly popular destination for Cameroonian international students—in 2018, France hosted 4,214 Cameroonian degree-seeking students, second only to Germany. Even after Cameroon’s independence, France’s economic and cultural influence in Cameroon has remained strong. Since the 1990s, France has promoted bilateral higher education cooperation [52] through initiatives such as the Formations Ouvertes et à Distance [53], which has allowed Cameroonian students to study programs offered by French institutions without leaving the country. Broadly similar education systems also facilitate mobility from Cameroon to France.

These ties have helped France attract a body of Cameroonian students more diverse than that studying in France’s neighbor to the east. Of the 7,952 Cameroonian students reported by the Ministère de l’Enseignement supérieur, de la Recherche et de l’Innovation [54] (MESRI)2 [55] as studying in France in the 2019/20 academic year, 42 percent were enrolled in undergraduate programs, 49 percent in master’s programs, and 9 percent in doctoral programs. Of these students, 38 percent were enrolled in science programs; 20 percent in economics, management, or administration; 17 percent in literature, languages, humanities, or social sciences; 14 percent in law or political science; and 12 percent in health or medicine. The previous year, 60 percent [56] were enrolled in universities, 15 percent in business and management schools, and 12 percent in engineering schools.

Closer to home, Tunisia—where Cameroonian students frequently make up one of the largest contingents of international students—South Africa, and Morocco are popular destinations for Cameroonian students. These countries boast some of the continent’s best higher education institutions and, in the case of Tunisia and Morocco, share with a large proportion of Cameroonians a similar language, education system, and religion—nearly a quarter of Cameroon’s population is Muslim [57].

Large numbers of Cameroonian students likely head to China as well. Although official numbers are less forthcoming, media reports [58] suggest that around 3,000 Cameroonians are currently studying in China. China has made a concerted effort [59] to attract African students in recent years. Scholarships provided by the Chinese government help cover the costs of study, room and board, and even travel to and from China. Other scholarships are provided by Confucius Institutes (CIs) which promote Chinese language and culture and until recently [60] were directly funded by the Chinese government. Cameroon’s first and only full CI [61] was established in 2007 at the University of Yaoundé II. Since then, roughly 40 smaller CI teaching centers or Confucius Classrooms [62] have been established throughout the country. They currently enroll more than 10,000 Cameroonian Chinese language learners [63].

The United States and Canada

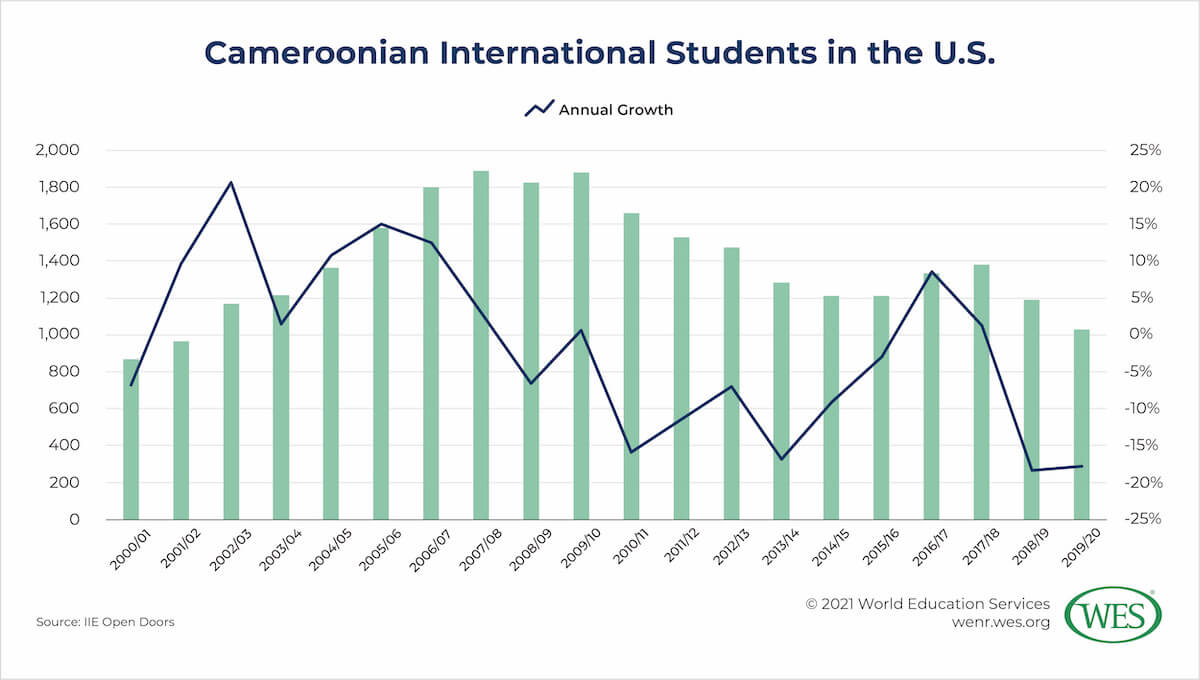

Although Cameroon is the second-largest global source of international students from sub-Saharan Africa, it is just the 10th-largest sub-Saharan African source of international students in the United States. Just 1,027 Cameroonians—or less than 5 percent of all internationally mobile Cameroonian students—studied in the U.S. in the 2019/20 academic year, according to the Institute of International Education’s (IIE’s) Open Doors report [64].

A variety of reasons may account for the low numbers, including the high tuition fees charged at many U.S. colleges and universities. EducationUSA’s 2018 Global Guide [65] noted that 42 percent of Cameroonians in the U.S. study at community colleges, a tendency at least partially explained by the relative affordability of community colleges. The guide also hints at the importance of a strong return on investment to Cameroonian students, noting that these students often pursue fields such as “business, health, and political science” that “enable them to return home and enter the private sector either by opening their own business or joining a family business.” The low English proficiency of most Cameroonians [66]—less than one-fifth of the population lives in Anglophone regions—likely dissuades many students from attending school in the U.S.

Considerations of overall cost—including tuition, travel fare, and room and board—and return on investment likely account for the high proportion of Cameroonian students enrolled in degree programs, as opposed to short-term, non-degree programs, such as intensive English—just 4 percent were enrolled in non-degree programs in the 2019/20 academic year according to IIE data [67]. As in Germany, most register in undergraduate programs (55 percent), followed by graduate programs (28 percent), and the Optional Practical Training (OPT) program (13 percent).

Following the Great Recession [69], these factors contributed to a steady decline in the number of Cameroonian students enrolled in the U.S. Since peaking at 1,891 in the 2007/08 academic year, enrollment has declined by 45 percent. The decline was reversed only briefly in 2016/17 and 2017/18, when the forced closure of schools and universities [70] in the country’s Anglophone regions briefly drove English-speaking students to the U.S. Since then, the Trump administration’s isolationist rhetoric and policies—such as the travel ban, which, although it never directly impacted Cameroon, was eventually extended to neighboring Nigeria [71]—likely dissuaded many Cameroonians from studying in the U.S.

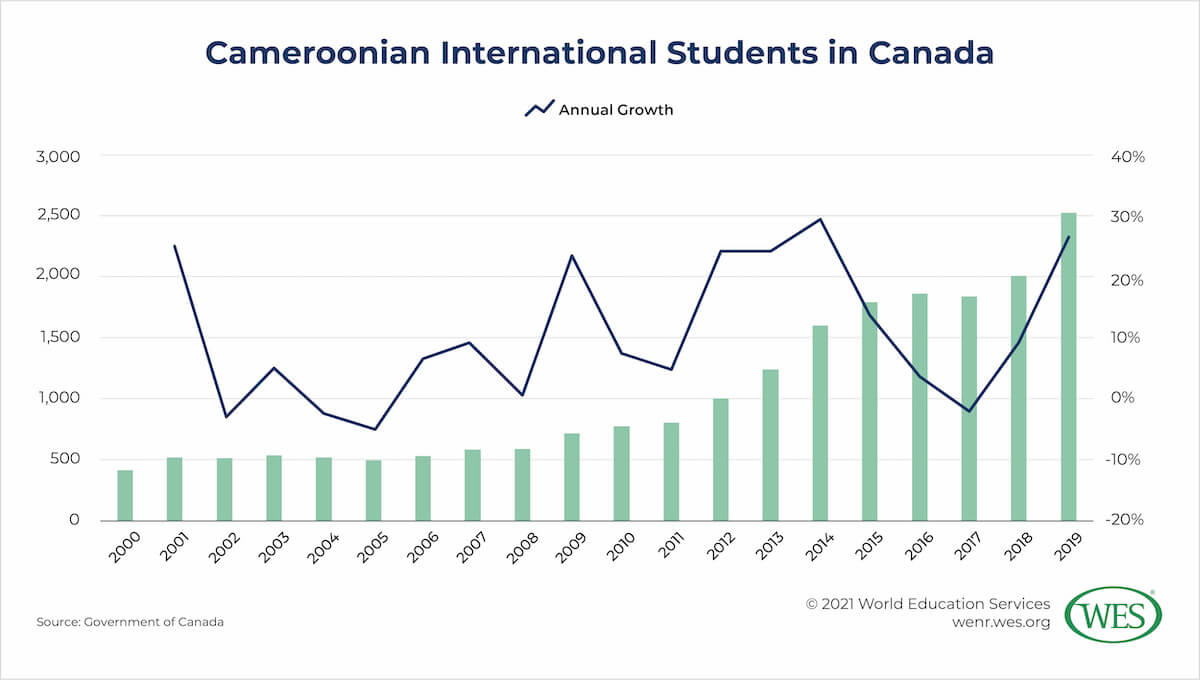

Since the start of the twenty-first century, Canada has experienced far steadier growth in Cameroonian international student enrollment than the U.S. Over the past 10 years enrollment has more than tripled, peaking at 2,525 in 2019, according to government statistics [73], well above the number hosted by the U.S., although differences in data capture methodology make direct comparison difficult. Over the past three years, the divergence has been particularly sharp—while the U.S. saw a decline of 26 percent between 2017/18 and 2019/20, Canada saw growth of 37 percent between 2017 and 2019.

Canada’s pronounced growth is likely driven in part by the government’s more welcoming attitude to international students and immigrants. Given the dearth of jobs available to graduates in Cameroon, the decision [74] of Canada’s Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship (IRCC) in late 2020 to award French-speaking Express Entry candidates additional points is likely to further draw French-speaking Cameroonians to Canada.

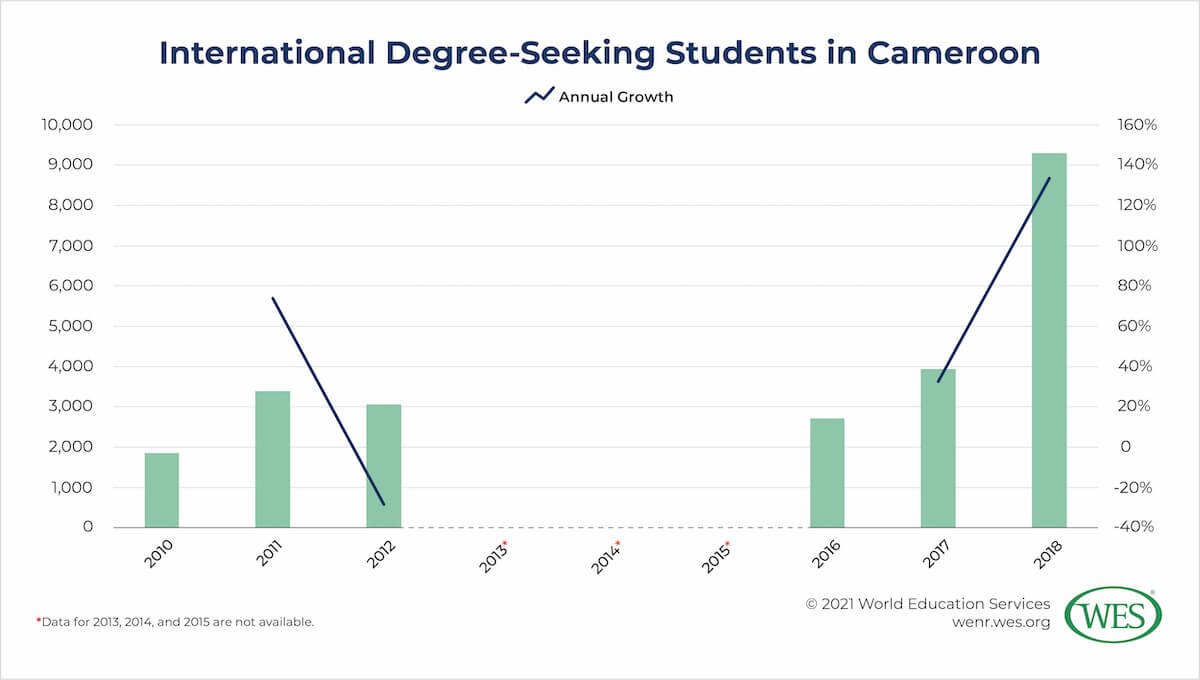

Inbound Mobility

Although a minor player compared with those of major destination countries, Cameroon’s higher education institutions still attract sizable numbers of international students, largely from neighboring countries. In 2018, Cameroon was the fifth-largest host of international students in all of Africa, according to UIS [75], and the largest in Central Africa by a wide margin, although reporting from other Central African nations is limited. Despite its faults, Cameroon’s higher education system is widely recognized as Central Africa’s strongest, and in recent years it has become a popular destination for students from other Central African nations, most notably Chad.

In 2017, Chadian students made up two-thirds of all international students in Cameroon. A sharp increase in Chadian international student enrollment likely drove the rapid growth (136 percent) in international student enrollment in Cameroon between 2017 and 2018. Although country-level data for 2018 is unfortunately incomplete, among historically significant source countries, Chad is the only country whose numbers are not reported for 2018 in the UIS database [76].

Chadian students no doubt choose Cameroon [77] over the low quality and insufficient capacity of their own country’s higher education system. Chad’s membership in the Economic and Monetary Community of Central Africa (CEMAC) also allows its students to pay the same low registration fees charged to Cameroonians at public universities, although many Chadians complain of additional unexpected education expenses and a high cost of living. The lifting of visa requirements [78] for travelers from CEMAC countries in late 2017 also eases interregional mobility.

The establishment in Cameroon of a number of important internationally and regionally sponsored “centers of excellence [80],” which act as continent-wide knowledge hubs, facilitating academic and research collaboration between institutions in different countries, also attract African students to the country. Since 2013, the Cameroon campus of the Pan African University [81] (PAU)—one of the first three PAU locations established on the continent—hosted by the University of Yaoundé II, has accepted students from across Africa to study governance and human and social sciences. That same year, Cameroon was selected to host one of the first African Centers of Excellence [82] (ACE). A World Bank initiative aimed at developing higher education institutions in Africa, the ACE initiative seeks to “improve the quality, quantity and development impact of postgraduate education in selected universities through regional specialization and collaboration.” In Cameroon it led to the establishment at the University of Yaoundé I of the African Center of Excellence in Information and Communication Technologies [83] (CETIC), which offers postgraduate degrees in information technology and telecommunications.

The Education System of Cameroon

Cameroon’s colonial past still shapes its education system to a notable degree. Prior to reunification, British and French colonial administrators imposed on the territories under their control education models similar to those used in the metropole. The two models diverged sharply, not just in qualification names and durations, but also in governance structures and oversight mechanisms. French administrators, hoping to promote the assimilation of Cameroonians into French culture [84], established a highly centralized system of education administration. British administrators, their attention focused elsewhere, took a more hands-off approach and adopted a more decentralized administrative structure. The British also tended to favor the use of local languages in schools, although the importance of English to the mandated territory’s government and economy guaranteed its spread among the general population. Administrators in French Cameroun often favored the French language in educational institutions.

In the decade following independence, the Francophone-dominated federal government established central ministries to oversee post-primary and higher education in the capital, Yaoundé, located in former French Cameroun. Administration of elementary education, however, was left to each of what were, at the time, federated states—a political arrangement that offered greater autonomy in education decisions and is often looked back on favorably by Anglophone Cameroonians today.

The country’s 1972 constitution sharply curtailed regional autonomy, transferring the power to appoint and dismiss regional and divisional officers to the president. As a result, a disproportionate percentage of French-speaking officials and government employees, some lacking even rudimentary knowledge of English, were appointed to high governmental offices and jobs, including regional education councils and public schools, in Anglophone Cameroon. Political exclusion from local education ministries was a major driver of the unrest that broke out in the country’s Anglophone regions in 2016.

Despite this centralization, two different systems still coexist today. While in theory students proving that they possess the requisite language skills can transfer from an institution in one linguistic system to an institution in the other, reality has often been different. Even today, besides languages of instruction, the education systems often differ in qualification framework and curricula, making transferring from one to the other difficult.

Despite these deep-rooted differences, harmonizing the two systems has long remained a goal of policymakers, even if success has often proved elusive. Recent measures, such as the nationwide transition to a three-cycle system of higher education in 2007, have helped align the curricula and lengths of certain stages of both education systems, although the complaints [10] expressed by Anglophone activists not too many years ago suggest that these changes have done little to alleviate inequality between the two systems.

But both the Francophone and Anglophone systems face other challenges together. Cameroon spends just 3.1 percent of its GDP [85] on education, well below averages [86] for both the world (4.5 percent) and sub-Saharan Africa (4.3 percent). Education is also not equally accessible to all Cameroonians—wide disparities in access still exist between boys and girls, rich and poor, and those in urban and rural areas. Many of these issues are especially acute at the higher education level, where access remains restricted to a privileged few.

Despite these challenges, in certain areas, the education system has made impressive progress since reunification. By the early years of the twenty-first century, Cameroon had extended elementary education to nearly every eligible child. In the decades since, the percentage of eligible youth enrolled in secondary and higher education has increased rapidly, although higher education enrollment remains low. As a result, literacy rates have risen dramatically, increasing from 41 percent in 1976 to 77 percent in 2018 for adults above the age of 15 [87], and from 69 percent to 85 percent for youth between the ages of 15 to 24 [88]. While impressive in the aggregate, country-wide numbers hide widespread regional disparities. The literacy rate for rural Cameroonians between the ages of 15 and 24 was just 48 percent [89] in 2014.

Administration of the Education System

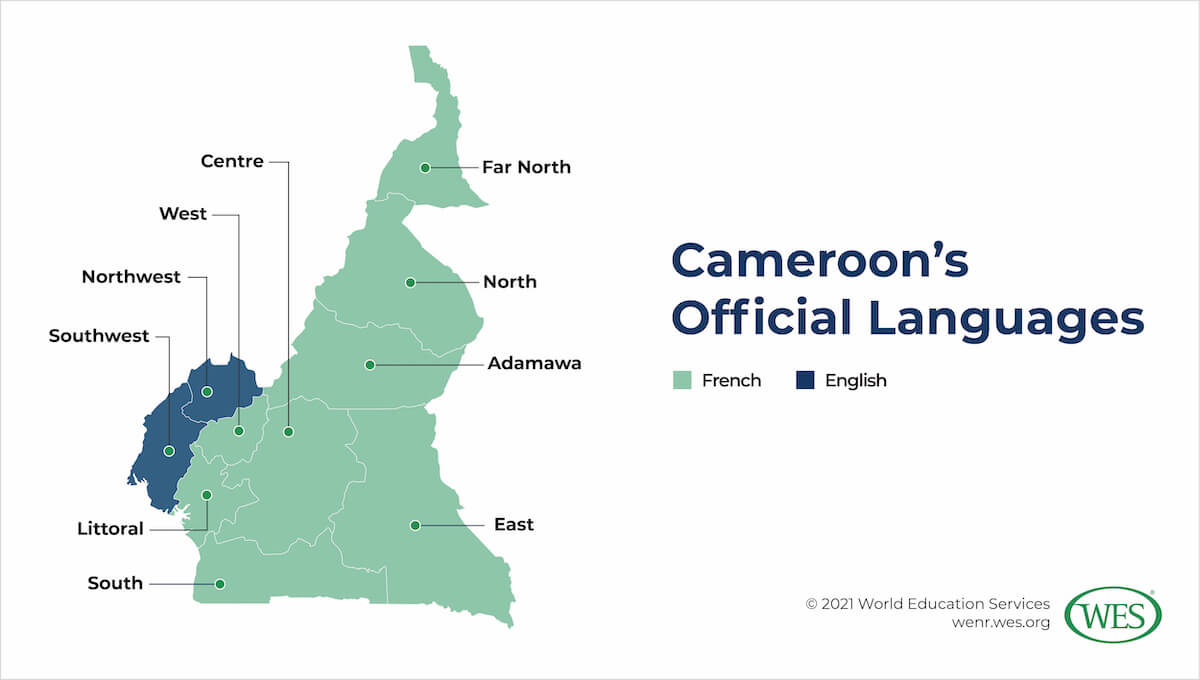

Cameroon consists of 10 regions [90] (regions), 58 divisions or departments (départements), and 360 districts (arrondissements). More than 370 local councils govern 360 municipalities and 14 cities. Two of the country’s 10 regions, the Northwest and Southwest Region, are English speaking and contain around 17 percent of the country’s population. The remaining regions are French speaking.

Although education administration in Cameroon is highly centralized, management is shared by a number of different central government ministries, a situation that significantly complicates [91] education planning and coordination at the national level. Five ministries, all located in Yaoundé, the nation’s capital, assume primary responsibility for education administration. These ministries oversee both Anglophone and Francophone educational institutions and programs, at times through specialized offices or boards that oversee aspects of just one system.

Historically, education ministers, appointed by the president, have all come from French-speaking regions. However, in 2018, in what observers have interpreted as a bid to ease tensions [92] in the country’s Anglophone regions, the president for the first time appointed a minister from an Anglophone region to head the Ministry of Secondary Education.

These ministries have been criticized for their exclusive approach to administration and policymaking—for formulating education policies and developing curricula with little input from other stakeholders—although in recent years decentralization initiatives have helped increase the representation and responsibilities of other interested parties. Decisions on how to allocate funds throughout the country are also largely determined centrally. Despite the requirement that the Ministry of Finance [93], or Ministère des Finances, base its decision on local needs as expressed by regional delegations, a 2012 World Bank report [94] found that budget decisions rarely “take into account the specific needs of the different regions and delegations.” It remains to be seen what impact if any the recent introduction of open elections for Regional Councils will have on the governance and funding of the education system.

The Ministry of Basic Education [95], or the Ministère de L’Education de Base (MINEDUB), oversees nursery and elementary education. Like the other education ministries, MINEDUB develops curricular guidelines, elaborates national education policies, and regulates the establishment and operation of public and private institutions. MINEDUB remains the most decentralized [96] of the country’s education ministries and is therefore able to respond more nimbly to unique regional challenges and opportunities than many of the other ministries.

The Ministry of Secondary Education [97], or the Ministère de l’Enseignement Secondaire (MINESEC) is responsible for lower and upper secondary education. It regulates both general academic and technical/vocational streams of secondary education, developing curricula and policies aimed at equipping students with the knowledge and skills they need to continue on to post-secondary education or to enter the job market in entry-level technical positions. MINESEC also supervises the examination bodies responsible for lower and upper secondary academic and technical exit examinations: the Office du Baccalauréat du Cameroun [98] and the Cameroon General Certificate of Education (GCE) Board [99]. MINESEC also oversees the education and training of nursery and elementary school teachers.

The Ministry of Technical and Vocational Education [100], or Ministère de l’Emploi et de la Formation Professionnelle (MINEFOP), is responsible for other vocational training programs [101] throughout the country which are conducted at smaller public and private training centers. Besides a central administrative office, MINEFOP also consists of an inspection department and regional and departmental delegations, which coordinate and oversee the local implementation of regulations and initiatives. The ministry also supervises [102] a number of public vocational training centers, such as Vocational Training Centers of Excellence, or Centres de Formation Professionnelle d’Excellence, and Sector Vocational Training Centers, Centres Sectoriels de Formation Professionnelle, among others.

Responsibility for higher education, at both public and private institutions, rests with the Ministry of Higher Education [103], or Ministère de l’Enseignement Supérieur (MINESUP). It is responsible for the elaboration and implementation of a higher education policy aligned with the needs of the nation’s government and economy. For public universities, MINESUP administers Competitive Entrance Examinations and appoints their vice-chancellors, although more independent university governing councils are often responsible for staffing decisions. MINESUP is also ultimately responsible for accrediting private institutions, although it typically acts on the advice of the National Commission for Private Higher Education (NCPHE), a nominally independent quality assurance body. MINESUP also oversees the education and training of secondary teachers and teacher trainers. This training is offered at university colleges.

Unlike the other education ministries, the fifth ministry, the Ministry of Youth and Sports [104], or Ministère de la Jeunesse et de l’Education Civique (MINEJEC), does not oversee a specific stage of education. Instead, it coordinates general youth affairs and policies, many of which impact educational outcomes and initiatives.

Cameroon Vision 2035

In 2009, the government adopted Cameroon Vision 2035 [105], a development framework which aims to make Cameroon “an emerging, democratic, and united country in diversity” by 2035. The Vision identifies a number of important goals, such as alleviating poverty, joining the ranks of middle-income and newly industrialized countries, strengthening democratic institutions, and promoting national unity, while respecting the country’s diverse ethnicities and linguistic communities.

More definite goals and indicators for the first phase of the Vision, which were to last from 2010 to 2020, were identified in the Growth and Employment Strategy Paper [106] (GESP). Among the key goals laid out in the GESP are an average GDP growth rate of 5.5 percent per year, a reduction of the income poverty rate from 40 to 29 percent, and the reduction of underemployment from 76 percent to 50 percent. The latter would be achieved through the creation of 100,000 formal jobs [107]—as of May 2011, 90 percent of employment in Cameroon was informal [108], an arrangement with notoriously precarious work conditions and periods of unemployment.

The GESP also called [109] for the implementation of 18 development programs to improve all levels of the country’s education system and aim at developing the country’s human capital to a level “capable of sustaining economic growth.” Among the changes called for are curricular reforms aimed at aligning education with the country’s social and economic development needs. In response, curricula has been developed at the higher education level to provide graduates with the skills demanded by employers [110]; at the secondary level, competency-based curricula [111] has been introduced.

Data [112] released in 2019 suggest that while there have been improvements, many of the central goals of the GESP 2010-2020 have not yet been met. The average annual growth rate stood at 4.5 percent, instead of the 5.5 percent hoped for, while poverty rates had declined by only 3 percent, well below the intended 10 percent.

Education also plays an important role in the second phase of the Vision, outlined in the National Development Strategy 2020-2030 [113] (NDS30). THE NDS30 lays out a vision of an education system able to give every graduate English and French fluency and prepare them for work in fields important to the country’s social and economic development. It also seeks to ensure that all children graduate from elementary education and that regional disparities in school infrastructure and staffing are reduced.

In addition, the NDS30 puts forward ambitious plans to boost technical and vocational training, including the “Train My Generation” program, a “certified mass training and capacity-building programme for workers in the informal sector.” It also seeks to increase enrollment in vocational and technical training from 10 percent to 25 percent of all secondary students, and from 18 percent to 35 percent of all higher education students. Given the prevalence of informal employment in rural areas, these programs could have a powerful impact on the country’s impoverished rural population.

Academic Calendar and Language of Instruction

In Cameroon, the academic year begins in September and ends in June. At higher education institutions, the year is typically divided into two semesters, each lasting between 14 and 16 weeks and containing from 45 to 60 lesson hours.

Although Cameroon’s constitution established both French and English as official languages, French is used far more frequently in government, business, and everyday life. While more recent data are unavailable, in 2005 [114], 57 percent of the population ages 15 and above spoke French while just 25 percent spoke English.

Cameroon’s 1996 constitution [115] also requires the state to “guarantee the promotion of bilingualism throughout the country.” Government efforts to encourage bilingualism have since leaned heavily on the education system. The loi n° 98/004 du 14 avril 1998 d’orientation de l’éducation au Cameroun [116], passed in 1998 and still the country’s guiding legal framework for education, enshrined “bilingualism at all levels of education as a factor of national unity and integration.”

Educational approaches to the encouragement of bilingualism have evolved over time. An earlier approach [117], termed opération bilinguisme, fully immersed young Cameroonians in both languages, requiring that the last three years of elementary education be taught in the language other than that used in the first three. Although ambitious, the program was abandoned in the late 1990s, undermined by insufficient planning, oversight, and funding.

Today, most schools offer instruction exclusively in one language, although at most levels students are required to take courses in the other official language. In the schools following the Francophone system, English is a compulsory subject in all stages, from preschool to the end of upper secondary. In the Anglophone system, students are only required to take a French language course at the end of lower secondary education. In end-of-cycle examinations, students are usually required to sit for mandatory tests in the language other than that used at their school, although following upper secondary in the Anglophone system, only students who choose an arts stream [118] are required to sit for a French language test.

Bilingual schools [119] are also expanding across the country. However, despite what their name suggests, these schools are in fact two separate institutions [120], teaching two separate curricula, one in French to students enrolled in the Francophone section, the other in English to students in the Anglophone section. Although true, dual-medium schools that teach all subjects in both French and English do exist, they enroll a very limited number of Cameroonians [120].

Cameroon’s dual-medium education system raises unique challenges—qualified second language teachers are often difficult to find, especially in remote areas of the country. The system also contributes to teaching and learning disparities. In Anglophone schools, the ministry often assigns native speakers of French, some of whom lack basic English competency, to teach English-medium classes. In the run-up to the 2016 protests, Anglophone students and teachers expressed frustration with the latter issue, alleging that it causes Anglophone students to underperform on final examinations [121].

Francophone schools may also better prepare students for certain university programs. Even at the country’s two Anglophone universities, Bamenda and Buea, Francophone students outnumber Anglophone students in professional departments by a ratio of nine to one [121]. Some university entrance examinations have even been offered exclusively in French [122] or in poorly translated English, putting Anglophone applicants at a severe disadvantage.

Despite these disparities, in recent years there has been an uptick [118] in the number of French-speaking families enrolling their children in the Anglophone system. A key reason for this increase, besides the growing importance of English throughout the world, is the rising completion rates of students enrolled in Anglophone elementary schools. In the mid-2000s, 80 percent of students completed elementary school in the Anglophone system, compared with 59 percent in the Francophone system.

Despite long-standing efforts to promote bilingualism, few Cameroonians speak both languages. A popular phrase goes “C’est le Cameroun [123] qui est bilingue, pas les Camerounais.” “It is Cameroon that is bilingual, not Cameroonians.” In 2005, just 12 percent [124] of all adults spoke both languages. More than a quarter [114] (29 percent) spoke neither.

Instead, the most widely spoken and understood languages [125] are likely Cameroonian Pidgin English or Camfranglais, a mixture of French, English, and local languages. Beside these, Cameroonians speak a multitude of local languages. According to the latest edition of Ethnologue [126], a compendium of the world’s living languages, Cameroon is the ninth most linguistically diverse country [127] in the world, with 275 languages spoken in the country.

Although decades of official neglect have endangered many of these languages, in recent years the government has moved to preserve the country’s linguistic heritage. One initiative, spearheaded by MINEDUB, introduces the teaching of five national languages [128]—Ewondo, Douala, Bassa, Womala, and Fufulde—in 43 schools throughout the country. The ministry has also instructed and trained elementary teachers to teach the languages spoken locally.

Early Childhood Education

Early childhood education (ECE), known in Cameroon as nursery school or l’enseignement maternel [129], is non-compulsory and lasts for two years, from age four to six. Its main goal is to prepare students to enter elementary school, and it is administered by the Ministry of Basic Education (MINEDUB).

MINEDUB also develops curricular guidelines that nursery schools throughout the country are required to follow. Both the English [130] and French [131] curricula, updated in 2018 for the first time since 1987, emphasize science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) subjects, and are designed to lay the “foundation for sustainable learning.” Students are not awarded [132] a diploma upon completion, although performance in nursery school is sometimes used to determine placement in advanced elementary school courses.

Cameroon’s formal ECE system is still young. It was given its first major push in 1998, with the passing of the national education law, the loi n° 98/004 du 14 avril 1998 d’orientation de l’éducation au Cameroun [116], which remains the guiding legal framework for education in Cameroon. The law enshrines education as a basic human right, guaranteeing all Cameroonian children equal access to education regardless of sex, language, or geographic origin. In the years since its passage, the government, with the help of international non-governmental organizations (NGOs), has initiated a number of projects aimed at boosting preschool enrollment, including the establishment of community preschool centers [133] in rural regions.

Nevertheless, as of 2019, only 36 percent [134] of children attended ECE programs, falling short of the 50 percent goal set for 2020 in the GESP. This is largely due to a lack of facilities in rural areas [135], where only 32 percent of eligible children are enrolled in nursery schools. In the North and Far North, enrollment is less than 10 percent. While gender disparities in preschool enrollments throughout the country are minimal [136], socioeconomic differences greatly affect access, with many wealthier families choosing to send their children to private preschools. Reflecting both a lack of public ECE facilities and the importance of private funds in ECE accessibility, more than half [136] (55 percent) of children attending preschool were enrolled in private preschools as of 2017, while 42 percent were enrolled in public preschools, and just 2 percent in community preschool centers.

Elementary Education (l’Enseignement Primaire)

Elementary education, known as l’enseignement primaire [129] in the Francophone system and primary education in the Anglophone system, is the only compulsory stage of education in Cameroon. Elementary education in both systems lasts for six years, from age 6 to 11. Elementary schools typically follow the linguistic system that corresponds to the predominant language of the region in which they are located, although this is not always the case. A small percentage of schools, typically located in urban areas, in English-speaking regions follow the Francophone system, and vice versa. These schools often educate [137] the children of migrants from other regions of Cameroon.

A presidential decree [138] issued in 2001 made attendance at public elementary schools, known as écoles primaires or government primary schools (GPS), free of charge, although logistical challenges have often forced parents to pay out of pocket. The government currently provides a financial aid package [139] to families with children, intended to cover tuition and additional educational expenses, such as fees for textbooks, examinations, and salaries for non-contract teachers, known as Parent-Teacher Association (PTA) teachers. However, the aid often arrives late, prompting many parents to forgo purchasing school supplies or contributing to PTA teacher salaries, resulting in low textbook-to-student ratios and low pay for temporary teachers. Although the government had planned to transition all PTA teachers to contract work by 2016/17, that implementation status is unclear.

Despite these challenges, the decree had a momentous impact on the country’s education system, driving the gross enrollment ratio [140] (GER) up from 85 percent in 2000 to 101 percent in 2001. It also sparked the beginning of a period of vigorous elementary enrollment [35] growth, with the number of students enrolled in elementary schools doubling from 2.2 million in 2000 to 4.4 million in 2019.

But the speed with which enrollment expanded has also strained the country’s public education infrastructure, resulting in today’s overcrowded and understaffed schools. In 2018, there were around 45 students per teacher [141] at the elementary level. Poor conditions at public schools have driven many parents—or at least those able to afford it—to enroll their children in private schools. Today, about 25 percent of elementary students [142] attend a private school.

Although today, elementary education in both systems lasts for six years, prior to the 2006/07 school year, the length of elementary education differed, lasting six years in the Francophone system, and seven years in the Anglophone system. The extended struggle to harmonize the two systems exemplifies the long-standing reluctance [143] of Cameroonian policymakers to adopt and implement a unified model. Attempts [84] to harmonize the two systems began shortly after political unification, with both English- and French-speaking regions agreeing to make concessions to bring the structure, if not yet the curriculum, of their education systems into alignment by 1965. Under the agreement, Anglophone regions would reduce their elementary cycle from eight to six years, and Francophone regions would abandon their four-year lower secondary, three-year upper secondary (4+3) system, adopting the 5+2 structure prevalent in Anglophone regions. But only limited progress was ever made—in 1963, Anglophone regions reduced the length of their elementary education cycle from eight to seven years, with plans to reduce it to six the following year. After the Francophone side missed a planned deadline to adjust its secondary cycle, recriminations and disagreements stalled further reforms, leaving elementary education one year longer in the Anglophone regions for 43 years.

Attempts to harmonize the two systems have not been limited to the length of education cycles—curricular standardization has also long been a goal of Cameroonian policymakers, although success was achieved only recently. In the 2018/19 school year, for the first time in the country’s history, all Cameroonian children, whether they attended Francophone or Anglophone schools, were taught the same elementary school curriculum [144].

Elementary education is divided into three levels, each of which lasts for two years. In the Anglophone system, each year is referred to as a class, from the first year, class one, to the final year, class 6 [145]. The terminology is more complicated in the Francophone system. The first level, cycle des initiations [146], comprises the section d’initiation au langage (SIL) and the cours préparatoire (CP) ; the second level, the cycle des apprentissages fondamentaux [147], comprises the Cours Elémentaire Première Année (CE1) and Cours Elémentaire Deuxième Année (CE2) ; and the third level, the cycle des approfondissements [148], comprises the Cours Moyen Première Année (CM1) and Cours Moyen Deuxième Année (CM2). At the end of the third, and final, level [145] in both systems, students are expected to have acquired seven core skills [149], including the ability to communicate [150] in both English, French, and, introduced for the first time in the 2018/19 curricula, one local language. Other core skills [151] include the ability to use the basic concepts and tools of mathematics, science, technology, and information and communication technology (ICT).

At the end of the sixth year, students sit for the Certificat d’Études Primaires [152] (CEP) or the First Leaving School Certificate [153] (FLSC), examinations developed and administered by the Direction des Examens, des Concours et de la Certification [154], a department of MINEDUB. Examinations are held [155] in May and June each year and consist of 12 mandatory subjects. Students must achieve a minimum total score, which is based on their weighted score in each subject, of 10 out of 20, or 50 percent, to graduate. Results are announced over the radio and in local media. Students hoping to proceed to either secondary general education or vocational education must sit for and pass a separate entrance examination [121].

Secondary Education (l’Enseignement Secondaire)

Students completing elementary education can enroll in one of two secondary education streams: secondary general education or vocational and technical education. Secondary general education is an academic stream designed to prepare students for higher education. Unlike elementary education, secondary general education, or l’enseignement secondaire général, is neither compulsory nor free. Tuition, examination fees, and the cost of textbooks and uniforms prevent [156] many young Cameroonians from less well-off families from pursuing secondary education. A full secondary education is out of reach for other groups as well—secondary completion rates of female students [157] and students from rural communities are far lower than those of male and urban students, respectively.

Notwithstanding these challenges, secondary enrollment has grown rapidly in recent decades. Driven by the country’s growing economy and the introduction of free, universal elementary education, secondary enrollment reached 2.2 million [35] in 2016, the last year for which data are available, more than double the number enrolled 10 years earlier. That rapid increase in enrollment extended access to secondary education to far more eligible Cameroonians. Cameroon’s secondary gross enrollment ratio (GER) grew from 32 percent [140] in 2007 to 60 percent in 2016, the highest in Central Africa.

But rapid enrollment growth also exacerbated a long-standing problem in Cameroonian secondary schools: overcrowding. Recent events, such as the Anglophone Crisis and attacks by Boko Haram, have further contributed to the problem, as schools not directly impacted by the unrest have scrambled to accommodate rapidly growing numbers of internally displaced students.

Anecdotal events illustrate the scope of the issue. Following the Anglophone Crisis in 2016, Anglophone enrollments at the Government Bilingual High School in Dschang, located in Cameroon’s French-speaking West Region, grew by two-thirds, or 800 students, between the 2015/16 and 2018/19 school years alone, according to a recent study [159]. The unrest also affected Francophone students at the school. The student population in the school’s Francophone section shrank by nearly 9 percent over the same period—a result, the authors suggest, of ministerial instructions to the school principal to prioritize displaced students. Reports from other regions of the country suggest that the relocation of Anglophone students to Francophone regions has even prompted some previously Francophone-only schools to introduce Anglophone sections [159], a linguistic accommodation not always coincident with necessary infrastructural improvements.

Cameroon’s secondary education system faces other challenges. Schools are not only frequently overcrowded, they are also often poorly maintained or closed entirely. Some, especially rural schools, lack electricity and proper sanitation. Weak teacher supervision and support often leaves secondary school teachers underprepared, especially in remote areas of the country. But even those teachers who are adequately prepared must use a curriculum that a 2019 World Bank report [101] criticized as “highly theoretical” and lacking an emphasis on “critical thinking, problem solving and socio-emotional skills.”

Lower Secondary

Secondary education in both the Anglophone and Francophone systems is divided into lower and upper levels. While the secondary education cycle in both systems lasts seven years, the duration of lower and upper secondary levels differs between the two systems.

In the Anglophone system, lower secondary education, known as the first cycle in Cameroon, lasts five years, from the first form to the fifth form (corresponding to grades seven to 11). Most Anglophone students attend public institutions, known as government secondary schools, that teach only the English curriculum, although there are small but growing numbers of public and private bilingual secondary schools.

Since the 2012/13 academic year, the first cycle curriculum [160] has been divided into five “Areas of Learning”: languages and literature, science and technology, social sciences (or the humanities), personal development, and arts and national cultures. Students take courses from each learning area, including both English and French, mathematics, physics, computer science, history, citizenship education, sports and physical education, national languages and culture, and art, among others. At the end of the fifth form, students at both public and private schools sit for either the General Certificate of Education, Ordinary Level [161] (GCE OL) or the Bilingual GCE OL [162], which includes a more advanced French language component. Students can sit for up to 11 subjects [161], including three mandatory examinations in English, French, and mathematics. Examinations are administered by the GCE Board.

In the Francophone system, lower secondary education, known as the premier cycle, lasts four years, from sixième to troisième (or grades seven to ten). Public schools catering exclusively to Francophone students are known as lycées. At the end of four years, students sit for the Brevet d’Études du Premier Cycle [163] (BEPC), a lower secondary exit examination developed and administered by MINESEC.

Regarded as equivalent within Cameroon, the GCE OL and the BEPC grant earners admission into upper secondary education in their respective systems. Both examinations are typically administered in late May; however, because of the pandemic, both sittings and the issuance of results were delayed in 2020.

Upper Secondary

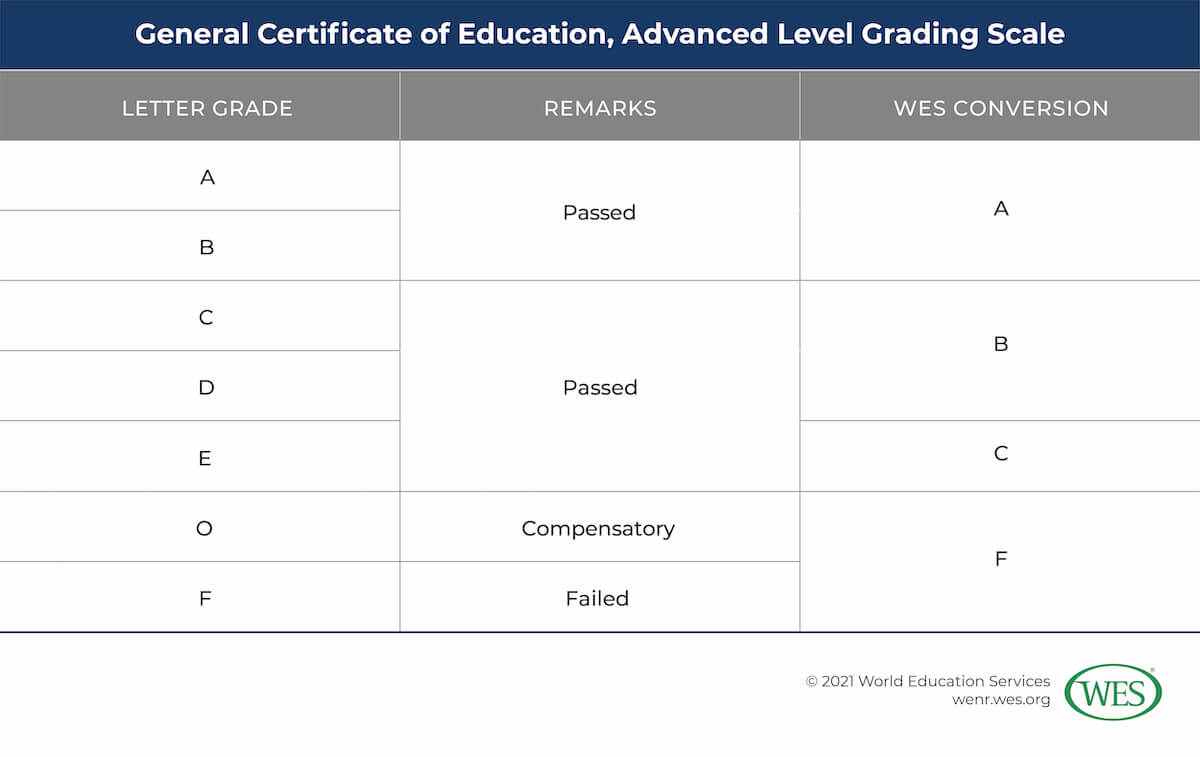

The length of study at the upper secondary level, known in Cameroon as second cycle or deuxième cycle, also varies between the two systems. Students enrolled in the Anglophone model study for two years, lower and upper sixth form (grades 12 and 13), before taking the General Certificate of Education, Advanced Level [164] (GCE AL).

Students sit for a maximum of five subject examinations. Grades between A and E are considered passing. While an O grade is not considered a pass at the Advanced Level, it is judged equivalent to a C grade at the Ordinary Level and is reflected on the student’s updated GCE OL certificate.

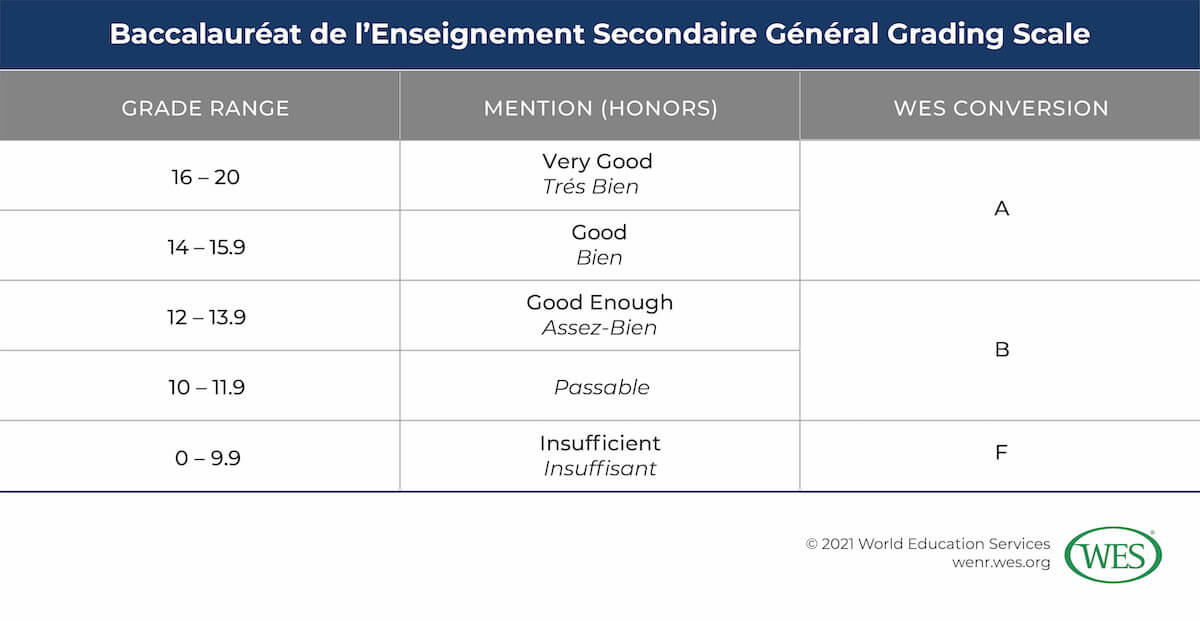

After three years, comprising seconde and première, secondary students enrolled in the Francophone system sit for the Baccalauréat de l’Enseignement Secondaire Général [166], known informally as the Baccalauréat or Bac. After the first two years of upper secondary education, students that do not intend to pursue tertiary education can take the Probatoire de l’Enseignement Secondaire Général.

From the start of the 2018/19 school year, according to the ministerial order N° 227/18/MINESEC/IGE [167] of August 23, 2018, students enrolled in the Francophone sections were able to choose from four streams, known as séries, as opposed to the two previously offered. The streams now include literary studies, scientific and technological studies, the humanities, and arts and cinematography.

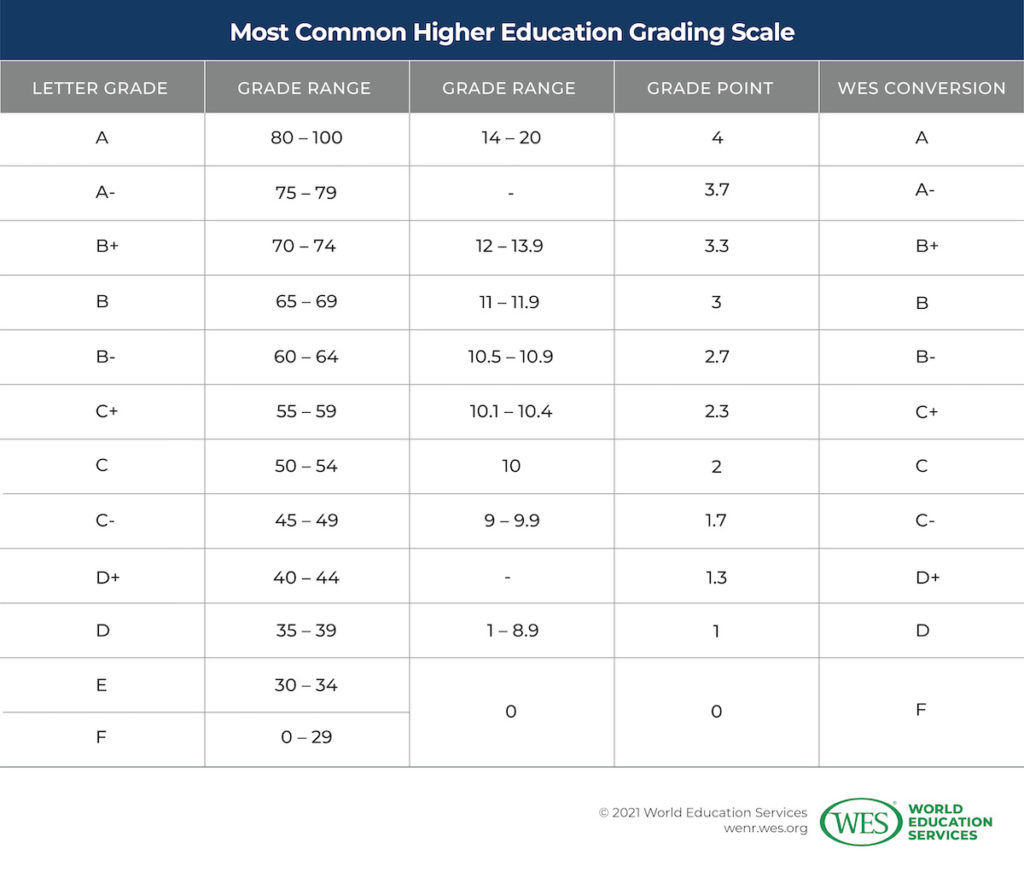

Baccalauréat’s are graded on the 20-point grading scale prevalent in France, with a 10 considered the minimum passing grade. Honors, or mentions, are conferred on students achieving certain scores.

While secondary curricula in both systems should provide equal preparation for post-secondary studies, a general perception within the country holds that pedagogical differences between the two systems [169] often better prepare Francophone students for success in higher education and the work force. In particular, the teaching methods and curriculum used for mathematics in the Francophone system are generally viewed as more closely aligned with the methods used at the university level. As a result, the Francophone system is believed to better prepare students for admission to and success in university level engineering and mathematics programs, which are among the most sought-after in the country. Data seem to support these impressions. For example, of 300 students enrolled in the mathematics department at the Anglophone University of Buea in 2009, only 13 graduated on time, nine of whom had studied in the Francophone system at the secondary level. While the Anglophone system is typically believed to better prepare students in the arts and humanities, students strong in mathematics are more likely to proceed to advanced study or to employment in higher-paid professions.

Secondary Examinations: Complications, Controversy, and COVID-19

Scores in lower and upper secondary exit examinations are of vital importance to a student’s educational future. In a country where crucial educational data are often uncollected or inaccessible, these widely published statistics are also key indicators of the challenges confronting Cameroon’s education system.

In general, success rates in lower and upper secondary exit examinations in both the Francophone and Anglophone systems are low. For example, the BEPC’s all-time high success rate is just 73 percent, achieved in 2019. The educational disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, which appeared in Cameroon in March 2020 [170], dramatically worsened the situation, causing examination scores to plummet across the board. In 2020, just 60 percent of students passed the BEPC, while baccalauréat scores fell from 61 percent in 2019 to 47 percent the following year. Similarly, the success rate [171] in the GCE AL declined from 78 percent in 2019 to 70 percent in 2020.

The reason for the decline is obvious. The health crisis severely disrupted education in Cameroon. In March 2020, students around the country were sent home to prevent the spread of infection. Shortly thereafter, the various ministries of education decided to introduce remote teaching [172], encouraging schools to provide daily instruction through a variety of platforms, such as videoconferencing, simple voice calls, and even text messaging, using messaging services such as WhatsApp. Education ministries also partnered with the government-owned television provider Cameroon Radio Television [173] (CRTV) to broadcast “School on TV,” a televised education program aimed at preparing students for upcoming national examinations.

But distance education technologies are not equally accessible to all Cameroonians. With more than three-quarters of rural Cameroonians lacking access to electricity [33] and nearly a quarter [174] of rural residents living in areas lacking a mobile phone network, many of the country’s least advantaged students were likely completely cut off from schooling. These disparities in access to distance learning technologies helped drive massive regional differences in examination scores. In 2020, in Cameroon’s well-connected and developed Littoral and Central regions, BEPC pass rates averaged 73 percent [175]. In two of its most remote regions, the North and Far North, BEPC pass rates [175] were under 42 percent.

Exit examination scores also often reflect the country’s political landscape. Just one year before the outbreak, improving success rates actually sparked political controversy, following a dramatic uptick, of nearly 31 percent, in passing rates for both the GCE OLs and ALs between 2018 and 2019. The rapid improvement alarmed many observers and stirred up accusations that the government had inflated grades to support a narrative that conditions in Anglophone Cameroon had normalized. Others attributed the improvement to the successful relocation of displaced Anglophone students to schools in safer regions. Either way, the Minister of Secondary Education, appointed in 2018 as the first Anglophone minister to hold the position, thanked all stakeholders for a “hitch-free [176]” examination cycle.

Technical and Vocational Education (l’Enseignement et la Formation Techniques et Professionnels)

Besides secondary general education, students completing elementary education can also opt to enter the technical and vocational education (TVE) secondary track, known in French as l’enseignement et la formation techniques et professionnels (EFTP). The government has made expanding TVE training a priority—as mentioned above, the National Development Strategy 2020-2030 [113] (NDS30) includes ambitious goals and projects aimed at improving TVE training and outcomes. The government also currently runs a number of programs [102] aimed at improving technical teacher training and developing the country’s network of training centers.

TVE secondary programs are offered in a variety of specialties, categorized as either industrial, techniques industrielles [177] (TI), or commercial, sciences et technologies du tertaire (STT). These programs aim at preparing students with the basic industry-relevant skills [101] that the country’s employers demand. Training is typically conducted at specialized TVE secondary schools. In 2018, around 19 percent of all secondary students were enrolled in the TVE secondary stream.

Like secondary general education, TVE secondary education is divided into two cycles. In the Anglophone system, the first cycle lasts for five years, at the end of which students sit for the General Certificate of Education, Ordinary Level Technical [178] (GCE OL Technical), also known as the Technical and Vocational Education Examinations, Intermediate Level [179] (TVE IL). Students registering for the GCE OL Technical examinations sit for a minimum of 9 and maximum of 11 subject examinations. Compulsory subjects include English, French, mathematics, and six subjects related to their specialty. Students must pass at least five subjects, including two professional subjects and one related professional subject.

The second cycle lasts two years, after which students sit for the General Certificate of Education, Advanced Level Technical (GCE AL Technical), or Technical and Vocational Examinations, Advanced Level [180] (TVE AL). Students registering for the GCE AL Technical examination select a minimum of six and a maximum of eight subjects in or related to their profession. Candidates must pass at least two professional subjects, and two related professional subjects. Both the GCE OL and AL Technical examinations are administered by the GCE Board.

In the Francophone system, the first cycle of TVE education lasts for four years, after which students sit for the Certificat d’Aptitude Professionelle [181] (CAP) administered by MINESEC. The CAP examination includes both written and practical components.

The second TVE cycle lasts for three years. Depending on the specialty, those passing the final written and practical examinations are awarded either the Brevet de Technicien [177] or the Baccalauréat de Technicien. Students can also sit for a Probatoire examination a year early.

Besides secondary schools, vocational education is also provided through a small network of training centers that offer two-year vocational training programs to adults who did not attend secondary school. These training centers include rural craft and domestic science schools [182] which offer programs in agriculture, carpentry, family and consumer sciences, masonry, and pottery. However, training centers currently play a small role in Cameroon’s TVE sector. In 2014, just 37,000 students [101] were enrolled in these centers, compared with 460,000 students in TVE secondary schools. That same year, there were around 850 training centers, more than three-quarters (76 percent) of which were private, enrolling around two-thirds (63 percent) of all students.

Students with a Baccalauréat, GCE AL, or TVE equivalents hoping for more advanced technical study can enroll in higher professional education courses, which include the Brevet de Technicien Supérieur [183] (BTS) and Higher National Diploma [184] (HND) programs. These courses of study are typically two years in length, although some specialties require three years and blend academic and technical training to prepare students for skilled professions. Two-year programs consist of 120 credits (1,800 lecture hours) and include a practical internship conducted at a company related to the student’s specialty. In line with Cameroon’s bilingual goals, students in all specialties are required to take both French and English language courses. HND and BTS programs are typically taught at specialized institutions, both autonomous private institutions and institutions affiliated with public or private universities.

Specialties, competency goals, and syllabi are determined and developed by MINESUP, which in 2015, in partnership with the business community and representatives of the nation’s higher education institutions, undertook a major review [185] of all BTS and HND programs. The review established more than 100 specialties, organized into fields of study in four sectors of the economy. These include:

- The primary sector [185]: agricultural and environmental sciences

- The secondary [186] sector [187]: engineering and technology

- The tertiary [188] sector [189]: management, business, and legal careers, and home economics, tourism and hotel management

- The quaternary sector [190]: information and communication technology

After two years of study, students sit for national examinations administered by MINESUP: the examen national du Brevet de Technicien Supérieur [191] and the HND national examination [192]. The tests are held once a year in major cities throughout the country and consist of two parts: practical examinations, typically held in April, and written examinations, usually held in June. Students who successfully pass the tests are awarded diplomas by MINESUP. While students completing BTS and HND programs are eligible for lateral admission to undergraduate programs, Cameroon’s overcrowded higher education system often precludes this route. Only a small percentage of all post-secondary students enroll in technical fields—just 6 percent [101] in 2017.

Although HND and BTS are the most common post-secondary TVE programs, others exist as well, including the Higher Professional Diploma [193] (HPD). Others, such as higher professional engineering and medical programs, are discussed below.

Higher Education (l’Enseignement Supérieur)

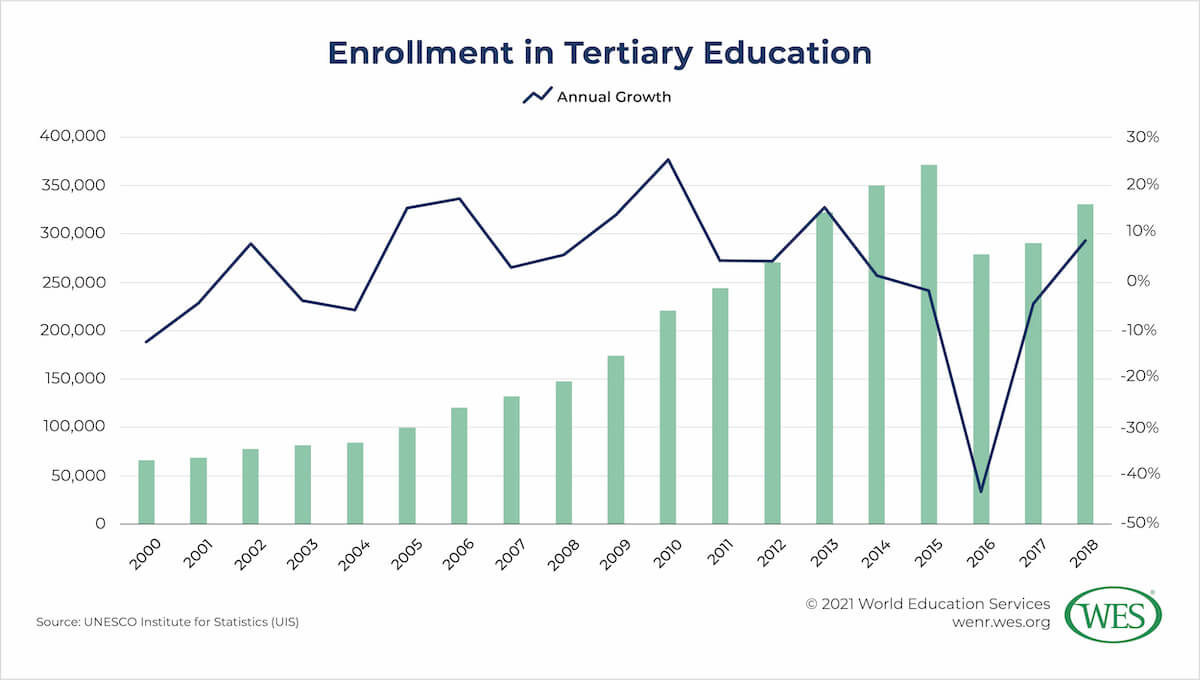

Higher education in Cameroon has expanded rapidly since the start of the twenty-first century, drawing in an ever-wider range of students, domestically and from neighboring countries. That growth has been encouragingly gender inclusive, with nearly equal proportions [194] of college-age men and women enrolled at the tertiary level.

Given the importance of higher education in economic and social development, the government has made establishing a strong, economically relevant higher education system a priority. Still, challenges persist. Despite rapid enrollment growth, access remains restricted to a privileged few. The system is also plagued by insufficient government funding, low-quality institutions, and corruption. Political and social unrest also threaten the smooth functioning of the system, while a weak labor market means that the return on investment may be less than students would have hoped.

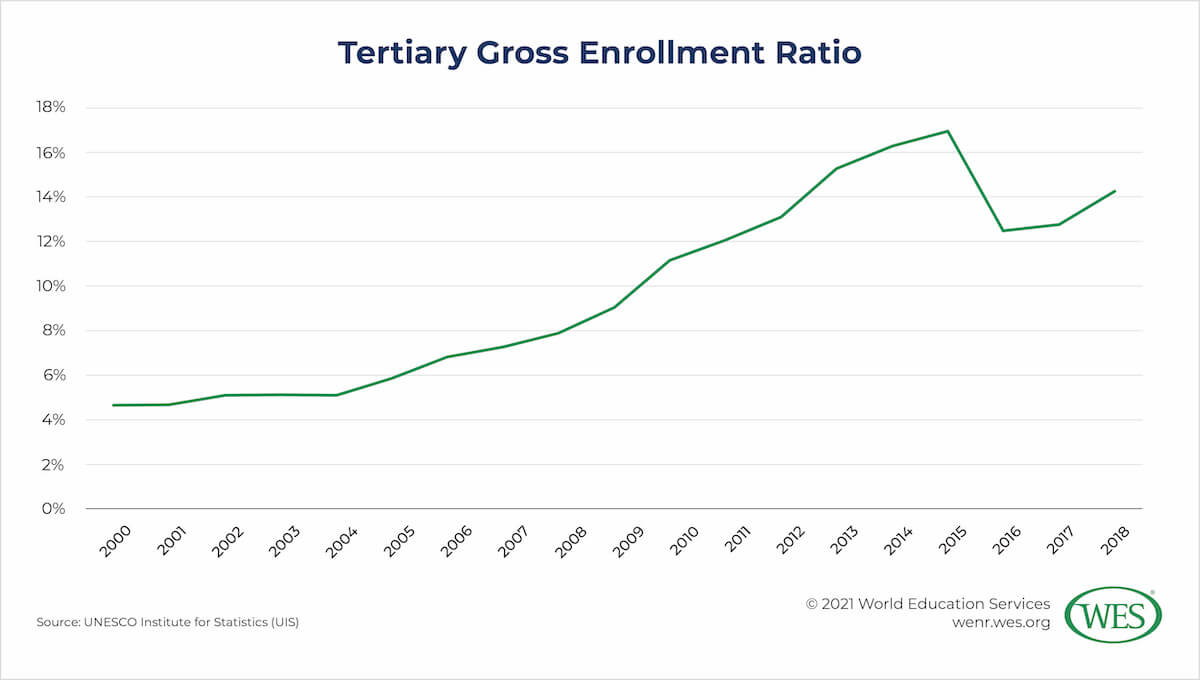

Still, steady economic growth, an expanding youth population, and rising elementary and secondary enrollment have combined to increase the number of students willing and able to enroll at the tertiary level. Since 2000, Cameroon’s per capita GDP [30] has more than doubled, and today, more than 60 percent [57] of Cameroon’s population is under the age of 25. As a result, tertiary enrollment has expanded rapidly since 2000. By 2015, enrollment more than quintupled, increasing from around 66,000 [35] to more than 370,000.

The political instability of recent years reversed some of those gains. Following the Anglophone Crisis, enrollment declined sharply, falling 25 percent between 2015 and 2016 alone, as institutions in the two Anglophone regions were ordered to shut their doors. Enrollment has recovered slightly since, but in 2018, the latest year for which data are available, enrollment was still 11 percent below the 2015 peak.

While this rapid growth succeeded in expanding access to higher education, by international standards access remains restricted. In 2018 [196], Cameroon’s tertiary gross enrollment ratio stood at just 14 percent, well below the world average (38 percent). Regionally, its performance is more impressive—Cameroon’s tertiary GER is currently the highest in Central Africa [197], and well above the sub-Saharan African (9 percent) average.

Overall numbers also hide stark disparities in access by location and socioeconomic status. While 28 percent [194] of college-age Cameroonians from the richest quintile attended a higher education institution in 2018, less than 3 percent from the three poorest quintiles did. Around 15 percent of college-age individuals living in cities pursued higher education, but just 2 percent of residents from rural communities did so.

Cameroonians fortunate enough to attend and complete tertiary education face a different challenge: unemployment. Youth unemployment has been an issue in Cameroon since the 1990s. Although the situation improved rapidly in the early 2000s [199], university graduates still face poor employment prospects. In 2014, unemployment among those with at least some tertiary education stood at 13.3 percent [200], well above those with just a basic education (2.6 percent [201]). Graduates of the country’s Anglophone universities likely face even stiffer challenges securing employment. In many Francophone African countries, French proficiency is perceived favorably [202] and facilitates entry to the workforce. As mentioned above, a lack of post-graduation employment opportunities has also compelled many of Cameroon’s more qualified graduates to emigrate [40].

Part of the explanation lies in the quality of education received at universities; the university system has been criticized as inadequately preparing students for the job market. In 1998, a World Bank report [203] noted that Cameroon’s higher education system, “initially designed to produce personnel for the civil service, no longer conforms to the economy’s needs in the era of shrinking public services, nor to international best practices.”

The government has taken steps to address the issue of youth unemployment. In February 2017, President Paul Biya announced the launch of the Plan Triennal Spécial Jeunes [204] (PTS-Jeunes), or the Special Youth Triennial Plan, with the objective of helping Cameroonians between the ages of 15 and 34 to find rewarding jobs in agriculture, industry, and technology. Initial funding [205] was substantial, with US$189 million, or 102 billion CFA francs, earmarked for the plan in 2017. By 2020, in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, this three-year plan had financed 5,500 initiatives, before being renewed [206] by the Ministry of Youth and Civic Education (MINEJEC), the ministry entrusted with the program’s implementation.

Corruption also plagues Cameroon’s higher education system. Cameroon’s National Anti-corruption Commission [207] (CONAC), which in 2017 launched a campaign aimed at reducing incidences of fraud in schools [208] and universities, identified serious instances of corruption and fraud in the country’s higher education institutions, including “nepotism [209], counterfeiting of results, false diplomas, promotions in return for sex, and abuse of power.”

Many of the issues stem from underfunding. As mentioned above, government spending on education as a percentage of GDP in Cameroon is well below world and sub-Saharan African averages. And of the money the government does spend on education, little goes to higher education. In 2012, just .2 percent [85] went to higher education, compared with 1.4 percent for secondary education and 1 percent for elementary education. In fact, with government expenditure growing only around 28 percent [210] in constant U.S. dollars between 2004 and 2013, while tertiary enrollment grew around 284 percent, spending per student likely fell by as much as 67 percent over that time.

Higher Education Institutions

Higher education is still relatively young in Cameroon. From 1962 to the early 1990s, just one public university, the Université de Yaoundé, served the entire country. In 1993 [211], the government created four universities, splitting the University of Yaoundé in two, and establishing universities in Douala and Dschang. Since then, public universities have gradually expanded. Today there are eight traditional public universities, or universités d’etat, located in all but three regions, the North, South, and East Regions. A ninth, the Université Inter-États Cameroun Congo [212] (UIECC) opened in 2020 and is administrated by the governments of both Cameroon and the Republic of the Congo, with campuses located in both countries. Public universities continue to educate the majority of Cameroonian students [213], most of whom enroll in Francophone institutions and programs.

Cameroon’s public universities are large, multidisciplinary institutions offering undergraduate and postgraduate programs in a range of academic and professional disciplines. They are typically made up of faculties, technological institutes, and technical and vocational institutes. Two universities predominately serve Anglophone students, the University of Buea [214] in the Southwest, and the University of Bamenda [215] in the Northwest.

While public universities continue to educate the majority of the country’s students, the private higher education sector is growing rapidly. In fact, with government spending stagnant, private higher education institutions, or instituts privés d’enseignement supérieur (IPES), absorbed much of the skyrocketing demand for higher education that began in the mid-2000s.

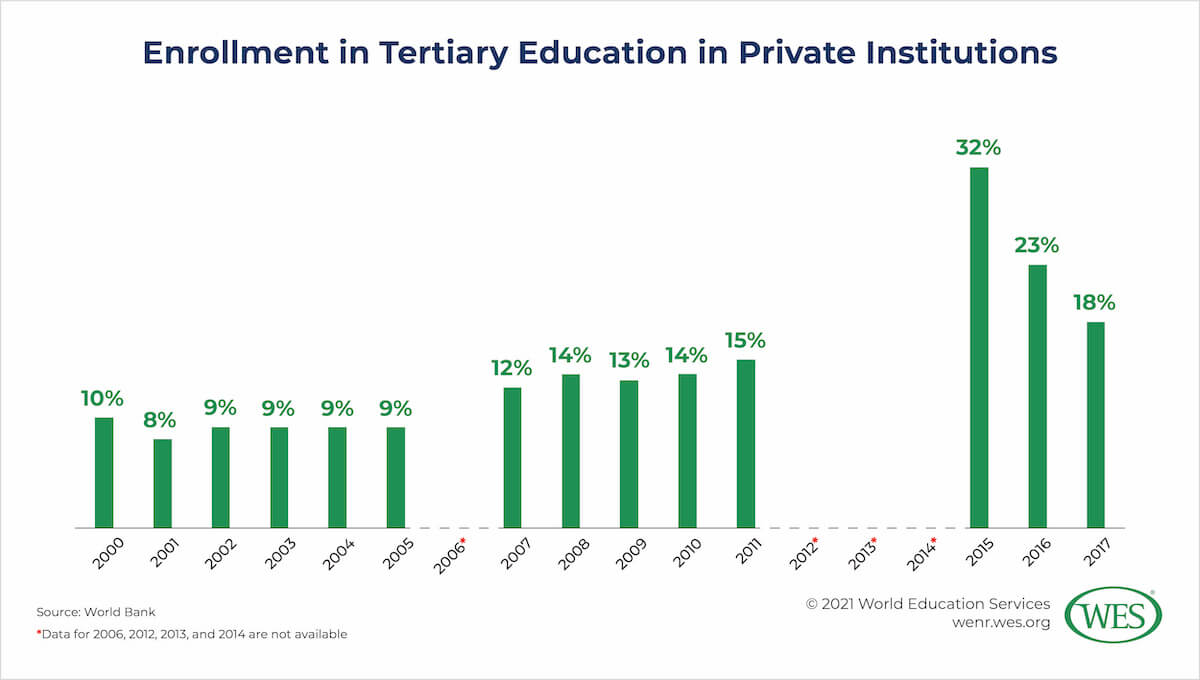

Extrapolations from UIS data reveal the extent of private sector growth, although MINESUP data [216] paint a slightly different picture. According to UIS data, in 2004, just 9 percent [213] of university students, or around 7,000 students, enrolled in private institutions. By 2015, that percentage had risen to 32, or about 118,000 students, more than 16 times the number enrolled in 2004. By comparison, enrollment in public universities in 2015 was just 3 times larger. More recently, private institutions have struggled to navigate the disruptions caused by the Anglophone Crisis—between 2015 and 2017, private enrollments fell by more than half.