[1]

[1]Schoolchildren tour a monument in Kraków commemorating Polish-Lithuanian victory over the Teutonic Order at the Battle of Grunwald in 1410. The event has come to symbolize Poland’s struggle against foreign invaders.

Education in Poland is in the midst of a radical transformation. Middle schools—previously the second stage of a three-tier, 6+3+3, school system—have been phased out. The length of the remaining two stages, elementary and secondary, have been extended, from six to eight and from three to four years, respectively. Reforms to vocational and tertiary education are also underway.

While these structural changes triggered an immediate flurry of protests from Polish students and teachers—who questioned, among other things, why an education system widely viewed internationally as a undisputed success needs to be reformed in the first place—as of publication, their status is more or less guaranteed. The major changes to the structure of the school system—first rolled out in 2017, just 10 months [2] after the respective legislation was passed—are on schedule for full implementation by 2022.

But other changes continue to spark controversy. Among the most divisive are changes to the curriculum [4] introduced by the ruling, national-conservative Law and Justice party (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, PiS). These changes trim coverage of certain subjects in science, such as the theory of evolution, while promoting nationalistic values and, in the words of the current education minister, “forgetting the ugly [5]” moments of the country’s past.

While some, such as the education minister, allege that such measures are necessary to end the “pedagogy of shame” that they believe currently pervades Polish academia, others are less sure. A director of a middle school in the suburbs of Warsaw, interviewed by the Financial Times [6], worried that the reforms were really aimed at creating a “new Pole.” “It’s about raising a human being who is obedient, xenophobic, traditionalist, extremely Catholic, without any European values.”

This conflict over the content of the curriculum reflects wider divisions in Poland today, where the enthusiasm that followed the collapse of communism and inclusion in the wider European community has often soured into hostility. As the ongoing educational reforms outlined below illustrate, these tensions, and the political landscape they helped shaped, have important implications for the current and future direction of the Polish education system.

Poland: A Post-Communist Success Story?

Like so many other post-communist countries, the contours of Poland’s current political landscape were shaped in the years that immediately followed the collapse of communism. In early 1989, constitutional changes that Poland’s long-ruling Communist Party and opposition groups agreed to paved the way for the country’s first semi-free elections. The Communist Party’s unexpected and overwhelming defeat in those elections later that year opened the way to the country’s transition from the communist Polish People’s Republic to the Western-style liberal democratic Third Polish Republic.1 [7]

Political change continued throughout the 1990s, culminating in the adoption of a new constitution [8] in 1997. This constitution confirmed many of the reforms introduced since the elections of 1989, guaranteeing civil rights and establishing a parliamentary democracy operating under a strict separation of powers between the president, the parliament, and the judiciary.

At the same time, Poland took steps to free itself from the influence of its powerful eastern neighbor, Russia. In 1991, the Warsaw Pact, a collective defensive treaty between the Soviet Union and other socialist states in Central and Eastern Europe, was dissolved [9]. Two years later, the last Russian troops [10] left Polish soil. Instead, Poland looked West, joining the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in 1999, over the objections of Russia, and acceding to the European Union in 2004.

Poland moved closer to Western Europe in the realm of education as well. In 1999, Poland replaced its two-tier, 8+4 elementary and secondary school cycle with a 6+3+3, elementary, lower secondary, and upper secondary structure. That same year, it became one of the first signatories of the Bologna Process, thereafter gradually introducing a raft of related reforms.

The fall of communism also brought with it a dramatic restructuring of the economy. Spurred in part by Western financial institutions, the new government introduced a radical package of economic reforms just months after the 1989 elections. The reforms, known as “shock therapy [11],” rapidly replaced the country’s controlled economy with a free market system. Almost overnight, price controls on consumer goods like bread and fuel were lifted, state-owned enterprises were sold off, and foreign trade restrictions were removed.

The changes made were to have profound, long-term effects, but in the short term, they led to a dramatic decline in the standard of living. Between 1989 and 1991 [12], Poland’s economy collapsed, with gross domestic product (GDP) falling by 7 percent in both 1990 and 1991. Prices for food and other goods skyrocketed—inflation reached over 550 percent [13] in 1990—while living standards declined. Unemployment, which was officially non-existent under communist rule, skyrocketed, rising to more than 16 percent [14] by 1994.

But, unlike the situation in many other post-communist countries, this instability, or at least some of it, proved short-lived. By 1992, the shock therapy reforms had managed to slash the inflation rate to under 50 percent. That same year, Poland’s economy began to sputter back to life, expanding again [15] for the first time since 1989.

Since then, Poland’s economy has been one of the fastest growing in Europe: Between 1992 and 2020, Poland’s GDP [16] increased nearly 450 percent. Globally, it has even outpaced [17] the Asian tiger economies, Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan. This growth has helped close the gap between the standards of living in Poland and those in the rest of Europe. Since 1992, per capita GDP [18] has grown from around 37 percent of the EU average to more than 75 percent. Poland’s economic performance was even strong enough to mitigate much of the devastation of the Great Recession: during the crisis, Poland was the only EU country to avoid a recession [19].

This economic growth has no doubt been powered by some of the educational and political changes introduced since 1989. Observers have credited reforms introduced in the late 1990s and mid-2000s with a dramatic turnaround in Polish education that saw learning outcomes at the elementary and secondary level improve from well below average to among the world’s best. Poland’s accession to the EU also undoubtedly contributed to its growth. Not only did membership remove trade barriers, it also made Poland eligible for EU development funds. Since joining, Poland has been the largest recipient [20] of the EU budget.

These achievements long made Poland a poster child for post-communist success. In 2014, they even prompted then-President Bronisław Komorowski to declare the last two decades of Polish history the country’s “second golden age [21].” But despite this enthusiasm, discontent in Poland was growing.

Poland B and the End of the Golden Age

In Warsaw and other cities in the country’s west, the decades since the fall of communism have seen booming development [22] and rising prosperity. But east of the Vistula River, in what is known informally as Poland B [23], the situation differed. For decades, housing [24] shortages, a scarcity of health care [25] services, and crime and corruption have plagued the east, although their effects can also be felt in towns and cities throughout the country. There, economic expansion failed to take off: Even today, Poland’s eastern provinces are among the poorest in the EU [26].

Conditions in the east paint a different picture of Poland’s post-communist experience, one of growing inequality—income inequality [27] in Poland today is among Europe’s highest—and declining opportunity. Despite more than two decades of economic expansion, unemployment in Poland remained above 10 percent [14] nationwide until 2015. Youth unemployment [28] has been even worse.

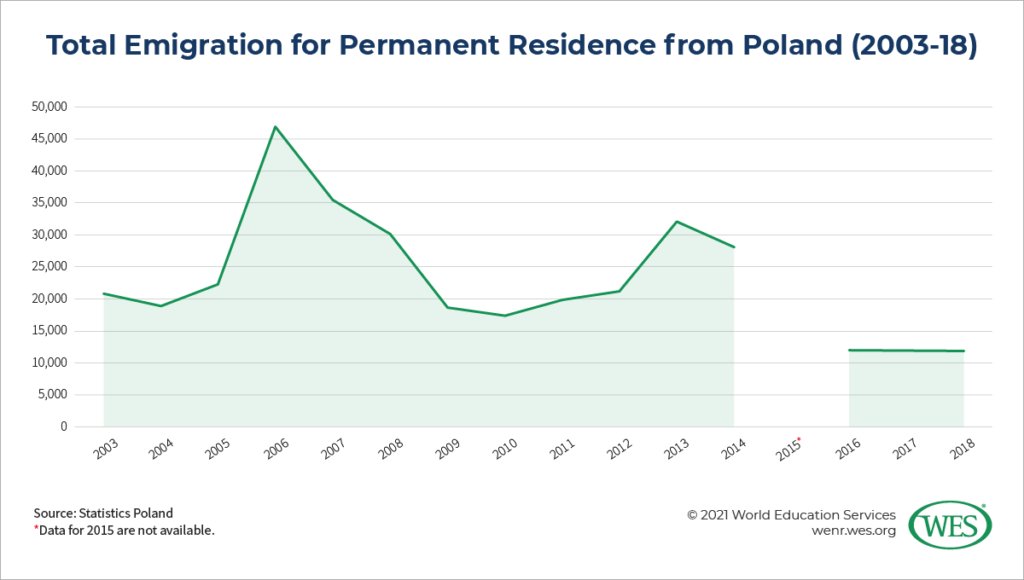

These conditions have helped drive a massive exodus of Poles from the country. While migration rates are highest in the east [29], unemployment and the allure of higher wages abroad have led millions of predominately young, highly educated Poles from all corners of the country to move elsewhere. A Gallup poll [30] in 2014 found that more than two in five Poles between the ages of 15 and 29 would permanently move to another country if given the chance. Another poll [31] that year found that fewer than 10 percent of Poles under the age of 34 had never considered leaving the country. In 2017, more than half a million [32] highly educated Poles lived in another EU country, the most of any country in the union.

While this immigration eventually eased unemployment and netted the country billions of euros in remittances [34], in the eyes of many it also severely strained the country’s social fabric. Emigration has starved the country of much-needed manpower. To take just one example: A 2017 report [25] by the European Commission noted that outmigration has contributed to the EU’s largest shortage of health care professionals. It has also created a generation of “Euro-orphans [35],” the children of Polish foreign workers left at home with relatives while their parents work abroad, and who, experts worry, are suffering significant psychological harm [36].

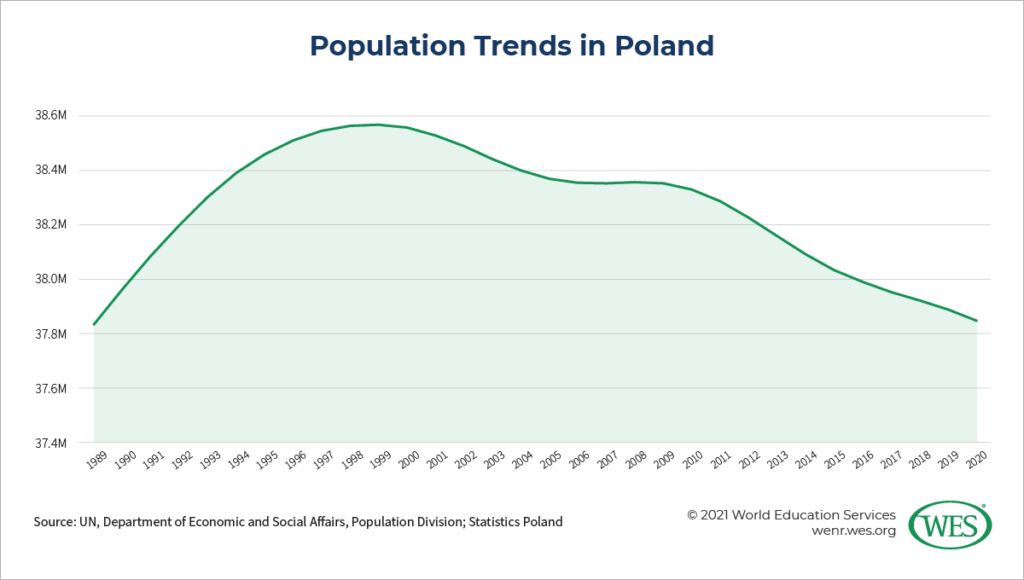

Immigration, along with declining births [37] among those who remained at home, has also contributed to the aging and shrinking of Poland’s population. Poland is among the fastest shrinking [38] countries in the world today. Since peaking in 1999, the country’s population has declined by around 2 percent. The UN estimates that it could contract by a further 39 percent [39] by the end of the century.

The concomitant aging of the population has been even more dramatic: Between 2005 and 2017, the post-working age population has grown from 24 percent [40] of the working-age population to 37 percent. As in other countries experiencing similar changes, these demographic shifts are expected to severely strain public services.

By the 2010s, after two and a half decades, these conditions had taken their toll. According to a poll conducted in 2014 [42], although a majority (53 percent) of Poles felt that the economy had improved since 1989, an even higher percentage felt that health care (62 percent) and the strength of family ties (54 percent) had declined. Higher percentages of those surveyed also believed that social security, readiness to help others, honesty, and religiosity in Poland had deteriorated. A year later, these sentiments proved fertile ground in which to nurture the growth of reactionary political movements.

The “Fourth Republic”: Law and Justice

Dissatisfaction with the post-1989 status quo came to a head in 2015.2 [43] In elections held that year, the same regions [44] left behind by the post-1989 growth powered PiS, a right-wing, Eurosceptic political party, to victory.

The elections marked the first time in Poland’s post-communist history that one party controlled both the presidency and the parliament—albeit aided by the quirks of Poland’s representational system—without coalition partners, giving PiS unprecedented control over the country’s political future. Once in office, the party didn’t hesitate to wield it.

Led by their powerful party leader, Jarosław Kaczyński, who currently holds no elected office, the new government has introduced a number of widely popular proposals, including sizable monthly child allowances [45] and the restoration of lower retirement ages [46], which the previous government had raised.

But most of its initiatives have been far more controversial. Since taking office, the government has pursued a highly nationalist and authoritian political agenda, introducing a near-total ban on abortions [47], encouraging the establishment of LGBT-free zones [48] across the country, and cracking down on the independence of the media [49] and the judiciary [50]. It has also refused to resettle Muslim refugees [51] and contested the legitimacy of key EU institutions [52].

PiS hasn’t spared the education system. Critics contend that since assuming office, PiS has used the education system to promote its national-conservative agenda. In the words of historians Jerzy Lukowski and Hubert Zawadzki:

The government’s cultural agendas in education, the media and the arts are directed at promoting what it would describe as wholesome traditional patriotic values and a positive, even a heroic, view of Polish history. All are serving to reduce the influence in Polish public life of the government’s internal enemies: secularists, liberals, critical intellectuals and cosmopolitans. Many of its critics accuse the government of creeping authoritarianism and of turning the country into ‘an illiberal democracy’ akin to Orbán’s Hungary. In such a climate, the nationalist far-right, although still a small minority, has become emboldened. Vociferous public expressions of xenophobia, including anti-Semitism, are not only proving to be divisive but also reviving memories of a darker past.3 [53]

Those fears have only intensified since the chaotic 2020 presidential elections, which narrowly returned the PiS candidate to office. The elections were followed by the appointment [54] of the controversial Przemyslaw Czarnek as Minister of Education, who just months earlier had commented: “Let’s protect ourselves against LGBT ideology and stop listening to idiocy about some human rights or some equality. These people are not equal to normal people.” Early the next year, Czarnek announced that the new Polish history curriculum will frame the EU is an “unlawful entity [5],” while focusing on “what is beautiful in our history.” The subsequent appointment of a deputy education minister accused of anti-Semitism [55], homophobia, and harboring fascistic tendencies, has only reinforced those fears.

Although Poland’s education system has made impressive strides since the fall of communism, today it faces numerous challenges. How can educational institutions at all levels manage an era of ever-shrinking enrollments? How can regulators address the excesses—such as a proliferation of low-quality private colleges—that followed the 1989 elections? And although PiS has already restructured the form of Polish education, it also remains to be seen just how far it can mold its character, and just how much resistance it will meet. While the COVID-19 pandemic has largely tempered hostilities, the massive strikes [56] that previously rocked the education system may provide an intimation of the future.

Outbound Student Mobility

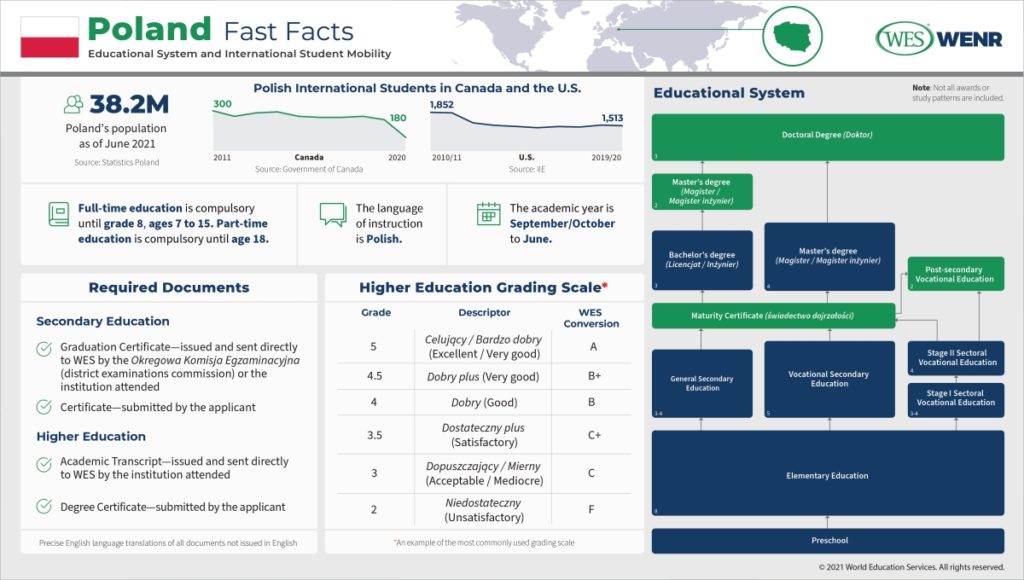

Poland’s accession to the EU in 2004 encouraged ambitious young Poles to head abroad not only for work, but also for school. Between 2004 and 2009, the number of Polish students studying internationally increased by an average of more than 7 percent per year, growing from 18,041 in 2004 to 28,500 in 2009, according to data from the UNESCO Institute of Statistics [57] (UIS).

But demographic changes and the onset of the Great Recession meant that growth was short-lived. Between 2009 and 2013, the number of Polish students studying abroad had decreased by about a fifth.

Since 2013, numbers have ticked up again, reaching 26,351 in 2018. But despite this growth, compared with total enrollment levels in Poland, relatively few Poles travel abroad for education. Polish outbound degree mobility is among the lowest [59] in the European Higher Education Area (EHEA): just 1.8 percent [60] of Polish tertiary students studied outside the country in 2018. Despite steady growth over the past five years, that percentage still trails both world (2.5 percent) and regional averages (3.5 percent in Europe and 2.3 percent in Eastern and Central Europe).

As in other eastern European countries [61], cost [62] is likely the most important factor in the decisions of young Poles not to study abroad. Compared with the cost of studying at home—where seats in high-quality, if not globally elite, public universities are readily available—fees abroad, even in other EHEA countries, are relatively high. Furthermore, unlike the situation in some other EHEA countries, the Polish government does not allow Polish students to use domestic financial support on full-degree programs in other EHEA countries, limiting it instead to short-term, credit-mobility programs [59].

Top Host Countries

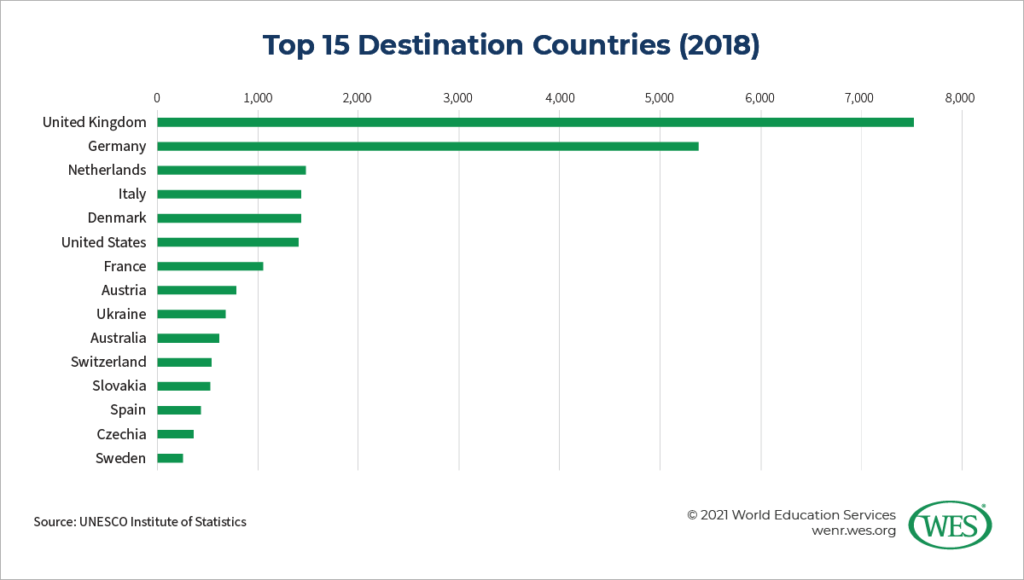

The top destinations for internationally mobile Polish students also hint at the importance of affordability in Polish enrollment decisions. Eleven of the 15 most popular destinations for Polish students are members of the EU, which means [64], with regard to tuition and other fees, that Polish students are treated the same as nationals.

Unsurprisingly, there was a modest uptick in the number of Polish students studying in most European states following Poland’s accession to the EU. But for the United Kingdom, that growth was dramatic. Between 2004 and 2005, Polish enrollment in U.K. higher education institutions increased by more than 125 percent. By 2009, when Polish student enrollment in the U.K. peaked at 9,144, the numbers had increased around 850 percent. The U.K.’s decision [65] to immediately remove restrictions on migration from Poland (and other eastern European states) in 2004—a decision unique among major EU host countries—helps account for some of this rapid growth.

But in the U.K., after that flurry of expansion, conditions began to change considerably for Polish students. A tuition hike at British universities in 2012, combined with restrictions on post-study work opportunities, resulted in a steep decline in Polish enrollments. By 2014, numbers had fallen to 5,184, a decline of 43 percent from their peak in 2009.

Although growth has since resumed—the U.K. hosted 7,520 Polish students in 2018—more pressing obstacles now confront them. Observers have long expected the British withdrawal from the EU—an action determined in part by a popular backlash to immigrants [66]—to severely impact the U.K.’s appeal as a study destination to students from EU nations. While the full impact remains to be seen, early reports [67] suggest they could be severe. By the end of June 2021, applications from Poland had fallen [68] by 73 percent from their level a year before.

Germany is the second most popular destination for internationally mobile Polish students. In 2018, 5,379 Polish students were enrolled in German universities, a level that has remained more or less constant for the past several years. Besides its proximity and high-quality universities, Polish students are likely attracted to Germany by its close economic and social relations with Poland: Germany is Poland’s largest trade partner [69] by far and hosts more Polish immigrants [70] than anywhere else in the world.

Other European countries, notably the Netherlands (1,476), Italy (1,431), and Denmark (1,431) have also grown in popularity in recent years. On the other hand, France, once one of the most popular destinations for Polish students, has gradually fallen out of favor since the mid-2000s. In 2004, France hosted 3,427 students from Poland—18 percent of all international Polish students. By 2018, these numbers had dwindled to 1,051, just 4 percent of all Polish international students.

Polish Students in the U.S. and Canada

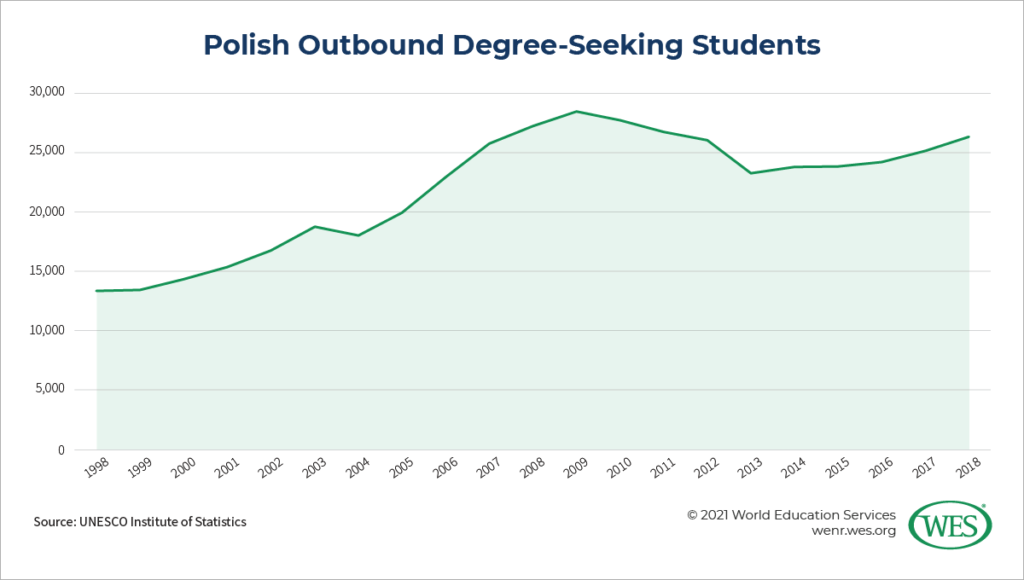

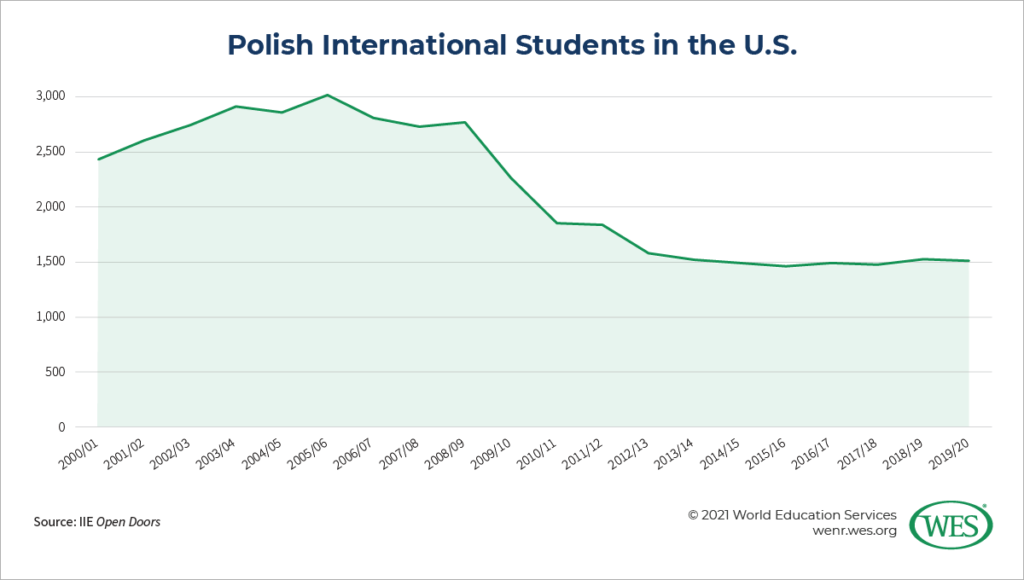

Outside of Europe, the United States is by far the most popular destination for Polish students. According to data from the Open Doors report [71], a resource of the Institute of International Education (IIE), 1,513 Polish students were studying in the US during the 2019/20 academic year, a level that has remained remarkably steady since 2012/13.4 [72]

But, as in France, Polish enrollment in the U.S. was once much higher. Enrollment peaked at nearly twice its current level in the 2005/06 academic year, when it reached 3,020 and the U.S. was the third most popular study abroad destination, behind just the U.K. and France.

Enrollment declined rapidly in the years following the financial crisis, which caused the value of the Polish złoty to decline sharply against the U.S. dollar. Besides the impact of the economic downturn, a 2015 EducationUSA report [74] identifies the rising cost of U.S. higher education and the increased attractiveness of institutions in other EU countries as drivers of the fall in enrollment.

Of those Polish students who do come to the U.S., a relatively high proportion enroll in undergraduate programs. In 2019/20, 47 percent [75] were studying for a U.S. undergraduate degree, compared to 42 percent of all European students and 39 percent of all international students. That same year, 29 percent were enrolled in graduate programs and 10 percent in non-degree programs. A further 13 percent participated in the Optional Practical Training (OPT) program—a proportion far smaller than found among total international students (21 percent), but roughly on par with those from Europe (14 percent).

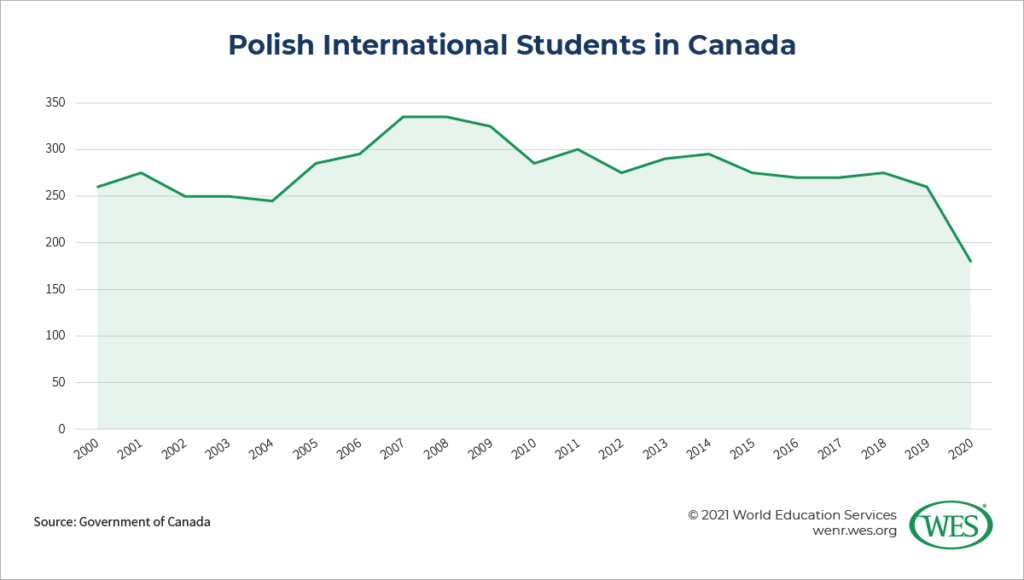

Polish mobility to Canada is far more subdued. According to data [76] from Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), since 2000, no more than 335 Polish students (a level achieved in both 2007 and 2008) have ever held a valid study permit in any given year.

Predictably, the pandemic further depressed those numbers. In 2020, Polish enrollment in Canadian institutions fell to a twenty-first century low, with just 180 Polish international students holding a study permit by the end of that year. While monthly data [78] suggest that those numbers may rebound slightly in 2021, in the long term, Canada faces many of the same problems as the U.S. when it comes to attracting Polish students.

Inbound Student Mobility

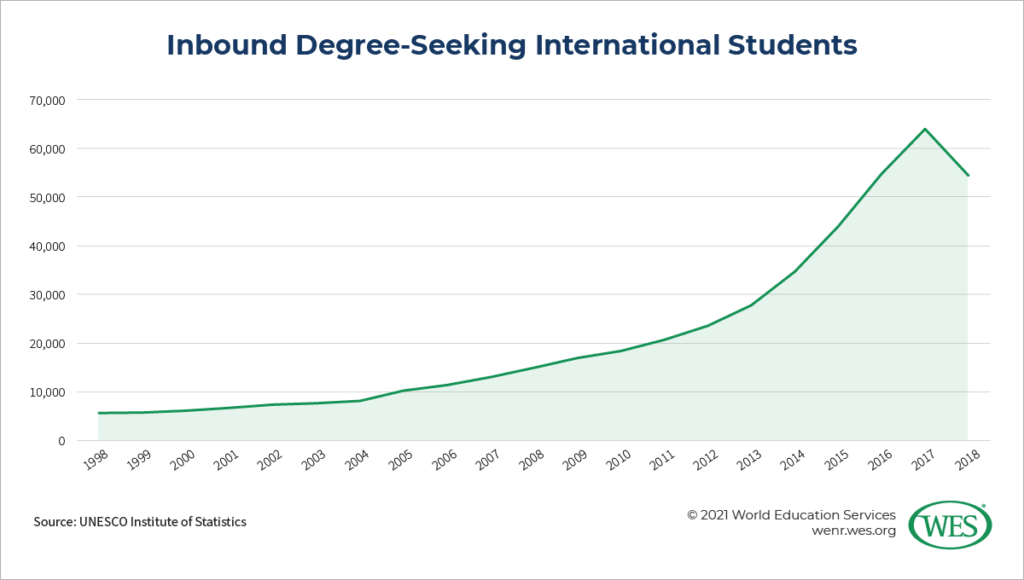

Historically, Poland has not been a popular destination for international students. In recent years, however, the country’s shrinking domestic student population has convinced the government of the importance of international students. In 2015, the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education (Ministerstwo Nauki i Szkolnictwa Wyższego, MNiSW) introduced an ambitious internationalization program [79] aimed at doubling the number of international students studying in the country from less than 50,000 to 100,000 by 2020 [80]. To meet this goal, the ministry pledged to finance the creation of more international doctoral and post-doctoral programs and foreign language degree programs, among others. Additionally, the ministry encouraged Polish universities to team up with foreign educational institutions and hire more international faculty and lecturers.

Other initiatives have since followed. In 2017, the government established the National Agency for Academic Exchange [81] (Narodowa Agencja Wymiany Akademickiej, NAWA) to coordinate the government’s support for international student and scholar mobility and exchange and internationalization at the country’s higher education institutions. NAWA currently manages a number of scholarship and exchange programs [82] for non-Polish students and runs the government’s “Ready, Study, Go! Poland” campaign [83] which promotes Polish higher education throughout the world.

These reforms have been successful. Between 2015 and 2018, Polish universities doubled [84] the number of courses taught in English [85] on offer. Polish higher education institutions also enrolled more international students in short- and long-term programs. During the 2020/21 academic year, Polish institutions enrolled 84,672 international students, an increase of over 84 percent since the end of the 2014/15 academic year, according to figures [86] released by Study in Poland.

But other measures paint a slightly different picture. According to UIS data [87], which does not count international students on short-term mobility programs, the number of international degree-seeking students in Poland peaked at 63,925 in 2017. The next year it fell to 54,354, a decline of around 15 percent.

Poland’s inbound mobility rate remains relatively low as well. Despite growing quickly in recent years, Poland’s inbound mobility rate [89] stood at just 3.6 percent in 2018, one of the lowest in Europe. In nearby countries, such as Slovakia (8 percent), Germany (10 percent), Hungary (11 percent), Czechia (14 percent), and Austria (17 percent), inbound mobility rates are more than twice as high.

Top Source Countries

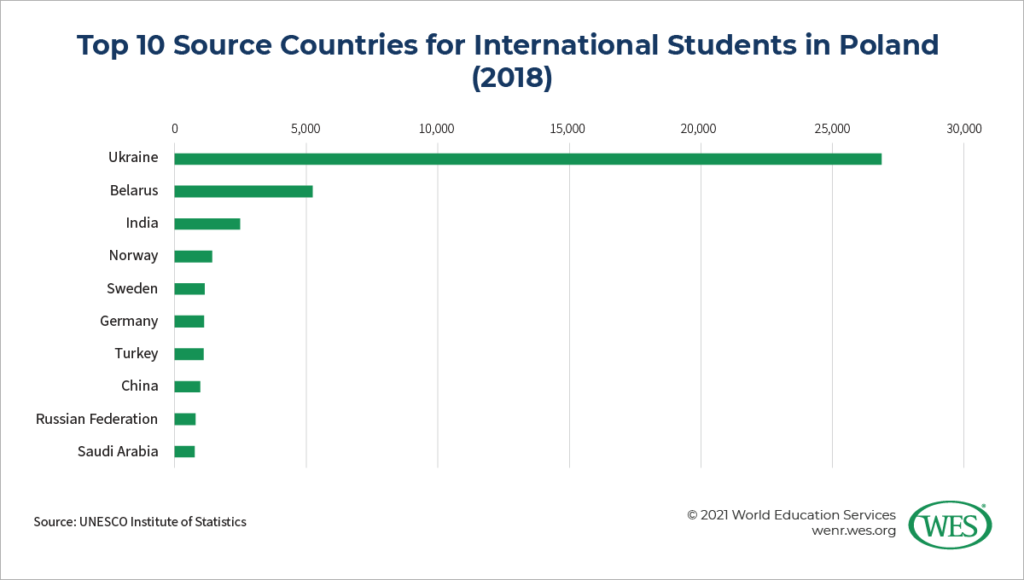

Ukraine is by far the largest source of international students in Poland. In 2018, the nearly 27,000 Ukrainian students in the country made up nearly half of all its international students, according to UIS data [91]. Although the ongoing military conflict in eastern Ukraine drove a sharp uptick in enrollment [92], Ukrainian students have long flocked to Polish universities. In fact, Ukraine has been the largest source country of international students in Poland for the past 20 years.

Ukrainian students are attracted to Poland for a variety of reasons [92]. Besides Poland’s proximity and relatively inexpensive tuition fees and cost of living, Ukrainian students value the ability to earn a European degree as a stepping-stone to further employment in the EU.

Furthermore, the Polish government has made recruiting students from Ukraine and Belarus—long the second-largest source of international students in Poland—a priority. It funds a number of exchange programs for students from these countries, including Polish Erasmus for Ukraine [93] and Solidarity with Belarus [94]. The government’s motivations are largely political. Both countries are members of the Eastern Partnership [95], a project spearheaded by Poland and Sweden to draw former Soviet republics away from Russia and toward the EU.

But there are signs that interest in Polish universities may be waning, at least among Ukrainian students. As Ukraine’s economy has improved, its labor market has tightened, a development that has led some observers to predict [96] that more Ukrainians will look for work at home rather than abroad. Also notable is growing competition from Germany for Ukrainian workers. In early 2020 Germany eased labor regulations [97] in a bid to attract laborers from outside the EU. The Polish National Bank estimates [98] that the new regulations could encourage a quarter of the Ukrainian workers already in Poland to head for Germany. Combined with the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic—Poland issued 44 percent [99] fewer visas to Ukrainian nationals in the first half of 2020 than in same period in 2019—these factors could lead to a sharp decline in Ukrainian enrollment in Polish universities. That decline may already have begun: Between 2017 and 2018, Ukrainian enrollment in Poland fell by more than a fifth (23 percent).

Far fewer students from other countries study in Poland. India—the third-largest source of international students—sent 2,497 in 2018, according to UIS data [91]. Although low compared with Ukraine’s student numbers, India’s 2018 figures represent a large increase over past years. In 2016, just 914 Indian students studied in Poland.

With demand for a medical education [100] far exceeding the supply of seats in India, many of these students enroll in medical programs in Poland. They’re not alone. In recent years, the simple admission procedures, relatively low cost, and perceived quality of medical education in Poland has made the country a popular destination for international students hoping to study medicine [101].

Students from other European countries—such as Norway, Sweden, and Germany—are also attracted by Polish medical programs. According to a report [102] from the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD), over two-thirds of German students in Poland were enrolled in health and welfare programs in 2017. The report surmises that stringent admission requirements for medical programs in Germany combined with the high quality of Polish medical education make Poland an attractive study destination for German students.

More recently, Poland has been trying to attract students from Kazakhstan [103], which is the seventh-largest source of international students in the world. In 2018, the presidents of the Conference of Rectors of Academic Schools in Poland and the Council of Kazakhstan Universities’ Rectors signed a cooperation agreement [104] to foster academic exchange between the two countries. NAWA and other Polish educational organizations have also sent delegations [105] to academic fairs in Kazakhstan to promote Poland as a study destination for Kazakh students. As a result, the number of Kazakh students in Poland has grown slowly but steadily—rising from 369 in 2011 to 650 in 2018, according to UIS data [91].

In Brief: The Education System of Poland

[106]

[106]The Collegium Maius at the Jagiellonian University. The current building dates to the late fifteenth century.

Education has a long history in Poland. The country’s first university, currently known as Jagiellonian University [107], was founded in 1364 by the king to train competent administrators, focusing initially on law. Even earlier, provincial schools had begun to open. Run by religious orders, these schools provided a traditional liberal arts education to the country’s political, military, and mercantile elites. Jesuit institutions spread particularly quickly. By 1773, when the papacy abolished the order (temporarily, as it turned out), Jesuits ran 66 secondary schools and countless parish schools throughout the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.5 [108]

The papal decision to suppress the Jesuits opened the door to one of modern Europe’s earliest experiments in the secular control of education. The same year, parliament established the Commission for National Education, which assumed control of the institutions formerly run by the Jesuits. Granted wide-ranging authority, the commission set out to modernize education throughout the country, rationalizing the country’s disjointed network of schools and introducing Enlightenment ideas and principles into the curriculum. Although short-lived, the influence of the Commission, today recognized as Europe’s first Ministry of Education, has been long-lasting. Polish scholars [109] today widely acknowledge that the Commission’s activities laid the foundations for the survival of the Polish language and culture during more than a century of external rule.

By 1795, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth had been entirely partitioned between Austria, Prussia, and Russia [110], and both the Commission and the Commonwealth had effectively ceased to exist. For more than a century, these three imperial powers determined educational policy in the Polish lands under their control. While policies varied over time and place, in general, all three imperial authorities were united in their opposition to education in the Polish language, ordering that it be replaced with either German or Russian.

The long years of partition exacerbated regional educational disparities. While the introduction of compulsory elementary education (in German) nearly eliminated illiteracy in Prussian Poland by 1900, in Austrian and Russian Poland, access and achievement lagged significantly. By the end of the nineteenth century, less than a third of children in Austrian Poland were enrolled in elementary education, while in Russian Poland, nearly two-thirds of the population were still illiterate.6 [111] Although the imperial borders have long since disappeared, many of the disparities remain. Even today, educational achievement, economic output, and even political views continue to vary widely across the old imperial borders.

Poland finally regained its independence at the end of the First World War, as all three occupying empires collapsed. In the following two decades, the Polish government leaned heavily on the education system to instill a sense of national unity. It funded the expansion of the country’s network of elementary and secondary schools, and to a lesser extent higher education institutions. By the time of Germany’s invasion in 1939, these efforts had reduced illiteracy throughout the country to just 15 percent.7 [112]

After the Second World War, the influence of imperial powers in Poland again grew. Although spared outright annexation, Poland remained a tightly controlled satellite of the Soviet Union for more than four decades. During that time, the education system was overhauled in an attempt to reshape the minds of the country’s population. Administration was tightly centralized, religious instruction was quickly banned, and academic freedom was sharply curtailed. In classrooms throughout the country, courses in Marxist-Leninist ideology and the Russian language were made compulsory.

Education in Poland Today

Later events were to show the ineffectiveness of efforts to reshape the minds of Poland’s children. In 1989, partially free elections led to the overwhelming defeat of Poland’s long-ruling Communist Party, inaugurating a new era in Polish education.

Changes to the education system made in the 1990s and 2000s were largely aimed at aligning Poland’s education system with the EU. Poland was among the initial signatories of the Bologna Declaration [113] in 1999; in 2010, it became one of the earliest members of the European Higher Education Area (EHEA) [114]. In line with wider European projects [115], Poland also adopted a Lifelong Learning Strategy [116], aimed at ensuring that education would be available to all its citizens at every stage of their life.

Significant domestic reforms accompanied this realignment. Poland legalized the establishment of private educational institutions, embarked on a partial administrative decentralization, and gradually expanded the autonomy of teachers and professors. Poland also quickly introduced Bologna-style first- and second-cycle programs as well as external examinations to assess the competence of students at general and vocational secondary schools. In 1999, Poland also revised the structure of school education, replacing the 8+4 model with a 6+3+3 model.

Since the victory of the PiS in the 2015 elections, reforms have moved in the opposition direction, with changes to the elementary and secondary curricula highlighting the heroic achievements of Poland’s past and minimizing topics at odds with PiS ideology. At the higher education level, reforms introduced in 2018 changed the composition of university councils in a way that critics contend [117] will increase the ability of politicians to interfere in university affairs.

Other changes have been more politically mundane. Besides the reintroduction of an 8+4 model at the elementary and secondary level, they have brought vocational education into closer alignment with the country’s formal education system and the needs of employers. Other reforms have revised the national standards for doctoral programs and the institutions that offer them.

Administration of the Education System

Since 1999, Poland has been divided into three principal administrative levels [118]: 16 provinces or voivodeships (województwa), 314 districts (powiaty), and 2,478 communes (gminy). Provinces, the highest-level division, are administered by governors appointed by the prime minister.

Reforms have partially decentralized the administration of education. Currently, local authorities assume primary responsibility for establishing and administering [119] schools offering pre-elementary to secondary education: communes for nursery and elementary schools and districts for secondary schools. Provinces, through Regional Education Authorities (kuratorzy oświaty), supervise teaching methods and practice at these schools.

The central government and its subsidiary agencies develop and coordinate national education goals and policies. Until recently, two central educational ministries shared these responsibilities: the Ministry of National Education (Ministerstwo Edukacji Narodowej, MEN), which supervised preschool, elementary, secondary, and vocational education; and the Ministry of Science and Higher Education (Ministerstwo Nauki i Szkolnictwa Wyższego, MNiSW), which oversaw higher education, including scientific research and the training of doctoral students.

However, at the start of 2021, these two ministries were merged into a single entity, the Ministry of Education and Science [120] (Ministerstwo Edukacji i Nauki, MEiN). Two subunits of MEiN, the Department of General Education (Departament Kształcenia Ogólnego, DKO) and the Department of Higher Education (Departament Szkolnictwa Wyższego, DSW), assumed the responsibilities of the two previous ministries. The government hopes that the consolidation will reduce bureaucratic hurdles, increase efficiency, and promote intradepartmental collaboration and coordination.

The central government is also the primary funder of education, providing about 89 percent [121] of funding at the elementary and secondary level and 81 percent at the higher education level, both well above OECD averages [122]. As a result, although regulations permit the establishment of private institutions, public institutions tend to dominate the educational landscape. At the elementary and secondary levels, public schools vastly outnumber private schools and enroll the majority students. At the higher education level, while private institutions outnumber public, public institutions enroll more students overall and are typically viewed more positively by the general population.

Academic Calendar and Language of Instruction

Education is a right guaranteed to every individual and enshrined in Poland’s constitution. For children between the ages of 7 and 15, nine years of full-time education, or education conducted in a formal school setting, are compulsory [123]. Currently, that means that all students must complete one year of preschool education and eight years of single-structure elementary education.

Since 1999, part-time education or training for those between the ages of 15 and 18 has also been compulsory. Part-time education can be conducted in both school and non-school settings, including, for example, workplace training provided by an employer. The requirement that individuals continue education in at least some form until age 18 differentiates Poland from most other EU countries, where compulsory education often ends [124] at age 15 or 16.

The elementary and secondary school year [125] in Poland begins in September and ends in June, and is usually divided into two semesters. At the higher education level, the academic year [126]—which also typically consists of two semesters—often begins in October and ends in June.

As a result of the upheavals and forced population transfers of the Second World War and its aftermath, the population of Poland—once the center of a large, multi-ethnic empire—today is largely homogenous in terms of ethnicity, religion, and language. More than 90 percent [127] of the country’s population is Roman Catholic—the percentage [128]s declaring themselves Polish (97 percent) and speaking the Polish language (98 percent) is even higher.

Unsurprisingly, Polish is prescribed as the language of instruction [129] at all almost all levels of the educational system. Still, minority communities, many with roots in Poland extending deep into the country’s past, do exist. The government recognizes [130] more than a dozen minority communities to which it guarantees the right to instruction in their language and an education in their history and culture in formal school settings. These communities can establish bilingual elementary and secondary schools which offer courses conducted in both Polish and a minority language. Although Polish-language schools far outnumber all others, national regulations also allow for the establishment of bilingual schools, which offer instruction in Polish and a modern foreign language [131], and international schools, which follow a foreign curriculum and teach entirely in a foreign language.

At the higher education level, regulations also allow institutions to offer some or all courses in a given program in a language other than Polish [132].

Early Childhood Education (ECE)

Early childhood education (ECE) in Poland is divided into two stages: one for children aged between 20 weeks and 3 years, the other for students between the ages of 3 and 6.

ECE enrollment for children under the age of 3 is voluntary and, since October 2020, administered by the Ministry of Family and Social Policy [133]. Despite rapid growth in the number of places available at ECE institutions [134] for children below the age of 3, demand still far exceeds supply. Just 13 percent of children under the age of 3 were enrolled in ECE institutions in 2018. These figures trail well behind those of other OECD countries. For example, in 2018, the average OECD ECE enrollment rate for children aged 2 was around 46 percent [135]. That same year in Poland, it was just 7 percent.

Enrollment in the second stage of ECE is far higher than in the first stage. Currently, around 90 percent [136] of children in Poland between the ages of 3 and 6 are enrolled in preschool education. Although enrollment rates are high overall, many rural areas still lack adequate preschool facilities. While 95 percent of urban area children between the ages of 3 and 5 are enrolled in preschools, just 81 percent of those from rural areas are.

Recent regulations have helped boost enrollment rates. Since September 2017, all 6-year-old children have been required to attend one year of preschool. Although earlier enrollment is voluntary, communes are required to guarantee that all children between the ages of 3 and 6 have access to a preschool institution if so desired, either by establishing and administering a preschool institution itself or inviting non-public entities to establish preschool institutions funded from the commune’s budget.

Although private funding plays a more important role in ECE than at other levels of education, public schools still dominate. Around three-quarters of Polish children between the ages of 3 and 5 are enrolled in public institutions, slightly above the OECD average (around two-thirds).

Several different types of institutions deliver this stage of preschool education. The most common are nursery schools (przedszkole) and preschool classes (oddziały przedszkolne) located in elementary schools. These institutions provide at least five hours of ECE per day free of charge to children between the ages of 3 and 5; education for 6-year-olds is free no matter the duration.

All preschool institutions are required to follow the national core curriculum for preschool education. The curriculum seeks to promote the physical, emotional, social, and cognitive development of children [137] through structured periods of play, learning, and leisure, and prepare children for the first year of elementary education. Since the start of the 2017/18 school year, all preschool children begin to learn a foreign language [131]. Although MEiN develops this core curriculum and determines nationwide ECE policy, communes, the lowest administrative level in Poland, are responsible for the management and administration of nursery schools in their jurisdiction. Currently, children completing one mandatory year of preschool education automatically progress to the first grade8 [138] of elementary education.

Elementary and Secondary Education

Polish elementary and secondary education has changed dramatically since 1989. In 2000, Polish 15-year-olds ranked well below the OECD average on all three subjects assessed on the Program for International Student Assessment [139] (PISA). On the same assessment [140] almost two decades later, Polish students scored among the top 10 in reading and mathematics, and among the top 20 in science. Researchers [141] have credited these dramatic improvements to the reforms introduced in the late 1990s, which included, as mentioned above, the replacement of the school system’s 8+4 structure with 6+3+3 (6 years of elementary, 3 years of lower secondary, and 3 years of upper secondary) structure.

The strength of Poland’s education system has made the recent reintroduction of the 8+4 model controversial, even when viewed in isolation from the curricular changes that accompanied them. In 2016, as the reforms were being debated in Parliament, nearly 100 representatives of Polish universities [142] sent a letter to the education minister expressing their worry that the reforms would “squander the most important educational ideas developed after 1989.” These academic leaders contended that the change was introduced far too rapidly and chaotically and without adequate stakeholder and expert consultation. Others [143] have also criticized the government for the high cost of the reform (estimated at 900 million złoty or about US$225 million) and their impact on the country’s teachers: Around 9,000 teachers [144] were dismissed when lower secondary schools closed.

Despite these concerns, the reforms have largely continued apace. They’re expected to be largely completed by the start of the 2022/23 school year.

Elementary and Secondary Reform Details and Timeline

The reforms passed by the Polish Parliament at the end of 2016 have rapidly reshaped the Polish education system. At the start of the 2017/18 school year, the first grade of what was then lower secondary education was abolished, replaced by the seventh year of the extended, eight-year single-structure elementary education cycle. Just one year later, at the end of the 2018/19 school year, the last cohort of lower secondary school students had graduated, and all three-year lower secondary schools were closed.

At the start of the 2019/20 school year, new four-year general secondary schools were opened, and the old three-year upper secondary schools began to be gradually phased out. The last cohort of the old pre-reform upper secondary schools will graduate from three-year upper secondary schools at the end of the 2021/22 school year. A year later, in 2022/23, the new post-reform secondary schools will graduate their first class.

The reforms have also affected vocational secondary education. At the start of the 2017/18 school year, four-year technical upper secondary schools were transformed into five-year technical secondary schools [145] (technikum) and three-year basic vocational schools (zasadnicza szkoła zawodowa) into three-year stage I sectoral vocational schools [146] (branżowa szkoła I stopnia). Two-year stage II sectoral vocational schools (branżowa szkoła II stopnia), for students completing stage I, were introduced in 2020/21.

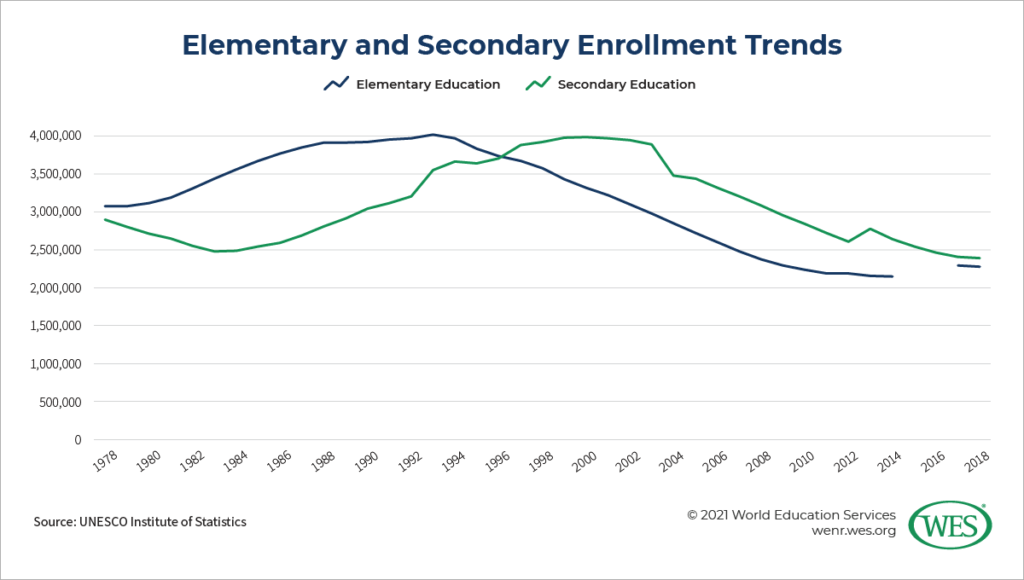

These new, post-reform elementary and secondary schools will enroll an ever-shrinking number of students. School enrollment in Poland has been declining for decades. By 2018, both elementary and secondary enrollment had declined by over 40 percent [147] from their peaks in 1993 and 2000, respectively. Given current projections of Poland’s population growth, those numbers are likely to continue declining for the foreseeable future.

Single-Structure Elementary Education: Integrated Elementary and Lower Secondary

Although school starting age has varied over the past several decades, today all children must begin elementary education [149] (szkoła podstawowa) at age 7 after completing a compulsory year of preschool education, although parents can apply to have their child admitted to the first year of elementary education at age 6, provided their child’s preschool teacher deems the child ready. All eight years of elementary education are compulsory and available free of charge at public elementary schools.

The national core curriculum at the elementary level is divided into two stages.9 [150] Stage I, known as early school education, comprises grades I to III and aims at developing pupils holistically. Instruction is typically provided by a single generalist instructor who is responsible for teaching a single class of students all compulsory subjects.

Stage II, which comprises grades IV to VIII, is subject based and focuses on reading comprehension and foreign language proficiency. The curriculum [151] for stage II currently includes biology, chemistry, civic education, computer science, geography, history, mathematics, modern foreign language, music and art, natural sciences, physical education, physics, the Polish language, safety education, and technology.

Regulations currently allow the educators teaching these subjects a wide degree of latitude in selecting teaching methods and classroom aids. They also allow teachers to select from a list of ministry-approved textbooks, which are provided to all pupils free of charge.

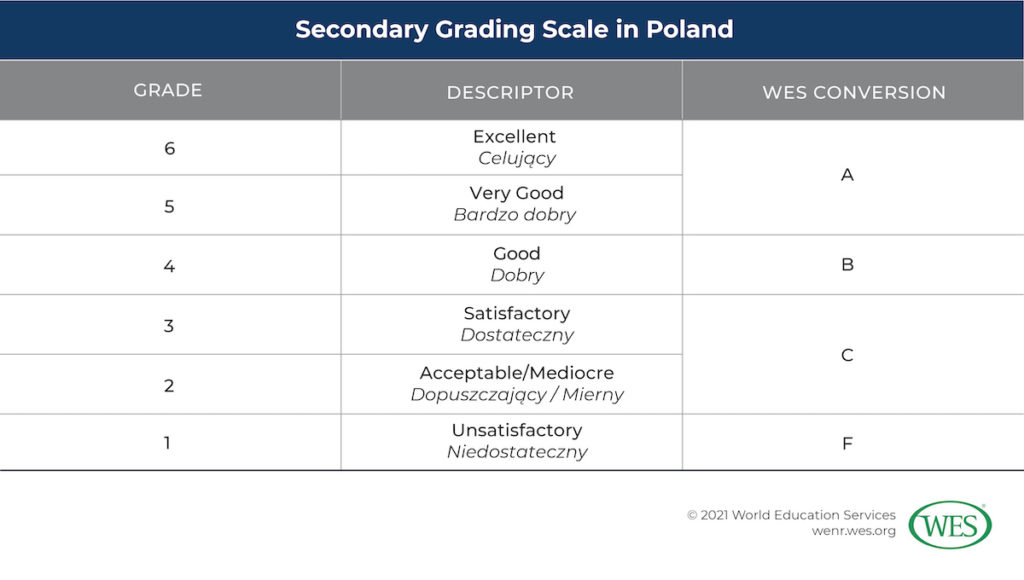

Academic progression varies by stage. Students in stage I automatically progress from one grade to the next. In stage II, however, students must receive marks higher than unsatisfactory (see grading scale below) in all compulsory subjects to advance to the next grade.

After completing grade VIII, students sit for an external examination, known as the eighth-grader exam. Introduced for the first time in the 2018/19 school year,10 [152] eighth-grader exams have no impact on a student’s academic progression. They do, however, play an important part in admission to post-primary schools. Eighth-grader exams also help to inform teachers and parents of student achievements.

Students completing elementary education receive a Primary School Leaving Certificate and a certificate issued by the Regional Examination Board indicating the results achieved on the eighth-grader exam.

General Secondary Education

Students completing elementary school can choose to enroll in one of two secondary streams: a four-year general, or academic, secondary stream, or a five-year vocational secondary stream.

The post-reform general secondary curriculum [153] includes the following compulsory subjects: biology, chemistry, civic education, computer science/IT, geography, history, introduction to entrepreneurship, mathematics, physical education, physics, the Polish language, safety education, and two modern foreign languages. School directors also choose one of the following: philosophy, visual arts, music, or Latin and ancient culture.

These subjects are taught at both basic and advanced levels. Although courses are only compulsory at the basic level, students often select two or three subjects from those listed above to study at the advanced level. Students are also able to choose from a handful of electives, including family education, minority language, history, culture, and religion or ethics, among others.

As at the elementary level, teachers are able to select teaching methods, classroom aids, and textbooks from among those approved by MEiN, although at the secondary level, the costs of the latter are borne by the students and their families. Provided they meet the learning goals outlined in the national core curriculum, secondary school teachers can also develop or adapt the curriculum to match the abilities of their students.

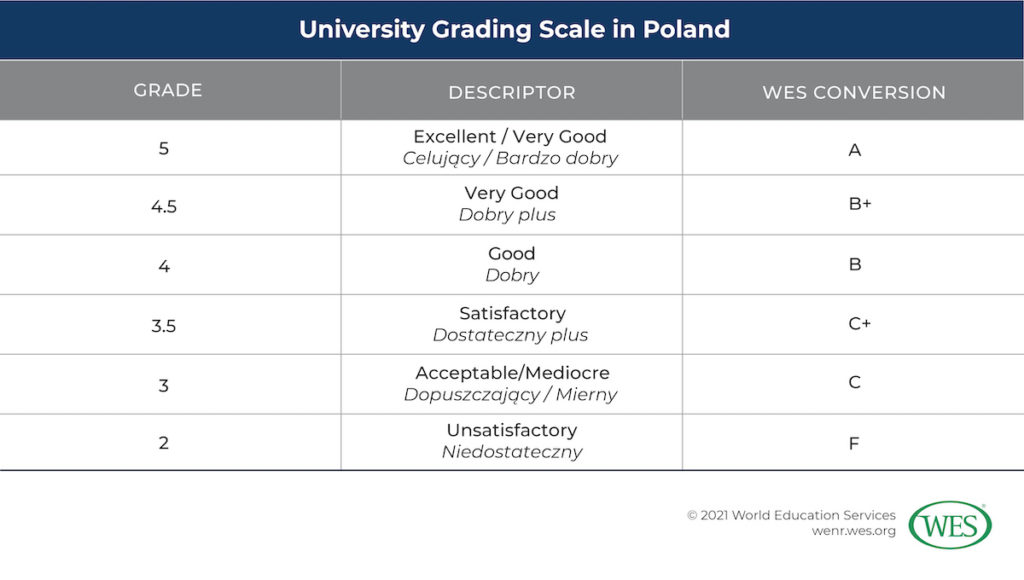

Students are typically graded on a six-point grading scale. Students must receive a grade of 2 or higher in all compulsory subjects to advance to the next grade.

Students successfully completing secondary education are awarded a school leaving certificate (świadectwo ukończenia liceum ogólnokształcącego), which indicates the subjects obtained by the student in the final grade of secondary education.

Students earning a secondary school leaving certificate are eligible to sit for the maturity exam (egzamin maturalny), which while not mandatory, is a requirement for admission to universities. Administered by the Central Examination Board (Centralna Komisja Egzaminacyjna), the maturity exam [155] consists of written and oral sections. All students must sit for basic-level exams in mathematics, a modern foreign language, and Polish.11 [156] They also choose between one and five subjects at the advanced level. Higher education institutions often specify in advance the subjects that will be used to determine admission to a given program, allowing interested students to select the relevant subject exams. To pass the exam, students must score at least 30 percent in each compulsory subject. Students are able to retake subjects to improve their score.

Students passing the maturity exam are awarded a maturity certificate (świadectwo dojrzałości) by the relevant Regional Examination Board. The maturity certificate indicates the results achieved by the student in both written and oral subjects. Students obtaining a maturity certificate are eligible to apply to higher education institutions and programs. While graduates with a school leaving certificate alone are not eligible to enroll in a higher education institution, they are able to access certain post-secondary vocational programs.

Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET)

As in other sectors of the country’s education system, reforms introduced over the past decade have transformed technical and vocational education and training (TVET) in Poland. Mirroring the structural changes made to elementary and general secondary education, recent reforms have introduced new vocational qualifications and institutions. Others have linked the TVET system more closely to the national qualifications framework.

One of the most significant reforms in recent years is the integration of vocational qualifications and diplomas into a comprehensive system of occupations. Under this system, vocational schools prepare students to take vocational examinations (egzamin zawodowy [157]). Students passing these examinations are awarded a vocational qualification [158], of which there are more than 250, which verifies their mastery of a defined set of skills. Possession of one or more of these vocational qualifications is required to obtain a diploma in one of the roughly 200 occupations defined in the classification of occupations [159].

After a student obtains all the qualifications identified as necessary to practice an occupation, they are awarded a vocational diploma, with the title of technician, in that occupation. Both vocational qualification certificates and vocational diplomas are issued by the Regional Examination Boards. Students can study for vocational examinations in both secondary and post-secondary TVET institutions.

Secondary Vocational Study

Secondary vocational education is very popular in Poland. The OECD’s 2015 Education Policy Outlook [160] noted that around 49 percent of Polish secondary students were enrolled in a vocational school. In the 2018/19 school year, more than half a million students [159] trained at nearly 1,900 post-reform technical secondary or pre-reform upper secondary schools.

Currently, at the secondary level, students who have completed grade VIII are able to enroll in one of two types of vocational institutions: either five-year technical secondary schools [145] (technikum) or three-year stage I sectoral vocational schools (branżowa szkoła I stopnia).

Technikum also prepares students with a general academic education—students enrolled in these schools study the same compulsory subjects as those enrolled in general secondary schools. However, roughly one-third of total class hours at a technikum are devoted to vocational and practical training in a specific occupation. Because students at technikum take both vocational and general academic courses they are eligible to sit for a vocational examination as well as the maturity exam at the end of the fifth year.

Three-year stage I sectoral vocational schools also educate students in many of the same general education subjects required in academic secondary schools. However, the split between general subjects and vocational subjects differs from that at technikum: at stage I sectoral schools, practical and vocational training courses take up more than 50 percent of total class hours. While this accelerated training regimen allows students to sit for vocational examinations after just three years of training, these students are not eligible to sit for the maturity exam. Students completing stage I sectoral vocational education can, however, transfer to grade II of general secondary education.

They can also continue their occupational training at a stage II sectoral vocational school (branżowa szkoła II stopnia). First rolled out in the 2020/21 school year, training at these schools lasts just two years. During this time, students take part in a four-week practical placement of at least 140 hours while also taking a limited number of general education courses. At the end of their studies, students again sit for a vocational examination. Students completing stage II sectoral vocational education are also eligible to sit for the maturity exam.

Post-secondary Vocational Study

Students who want to continue their vocational training past the secondary level can enroll in post-secondary programs at vocational schools (szkoła policealna). To be admitted, students typically need only a secondary school leaving certificate, not a maturity certificate as is required for admission to a university. The length of post-secondary vocational programs varies, typically ranging from one to two and a half years. These programs are also usually offered part-time: In 2018/19, around 85 percent [161] of students in post-secondary vocational programs were enrolled part-time.

Programs are almost entirely applied [162] in nature. Unlike vocational programs at the secondary level, post-secondary programs usually do not include general education subjects. These programs also require that students participate in a practical placement of some sort. Graduating students receive a post-secondary school leaving certificate [163]. As in secondary vocational programs, students completing a course of study at a post-secondary school are eligible to sit for vocational exams [163].

Post-secondary vocational programs are far less popular than those at the secondary level. In the 2018/19 school year, around 218,000 students [161] were enrolled in post-secondary vocational schools, less than half the number in secondary vocational schools. The majority of these post-secondary vocational students are women: That same year, women made up 70 percent of all students enrolled in post-secondary schools. The most popular fields [162] are economics and administration, information technology, medical studies, and other service sector industries.

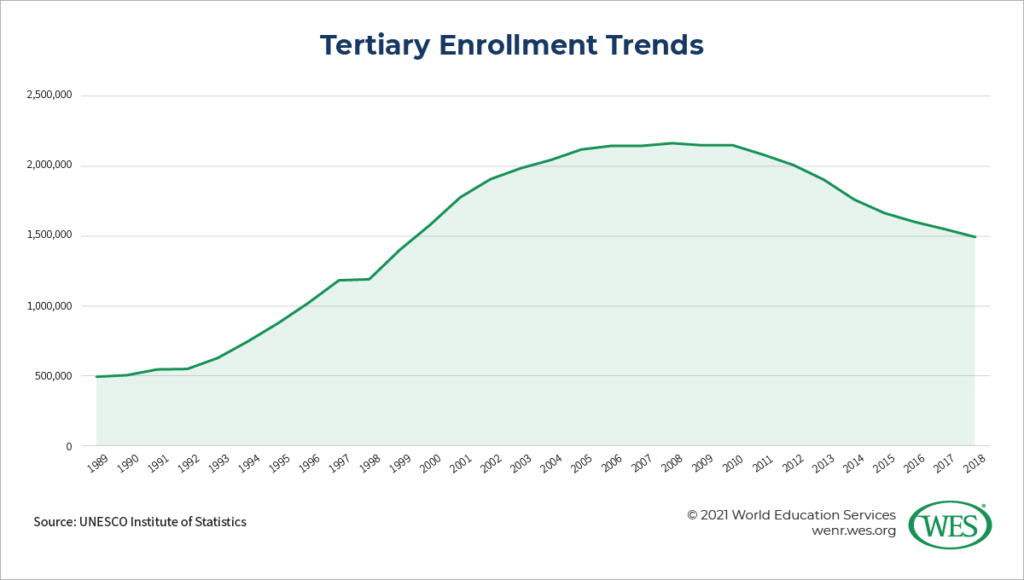

Higher Education

As in other Eastern Bloc countries, Poland’s higher education system expanded rapidly in the years after the end of communism. Between 1989 and 2008, enrollment grew by almost 340 percent, reaching 2.2 million, according to UIS data [147]. Participation also skyrocketed: The tertiary GER [164] increased from 20 to 70 percent over the same period.

However, over the past decade, demographic changes have already begun to shrink the number of Polish students enrolled in tertiary education. Despite relatively stable enrollment ratios, tertiary enrollment fell to around 1.5 million in 2018, a decline of almost a third from its peak in 2008. Demographers predict that the level of enrollment achieved in 2008 will never be reached again [166].

Higher Education Institutions

Unsurprisingly, this decline has reshaped Poland’s institutional landscape. Private institutions, which once defined Poland’s higher education system, have been hit especially hard.

Private providers ballooned in the years following communism’s collapse. During the 1990/91 academic year, just three of 112 higher education institutions [167] in Poland were private. By 2005/06, [168] their numbers had swelled to 315 (out of a total of 445 [169]). This expansion made Poland’s private higher education sector the most extensive in Europe [170].

Since then, declining demand has forced about 100 of these institutions to close or merge. By 2020/21 [171], just 219 private institutions remained. Public institutions, which are much less reliant [166] on tuition fees, fared far better. In 2020/21, the number of public institutions, 130, remained unchanged from 2005/06.

Despite their greater numbers, private institutions have long enrolled far fewer students than public institutions. In 2005/06, private institutions enrolled on average less than 2,000 students each. More than a decade later little has changed. Today, around 70 percent of all higher education students are enrolled at public colleges or universities.

These institutions, both public and private, are categorized by MEiN into two primary sub-groups: academic- or university-type (uczelnia akademicka) and professional- or non-university-type (uczelnia zawodowa).

An evaluation of the quality of research activities conducted at an institution forms the basis of this categorization. Since 2013, the Committee for the Evaluation of Scientific Units [172] (Komitet Ewaluacji Jednostek Naukowych, KEJN), recently replaced by the Research Evaluation Committee (Komisja Ewaluacji Nauki, KEN), has assessed the research output of the individual faculties, colleges, and research institutes within a college or university. Based on the results of the evaluation—which relies heavily on citation and publication metrics [173]—KEJN awards research categories or grades (A+, A, B+, B, and C) to the scientific units of individual disciplines.

MEiN classifies institutions receiving a research rating of at least B+ in one discipline as university-type. It classifies all others as non-university type.

The classification and research grade received by an institution has a significant impact [174] on its autonomy and funding. MEiN regulations allow university-type institutions to award all three levels of higher education qualifications (bachelor’s, master’s, and doctorates). University-type institutions can also award degrees for both academic and applied programs [175], which are discussed in more detail below. Regulations also reserve the terms academy (akademie), university (uniwersytety), and technical university or university of technology for university-type institutions.

Non-university institutions can only award first-, second-, and long-cycle programs, but not doctorates. They are also authorized to offer only practically oriented programs and are restricted to the use of terms like college, school, or polytechnics (uczelnie techniczne), among others, in their name or public descriptions.

Most non-university type institutions are private. In 2018/19, only nine of 230 private higher education institutions [176] were university-type. On the other hand, only around 30 percent of the 135 public institutions are non-university-type.

Despite having one of the largest higher education systems in Europe, the quality of Polish higher education lags that of its Western Europe counterparts. Universitas21, an international network of research universities, ranked Poland’s higher education system 32 of 50 in 2020 [177]. Few Polish universities rank highly on major international university rankings. Only the University of Warsaw and Jagiellonian University consistently rank among the world’s top 500.12 [178]

The Tertiary Degree Structure

Polish higher education qualifications have been reshaped significantly over the past two decades. In the early 2000s, the country began to align its qualifications with the framework adopted by the EHEA [179], requiring universities to use the European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS) and gradually introduce the three-cycle qualification framework. While the latter change eliminated most of the country’s traditional long-cycle programs, Poland, like many other EHEA member states, still retains the long-cycle structure for programs in a handful of fields.

More recently, in 2018, MNiSW regulations stipulated that all higher education programs be categorized as either academic profile (profil ogólnoakademicki) or practical profile (profil praktyczny). The difference between the two lies in the nature of the courses that make up the curriculum. For academic profile programs, more than half of the credits must be allotted to courses connected with the research conducted at the teaching institution. For practical profile programs, more than half must be earned in courses that develop practical skills, such as vocational internships. As noted above, only university-type institutions can offer academic profile programs. Non-university-type institutions are restricted to professional profile programs.

The Polish Qualifications Framework (PRK)

Another significant change was rolled out in 2016 [180]. That year, Poland finally adopted the Polish Qualifications Framework [181] (Polska Rama Kwalifikacji, PRK). Modeled after the European Qualifications Framework (EQF), the PRK comprises eight levels, to which academic, vocational, and even informal education can be assigned. Since 2017, educational institutions have been required to indicate the PRK level of the qualification on the academic documents [182] they issue.

The PRK formed the basis for the development of an even more ambitious classification project, the Integrated Qualifications System [183] (Zintegrowany System Kwalifikacji, ZSK). The ZSK aims to classify all legitimate qualifications earned in Poland, including work-based training programs, to help employers understand the training and skills obtained by employees and job seekers. Employers and others can access information about qualifications classified by the ZSK in the Integrated Qualifications Register [184] (Zintegrowany Rejestr Kwalifikacji, ZRK).

First-Cycle Programs

To enroll in a first-cycle [132] undergraduate program, a student must have completed secondary education and earned a maturity certificate. The maturity exam, introduced in 2005, replaced the internal admissions examinations which until then had been used at most higher education institutions throughout the country, although institutions sometimes still use internal admissions examinations in exceptional circumstances, such as when applicants have completed secondary education outside of Poland.

There are two primary types of first-cycle programs: licencjat and inżynier.13 [185] Licencjat programs require a minimum of 180 ECTS credits, or around three years of study, and are typically offered in the liberal arts, in disciplines such as the arts, humanities, natural sciences, and social sciences, among others.

Inżynier programs are typically longer, requiring at least 210 ECTS credits, or around three and a half years of study, and are awarded in professional disciplines, such as agricultural sciences, architecture (inżynier architekt), and engineering.

First-cycle programs can be either academic profile or professional profile. Today, programs in both profiles often include a practical component, such as an internship. They also typically require that students complete a final thesis and take and pass a final diploma examination (egzamin dyplomowy) before graduating. The final exam, taken after all other program requirements are fulfilled, assesses students’ understanding of and ability to use knowledge imparted to them throughout the entire program.

Students successfully completing all program requirements are awarded a dyplom. MEiN regulates the contents of the dyplom, which must indicate the student’s overall grade, which is determined by the student’s performance on the final thesis, on the final examination, and in all courses taken during the program.

Second- and Long-Cycle Programs

Possession of a licencjat or inżynier is typically required for admission to a second-cycle, or magister [186], program. Most magister programs require the completion of at least 90 ECTS credits, or a year and a half of study, to graduate. However, programs in some fields require more. The magister inżynier, a second-cycle engineering program, and the magister inżynier architekt, a second-cycle architecture program, typically require students to complete a minimum of 150 ECTS credits to graduate.

As noted above, alongside first- and second-cycle programs, Polish universities continue to offer long-cycle programs [187] in a handful of fields. While most long-cycle programs are offered in regulated professions, such as medicine, dentistry, and law, they are also still offered in a handful of unregulated professions, including acting, film directing, graphic design, and painting, among others.14 [188]

To be admitted to a long-cycle program, applicants must have completed their secondary education and earned a maturity certificate. Depending on the field, these programs require between 300 and 360 ECTS credits to complete, or around four and a half to six years of full-time study.

In addition to coursework, both second- and long-cycle programs typically require students to complete a final thesis and take a final diploma examination. Students successfully completing all program requirements in either cycle are awarded a magister.

A large proportion of Poles enroll in either second- or long-cycle programs. Around 70 percent [189] of tertiary-educated Poles possess a master’s degree, well above the OECD average (around 30 percent).

Professional Education

While the EHEA has encouraged its member states to adopt the three-cycle model for all higher education programs, most have been hesitant to introduce it for regulated professions [190]. Poland is no different. Currently, programs in the following regulated professions are offered almost exclusively as long-cycle programs: dentistry, law, medical analysis, medicine, pharmacy, physiotherapy, preschool and early school education, special education, and veterinary medicine.

As is the case in other EHEA countries [191], in Poland, resistance to the introduction of the three-cycle structure in medical fields has been particularly stubborn. Today, medical programs remain long cycle and usually require a minimum of six years of full-time study and training. Among the most popular are the lekarz (medical doctor), lekarz dentysta (dentist), lekarz weterynarii (veterinary physician), and magister farmacji (master of pharmacy) programs. That said, to attract international students, some Polish universities allow students completing a bachelor’s degree outside of the country to matriculate into the third year of these programs (for example, the MD Advanced program [192] at the University of Lodz).

Programs in medical fields typically require a period of clinical training, often conducted in the final two years of the program. They are also subject to oversight from the Ministry of Health [193] (Ministerstwo Zdrowia) which, among other matters, fixes the maximum admission level for domestic students to avoid overcrowding teaching institutions and overproducing medical professionals. Only university-type institutions can offer programs in medicine and health sciences.

Third-Cycle Programs

To enter a program in the third and final cycle of Poland’s higher education system, students must possess a magister, obtained in either a second- or a long-cycle program or its equivalent. These doktor, or doctoral, programs, typically require four years of study [194], although some can be completed in three.

Doctoral programs are research degrees and involve advanced coursework, practical training (such as teaching), and research in preparation for the submission and defense of a dissertation. Before graduating, doctoral students must take and pass a final exam and have at least one academic paper published by an academic publisher recognized by the MEiN.

Successful students are awarded a doctoral degree in their field of study by the doctoral board of their school or faculty. Holders of completed doctoral degrees may continue their research and work toward a post-doctoral title, called doktor habilitowany.

Although, as mentioned above, a high proportion of Poles obtain magister degrees, few go on to obtain a doctorate: Just 0.6 percent [189] of Poles between the ages of 25 and 64 possess a doctorate, compared with the OECD average of 1.1 percent.

Teacher Education

Attracting new teachers is a growing problem in Poland. Low pay has made the profession unattractive to many younger Poles, especially those living in cities where the cost of living continues to grow and higher paying jobs are readily available. As a result, enrollment in teacher education programs has declined sharply in recent years, with reports [195] indicating that teaching degrees have declined by about 60 percent over the past decade.

Teacher education and training is tightly regulated in Poland, with MEiN determining [196] the content, scope, and academic level of the training programs that qualify teachers to practice. Current regulations require that prospective teachers receive training in pedagogy, in subjects such as psychology and teaching methodology, as well as in a discipline corresponding to the subject they plan to teach. They must also complete an internship, during which they observe, assist, plan, and lead instruction in classes during on-site visits to local schools. Since 2017/18 [197], regulations have also required prospective preschool and elementary school teachers to obtain at least a first-, second-, or long-cycle degree before they begin teaching. Secondary school teachers must obtain at least a second- or long-cycle degree.

Although prospective teachers are not required to fulfill the minimum degree requirement in a teacher education program, today most still do enroll in concurrent programs [198] that allow them to specialize in both teaching and a specific subject area. Those who completed their first-cycle degree in a non-education program can enroll in shorter, non-degree programs that provide the theoretical and practical pedagogical training required to begin teaching. Both university-type institutions and those non-university-type institutions that received at least a B research grade can offer these training programs.

Prior to 2016, many prospective teachers were educated at teacher training colleges [180] (kolegium nauczycielskie), where they received a diploma of completion of a teacher training college (dyplom ukończenia kolegium nauczycielskiego) after three years of study and practice. Today, most of these colleges have been transformed into or absorbed by larger higher education institutions, where they continue to offer teacher training programs in full compliance with the latest ministerial regulations. The rest, no longer offering programs in compliance with ministry regulations, have been slowly phased out.

Some institutions also offer postgraduate degree and non-degree programs for practicing teachers. While enrollment in these postgraduate programs is not mandatory for practicing teachers, their impact on the promotion process has made them popular. Participation in continuing professional development is one of the criteria used to determine whether a teacher will be promoted to the next teaching grade.

Quality Assurance and Accreditation

Improving quality at the nation’s higher education institutions has long been a priority for Polish policymakers. In 2002, prompted to action by the proliferation of low-quality private institutions, the government established an external accreditation agency, known today as the Polish Accreditation Committee [199] (Polska Komisja Akredytacyjna, PKA). Established as an independent, autonomous agency, PKA, a member of the European Network for Quality Assurance in Higher Education [200] (ENQA), still assumes primary responsibility for evaluating higher education programs and institutions.

Changes introduced more recently have aimed at better aligning Poland’s quality assurance and accreditation processes with European standards, in particular with the principles developed in the Standards and Guidelines for Quality Assurance in the European Higher Education Area [201] (ESG). These reforms made internal quality assurance more prominent and extended and refined PKA’s responsibilities, which today include six principal evaluation procedures [202] that assess institutions as a whole as well as their individual programs.

Evaluation begins well before an institution ever opens its doors. To be entered into the Polish Register of Institutions [203] and begin teaching, all private institutions (public institutions are established by parliament) must submit a detailed application to MEiN containing information on its financial resources and strategy, among others. These applications are then reviewed and evaluated by PKA which advises MEiN on whether the institution should be entered into the registry and allowed to open. A similar institutional evaluation process is conducted at already operating institutions every six years.

Most higher education institutions must receive approval from MEiN before they can begin offering new academic programs as well. Proposed programs are evaluated by panels comprising PKA members and external experts, who examine the program’s expected learning outcomes and curriculum, as well as the institution’s learning facilities and the qualifications of their teaching staff, among other criteria. For new programs in regulated professions, such as medicine and dentistry, experts from the relevant ministries also participate.

As with institutional evaluations, MEiN issues the final permit, basing its decision on the outcome of PKA’s assessment, a report of which is published online. The duration of a program permit’s validity depends on PKA’s findings, although most programs are approved for six years—the maximum validity period—after which they must be reevaluated. Institutions establishing programs in a discipline for which they were awarded an A+, A, or B+ research category are exempt from these procedures.