Colleges and universities in the United States have been staring down a tremendous demographic challenge over the past few years: that of a declining number [2] of graduating U.S. high school students, which in turn results in fewer enrollees in higher education. This challenge has been exacerbated [3] by the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet, one group has grown over time: immigrant students. In fact, immigrants and their children made up more than one-quarter of all U.S. higher education enrollment, or about 5.3 million students, in 2018, according to a report [4] from the Migration Policy Institute (MPI) and the Presidents’ Alliance on Higher Education and Immigration. By contrast, international students, a student market of relatively greater focus for most institutions, accounted for only 5.5 percent [5] of the total student population in the 2019/20 academic year. (This dropped to 4.6 percent in 2020/21, largely because of the pandemic.) Furthermore, immigrant students represented nearly 60 percent of all student population growth from 2000 to 2018, according to MPI and the Presidents’ Alliance.

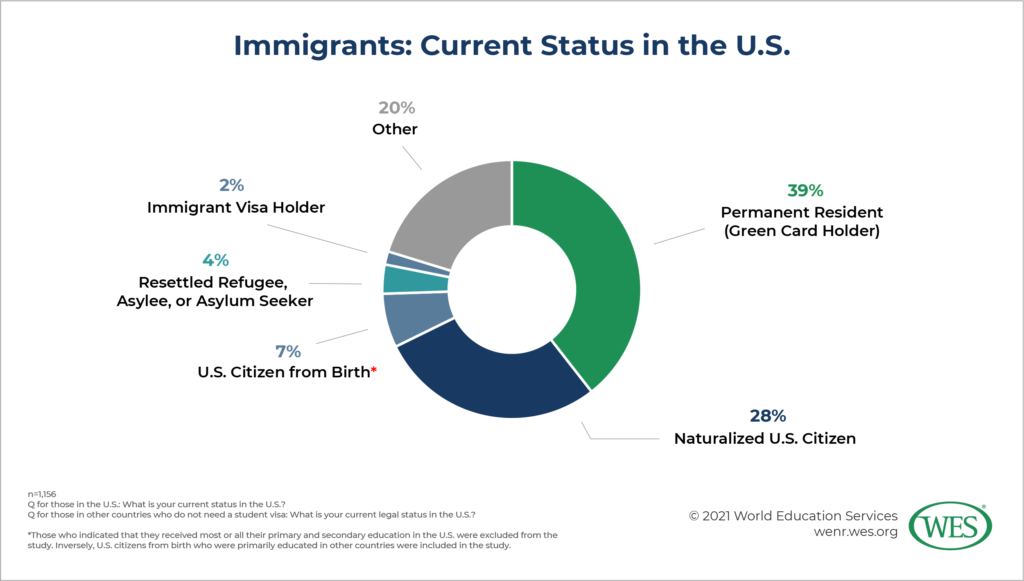

While international students, by definition, are those in the U.S. on non-immigrant student visas (F, M, or J), immigrant students are those who have moved to the U.S. from other countries and who now have either permanent or uncertain status in the U.S. (see Figure 1). Compared with international students, relatively little is known about immigrants in U.S. higher education. International students are meticulously tracked through SEVIS (the Student and Exchange Visitor Information System) [6] by federal mandate. By contrast, most immigrant students are considered domestic students for enrollment purposes, as most have permanent status in the U.S. As a result, they effectively “disappear” into the U.S. higher education system in ways that international students do not (and cannot).

[7]

[7]Click to enlarge [7]

While often overlooked as a source for recruitment, internationally educated immigrants bring unique international and multicultural perspectives to the campus community. And they are a potential demographic boon to institutions in a time when domestic enrollment is shrinking and international students face obstacles coming to the U.S. To plug the gap in research on this important group, WES conducted a survey of internationally educated immigrant students to learn more about their needs and preferences.

This article shares three of the biggest takeaways from the study. These recommendations are to:

- Provide varied and flexible course options. Many students are looking for more flexible programmatic and course offerings beyond the traditional, notably online and hybrid programs. There are also indications that many students are interested in online options that allow them to stay in their current community. That said, some students, particularly those who are traditional college-age (17 to 24) and professional degree students, are interested in full-time, in-person coursework.

- Refer students to resources that help with entrance exam preparation, where needed. The survey results made clear that such examinations are a major challenge for immigrant students, particularly those who do not speak English as their first language.

- Deal directly with issues of cost where possible. Perhaps unsurprisingly, cost is a top barrier facing immigrant students. At the same time, such students seem to respond well to easy-to-use, transparent methods of calculating or understanding the true price of a degree program, and to resources that help them apply for financial aid. As much as possible, immigrant students should be steered toward scholarships and other aid that does not need to be repaid.

The Survey

To learn more about the priorities, experiences, and needs of immigrant students applying to U.S. colleges and universities, WES conducted a survey of 1,156 internationally educated immigrants1 [8] from our credential evaluation applicant base in July and August 2021. These respondents held a wide variety of legal statuses within the U.S., including citizenship,2 [9] permanent residence, refugee status, and various immigrant visas, all of which were permanent or at times uncertain (such as those on Temporary Protected Status, or TPS [10]). The main commonality was that all respondents were internationally educated immigrants. They held educational credentials from high school or beyond from countries other than the U.S. Consequently, this study does not include those who came as children (regardless of status) and received most or all of their K-12 education in the U.S. (This would include most recipients of DACA, or Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals [11].) All respondents were either applying to, enrolled in, graduated from, or withdrew from a U.S. college or university. They all had experience with the application process, the primary focus of this survey. Fifty-eight percent were pursuing a master’s degree, with the rest distributed among all other levels of higher education.

Recommendation 1: Provide Varied and Flexible Course Options

One of the clearest outcomes of the survey is that many students are looking for varied coursework options to accommodate their needs. At the same time, some students, notably many younger students and those working toward professional degrees (such as medicine), want traditional, full-time, in-person coursework. Here are some key recommendations based on the findings:

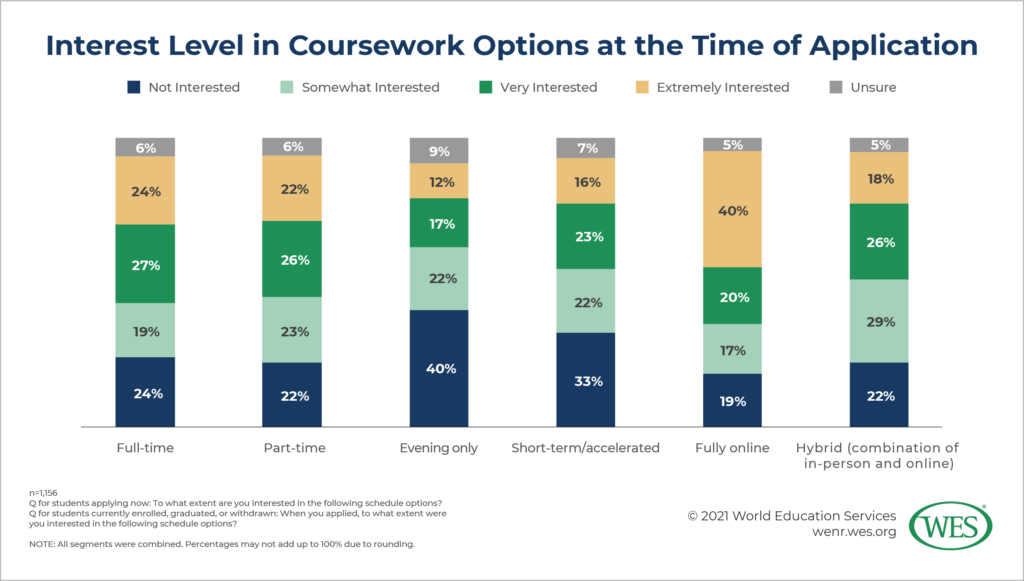

Expand flexible and cost-effective options, particularly online and part-time offerings. When asked about their level of interest in different types of coursework options (see Figure 2), respondents were by far most interested in fully online coursework. Forty percent said they were “extremely interested” in this option, compared with 24 percent holding the same level of interest in full-time, in-person coursework. Part-time coursework was also relatively popular, with 22 percent saying they were extremely interested.

[12]

[12]Click to enlarge [12]

Other options were less popular. A full 40 percent of respondents were “not interested” in evening coursework, and one-third of respondents were similarly not interested in short-term, accelerated programs. Hybrid programs–which offer coursework that is split to varying degrees between online and in-person–lie somewhere in the middle.

Alternative options to traditional coursework (full-time and in-person) are particularly popular with “non-traditional students,” typically (and perhaps simplistically) defined [13] as those older than 24 years old. The survey data reveal a correlation between age and interest in certain types of coursework options, almost certainly related to having greater work and family responsibilities. As individuals become older, the likelihood that they would be highly interested in traditional, full-time coursework decreases. Over half of 17- to 24-year-old students are “extremely interested” in full-time coursework, compared with 28 percent of 25- to 34-year-olds. This rate drops progressively by age group, with only 14 percent of 45- to 54-year-olds expressing high interest in traditional coursework and opting for part-time or fully online coursework instead.

Those who are employed full-time are more interested in alternative options. They are most interested in part-time and fully online coursework, particularly compared with those who are employed part-time or not at all.

Target online options to those not in the local area. When asked about priorities regarding the location of a prospective institution, over one-quarter of immigrant respondents said they needed to stay where they currently live. This was the second-highest priority concerning location, selected after “job opportunities in the local area.” Many immigrants put down roots in their local U.S. community that center on work and relationships; relocating for college or university is difficult or not feasible for many. Additionally, women in the survey seem to find attending an institution away from home somewhat more difficult than men do. Fifteen percent of female respondents found this “extremely challenging,” compared with 10 percent of male respondents. By contrast, 19 percent of men said it was “not challenging at all,” compared with 11 percent of women. (Perhaps surprisingly, there were no significant differences between men and women on the extent to which family responsibilities are a challenge when it comes to attending school.)

Online options can open up more possibilities to these less-mobile students by providing more choices in programs and course offerings than what is available in the students’ local area. At the same time, increased online offerings allow an institution to access a wider base of students–potentially located across the U.S. and even around the world.

Understand where some types of degrees and programs may need to be in person. Despite the increased interest in online and hybrid learning, not all programs lend themselves well to a digital platform. One notable finding is that students in professional degree programs, such as medicine and law, notably favor those that are full-time and in person. Thirty-seven percent of these students were extremely interested in full-time coursework, compared with 26 percent of bachelor’s students and 22 percent of master’s students.

Recommendation 2: Refer Students to Resources That Help with Entrance Exam Preparation, Where Needed

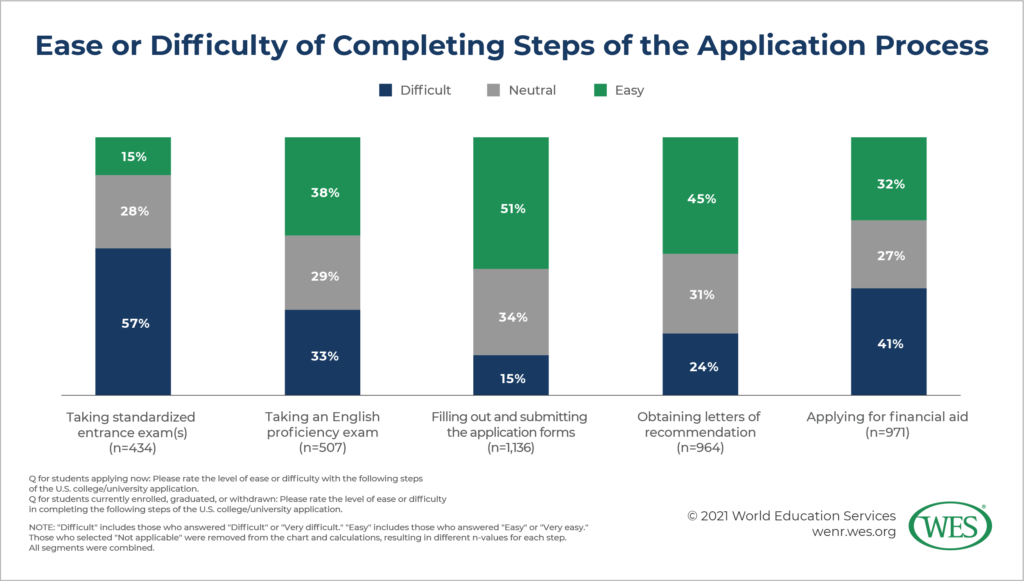

A clear barrier that immigrant students face in the admissions process is standardized entrance exams, such as the SAT and GRE. Interestingly, more respondents than not said that such exams were “not applicable” to them. This can likely be explained by a number of factors—many institutions are now test-optional; other institutions and programs are more open access. However, among those who did take standardized exams, over half (57 percent) said they were “difficult” or “very difficult.” It was the most challenging component of the admissions process for this group, out of all aspects they were asked about (see Figure 3). Our study also revealed that, not surprisingly, those who do not speak English as their first language struggle in particular with such exams.

[14]

[14]Click to enlarge [14]

Perhaps surprisingly, English proficiency exams such as the TOEFL and IELTS were less of a challenge. One-third found them difficult, while 38 percent said they were easy and 29 percent “neutral.” In general, English is not a major barrier to immigrant students, though about 43 percent of respondents self-identified as native speakers of English.

While some institutions are now test-optional or have never required such exams (for at least some programs or degree levels), many institutions will continue to rely on these tests as an important way to assess student aptitude. For institutions and programs that do require standardized tests, here is one possible practice that can help immigrant students: test preparation.

Where entrance exams will continue to be required, many immigrant students will need some assistance preparing for them. Sixty-one percent of respondents who made use of exam preparation courses and services found them “very helpful” or “somewhat helpful.” (Most respondents, however, did not use these services.) Local immigrant- or refugee-serving organizations may be good partners in helping immigrant students access and pay for these courses.

Recommendation 3: Deal Directly with Issues of Cost Where Possible

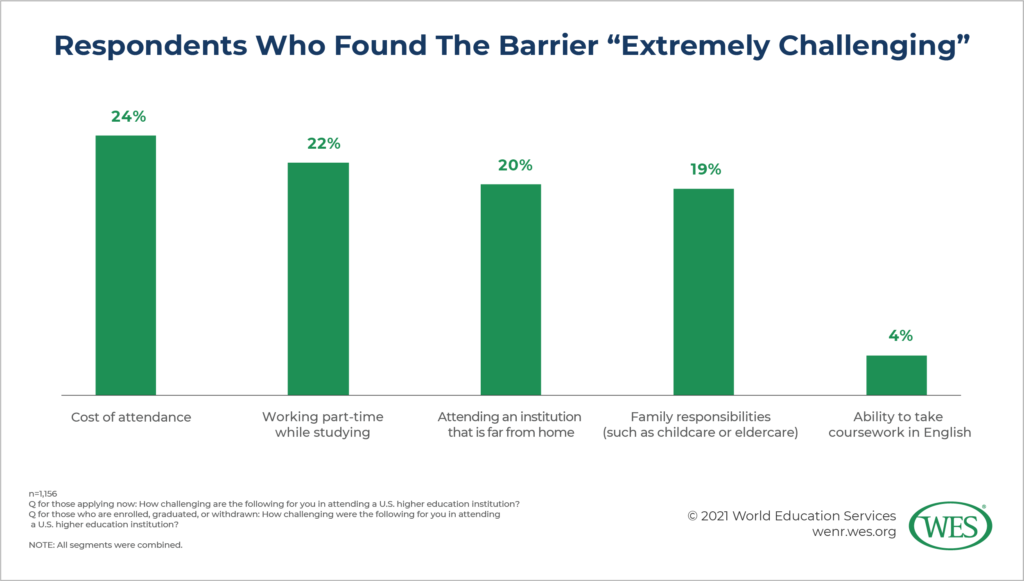

The top barriers overall facing immigrant students are cost and concerns about access to financial aid. Among the features of an institution that immigrant students look for, cost is the second-biggest factor after overall quality of education. This includes tuition and fees, as well as securing any financial aid. When respondents were asked to directly compare cost with several other factors, cost was selected as the most important factor nearly 40 percent of the time, and it was selected as least important only about 8 percent of the time (see Figure 4).

[15]

[15]Click to enlarge [15]

Additionally, when asked about potential barriers to attending, about one-quarter each found cost “extremely challenging,” “very challenging,” or “moderately challenging.” Here are some recommendations:

Provide transparent, easy-to-use cost calculating tools. Among the most helpful resources were those that helped with determining the total cost of obtaining a degree. Forty-six percent rated such tools–which could include information on the internet and professional advising–“very helpful.” U.S. colleges and universities generally have a cost calculator [16] on their website, but such tools’ ease of use to immigrant students may vary tremendously. Institutions that are serious about helping immigrant students may want to think about how to make such tools as easy to use as possible for someone new to the U.S., not very knowledgeable about U.S. higher education, and whose first language is not English.

Provide resources for finding and applying for scholarships and grants, and allocate scholarship funds for immigrant students, where possible. Another set of tools that were useful to many students were those that helped with finding and applying for scholarships and other forms of financial aid. Forty-five percent of students who used such resources found them “very useful,” while another 26 percent said they were “somewhat useful.” To the greatest extent possible, it is important for immigrant students to apply for scholarships, grants, and assistantships ahead of loans, given the particular financial challenges [17] that immigrants often face.

Final Thoughts

Immigrant students are a diverse and nuanced group that can never be fully explored in one study. But one thing is clear: Organizing and allocating resources along a domestic/international student dichotomy can overlook the needs of this increasingly important group within U.S. higher education. Astute institutions will invest in these students and in the services and opportunities that will allow immigrant students to maximize their potential.

1. [18] Valid responses only

2. [19] Some respondents were U.S. citizens from birth but had completed most of their K-12 education in countries other than the U.S. We consider them “cultural immigrants,” even if not immigrants in a legal sense.