Editor’s note: This article is an updated version of an article originally published [2] in October 2016.

Diplomas issued by international schools in China are a common sight for international credential evaluators and admissions officers in North America. As in many Asian and Middle Eastern countries, demand for Western education and English-taught school programs has been surging in China in recent years. The country is now said to have the highest number of English-medium international schools worldwide next to the United Arab Emirates [3]. Whereas international schools in China once catered primarily to expat children, growing numbers of youths from China’s middle-class households can now afford to enroll in these often-expensive schools, which in extreme cases charge tuition fees of up to US$40,000 per year.

This trend is reflected by the rapid expansion of officially recognized international schools in China, which almost tripled over the course of the past decade, from 384 in 2010 [4] to 932 in 2021 [5], according to the Chinese market research company New School Insight. The international school market is also no longer confined to first-tier cities like Beijing, Shanghai, or Shenzhen but has grown strongly in second- and third-tier cities as well.

At the same time, there are doubts about whether this rapid expansion will continue amid tighter regulations imposed on international schools by the Chinese government. Growth rates in the sector have already slowed, tapering off markedly between 2020 and 2021 [5], and in recent months [7], several international schools have closed. New legislation1 [8] enacted in 2021 makes it mandatory for private international schools that enroll Chinese students to align their curricula more closely with the standards of the state curriculum and prohibits the use of foreign textbooks in elementary and lower-secondary schools—measures that could hamper further international school development, observers say [9]. Chinese education policies in recent years have illustrated Beijing’s desire to weaken the influence of Western education and thought, even at the country’s international schools. The coronavirus pandemic and the resulting disruptions to international student mobility also harmed the sector and forced several schools to close their doors [10] due to a lack of students [11].

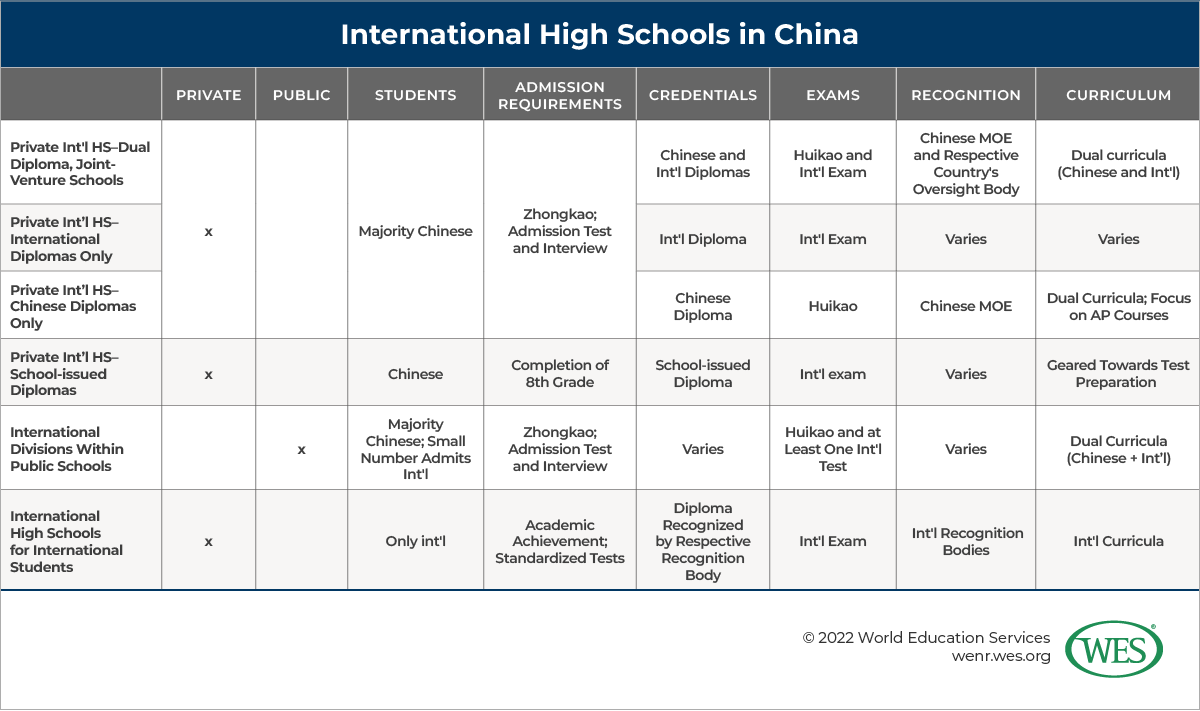

These developments notwithstanding, admissions offices at universities in the United States and Canada will continue to receive sizable numbers of applications from students who earned an international school credential in China, at least for the foreseeable future. When assessing these qualifications, it’s important to understand that China’s international school sector is far from homogeneous. There are several types of international schools, including schools that are only permitted to enroll expat children, joint Sino-foreign cooperative schools, or private Chinese high schools offering dual curricula. These schools may be run by a variety of providers, including well-known foreign education providers and private Chinese companies, or they may be attached to public Chinese schools.

There are significant qualitative differences as well. While most of the recognized international schools in China offer established international curricula taught in English, such as the British International General Certificate of Secondary Education (IGCSE), U.S. Advanced Placement (AP) courses, or the International Baccalaureate (IB), there are also hundreds of prep schools outside of the formal education system designed to prepare Chinese students for international university education that are neither recognized in China nor internationally. It’s critical that international enrollment and recruitment personnel are aware of these distinctions as they are directly relevant to Chinese international students’ preparedness, experience, and success on U.S. and Canadian campuses. This article provides an overview of the different types of schools and programs in China, as well as the credentials they award.

Types of International High Schools in China

International schools in China can be categorized into four types:

- Schools for the children of foreign workers, as they are officially called

- Sino-foreign cooperative schools

- International divisions within public Chinese high schools

- Private Chinese international schools

Schools for the Children of Foreign Workers

These expatriate schools were first established in the 1990s and are designed to provide education to the children of foreign nationals working in China. Except for students from Hong Kong and Macau, Chinese students are not allowed to enroll in these schools unless at least one of their parents holds a foreign passport.

Frequently located in top-tier cities and provincial capitals, expatriate schools are generally private and foreign-owned, although Chinese companies may also run these schools. They teach international curricula and conclude with the award of internationally recognized high school qualifications. These schools are recognized by international accreditation bodies, such as the U.S.-based Western Association of Schools and Colleges (WASC), the International Baccalaureate (IB), or Cambridge Assessment International Education. They have admission requirements comparable to schools in the U.S. and Canada and most of their faculty are licensed international teachers. One example is the Shanghai American School [12], which is both fully accredited by WASC and is an IB World School. Students can choose to take U.S. high school and AP courses or study the IB curriculum and graduate with a U.S. high school diploma or the IB Diploma.

Expatriate schools were once the only type of international school permitted in China; their number grew strongly as China experienced a rapid inflow of foreign workers in the early 2000s. However, enrollments at expat schools have since stagnated [13] and these schools made up only 15 percent of all international high schools in China in 2019, according to the market research firm Daxue Consulting [14]. A list [15] of expatriate schools is provided by the Chinese Ministry of Education (MOE).

Sino-Foreign Cooperative Schools

Sino-foreign cooperative schools are joint ventures between foreign education providers and Chinese institutions. The latter are often privately owned and responsible for supplying the local infrastructure and facilities. Sino-foreign cooperative education exists at both the upper- and post-secondary levels but is not permitted at the elementary and lower-secondary levels (basic education). While these schools can enroll both Chinese and expat students, they are mainly geared towards local students. These joint ventures allow China to modernize and increase capacity in its education system while maintaining greater control over the educational content than is the case at independent expatriate schools.

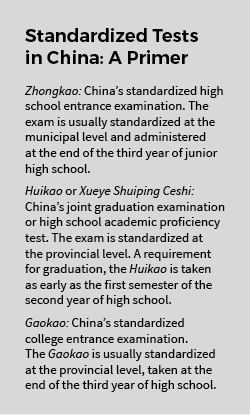

[16]Sino-foreign cooperative schools need to be approved and recognized by both the Chinese MOE and the relevant oversight body in another country, such as the U.K., the U.S., Australia, or Canada. Unlike expatriate schools, admission to upper-secondary joint venture schools is generally contingent on performance on China’s standard high school entrance examination (Zhongkao).

[16]Sino-foreign cooperative schools need to be approved and recognized by both the Chinese MOE and the relevant oversight body in another country, such as the U.K., the U.S., Australia, or Canada. Unlike expatriate schools, admission to upper-secondary joint venture schools is generally contingent on performance on China’s standard high school entrance examination (Zhongkao).

Once enrolled, students pursue dual academic tracks and curricula—Chinese and international. To graduate, students must sit for two sets of exit exams, the Chinese Huikao and the international exam for which they’ve prepared, such as the GCE A-levels. Students at these schools earn both Chinese and foreign credentials.

The Beijing Royal School [17] is an example of this type of school. It offers bilingual curricula and dual diploma tracks. Its students sit for the Huikao as a graduation requirement, and, upon successful completion, obtain a high school diploma recognized by the Beijing Municipal Department of Education. Depending on their chosen curriculum, they also obtain either a high school diploma from a U.S.-accredited high school—which is awarded upon completion of the required AP courses—or an IB Diploma.

International Divisions Within Public Chinese High Schools

A number of public Chinese schools have established divisions that offer an international curriculum in addition to the regular Chinese one. Only a part of the student body at these public schools enrolls in an international program, which usually charges much higher tuition fees—a fact that has sparked criticism and concerns regarding equity and access in China [18], given that the schools are government-funded and use public resources. Some provinces have consequently placed restrictions on public international school divisions, but they still accounted for about one third of international schools in China in 2019, according to Daxue Consulting [14]. Many of these programs are set up in collaboration with private companies, domestic or foreign, and may operate independent of the public schools to which they are attached [18].

The international programs are mainly geared towards domestic students seeking to subsequently apply to universities abroad, although some schools may admit expatriate students as well. Like students in regular high school programs, students at international division schools are admitted based on their Zhongkao results. They then follow a bilingual, bi-curricular course of study. However, while many programs allow students to earn dual qualifications, other programs offer more limited curricula that include some international courses in addition to the Chinese curriculum but don’t conclude with a formal international high school qualification.

In one scenario, students graduate with dual diplomas—a Chinese government-issued high school diploma and an international one. For example, Chengdu Shude High School [19] is a tier-one public school in Chengdu, Sichuan Province. Its international division is sanctioned by the Chengdu municipal department of education. If qualified, students who graduate can obtain not only a Chinese diploma, but also an Australian Certificate of Education recognized by the Australian state of Victoria.

In another scenario, students graduate with a Chinese diploma and some internationally recognized education credits. For instance, the International Department of the Affiliated High School of South China Normal University [20], offers an extensive AP curriculum. Highly regarded in China and internationally, the school nonetheless only awards graduates a Chinese diploma issued by the municipal district. Students do graduate with AP credits, but not a U.S. diploma.

In rare instances, students enrolled in dual diploma programs at public schools may only obtain an international qualification, but not an official government-issued Chinese diploma. The reason for this is that students must sit for the Huikao exam in the province in which they are officially registered. For example, the International Department of the Affiliated High School of South China Normal University [21] admits many non-local students (known as Zexiao Sheng), who cannot sit for the Huikao unless they go back to their home towns, where the records required to sit for the exam are stored. Many can’t spare the time or money needed to return to their hometowns, so they do not take the exam. These students then only obtain an unofficial school-issued Chinese diploma in addition to the international credential.

Private Chinese International Schools

Privately run Chinese schools accounted for more than half of all international schools in China in 2019. These schools traditionally had greater leeway in structuring their programs than Sino-foreign cooperative schools or public international school divisions. Unlike the latter, independent private schools can, for instance, offer junior-secondary programs as long as they follow government guidelines. Schools in this category may also set their own admission requirements. While the most reputable schools require that students take the Zhongkao to be admitted into high school programs, or may conduct additional admissions interviews and tests, other schools accept students who finished junior high school (grade nine) regardless of nationality.

The quality of education provided by private international schools varies. The majority are expensive, high-quality institutions with top-notch facilities that offer English-taught or bilingual curricula that are internationally recognized (i.e., IB, AP, IGCSE, etc.). Many are designed to serve as a springboard for overseas university education—in some cases, they exclusively award international qualifications without offering students the option to sit for the Huikao exam and earn an official ministry-issued Chinese diploma. Others employ dual curricula which include internationally recognized university-preparatory courses, but only grant Chinese diplomas.

On the other end of the spectrum are providers of lesser quality with poorly trained teaching staff. These schools often promise to prepare students for university admission in the U.S. and elsewhere, but actually graduate students without adequate English skills or recognized international course credits or diplomas. Some schools may advertise AP courses without having proper accreditation or engage in other questionable practices. In one prominent instance, the Canadian International Academy (CIA) of Shanghai [23], an Ontario-registered institution in China, was not only accused of employing uncertified teaching staff, but of allowing students to pay to retake tests and alter their transcripts to reflect better grades.

Informal International Prep Schools

The increase in the number of international high schools in China isn’t the only manifestation of the growing demand for international education by China’s middle-class families. There has simultaneously been a proliferation of internationally oriented informal prep schools. Most of these schools are for-profit businesses run by education consulting firms or agents (sometimes in collaboration with other schools, sometimes not) and are geared solely towards test preparation and helping students obtain admission to international schools or foreign universities. There are literally hundreds of these schools now in existence.

The Chinese government in 2021 took steps to rein in private tutoring companies by barring foreign investment in these schools, suspending the issuing of new licenses, and prohibiting schools from tutoring in certain subjects [24]. Some provinces ordered companies to stop tutoring children from kindergarten to 9th grade altogether [25]. It remains to be seen how these measures will affect international prep schools, but it seems clear that the Chinese government is taking an increasingly hardline stance regarding private education in the school system.

As of now, however, schools in this sector operate largely in a gray zone in terms of quality. As they set no admission requirements beyond a family’s willingness to pay, the students they admit possess a range of qualifications: Some enter as early as 8th grade; some are high school graduates seeking additional test prep; and some have dropped out of high school and are seeking to reenter the educational mainstream. Students at these schools only earn school-issued diplomas or certificates of completion. These certificates aren’t officially recognized in China or abroad.

World Education Services (WES) advises against relying on these types of certificates to make admissions decisions. International credential evaluators and admissions officers should also review all submitted credentials carefully, as we have seen examples of certificates made to look like high school diplomas, in some cases issued by schools affiliated with unaccredited schools in the U.S.

1. [26] “Private Education Promotion Law of the People’s Republic of China”. See: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2021-05/14/content_5606463.htm [27]