“Ultimately, knowledge is a deep-seated treasure and education helps in its manifestation as the perfection which is already within an individual.”

— The National Education Policy of India 2020

India today is a vastly different country from the India of just a few decades ago. Strong economic growth, a ballooning youth population, and an improving education system, particularly at the tertiary level, have propelled the country onto the world stage. At the same time, India has increased its investment in and adoption of web-based technologies, making accurate and up-to-date information more easily accessible across government agencies and others which long operated using paper records that were difficult to obtain.

World Education Services (WES) is a non-profit social enterprise dedicated to helping international students, immigrants, and refugees achieve their educational and career goals in the United States and Canada. The organization has a 48-year track record of objectively evaluating academic credentials from around the world to determine their U.S. and Canadian equivalencies. This work demands that we stay abreast of the latest developments in global education so that our evaluations are accurate for each of the 200-plus countries and territories where our applicants have studied.

In the case of India, enhanced transparency, improved quality assurance mechanisms, and the ongoing implementation of ambitious reforms have prompted us to reappraise our assessment of some of the nation’s two-year master’s degrees. Following a thorough review of recent developments, WES now evaluates select master’s degrees awarded by accredited Indian universities as equivalent to master’s degrees conferred in the U.S. or Canada.

This ensures that WES evaluations continue to reflect the true academic value of the education obtained by Indian master’s degree students.

This article, which accompanies the rollout of the new WES policy, outlines the developments that helped inform our decision. It also explores the new policy’s potential impact. With nearly half a century of experience in the field of international academic credential evaluation, WES is well-placed to understand the effect that improvements in educational quality and their reflection in credential evaluation policies can have on individuals, institutions, and communities around the world.

Changes to India’s Higher Education System

The size, diversity, and dynamism of India’s higher education system pose unique challenges to credential evaluators. During the 2019/20 academic year, an estimated 38.5 million students [2]—more than in all the countries of Europe combined—studied at the country’s more than 55,000 higher education institutions.

Dotting India’s cities and towns, these institutions vary in size and status, ranging from small, specialized colleges attended by fewer than 100 students, to massive, general universities enrolling hundreds of thousands. Owned and operated by public entities, private businesses, and others, these institutions offer a dizzying array of undergraduate and postgraduate qualifications, taught in a rich variety of local and global languages. Overseeing them all is an intricate and, at times, overlapping patchwork of central and state agencies and professional regulatory bodies.

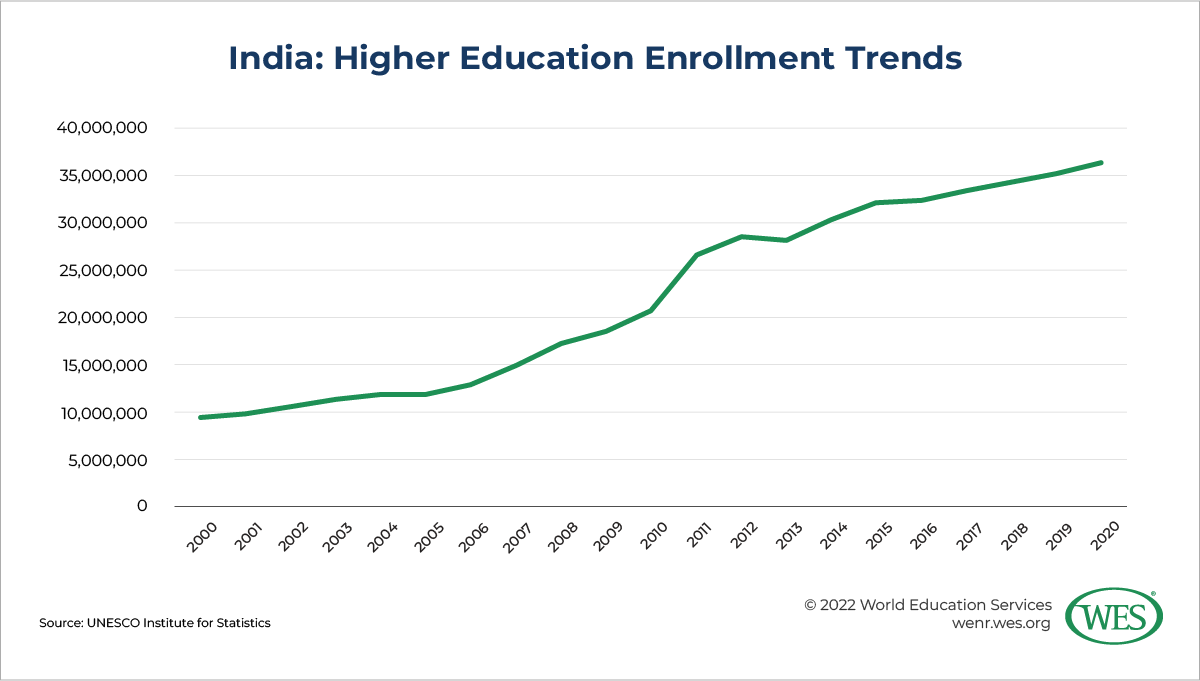

Rapid growth has made obtaining an accurate picture of India’s higher education system even more challenging. Since the start of the twenty-first century, India’s higher education system has expanded at a blistering pace. Over that time [3], the number of higher education institutions and students more than quadrupled, opening the door to a university education for tens of millions of Indian students.

But to those on the outside looking in, this rapid expansion of enrollment and proliferation of institutions raised concerns [5] about quality and the government’s ability to effectively regulate the higher education sector. Reports from inside the country of overcrowded lecture halls, predatory institutions, and other quality issues were common. At the same time, a scarcity of accurate, up-to-date information on the country’s colleges and universities made it difficult to assess the prevalence of these problems.

As a result of these conditions, many evaluation bodies around the globe have been reluctant to move beyond the cautious, conservative approach they have long taken with Indian credentials. Many universities and employers in the U.S. and Canada remain reluctant to evaluate some Indian credentials as equivalent to those earned elsewhere.

In recent years, however, India’s central and state governments have introduced reforms aimed at mitigating the negative effects of the rapid expansion of enrollment on the quality of the country’s higher education system. Government officials have launched programs designed to stimulate and measure [6] innovation [7] and excellence [8] at the nation’s colleges and universities. And they have backed these projects up with increased funding. Between 2014/15 and 2020/21, government spending on education [9] nearly doubled.

In 2017, the central government even established a specialized agency [10] dedicated to higher education financing. That same year, the National Assessment and Accreditation Council (NAAC), which assumes primary responsibility for accrediting India’s colleges and universities, announced far-reaching revisions [11] to its accreditation policies and procedures. Reflecting global best practices, such as the adoption of less-subjective assessment criteria and the incorporation of student feedback, the revised policies significantly strengthen the country’s quality assurance and accreditation mechanisms.

[12]Government agencies have also adopted policies aimed at expanding participation in the accreditation process. The University Grants Commission (UGC), which oversees the nation’s higher education system, issued a regulation [13] in 2012 requiring all colleges and universities to obtain accreditation from a recognized agency, such as NAAC, or risk losing access to federal grants or having their UGC approval revoked. Similarly, the All India Council of Technical Education (AICTE), which regulates technical education across the country, announced [14] that it will only approve institutions that have obtained accreditation from the National Board of Accreditation (NBA) for at least half of their technical programs. Although implementation has been sluggish, these measures have encouraged growing numbers of colleges and universities to seek accreditation from recognized agencies.

[12]Government agencies have also adopted policies aimed at expanding participation in the accreditation process. The University Grants Commission (UGC), which oversees the nation’s higher education system, issued a regulation [13] in 2012 requiring all colleges and universities to obtain accreditation from a recognized agency, such as NAAC, or risk losing access to federal grants or having their UGC approval revoked. Similarly, the All India Council of Technical Education (AICTE), which regulates technical education across the country, announced [14] that it will only approve institutions that have obtained accreditation from the National Board of Accreditation (NBA) for at least half of their technical programs. Although implementation has been sluggish, these measures have encouraged growing numbers of colleges and universities to seek accreditation from recognized agencies.

While government officials were rolling out these reforms, India’s technology revolution transformed how knowledge and information were shared, both within the country and beyond. Although internet access in India once trailed that of comparable countries [15] by a significant margin, over the past decade the percentage of the nation’s population using the internet has skyrocketed, growing from 7.5 percent [16] in 2010 to 41 percent in 2019. At the same time, government agencies, educational institutions, and private enterprises have increased their investment in and adoption of web-based technologies.

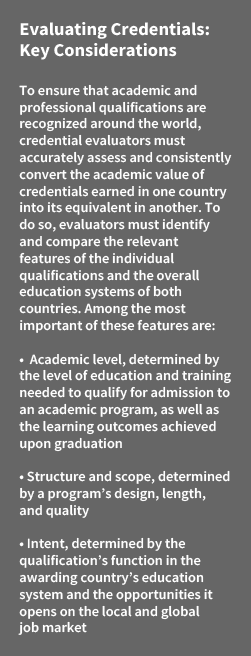

These investments have made India a leader [17] in the world’s digital transformation. They have also made accurate and up-to-date information on the state of India’s higher education system more accessible than ever before. The rapid adoption of digital technologies by India’s colleges and universities has granted credential evaluators an unprecedented degree of insight into the academic level, structure and scope, and intent of Indian qualifications. The government’s lofty reform plans for the coming decades are expected to expand that understanding even further.

In mid-2020, India launched the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 [18], a comprehensive framework designed to guide the nation’s education strategy until 2040. The goals of the NEP 2020 are ambitious. Over the next two decades, the policy aims to transform India into “an equitable and vibrant knowledge society, by providing high-quality education to all, and thereby making India a global knowledge superpower.” To do so, the policy announces, the government plans to rapidly boost funding for the country’s education system; it also reaffirms the nation’s long-standing, and long unmet, commitment to spending at least 6 percent of its gross domestic product on education.

The plan envisions an extraordinary expansion and transformation of India’s education system. It commits the government to ensuring that all girls and boys are enrolled in preschool, elementary, or secondary education by 2030, and that half of all university-age youth participate in academic or vocational higher education by 2035. With only about a quarter of that age group enrolled in a higher education program in 2018, the latter goal is particularly ambitious. If the government can achieve that goal, even partially, it will fundamentally transform not just India’s higher education system, but the nation itself. Given India’s size, the positive impact of this expansion will be felt both regionally and around the world.

The NEP 2020 outlines significant changes to the structure of the nation’s higher education system. The policy places special emphasis on four-year bachelor’s degree programs, signaling a shift away from the three-year undergraduate programs long prevalent at Indian universities. It notes that this realignment will better prepare students with the multidisciplinary education and critical thinking skills needed in the modern world.

The policy announces the eventual discontinuation of the Master of Philosophy degree, a program accessed after the completion of a standard two-year master’s degree and, at times, required for admission to a doctoral program. Because of its unique place in India’s higher education system, credential evaluators have frequently regarded the Master of Philosophy degree as equivalent to a U.S. or Canadian master’s degree, while considering the two-year master’s degree that precedes it as comparable to a U.S. or Canadian bachelor’s degree. Eliminating the Master of Philosophy degree will mean that India’s standard two-year master’s degree provides direct access to the PhD, a change that better aligns the academic level and the intent of the latter degree with master’s degrees earned in the U.S. and Canada.

The NEP 2020 outlines plans to reshape the higher education system’s institutional and regulatory landscape. A new umbrella institution, the Higher Education Commission of India (HECI), will centralize oversight and administration of higher education institutions and replace the UGC. Under it four independent councils will be established, including the National Higher Education Regulatory Council (NHERC), which will regulate institutions’ financial probity and governance processes through full public disclosure, and the National Accreditation Council (NAC),1 [19] which will supervise a network of independent accrediting agencies. These restructured regulatory institutions will increase the nation’s assessment and accreditation capacity, giving India’s educational authorities the tools they need to simplify the country’s complex network of higher education institutions.

The NEP 2020 describes a plan to consolidate the many categories into which India’s higher education institutions are currently divided into one of just two groups: a university or an autonomous undergraduate degree-granting college. This shift requires that all of India’s roughly 40,000 affiliated colleges obtain accreditation from a NAC-recognized body by 2035, after which they will be absorbed into one of these new types of institutions, creating a more manageable nationwide network of large, multidisciplinary institutions. The NEP 2020 notes that the size and breadth of these new institutions will allow for the cross-disciplinary collaboration and large-scale resource efficiency that characterize the world’s most prominent and well-regarded universities.

WES’ assessment guidelines ensure that our equivalencies reflect recent improvements made to India’s higher education system. As the NEP 2020 implementation proceeds, we will continue to monitor the need for additional refinements.

Potential Impact of the WES Policy Change

Our experience suggests that the impact of the new WES policy could be sizable. In 2006, WES revised its policy for evaluating selected three-year bachelor’s degrees from India. The new policy recognized that the level of learning attained in these programs by high-performing students at high-quality institutions was comparable to that achieved by these students’ peers in the U.S. and Canada.

Prior to this change, most credential evaluators did not equate India’s three-year bachelor’s degree to a bachelor’s degree earned in the U.S. or Canada. As a result, most Indian bachelor’s degree holders were not eligible for direct admission to graduate schools or to jobs requiring a bachelor’s degree in these two countries.

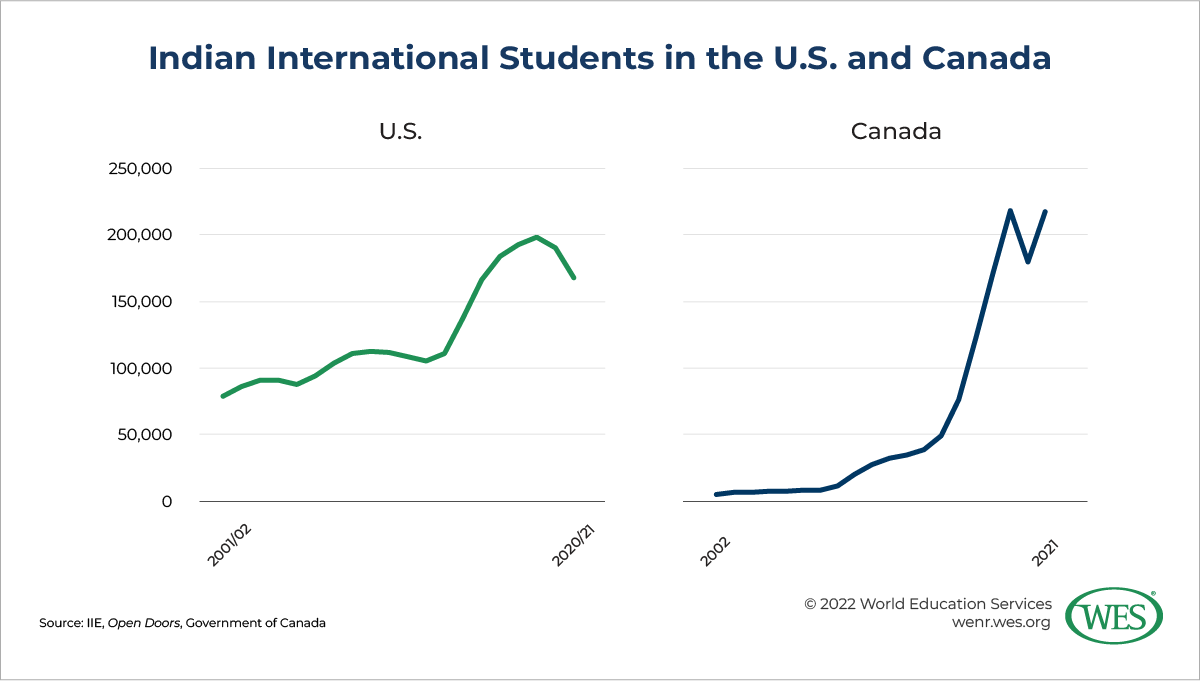

Our 2006 policy change has benefited thousands of Indian students. Adopted in the middle of a dramatic upswing in Indian international mobility, the new policy helped numerous Indian bachelor’s degree holders enroll in colleges and universities across the U.S. and Canada. The new guidelines helped even greater numbers to leverage their education and training in pursuit of professional careers and life opportunities in these two countries.

Once here, these students have excelled, both during and after their studies. Indian students now occupy a disproportionately high share of seats in some of the most prestigious graduate programs in the U.S. and Canada. After graduation, many have gone on to work in rapidly growing but labor-starved industries in both countries. Some have forged paths that are even more notable. Indian nationals—many of whom began as international students—have established [21] some of the most innovative and successful businesses here, or attained leadership positions in them.

Their contributions have not only enriched their host countries but have also uplifted their home. The many Indian international students who return home after graduating bring with them new knowledge and skills, helping to power India’s rapid development. Those who stay contribute as well. Remittances from Indian nationals working overseas are a major source of foreign exchange in India today.

The situation that prompted us to revise our policy in 2006 is similar to what’s happening today. Improvements made to the quality assurance mechanisms governing India’s higher education institutions, which began with the creation of NAAC in 1994, gave us the confidence to make changes that opened the door to educational opportunity for many thousands of students.

It’s our hope that our latest policy revision will have a similar effect. We believe that updating our equivalencies to reflect the profound changes taking place in India will allow thousands of the country’s master’s degree students to demonstrate the value of their degrees to potential employers and admissions officers in the U.S. and Canada.

The impact of our updated policy will undoubtedly grow with time. In the next few years, India’s massive youth population—more than 600 million [22] Indians, or around 45 percent of the nation’s population, under the age of 24 today—will surpass China’s to become the world’s largest. And, in the coming decades, the number of Indians pursuing a master’s degree is also likely to swell. While many of the country’s youth already pursue a master’s degree—4.3 million in 2019/20 alone—the steady growth of India’s middle class will most likely allow more and more young people to afford an undergraduate and postgraduate education with each passing year. These trends will help the country meet the NEP 2020’s ambitious goal of enrolling half of all university-age Indians in a higher education program by 2035.

As India’s higher education system expands and evolves, WES’ policy will provide the country’s master’s degree students and graduates with a valuable tool they can use to demonstrate the true value of their education and training. This change will open exciting new pathways to success, allowing countless numbers of Indian students and immigrants to fully utilize their talents and education to achieve their academic and professional goals in the U.S. and Canada.

1. [23] Not to be confused with the National Assessment and Accreditation Council (NAAC).