This article is Part I of a multi-part investigation of the shifts impacting Chinese international student mobility to the U.S. Read Part II [2] here.

Part I: Politics and the Pandemic

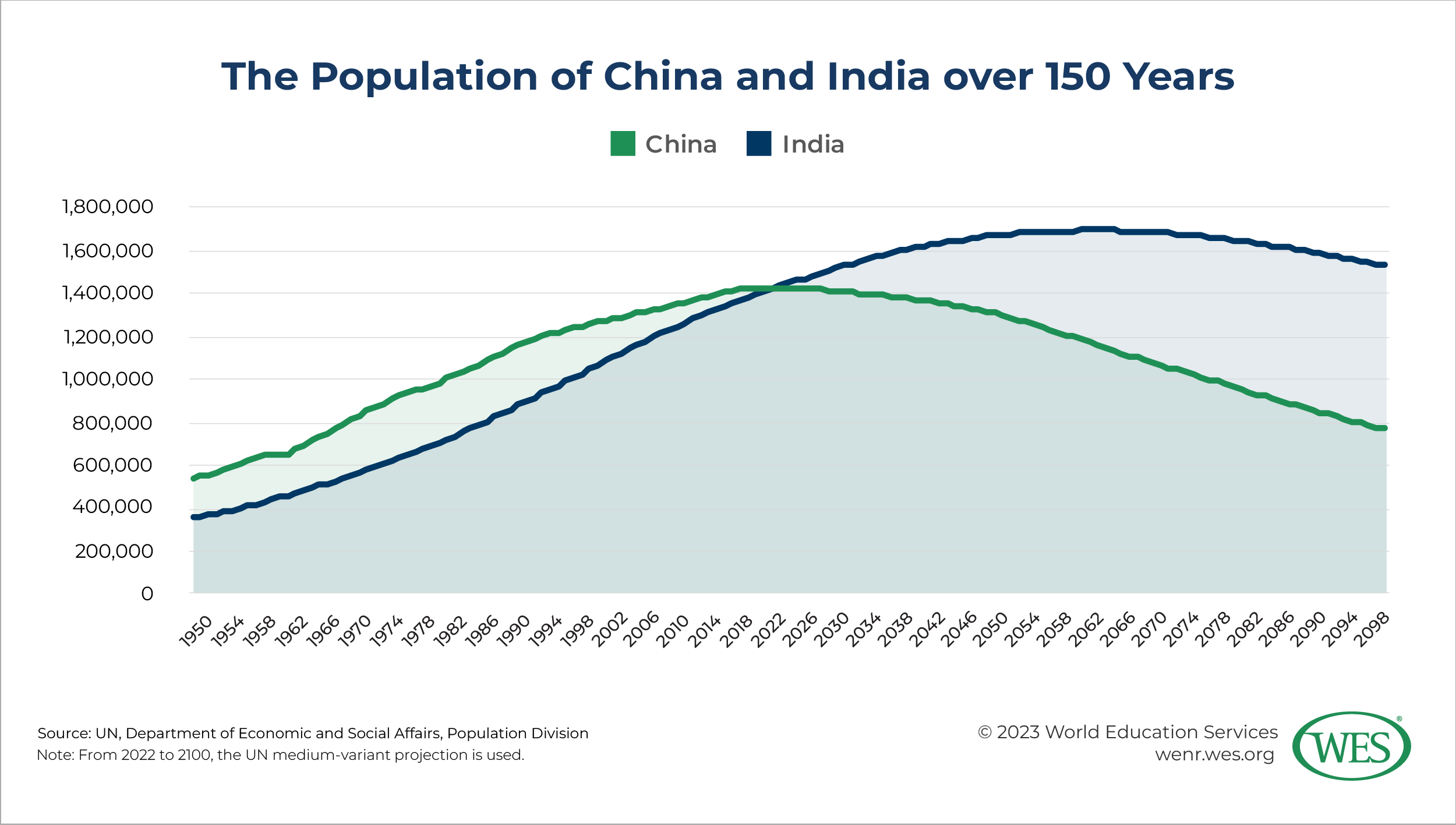

Since at least 1950, when the UN first began recording national population figures, China has boasted the world’s largest population. That changes later this year.

According to the UN’s latest population estimates [3], India will surpass China as the world’s most populous country by the middle of 2023. In the decades to come, the gap between the two countries’ populations will only grow. The UN projects China’s population to shrink by almost half by the end of the century, falling from 1.426 billion today to around 771 million in 2100.

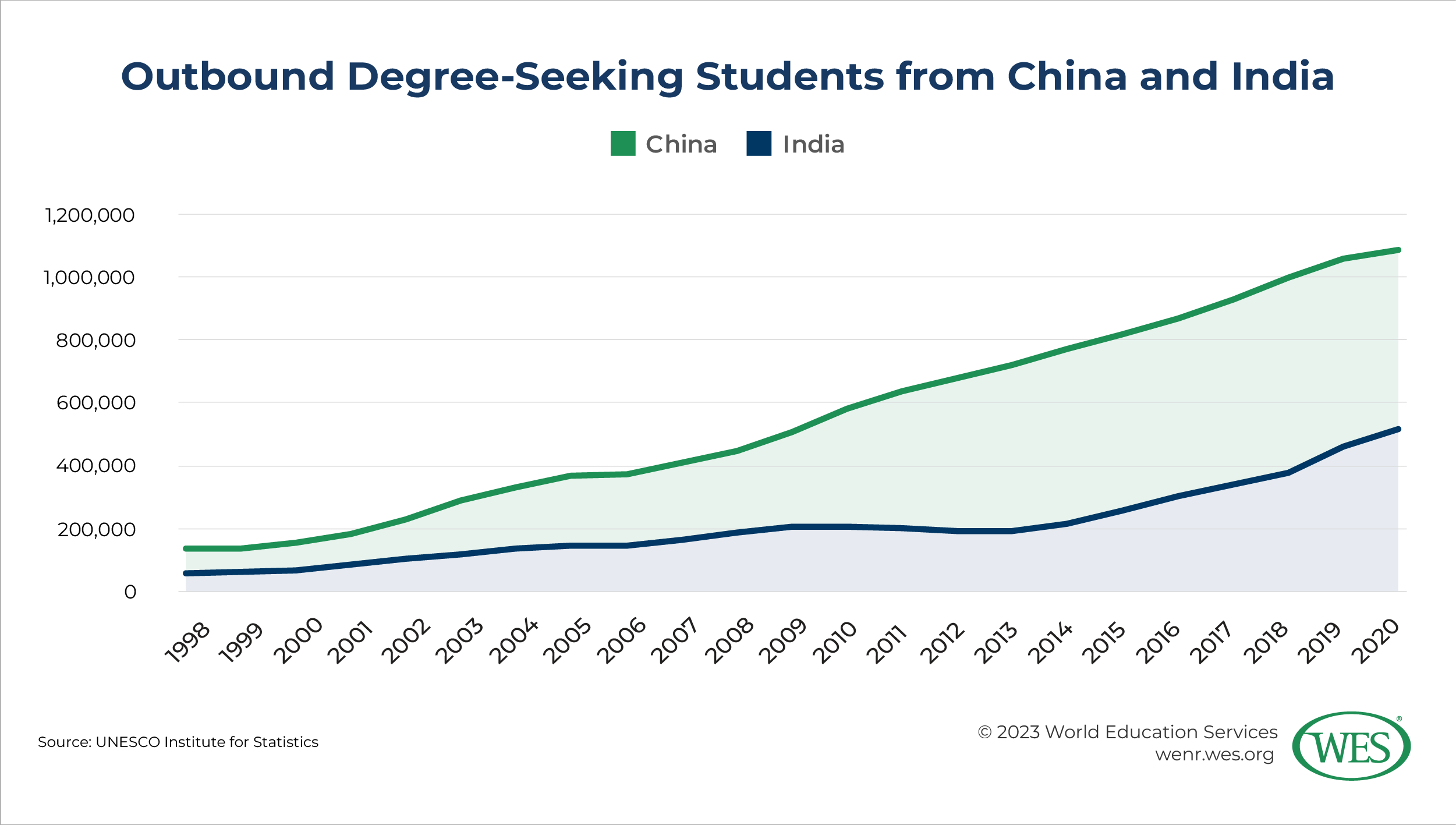

But in other matters, China remains on top. Since 1998, when the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) first began recording global student mobility figures, China has been the world’s largest source of international students. In 2020, nearly 1.1 million [5] Chinese students pursued a university degree outside of the country, more than twice the number of students coming from India, the next largest source. That year, Chinese students accounted for one out of every six (17.1 percent) globally mobile degree-seeking students.

In the United States, Chinese nationals make up an even higher proportion. In 2021/22, they accounted for 30.6 percent [7] of all international students in the country, compared to 20.9 percent for Indian students.

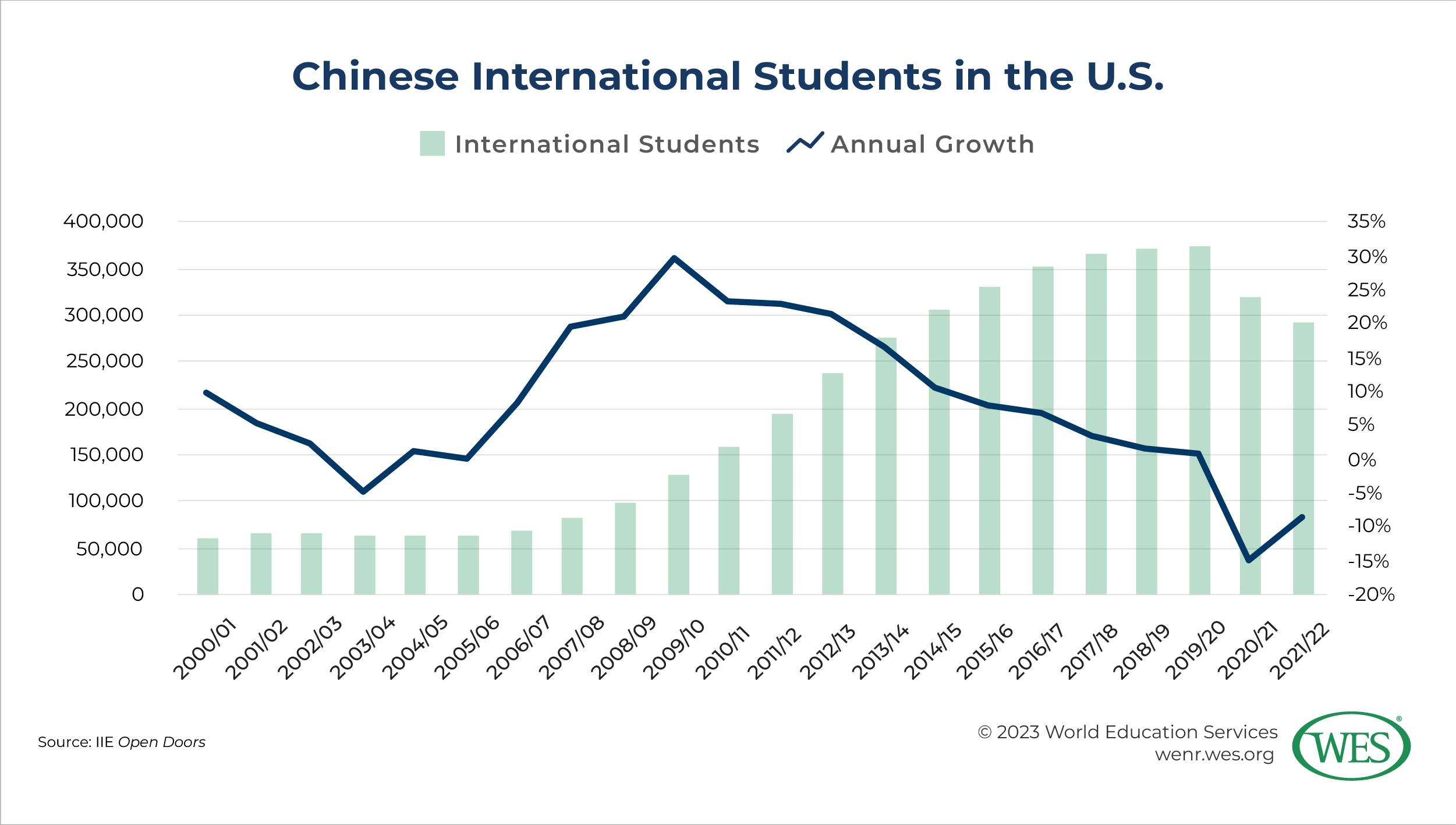

But how much longer will China remain the top sender? Industry experts have warned for years that the dramatic upswing in Chinese international student numbers was coming to an end. Data back them up. Although total Chinese international student enrollment in the U.S. grew every year between 2009/10 and 2019/20, year-over-year enrollment growth slowed steadily, falling from 29.9 percent [7] to 0.8 percent over that same period. Over the next two years, with the pandemic wreaking havoc on global mobility, the number of Chinese students enrolled in the U.S. fell precipitously.

Given China’s prominence as the U.S.’s largest source of international students, untangling the unique set of factors impacting the outbound flow of Chinese students is vital to understanding and preparing for the future of global student recruitment.

To shed light on the topic, this article, Part I of a multi-part investigation, examines some of the major forces affecting the mobility of Chinese international students to U.S. colleges and universities. Our investigation begins with the pandemic. Although the worst days are behind us, the virus has fundamentally reshaped the international education landscape, and the containment measures adopted by Chinese authorities have had a unique and lingering impact on international student mobility. Part I continues with an exploration of the increasingly strained relationship between the governments of China and the U.S.; it ends with an examination of some of the troubling attitudes and realities that characterize U.S. society today.

Later articles in the series will investigate some of the prominent trends in China and around the world that are shaping Chinese student mobility to the U.S. These upcoming articles will also explore what U.S. colleges and universities can do to address current and future challenges and to create an inviting atmosphere for Chinese international students.

With U.S. campuses potentially facing the simultaneous decline of both Chinese and domestic student [9] enrollment in the coming years, a nuanced awareness of the conditions impacting the world’s largest source of international students will be key to developing institutional resilience.

The Pandemic and Government Containment Policies

For much of the past three years, China had been an outlier. While countries around the world adjusted their containment strategies to the ebb and flow of the virus, the Chinese government, until recently, held fast to a strict zero-COVID policy.

This policy had a profound impact on current and prospective Chinese international students. It contributed to a dramatic drop in the number of Chinese students studying at U.S. institutions, an enrollment decline unparalleled by that of other countries. And, although the central government reversed course in late 2022, the impact of its zero-COVID policy lingers today—both in the continuation of selective pandemic-era policies and in the decision-making of prospective Chinese international students. Because of the profound impact of the zero-COVID policy on the flow of Chinese students to the U.S., we open our investigation of the future of Chinese international student mobility with an in-depth look at China’s response to the pandemic.

Under China’s zero-COVID policy, government health authorities adopted aggressive control measures aimed at reducing the incidence of the virus within the country to zero. To detect and track infections, public health officials mandated regular coronavirus testing and developed a rigorous system of contact tracing. Following the discovery of an outbreak, government officials moved aggressively to restrict its spread, mandating isolation of infected individuals and even locking down affected neighborhoods or entire cities until an outbreak was under control. In the country’s largest lockdown, authorities confined [10] Shanghai’s 25 million residents to their homes for more than a month in the spring of 2022.

Rigorously enforced restrictions on cross-border movement supplemented these domestic controls. To ensure that no one brought the virus into China from abroad, the government introduced regulations requiring all international travelers arriving in the country to quarantine for long periods. Until late June 2022, inbound travelers had to isolate for two weeks at a government-run quarantine facility after landing in China, followed by an additional week of quarantine at home.1 [11]

International travelers were also required to take additional precautionary measures prior to their flight’s departure. Government regulations [12] demanded that inbound passengers take a coronavirus test seven days prior to their flight. Over the next week, travelers would need to take up to four additional tests depending on their vaccination status. All these tests needed to be conducted at a laboratory recognized by the Chinese government in the traveler’s departure city.

These pre-departure requirements were more difficult to meet than they might appear at first glance. Following the outbreak of the pandemic, falling demand for global travel and government mandated flight suspensions [13] prompted international airlines to slash service to and from China. Between January 2020 and January 2022, the number of weekly flights arriving in Chinese airports from abroad fell [14] from around 10,000 to less than 500.

The number of airports serving direct flights to China declined as well. By April 2022, airports in just six U.S. cities offered direct connections to China. Because regulations required that international travelers get tested at laboratories in their departure city, out-of-town travelers first had to go to and stay in one of these cities for at least a week prior to their flight’s scheduled takeoff.

These policies made it exceedingly difficult for Chinese international students to return home from their studies overseas, whether after graduation or during breaks. Unsurprisingly, students who braved the long periods of required isolation reported that the experience had harrowing effects on their mental health [15]. It even prompted some to abandon their studies in the U.S. entirely. Reports of their hardships likely influenced others to rethink their plans for international study in the first place.

Complying with these regulations could also prove costly. Reports suggest that the total cost of the government-recognized COVID-19 tests could reach up to US$400, while seven days of pre-departure accommodations for out-of-town travelers was likely far more costly. Most expensive of all were the plane tickets themselves. With fuel and labor costs rising and flights to China scarce, airfare to the country could run as high as $5,000 [16]—10 times higher than before the pandemic.

These travel restrictions even raised expenses for those Chinese international students who didn’t—or couldn’t—return home. With most dormitories closed for summer and winter breaks, many Chinese international students had to scramble to find housing [17] amid a nationwide housing shortage. Visa restrictions limiting employment opportunities and rapidly rising rent prices made meeting these unexpected housing and other living expenses even more difficult.

These measures severely disrupted the flow of Chinese international students to the U.S. Following the initial outbreak, Chinese international student enrollment declined at a rate similar to that of international students from the rest of the world. In 2020/21, the first year that followed the outbreak of the pandemic, Chinese enrollment in the U.S. declined 14.8 percent, while enrollment from all other countries combined declined 15.1 percent.

But the next year, as most other countries began relaxing their COVID-19 restrictions, Chinese international student enrollment numbers began to diverge sharply from those of the rest of the world. While non-Chinese international student enrollment grew by 10.3 percent between 2020/21 and 2021/22, Chinese enrollment continued to decline, falling an additional 8.6 percent. Although still the largest source of international students, the 290,086 Chinese students in the U.S. that year was down more than a fifth [7] from its peak just two years before.

However, as noted above, the Chinese government has almost completely revised its approach to the virus in recent months. In response to nationwide protests, Chinese officials began loosening COVID-19 restrictions in early December 2022. On January 8, 2023, the Chinese government further relaxed its containment measures, removing most international travel restrictions [18], including its quarantine requirements for inbound travelers.

Despite this reversal, many effects linger. For one, the lifting of international quarantine restrictions, announced on December 26, 2022 [19], likely came too late for many students to apply for fall 2023 admission at a U.S. institution.

Additionally, travel costs remain elevated, as flights between China and the U.S. have yet to recover their pre-pandemic frequency. In March 2023, the number of international flights arriving in China was just a quarter [20] of what it had been in 2019. Flights between the U.S. and China are likely to remain limited for the foreseeable future, as the governments of both countries remain attached to the pandemic-era suspensions they imposed on each other’s flights.

The U.S.-China Geopolitical Relationship

The decision of both the U.S. and Chinese governments to maintain restrictions on the other’s international flights highlights a considerable source of uncertainty about the future of Chinese international student mobility: geopolitical tension between the two countries.

Myriad points of contention [21] divide the U.S. and China: trade and tariff disagreements, territorial claims to the South China Sea, the treatment of Uyghurs in Xinjiang, the level of Hong Kong’s political autonomy, the status of Taiwan, and, most recently, the war in Ukraine.

Suspicion extends to other sectors as well. In the U.S., government officials view Chinese involvement in research and higher education with growing skepticism and have introduced a series of measures aimed at limiting the influence of the Chinese government on university campuses. In recent years, the federal government has aggressively targeted Confucius Institutes, which officials contend “exert malign influence [22] on U.S. campuses and disseminate CCP propaganda.” In 2021, lawmakers introduced [23] a provision in the National Defense Authorization Act requiring that universities terminate their contracts with Confucius Institutes or lose eligibility for defense research grants. While the provision allowed universities to obtain a waiver to continue the partnership,2 [24] most institutions elected to shutter their Confucius Institutes rather than risk losing access to government funding. As a result of this and other measures, only about a dozen [25] Confucius Institutes still operate in the U.S. today, down from well over 100 just a few years ago.

Government suspicion has also been leveled more directly at Chinese international students and scholars, especially during the Trump presidency. In 2018, FBI Director Christopher Wray, testifying before Congress, warned [26] that China is increasingly turning to “nontraditional collectors, especially in the academic setting, whether it’s professors, scientists, students” to carry out espionage activities.

That same year, the Justice Department launched the China Initiative [27], which focused on countering Chinese economic espionage and trade secret theft. In the years that followed, the department opened thousands of investigations [28] into alleged incidents of Chinese espionage, many of which targeted academics and researchers who had Chinese affiliations.

But the program was dogged by controversy from its inception, with critics alleging that it unfairly targeted professors of Chinese and Asian descent. In response, the Biden administration discontinued [29] the program in early 2022, but not before the lives and careers [30] of hundreds of mostly Chinese-born scholars had been destroyed. Even today, Chinese and other Asian American academics hesitate [31] to apply for federal research grants.

While the Biden administration has taken a less hostile approach to Chinese students and scholars than the Trump administration, it has still elected to maintain some of the latter’s policies. For example, despite complaints from academics, policymakers, and others, the Biden administration has already twice extended [32] an executive order issued by the Trump administration that terminates [33] the U.S. Fulbright program in China and Hong Kong.

The Biden administration also declined to rescind [34] a 2020 Trump policy that denies visas [35] to Chinese graduate students who had previously studied at a university connected with China’s military. In 2021, nearly 2,000 Chinese students [36] had their visas denied under the policy. The policy likely dissuaded other prospective Chinese students from even applying. A February 2021 report [37] estimated that the policy would deny visas to 3,000 to 5,000 Chinese students—or about one-fifth of all new Chinese enrollments in U.S. graduate STEM programs.

China has responded in turn, intensifying its scrutiny of international organizations, including international universities that operate in the country. In the past few months alone, the Chinese government has expanded [38] its anti-espionage law, raided [39] the offices of international businesses, and increased its reliance on exit bans [40] to keep both Chinese citizens and international visitors from leaving the country.

Chinese organizations, at the encouragement of the government, have also moved in recent months to limit out-of-country access [41] to previously public information about China. For example, in April 2023, China National Knowledge Infrastructure the company that maintains China’s largest database of academic journals, severely restricted international access [42] to many of its resources.

According to experts, these actions are driving a wedge between the science and higher education communities of China and the West, risking a decoupling [43] that they warn will create “unprecedented problems” for universities around the world. Deteriorating relations will not only disrupt university-to-university research collaboration but will also obstruct the flow of Chinese students to U.S. universities. Reports already suggest that Chinese students in the U.S. are taking precautions [44] to protect themselves from the expanded anti-espionage laws introduced in China just a few weeks earlier.

Deteriorating relations between the two countries could be especially detrimental to Chinese graduate and doctoral students, who are among the most productive researchers [45] at U.S. institutions. Chinese students have also long filled a large proportion of seats in U.S. graduate programs. In 2021/22, Chinese students accounted for 31.9 percent [46] of all international students enrolled in a U.S. graduate program, the highest among all international students. But that too may already be changing. In the fall of 2021, India passed China [47] to become the leading source of new international graduate students in the U.S.

The Sociopolitical Environment in the U.S.

Political tension has, at times, colored public perceptions [48] in both countries. In mainland China, public opinion is growing more nationalistic, even anti-American [49], while in the U.S., attitudes toward China are increasingly antagonistic. A March 2023 poll [50] by the Pew Research Center found that 83 percent of U.S. adults held a negative view of China, including a full 38 percent who view China as an enemy of the U.S.

Sadly, these attitudes extend, at least in part, to Chinese international students as well. A February 2021 Pew survey [51] found that 55 percent of U.S. adults support limiting the number of Chinese students who are allowed to study in the U.S.

Even more troubling is a rise in anti-Chinese and anti-Asian sentiment. Between 2020 and 2021, anti-Asian hate crime grew by 339 percent [52]. In the latter year, a shocking one in six Asian American adults [53] reported experiencing a hate crime.

Among Chinese international students, the rapid increase in discriminatory acts is reinforcing long-held concerns about personal safety abroad. Security has long been a major concern of Chinese international students and their families. In a recent survey [54], more than half (54 percent) of prospective Chinese international students identified safety as a key factor in their choice of institution. That same survey found that 44 percent of prospective Chinese international students and 53 percent of their parents were concerned about discrimination during their stay abroad. An even larger proportion (46 percent of Chinese students and 57 percent of Chinese parents) were worried about crime.

While the attitudes expressed in that survey reflect general worries about the risks of study abroad in any country, the unique prevalence of gun violence in the U.S. likely means that safety concerns are even more of an urgent matter for students considering an institution in the U.S.

Chinese international students, like others around the world, are well aware of the dangers of gun violence in the U.S. In February 2023, a gunman opened fire on students at Michigan State University, killing three and injuring five; two international students from China [55] were among the injured. This tragedy, and others like it [56], receive extensive [57] coverage [58] in the Chinese media.

Understandably, these incidents worry Chinese international students and their families. Earlier research [59] from World Education Services (WES) found that while international students generally feel safe from physical and verbal harm when studying in the U.S., they have significant concerns about gun violence. East Asian students were among the most likely to express anxieties: More than a quarter (28 percent) are worried about gun violence at their institution, while more than two in five (41 percent) were concerned about gun violence in the local community.

Unfortunately, these anxieties are unlikely to wane any time soon. In fact, with recent U.S. Supreme Court rulings making it more difficult [60] for states to regulate gun ownership, gun violence may become a growing issue in the years to come.

Looking Beyond the U.S.

For Chinese students considering higher education in the U.S., gun violence is just one of the unique risks they may face. Political enmity, although to a lesser degree present between China and other countries, is another. In an interview [61] with the Financial Times, a Chinese educational consultant noted that geopolitical tensions have made parents in China “afraid their kid may not be able to complete their education.” Under these conditions, as the author notes, studying anywhere other than the U.S. is becoming an increasingly attractive and prudent prospect.

The following article in this series will explore the global scramble for Chinese students. As the U.S. grapples with unique recruitment obstacles, major players around the world, including China, have increased their efforts to attract and enroll Chinese students.

Subsequent articles in the series will also explore what colleges and universities can do to mitigate the unique risks of studying in the U.S. and to adapt to the ever-changing international education landscape.

1. [62] After June 2022, passengers arriving in China were only required [63] to isolate for seven days in a quarantine facility and three days at home.

2. [64] The Department of Defense only opened applications for the Confucius Institute Waiver Program [65] in March 2023.