One of the assumptions that is driving the interest in micro-credentials is that flexible and easily obtainable learning experiences, tailored to specific needs and industries, can help workers adapt to new demands in a fast-changing labor market and narrow the gap between skills required by employers and those provided by formal education. What’s more, the current discussions about micro-credentials are often framed in terms of social inclusion. In 2020, for example, a report commissioned by the European Commission described micro-credentials as a means to “democratize knowledge [3].” Micro-credentials could, the report contended, create lifelong learning opportunities and improve the employment prospects of a diverse population, including long-term unemployed individuals and adults affected by the digitalization of work and other changes in the labor market [4].

Others view the mainstreaming of bite-sized learning experiences as a devaluation of the traditional university “macro” degree and see micro-credentials as a market- and profit-driven commodification and genericization of education within a neoliberal learning economy. American scholar Shane J. Ralston, for example, has argued that the current “microcredentialing craze [6]” doesn’t foster inclusivity but could rather exacerbate social divisions by ushering in a future in which holistic liberal arts university education is solely the privilege of wealthy elites, whereas the less fortunate will be relegated to accumulating a series of narrowly focused skills certificates, the content and standards of which are mainly set by industry.

Irrespective of one’s attitudes toward the rising trend, the current flood of micro-credentials and digital learning certificates creates challenges for credential evaluators. Professionals in the field are accustomed to assessing benchmarked credentials that can be placed within qualifications frameworks and have clearly defined academic levels, admission requirements, credit units, and learning outcomes—attributes that do not apply to many of the new types of short-form learning certificates.

To date, micro-credentials have not been commonly accepted as a form of academic or vocational “currency” in most parts of the world. The work of most international credential evaluators in the United States and Canada remains centered on the assessment of formal academic qualifications for the purposes of university admissions, licensing, or immigration. However, the growing prominence of micro-credentials cannot be ignored. Should micro-credentialing prove to be more than a passing trend and become mainstreamed and socially accepted on a larger scale, credential evaluation services will most likely have to follow suit to meet the demand for the assessment of credentials beyond traditional degrees and other standard academic qualifications.

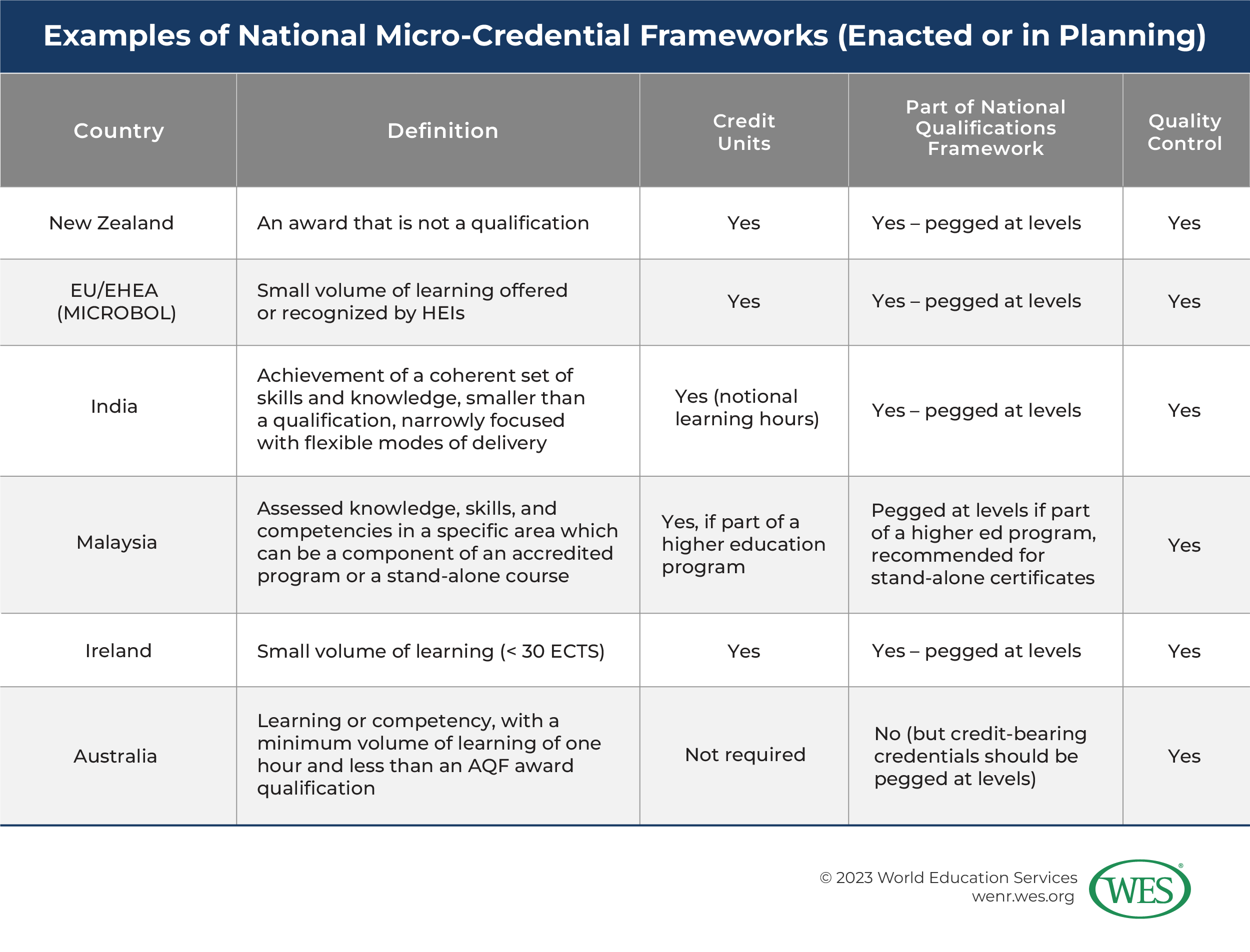

To take stock of how education systems are responding to the current rise of micro-credentialing, this article reviews the approaches to formalizing and benchmarking micro-credentials that have been developed by regulatory authorities and other stakeholders in New Zealand, Australia, Canada, and the European Union. These strategies reflect growing interest among governments and academic institutions around the world in setting baseline standards, increasing transparency, and establishing quality assurance processes in the mushrooming and unregulated micro-learning sector.

In the conclusion of this article, we will discuss how these strategies and policies can orient and provide guidance to international credential evaluators when assessing micro-credentials. First, however, we will briefly touch upon issues of definition related to micro-credentials and the scope and size of the micro-learning market.

What Are Micro-credentials?

While micro-credentials are generally understood as the certification of a small amount of learning, there’s no universally accepted standard definition of a micro-credential (MC). It is a loosley defined term that can mean different things to different people—from Microsoft skills certificates or LinkedIn learning certificates issued in the form of a digital badge, to individual modules or study units taught or recognized by higher education institutions and designed to be “stacked” or combined to earn a traditional (macro) degree or other formal qualification.

Some forms of education that were previously labeled “continuing education” programs have been re-branded and are now offered as MCs. Some may consider a MOOC an MC, while others define a MOOC as a smaller “nano credential,” and so on. Some definitions of MCs focus on online delivery and digital certification, while others encompass blended and face-to-face learning. What dilutes the category even more is the multitude of providers, ranging from digital education platforms to universities, corporations, trade associations, and labor unions.

Further adding to the terminological confusion is the fact that some edtech companies have trademarked their own terms [7], some of which describe more substantial offerings beyond MOOCs. Udacity, for example, owns the rights to the term “nanodegree [8]” (a fee-based three- to four-month online program) while edX has trademarked the “micromasters [9]” (a self-paced series of online graduate-level certificates that may articulate into a master’s program [10]). Other more esoteric terms include “über badges,” “summit badges,” or “meta-badges” that certify either the accumulation or hierarchical stacking of sub-badges [11].

As discussed below, several countries now have initiatives underway to define, regulate, and benchmark MCs. Even though these countries view MCs as complementary to traditional education programs or as alternative forms of education, they simultaneously seek to establish structure in the micro-credentialing ecosystem by introducing standard elements of traditional education programs for assessment, such as credit units, level descriptors, and quality assurance.

For credential evaluators, these developments are welcome, as the present landscape of MCs resembles that of a “jungle of certificates”—a fast-growing thicket of mini credentials that are difficult to assess. The systematic comparison, academic placement, and equalization of many of the micro-learning certificates in current circulation is a challenge at best, and an impossibility at worst. Consider that many MCs are characterized by the following attributes:

- No (or limited) formal academic admission requirements. While in some cases entry may be tied to specific academic requirements, minimum age requirements, or the completion of prior certificates (in the case of a stacked sequence of certificates), many micro-credential courses are open to all. Designed as open-access forms of lifelong learning, they lack the academic admission requirements central to merit-based formal education qualifications.

- No quantification or measurement in defined and common units of study. The required length of micro-learning is often set forth in hours or days, sometimes weeks; other learning experiences are self-paced without any specified learning time. This type of learning does not generally conform to existing measurements of study, be they Carnegie Units [12], ECTS credits [13], or otherwise—a fact that makes it very difficult to compare one certificate to the next, or transfer acquired learning experiences from one setting to another.

- No academic level. Micro-learning is usually not pegged at established levels of academic or vocational qualifications frameworks. As illustrated by the lack of admission requirements, micro-learning certificates usually cannot be classified in concrete categories, such as secondary, undergraduate, graduate, first or second cycle, UNESCO ISCED [14] classifications, or the like.

- No quality assurance. Micro-learning is still largely unregulated and provided outside of established quality assurance frameworks and accreditation mechanisms. In most countries, almost anyone can offer informal online learning opportunities. Even when this type of learning is provided by recognized formal education providers, it may fall outside the scope of the accreditation granted. Hence, consistent minimum standards of quality do not exist.

- No consistent methods of assessment and criteria for award. While some certificates may require substantial examination or practical skills assessment for completion, others are awarded solely based on attendance, or the completion of a simplistic online quiz. This raises questions about what skills or knowledge learners have acquired, even in cases where learning outcomes are well-defined.

How Widespread Is Micro-learning?

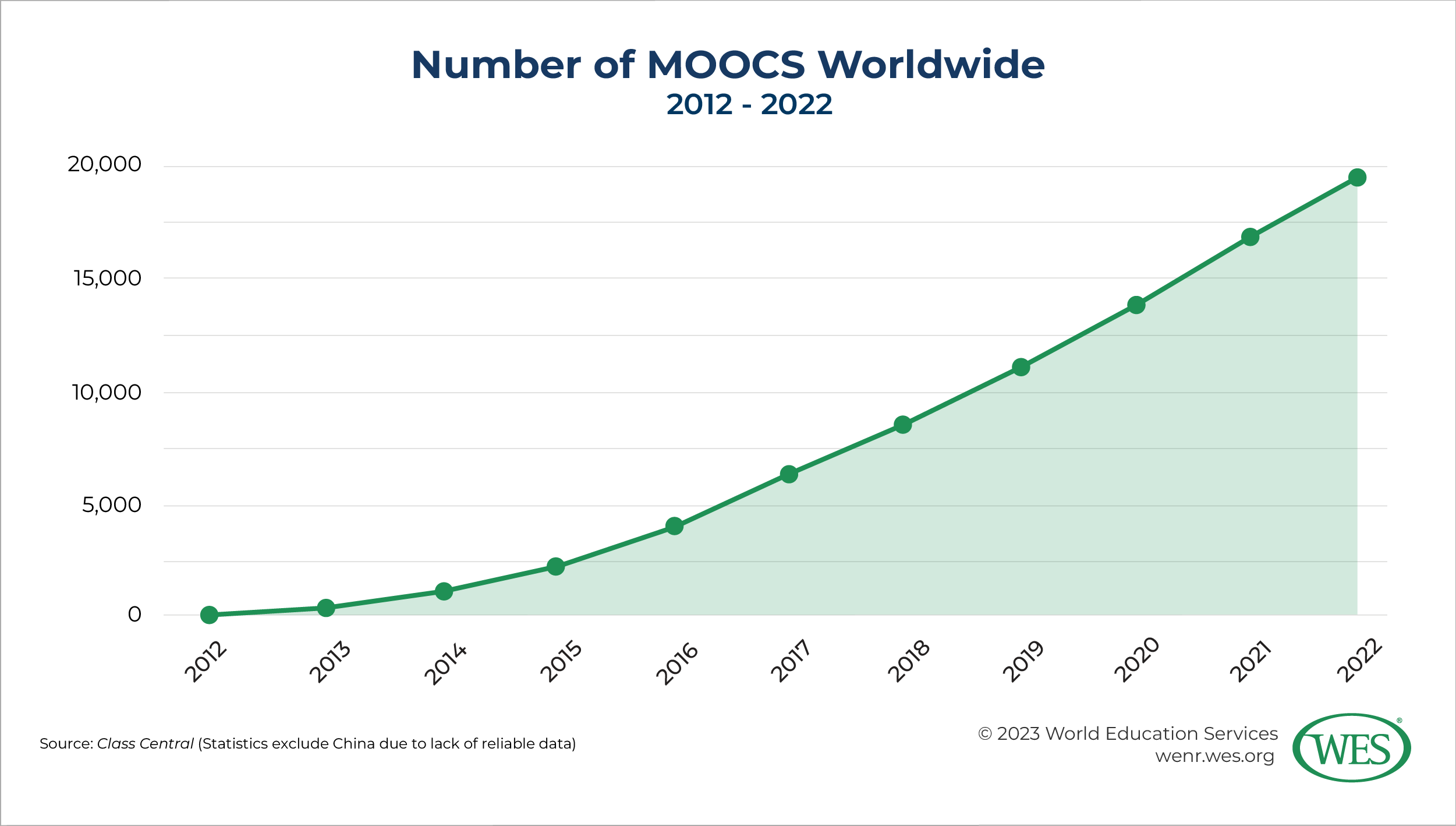

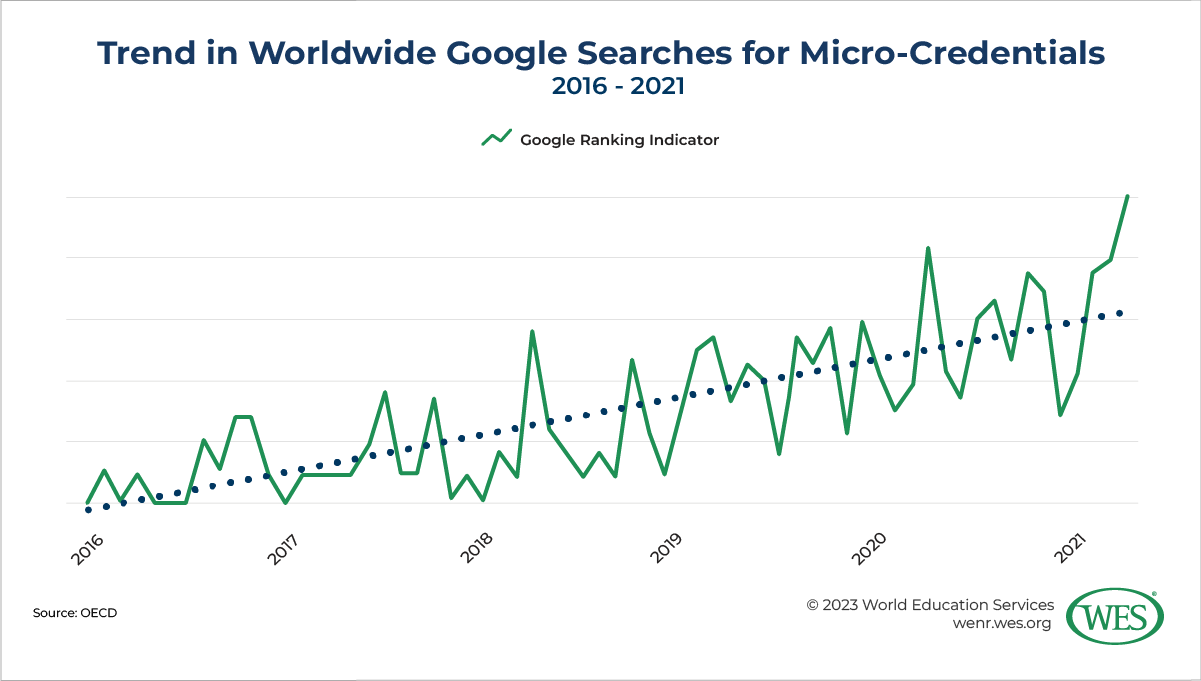

It is difficult, if not impossible, to approximate how many micro-learning offerings exist in various countries, let alone worldwide. What is clear is that this market is growing fast, although the post-COVID-19 return to face-to-face learning modalities may somewhat depress its rapid growth in recent years. Part of what’s driving the trend is that micro-credentials, as the OECD has noted, afford providers an inexpensive and low-risk opportunity for marketing and revenue generation while experimenting with new pedagogies and technologies [15].

The few tallies that exist underscore the substantial size of the sector. The U.S.-based research organization Credential Engine, for example, has counted 607,000 digital badges and online course certificates offered by non-academic providers in the U.S. alone in 2022 [16]—an increase of 20 percent over the number offered in 2021. U.S. academic institutions, by comparison, offered 58,342 non-credit-bearing certificate programs (up by 45 percent over those offered in 2021). These numbers likely represent undercounts, especially in the case of badges, given the complexities involved in tallying non-formal programs.

Other tallies of micro-credential that define MCs as MOOC-based programs offered via digital platforms such as Coursera, edX, FutureLearn, and Udacity, also reflect significant growth. According to Classcentral, a web directory of online courses, the number of these offerings increased from 1,500 in 2021 to 2,500 in 2022 [17].

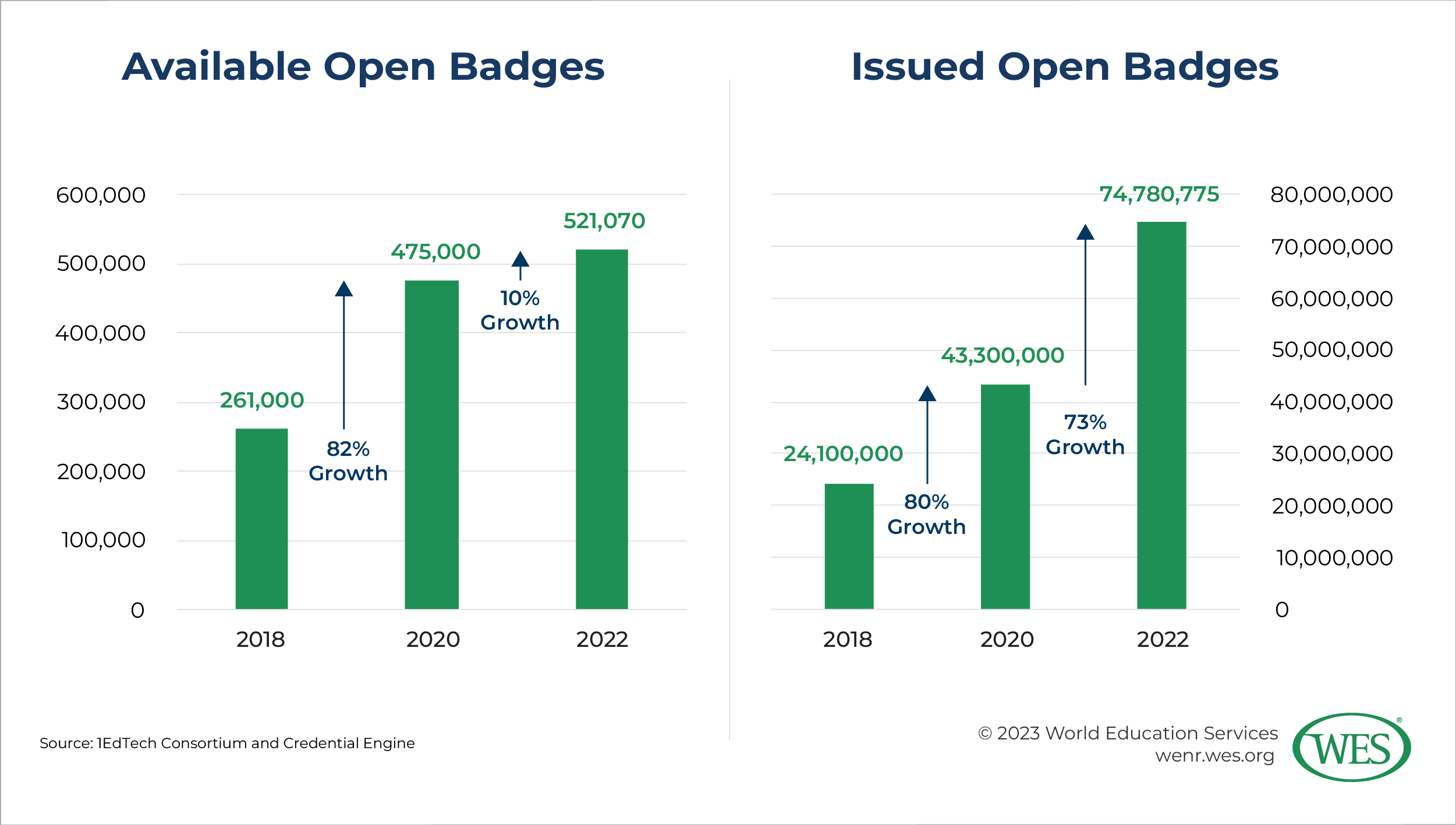

By some accounts, no less than 74 million “open (digital) badges”1 [18] have been issued worldwide thus far. And many more will be issued in coming years. Most available market research studies [19] on the size of the global alternative education market, including providers of non-credit-bearing certificates and digital badges, suggest that this sector is a multi-billion dollar industry, accelerating at double-digit growth rates annually, with North America having the biggest market share [20]. However, demand for micro-credentialing is booming in other world regions as well. A survey by the Asian Development Bank [21], for instance, found that fully 80 percent of job applicants in India and Bangladesh now submit some type of digital micro-credential with their job applications.

Approaches to Standardizing Micro-credentials

Over the past several years, governmental agencies, academic think tanks and international organizations like UNESCO and the OECD have put forward a flurry of position papers and policy proposals regarding micro-credentials. The governance approaches that have been developed and enacted in New Zealand, Australia, Canada, and the European Union are described below. However, other countries, including India [23] and Malaysia [24], have conceptualized similar frameworks.

Many governments welcome the concept of micro-learning and its promise of flexible, low-cost, employment-geared training for wider audiences of learners. At the same time, there’s a growing recognition that standardization and regulation is urgently needed in this sprawling sector. If micro-credentialing is to become the skills training engine that many envision it could be, it needs to be provided in a more structured, measurable, and quality-controlled manner.

New Zealand

Recognizing the need for standardization, New Zealand was one of the first countries to incorporate MCs into its formal education system. In 2018, the New Zealand Qualifications Authority (NZQA) established a framework for MCs with the aim of making them “more valuable and transferable for learners [26].”

The guidelines [27] set forth by NZQA require that providers that want to register MCs as recognized educational achievements within the New Zealand Qualifications Framework (NZQF [28]) must specify the amount of required credit units and specific learning outcomes, as well as the further education and employment pathways the credential affords. MC programs can be at most 40 credits in size (with one credit representing 10 notional learning hours, and 120 credits, one year of full-time study).

While New Zealand defines MCs as awards below a full-fledged qualification, MCs can only be delivered by recognized higher education institutions and schools and must be pegged at one of the levels of the NZQF. They can be designed to be stacked or combined and applied toward the award of a higher-level qualification. Micro-credentials in New Zealand have thus been established as nationally defined, quantifiable learning achievements of short duration that must meet set quality standards.

The number of approved MCs in New Zealand is still fairly small but growing fast. The official Register of NZQA-approved Micro-credentials listed 324 MCs [29] as of this writing, compared with 242 in 2022 [26]. Providers include accredited industry training organizations [30] and polytechnics, such as the private New Zealand School of Food and Wine, and the recently established public New Zealand Institute of Skills and Technology, New Zealand’s largest tertiary education provider [31]. MC programs are offered at both the secondary and post-secondary levels; common learning topics range from business, hospitality, and forestry to computer and software applications.

Australia

Australia has followed a similar approach to neighboring New Zealand. In 2021, it established a micro-credential framework in response to the growth of an incongruent micro-learning sector in the country. At that time, at least 36 out of 42 [32] Australian universities were already offering or developing some form of micro-credentials, and the federal Department of Education expressed concern that the governments of Australia’s states defined micro-credentials differently and “without a clear framework,” risking embedding “inconsistency into the future.” Adding to the confusion, it noted that “many providers have developed their own credit recognition or microcredential policies [33].”

Like New Zealand, Australia considers MCs as learning achievements below the level of a formal award qualification. Its micro-credential framework [34] defines MCs as the “certification of assessed learning or competency, with a minimum volume of learning of one hour and less than an AQF [Australian Qualifications Framework] award qualification.” MCs are “additional, alternate, complementary to or a component part of an AQF award qualification.”

To increase the comparability of MCs, the framework requires that MC programs specify necessary prerequisites (admission requirements, required level of experience), learning outcomes, content, and volume (number of hours), mode of delivery (on-site, online, or hybrid), as well as what type of quality assurance is applied, and what type of recognition the MC has (credits towards other qualifications, industry certification, or pathways to further education). Programs with “unassessed learning outcomes” and “badges obtained through participation only” are explicitly excluded from the framework.

One difference from New Zealand’s framework is that MCs can be awarded by organizations other than higher education institutions or vocational schools (Registered Training Organizations, or RTOs in the Australian context). The Australian approach has a strong focus on flexible skills training and encompasses offerings by non-formal education providers and “industry courses not currently accredited by a regulatory authority.” However, these providers must still disclose their quality assurance mechanisms and only higher education institutions registered with the national Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency (TEQSA) are listed in the country’s new MC directory, launched in late 2022 under the name MicroCred Seeker [35] (Microcredentials Marketplace).

As of April 2023, there were 408 MC courses listed in the MicroCred Seeker directory. Rather than being pegged at one of the AQF levels, MCs are categorized into five levels, from Novice to Advanced Beginner, Competent, Proficient, and Expert. The MC courses are between a few hours and several weeks, or even eight months (self-paced) in length. Close to half of them yield credits applicable to university programs; admission requirements range from open access to a bachelor’s degree.

Canada

In Canada, micro-credentialing has in recent years been adopted at a significant scale in the higher education sector with many universities and polytechnics now offering learning opportunities that are labeled as micro-credentials. One recent survey conducted by the British Columbia Council on Admissions and Transfer found that 22 percent [36] of Canadian institutions were considering offering some form of micro-learning. In 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, the province of Ontario promoted the development of micro-credential programming with a grant of C$59.5 million [37] over three years. There are now 1,776 MCs [38] offered by higher education providers in the province.

As in other countries, academic institutions in Canada view micro-learning as way to expand access to education and to foster upskilling and reskilling [39]. Beyond that, post-secondary institutions are “exploring alternative pedagogical delivery models, as well as alternative revenue streams [40] in the face of declining government funding, enrolment pressures, and economic uncertainties.”

Given the decentralized nature of Canada’s federal system, the country has not established a national micro-credential framework, or even a common definition of the term. However, several of Canada’s provinces have launched initiatives to define and standardize MCs, although the guidelines adopted in these jurisdictions are not as well-defined as those in New Zealand, for example. Quality control and approval of MC programs rests solely with academic institutions.

The province of British Columbia has adopted a micro-credential framework [41] for public higher education institutions that defines MCs as “short-duration, competency-based learning opportunities, that align with labor market or community needs and can be assessed and recognized for employment or further learning opportunities [42].” MCs are “shorter in duration than other post-secondary credentials (under 288 hours);” they can be “stackable and transferrable” and can be delivered online or face-to-face.

Ontario does not have an MC framework, but promotes the development of micro-learning and has made MCs eligible for public student aid. The province delineates MCs as “rapid training programs offered by colleges, universities and Indigenous Institutes across the province that can help … [learners] get the skills that employers need [43].” MCs, accordingly, take “less time to complete than degrees or diplomas,” and “may be completed online and may include on-the-job training.” In practice, MCs range from standalone five-hour “micro-credential badges” completed online to more substantial sequenced and stackable courses of more than 100-hour duration that can be used to obtain college credit or occupational certification. (Compare the eCampusOntario Micro-credentials Portal [44]).

In sum, while some Canadian provinces have moved towards greater standardization of MCs, they remain relatively loosely defined thus far. While recognized MC programs can only be offered by recognized post-secondary institutions, there are no level descriptors, no placement within existing qualifications frameworks, nor specific credit requirements, and programs can be credit-bearing or not.

The European Union and the European Higher Education Area

As in New Zealand, Australia, and Canada, many policymakers in Europe have welcomed micro-credentialing as a positive development. Along with digitalization, micro-credentialing has emerged as a frequent topic on policy agendas; references to flexible skills training and lifelong learning have become commonplace. At the same time, many policymakers have acknowledged that greater acceptance of micro-credentials will require changes in “mindsets, culture and structures,” and, as the European Commission has noted, a “common definition and a common approach on their validation and recognition [45].” In the context of the European Higher Education Area (EHEA), clear definitions and regulations are not only important for the recognition of MCs at the national level but also for their portability and transferability across the European Union.

In 2022, the Council of the EU recommended that member countries incorporate MCs into their formal education systems and adopt a common “European approach [46] to micro-credentials for lifelong learning and employability.” The council uses the following definition of MCs:

“Micro-credential means the record of the learning outcomes …. acquired following a small volume of learning. These learning outcomes will have been assessed against transparent and clearly defined criteria. … Micro-credentials are owned by the learner, can be shared and are portable. They may be stand-alone or combined into larger credentials. They are underpinned by quality assurance following agreed standards in the relevant sector or area of activity.”

While this definition is relatively broad and short on specific details, the European approach is still evolving, and more concrete proposals have been set forth specifically for the higher education sector. Most prominently, the EU-funded MICROBOL Project2 [18] has developed a micro-credential framework [47] based on the following summarized definition [48]:

“A micro-credential is a small volume of learning certified by a credential. In the EHEA context, it can be offered by HEIs or recognised by them. Micro-credentials have explicitly defined learning outcomes at a QF-EHEA/NQF level, an indication of associated workload in ECTS credits, assessment methods and criteria, and are subject to quality assurance.”

The MICROBOL proposal calls for the establishment of catalogues of MCs offered by registered providers, so that learners can “navigate the diverse offer across Europe.” Where possible, MC qualifications should be incorporated into national qualifications frameworks and learning outcomes be expressed in ECTS credits. In addition, it is proposed that MCs have:

- A Standard Format. This should be akin to an academic transcript/record/diploma supplement featuring identifying information on the learner and the provider/awarding institution, admission requirements, workload and learning outcomes, QF level, and forms of assessment.

- Quality Assurance and Recognition. Micro-programs should be incorporated into the internal QA mechanisms of higher education institutions, and the recognition of MCs should be based on institutional accreditation. While external program accreditation is commonplace in the EHEA, this approach is viewed as too burdensome for MCs. Instead of assessing the frequently changing MC offerings individually, external QA agencies should instead ensure that institutions providing them have solid internal QA mechanisms. It is also proposed that academic institutions can validate MCs offered by other non-academic providers or recognize them according to existing EHEA guidelines for the recognition of prior non-formal learning.3 [18]

Another similar EU-funded proposal, the Micro-Credential Users’ Guide [49] by the now discontinued MicroHe Consortium, suggests that academic institutions classify all their educational programs with a credit volume below 30 ECTS as MCs. Accordingly, MCs should feature a “credit supplement” that provides detailed information about the credentials. Among the options the Consortium envisioned is a system in which MCs are pegged to qualifications frameworks, so that they are “easily translatable … into local qualifications for the purposes of portability. Micro-credentials mapped to NQFs would effectively have the recognition status of ‘mini-degrees’, and could be used for purposes of admission and progression in higher education.”

Most countries in the EHEA have not yet adopted concrete regulations for MCs nor incorporated them into their national qualification frameworks. The recommendations by the European Commission are not binding for member states, and the creation of a more consistent policy on micro-learning across European countries is still an evolving process. That said, the overall trend in Europe certainly points toward the formalization and standardization of MCs in one form or another.

One example of this trend is Ireland, where the Irish University Association in 2020 launched the MicroCreds Project [50], which will make Ireland, as the association boasts, “the first European country to establish a coherent National Framework for quality assured and accredited micro-credentials.” According to this framework, MCs are small courses between 1 and 30 ECTS in size, accredited by universities and pegged at levels six to nine of the Irish Qualifications Framework (which corresponds to short-cycle undergraduate to master’s level). There are currently 2,330 credentials that fit these criteria listed in the register [51] of Quality and Qualifications Ireland (QQI), most of them either 10 or 15 ECTS in scope. (For a more in-depth analysis of Irish micro-credentials, see also an earlier report [52] by the QQI from 2021).

How to Assess Micro-credentials: A Credential Evaluator’s Perspective

The governance approaches surveyed in this article demonstrate that there’s a growing trend towards defining and standardizing MCs, as well as a certain degree of harmonization, in regions like Europe or Australasia. However embryonic some of these approaches may be, they will eventually help establish certain types of MCs as mainstream qualifications, and thus, as a currency that can be traded. The clear definitions and level classifications developed in Ireland, for example, are a boon from a credential evaluation perspective.

That said, a universal approach to MCs, or even a common definition of them, remains elusive. Globally speaking, credential evaluators still navigate a jungle of certificates in which frameworks are in a nascent or even non-existent state. While jurisdictions in some regions are seeking to institutionalize MCs as a part of their formal education systems, micro-credentialing in other countries is a Wild West of unregulated learning.

As micro-credentialing markets grow, evaluation agencies will receive more requests to assess MCs by holders of these qualifications, as well as by universities or employers—to evaluate and translate these credentials into local equivalents, to determine their credit value, and so on. The truth is that many of the micro-learning certificates in circulation cannot be assessed or equalized in a meaningful way. Without established standards, and transparent reliable information on the volume, content, and level of learning, how can one know if one micro-credential in, say, digital marketing represents the same amount and quality of learning, or a comparable attainment of skills, as another micro-credential issued by another provider in the same field?

Two approaches are central to assessing and equalizing credentials: functional equivalency and content equivalency. In the first case, we are analyzing and comparing the function of a qualification within the system of education: What type of further education does it give access to, what type of licensure or employment does it enable, where is it placed within the official hierarchy of qualifications, and so on. If a qualification—the micro-credential—does not have such placement, defined articulation pathways, or a concrete function other than that it may be informally accepted by some employers as proof of the acquisition of a certain skill, then a functional equivalency is difficult to determine. As with most academic qualifications, credential evaluators are largely dependent on the benchmarking of MCs within national frameworks.

In the second case, we are comparing the content of education, the curriculum and method of study or training. For example, we generally know what study and training a standard medical degree entails, or what a bachelor’s curriculum in mechanical engineering looks like, because these are established, standardized, and well-documented qualifications. In contrast to many MCs, we also know the level of education, the workload, how study is assessed, and whether the academic institution meets quality standards due to its accreditation status.

The existing obstacles should not, of course, deter credential evaluators from assessing all types of MCs. The profession needs to be open to the new forms of micro-learning and understand that assessing them requires flexibility. At the same time, evaluators should be mindful of the limitations of objectively evaluating non-standardized education. At present, only certain categories of MCs—for example, those that have been structured and classified in national frameworks according to set standards, or have at least been certified or validated by accredited education providers—lend themselves to systematic assessment and equalization.

As with other types of qualifications, evaluators need to research MCs to establish their recognition status and articulation pathways, and to determine if the learning can be quantified and classified by level—a task that should be facilitated by the different MC directories mentioned in this article, as well as by the “information supplements” that have been proposed for MCs in some countries. Evaluators may also find good use of available assessment tools, such as the Dutch NUFFIC’s Micro-Evaluator [54].

Over time, if current trends are a guide, micro-learning will likely evolve into a more structured form of education in a growing number of countries, making MCs more transparent, portable, and transferable. For example, it’s a positive sign for credential evaluators that just this year a regional micro-credential framework was proposed for Southern Africa [55].

1. [56] Defined by nonprofit 1EdTech as “information-rich visual tokens of verifiable achievements earned by recipients and easily shared on the web and via social media [57].”

2. [56] MICROBOL stands for “Micro-credentials linked to the Bologna Key Commitments.” The goal of the project was “for ministries and stakeholders to explore, within the Bologna Process, whether and how the existing Bologna tools can be used and/or need to be adapted to be fit for micro-credentials [58].”

3. [56] These guidelines are outlined, for example, in the 2015 ECTS Users’ Guide [59]. They recommend that institutions grant ECTS credits “for learning outcomes acquired outside the formal learning context through work experience, voluntary work, student participation, independent study, provided that these learning outcomes satisfy the requirements of their qualifications or components.”

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of World Education Services (WES).