This article is Part II of a multipart investigation into the shifts impacting Chinese international student mobility to the U.S. Read Part I [2] here.

Part II: Economy and Society in China

In early 2023, researchers at the University of Science and Technology of China announced [3] a breakthrough: a more than 10-fold increase in the rate at which quantum keys can be securely transmitted between two parties for encryption purposes. This advance could have major implications [4] for the future of communications. The research team achieved a pace and range of transmission that could move one of the most mature quantum technologies from the laboratory to the real world.

Although occurring in a niche field, this innovation is just one of the many technological advances that have catapulted China to a preeminent position on the world stage. Since the start of the twenty-first century, these developments, along with China’s growing economic, military, and diplomatic strength, have transformed the trajectory of the nation, both internally and in its relationship with the outside world. With respect to education, China has revamped domestic learning, investing billions to develop a handful of top globally renowned universities, while actively promoting the inward and outward flow of students and scholars across its borders.

But today China stands on the brink of a new era. As long-term demographic and economic trends intersect with a potentially violent realignment of global politics, China’s near future, and the future shape of Chinese student mobility to the United States, could look very different from its recent past.

This article, Part II of our multipart investigation into the shifts impacting Chinese international student mobility to the U.S., examines some of the most consequential socioeconomic developments in China today. Beyond any future cataclysmic breakdown in the U.S.-China relationship, nothing will impact Chinese international student flows more than developments in China itself.

The Chinese Century

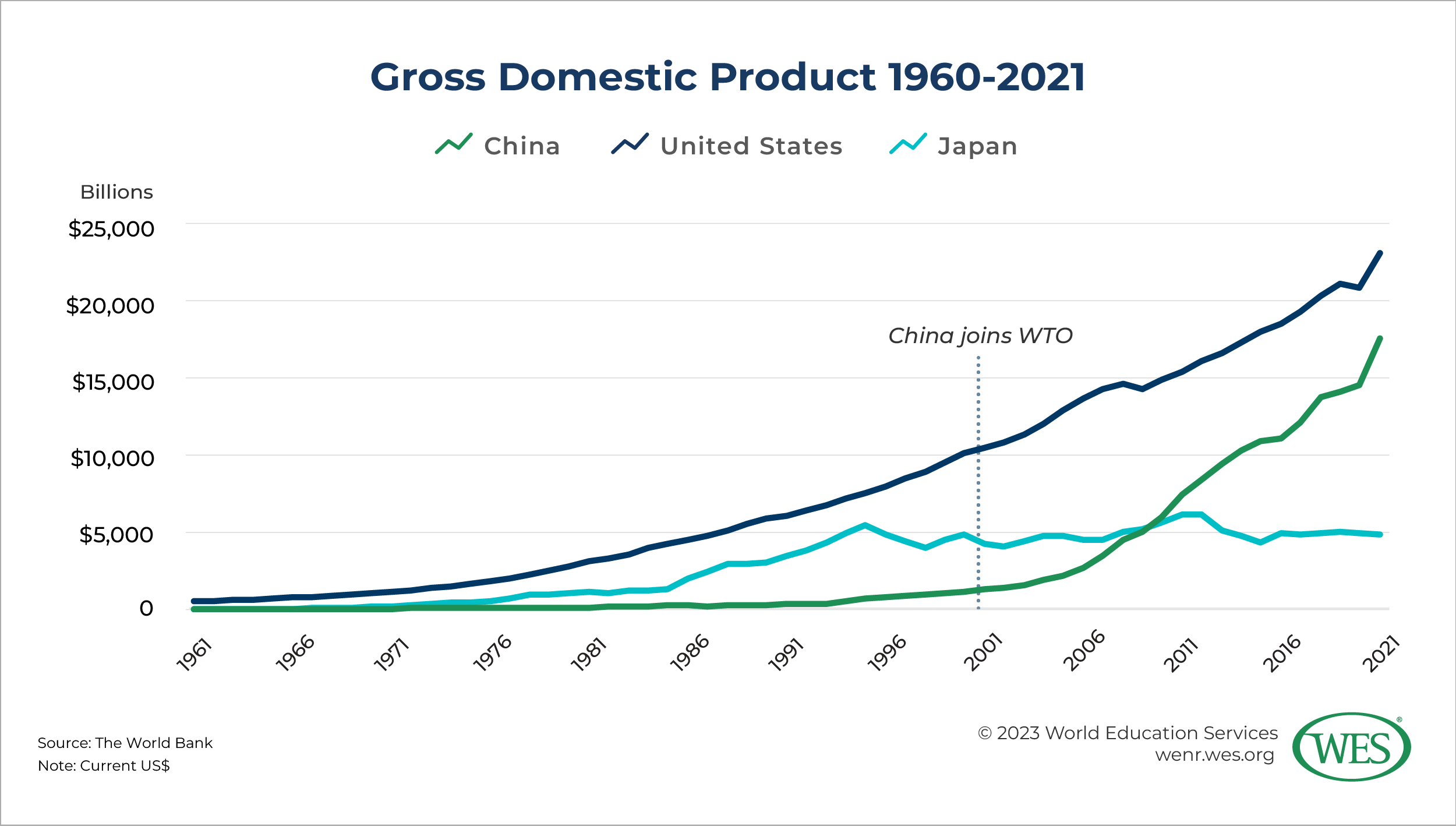

Rapid growth has defined China’s economy since the beginning of the twenty-first century. Since the nation joined [5] the World Trade Organization in December 2001—an event often identified [6] as the start of the nation’s spectacular rise on the global stage—Chinese businesses have boomed. By 2010, China’s economy had surpassed [7] Japan’s as the world’s second-largest. By 2030, most experts have predicted, it would pass the U.S.’s to become the world’s largest.

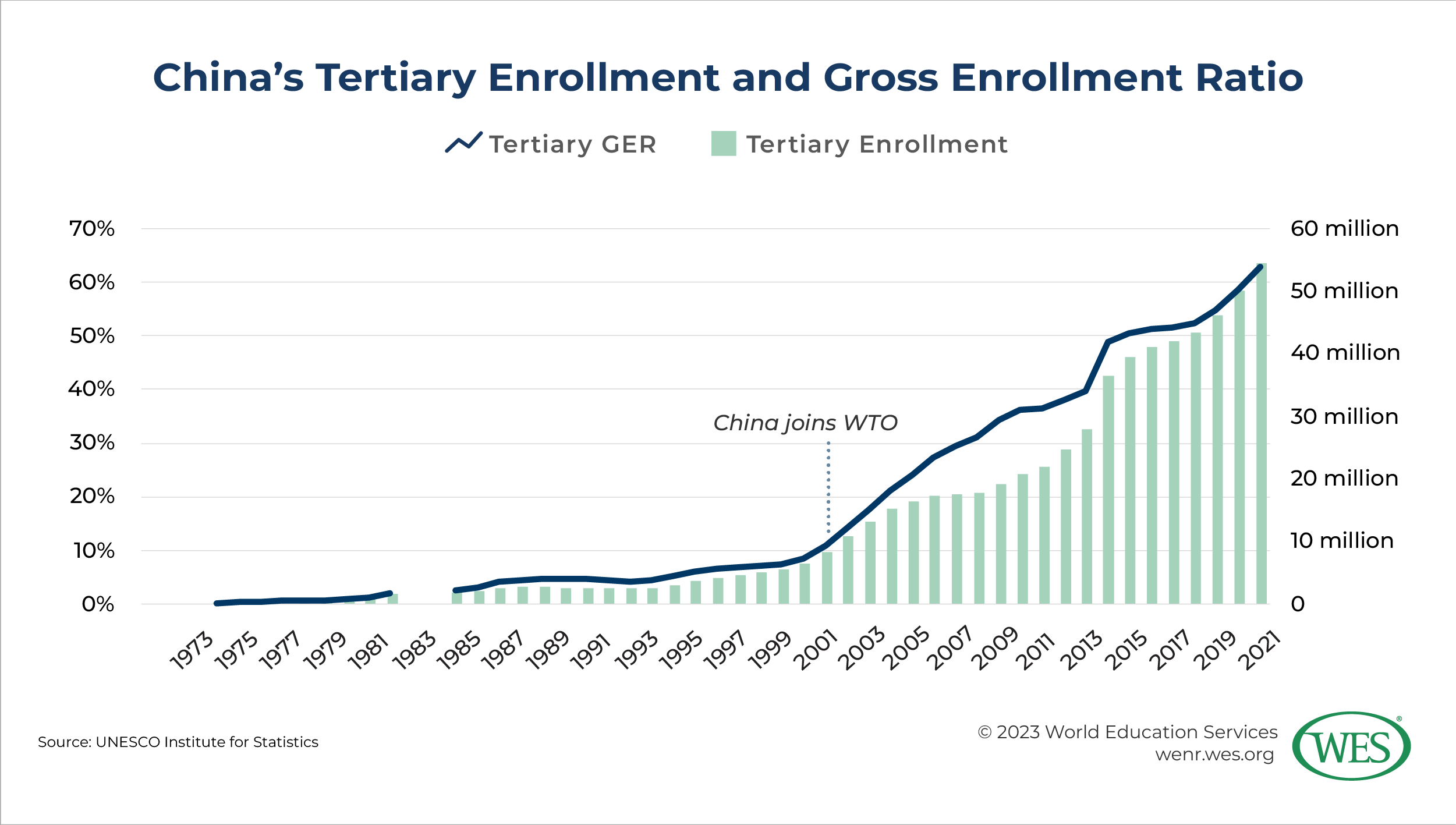

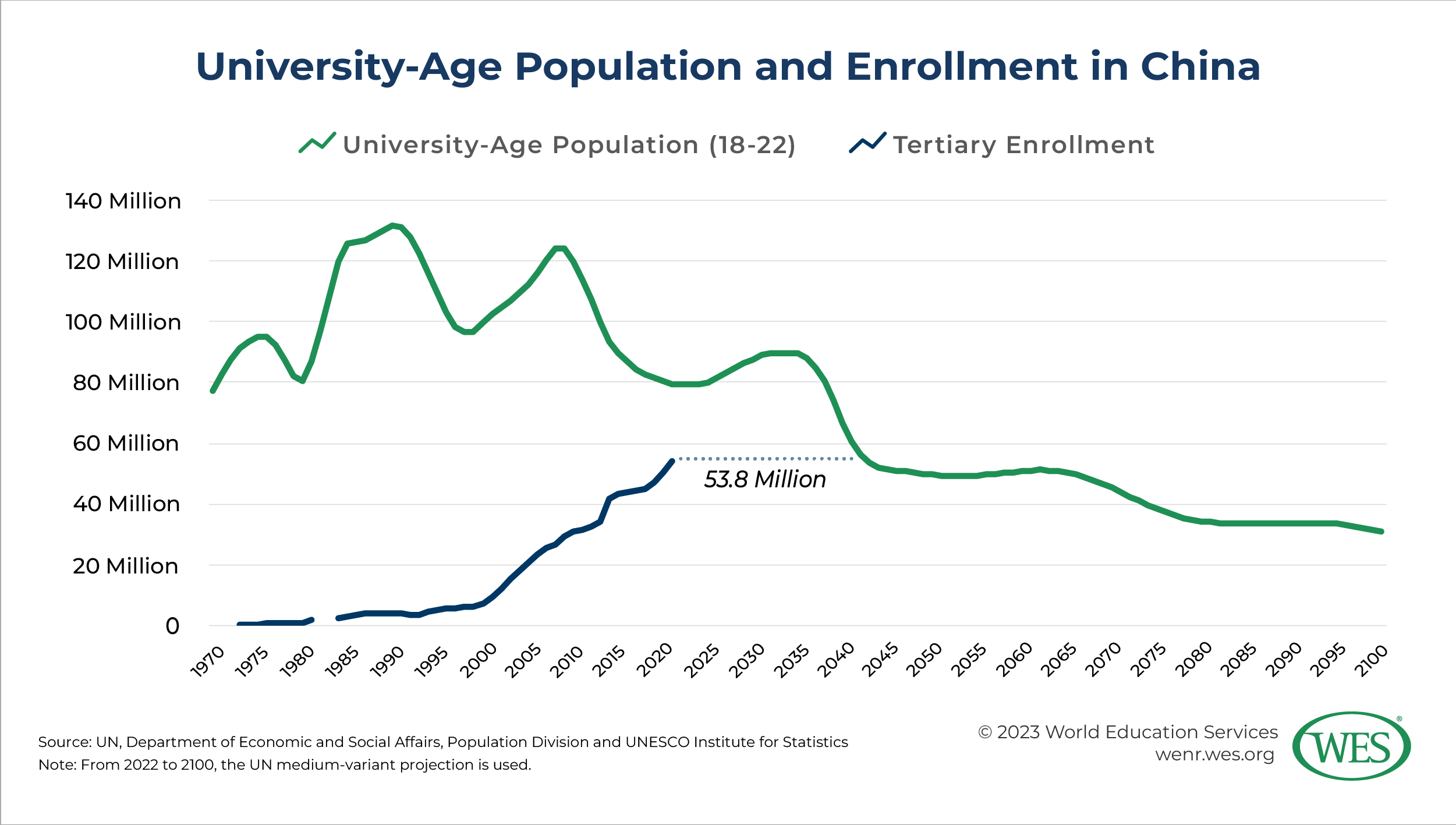

Rapid growth has also characterized Chinese higher education over the past two decades. To obtain the skills needed by the country’s expanding roster of advanced industries, more and more Chinese young people have opted to pursue a university education. Between 2001 and 2021, China’s tertiary gross enrollment ratio (GER) skyrocketed, growing from 9.8 percent [9] to 63.6 percent. Over the same period, tertiary enrollment expanded at an almost inconceivable pace, rising from 9.4 million [10] to 53.8 million, the equivalent of adding more than double the entire U.S. tertiary student population in just two decades.

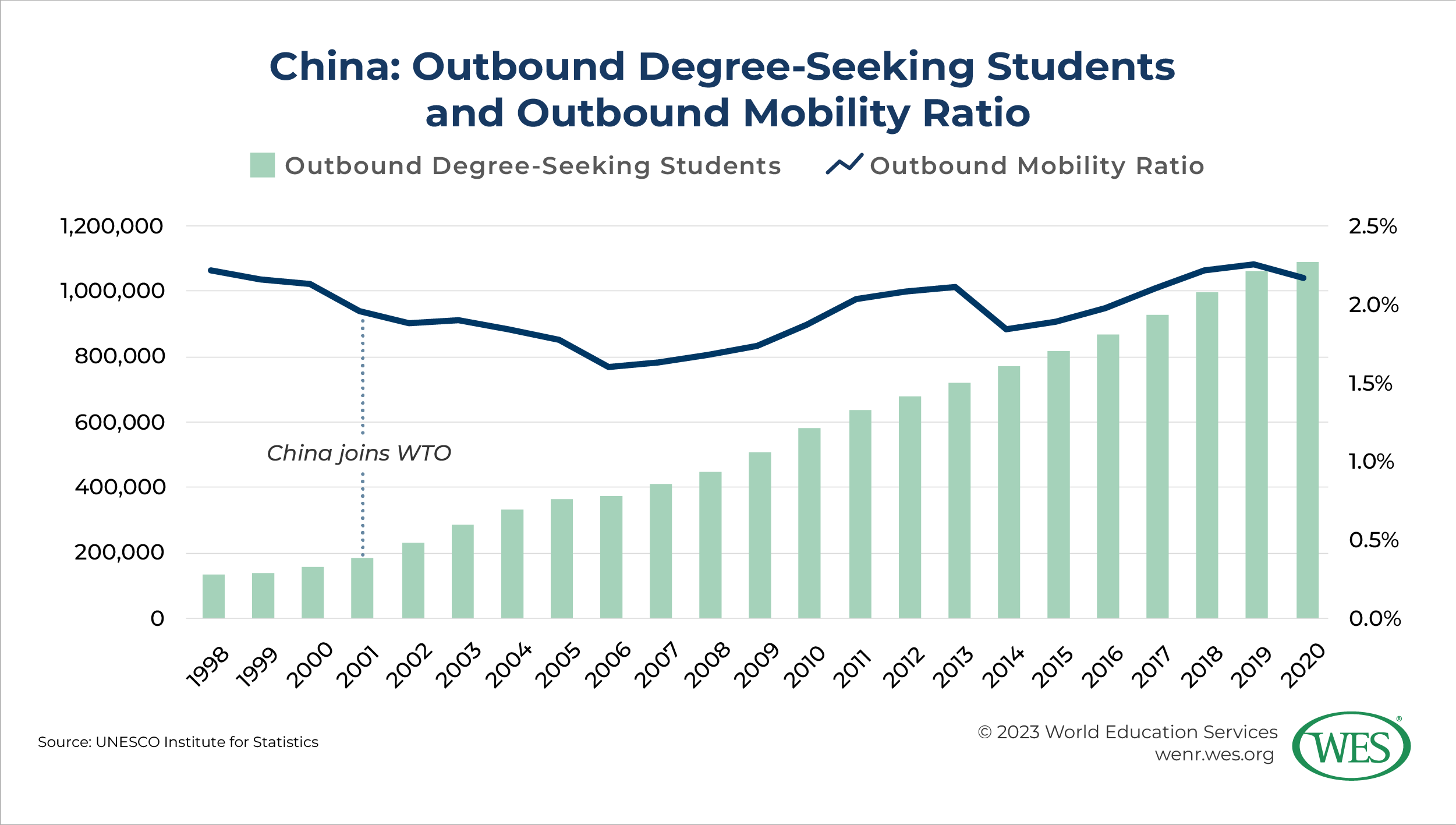

While most of these new university students enrolled in institutions in China, many looked overseas. Although China’s outbound mobility ratio has long hovered around 2 percent [12], the rising tide of tertiary enrollments also lifted outbound mobility. Between 2001 and 2020, the number of Chinese outbound degree-seeking students grew by nearly 500 percent [13], from under 200,000 to nearly 1.1 million.

These figures combine to paint a neat picture of Chinese international student mobility in the twenty-first century. With the country’s roaring economy opening a path to upward mobility for university graduates, ever growing numbers of China’s massive youth population are electing to pursue a university education. Although most choose institutions in China, the overall rise in university enrollment is lifting international enrollment figures as well.

But with each passing year, this neat picture grows less and less representative of current realities. As demographic, economic, and educational realities shift, the direction of Chinese international student mobility grows progressively more complex and its future increasingly hard to predict.

Demographic Contraction Outpacing Enrollment Expansion

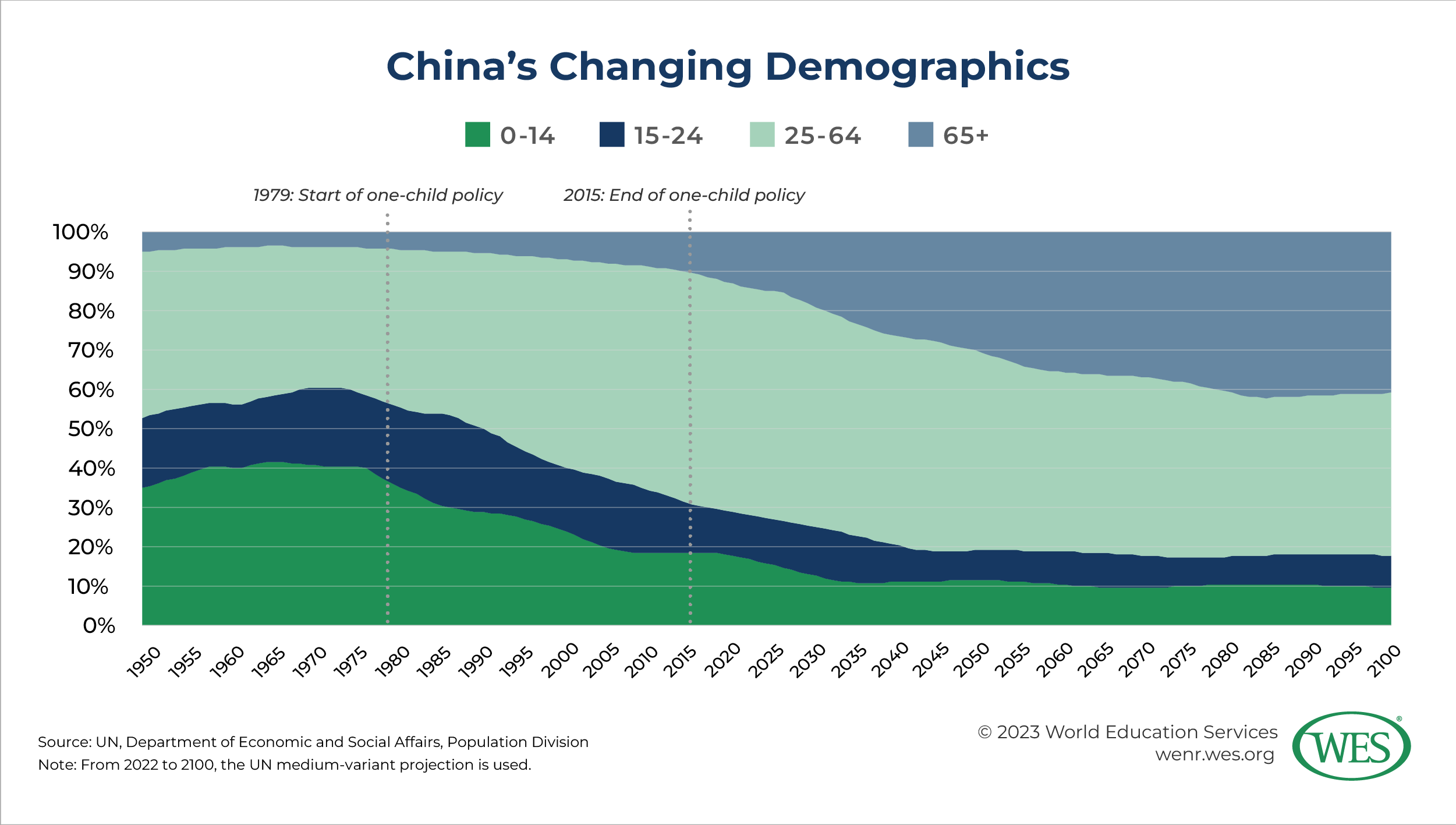

As noted in Part I [2], China’s population is shrinking. Although the government ended [15] its one-child policy in 2016, the nation’s fertility rate (1.18) remains well below the level needed for a stable population (2.1). The UN projects [16] that China’s population will decline from around 1.4 billion today to 1.3 billion in 2050 to less than 800 million in 2100.

China’s population is also aging rapidly. In 2022, 13.7 percent of the population was 65 or older. By 2050, that percentage is expected to grow to 30.1 percent. Over the same period, the percentage of the population between the ages of 15 and 24 is expected to fall from 11.3 percent to 7.6 percent.

These demographic trends will naturally narrow the pool of potential university students. While regional comparisons suggest that China’s tertiary GER still has room to rise—South Korea’s tertiary GER reached 88.2 percent in 2019—it won’t be long before demographic contraction begins to outpace tertiary enrollment growth. After prospectively rising to 89.9 million in 2034 (from 79.4 million in 2022), China’s university-age population is expected to contract rapidly. In less than 10 years, trends suggest, the number of people between the ages of 18 and 22 will decline by 40 percent, falling to 53.3 million in 2043. By that time, the number of potential Chinese university students will be less than the number of Chinese tertiary students today (53.8 million). That pool will continue to shrink gradually in the decades to come.

Declining Economic Growth and Rising Youth Unemployment

China’s rising tertiary enrollment numbers, both domestic and international, have long been tied to the country’s growing economy. But unfavorable headwinds could hamper China’s economic performance—and diminish the value of a university degree.

In the short term, the pandemic and related containment measures have had a disruptive impact on China’s economy. After decades of strong growth, the outbreak of COVID-19 caused China’s economic growth to slow sharply. In 2020, China’s gross domestic product (GDP) grew at just 2.2 percent [19], the slowest in nearly half a century. Although it rebounded to 8.1 percent in 2021, growth slowed to 3.0 percent [20] in 2022. While a slight uptick [21] in business activity followed the government’s decision to drop its zero-COVID policies in late 2022, the most recent economic data suggest that growth will again be sluggish [22] this year.

But China’s economic struggles extend beyond the disruptions caused by the pandemic. Many experts believe that China is entering an era of much slower economic growth as a result of unfavorable demographics, rising debt, a real estate downturn, and other long-term challenges. The Lowry Institute, a respected Australian international policy think tank, expects [23] Chinese GDP growth to average between 2 percent and 3 percent until 2050—a sharp departure from the more than 10 percent it averaged between 2000 and 2020. Slowing growth has even prompted some experts to retract their prediction [24] that China would become the world’s largest economy by the end of this decade.

Even more troubling, for China’s higher education system, is the country’s high and rising youth unemployment rate. Since the early 2000s, the jobless rate [25] among young Chinese has grown steadily alongside China’s expanding economy. In April 2023, the youth unemployment rate hit a record high, with more than one in five (20.4 percent [26]) Chinese youth between ages 16 and 24 unemployed.

China’s Interconnected Labor and Education Markets

In the coming months, 11.6 million Chinese university graduates [27], another record high number, will enter this already strained labor market. They hold dim views of their job prospects. A recent survey from Zhaopin, a Chinese recruitment company, found that two-thirds [28] of this year’s prospective graduates are worried about finding jobs after they receive their degrees.

Many observers attribute the country’s high rate of youth unemployment to a misalignment between its higher education system and the needs of its employers. A recent analysis [29] from Goldman Sachs identified “mismatches between skillset graduates acquired from their higher education and skillset required by employers in industry with booming labor demand” as some of the primary factors contributing to the country’s high youth jobless rates.

Chinese government officials seem to agree. Earlier this year, they announced a major revamping [30] of university disciplines aimed at better aligning the higher education system with the nation’s economic needs and policy priorities. Under this initiative, which will impact about 20 percent of all university subjects by 2025, the government plans to add around 10,000 science and technology programs—with a focus [31] on priority industries such as semiconductors, computing, and energy—to the nation’s higher education system. The revamping will also eliminate subjects identified by provincial education authorities as not contributing to national priorities.

Chinese education authorities have also moved to address what they perceive to be a glut of university graduates. In recent years, they have worked to shift the emphasis of the education system away from academic study toward non-academic training and to promote alternatives to a university degree for China’s youth.

In early 2019, the Chinese government published its National Vocational Education Reform Implementation Plan [32], earmarking 100 billion yuan [33] in funding to increase the percentage of students enrolled in vocational secondary schools from 40 percent to 50 percent. China is also piloting a ‘1+X’ system [34] of study and training at certain universities and vocational colleges, which would increase the vocational focus of university programs and allow students to graduate with both an academic degree and a vocational certificate.

Although an academic university-level education remains a deeply embedded cultural value in China, officials are taking steps to burnish the reputation of vocational training. For example, China’s Ministry of Education declared that vocational education shares the same elevated status as academic education, in a 2022 revision [35] to the country’s Vocational Education Law. The Chinese government has also taken steps to, in the words of Zhou Zhong, an associate professor at Tsinghua University’s Institute of Education, relieve the “pressure-cooker environment [36] of schooling” and “change China’s cultural veneration for top-flight education above all other options.” For example, China recently passed a law to reduce the “twin pressures [37]” of excessive homework and after-school tutoring.

In addition, Chinese authorities are rumored to have eased the zhongkao general high school entrance examination’s default 50 percent failure rate. The zhongkao is an important milestone in a student’s education. Traditionally, students scoring below the 50th percentile on the examination proceed to vocational high schools, while those scoring above it move to general high schools, in preparation for a university education. According to Zhong, authorities made the change to “blur the distinction” between academic and vocational education.

The recent announcement of the first tuition fee hikes [38]—of up to 54 percent at some universities—in two decades also signals the Chinese government’s changing attitude toward university education. Chinese education administrators have long prioritized affordability as a primary means of expanding access to a key public good: a university education. Although administrators say the price hikes are necessary to shore up pandemic-battered public budgets, the willingness to approve these increases seems to indicate a diminished standing of expanding higher education access among China’s policy goals.

Chinese authorities apparently hope these moves will dissuade some students from pursuing a university education and eventually reduce the number of graduates entering the country’s overwhelmed labor market. But some evidence suggests high youth unemployment may actually raise university enrollment levels.

In 2023, for the first time in China’s history, more students are expected to graduate [27] from the country’s universities with a master’s or doctorate than with an undergraduate degree. Some experts attribute this development to the country’s weak labor market. With post-study employment prospects dim, more students are choosing to extend their education and to delay their entry into that market. Instead of searching fruitlessly for a job after completing their undergraduate studies, they increasingly are pursuing a graduate university path.

The weak labor market may also be driving growing graduate enrollment abroad. Although Chinese enrollment in U.S. undergraduate programs declined by 12.8 percent [39] between 2020 and 2021, and between 2021 and 2022, enrollment in graduate programs rose by 3.6 percent [39].

Youth Unemployment and Outbound Mobility

As these graduate enrollment trends suggest, job prospects at home strongly influence outbound student mobility from China. A recent survey [40] from BONARD, a market intelligence firm for the international education sector, found that gaining an advantage in the Chinese labor market was the primary goal for studying abroad for around a third of prospective Chinese international students (31 percent) and their parents (34 percent), second only to expanding opportunities for further study (33 percent of students and 35 percent of parents).

But experts are torn [36] on exactly how China’s weak labor market will affect outbound mobility. Some believe that high unemployment could dissuade students and their families from the goal of studying abroad—as employment opportunities become scarcer and scarcer, an overseas education no longer seems worth the large investment required.

Under these conditions, the dramatic improvements [41] made by China to some of its higher education institutions could tip the scales even further against international study. Since the 1990s, China’s government has invested billions to develop and improve a handful of elite universities. Excellence initiatives, such as Project 211, Project 985, and the Double First Class initiative, have strengthened educational quality, boosted research capacity, and improved international competitiveness at a select number of universities.

Similar initiatives continue to this day. While China’s government has moved in recent years to promote vocational education and training, it has also doubled down on its commitment to top-tier research universities. In a recent session of the Politburo, Chinese president Xi Jinping identified [42] the creation of world-class universities that aim at “the frontiers of the world’s science and technology and major national strategic needs” as one of the nation’s priorities. To that end, despite tightening public spending in most sectors, the Chinese government is increasing its spending [43] on science and technology. Experts expect support for elite higher education institutions and critical research to continue in the years to come, as the government looks to nurture innovation and boost productivity to compensate for the country’s shrinking labor force and growing elderly population.

These investments have already paid off. For the first time, China’s universities (338) outnumbered those of the U.S. (280) on the 2022-2023 Best Global Universities Rankings [44] from U.S. News & World Report.1 [45] These universities are producing important research. According to a recent report [46], China’s research leads the world in 37 out of 44 critical and emerging technologies.

These improvements have caught the attention of employers in China. Recent research suggests [47] that a U.S. degree no longer gives most Chinese international students an advantage in the Chinese job market.

International comparisons suggest that these developments could have a dramatic impact on China’s outbound student mobility. In South Korea, similar demographic and labor market dynamics [48] have driven a gradual but steady decline in outbound student mobility. In 2020, the number of South Korean international students was 15.2 percent [13] lower than its peak in 2009.

Despite these dynamics, other experts believe that China’s high unemployment rates could encourage students to study overseas. They contend that Chinese youth still view international study, especially at top institutions and programs, as an important means of distinguishing themselves in an increasingly competitive job market.

A weak labor market could even reshape the typical Chinese international student profile. Traditionally, young Chinese nationals have viewed studying abroad as a fulfilling, but ultimately temporary, life experience. According to the BONARD survey mentioned above, just 12 percent of prospective Chinese international students identified finding a job overseas as their primary goal when studying abroad; even fewer (8 percent) selected immigration as their main goal.2 [49] After obtaining an international degree, most Chinese students head home to find work and settle into their adult life. According to China’s Ministry of Education, more than 80 percent [50] of Chinese students who studied abroad between 2012 and 2022 returned to China.

But if the job market becomes weak enough, growing numbers of Chinese youth may opt to pursue an overseas education not to increase their chances of landing a job at home, but to secure employment, and perhaps even long-term residence, abroad.

Global Competition

It is still too early to know what impact high unemployment rates will have on outbound mobility. However, if overseas employment does become a more important driver of Chinese international student mobility, post-graduation work rights and permanent immigration pathways will become a more important factor in the application and enrollment decisions of prospective Chinese international students.

While the U.S. offers international students comparatively generous [51] post-graduation work rights, domestic pathways to permanent residency [52] are limited. More welcoming visa regulations are among the many possible measures that countries around the world are eyeing in a bid to attract more Chinese international students.

The next article in this series will examine the international scramble for Chinese students. Although the U.S. remains at the top of the list of choices, other countries—both traditional and emerging international education hot spots—have grown increasingly popular in recent years. Looking at the global recruitment landscape is essential for a thorough understanding of the future of Chinese international student mobility and the U.S.

1. [53] International branch campuses (IBCs) may also offer Chinese students an in-country alternative to overseas study, allowing Chinese students to obtain an international degree without many of the expenses and difficulties of traveling overseas. A China Institute of College Admission Counseling (China ICAC) survey [54] of 121 high school guidance counselors in China found that “71 percent of counselors reported that they saw an increase in the number of students and parents inquiring about global campuses in China.” As of March 2023, China hosted 47 IBCs [55], the most in the world. Sixteen of China’s IBCs come from the U.S.

2. [56] Their parents were even less interested in a long-term stay abroad. Just 10 percent of parents indicated that the goal they had for their children for studying abroad was to have a chance at a job overseas; only 5 percent selected immigrating overseas.