International student mobility in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) is surging. The latest available UNESCO statistics show that the number of students from the region enrolled in degree programs outside their own countries increased by nearly 170 percent over the past two decades, from 163,653 in 1998 to 441,537 in 2021 [2]. Only around 20 percent of these students are enrolled in other African countries, while the vast majority study in countries not on the African continent, primarily in Europe and the United States as well as in other parts of the world, including China and the Middle East.

Given that many African students use their international education as a springboard for emigration to wealthier countries in the Global North, current mobility patterns tend to sap African societies of human capital, thereby hampering the development of African economies. To be clear: The impact of the outflow of students and skilled talent varies by country and is not entirely negative: It has been argued that mobility from developing to industrialized countries results in “brain circulation”—the transfer of skills and knowledge—if students return to their countries of origin. And that the remittances sent by émigrés have a positive impact on local economies [3] back home. Diaspora networks may facilitate international trade [4], foreign direct investment, academic cooperation, and other benefits.

However, there’s little doubt that the largely one-directional south-north flow of migrants and students results in considerable “brain drain,” or human capital flight, in many African countries. It’s a fact that large numbers of international students emigrate permanently. As the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) notes in “International Migration Outlook 2022 [5],” its latest international migration report, former “international students are an important feeder for labour migration in many countries. Transition from study permits accounted for a large share of total admissions for work in 2019, especially in France (52 percent), Italy (46 percent), and Japan (37 percent). In the United States, former study (F-1) permit holders accounted for 57 percent of temporary high-skilled (H-1B) permit recipients.”

This development comes amid an extreme scarcity of human capital in SSA, where the tertiary gross enrollment ratio stood at merely 10 percent [6] in 2020 (compared with an average of 40 percent [7] globally). SSA is one of the world regions most affected [8] by human capital flight, alongside small island nations in the Pacific and the Caribbean. In Nigeria, for example, outmigration has become so prevalent that seven out of ten residents would leave the country if given the opportunity, according to recent surveys [9]. Former president of South Africa Thabo Mbeki has called Africa’s brain drain “frightening,” and he estimated that more African scientists and engineers live and work in the U.S. and the United Kingdom than anywhere else in the world [10].

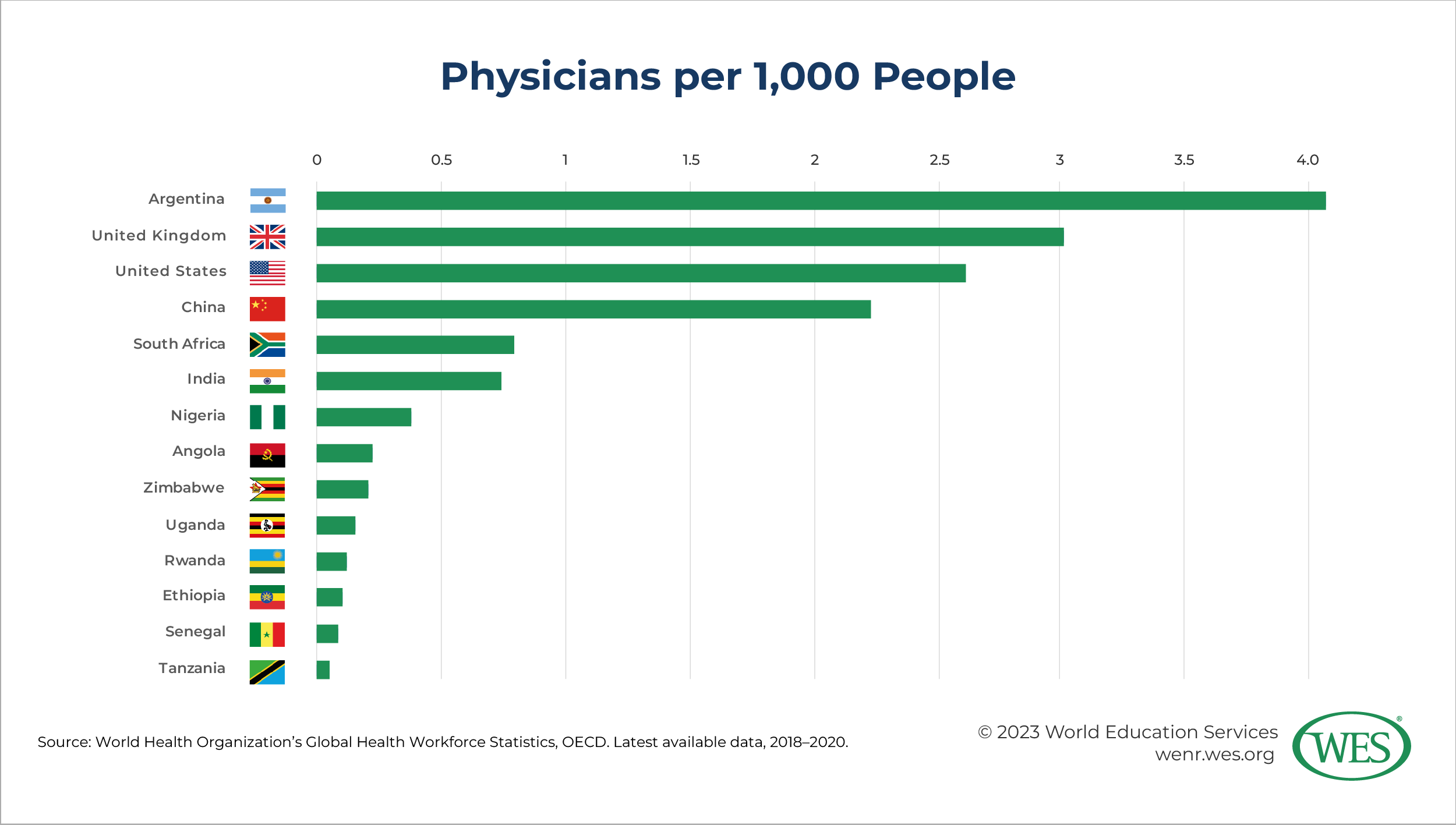

This trend deprives countries of urgently needed professionals in critical areas like medical care. As the president of the Nigerian Association of Resident Doctors told CNN, “If nothing is done to reduce the rate at which doctors, medical professionals, and other health care workers are leaving the shores of this country … I’m not sure whether any doctor will be left [11]” in Nigeria in a matter of years. To counteract these developments, the government of Zimbabwe recently announced it would criminalize the recruitment of health workers from overseas after losing 4,000 doctors and nurses to emigration over the past two years [12]. SSA already has the lowest number of doctors per citizen in the world [13].

Calls for more science and education “in Africa, by Africans, and for Africans” are consequently common among African academics. Scholars of the African Academy of Sciences, for instance, recently noted that it’s “critical that Africa … nourishes the potential of its intelligentsia in Africa. The post-colonial reality … has been that the most qualified students and early career researchers seek advanced training in the Global North, in many cases immigrating there. While this enriches the receiving countries, it drains the originating countries of their best talent. … ‘Losing’ these students and researchers to countries in the Global North represents the loss of not just talent but also economic generation, intellectual property, mentorship, and modeling for future generations [15].”

Against this backdrop, several initiatives have been launched to boost student mobility within Africa. As early as 1981, the Arusha Convention [16] sought to improve the mutual recognition of academic qualifications to allow for greater regional mobility. The 2004 Accra declaration [17], likewise, promoted greater cross-border access to higher education to increase “academic mobility within Africa itself.” More recently, the EU-funded “Intra-Africa Academic Mobility Scheme” supported student and staff mobility with the objective to strengthen “human capital development in Africa” and establish “mechanisms to enhance mobility flows [18]” on the continent. Another project, the “Harmonization of African Higher Education, Quality Assurance and Accreditation” initiative (HAQAA), currently seeks to develop a common African Credit Transfer System, akin to the European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS), to “support mobility and transferability of knowledge and learning across African regions and institutions [19].”

This article takes stock of academic mobility in SSA and analyzes current patterns and trends in African student flows, both externally and within the African continent. It also outlines the challenges and obstacles to intraregional mobility, describes the current political initiatives to boost it, and discusses how mobility in Africa might evolve in the future.

It should be emphasized that data on student mobility in Africa is limited and hard to obtain. Many African countries don’t systematically collect this type of data, nor do they publish it. The UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) provides the largest data repository for global student flows and its data set is the only one of its kind that allows for direct comparisons according to one standard definition of an international student. The institute’s latest complete statistics are from 2021 and were used as the main source of analysis for this article. One limitation of the data is that it only includes tertiary degree-seeking students and does not factor in visiting students on short-term exchanges or those enrolled in vocational or other programs. Other sources may sometimes report higher numbers of international students because of this fact.

The Overall Picture: Main Study Destinations

From a global perspective, the number of international students from the SSA region is still relatively small when compared with regions like Asia or Europe. Only 6.9 percent (441,500 students) of the 6.4 million mobile students enrolled in degree programs in other countries worldwide in 2021 came from SSA countries, according to UIS data. China and India alone accounted for far more of the world’s international students each. That said, the frequency with which SSA students head abroad is above average. The outbound mobility ratio for the region is more than twice as high as for East Asia, South Asia, or North America. Given the educational capacity constraints in SSA, there are only some 9.6 million tertiary students in the entire region combined, compared with 57 million tertiary students in China and 40.5 million in India. But approximately 4.6 percent of SSA students enroll in other countries compared with merely 1.9 and 1.3 percent of tertiary students in the two mega-countries, respectively.1 [20]

Destination-wise, international student flows in SSA still mainly follow a south-north trajectory, despite growing diversification in recent years. As discussed in greater detail below, only 20 percent of mobile students stay within the region. The largest share of degree-seeking students—41 percent in 2021—were instead enrolled at universities in Europe, with France the single most popular destination country (14 percent of all enrollments).

France’s position as a top destination is attributable largely to colonial ties and the shared French language in former French colonies on the continent. More than 90 percent of SSA students in France come from French-speaking nations, primarily Senegal, Côte d’Ivoire, Cameroon, Gabon, and Congo. A majority of students are enrolled at the undergraduate level [21], where the availability of English-taught programs is limited. The French government also incentivizes the inflow of African students with scholarships. However, it remains to be seen how mobility will develop long-term amid the waning of French influence and the ouster of several pro-French governments in Francophone Africa in recent years.

Other major destination countries in Europe are the U.K. and Germany. Portugal also hosts many students (16,900), almost entirely from its former African colonies Cabo Verde, Guinea-Bissau, Angola, and Mozambique. The U.S. is another popular destination for mobile students from SSA, accounting for about 9 percent of all enrollments in 2021 (38,500 students). Unsurprisingly, U.S.-bound students come predominantly from English-speaking countries. Nigeria, by far the largest sending country overall in all of Africa, is also the main source country for U.S. universities, accounting for 32 percent of U.S.-bound students, followed by Ghana and Kenya. The number of outbound Nigerian students has risen sharpy in recent years, with enrollments in the U.S. almost doubling over the past decade. The situation is similar in Canada, where the number of Nigerian students has quadrupled since 2011. The country is now a major host country for students from SSA, with 25,000 enrollments.

A newer trend is a greater diversification of mobility flows toward “nontraditional” host countries like Türkiye or Saudi Arabia. Türkiye has made major efforts in recent years to become an international education hub, including the provision of 14,000 scholarships for African students [22]. The number of students from SSA enrolled at Turkish universities rose from a few hundred in the mid-2000s to 22,300 in 2021, with Somalia and Nigeria being the top sending countries, per UIS. Saudi Arabia, likewise, invests heavily in scholarship [23] programs [24] for Africans and hosted 9,600 students from various SSA countries in 2022.

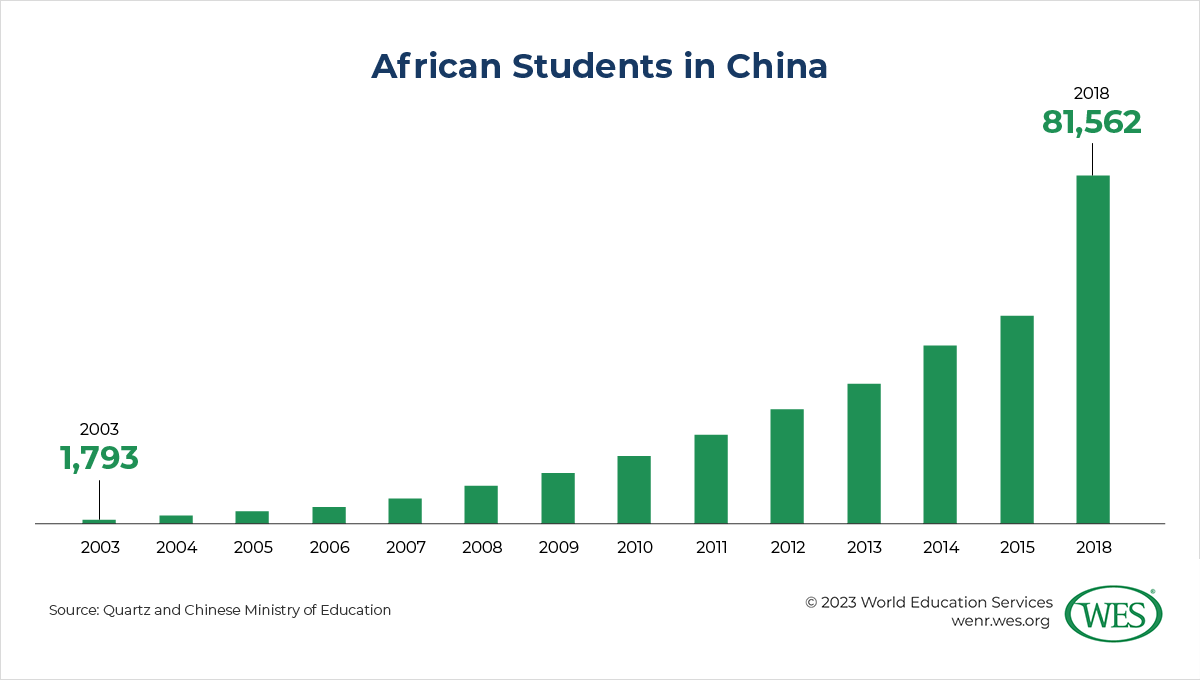

Notably, China in recent years has become a major study destination for Africans as well. Pre-pandemic data released by the Chinese government reflects that the number of African students there has spiked greatly, reaching more than 80,000 in 2018 [25]. This trend coincides with China’s emergence as Africa’s largest trading partner and the country’s growing engagement on the continent, including in education [26]. However, the Chinese data cannot be directly compared with UIS statistics, which count only tertiary degree-seeking students and don’t report numbers for China. The Chinese data, by contrast, also include students in high school and in various short-term vocational training programs, some of which last just a few days or weeks [27]. Russia is another country intent on expanding its influence in Africa through education-related cooperation. The Russian government seeks to raise the number of African students in Russia to 40,000 by 2024 and has greatly ramped up scholarship funding to achieve this objective [28].

Intraregional Mobility in SSA

As we’ve seen, international students from SSA enroll primarily in wealthier countries with more developed education systems, such as former colonial powers, top Western study destinations like the U.S., and as of recently, China. While the total number of African mobile students has grown rapidly, UIS statistics show that the share of mobile students from SSA who enroll in another country within the region has decreased over time, from more than 35 percent in 2004 to 20 percent in 2021, while their enrollments in other world regions rose dramatically. For the most part, African student mobility remains characterized by what has been called “vertical north-south internationalization” and “look north” attitudes among students, universities, and policymakers [30]. Consider that almost 90 percent of mobile students from top-sending Nigeria and Cameroon are currently enrolled outside Africa.

Even within Africa, mobility patterns follow a somewhat similar trajectory: The largest host country by far of students from the SSA region, South Africa, is a regional economic hub—the second-largest economy after Nigeria and the most developed country in SSA after the small island nations of Mauritius and Seychelles (as measured by the UN’s Human Development Index [31]). South Africa has one of the most developed and extensive education systems on the continent, with the largest number of internationally ranked research universities, offering a broad variety of academic programs.

South Africa hosts about 32 percent of all mobile degree-seeking students who stay within SSA, making it the third most popular destination among students from the region overall, after France and the U.S. After the end of the apartheid regime in 1994, South Africa swiftly emerged as the main international study destination in the region. The number of SSA students in the country grew fourfold between 1999 and 2011, when it peaked at 61,400 students. Since then, however, that number has dropped substantially, to 28,424 students in 2021—a development that has been attributed to factors like anti-immigrant violence [32], widespread student protests [33], and underfunding of universities in a rapidly expanding education system, as well as a lack of affordable student housing [34] and of post-study work opportunities in South Africa’s faltering economy in recent years [35]. The country currently suffers from a sky-high youth unemployment rate of 45 percent [36]. As in most countries, student mobility was severely disrupted during the COVID-19 crisis, and it remains to be seen how international enrollments will recover in the coming years.

Most students in South Africa come from neighboring countries. Almost 10,000 from Zimbabwe alone were studying in the country in 2021, as well as thousands from Lesotho, Namibia, and Eswatini. Other major source countries were the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Nigeria: 2,770 and 2,521 students respectively. Most of the mobile students are enrolled in undergraduate programs [37], although growth rates in recent years were highest in graduate programs [38], which are scarcer and less accessible in many neighboring countries.

Factors that make South Africa an attractive destination for students from the region include geographic proximity and low tuition compared to those of Western destinations [39], “the presence of several South African HEIs in major international university rankings, a well-established HE sector offering internationally recognized qualifications, the use of English as the main medium of instruction, and relatively low costs of living [40].” Notably, South Africa is a regional leader in distance education, and substantial numbers of international students are enrolled there remotely. The University of South Africa (Unisa), a distance education provider that has the country’s highest university enrollment and is one of the world’s mega-universities, hosts the nation’s largest share of international students, followed by internationally top-ranked institutions like the University of Cape Town and the University of Pretoria [37]. Apart from tertiary education, substantial numbers of international students attend technical and vocational training programs.

It’s important to note that integration and harmonization measures within the framework of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) are an engine of internationalization and student mobility within the region. Most of the 16 member states [41], including South Africa, have pledged to ease visa requirements for citizens of other SADC countries, while universities are expected to reserve at least 5 percent of their seats for students from other SADC nations [42]. As discussed further below, implementation of visa-free movement is still patchy and doesn’t apply to student visas, but the SADC has brought significant improvements. Students from SADC countries pay the same tuition fees as local students in South Africa, for example. Beyond that, the SADC is working on implementing a regional qualifications framework to facilitate comparability and recognition of academic qualifications, including a common credit transfer system and harmonized quality assurance standards [43]. Also under consideration is adoption of a common regional student visa for the entire SADC bloc [44].

Aside from South Africa, the few SSA countries with more sizeable international student populations include Senegal, Kenya, and Ghana. Senegal hosts 16,000 students from various African countries drawn by its high-quality education system and the presence of specialized institutions like maritime training institutions, not found elsewhere in the region. Kenya, which hosted 6,828 students in 2019, according to the latest available UIS statistics, is an economic hub and magnet for regional labor migration attracting students from East Africa and beyond. Kenyan authorities seek to increase the country’s international students to 30,000, primarily by recruiting from the East Africa region [45]. But note that the UIS doesn’t provide inbound student data for Nigeria, Uganda, and other countries, making inflow difficult to compare among individual countries. According to Ugandan government statistics, that country hosted more international students than Kenya did—as many as 19,000 in 2018 [46]. A large share of these students came from Kenya and other neighboring countries, drawn by comparatively lower tuition fees [47].

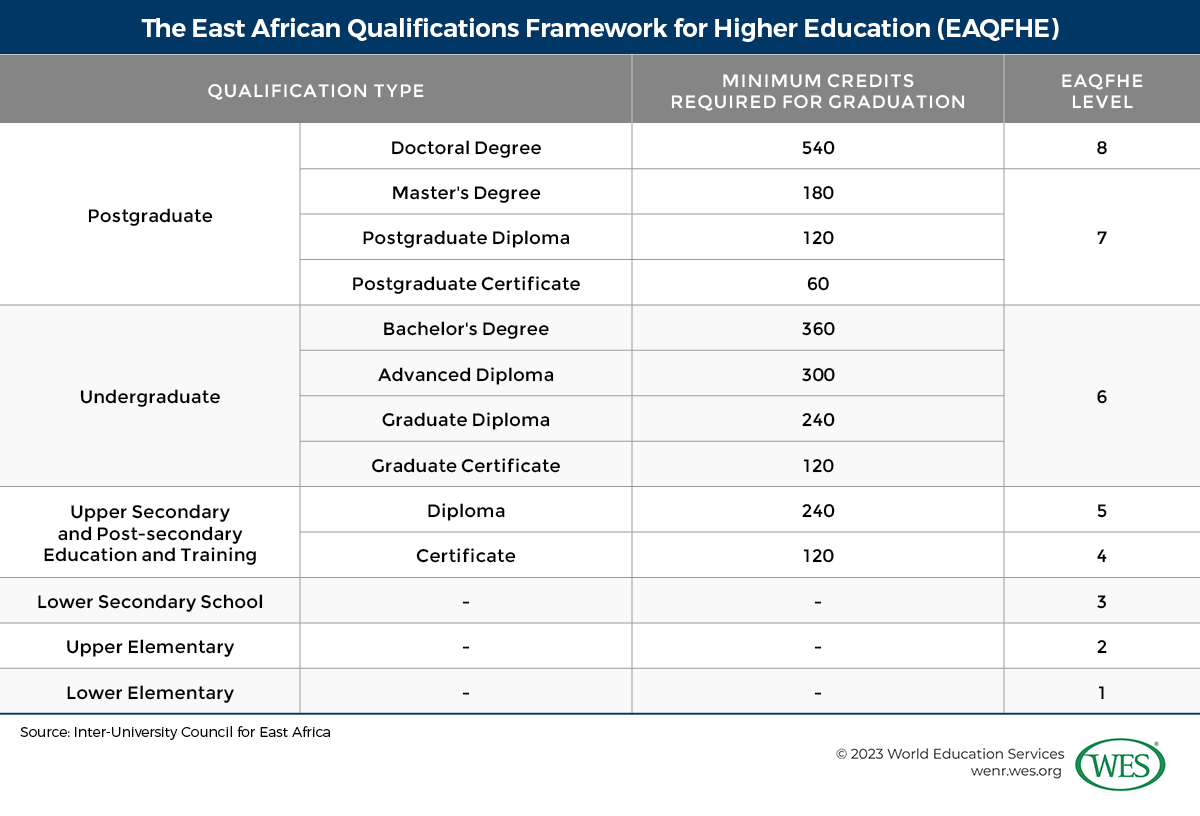

Student mobility within the East African Community (EAC), an intergovernmental organization and free trade area consisting of Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, South Sudan, Tanzania, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), and Uganda, is expected to increase further in the future. In 2017, the organization declared a Common Higher Education Area [48] with the goal of lowering barriers to academic mobility—a reform agenda similar to the one pursued by the SADC in Southern Africa. Steps that have been taken or initiated include lowering tuition for international students, establishing a regional credit transfer system, and implementing an East African Qualifications Framework to improve the comparability and recognition of academic qualifications [48].

Aside from these measures, research cooperation and scholarship programs have a direct impact. A recent World Bank–backed program called ACE II [49], for instance, has funded thousands of scholarships for graduate students and the creation of various research centers at universities in Eastern and Southern Africa [50]. In Rwanda, which hosts four of the new centers, the number of international students subsequently spiked. Minor as the total count may be, the number of students from other SSA nations in the small country of 13 million more than quadrupled within just six years, from 731 in 2015 to 3,860 in 2022.

Prospects for Greater Intraregional Mobility

The education systems of many sub-Saharan countries are under tremendous stress. Access to higher education in chronically underfunded and capacity-strained systems is extremely limited and remains a privilege of the few. Youth unemployment in the SSA region, where almost 60 percent of people are under the age of 25, stands at 12.4 percent [51], while the youth population is expected to double by 2050 [52]. In the current reality, education is often of little relevance to employment prospects [53]; university graduates frequently end up working in the informal sector [54]. Human capital development is paramount if African societies are to escape underdevelopment.

Against this backdrop, it’s unsurprising that so many African students leave the continent for education and training. The push and pull factors driving mobility on the continent are well known. They include, among others, access to higher education that is unobtainable or of better quality than at home, improvement of employment prospects, access to scholarships, and escape from political instability and conflict. At the same time, there are more study abroad opportunities available than ever as growing numbers of countries compete to attract international students and skilled talent worldwide. It would be naive to assume that these structural conditions and the current geography of student mobility will dissipate in the medium-term future. Most mobile African students who have the chance to do so will continue to study in the Western world and other countries with more developed economies, more advanced education systems, and better employment opportunities.

However, the integration initiatives of the SADC and the EAC demonstrate that intraregional student mobility is not a lost cause. The regional economic communities that have been established in different parts of Africa track European economic integration, followed by the establishment of a common higher education area, if in a more nascent phase. Intra-European student and staff mobility increased considerably after it became prioritized in the framework of the Bologna reforms. While the official goal that 20 percent of all graduates in the European Higher Education Area have some form of study abroad experience has not been realized [55], UIS statistics show that the number of Europeans studying in other European countries doubled between 1999 and 2021.

In Africa, as elsewhere, geographic proximity and lower costs of local education, coupled with a favorable regulatory environment, should incentivize regional mobility, particularly among less affluent students unable to afford an education in the Global North. The bulk of intraregional mobility in SSA—and in fact a sizable share of academic mobility worldwide—already occurs between neighboring countries. The shared use of English or French as languages of instruction in higher education in many African countries provides conducive structural conditions as well.

Barriers to the Free Movement of Students

One factor shown to improve prospects for greater mobility is easing of visa requirements. Several countries that seek to attract international students have adjusted their visa policies and eased requirements for post-study work or immigration. While parts of SSA have seen significant changes in this respect in recent years, traveling between or working and studying in other African countries remains comparatively difficult for many Africans. Despite the African Union (AU)’s goal of adopting a joint pan-African passport and creating a “borderless” Africa with seamless intracontinental migration [56], hurdles to the free movement of people persist. Currently, only three states—Benin, Seychelles, and the Gambia—allow visa-free entry for citizens of all other African countries. While some countries have relaxed their visa regulations in recent years, 47 percent of Africans still require pre-departure visas even for short-term stays in other African countries [57].

In contrast to the European Schengen area, “on which the AU effort was modeled, Africa is more accurately described as a continent with multiple overlapping subregions that allow varying degrees of free movement [58]”. However, even within regional communities, such as the EAC and the SADC, free mobility protocols aren’t always implemented consistently. As the Migration Policy Institute notes, some African states are hesitant to open their borders because they view migration as an economic and national security threat. [58] There are wide wealth disparities between some states and anti-immigrant sentiments make the unrestricted movement of people a political issue in some countries [59]. At any rate, not all free travel agreements apply to international students. In South Africa, for example, students from SADC countries need to apply for student visas, which involves proof of adequate funds and health insurance. There are reportedly steep bureaucratic hurdles [60] to obtain a post-study work permit to enter the already severely depressed South African labor market.

Funding and Scholarships

The cost of study is a critical factor in SSA—a region where tertiary education “has remained elitist, benefiting students mostly from the most affluent, well-connected families [61].” This holds especially true for international education, which is often exponentially more expensive. Unsurprisingly, then, access to scholarships is a major mobility driver—demonstrated perhaps most pointedly by the unprecedented spike in student outflow from Saudi Arabia after the country launched the King Abdullah Scholarship program, a mass-scale study abroad offering, in the 2000s. China’s rapid rise to popularity as a study destination for Africans, likewise, is largely scholarship fueled; by some accounts the country is now the largest funder of academic scholarships for Africans worldwide [62]. The EU’s Erasmus mobility program has helped to send hundreds of thousands of students abroad. As noted before, external funding through the ACE II project has facilitated intraregional mobility in SSA as well.

Countries like Egypt, Iran, Pakistan, and Vietnam in recent years have adopted funding strategies that seek to build human capital in critical areas by sending top students overseas while simultaneously trying to minimize brain drain. Mostly intended for graduate students and researchers, these scholarships are set up in ways that incentivize students to return home after graduation—either by making funding directly contingent on returning or by providing dedicated research grants or guaranteed employment for returnees [63]. In Indonesia, for example, recipients of government scholarships were required to return and work or incur a penalty twice the amount of the scholarship. A similar emphasis on recirculating talent could guide SSA initiatives aimed at boosting intraregional mobility. While mass-scale scholarship programs like Erasmus would be a tall order for SSA’s cash-strapped governments, extra-regional funding could help fill existing gaps if initiatives focus on strengthening academic exchange within the region rather than on recruiting students for the benefit of donor nations. The EU’s Intra-African Mobility Scheme [64] is an example of such a project.

“Virtual mobility” via online learning could also play an important role in expanding regionalized cross-border education and help make it more socially inclusive. Whether online education will retain its current momentum in the post-COVID era remains to be seen, but distance learning certainly has tremendous potential for widening access to higher education in Africa [65]. The distance education programs of Unisa and other universities already enable large numbers of immobile students to access a comparatively inexpensive international education from their homes.

The same applies to branch campuses and transnational academic programs in Africa. While the quality of education at branch campuses varies greatly, they can support capacity building and diversify local academic offerings if they offer curricula tailored to local needs and labor markets, as opposed to functioning as decoupled “education islands” that provide foreign education only for wealthy elites. In Mauritius, a full 43 percent of all tertiary students were registered with some type of foreign provider in 2016; the proportion was 30 percent in Botswana [66]. Although Africa still has comparatively fewer branch campuses compared to other world regions [67], French institutions have opened several campuses in Africa in recent years, and academic institutions from Egypt [68] and India [69] are increasingly establishing satellite campuses in SSA as well. The Somalia campus of Mount Kenya University and the Kampala International University in Tanzania are examples of regional players operating these types of campuses.

Structural Reforms and Integration of Education Systems

From a long-term perspective, structural reforms to harmonize and integrate education systems could perhaps have the greatest impact on intraregional mobility within Africa. Several of the current mobility projects in Africa are patterned after the Bologna Process with its internationalization imperative, and many of the initiatives are indeed funded and supported by the EU and European countries like France, Germany, and Sweden. Factors such as funding constraints, lesser governmental capacities, less economic integration, and greater disparities between African countries will make harmonization in SSA a much more difficult and lengthy process than in Europe. Many of the initiatives are embryonic and still under development. But they are investments bound to advance regional integration and mobility over time. Several of the reform efforts were pioneered in international organizations like the Conseil Africain et Malgache pour l’Enseignement Supérieur (CAMES)2 [70] and in regional blocs like the EAC and the SADC but are now slated to be expanded to the wider continent.

Qualifications Frameworks and Alignment of Quality Assurance Procedures

The influence of the Bologna reforms on African higher education is most evident in the restructuring of degree systems to match the European, and notably French, three-cycle degree system in Maghreb countries and the 19-member CAMES. While the outcomes of these reforms, which will make degree programs more uniform and comparable, are uneven in different countries, similar harmonization efforts are underway in other parts of the continent. Regional qualifications frameworks (RQFs) have been conceptualized in both the EAC and the SADC. The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) explored the establishment of an RQF as well but did not reach consensus on it.

In 2011, the SADC piloted the SADCQF [43] as a regional reference point for benchmarking and comparing qualifications. While this framework is still under development, the EAC in 2015 presented the East African Qualifications Framework for Higher Education (EAQFHE [71]). Member countries are currently expected to align their national frameworks to the regional framework. Below the regional level, growing numbers of African countries have started to develop their own national qualifications frameworks (NQFs)—a step that will assist in the development of QFs at the regional and continental levels [72]. Most of these frameworks span eight to ten levels of qualifications, from basic to doctoral education, as is customary worldwide.

Taking the concept to the continental level, the AU in 2019 launched the African Continental Qualifications Framework (ACQF) to link “regional qualifications and national qualifications frameworks to facilitate regional integration and mobility [74].” The proposed framework has 10 level descriptors but is still subject to modifications as member states assess the feasibility of the framework in the coming years. It will certainly be much more difficult to implement than RQFs, considering that only 19 out of 54 African countries had operational NQFs in place in 2021 [74].

Both RQFs and the ACQF are expected to be underpinned by harmonized quality assurance procedures to ensure that academic qualifications conform to comparable minimum standards and are relevant to labor market needs. Regionally, this process is steered by the East African Higher Education Quality Assurance Network (EAQAN [75]) in the EAC and the Southern African Quality Assurance Network (SAQAN [76]). At the continental level, QA harmonization is expected to be guided by the Pan-African Quality Assurance and Accreditation Agency (PAQAA). The creation of this agency is part of the latest round of the Harmonization of African Higher Education Quality Assurance and Accreditation initiative (HAQAA3 [77]), launched in the summer of 2023 [78] and currently led by the Association of African Universities (AAU), the Research Association OBREAL Global, the German Academic Exchange Service, and the European Association for Quality Assurance in Higher Education.

It should be noted that the new regional and continental QA bodies rely on the voluntary cooperation of universities and national governments for the implementation of quality standards. Their mandate is advisory in nature and focuses on training, consulting, and information sharing on best practices in QA. The establishment of external accreditation agencies or compulsory QA systems above the national level appears unlikely at this point. In general, establishment of more robust QA mechanisms still faces several challenges, including resistance by universities and governments, lack of expertise and qualified personnel, and overlapping responsibilities of different QA bodies in some countries. [79]

Common Academic Credit Systems

Another reform relevant to intraregional mobility is development of shared academic credit systems akin to the European ECTS. The EAC in 2015 introduced the EACAT (East African Credit Accumulation and Transfer), expected to be operationalized by 2025 [80], while the SADC developed the equivalent SADC CATS (Credit Accumulation and Transfer System). Both systems are aligned with and based on the British CATS credit system, which defines one year of full-time study as 120 credits. Once implemented, the new systems will allow for the direct transferability of academic coursework from one education system to the next without conversions. They will make academic qualifications more portable, as well as ease the recognition of prior learning. The HAQAA initiative seeks to replicate this model continent-wide with the African Credit and Transfer System (ACTS). The new system is currently piloted in select degree programs by 100 universities across Africa [19].

Verification and Authentication Procedures

Verifying the authenticity of foreign academic credentials is a key aspect of international admissions. The AU’s African Qualifications Verification Network (AQVN [81]), formed in 2016, aims to establish trustworthy linkages between universities and regulatory bodies to facilitate information sharing on academic qualifications. In addition to verification of credentials, the network aims to provide information on the nature of qualifications and the accreditation status of institutions to flag diploma mills and other illegitimate providers. As such, it fulfills a function similar to that of Europe’s ENIC-NARIC Networks and the European Diploma Supplement. It is a valuable service in an environment where information on other education systems is limited and fraudulent credentials and academic corruption are rife.

Whither Intraregional Mobility?

The harmonization of education systems in SSA will create structural conditions conducive to increased intraregional student and labor mobility. But this alignment needs to be understood as a long-term process that faces numerous hurdles. Compared with Europe, Africa is fragmented, with markedly lower levels of economic integration, trade, and overall mobility between countries. In the words of Marie Eglantine Juru, AAU project officer for higher education, developing an African Qualifications Framework alone will likely take several years, since it involves “aligning various educational systems, standards, and practices across African countries” and “sustained commitment, financial resources, and political support from African governments, educational institutions, and higher-education-related regional organizations [82].”

Even within the smaller regional communities, harmonization isn’t a linear process. EAC countries like Kenya and Burundi, for example, have education systems that are difficult to align because they are structured very differently. Other obstacles include regulatory diffusion, with different parts of education systems “administratively located in different institutions, making implementation of a comprehensive RQF rather challenging, a 2021 AU feasibility report notes. For example, while “university education is managed by the Inter-University Council of East Africa, TVET education is handled by the educational department of the EAC based in Arusha [74]. Adding to such complexities, some countries are part of different and overlapping regional communities (Tanzania, for instance, is a member of both the EAC and the SADC; Burundi, Rwanda, and the DRC are also members of two different blocs).

Regardless of whether optimal regulatory environments and internationalization policies are eventually in place, Africa’s standing as a study destination hinges on establishing more and better-funded research universities that can compete internationally. At present, the high demand for education in SSA has mainly ushered in a flood of smaller, demand-absorbing private providers of inconsistent quality. In Nigeria alone, almost 300 smaller private institutions have applied for accreditation in recent years [83]. These types of institutions do widen access to education, but they are unlikely to turn African countries into international learning hubs. At the other end of the spectrum, the example of South Africa shows there is solid demand for international education at quality universities within the region.

Optimistic observers point to greater regionalization or the “glocalization” of international education in the wake of the COVID pandemic and to the potential of virtual mobility. Branch campuses and online education could reduce the costs of education and help expand capacities if the digital divide in Africa can be overcome. And the sheer number of youngsters reaching university age in SSA in the coming decades—close to 400 million by 2050 [84]—will increase intraregional mobility almost by default.

However, it’s debatable if such developments alone can significantly lessen Africa’s outflow of talent—its students and current or future teachers, professors, scientists, and medical professionals. Without access to quality education and gainful employment, young Africans with financial means will continue to seek education opportunities outside the continent in large numbers. In fact, outward mobility is likely to increase, since growing numbers of countries worldwide, many of them rapidly aging societies, aggressively compete to import more and more international students and immigrants for economic or political reasons—be it to balance university budgets, fill labor shortages, shore up their own health care systems, diversify their education systems, or advance national “soft power.”

What is needed instead is a more balanced and sustainable approach that ensures that student mobility benefits sending countries more directly, akin to a form of reparations—a model that emphasizes “brain circulation” over “brain extraction.” European countries invest significantly in improving the quality and capacity of African education systems, partly because of historical guilt and the specter of mass-scale labor migration across the Mediterranean Sea, as well as to counter Chinese influence [85] and for other reasons. However, too many international educators in Western countries look at Africa mainly as an up-and-coming recruitment market [86] while ignoring the brain drain and social ramifications in sending countries. Professionals in the field should contemplate more ethical models of student recruitment—by trying to ensure that students return home after graduation, connecting them to post-study employment and research opportunities in Africa, or investing more in research collaborations, online programs for African students, or dual degree programs with African universities, as well as by incentivizing more domestic students to study abroad at African institutions. Alternatively, if Western universities would donate just a fraction of the tuition money they receive from international students, they could contribute substantially to the development of higher education in Africa and other regions in the Global South.

1. [87] All data in this section is from the UNESCO Institute of Statistics (UIS). For another comprehensive study on African mobility, based on UIS data, see also: Campus France: Les grandes tendances de la mobilité étudiante en Afrique Subsaharienne. [88]

2. [89] The CAMES member countries are Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, the Central African Republic, Chad, Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Madagascar, Mali, Niger, Rwanda, Senegal, and Togo.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of World Education Services (WES).