[3]

[3]Students from Nigeria and Ghana seeking international education face growing opportunities amid regional development, despite financial and economic challenges.

Abstract:

This study describes the structural factors that drive outbound student mobility in Nigeria and Ghana in the context of overall developments in sub-Saharan Africa. The region will become an increasingly important recruitment market for international students. The main causes of this trend are population growth, lack of access to skilled employment, high levels of outmigration, and capacity shortages in overburdened education systems, coupled with the emergence of larger consumer classes in Africa. At the same time, outbound mobility is mitigated by the lack of financial resources and disposable income in the region, as well as the adverse effects of economic crises, inflation, and weak currency exchange rates. However, rapid growth in outmobility in the region in prior years illustrates that the underlying push factors are likely strong enough to override these limitations. The main beneficiaries of the trend will be host countries with liberal immigration and student visa policies, and open labor markets, as well as countries that offer inexpensive higher education, large-scale scholarship programs, or other benefits that help offset the high cost of international education for African students.

SSA: Regional Overview

International student flows have shifted significantly over decades past. In the 1960s, most international students in the United States came from Taiwan. In the 1970s, Iran then overtook Taiwan as the top sending country. Since then, China has become the predominant sending country of international students worldwide but is now increasingly rivaled by India and other South Asian countries.

Many of the current shifts in student flows are interrelated with socioeconomic transformations and capacity shortages in the education systems of the respective sending countries. Put simply, pursuing education in the U.S. and other Western nations is a desirable option for middle-class students from countries like India, Nepal, or Vietnam, amid a scarcity of quality education and employment prospects at home.

The current international education landscape is more complex and diverse than in the past. But within the next two decades, there will be another significant shift: Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) will emerge as one of the most important recruitment regions for international students worldwide. The factors that will drive this trend are akin to those seen in India over the past 20 years. They include rapid population growth and increased spending power of ascending middle classes. These demographic shifts are combined with severely limited access to well-paid employment and tertiary education in chronically underfunded regional education systems—factors that translate into accelerated outmigration.

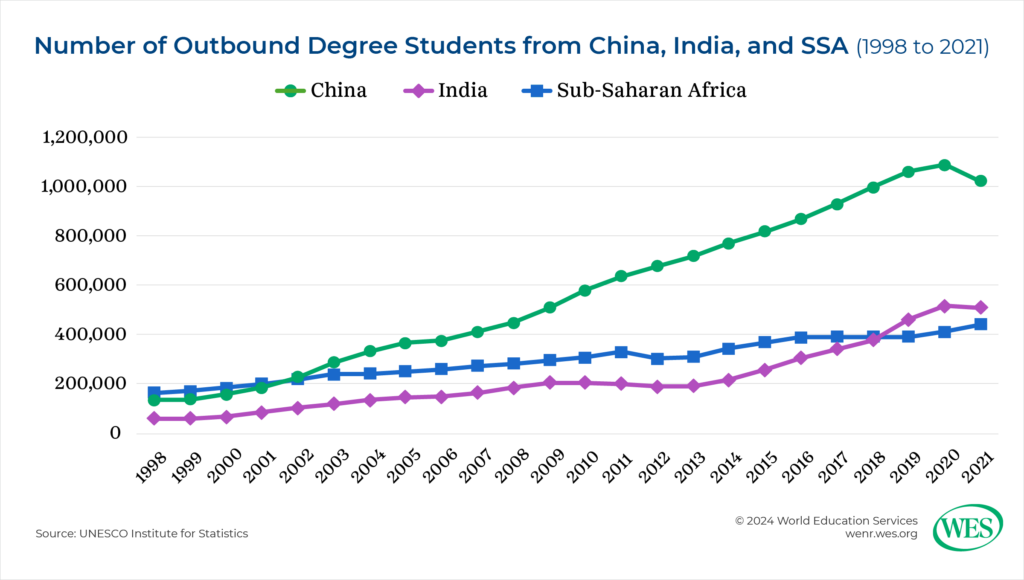

At present, the total number of international students from SSA is still comparatively small, trailing world regions like Europe or the Middle East. But mobility has already spiked in recent years. Between 1998 and 2021, the number of international students from the region increased by nearly 170 percent, from close to 164,000 in 1998 to over 441,000, according to UNESCO statistics.

Whereas traditional recruitment markets in Asia will reach increasing saturation due to greater domestic capacity and adverse demographic trends, the growth potential in SSA is still enormous. Current growth rates suggest that SSA could become the “new China,” with over one million international students by mid-century.

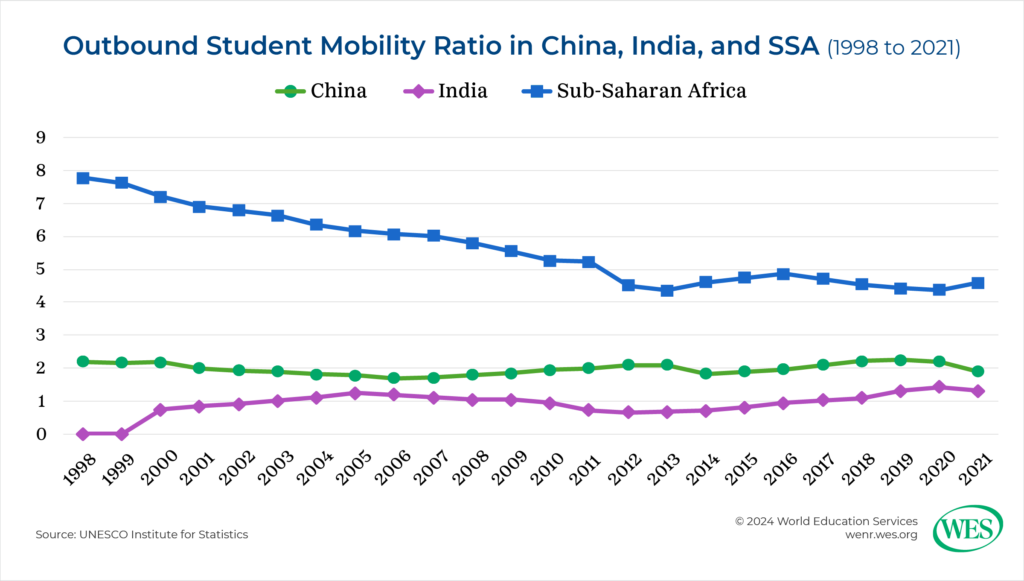

By some measures, SSA is already one of the most dynamic outbound markets globally. While total international student flows continue to be dominated by Asian countries, SSA has one of the highest outbound student mobility ratios worldwide: Proportionally, more than three times as many sub- Saharan students are enrolled in academic degree programs in other countries as Chinese or Indian students.

Drivers of Mobility

Population Growth

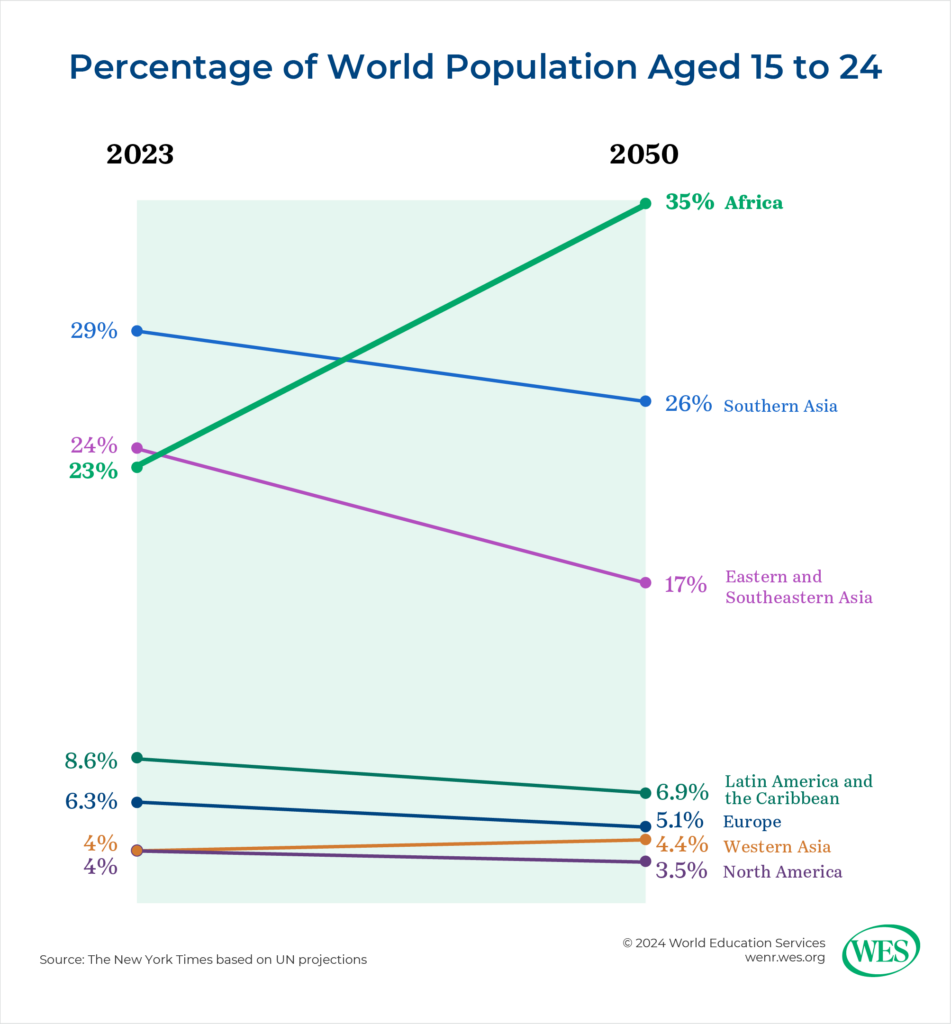

[6]Student outflows from SSA will increase based on demographic trends alone. Some 70 percent of people in the region are under the age of 30; much of the world’s future population growth will take place in SSA. Consider that the UN projects the region’s overall population to jump from 800 million today to 2 billion in 2050—a seismic global shift.

[6]Student outflows from SSA will increase based on demographic trends alone. Some 70 percent of people in the region are under the age of 30; much of the world’s future population growth will take place in SSA. Consider that the UN projects the region’s overall population to jump from 800 million today to 2 billion in 2050—a seismic global shift.

Within the next decade, SSA will overtake South Asia and become the world region with the highest number of tertiary-age youngsters worldwide. There will be close to 600 million people between the ages of 15 and 29 living in SSA by 2050. Massive youth cohorts like this will make up the largest reservoir of potential students worldwide, both domestic and international.

Unmet Demand for Higher Education

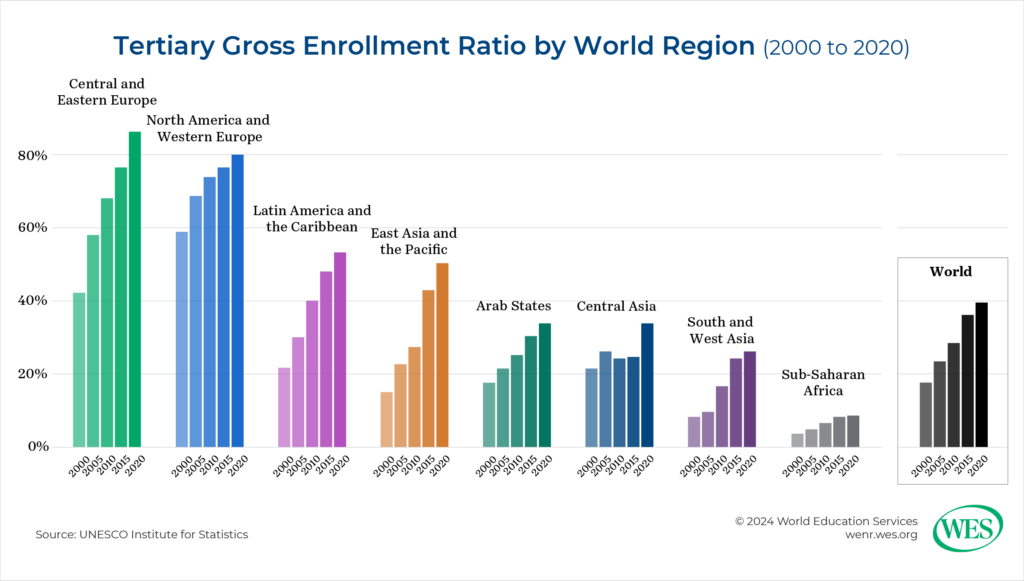

Providing the rapidly growing youth populations in Africa’s urban centers with education and skilled employment is a daunting challenge. Population growth in SSA comes amid severe capacity shortages, funding constraints, and lack of access to higher education. There were only around 1,300 accredited universities in Africa in 2023 for a population of over 1.4 billion people, or roughly one university per one million people. While China, over two decades, succeeded in expanding and modernizing its higher education system to the extent that the return on investment of international education decreased, and outbound student mobility decelerated, the demand for higher education in SSA is still largely unmet. Thousands of additional academic institutions would need to be built in the region, and tens of billions of dollars allocated each year, to meet educational needs.

The reality is that higher education in SSA remains elitist and a privilege of the few. The region has the lowest tertiary gross enrollment ratio worldwide: Only 9.4 percent of people between the ages of 18 and 23 were enrolled in higher education programs in 2021. Most countries in SSA don’t have the financial resources to enlarge their overburdened education systems at scale, which means that the social pressures that drive outbound mobility in the region won’t subside for the foreseeable future.

Quality Problems and Limited Relevance of Tertiary Attainment

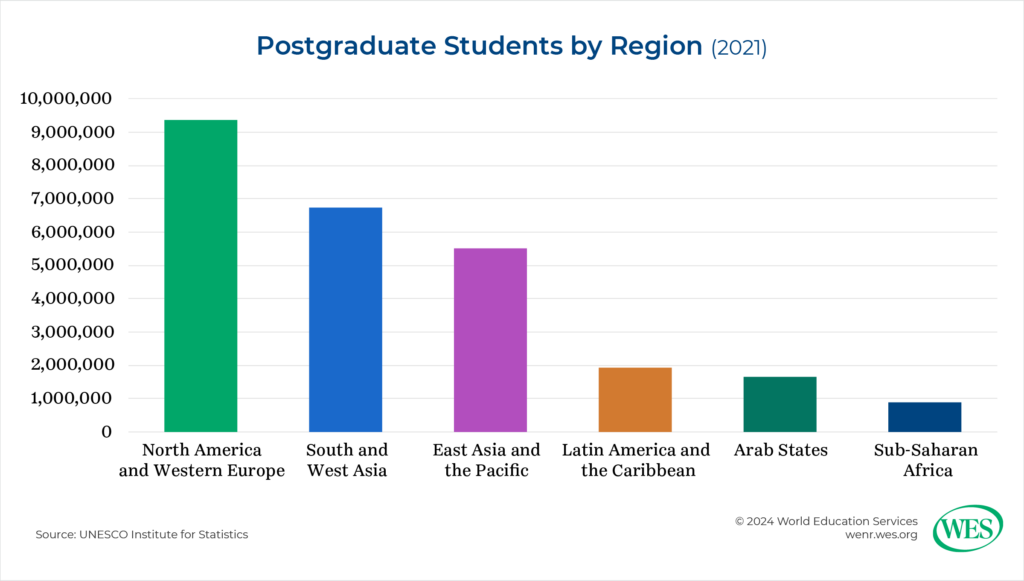

There are several top-quality universities in SSA, notably in South Africa and Nigeria. However, the education systems in the region at large are underdeveloped and not internationally competitive. Many universities are critically underfunded and plagued by shortages of qualified teaching staff, high student-to-teacher ratios, poor facilities, and inadequate technical infrastructure. There’s little capacity in graduate programs, in particular. SSA has the lowest number of researchers per million people worldwide [8]. Research output is consequently very low—Canada alone produces more research papers than the entire African continent. In 2020, there were less than one million graduate students in SSA in total.

What is more, tertiary attainment in SSA does not yield the same social benefits as in other world regions. Graduate unemployment is a major problem in many African countries. In Ethiopia, for example, 42 percent [10] of public university graduates are said to be unemployed. Curricula are often outdated and ill-suited for labor market needs. Universities tend to produce disproportionate numbers of graduates in liberal arts disciplines, while programs in the professions are often scarce and underdeveloped. High-quality academic programs, post-study work opportunities, and immigration pathways in Western countries are consequently major pull factors for African youths.

Obstacles to Mobility

Youth population growth by itself won’t be a major mobility driver unless larger numbers of African students have the financial means to study abroad. The high cost of studying in Western countries is a barrier to mobility in SSA, where international education is only accessible to students from the wealthiest households, mostly in urban centers. To fulfill their dreams of studying overseas or emigrating, some students need to go into considerable debt or sell their houses, while a lucky few obtain scholarship funding.

International student mobility in developing countries is closely related to macroeconomic factors like GDP growth, rising income levels, and stable currency exchang [11]e [11] rates [11]. In terms of outbound academic mobility, countries won’t be on the global map unless they have a critical mass of young education consumers wealthy enough to study overseas.

In Africa, this consumer group is growing, but amid constraints. Despite rapid advances in poverty reduction, most Africans living above the poverty threshold are concentrated in lower income brackets. The number of Africans considered upper middle class by global standards—defined as people living on $20 to $50 a day, expressed in international purchasing power parity—stood at only 2 percent in 2011.1 [12] Weak currency exchange rates and unchecked inflation in countries like Nigeria further diminish the international purchasing power of African consumers. This currently limits the number of international students from the region but also demonstrates that there’s tremendous growth potential should African countries achieve more inclusive economic growth.

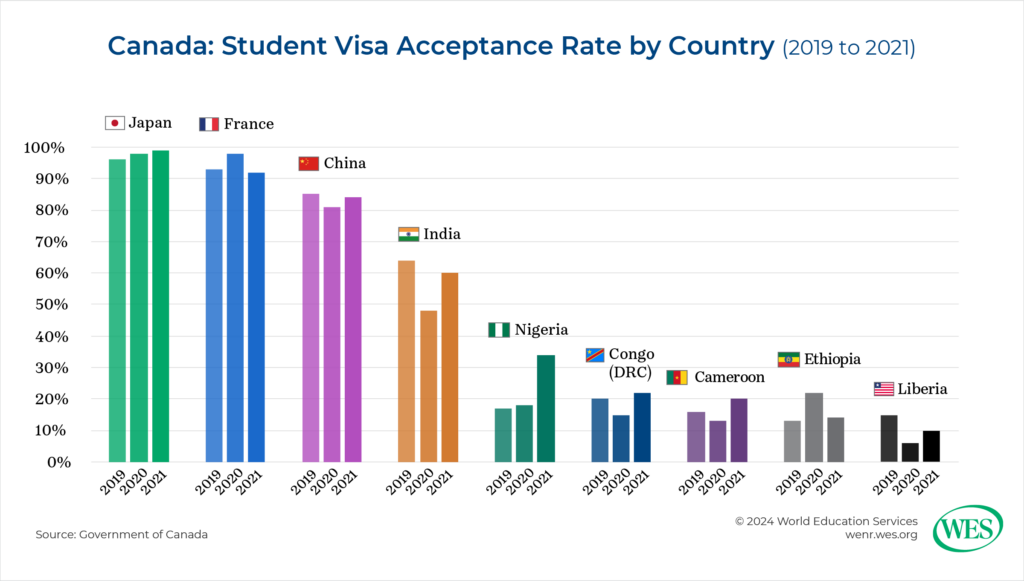

The economic deprivation of Africans also depresses their visa acceptance rates in Western countries, where proof of adequate funds is usually required. African students are approved for student visas at low rates in both Canada and the United States. In Canada, the inadequate financial resources of African applicants are the primary reason for their visa denials. More than 80 percent of failed visa applications of Kenyans and Rwandans, for example, were rejected for this reason in 2022 [13]. In the U.S., African student visa denial rates are the highest of any world region [14].

Scholarships and research grants are obvious accelerators of outbound mobility but are increasingly provided by competitor nations with state-sponsored recruitment strategies. China is now said to be the largest donor of academic scholarships worldwide. It funded 30,000 Africans to study in China between 2015 and 2018 alone [16]. Russia, likewise, is expected to provide government scholarships to 10,000 African students in 2024 [17], while the Indian government in 2015 pledged to fund 50,000 Africans to study in India until 2025 [18]. Scholarship funding in the U.S. and Canada, by comparison, is provided in a much less centralized fashion, mostly by individual institutions, and harder to access.

For North American universities, SSA is still a relatively unexplored recruitment region. Outside of economic hubs like Johannesburg, Nairobi, or Lagos, the international education services industry in the region is underdeveloped compared with more mature markets like China and India. Internet penetration in SSA is low [19]. Many households don’t have regular access to the internet, which limits the reach of direct digital marketing. International education options can be difficult to navigate, so aspiring students often rely on recruitment agents for information. Transnational partnerships and structured exchange programs, likewise, are still few. Only around 6 percent of U.K. TNE students, for instance, were enrolled in SSA in 2022 [20].

1. [21] Or up to $18,250 a year, according to the latest published data from the Pew Research Center [22].