Editor’s note: This article is the third in a series of three, part of a study exploring the structural factors driving outbound student mobility in Nigeria and Ghana, within the larger context of developments in sub-Saharan Africa. Read Part 1 [1] and Part 2 [2] to understand the full scope of this study.

[3]

[3]Outbound student mobility from Ghana has grown significantly, with the U.K. and U.S. being the most popular study destinations, followed by Canada, Germany, and increasingly China.

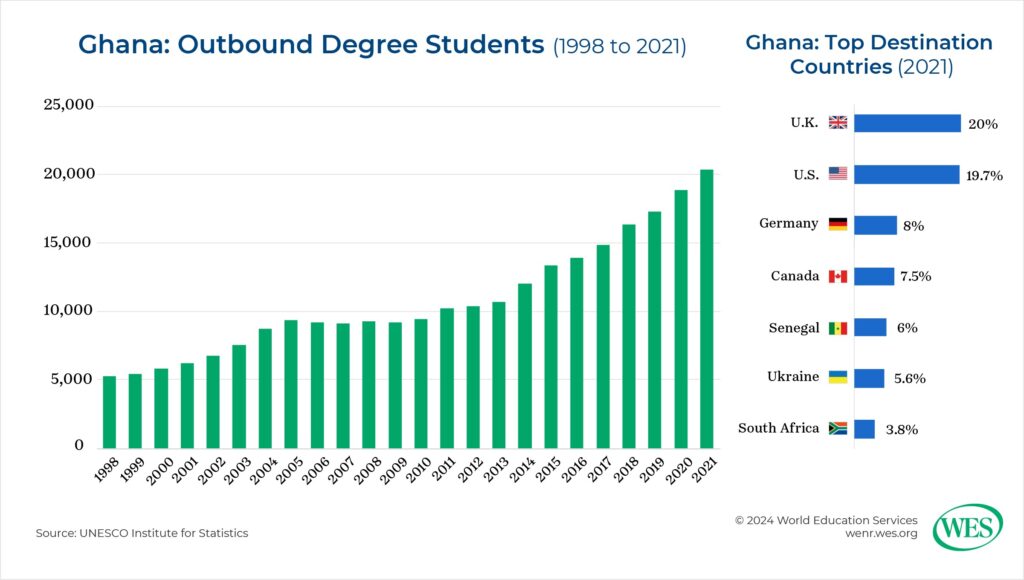

Student mobility trends in Ghana are akin to those in Nigeria, if on a smaller scale. The number of international degree students from the country of 34 million has grown consistently, from 5,270 in 1998 to 20,300 in 2021 (an increase of 285 percent). As in Nigeria, the United Kingdom, the former colonial power, and the United States have been the most popular study destinations. Germany and Canada were the next popular destination countries in 2021. But it is likely that Canada has since overtaken Germany, and that numbers in the U.K. will decline, given the recently enacted visa restrictions. As of this writing, the U.K. has not yet published data for 2023.

Before the Russian invasion in 2022, Ukraine was among the top study destinations of Ghanaians, primarily for students seeking medical education at a comparatively low cost. As noted, China does not report comparable student statistics, but is increasingly popular for students from Ghana and other African countries. Chinese authorities reported that there were 5,552 Ghanaian students in the country in 2016. African countries like Senegal and South Africa register as top study destinations of Ghanaians as well.

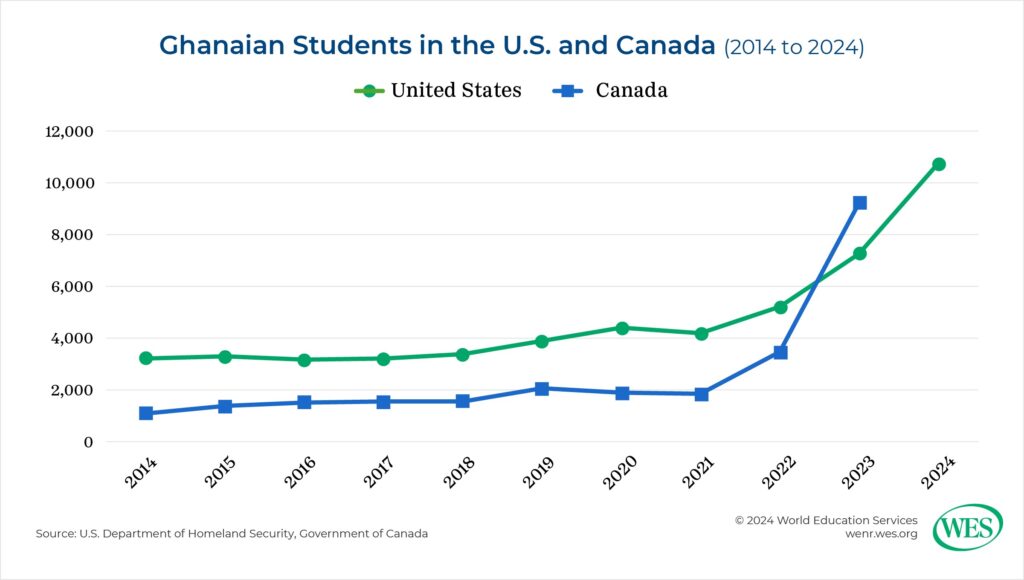

Enrollments of Ghanaian students in the U.S. and Canada surged over the past few years, mirroring the trends observed for Nigeria. Ghanaians currently make up the second fastest growing group of international students in Canada, after students from Guinea, another West African country. The number of active student visas held by Ghanaians jumped by fully 402 percent between 2021 and 2023, from 1,840 to 9,235.

Despite this massive increase, the U.S. remains the more popular study destination among Ghanaians. Ghana is the second-largest African sending country for U.S. institutions; the number of Ghanaian students grew by 157 percent between 2021 and 2024, from 4,179 to 10,749. Some 65 percent of these students are male [5].

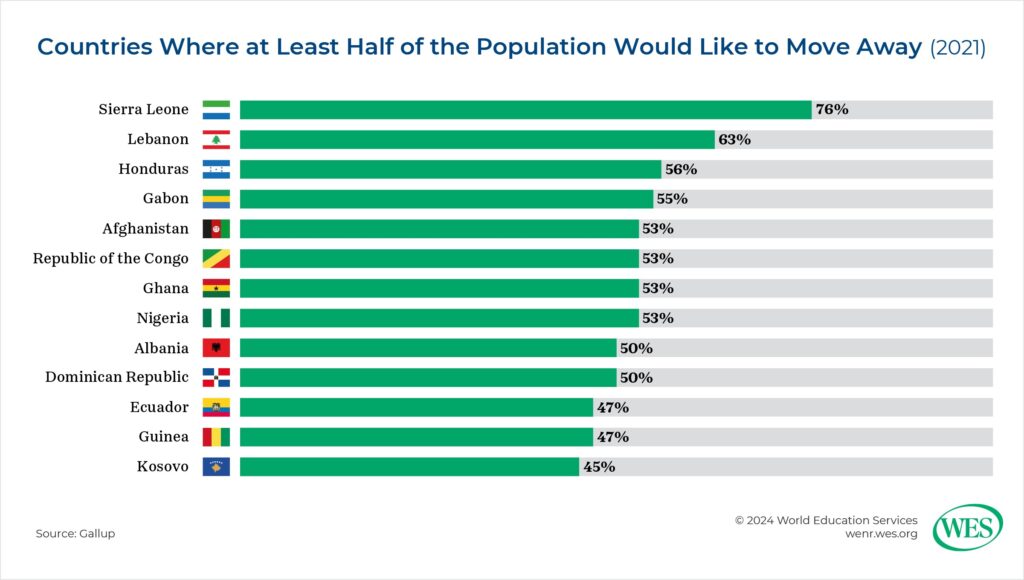

The factors that cause Ghanaians to study abroad are comparable to those in Nigeria. Ghana has a history of outmigration. It is the country with the second-largest number of emigrants in West Africa after Nigeria. In fact, a 2021 Gallup poll [7] found that there are only six countries in the world where more people would like to relocate to another country. Most emigrants tend to be younger and educated. Bettering employment prospects and escaping economic hardship are the most common motivations to leave, followed by pursuing education.

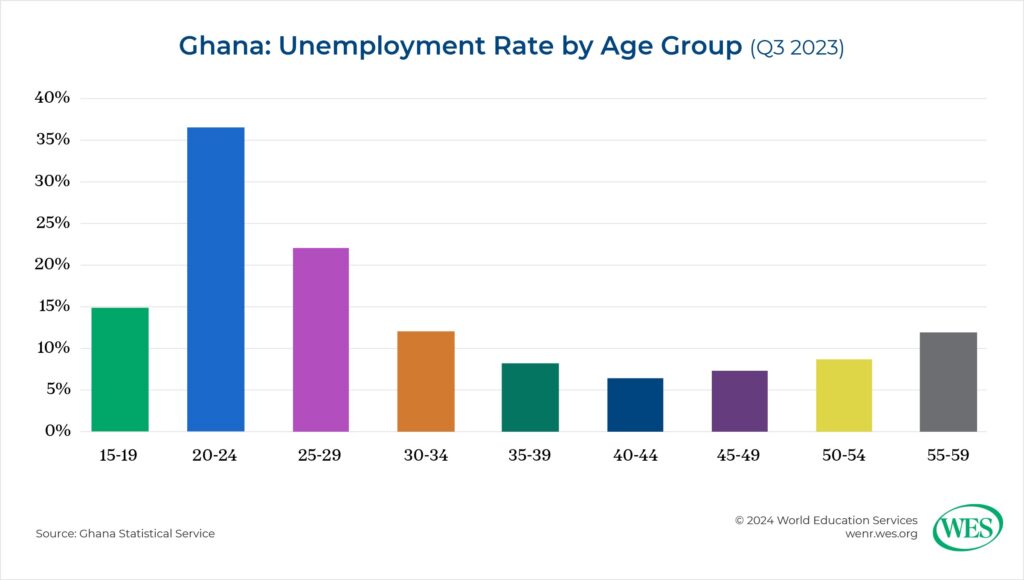

Unemployment, underemployment, and too few opportunities for skills development are key challenges for young people in Ghana. Not less than 36 percent of people between the ages of 20 and 24 were unemployed in 2023 [9]. Tertiary attainment improves the prospects of employment in Ghana, but one in five of the country’s university graduates was out of work in that year.

These economic challenges come amid strong population growth and rapid urbanization. While fertility rates have begun to slow in recent years, Ghana’s population still increases by around 2 percent, or about 700,000 people, each year. More than half of the population is under the age of 19. The country is projected to double in population size, to 70 million, within 36 years. Accra will be a megacity with close to 10 million people by 2050.

Provider Landscape

Ghana’s education system has ballooned in recent decades but struggles to meet the exploding demand for education. Total education spending as a percentage of GDP has fallen from 30.6 percent in 2011 to 13.2 percent in 2022 [11]. State debt as a percentage of GDP reached an all-time high in 2022. Fiscal allocations by the government prioritize the school system, whereas the higher education sector is increasingly underfunded.

Since the1990s, Ghana’s government has progressively shifted public higher education financing to private households by allowing public institutions to collect increasingly higher tuition fees. Most recently, fees were hiked by 15 percent [12] in 2022—a controversial move that resulted in protests at affected universities.

The number of higher education institutions (HEIs) in Ghana grew by 48 percent within just six years. Public universities, which enroll the bulk of students, grew from 9 in 2018 to 16 today. The creation of another four new public universities was announced in 2024 [13]. Aside from these universities, there are 294 additional HEIs, including nursing colleges, teacher training colleges, and university colleges without degree-granting status.

Private institutions account for a large portion of Ghana’s tertiary level providers. After Ghana liberalized its university system in the 1990s, the number of private HEIs spiked from only two in 1999 to over 120 today. This trend notwithstanding, enrollments at private institutions as a share of overall enrollments dropped from around 20 percent in 2012 to 11 percent in 2022. High tuition fees at these institutions inhibit their growth.

As in Nigeria and other African countries, private HEIs usually have limited capacity. The internationally ranked Ashesi University, one of the top private universities in the country, for instance, enrolls only some 1,500 students. In most cases, private HEIs are smaller providers of lesser quality. They help absorb demand by students locked out of the competitive and more highly regarded public university system but aren’t a substitute at the necessary scale.

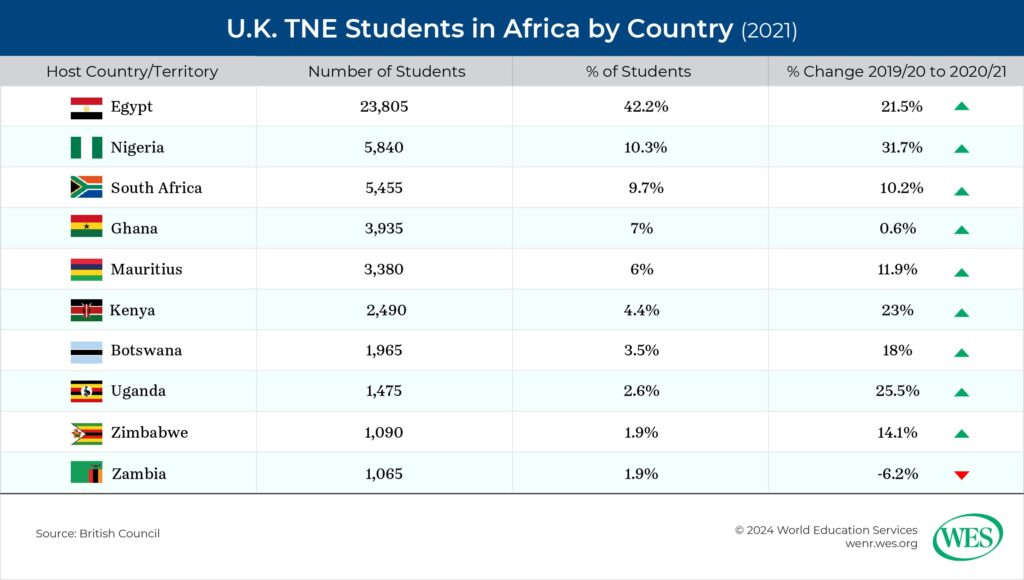

TNE provision in Ghana is growing. Foreign providers view Ghana as a promising market since it’s a politically stable English-speaking country with large untapped demand. Four foreign institutions are accredited as “registered foreign providers” by Ghana’s Tertiary Education Commission, including the U.K.’s University of Sunderland. Another British institution, Lancaster University, in 2024 announced that it would open the first U.K. branch campus in Ghana [14]. Overall, Ghana has been the fourth-largest U.K. TNE market in Africa since 2021.

Distance education offered by domestic providers is increasingly popular in Ghana as well. Remote learning has expanded at double-digit growth rates in recent years. In 2018, some 15 percent of Ghanaian students were enrolled in distance mode, according to the latest available government statistics [16]. But Ghana’s digital learning infrastructure is still relatively underdeveloped, especially in rural regions. Distance education is mostly concentrated in liberal arts and business programs at two major public universities.

Growth in the Number of Students and Capacity Constraints

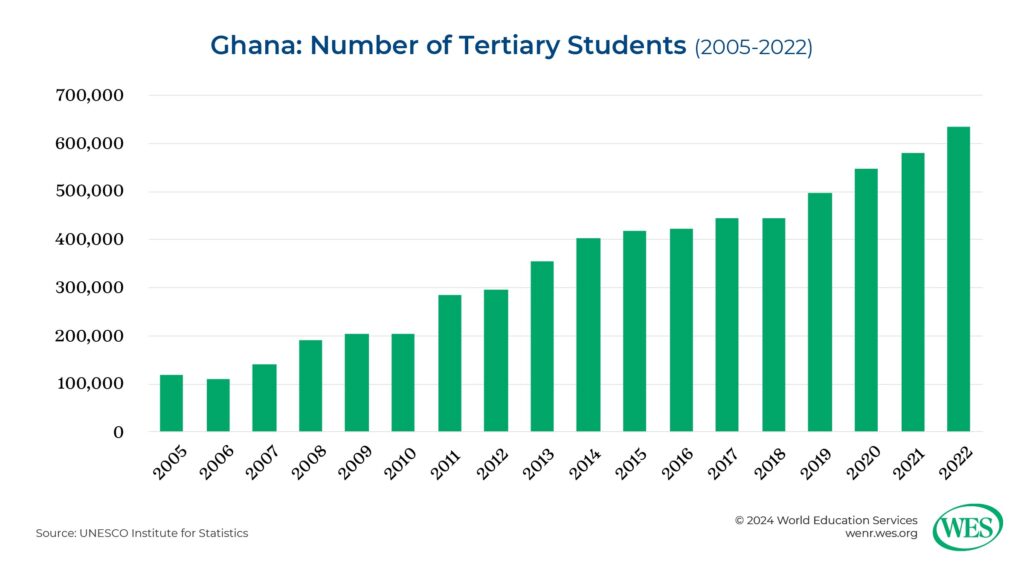

The total number of students in Ghana has skyrocketed more than fivefold within 17 years, reaching 635,000 in 2022. Between 2018 and 2022 alone, tertiary enrollments jumped by 28 percent—a trend that coincided with an increase in outbound student flows by 24.5 percent between 2018 and 2021.

Despite this drastic increase, it’s unlikely that Ghana will bridge its capacity gaps in higher education in the near-term future. Ghana’s tertiary GER has improved markedly over the past few years and exceeds that of Nigeria by several percentage points. But still, only 20 percent of people between the ages of 18 and 23 were enrolled in higher education programs in 2022.

Unlike Nigeria, Ghana doesn’t have a centralized admissions system, so that overall admission rates are harder to determine. However, according to some calculations [18], less than one-fifth of applicants at the University of Ghana, the country’s largest university, are currently being admitted.

As in Nigeria, graduate education is underdeveloped in Ghana. There were only 34,150 students enrolled in master programs, and another 4,076 in doctoral programs, in 2022. This compares with 90,400 master students and 62,430 doctoral students in Malaysia, a country of comparable size with 34 million people.

This low output of graduates with advanced degrees impedes the growth of the university system where more faculty are urgently needed, and teacher-to-student ratios are high. The dearth of postgraduate options also means that many Ghanaians head overseas for graduate school. Fully 75 percent of Ghanaian students in the U.S. are currently enrolled in master or doctoral programs. Fast-growing numbers of Ghanaians also study in terminal degree programs in China—a trend strongly driven by scholarship funding [19].

Growth of the Middle Class

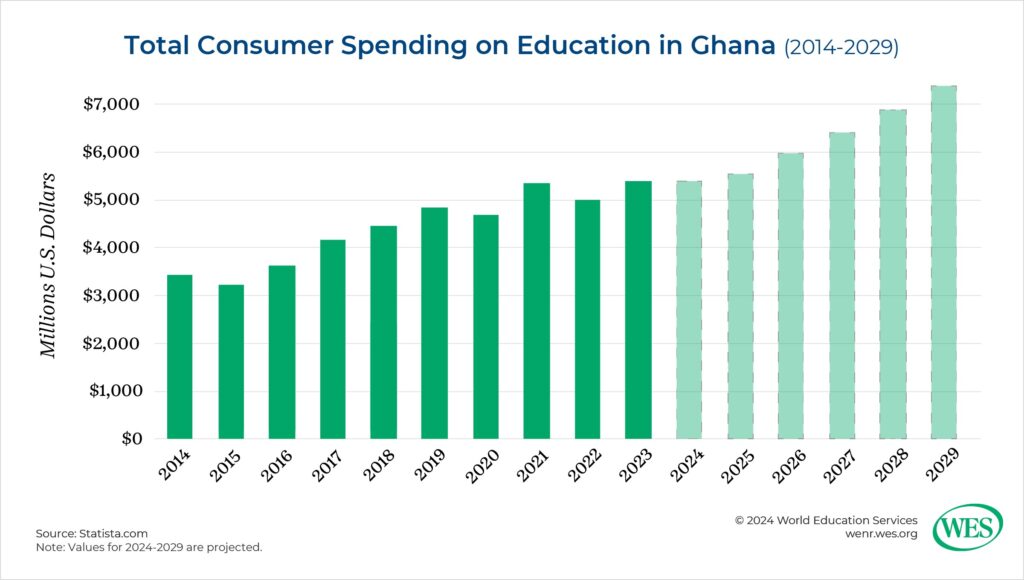

Ghana compares favorably with other African countries in terms of income levels. The country’s middle class has grown substantially by most estimates. Upper-middle-class consumers, defined as people earning between $300 and $1,500 a month, is now said to make up around 14 percent [20] of Ghana’s population. Consumer spending on education is on an upward trajectory and projected to increase in the coming years.

At the same time, Ghana is affected by similar economic shocks as Nigeria. The depreciation of Ghana’s currency, the cedi, is a negative factor that raises the costs of international education for Ghanaian students. In 2024, the cedi declined by 14 percent [22] against the U.S. dollar. Macroeconomic volatility will likely lead to short-term fluctuations in outbound student flows in an otherwise favorable recruitment market with strong growth potential.