[1]

[1]International students share their diverse experiences and challenges in Canada, as educators focus on the impact of recent policy changes on their future opportunities and well-being.

As international educators from across Canada gather in Ottawa the first week in November for the annual conference [2] of the Canadian Bureau for International Education (CBIE) [3], undoubtably one of the most important topics under discussion will be the dizzying number of policy changes in regard to international students announced by the federal government over the past year. The changes come after reporting that revealed exploitation [4] and vulnerability [5] faced by international students, as well as public pressure [6] to reduce the number of temporary residents in Canada.

Among the policy changes over the past year have been caps on new study permits, an increase in the funds students need to secure a study permit, restrictions on the ability of spouses of international students to work, and new requirements to access a post-graduation work permit (PGWP) [7]. These policy changes are discussed in greater depth later in the article.

Though policy changes are shrinking the international student program, Canada remains reliant on international students. International students contribute tremendously to Canada’s economy [8], and many Canadian post-secondary institutions need international student dollars [9] in the face of declining [10] provincial government spending. International students can bring a diversity of experiences and perspectives that benefit university and college campuses. And they also provide a ready supply of skilled workers for Canada’s economy, both during their study and after they have graduated.

It’s worth taking a look at the current state of international student enrollment in Canada and see what might lie immediately ahead, given the new policy changes and some of the shifting currents in and beyond Canada.

The Context of Enrollment Growth and Shifting Policies

The tremendous growth in international student enrollment has roots in funding shifts in Canadian post-secondary education. Chiefly, government funding for public institutions, particularly from provincial governments, has declined since the 2008 global financial crisis [10], even as institutional budgets have risen. Student fees are an ever-growing share of institutional revenue, with international student fees making up a huge percentage of this. According to The State of Postsecondary Education in Canada, 2024 [10] report, released by Higher Education Strategy Associates (HESA), “international student fees have accounted for 100% of all increased operating spending since about 2010.” Revenue from international student fees has increased 554%, versus only 23% for domestic students in the same time frame. The decline in government funding is particularly stark in Ontario, the province with the greatest number of international students by far. According to an analysis from the Blue-Ribbon Panel on Postsecondary Education Financial Sustainability [11] in 2023, provincial funding per student in Ontario is only 44% of the funding level in the rest of Canada for college students and 57% for university students.

This relative decline in public funding has led many institutions to expressly seek out international students to increase tuition revenue [9]. Institutions have been able to tap into international migration [12] and specifically the demand for education [13] among those of other countries, particularly from regions such as South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. The need to attract international students has led to an increase in unethical student recruitment, particularly among unregulated third-party recruiters [14]. Some of these recruiters have provided an overly optimistic portrayal of the potential to stay in Canada after study, as well as the cost of living, ability to secure good housing, and the prospects of working while studying. International study, coupled with the possibility of immigration, may be especially appealing to holders of “weak” passports [15] who are seeking opportunities for global mobility. In CBIE’s biennial survey of international students [16] studying in Canada, about 41% chose to come for the possibility of obtaining permanent resident status. Only 7% of respondents had no plans to apply for permanent residence at some point.

In reality, studying in Canada does not provide a guaranteed path [17] to staying in the country. And as the absolute number of international students seeking permanent residence grows, competition between students increases for a limited number of spaces to transition to PR. In light of mixed messages from government and recent, frequent policy changes, it’s difficult for international students to parse whether they may be welcomed as immigrants.

The federal government often has conflicting policy objectives and confusing messaging around whether it wants study in Canada to function as an immigration pathway. This is made more complex by provincially-run programs. For example, Immigration Minister Marc Miller has recently stated [18] that study permits are for the purpose of education, not immigration. Yet at the same time, the government has announced measures [19] that align post-study work with the needs of the Canadian labour market and published an Immigration Levels Plan [20] that seeks to dedicate 40% of economic immigration places to people already in Canada, such as international students.

To make matters more complicated, Canada has been unclear on whether it accepts “dual intent,” meaning the intention to obtain a temporary visa while also seeking permanent immigration opportunities. The federal government’s guidance to IRCC officers [21] as of 2023 for assessing temporary resident applications demonstrates this. This guidance says both that individual applicants can express dual intent but need to fulfill the terms of their temporary permit and leave Canada when done. It states somewhat incongruously, “Canada actively promotes … programs [that allow for the possibility of immigrating] to foreign nationals… In the case of study permit applicants, officers should take into consideration that the Government of Canada actively promotes study-work-permanent residence pathways to prospective students, and that prospective students (particularly Francophones) are encouraged to indicate that they wish to immigrate to Canada permanently.”

The very rapid growth in international enrollment has led to tremendous challenges for international students themselves. Chief among these challenges has been securing housing [22], as supply has not kept up with demand. In CBIE’s 2023 survey [16], 60% of international students said that “securing accommodations” was a major challenge in the pre-arrival stage, up seven percentage points from the 2021 survey. It was the top-cited challenge at that stage. Additionally, a recent study by Statistics Canada [23] found that international students paid 10% more than Canadians for rent in the same neighbourhoods.

Additionally, as a WES policy brief on the topic [24] notes, “almost daily, media outlets report on student exploitation, their vulnerability to misinformation and fraud, and the impact of poor and limited housing options that have left a disturbing number of students homeless. Canada has witnessed an alarming rise in the use of food banks and deaths by suicide among international students.” International students, who have become important workers in the Canadian economy, have also reported exploitation [25] and wage theft [26] from some employers.

A large percentage of international students, in fact, rely on employment during study to keep afloat financially. Two-thirds of university students and three-quarters of college students in the CBIE survey [16] said that working during study was “absolutely required” for them financially. However, the federal government has recently announced a cap on off-campus work [27] at 20 hours, after suspending any restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic. This poses a hardship on many international students. Additionally, many students have been recruited into programs where there is weak labour market demand within Canada, according to some experts [28].

Some of Canada’s structural issues around housing [29] and health care [30] have been unfairly blamed [31] on international students and other temporary residents. This has fueled growing public concern [32] about the rate of temporary and permanent immigration. Public concerns related to immigration have long been a feature of many other Western countries, particularly in Europe [33] and the United States [34]. This is occurring at the same time as the current minority government face declining public support [35], as polling shows, in large part due to the cost of living and inflation, which some attribute in part to immigrants and temporary residents.

The challenges to the sector of course go beyond what is happening in Canada. Trends in individual countries, both sending countries and other major hosts, also have impacts on the flow of international students to Canada. For example, about half of the world’s population [36] will have gone to the polls in national elections by the end of 2024, including some of the world’s major democracies, such as France, India, Mexico, South Africa, South Korea, Taiwan, and the U.K. Arguably the most consequential of the year, the U.S. presidential election, has resulted in the reelection of former President Donald Trump [37]. These elections will likely shape global mobility trends, including those impacting Canada, in the immediate years to come.

A Profile of International Students in Canada Until the Recent Policy Changes

We don’t yet have full data for 2024, so we don’t yet know the full implications of the policy changes announced over the course of the year. We do have some preliminary data and analysis, but before turning to that, it’s worth looking at the growth and profile of international students that led up to these policy changes.

How has the size of the international student population changed?

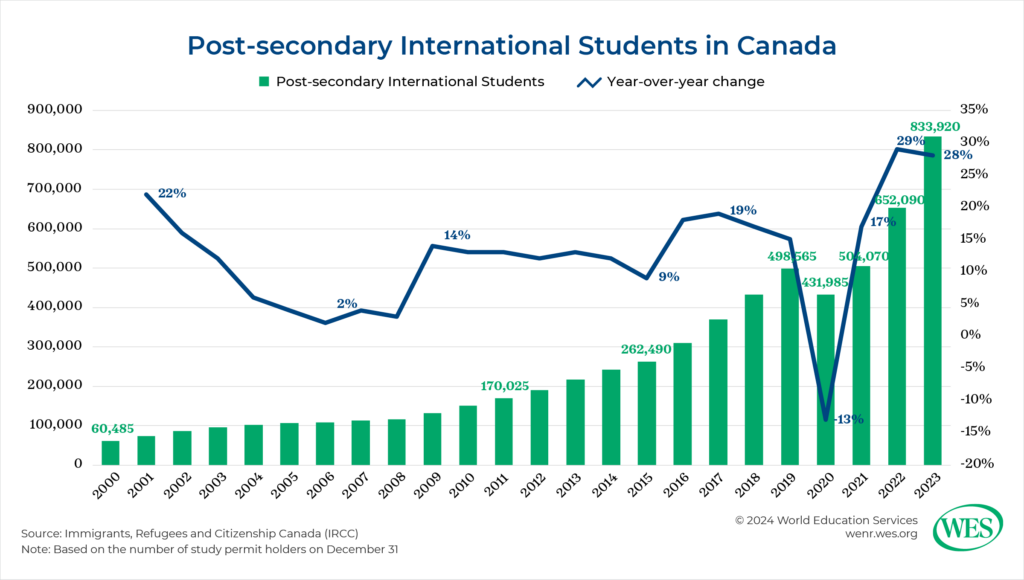

While there were over one million international students in Canada in 2023 at all levels (including K-12 students), there were 833,920 post-secondary international students that year, based on the number of valid study permits [38]. This has been the result of tremendous growth, about 286% in post-secondary international students over a 10-year period. There has been uninterrupted growth with the exception of 2020, the main year of the COVID-19 pandemic, during which the share of international students plummeted by 13%.

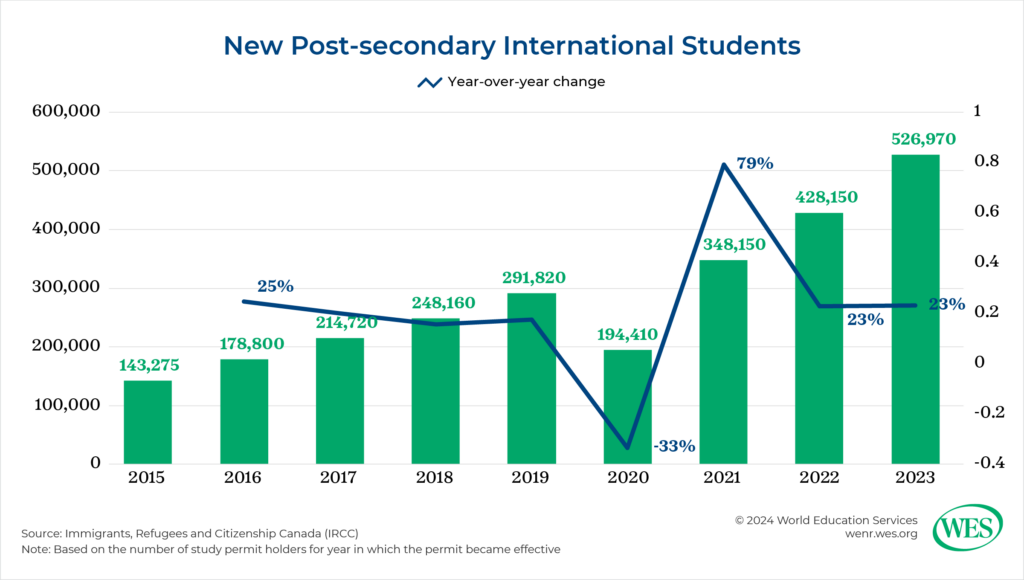

As the graph above shows, this growth has particularly accelerated since 2020 and the phasing out of pandemic restrictions. In 2021, the growth rate overall immediately bounced back to 17%, a similar growth rate to the years immediately prior to the pandemic. New student enrollment [40] in 2021 grew 79%, reflecting pent-up demand from the public health restrictions, a phenomenon that occurred in other major host countries, such as the U.S [41]. In the last two years, total growth has pushed up to 29% in 2022 and 28% in 2023.

Where do international students come from?

IRCC data do not separate out post-secondary and non-post-secondary students by country of citizenship [43], unfortunately. But we can still gain important insights into countries and regions of origin for post-secondary international students.

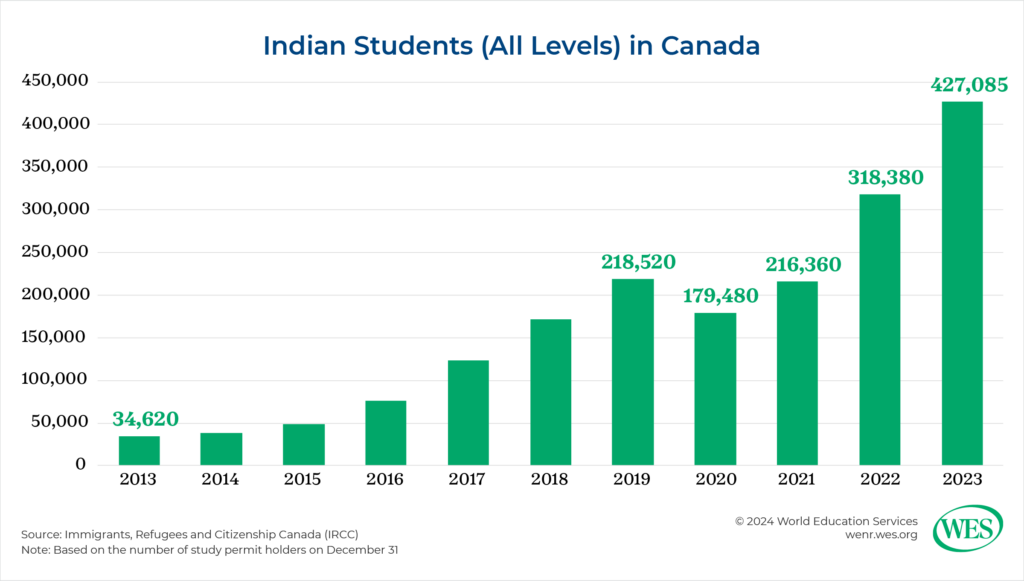

In recent years, India has been dominant. In 2023, there were 427,085 Indian students [43] (at all levels) in the country, a 34% increase from the previous year. Canada has become the top destination for Indian students, eclipsing the U.S. [41] in the 2018/19 school year. Around that same time, they surpassed Chinese students to become the top country of origin for international students in Canada.

India has driven much of the growth in international students. Indian students went from 11% of all international students in 2013 to 41% in 2023. About 1.3 million Indian students [44] studied abroad in 2023, likely the largest number in the world. The main factors [45] have long been the lack of quality seats at the graduate level in India, particularly in the popular fields of engineering and information technology, and the opportunity to access work and residency opportunities in other countries, such as Canada, after graduating.

There are some indications that growth in newly enrolled Indian students [47] was slowing slightly even prior to the new policy changes. Growth in new Indian students was 33% in 2022 and declined to 23% in 2023 – still quite robust. Some of this mild decline is likely due at least in part to diplomatic tensions [48] between Canada and India that go back to at least 2018. Relations deteriorated rapidly beginning in September 2023 after Prime Minister Trudeau publicly accused the Indian government of backing the assassination of Sikh separatist leader Hardeep Singh Nijjar, a dual citizen of India and Canada, in Surrey, British Columbia. The Indian government denied involvement. Since then, both countries have exchanged tense words, scaled back trade relations, and recalled some of their diplomats, among other actions. In October 2024, both countries began expelling each other’s diplomats after Ottawa again accused the Indian government of clandestine activities within Canada. In addition to geopolitics, there are indications [49] that Indian students are also sensitive to the high cost of living and softening labour market in Canada, along with reports of deaths [50] of Indians in the country.

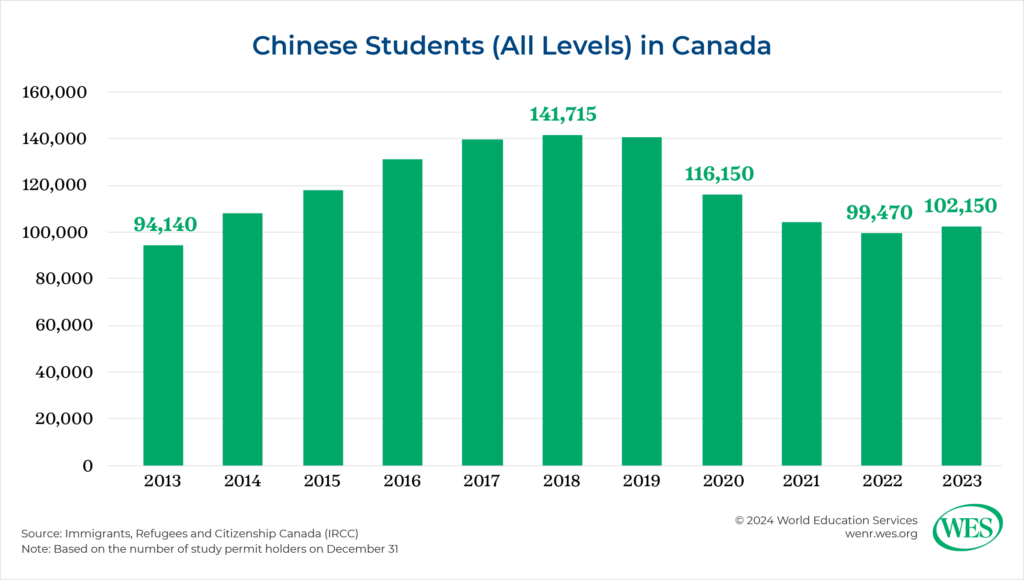

China remains the second top country of origin but presents a different story from India. There were 102,150 Chinese students [43] in 2023, only about one-quarter the number of Indian students. The number peaked in 2018 at 141,715 and then declined 28% over the next five years. After the early years of the pandemic, the number continued to decline steadily while most other top source countries rebounded quickly. There was a slight uptick of about 3% from 2022 to 2023. There have been similar trends in the U.S. [51] and Australia [52], with the United Kingdom [53] slightly bucking the trend. (The U.S. is still by far the top destination for Chinese students.) The reasons for this [54] are complex and have a lot to do with internal factors in China, including increased capacity and quality in China’s own higher education system and a robust economy, though geopolitical tensions between China and Canada (and Western countries more generally) have also played a role.

Rounding out the top five countries of origin [43] are the Philippines, Nigeria, and France. Long major sources of immigrants for Canada, the Philippines and Nigeria have posted huge growth of international students lately. The number of students from the two countries grew 51% and 113% respectively, from 2022 to 2023. In 2021, they were the 8th-and 10th-largest senders. By contrast, France has been a steady, long-time top sender, certainly due to the significant number of Francophone institutions and programs. Canada is the top destination for French degree-seekers going abroad, just ahead of fellow part-Francophone country Belgium (the second top destination), according to Project Atlas [56]. French international students go in smaller numbers to other predominantly Anglophone countries, with the U.K. being the main exception due likely to its proximity and regional integration.

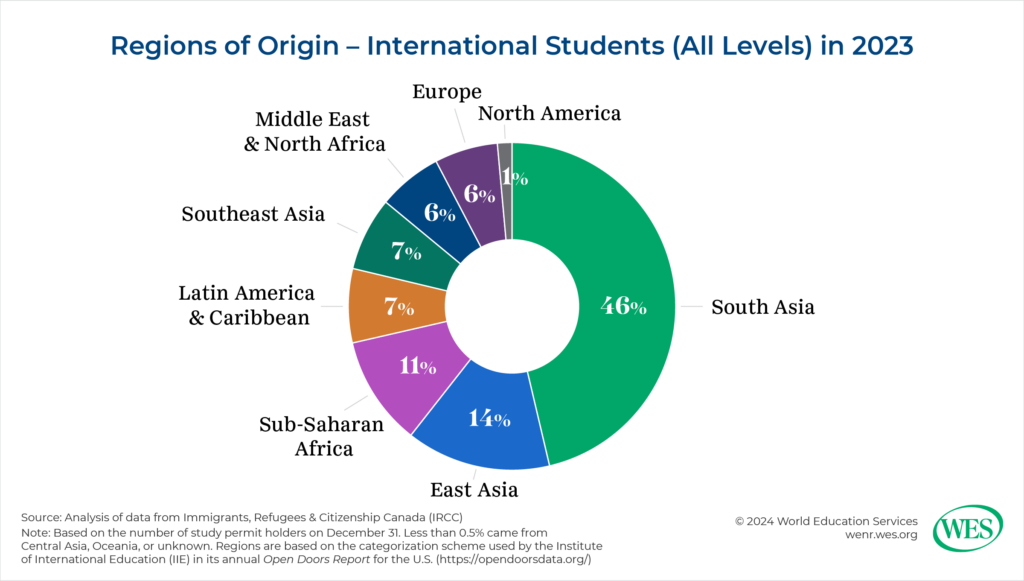

When broken down by major world regions,1 [58] South Asia dominates, with India accounting for the vast majority of students from this region. South Asians make up nearly half of all international students in Canada. East Asia and sub-Saharan Africa follow. In general, there has been broad growth from South Asian and sub-Saharan African countries. Nepal was up 166% from 2022 to 2023 and up an astounding 25-fold in the last five years. In addition to Nigeria, there has been significant growth from Ghana (167% from 2022 to 2023), Cameroon (100%), and Côte d’Ivoire (88%) among sub-Saharan African countries. There has been a broad outflow of students from South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa in general, with many other major destinations experiencing large growth from these two regions. By contrast, East Asia has been witnessing some declines among major countries of origin. In addition to China, enrollment from South Korea and Japan, long major senders, has also declined recently.

Where do international students go within Canada?

Ontario continues to be the top destination province [38] for international students by far, with 453,485 post-secondary international students in 2023. British Columbia (BC), Quebec, and Alberta follow.

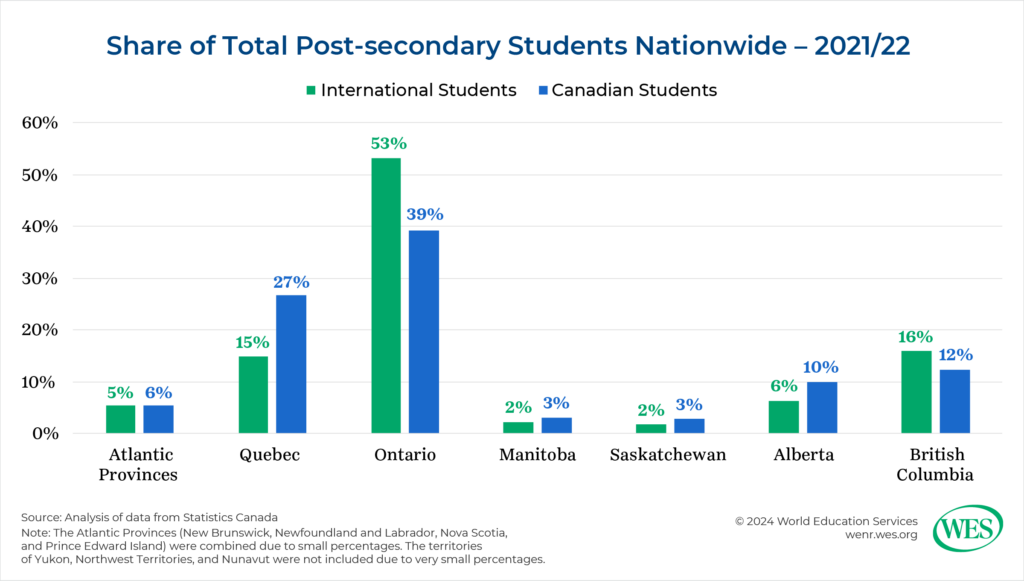

When comparing the share of international students to that of Canadian students,2 [61] international students are heavily overrepresented in Ontario. That province accounts for 54% of total post-secondary international enrollment nationwide, compared with 39% of Canadian students, in 2021/22 (the latest year available), according to an analysis of post-secondary data from Statistics Canada [62]. BC has a slight overrepresentation of international students to Canadian, at 16% versus 12% of the respective nationwide totals. By contrast, Quebec and Alberta have higher shares of Canadian students relative to international students. Quebec, for example, has 27% of total Canadian enrollment versus only 15% of total international enrollment. All other provinces, including the Atlantic Provinces collectively, have relative parity between the two groups.

How do international students figure into the broader population?

Canada has the top percentage of international students of total higher education population, at nearly one-third (30%) in 2023, according to Project Atlas [63]. This is the largest ratio of international students to total higher education enrollment among the 23 countries that are members of the Project Atlas consortium [64], representing virtually all of the major international student destinations. For comparison, the percentage of international students in Australia and the U.K. are 24% and 22% respectively. The U.S., which has a significantly larger higher education system (in both enrollment and number of institutions) than the other three countries, has only 6% international student enrollment.

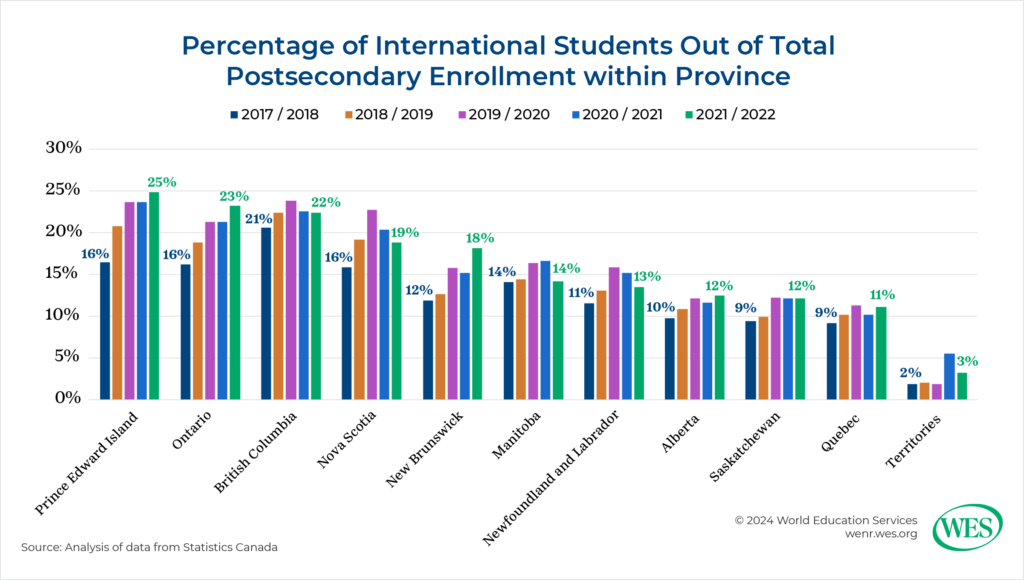

At the provincial level in 2021/22,3 [65] the international student enrollment in the post-secondary systems in Ontario and BC were both nearly one-quarter each. Quebec and Alberta had considerably lower percentages of international enrollment. Interestingly, the province with the largest percentage of international enrollment was Prince Edward Island (PEI), the least populated province and smallest post-secondary education system. PEI’s international enrollment was 25%, just above that of Ontario, the most populous province. This shows the success of major recruitment efforts [66] over the years within PEI and the Atlantic Provinces more broadly that has often included funding from the federal government.

Most of the provinces have experienced at least some percentage growth over the last five years or so, showing that international enrollment has grown faster than domestic enrollment in many provinces. Manitoba’s proportion of international students has fluctuated but largely remained the same over time. (There has been very slight growth in international enrollment in the three territories collectively.)

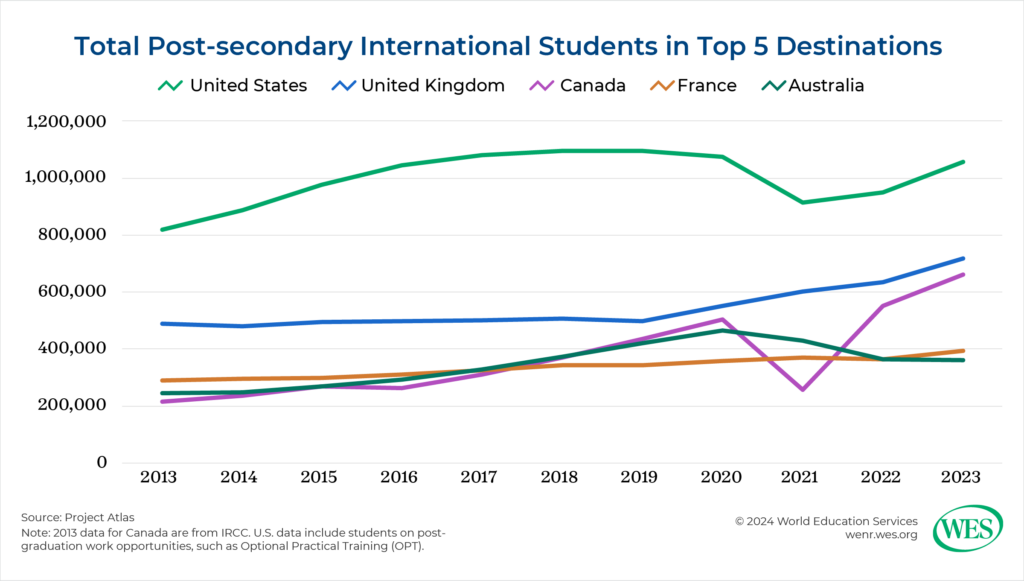

How does Canada’s growth compare with that of other countries?

While many major study destination countries around the world have experienced growth, particularly as the number of globally mobile students continues to expand, Canada’s growth has been particularly rapid. There are some discrepancies in the available comparative data, but Canada has been rapidly closing in on the second-place U.K. Canada’s global market share also went up to 10% in 2023 from 6% in 2016. All that said, the policy changes announced throughout 2024 intended to both bring down total enrollment and slow growth, may impact this, though there are signs that there is slowing growth in other destinations, including the other major Anglophone destinations. Australia and the U.K., for example, have also announced restrictions [68] that may slow growth in these countries.

What is the economic impact of international students on Canada?

A 2023 report from Global Affairs Canada [8] found that international students “contributed $37.3 billion to economic activities in Canada in 2022,” translating to about 1.2% of Canada’s GDP. These contributions included overall spending from international students, as well as tourist dollars brought in by visiting friends and family, minus any Canadian financial aid provided to students. That year, international students also contributed $7.4 billion in taxes and helped support 361,230 jobs. Without them, Canada would have a profoundly different post-secondary landscape.

What do international students think of their time in Canada?

The most comprehensive data for this comes from CBIE’s biennial International Student Survey (ISS) [70], released in report form as The Student Voice. The most recent report [16] is based on a 2023 survey that captured 32,591 responses from across Canada.

Overall, 82% of respondents were satisfied or very satisfied with their study experience in Canada. At the same time, 18% were not satisfied. Ontario had the highest rate of students who were dissatisfied or very dissatisfied, at about 20%, while Quebec had the highest rate of overall satisfaction at 87%.

A good metric for understanding satisfaction is the likelihood in which an individual would recommend Canada or their institution to others. Only 41% of respondents would recommend Canada, down from 64% in 2021. The percentage of Indian students who would recommend Canada dropped from 70% in 2021 to 37% in 2023, down about one-third. The percentage of Indians who would recommend their individual institution also declined to 43%, down 10 percentage points. (The report does not give overall percentages for those who would recommend their individual institution or not.)

It’s important to keep in mind that these responses were gathered before the major policy changes announced in late 2023 and beyond. They reflect the experiences of international students in the lead-up to these changes. The drop in relative numbers who would recommend Canada and their individual institution should be concerning. These likely reflect the challenges that international students have faced – from securing housing to academic and cultural adjustment – once on campus and in their host communities.

Recent Policy Changes and What We Know About Their Effects So Far

Beginning in late 2023, federal policy changes began rolling out at a rapid clip. In December 2023, the federal government announced that it would require [71] incoming international students to demonstrate that they have access to $20,635, instead of the original $10,000 requirement, as well as upfront travel and tuition payments. This requirement may be adjusted annually based on the cost of living.

In January 2024, the government announced a cap [72] on study permits in undergraduate programs, making a reality of a policy that had been hinted at for several months. This measure introduced a cap of 364,000 study permits in 2024. Later in the year, the government announced caps for subsequent year at 437,000. The caps were situated in government criticism of problems [9] associated with private college “puppy mills.” However, the caps apply to all provinces, not merely those private colleges or the provinces with the most rapid growth. It is also notable that data show [73] that most international students are enrolled in public institutions, and these institutions have exhibited the most rapid growth.

The January changes also made study in Canada potentially less attractive by limiting access to spousal work permits for certain international students. Under the new rules, only spouses of study permit holders pursuing master’s or doctoral studies were eligible for a work permit. Spouses of international students pursuing other levels of education would no longer be eligible.

Many commentators have noted [68] that the government is reacting to the public perception that immigration, including particularly temporary immigrants such as international students, has grown too fast. At the same time, there is acknowledgment by many that international student enrollment in Canada has grown so precipitously that the higher education sector has struggled to accommodate [74] international students, notably in housing [75], and tend to their unique needs.

What has been the impact of the policy changes?

As mentioned previously, we don’t have full data yet to know the immediate effects of the federal government’s recent policy changes. But some interim data and analysis can provide a few clues.

At the time of writing, the only available data on study permits in effect [40] were available through July 2024. When comparing the first six months of 2023 with the same period in 2024, there was only a 1% decline in international students. This may not seem like a lot, but there are two important things to keep in mind: One, there has been nearly continual growth in international students, at least in the last few decades, until this year. More importantly, there is a lag until the policy changes will start having really noticeable effects on international student enrollment.

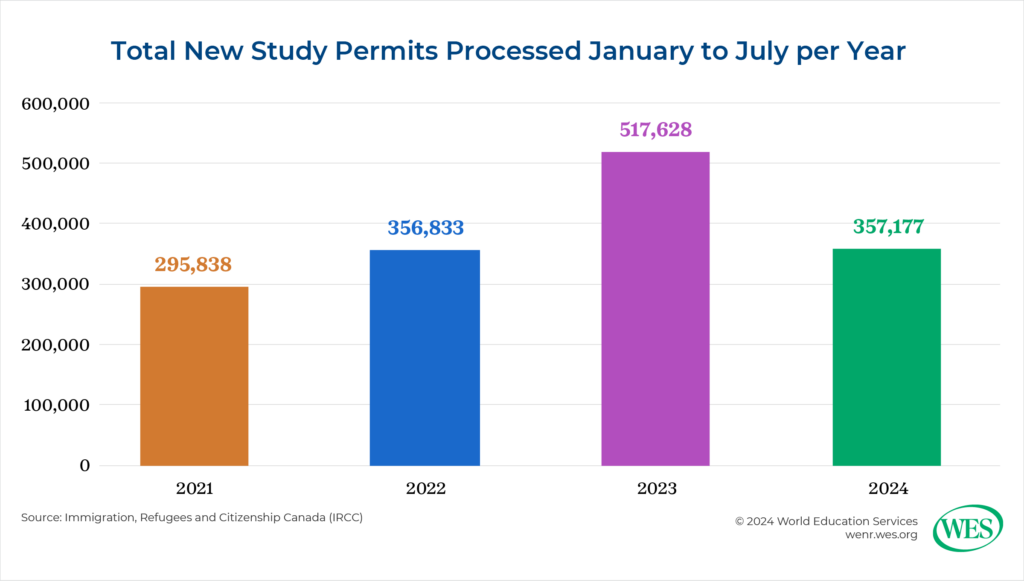

A more telling sign of coming decline is the data on study permits processed. From January to July 2023 to the same period in 2024, total study permit applications processed [77] were down 31%. The number, however, was similar to that of the same time period in 2022. Indian applications are down 56%. Processed applications were down for every single one of the top 10 sending countries except Vietnam. The 31% overall decline in the first half of the year is not too far off a projection made by ApplyBoard [78] that total study permits will decline by 39%. ApplyBoard’s projection is for 522,597 study permits to be processed in 2024, down from 862,534. ApplyBoard estimates that, at a 51% approval rate (based on recent trends), there will only be 231,000 new study permits issued, much lower than the government’s cap of 485,000.

Many in Canada’s higher education and international education sectors have hoped that prospective students would simply shift where in Canada they study, moving from high-volume provinces (notably Ontario and BC) to other provinces, and from certain types of institutions to others. In theory, the cap allocation system would allow some provinces to grow their numbers. However, there is some indication [78] that many students are simply shifting to other countries or even staying home. Some market research surveys of prospective international students have indicated a notable drop in interest in Canada. IDP’s Emerging Futures Report 2024 [79], for example, has found that interest in Canada has declined 9% from the previous year, allowing Australia and the U.S. to move ahead. Additionally, the largest percentage of those who have withdrawn from the process of studying in another country have done so from Canada more than from any other country in the survey. Some have said they are shifting focus to Australia or the U.S. in particular.

Looking to the Future

The policy changes over the past year have been an attempt to slow the growth in international student enrollment, but many have voiced concern that it has damaged Canada’s reputation as a good place to study and immigrate. The effects of this reputational damage may be felt long beyond 2025. New international enrollment looks as if it will drop below the caps for both 2024 and 2025. At the same time, there is a real need to address strategic and funding issues relating to the post-secondary sector across Canada. This need will likely become more urgent with fewer international student tuition dollars flowing in, but under division of powers, this direction must be set at the provincial rather than federal level.

Canada would benefit from taking a holistic view of education, including a consideration of the role of international education and a strategy for a healthy international student mobility program. It is clear that both Canadians and international students stand to benefit from international student mobility. But those benefits are best realized when it comes with a comprehensive plan to achieve those benefits.

WES has provided recommendations [24] for focusing on healthy growth and ensuring that international students thrive in Canada. These recommendations include:

- Access to clear, accurate, transparent information

- Enhanced accountability mechanisms and oversight in the post-secondary sector

- Regulation of education agents in the post-secondary sector

- An expanded scope for federally funded settlement services to include international students

- Clear, predictable permanent resident pathways for students

Government has an important role to play in implementing these recommendations. But regardless of federal policy regarding numbers of students, there is much that institutions and their partners can do. They can push for more sustainable funding from government and other sources. As the first recommendation notes, institutions and their recruiters should ensure that students are getting accurate information about studying at their institution and in Canada in general, including about cost, access to employment, and pathways to stay in Canada after graduation. Perhaps most importantly, they can work toward ensuring that the international students they enroll are well supported and have the best experience possible. This can help ensure that Canada and Canadian institutions are seen as welcoming places where students receive a top-quality education. Word-of-mouth referral is one of the best promoters of Canadian education.

It will take a whole-of-sector approach that focuses beyond limiting numbers of students to ensure healthy, sustainable enrollment of international students that is good for the students themselves, institutions, and Canada as a whole.

1. [80] Based on analysis of IRCC data [43]. Regions are based on the categorization scheme used by the Institute of International Education (IIE) in their annual Open Doors Report for the U.S. (https://opendoorsdata.org/).

2. [81] Based on an analysis of available data from Statistics Canada [62].

3. [82] Based on the same analysis as above.