By Nick Clark, Editor, World Education News & Reviews

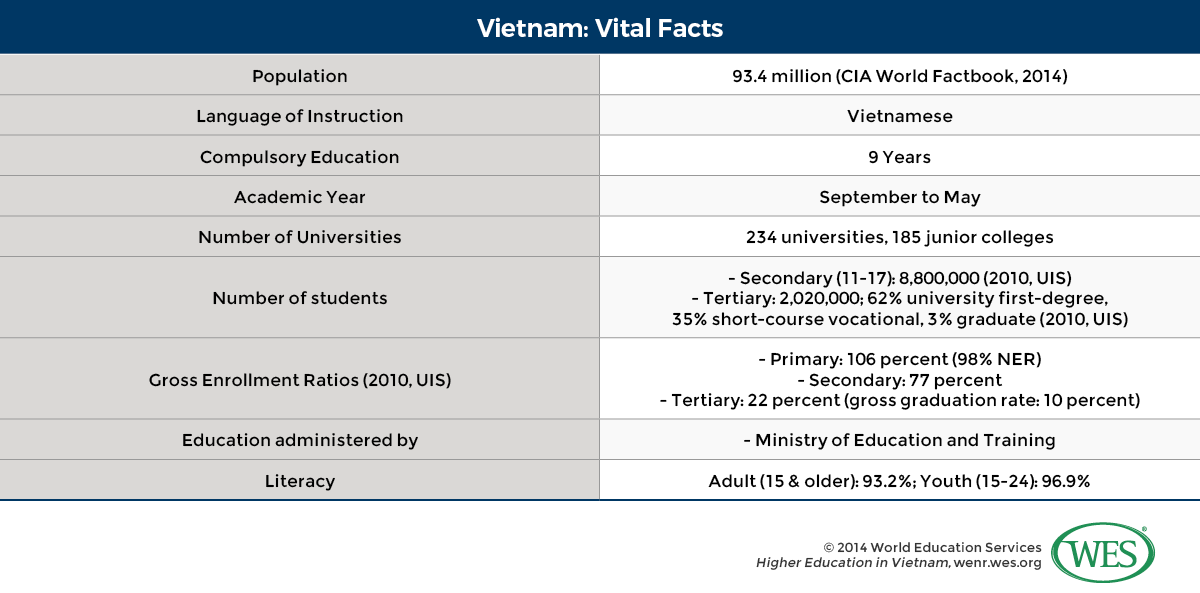

Enrollment at the tertiary level has grown dramatically in Vietnam over the last decade, with the national gross enrollment ratio (college enrollment as a percentage of the total college-age population) rising from 10 percent in 2000 to 16 percent in 2005, and 25 percent last year, according to data from the UNESCO Institute of Statistics. However, the system faces a raft of challenges in responding to the employment needs of Vietnam’s growing economy, especially as it seeks to climb the value chain away from a focus on low-wage manufacturing towards modern industry and innovation.

In this article, we offer an overview of the Vietnamese higher education system, the challenges it faces, and the reforms needed to improve. In addition, we touch on the current mobility trends of Vietnamese students abroad, finishing with a look at some of the most commonly seen academic credentials, including a file of sample documents and advice on what credentials to request when evaluating Vietnamese files and how best to convert grades.

This article is offered as a supplement to a profile of the secondary system we published last year, and which can be found here [3].

Mobility Trends

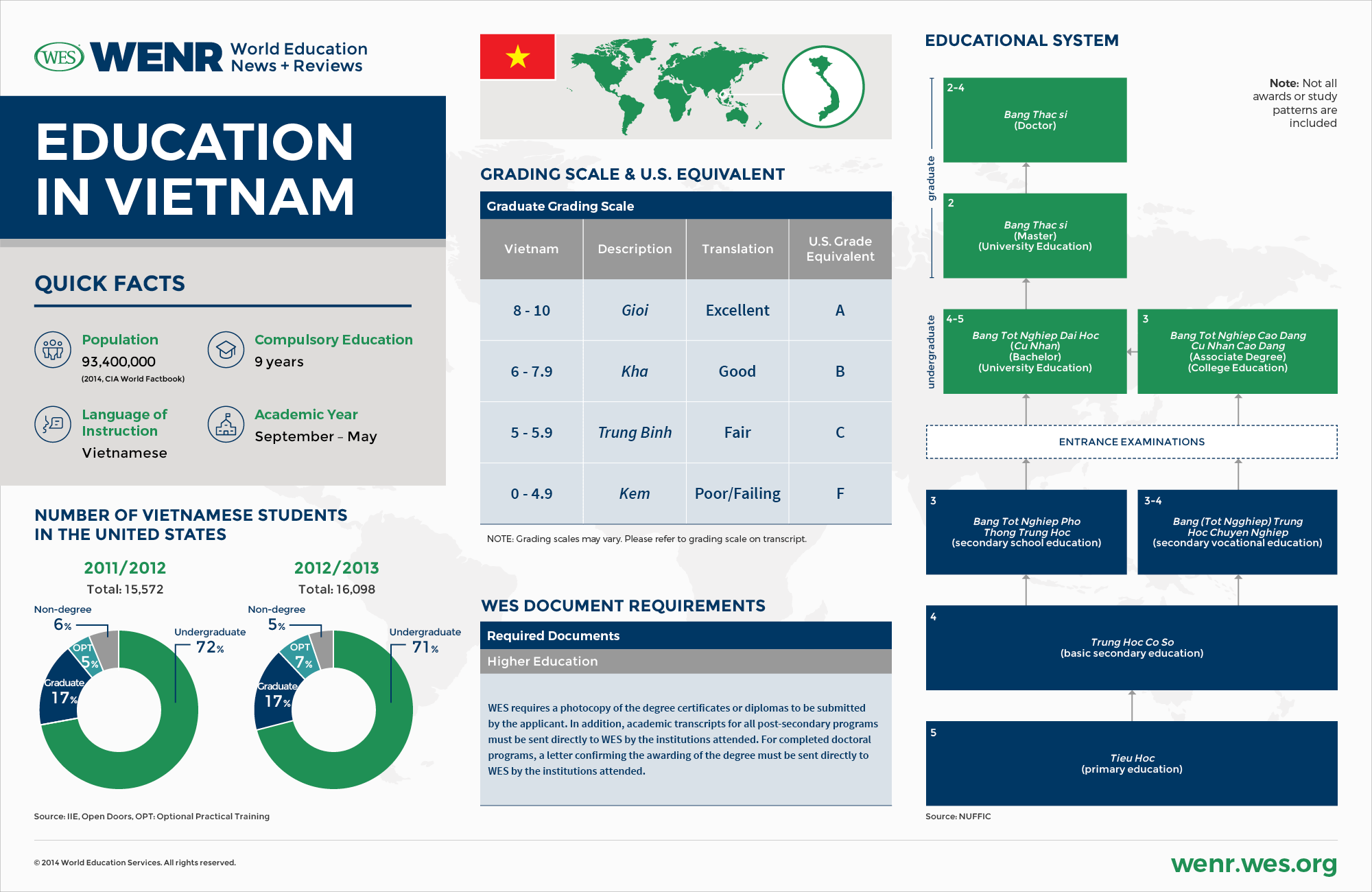

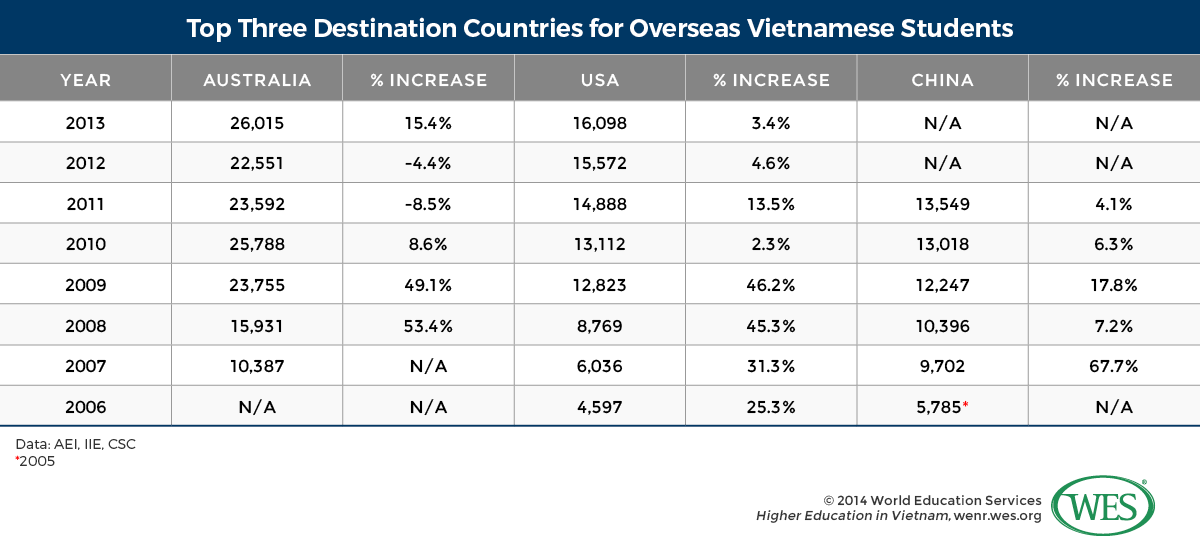

Vietnam has risen to become a significant source of international students for a number of countries around the world, most notably Australia and the United States which, combined, enrolled 36 percent of the approximately 106,000 overseas Vietnamese students in 2012. China is the other major destination of choice for Vietnamese students, enrolling 13,500 in 2011, while Asia on the whole accounts for an estimated 34 percent of international enrollments (36,000). This share is likely to grow, according to observers, who point to the price sensitivity of Vietnamese students and recruitment efforts of countries like Singapore and Taiwan, both of which are increasingly popular destinations for Vietnamese students.

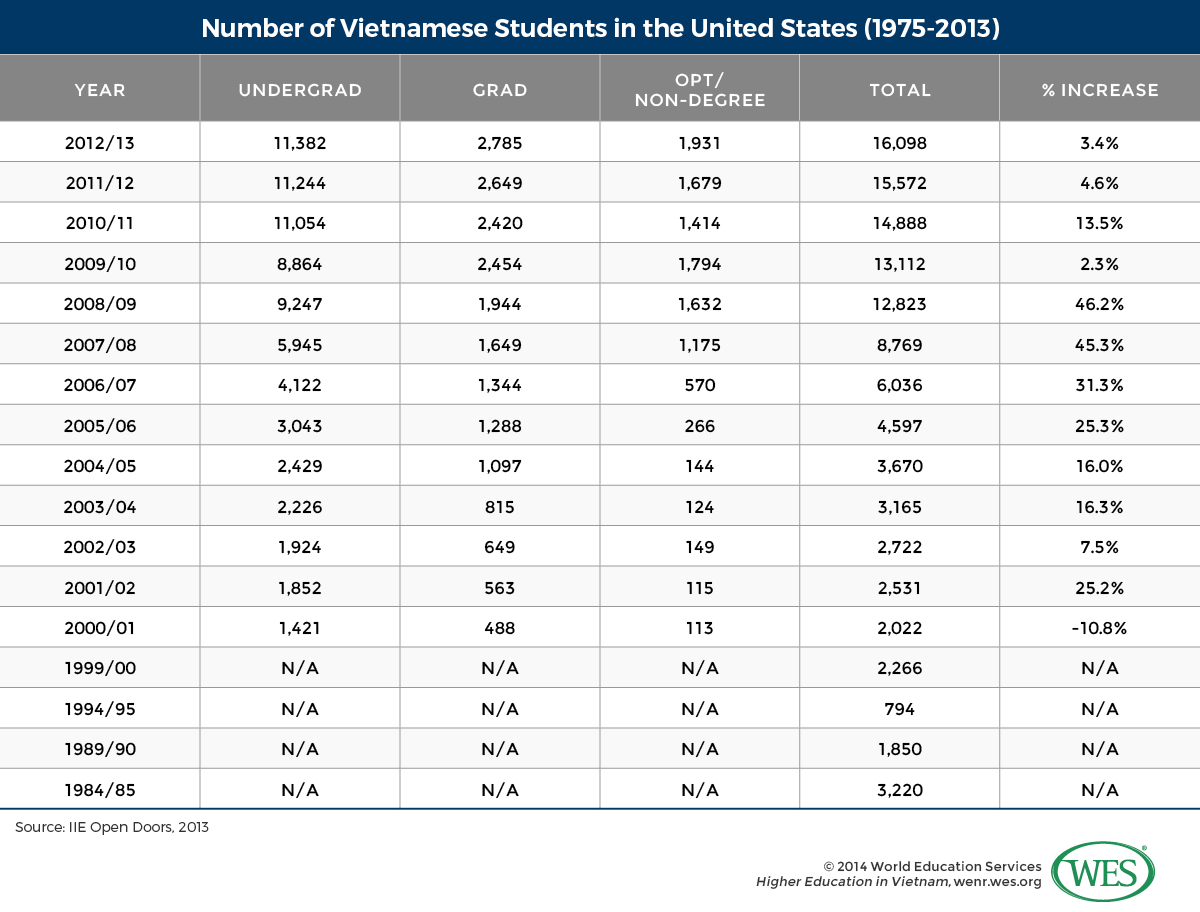

In the United States, according to the most recent data [6] from the Institute for International Education, there were 16,098 Vietnamese students on U.S. study visas in academic year 2012/13, making it the eighth largest sender [7] of tertiary students to the United States. This compares to just over 2,000 students in 2000/01, with especially significant increases seen in the years between 2005 and 2010 at a time when the Vietnamese economy and per capita income were booming.

Nearly 50 percent of Vietnamese students in U.S. higher education are studying either business or engineering, with business-related majors making up 38 percent of all enrollments in 2012/13.

It is currently estimated that 90 percent of Vietnam’s overseas student body is self-funded, ten times more than was the case at the turn of the century. And while per capita income has increased substantially in recent years, it was still just $1,755 last year, which is low even by regional standards. Not surprisingly, therefore, Vietnamese students are quite price sensitive, a fact not lost on regional recruiters from countries like China, Singapore and Taiwan who promote their institutions for their relative proximity and affordability.

Nonetheless, the United States is still seen as the gold standard among a majority of Vietnamese students looking at overseas study opportunities. According to the findings of a 2010 IIE Briefing Paper, based on 700 responses to a survey conducted in three major metropolitan areas among high school and university students, the U.S. is overwhelmingly considered by Vietnamese as their first-choice overseas study destination (first choice for 82 percent of those surveyed and second choice for 10 percent). However, the United States fared especially poorly in the perceived cost category of the survey (tuition and living expenses) when compared to regional alternatives and competitor English-language destinations.

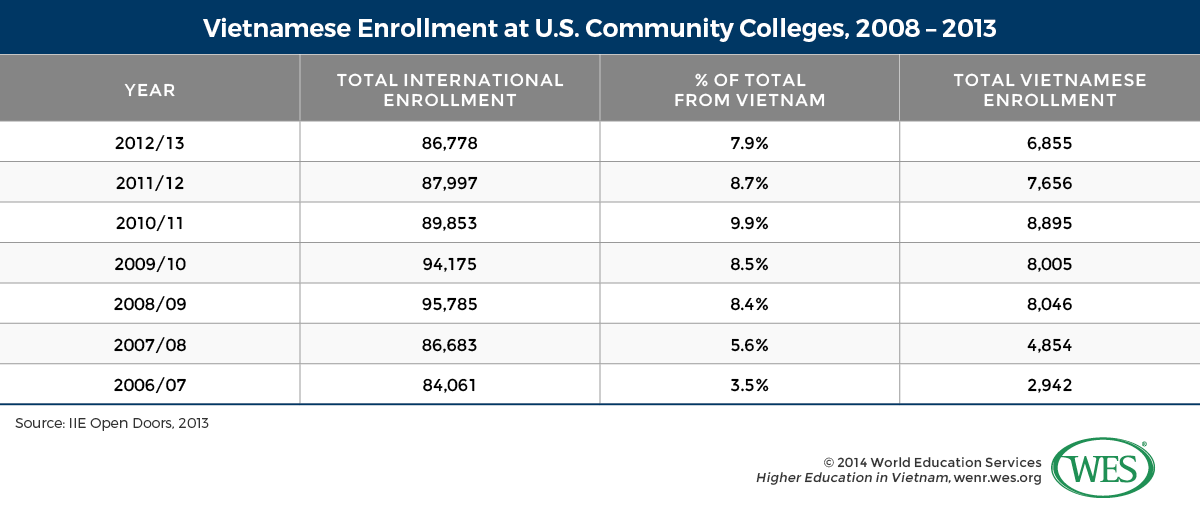

These two factors help explain the popularity of U.S. community colleges among Vietnamese students. Of the 16,098 Vietnamese students in the United States last year, 11,382 were studying at the undergraduate level (ranked sixth among all sending nations), with just 2,785 enrolled at the graduate level. Perhaps more significantly, of the 86,778 international students enrolled at America’s community colleges in 2012/13, 7.9 percent (6,855) were Vietnamese. This means that approximately 43 percent of all Vietnamese tertiary-level students in the United States last year were enrolled at a community college, making them the third-ranked nationality at U.S. two–year colleges behind just China and South Korea.

It should be noted here that 2013 community college enrollments among Vietnamese students represent a significant drop from 2011 when close to 9,000, or 60 percent of the U.S.-based student body was studying at that level.

Challenges Facing Vietnamese Higher Education

According to statistics from the Ministry of Education and Training, 1.8 million candidates registered for the 2012 centralized university entrance examination, of which 1.3 million applied to universities and 500,000 to colleges. Current capacity for incoming students at the nation’s 234 universities and 185 colleges is less than 600,000, meaning there is significantly more demand than can be met domestically.

Improving and widening domestic provision has been a recent priority of the Vietnamese government; however, a shortage of qualified teaching personnel has hampered those efforts. Recently, the government halted enrollment [10] in over 200 undergraduate programs at 71 universities and colleges due to a lack of qualified teaching staff. The government also stated last year that its tertiary massification efforts would be shelved for the near term due to the current oversupply of university graduates.

Although the number of university students has doubled since 1990, the number of teachers remains essentially unchanged. This is despite recent increases in budgetary allocations, liberalized private sector involvement, and the encouragement of foreign participation in education and training services. Foreign provision will not, however, solve the problem of under capacity or poor teaching standards.

According to a 2008 report [11] by researchers from Harvard’s Ash Institute at the Kennedy School, “foreign study is an important response to the crisis in Vietnamese higher education, but is by no means a solution. First and foremost, foreign study is only an option for the tiny minority who either have the ability to pay or are fortunate to win a scholarship. There is a wide and growing opportunity gap between urban and rural and between a wealthy elite and the great majority who remain poor. Vietnam is a large country and cannot possibly “outsource” higher education to foreign universities. Second, as long as Vietnamese universities continue to offer appalling working conditions and unattractive incentives, individuals who study abroad will continue to avoid university careers. Informal polls of Vietnamese graduate students in the US reveal that a strong majority will not return to existing Vietnamese universities but would consider returning if the professional environment were more attractive.”

Other issues raised by the Harvard report, Vietnamese Higher Education: Crisis and Response, center primarily on quality standards, especially as relates to research, autonomy and the connection between university programs and labor market needs. The report states that the higher education sector is deficient in all those areas and is producing an overabundance of university graduates with little to no job-ready skills.

The Harvard researchers highlight “the comparative lack of articles published by Vietnamese researchers in peer-reviewed international journals” and point to the fact that “the government was awarding research funding ‘uncompetitively’, and that there was a tremendous difference between what graduates had learned and what prospective employers wanted them to know.”

On job market relevance the report stated that, “Vietnamese universities are not producing the educated workforce that Vietnam’s economy and society demand. Surveys conducted by government-linked associations have found that as many as 50 percent of Vietnamese university graduates are unable to find jobs in their area of specialization, evidence that the disconnect between classroom and the needs of the market is large. With up to 25 percent of undergraduate curricula devoted to required coursework laden with political indoctrination, it is little wonder that Vietnamese students are ill-prepared for either professional life or graduate study abroad.”

This final point on overseas graduate study, the researchers posit, helps explain why Vietnamese enrollment in U.S. and European universities is so predominantly weighted towards the undergraduate level. In 2012/13, just 17 percent of Vietnamese students in the U.S. were studying at the graduate level. This compares to 43 percent among all sending countries.

In conclusion, the report states, “it is difficult to overstate the seriousness of the challenges confronting Vietnam in higher education. We believe without urgent and fundamental reform to the higher education system, Vietnam will fail to achieve its enormous potential.”

Education System

Since 1990, the Ministry of Education and Training [12] (MOET) has overseen nearly all aspects of the Vietnamese education system, including the regulation of new institutions, the creation of textbooks and curricula, decisions on admissions criteria, and the issuing of certificates and diplomas. Some specialist colleges are under the purview of other ministries, but the vast majority is governed by MOET.

The structure of the Vietnamese education system is similar to the United States in that it has 12 years of schooling followed by a four-year bachelor degree, a two-year master’s degree and a three- to four-year Ph.D.

Primary education is five years in duration (grades 1-5), and is followed by four years of lower secondary (6-9) and three years of upper secondary. The first five years are compulsory.

The language of instruction is Vietnamese, although a few universities are introducing English-taught programs and classes. The school year runs from September to June.

Admission to Higher Education

General Requirements

- Certificate of Secondary School Graduation (vocational or academic stream)

- Passing of the National University Entrance Examination

National University Entrance Examination

At the end of grade 12, students sit for a set of six examinations, which together constitute the testing for the upper secondary school leaving certificate. Administered in late May or early June and coordinated centrally by MOET, students are tested in a foreign language (typically English), mathematics, Vietnamese literature, and one of three other subjects. Each examination is worth 10 points and students must achieve a grade of at least five in each subject to pass and be awarded the Certificate of Secondary School Graduation (bằng tốt nghiệp trung học phổ thông).

Holders of the Certificate of Secondary School Graduation are eligible to take the National University Entrance Examination. Known locally as the ‘three commons,’ students take identical examinations across the country over the two-day testing period. Like the school leaving exam, the three commons is administered by MOET. Each institution sets its own entry scores for admission and students may apply to multiple institutions, typically three to four, before admissions standards are set.

The application process takes place in April with universities publishing their required standards as students prepare for the examination. Students make the decision on which university to have their exam marked at just before the exam date in early July. Top public universities receive the largest number of applicants, with lesser-known private universities receiving the fewest. Students who fail to gain admittance to their first choice institutions are allowed to apply to other universities in a second round in the autumn.

Typically, colleges have a cut-off mark of around 10 (out of 30), while universities set their scores at 13 or higher with top universities requiring around 20 points. Entry requirements for private universities tend to be lower than for public universities.

The examination is the only determinant of which school a student will attend and is therefore an incredibly high stakes affair in a country where many poor students see a university diploma from a well-regarded university as the only way to rise out of poverty and into the middle class. There had been plans to eliminate the exam by 2010, but those were abandoned, in part due to concerns over high school grade inflation and in-class cheating on school-administered tests. Officials now hope to make substantive changes to the system by 2020 in a bid to promote critical thinking over rote learning in high school, and also to curb the proliferating cram industry, by allowing institutions to select students based on school records. A select few institutions will reportedly be allowed to adopt their own admission systems for the 2014/15 cycle under a trial scheme. The centralized examination would be kept for some elite schools and programs after 2020, according to current plans.

Three examinations are administered in one of five groups depending on the major that the student wants to pursue:

- Group A: mathematics, physics and chemistry (for specialization in physics, engineering and computer science).

- Group B: mathematics, biology and chemistry (for specialization in medical and biological sciences).

- Group C: history, geography and literature (for specialization in humanities and social sciences).

- Group D: foreign languages, literature, mathematics (for specialization in foreign languages and foreign trade).

- Group E: mathematics, physics and another subject (for specialization in other fields).

Some students take multiple examinations if they are unsure of the major they wish to pursue.

Students with a three-year junior college diploma (bằng tốt nghiệp cao đẳng) can transfer to a bachelor’s degree program with advanced standing (up to two years).

It can take up to a year for the school leaving certificate to be issued, so students are initially awarded provisional certificates (giấy chứng nhận tốt nghiệp), allowing students to sit any necessary entrance examinations for higher education. The provisional certificate, which becomes redundant once the definitive certificate is issued, provides results from the final secondary examinations.

Junior College Admission

The bằng tốt nghiệp cao đẳng (Diploma of Secondary Vocational Education) grants access to higher education, with students primarily enrolling in junior colleges. Individual colleges may also administer an entrance examination.

Higher Education

Types of Institution

University-level higher education is offered at three main types of institution: multidisciplinary universities (Đại học), senior colleges with a narrower teaching focus (trường Đại học), and institutes (Học viện) which also tend to have a narrow disciplinary focus, but with a specialized research capacity.

The five biggest and most prestigious multidisciplinary universities are Vietnam National Unversity, Hanoi; Vietnam National University, Ho Chi Minh City; Hue University; University of Da Nang; and Thai Hguyen University. All were created in the 1990s through a series of mergers. They offer both undergraduate and graduate education.

Specialized institutions focus on one or two areas of study, including engineering, economics, law or foreign languages. Degree programs are offered at both the undergraduate and graduate levels.

In addition to public institutions of higher education, semi-public and entirely private universities are permitted to operate and charge tuition fees. Currently, the private sector accounts for 20 percent of schools and 15 percent of total enrollment at the tertiary level, according to 2012 government figures. Generally speaking, private higher education is perceived to be of a lower quality than that offered at public institutions.

Junior colleges (trường cao đẳng) and vocational training centers offer sub-degree programs. Associate’s degrees offered at junior colleges give advanced standing into degree programs or lead to employment. Shorter vocational certificate programs lead to employment only.

Most colleges are under the supervision of the relevant ministry, but an increasing number of private colleges are opening.

Currently, there are a total of 419 universities and colleges operating in Vietnam, with 185 university-level institutions and 234 colleges.

Vocational Qualifications

Typically, junior colleges offer vocational education with an academic focus, issuing Vocational Education Graduation Diplomas (bằng tốt nghiệp trung học chuyên nghiệp) and associate degrees (cử nhân cao đẳng – or – bằng tốt nghiệp cao đẳng). They can be specialized colleges, community colleges or teacher training colleges.

Diploma programs require one to two and a half years of full-time study after upper secondary school or three to four years after lower secondary school. Graduates may apply for admission to university.

Associates degrees require two to three and half years of full-time study – or 100 to 180 credits – at a junior college; most typically three years. Students must have completed secondary school and passed an admissions examination for entry. The curriculum tends to have a larger theoretical component than other vocational programs, but still retains a largely practical focus. Programs are divided into a general core curriculum and specialized training.

Lower level vocational training centers provide employment-focused trade programs of up to a year. There are no formal entry requirements and programs lead to the chứng chỉ nghề. At public schools, fess are subsidized by the relevant ministry, while at private centers costs are borne entirely by the student.

The Ministry of Labor, Invalids and Social Affairs [13] oversees the vocational training sector and issues the certificates and diplomas. The Ministry of Education and Training sets curriculum standards for all programs, while the ministry relevant to the area of training supervises individual colleges.

Graduates of junior college programs can earn advanced standing into bachelor degrees for up to two years in a similar major.

Universities (trường Đại học) and University Level Programs

Universities are either specialized or multidisciplinary. The two largest multidisciplinary universities were created in 1995 through a series of mergers. These are the Vietnam National University in Ho Chi Minh City and the Vietnam National University Hanoi. Other large regional universities created at around the same time include Hue University, Thai Nguyen University and Da Nang University.

Universities offer bachelor, professional, master and doctoral degrees. They are overseen by MOET, which also officially approves and signs conferred degrees.

The Vietnamese university system is heavily influenced by the Soviet academic system, in which universities were primarily teaching institutions, while research was carried out by research institutes. The Vietnamese government is attempting to promote university-based research, but these efforts have met with marginal success, according to observers.

Undergraduate

Undergraduate students can study via a number of different ‘modes,’ or delivery systems. This is clearly indicated on diploma and transcripts, and has implications for further study. These include: full-time (chính quy), which is the most competitive entry standard and most common mode of study; part-time (tại chức) for working adults, and with lower entry requirements; open admission (mở rộng) requiring fewer credits and again lower entry standards; shorter specialization (chuyên tu) programs for graduates to update or upgrade skills; and distance education (từ xa).

The bằng tốt nghiệp đại học is the first university degree and can be considered broadly equivalent to a bachelor degree. The diploma is typically issued with the title cử nhân followed by the area of specialization, such as khoa học (science), kinh tế (economics), or ngoại ngữ (foreign languages). Other titles include ký sự (engineer), bác sĩ (medicine), luật sư (lawyer), nha sĩ (dentist), or dược sĩ (pharmacist).

Programs require between four and six years of full-time study – or 180 to 320 credits – depending on the major. The undergraduate curriculum includes a general education component of three to four semesters – or 60-90 credits – and a specialized training component for the remainder of the program (four to eight semesters).

Graduate

Admission to master’s level bằng thạc sĩ programs is based on the bằng tốt nghiệp đại học (first university degree), which must be completed in full-time or in-service mode. Students must also pass a graduate school entrance exam.

Programs require between one and a half and two years of full-time study, or 40 credits, with a mix of coursework, research and a final dissertation. The final degree is awarded by the rector of the institution attended.

Doctoral

Students typically enter doctoral programs by invitation following a master’s degree, although exceptional students can also undertake combined master/doctoral programs upon graduation from the first university degree.

The bằng tiến sĩ (Ph.D.) requires a minimum of two years of coursework and completion of a thesis or research project. Integrated programs require four years of full-time study.

University Credit System

In the Vietnamese university system, one credit is equated to 15 hours of classroom instruction, 30-45 hours of practical training, or 45-60 hours of research and thesis writing. This is the system outlined by the Ministry of Education and Training; however, some institutions of higher education use their own credit system.

Grading Scale and Equivalency

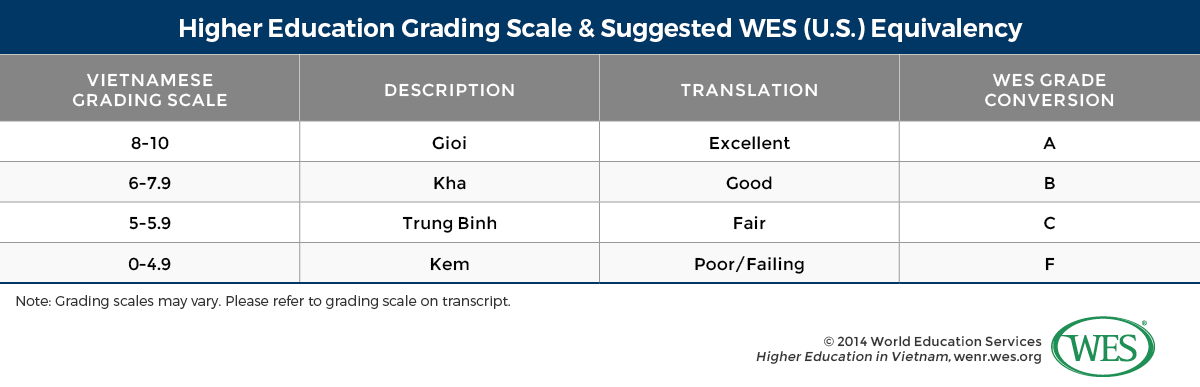

The following table shows the MOET-mandated grading scale for all education institutions, in place since 1993 and updated in 2006. We also provide the WES suggested equivalency.

WES Document Requirements

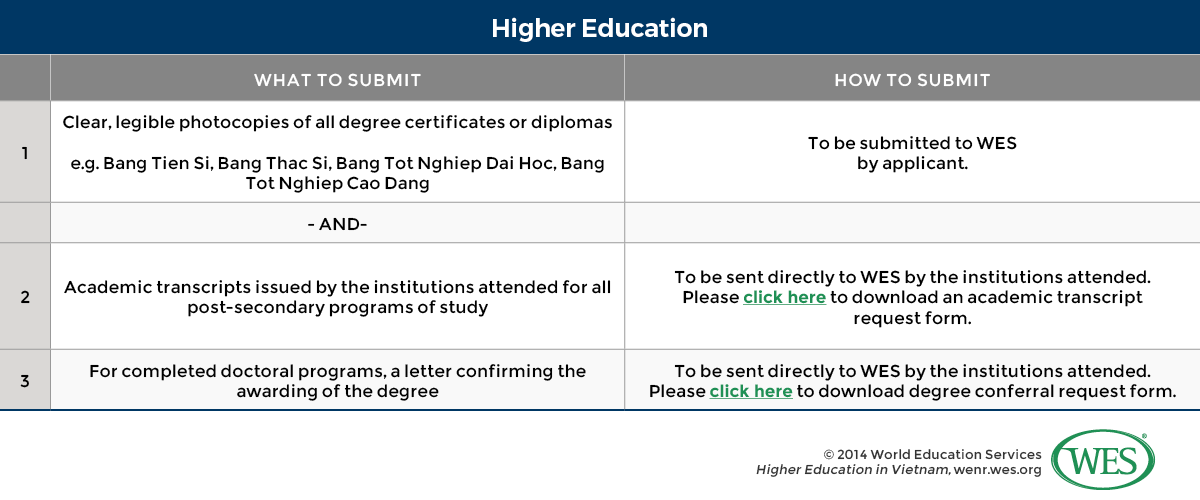

Higher Education: WES requires a photocopy of the degree certificates or diplomas to be submitted by the applicant. In addition, academic transcripts for all post-secondary programs must be sent directly to WES by the institutions attended. For completed doctoral programs, a letter confirming the awarding of the degree must be sent directly to WES by the institutions attended.

Sample Documents

This file of Sample Documents [16] (pdf) shows a set of annotated credentials from the Vietnamese education system:

- Certificate of High School Graduation (temporary, with translation)

- High School Transcripts (with translation)

- High School Degree Certificate

- Bachelor Degree Transcripts & Certificate

- Master Degree Transcript

- Master Degree Certificate