Education in Vietnam

Stefan Trines, Research Editor, WENR

A Surging Economy

Vietnam is a booming country that has seen sweeping market reforms since the 1980s, as the Communist government has moved from a command-style economic system to a more open capitalist system without relinquishing political control.

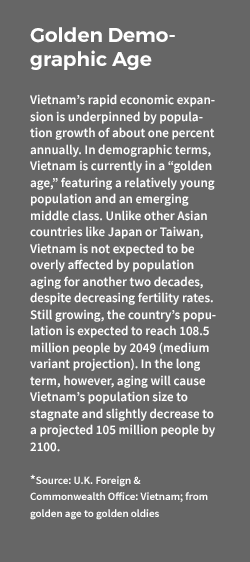

As in China, the success of this strategy has been remarkable: Over the past 30 years, Vietnam, a country of 92.7 million people (2016, World Bank), has transformed from an impoverished, war-ravaged country to a newly industrialized “tiger cub” with one of the most dynamic economies in the world. Between 1990 and 2016, Vietnam’s GDP grew by a whopping 3,303 percent, the second-fastest growth rate worldwide, only surpassed by China.

As in China, the success of this strategy has been remarkable: Over the past 30 years, Vietnam, a country of 92.7 million people (2016, World Bank), has transformed from an impoverished, war-ravaged country to a newly industrialized “tiger cub” with one of the most dynamic economies in the world. Between 1990 and 2016, Vietnam’s GDP grew by a whopping 3,303 percent, the second-fastest growth rate worldwide, only surpassed by China.

The country’s continued economic rise is not guaranteed and remains dependent on a variety of factors, including sustained levels of foreign direct investments, political stability, infrastructure development, and the modernization of a stifling regulatory system plagued by corruption.

Crucially, Vietnam needs to upskill its labor force, which is rapidly shifting with approximately 1 million agricultural workers transitioning into industry and services each year. Expanding access to education and vocational training are paramount objectives of the government. The number of students in higher education grew from around 133,000 students in 1987 to 2.12 million students by 2015. Despite its meteoric economic growth, Vietnam remains a relatively poor country with a per capita GDP of USD $2,186 – less than half of that of Thailand’s GDP, for example (2016, World Bank).

However, the economic outlook for Vietnam looks bright. The professional services firm Pricewaterhouse Coopers, for instance, recently forecast that Vietnam to continue to grow at a rapid pace over the coming decades, and become the world’s 20th largest economy by 2050.

Nominally still a Socialist Republic under Communist one-party rule, Vietnam is expected by many to eventually follow the development trajectory of Asia’s “tiger economies” (South Korea, Singapore, Taiwan and Hong Kong).

Education Reforms

One of Vietnam’s strategies to achieve further economic growth is the modernization of its education system, which is considered to be lagging behind other Southeast Asian countries by outside observers. Education features prominently in Vietnam’s current “socio-economic development strategy for 2011-2020”, which seeks to advance human capital development, boost enrollments in higher education, and modernize education to meet the needs of the country’s industrialization in a global environment. The goals of several of the current education reforms were already laid down in a government directive from 2005 on the “Comprehensive Reform of Higher Education in Vietnam, 2006–2020”.

Among the bold reforms currently enacted are the establishment of new accreditation and quality assurance mechanisms, the creation of a national qualifications framework, and a drastic increase in higher education enrollments by 125 percent, from 200 students per 10,000 people in 2010 to 450 students per 10,000 people by 2020.

- Teaching quality will be improved by requiring almost all higher education instructors to hold masters or doctoral degrees by 2020.

- Labor force development is being prioritized with large-scale investments in applied, employment-geared training.

- 70 to 80 percent of the student population should be enrolled in applied programs by 2020.

- The secondary education system is also undergoing major reforms, most notably with regards to high school graduation examinations and university admissions.

Another goal of the current reforms is the internationalization of Vietnam’s still somewhat insular higher education system. The government is trying to expand English-language education in Vietnam, and promote transnational cooperation and exchange with countries like Australia, France, the U.S., Japan, and Germany. Vietnam has also acceded to international education agreements, such as the Asia-Pacific Convention on the Recognition of Qualifications in Higher Education. Study abroad of Vietnamese students and scholars is explicitly promoted, while the government simultaneously seeks to increase the number of foreign students and researchers in Vietnam.

These fast-evolving developments have implications for international credential evaluation and student recruitment in Vietnam. To better understand these changes, this article describes current trends and developments in Vietnamese education and student mobility and provides an overview of the Vietnamese education system.

Outbound Student Mobility

Vietnam is currently one of the most dynamic outbound student markets worldwide, trailing mega sending countries like China and India only in sheer size. Between 1999 and 2016, the number of outbound Vietnamese degree students exploded by fully 680 percent, from 8,169 to 63,703 students (UNESCO Institute of Statistics). Outbound degree mobility in China, by comparison, grew by 549 percent during the same period, while the number of outbound Indian degree students increased by only 360 percent.

This drastic increase in Vietnamese mobility reflects the country’s swift economic growth, as well as of the shortcomings of its education system. Common outbound mobility drivers, such as an emerging middle class able to afford study abroad and rapid massification of education coupled with limited access to high-quality education, are prominent in the country. Vietnam has the fastest growing middle class in Southeast Asia, projected to grow to anywhere between 33 and 44 million people by 2020, depending on the estimate. Tertiary enrollments, meanwhile, tripled between 1999 and 2015. The number of youths seeking higher education in Vietnam has increased significantly, swelling the ranks of potential mobile students. Given Vietnam’s economic growth projections, student mobility is bound to increase in the years ahead, especially as the country seeks to internationalize its economy and education system.

Access and Quality Concerns

Access limitations and quality problems in Vietnam are also factors facilitating outbound mobility. Despite a growing number of new higher education institutions, Vietnam’s education system does not sufficiently absorb the burgeoning youth population of a country in which 37 percent of the population is below the age of 25. Vietnamese universities reportedly only had capacity for one-third of applicants in past years. Merely 6.7 percent of Vietnamese above the age of 25 held tertiary degree attainment in 2009, a considerably lower percentage than in other regional countries like Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and the Philippines.

Over the past decades, the fast-paced growth of the education system has intensified quality problems at overcrowded universities and led to the mushrooming of low-quality private providers. Harvard researchers Vallely and Wilkinson in 2008 described the Vietnamese education system as being in a state of crisis, characterized by international isolation, a lack of high-quality universities, inadequate foreign language training, bureaucratic obstacles, and curricula that do not prepare students for entry into the labor force. According to recent Vietnamese media reports, the majority of new university graduates are presently unable to find work, often due to a lack of skills.

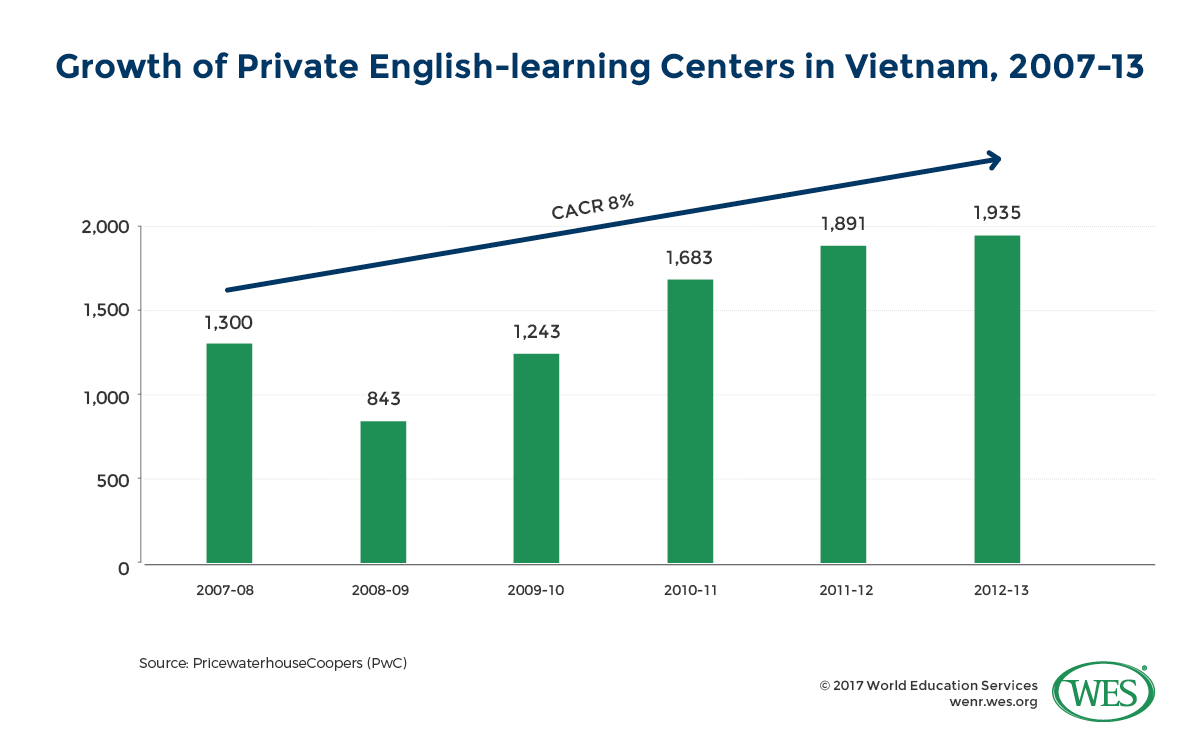

These shortcomings are likely to motivate aspiring Vietnamese students to seek education abroad. Another push factor is the country’s accelerating demand for English language education, which is, as of now, not sufficiently addressed by the overburdened Vietnamese system, even though the government in 2016 directed public universities to introduce English as a second language of instruction.

The government, now more keen to promote internationalization, recently expanded a number of scholarship programs. The so-called 911 project, launched in 2013, for instance, is slated to fund study abroad of 10,000 Ph.D. candidates until 2020 with up to USD $15,000 annually per student. Despite these increases in funding, however, the vast majority of Vietnamese outbound students were, as of recently, still self-funded. While scholarships awarded by the Vietnamese Ministry of Education were, as of 2016, predominantly given to students going to Russia, self-funded students prefer Western destinations. More than 60 percent of Vietnamese mobile degree-seeking students currently opt to study in English-speaking Western countries, according to the data provided by the UNESCO Institute of Statistics.

Study Destinations

The U.S. has, over the past decade, become the most popular destination choice among Vietnamese students enrolled in degree programs abroad, despite the high costs of study in the U.S. and the legacy of the Vietnam War. Fully 30 percent of outbound Vietnamese degree students (19,336) studied in the U.S. in 2015 (UIS).1 The Open Doors data of the Institute of International Education, which includes both degree and non-degree seeking students, shows that enrollments of Vietnamese students surged by a remarkable 1,009 percent between 2000/01 and 2016/17, making Vietnam at present the 6th largest sender of foreign students to the United States.

There are currently 22,438 Vietnamese students enrolled at U.S. institutions, predominantly at the undergraduate level. Many of them study at community colleges, where Vietnamese constitute the second largest group of foreign students, accounting for almost 10 percent of all international enrollments. Business majors are the preferred choice among Vietnamese students (30 percent of enrollments).

Surveys indicate that Vietnamese students consider the U.S. a “scientifically advanced country” with an “excellent higher education system” and a “wide range of schools and programs,” even though high costs remain a major concern for many students. Beyond that, student mobility to the U.S. also appears to be influenced by existing migrant networks – the largest numbers of Vietnamese students are enrolled at institutions in California and Texas, the two U.S. states with the highest concentration of Vietnamese immigrants.

The next most popular study destinations among Vietnamese degree students include Australia (13,147 students in 2015 as per the UIS), Japan (6,071 students in 2014) and France (5,284 students in 2015). With the exception of France, where enrollments remained relatively flat, the number of Vietnamese degree students in these countries has increased strongly in recent years, if at smaller growth rates than in the United States. In Australia, the number of students increased by 75 percent between 2009 and 2015, while in Japan the number grew 110 percent between 2009 and 2014. Canada also experienced strong growth – the number of Vietnamese students jumped by 203 percent between 2005 and 2015, according to the Canadian government.

It should be noted that the Japanese government reports vastly higher international student numbers (53,807 Vietnamese students in 2016) than the UIS and could, by some measures, be considered the primary study destination of Vietnamese students. But the Japanese statistics include a variety of different student categories in non-degree programs, including students enrolled in language training institutes and university-prep programs. The number of tertiary students is much smaller: 25,228 Vietnamese students studied at Japanese language training institutes, for instance.

Inbound Mobility

Vietnam is currently not a major destination country for international students. To attract more foreign students and researchers, the government has removed some obstacles, for instance, by allowing universities to set their admission standards for international students, instead of requiring Vietnamese-language entrance examinations. That said, Vietnam’s lack of top quality universities and few English-taught programs mean that Vietnam is not an obvious destination choice for international students beyond students studying Vietnamese culture and language. The largest numbers of foreign degree students in Vietnam presently come from neighboring Laos (1,772 students) and Cambodia (318 students). (2016, UIS). Both countries have sizeable Vietnamese-speaking minorities.

Transnational Education (TNE)

TNE in Vietnam is growing, even though very few reputable foreign institutions have established actual branch campuses in the country so far. Australia’s RMIT University is among the few foreign-owned universities in Vietnam. Other foreign-backed universities include the Vietnamese-German University, Vietnam-Japan University, and the Fulbright University Vietnam, a non-profit university recently set up by Harvard University.

At the program level, the number of government-approved TNE programs has increased significantly in recent years growing by 45 percent between 2010 and 2011 alone, with universities from countries like France, the UK, and Australia being the main partners in twinning agreements and transnational degree programs. Also of note is that the French accreditation agency HCERES in 2017 granted accreditation to four Vietnamese public universities.

TNE in Vietnam continues to face some challenges, including quality problems, high taxation, lengthy approval processes and a difficult regulatory environment in which the Communist party seeks to maintain control over foreign institutions, while simultaneously trying to attract more foreign providers to Vietnam. In recent years, growing numbers of questionable foreign schools and diploma mills started to proliferate in the country.2 In response, the Vietnamese government in 2012 imposed restrictions on foreign institutions, such as a minimum initial investment volume of USD $15 million for higher education institutions, minimum tuition fees of USD $7,500 per annum, and enrollment caps that limited the number of Vietnamese students at foreign high schools to 20 percent of the student body.

In 2017, the government further tightened these restrictions and required foreign institutions to front a minimum investment of USD $45 million. Enrollment caps for elementary and secondary providers, on the other hand, are currently slated to be removed – a development expected to lead to a significant increase in the number of international high schools in Vietnam, especially since demand for foreign-language schooling is booming.

In Brief: Vietnam’s Education System

Administration of the Education System

Until the 1980s, Vietnam’s education system was modeled after the system of the Soviet Union. Economic liberalization policies enacted after the 1986 Đổi mới reforms have since led to far-reaching changes in various sectors, including the education system, but the country remains under the firm control of the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV). Many aspects of the education system, thus, are highly centralized and directed by the Ministry of Education and Training (MOET) in Hanoi.

The MOET is responsible for most aspects of schooling and the implementation of education policy. Until recently, the ministry exercised far-reaching control over higher education institutions; a fact often cited as a hindrance for the modernization of education in Vietnam. The MOET stipulated rigid curricula and textbooks, admissions guidelines and staffing. Curricula, for example, continued to include mandatory Marxist-Leninist content, said to be of little practical relevance in the labor market

However, the government has in recent years scaled back various regulations, and plans to increase the autonomy of higher education institutions (HEIs) “in terms of training, scientific research, organization, personnel, finance and international cooperation.” The government has recently granted HEIs increased autonomy to determine their curricula and admissions quotas. Despite these changes, observers have noted that the system so far continues to be characterized by a high degree of bureaucratic centralization and a tendency to retain socialist curricula, even atVietnam’s privileged National Universities, which technically already had greater autonomy than other institutions since their inception in 1993.

In addition to universities overseen by the MOET, a sizeable number of public institutions are under the purview of other government bodies, such as people’s committees and different line ministries overseeing specialized institutions. Since 1998, large parts of vocational education and training are overseen by the Ministry of Labor, Invalids and Social Affairs (MOLISA).

Education Funding

Vietnam has ramped up education spending significantly in recent years. Education expenditures as a percentage of GDP increased from 3.57 percent in 2000 to 5.18 percent in 2006, and have since then remained above 5 percent, reaching 5.7 percent in 2013. Education spending as a percentage of the government budget has also been growing. Education is the largest expenditure item on the state budget and stood at 20 percent of total government expenditures in 2015 (USD $10 billion), a far higher percentage than the global average of 14.1 percent (2013).

Increased funding notwithstanding, public schooling in nominally Socialist Vietnam is not entirely free and getting increasingly expensive. Even though elementary education is officially provided free of charge and the government covers most costs, elementary schools charge a variety of supplementary fees, ranging from maintenance levies to fees for the acquisition of books and uniforms. Secondary public schools, meanwhile, are allowed to charge small tuition fees. In addition, it is not uncommon for parents to pay school teachers for extra private lessons to ensure the academic success of their children – an often corrupt practice that increases costs and inequalities in public education.

Increased funding notwithstanding, public schooling in nominally Socialist Vietnam is not entirely free and getting increasingly expensive. Even though elementary education is officially provided free of charge and the government covers most costs, elementary schools charge a variety of supplementary fees, ranging from maintenance levies to fees for the acquisition of books and uniforms. Secondary public schools, meanwhile, are allowed to charge small tuition fees. In addition, it is not uncommon for parents to pay school teachers for extra private lessons to ensure the academic success of their children – an often corrupt practice that increases costs and inequalities in public education.

In higher education, tuition fees averaged between USD $262 and USD $385 annually in 2015/16, but are bound to increase. Several public universities have already been exempted from caps on tuition. Top universities like the Ho Chi Minh City University of Technology are currently charging annual tuition fees of USD $ 1,000 for bachelor’s programs.

To ease the financial burden on the state and modernize the education system, the government also seeks to advance the privatization of education, an objective that could further drive up costs for students. The goal is to increase the share of private funding sources at public universities and ensure that up to 40 percent of the student population will be enrolled at private institutions by 2020.

Enrollments and Progress in Elementary and Secondary Education

According to the General Statistics Office of Vietnam, about 7.8 million elementary pupils, 5.14 million lower-secondary students, and 2.4 million upper-secondary students were enrolled at 15,254 elementary schools, 10,321 lower-secondary schools, 2,399 upper-secondary schools, and 986 mixed schools throughout Vietnam in 2015/16.

Increased funding for education and other reform measures have led to tremendous improvements in enrollment rates and educational quality. At the elementary level, for instance, great progress has been made in closing gaps between urban centers and rural regions – the net elementary intake rate in rural regions like the Central Highlands and the Mekong Delta increased from 58 and 80 percent in 2000/01 to 99 and 94 percent in 2012/2013. Repetition and drop-out rates fell significantly throughout the country.

The net intake rate for lower-secondary education increased from 69.5 percent in 2000/01 to 92 percent in 2012/13 nationwide, despite lingering disparities between rural and urban regions at the secondary level. Other achievements include significant improvements in student-teacher ratios and an increase of youth literacy from 93 percent in 2002 to 97 percent in 2012. The upper-secondary school graduation rate stood at 95 percent in 2015/16.

Underscoring recent improvements in educational quality at the secondary level, Vietnam ranked 17th out of 65 countries, ahead of Western countries like Australia, the U.S., or France, when for the first time it participated in the OECD PISA study in 2012. Some observers have argued that the remarkably good results do not truly reflect educational quality in Vietnam and may be the outcome of the test’s emphasis on mathematics and its standardized testing format. Others contend that Vietnam’s success is based on smart curricular design and should serve as a model for lower-ranked ASEAN countries like Malaysia, Indonesia, and Thailand.

Elementary Education

Elementary education(tiểu học) in Vietnam begins at the age of six and lasts five years (grades 1-5, until age 11). Subjects taught include Vietnamese, mathematics, moral education, natural and social sciences, arts, and physical education, as well as history and geography in grades four and five. In 2017, the MOET announced that it would introduce foreign language and computer training starting in grade three, and also offer minority languages as an elective subject.

The curriculum emphasizes rote memorization and the language of instruction is Vietnamese. Textbook learning increases in higher grades. Promotion is based on continuous assessment and year-end exams. A final exit examination used to be required until the 2000s but has since been abolished.

Until 2005, compulsory education in Vietnam ended with the completion of elementary education at the age of eleven (grade 5) – an early age by international standards. Vietnam’s education law of 2005 since stipulates universal and compulsory education until grade 9, but that objective has of yet not been achieved. Current reforms seek to universalize lower-secondary education by the end of the decade and implement compulsory education until age 15 (grade 9) throughout the country, beginning in 2020.

Lower Secondary Education

After completion of grade 5, pupils can continue their education in a four-year lower-secondary education cycle (trung học cơ sở) or enroll in short-term vocational training programs.

Admission to general lower-secondary education is open to all pupils who have completed elementary education. It lasts from grade six to grade nine and concludes with the award of a Lower Secondary Education Graduation Diploma (Bằng tốt nghiệp trung học cơ sở).

The curriculum includes Vietnamese, foreign language, mathematics, natural sciences, civics, history, geography, technology, computer science, arts, and physical education. A second foreign language and minority languages are offered as elective subjects. Students attend up to 30 45-minute classes per week, and annual promotion is based on teacher assessment and examinations. A final intermediate graduation examination used to be required for completing the program but is no longer in use since 2006.

General Upper-Secondary Education

Access to non-compulsory upper-secondary education is competitive and examination-based. The MOET has in recent years adopted various measures to streamline entrance and graduation examinations, and the system is currently undergoing frequent changes. Voluntary supplementary exams to gain “priority admission” at upper-secondary schools, for instance, were suspended in 2016.

Entry into public upper-secondary education nevertheless depends on rigorous entrance examinations. Competition is particularly fierce for coveted spots at prestigious “high schools for the gifted,” which only admit the very best students. Other highly selective institutions include specialized high schools that offer programs focused on subjects like foreign languages.

Students who do not score high enough in the entrance exams to be admitted into upper secondary schools in the general track may seek admission to vocational upper-secondary programs (discussed below) or have to attend expensive private schools.

General secondary education encompasses grades 10 to 12 (ages 15-18) and concludes with the award of the Secondary Education Graduation Diploma (Bằng Tốt Nghiệp Phổ Thông Trung Học). Programs are usually offered in three different streams or subject groups (technology, natural science, and social sciences and foreign languages).

All course requirements in specialization subjects used to be stipulated by the MOET and involved a total of 6 hours per week in mathematics, physics, chemistry, and biology in the natural science track; and literature, history, geography, and foreign languages in the social sciences and foreign language track. Current reforms, announced in 2017, however, will allow for greater individual customization with elective concentration subjects now making up one-third of the curriculum. Beyond concentration subjects, all students take a core curriculum that includes subjects ranging from Vietnamese to foreign language (mostly English), mathematics, and physical and military education.

Upper-secondary students attend up to 30 45-minute classes per week. Promotion is based on teacher assessment and year-end exams. Students who fail the annual examinations twice have to repeat the year. High school graduation requires passing a rigorous final secondary school graduation examination, which is also used to determine admission to higher education (see section on university admission below for more details).

Vocational Education and Training

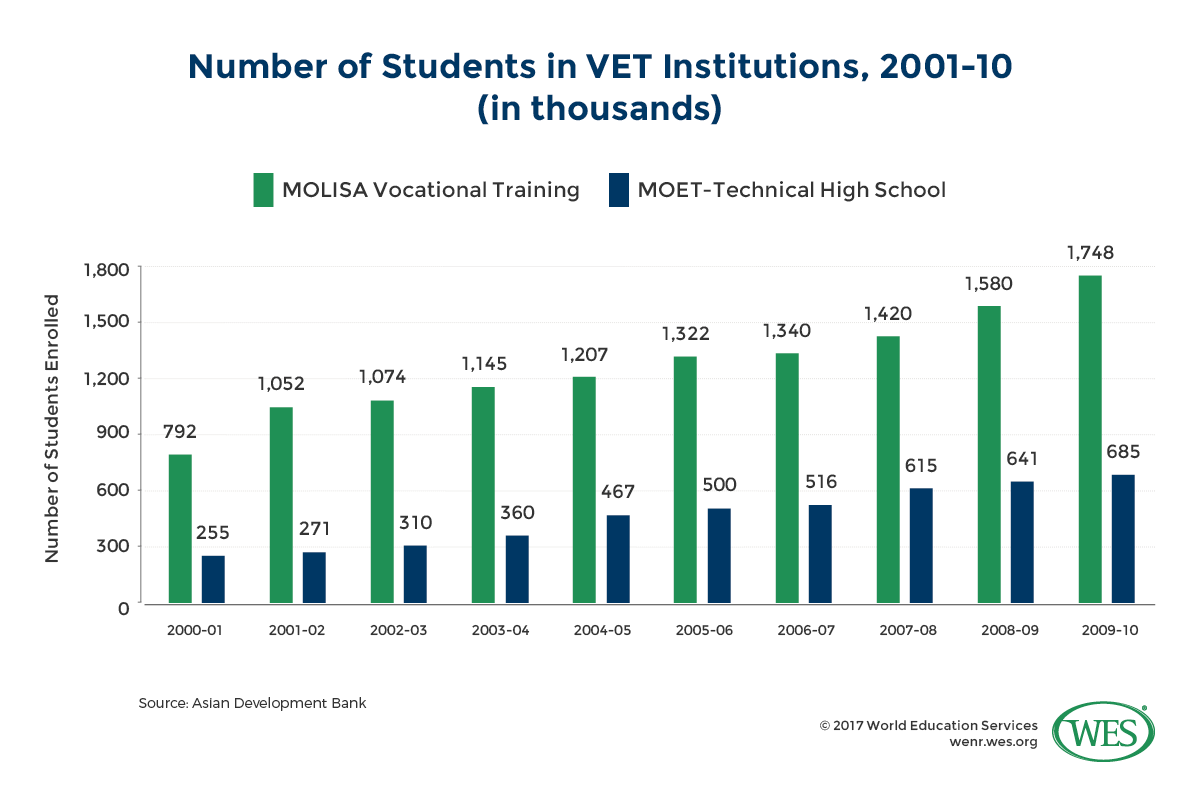

Several options for vocational education and training (VET) exist in Vietnam. Both the MOET and MOLISA oversee a variety of VET programs, ranging from short-term continuing education programs to formal training programs at both the secondary and post-secondary levels. Short-term vocational certificate programs (ngắn hạn) offered at vocational training centers are open to elementary school graduates, whereas longer programs (up to three years) offered at vocational schools typically require completion of at least lower-secondary education for admission. These longer programs lead to the award of a Vocational Training Diploma (Bằng Tốt nghiệp Nghề) – a credential that qualifies for employment in a number of trades.

Lower secondary graduates can also enroll in more academically oriented vocational/technical high school programs, referred to as professional secondary or intermediate professional education, that combine vocational training with general education. These programs lead to the award of a Professional Secondary Education Graduation Diploma (Bằng Tốt nghiệp Trung học Chuyên nghiệp), last three to four years, and usually require passing an entrance examination. Passing of the final national secondary school graduation examination upon completion of the program gives access to university education, but most students in the vocational track continue their studies at junior colleges. Students who already hold a general secondary education diploma can earn a professional secondary diploma in shortened one to two-year programs.3

At the post-secondary level, VET is typically provided at junior colleges (Cao đẳng), although college-level programs are also increasingly offered by universities. Programs last between two and three and a half years and lead to the award of an Associate degree (Cử nhân Cao đẳng), or a Junior College Graduation Diploma (BBằng Tốt Nghiệp Cao Đẳng). Programs are geared towards employment and include a practical training component of up to 30 percent. Fields of study include business administration, banking, accounting, tourism, information technology, or health care. Admission is based on the upper-secondary school graduation examination.

Vietnam’s Quest for Vocational Education and Training (VET)

Vietnam is in urgent need of skilled labor – a shortage that is fueled by the country’s rapid economic growth and the increasing presence of foreign companies. Vietnam’s labor force composition has changed drastically in recent years. Employment in the agricultural sector dropped from 69 percent in 1997 to 48 percent in 2011 with about 1 million workers transitioning from agriculture to industry and service sectors annually as of 2014. The majority of the country’s workforce, however, is presently lacking sufficient skills and technical expertise in a variety of fields, ranging from information and communications technology to banking, accounting, tourism or health care. Fully 83 percent of Vietnam’s labor force was still unskilled in 2012, and the country’s labor productivity (an indicator of human capital development) was 37 percent of that of Thailand and 23.3 percent of that of Malaysia in 2010, according to the OECD.

Vietnam’s government has, thus, made human capital development a top priority and seeks to catch up with other countries in the ASEAN community. It has allocated increased funds to VET and pushed the creation of new vocational training institutions, the number of which expanded to 165 vocational colleges, 301 vocational secondary schools, 874 vocational training centers and various other training programs under the supervision of MOLISA by 2014. The government has also sought assistance from countries and institutions like Australia, Germany, Korea, Japan, the EU and the Asian Development Bank in building a modernized VET system. It intends to boost the percentage of workers that have undergone formal vocational training to 60 to 65 percent of the workforce by 2020 while expanding enrollments in career-oriented study programs to 70 to 80 percent of all students in Vietnam.

Vietnam’s quest for vocational training is also driven by increased demand for VET among Vietnam’s youth. Poor employment prospects for university graduates, in particular, have caused growing numbers of high school graduates to opt for vocational education instead of pursuing an academic career. As the online newspaper VietNamNet has noted, even university graduates increasingly opt to put their “… bachelor’s degree into a drawer and go back to vocational school because industrial zones and factories only need skilled workers, not bachelor degree graduates”. Between 2000/01 and 2009/10 alone, the number of students enrolled in vocational training schools and professional secondary programs increased by 132 percent.

Admission to Higher Education

Progression from secondary to higher education in Vietnam is highly competitive and based on demanding examinations that place great pressure on students, similar to the examination system in China. Examination periods have been dubbed “suicide season,” due to increasing numbers of student suicides after the announcement of university entrance examinations each summer. In 2012, only 30 percent of test takers passed the entrance exams, according to VietNamNet.

These examination pressures are one of several reasons that caused the Vietnamese government to enact many sweeping and ongoing reforms in university admissions. Until 2015, students first sat for a secondary school graduation examination in May/June, and a subsequent national university entrance examination in July (the so-called “three commons” exam). Since 2015, the university entrance exam has been abolished and merged with the secondary graduation exam into a single national secondary school graduation exam (Kỳ thi trung học phổ thông quốc gia), now used to determine university admission. The change was intended to simplify the strenuous admissions process and lower the costs for universities, as well as students, many of whom were relying on expensive prep-schools to prepare for the university entrance exams. More students in rural regions can now also take the test locally, instead of having to travel to Hanoi or Saigon to sit for entrance examinations.

The structure and content of the new examination has undergone some changes since it was first announced. The most recent format (2017) of the “2-in-1” national graduation exam includes five test subjects: Three compulsory subjects (mathematics, Vietnamese language, and foreign language) and two stream-specific combination subjects, which include natural sciences (physics, chemistry, biology) and social sciences (history, geography and civics). Students who intend to apply for university take exams in four subjects, but can also choose to sit for a fifth subject to increase options for admission. Students who do not wish to move on to university can opt to graduate with three test subjects.

The examinations take place in June or July, are administered by the provincial Departments of Education, and involve multiple choice and essay questions. The minimum passing score in each subject is 5 out of 10. Universities typically base admission on the cumulative score in three subjects they consider relevant for the chosen major. The higher the test scores, the better the chances of admission into first-choice institutions (students can apply to multiple schools). The minimum threshold for university admission set by the MOET is a cumulative score of 15 out of 30 in three subjects, but requirements vary by institution and are often much higher, with prestigious universities only accepting students with a score of 29 or higher. Junior Colleges usually have lower score requirements than universities (the official minimum threshold score is 12).

The government intends to lessen the importance of examinations and has announced that national graduation exams will, in fact, be abolished altogether after 2020, at which point admission will be based on overall student performance during senior high school, rather than one final high stakes examination. The content of the final examinations will be incorporated into the high school curriculum. Given the frequent changes in university admissions in recent years, it remains to be seen, however, if and when these changes will be realized.

It should also be noted that the MOET has given public universities the freedom to determine their admission requirements beyond graduation exam results. Some large and prestigious universities, including the Vietnam National University (Hanoi) or the Foreign Trade University, for example, now utilize independent entrance examinations. Since average scores and pass rates in the national graduation exams held in 2017 were much higher than in previous years, growing numbers of universities may start using their own, more selective admissions tests.

Higher Education Institutions

Types

The types of HEIs in Vietnam include junior colleges (trường cao đẳng – community colleges, teacher training and other specialized colleges), mono-specialized universities (đại học đơn ngành), multi-disciplinary universities (đại học đa ngành), and postgraduate research institutes (học viện). According to Vietnam’s 2005 Higher Education Law, HEIs are public, private, or people-founded (tuition-funded institutions run by nongovernmental organizations like trade unions, cooperatives or youth organizations). There are also two public Open Universities (HCMC Open University and Hanoi Open University), which offer programs for students who scored too low in the high school exams to be admitted to regular universities. Open programs (mộ rồng) may also be offered at other universities.

Largest Universities, Rankings, and Research

The two biggest university systems in Vietnam are the Vietnam National University, HCMC and Vietnam National University, Hanoi – both public institutions with multiple mono-disciplinary member universities. VNU in Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC), the country’s largest city, has a total enrollment of approximately 61,500 full-time students and offers at least 120 bachelor’s programs, as well as a large variety of master’s and doctoral programs. VNU-Hanoi is smaller with about 34,000 students, according to the MOET. It reportedly has an acceptance rate of about 30 percent and charges tuition fees of USD $1,000 annually for bachelor’s programs.

A recent non-governmental Vietnamese university ranking declared VNU Hanoi, Ton Duc Thang University and the Vietnam National University of Agriculture as the best universities in the country, but has been heavily criticized for its methodology. No Vietnamese universities are included among the world’s top 1,000 in the most common world university rankings. The Vietnamese government is trying to change that and has selected three universities, the Vietnamese-German University, the Hanoi University of Science and Technology, and the Vietnam-Japan University, to be developed into world-class research universities.

Academic Research in Vietnam is still predominantly undertaken at research institutes (a legacy of the old Soviet-based system). Universities have since 1998 been allowed to offer postgraduate programs, but the academic research sector remains, as of now, relatively underdeveloped and underfunded by international comparison. The output of research publications by Vietnamese scholars, for instance, is far below the output of other regional countries like Thailand. Student enrollment in advanced study programs is still relatively small if growing briskly. While there were only 30,683 master’s students and 2,505 Ph.D. candidates nationwide in 2009, the latest statistics publicized by the MOET show that this number has jumped to 105,801 master’s students (6 percent of all enrollments) and 15,112 doctoral students (0.85 percent of enrollments) in 2017. In Thailand, by comparison, master’s and doctoral students accounted for 8.5 percent and 1.1 of all enrollments in 2016. MOET officials in 2016 expressed concerns that this rapid growth has been achieved at the expense of quality and led to an “inflation” of inadequately trained Ph.D.s.

Rapid Growth and Staffing Problems

Vietnam’s university system has expanded dramatically over the past decades – from 101 public HEIs, zero private institutions, and 133,000 students in 1987 to 357 public universities and colleges, 88 private HEIs and approximately 2.12 million students in 2015.

This swift massification has over the past decades resulted in overcrowded universities and inadequate teacher to student ratios, but the situation has improved somewhat in recent years. In the public sector, growth in enrollments has recently slowed, and the number of students has, in fact, decreased from about 2 million in 2014 to 1.85 million in 2015, likely due to a shift in enrollments towards the non-tertiary VET sector. Between 2005 and 2014, faculty growth in the higher education sector has also outpaced student enrollments –teaching staff at HEIs increased by 88 percent compared to a 70 percent increase in students.

According to statistics published by the General Statistics Office of Vietnam, the student to teacher ratio in higher education has improved noticeably in recent years and stood at 1 to 22.7 in 2015. The official goal is to decrease this ratio to 1:20 by 2020. Between 2016 and 2017, the number of instructors at public HEIs increased by 4.6 percent. But it remains to be seen how the goal of decreasing student to teacher ratios can be aligned with the government’s simultaneous goal to more than double student enrollments from 2 percent of the population in 2010 to 4.5 percent of the population in 2020. Thus far, these enrollment goals remain a work in progress, despite rapid massification. Students accounted for roughly 2.6 percent of the population in 2014.4

Another issue is the quality of teaching in Vietnam. In 2009, less than half of teaching staff in higher education held graduate degrees. The situation has since improved. In 2012, 46 percent of instructors held master’s degree, and 14 percent held doctoral degrees. However, Vietnamese universities are currently struggling to recruit qualified instructors, particularly those holding Ph.D. degrees. The government plans to increase the number of instructors with master’s and doctoral degrees to 60 and 35 percent of all teaching staff, respectively, by 2020. But the current shortage of teachers may slow down the achievement of this goal. Lecturers in Vietnam tend to be poorly paid, and holders of doctoral degrees often have more lucrative employment opportunities in other fields.

Private Institutions

The first non-state HEI in Vietnam, Thang Long University in Hanoi, opened in 1988. Due to the sensitive political nature of privatization in Communist Vietnam, non-state HEIs were at first limited to people-founded and semi-public institutions (tuition-funded institutions under state control). Private for-profit HEIs were not allowed to operate until 2005. Since that change, the number of private institutions has expanded quickly and reached 88 private HEIs as of 2015. Despite this growth, however, total enrollments in the private sector stood at only about 13 percent in 2015 (down from 15 percent in 2010), according to government statistics. This is significantly below the government’s target of 40 percent by 2020.

Many of Vietnam’s private HEIs are profit-driven “demand-absorbing institutions,” that is, institutions that provide access to higher education, but not at the same level of academic quality or rigor offered by most public institutions. Private institutions are often expensive and presently cannot effectively compete with the much more popular top-tier public universities. Many private HEIs concentrate on niche fields and areas where public universities fail to meet growing demand (business administration, foreign languages and computer and information technology). In 2012, enrollment levels at private HEIs were so critical that the Vietnam Private Universities Association issued a petition urging the prime minister to allow private universities to lower their admission standards to recruit more students.

Academic Corruption in Vietnam

Vietnam is a fairly corrupt country by international standards. It was ranked the 33rd most corrupt country out of 176 countries included in Transparency International’s (TI) 2016 Global Corruption Perceptions Index. Breakneck economic transformation, a lack of political accountability, red tape and a large-sized, poorly paid state bureaucracy are among the factors that facilitate corruption in Vietnam. The U.S. Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor noted in 2016 that corruption “continued to be a major problem” and that “nepotism and bribery in the public sector were prevalent throughout the country,” while “nearly half (46 percent) of foreign companies cited corruption as their greatest challenge”.

Education is considered the second most corrupt sector in Vietnam after the police. Bribery to ensure university admission or grade improvements is common due to underpaid educators being susceptible to corruption. Fully 61 percent of Vietnamese respondents surveyed by TI confirmed that parents pay bribes to teachers or school administrators. Some reported bribes were as high as USD $3,000 even for admission to desirable elementary schools.5

Other widely reported problems include plagiarism in higher education, the fraudulent acquisition of academic degrees, manipulated budget estimates and the ‘leakage’ of funds from public procurement projects (teaching materials and construction of facilities, etc.).

These forms of corruption tend to erode educational quality and hold back economic development. Rampant corruption is also political legitimacy problem for the CPV. The government has in recent years enacted various policy measures to combat corruption and made some high profile arrests, at least one of which resulted in the death penalty. It remains to be seen, however, how effective these measures will be in curbing the endemic levels of corruption in Vietnam.

Quality Assurance: The New Accreditation System

One of the reforms currently enacted in higher education is the implementation of new quality assurance mechanisms for HEIs. In 2004, the MOET initiated a new accreditation process based on institutional self-assessments and internal quality assurance mechanisms that are externally evaluated by accreditation agencies. Four years later, a National Accreditation Council was established under the MOET. By 2009, 110 Vietnamese universities had established internal quality assurance centers, and 20 universities had received accreditation.

The process has since undergone various changes. At present, accreditation is conducted by four accreditation centers under the guidance of the MOET’s General Department of Education Testing and Accreditation (GDETA). They are the Center for Education Accreditation – VNU-Hanoi, the Center for Education Accreditation – VNU-HCMC, the Center for Education Accreditation – Da Nang University, and the Center for Education Accreditation of the Association of Vietnam Universities and Colleges. These four agencies are tasked with accrediting HEIs, as well as vocational schools in the VET sector. Assessment criteria include a clear mission statement and adequate resources, staffing and curricula to realize this mission and prepare graduates for employment, as well as compliance with state regulations on international collaborations, and commitment to the socio-economic development of local communities and Vietnam. (For a sample of a self-assessment report, see the report of Tan Tao University, submitted in 2016).

Accreditation is granted for five-year periods and is mandatory for all HEIs in Vietnam. Due to a lack of resources and staff, progress in accreditation, however, has thus far been sluggish, even though more than 90 percent of Vietnamese institutions have established internal quality assurance centers. In March 2017, the MOET promised that 35 percent of universities and 10 percent of junior colleges would be evaluated and accredited until the end of the year. Program accreditation has also been introduced but is still relatively uncommon as of 2017.

Other Reforms: New Credit System and Grading Scale

There have been several other changes in higher education over the past decade. In 2007, the MOET introduced a new U.S.-style credit system at HEIs that gives students greater freedom to structure their curricula. Whereas students under the previous system stayed together as a group and followed the same pre-set curriculum throughout the program, they since can choose more freely between credit-based courses. The new curricula include mandatory and elective courses worth 2 to 4 credits. One credit represents at least 50 minutes of in-classroom study and 100 minutes of homework, taken over a 15-week semester. 30 credits represent one year of study at the undergraduate level. Most programs at Vietnamese universities are taken over two semesters per year (commonly from September to January and from February to June).

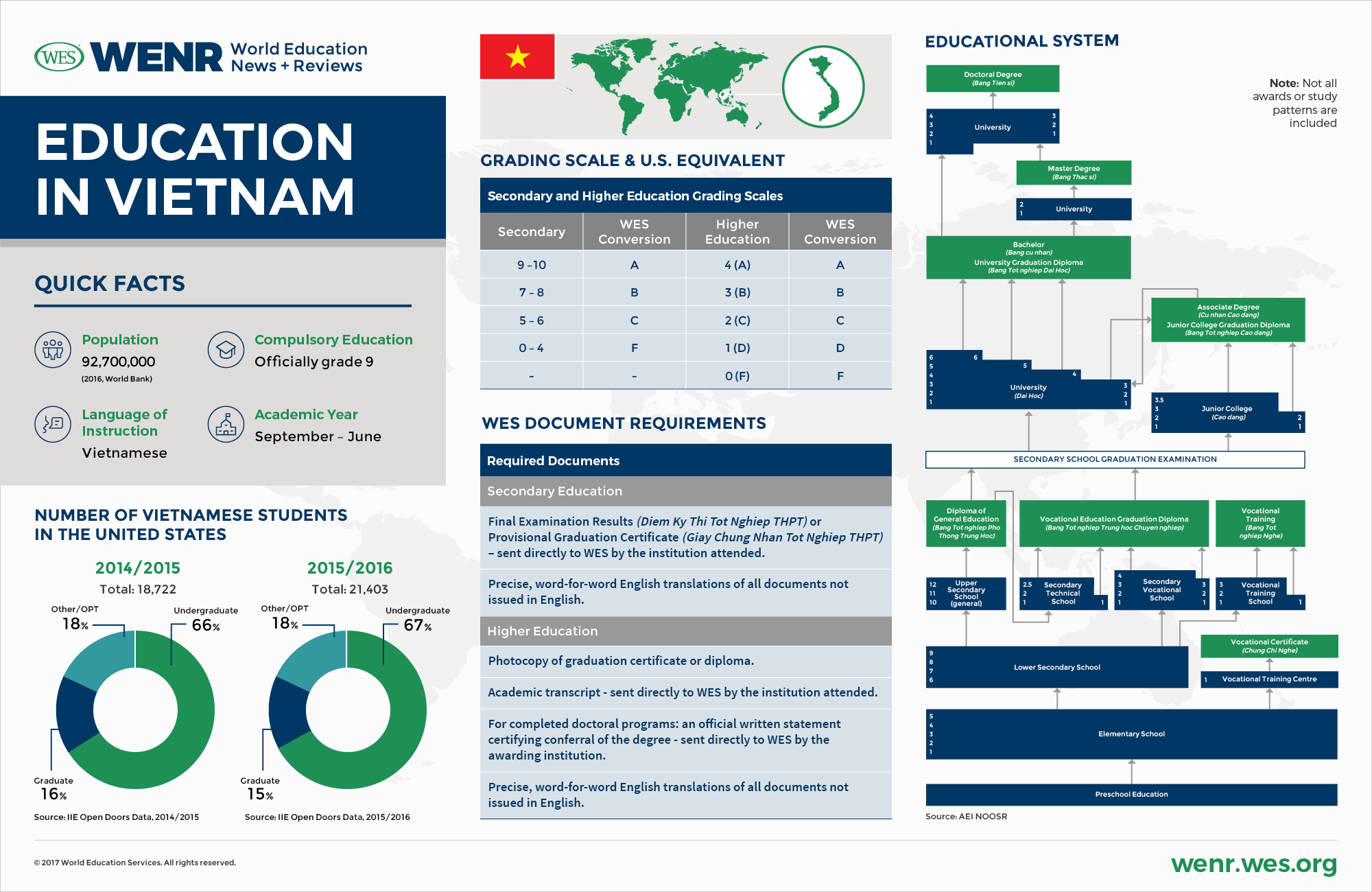

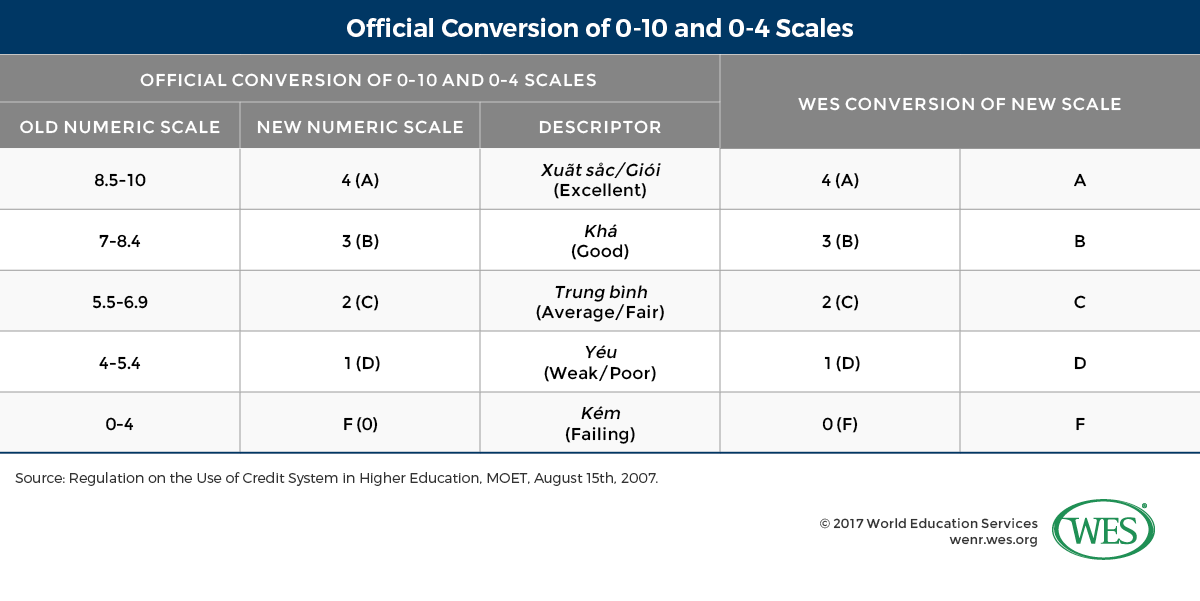

Together with the new credit system, the MOET mandated a new 4-point grading scale to be used alongside the old 0-10 grading scale. While courses can still be graded according to the old 0-10 scale, scores now need also to be converted into the new scale, and the final cumulative average of degree programs must be expressed in the 0-4 scale, respectively the corresponding letter grade. The official conversion between the two scales is listed below.

Vietnamese HEIs have since adopted different ways of indicating grades on their transcripts. While some schools have fully switched to the 1-4 scale, many list course grades according to both the 0-10 and the 1-4 scales on their documents. The final cumulative grade of the degree program is usually indicated in the new letter grade (A, B, C) or the corresponding descriptor (excellent, good, average). Some universities have also slightly adapted the 1-4 scale by using pluses and minuses (A+, A, A- etc.), similar to U.S. grading scales.

Development of a National Qualifications Framework

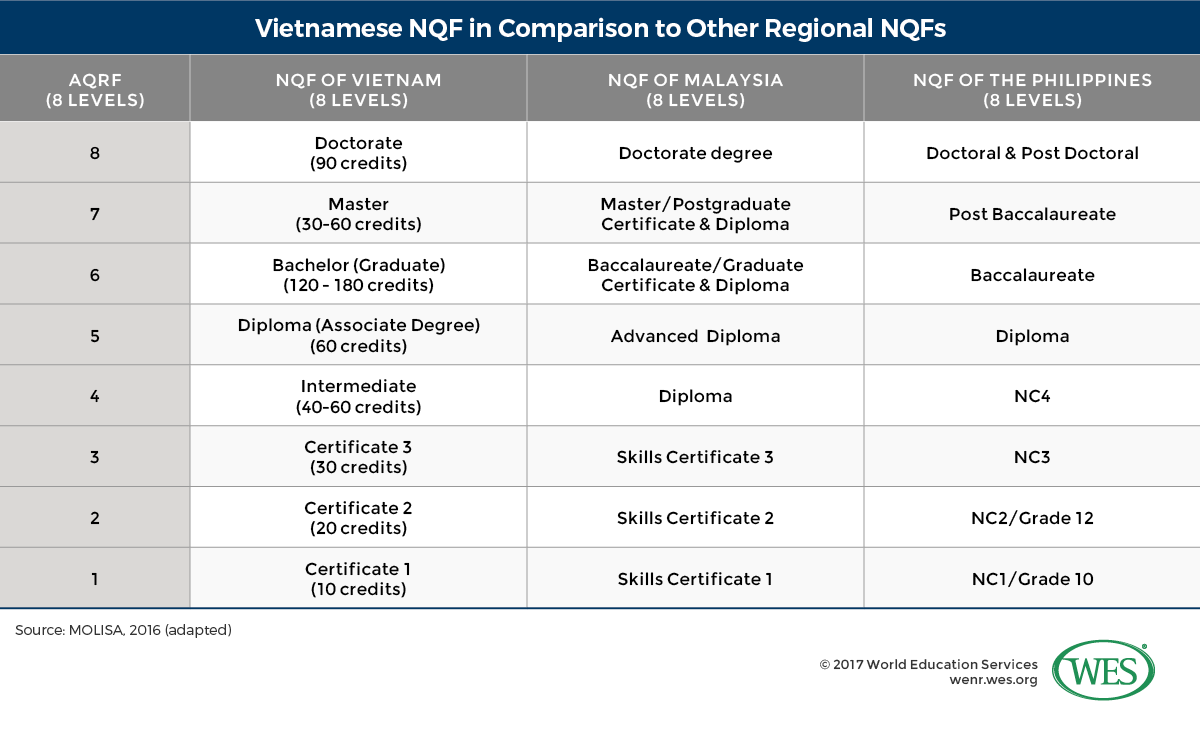

In November of 2016, Vietnam’s Prime Minister approved the implementation of a National Qualification Framework (NQF) developed by the MOET and MOLISA. The 8-level framework is aligned with the ASEAN Qualifications Reference Framework (AQRF) and intended to ease the international transferability of credentials. The framework also seeks to strengthen the quality of academic programs by defining learning outcomes and benchmark criteria for qualifications awarded at the different levels. As a first step towards implementation, these learning outcomes and benchmark criteria will now need to be defined. The British Council is presently assisting with the implementation of the framework. Another objective the government put forward alongside the NQF is the future shortening of university curricula. If implemented, these reforms could decrease the length of a standard bachelor’s degree in Vietnam from four to three years.

The Higher Education Degree System

At its core, the current degree system in Vietnam resembles the system of the United States. It includes an intermediate college degree, a four-year standard bachelor’s degree and a two-year master’s degree followed by a terminal research doctorate. All degree certificates from recognized Vietnamese universities must be officially approved and signed by the MOET.

Associate Degree (Cử Nhân Cao Đẳng) or Junior College Graduation Diploma (Bằng Tốt Nghiệp Cao Đẳng)

Programs are between 2 and 3.5 years in length and are known as “short-term training” in Vietnam. They are offered at junior colleges and some universities and require a minimum of 90 credits for three-year Curricula are typically applied and employment-geared in nature and include a practical training component. Graduates can be exempted from two years of study when transferring into bachelor’s programs at universities.

Bachelor’s degree (Bằng Cử Nhân)

Bachelor programs are studied at universities and are typically four years in length in standard academic disciplines. Graduates receive a University Graduation Certificate (Bằng Tốt Nghiệp Đại Học) that indicates the specific degree awarded. Credit requirements vary slightly from institution to institution but range from 120 to 140 credits. The final cumulative GPA must be 2.0 or higher for graduation. Curricula include a general education component in addition to specialized subjects. Programs may also include a thesis or internship and a graduation examination. Bachelor of Engineering (Bằng Kỹ Sư) programs are five years in length and require a minimum of 150 credits. Some bachelor programs can be studied in part-time mode.

Master’s degree (Bằng Thạc sĩ)

Admission into master’s program requires a bachelor’s degree and the passing of an entrance examination. Most programs are two years in length, but some programs in disciplines like engineering, for instance, may have a duration of 3 years. Part-time programs also last three Standard programs usually require between 40 and 45 credits for graduation and require the completion of a thesis.

Doctor of Philosophy (tiến sĩ)

Admission to doctoral research programs typically requires a master’s degree and the passing of an entrance examination. Programs have a minimum duration of two years with most being three years in length, even though candidates may take longer to graduate. Bachelor’s degree students with exceptionally high grades may also be admitted into doctoral programs, in which case the program lasts at least four years and incorporates a master’s degree. Completion of doctoral programs involves a set amount of coursework and preparation of a dissertation.

Professional Education and Training

First-degree programs in professions like medicine, dentistry, architecture, or pharmacy are long single-tier university programs of five or six-year duration entered after high school. Titles awarded include the bác sĩ (Medical Doctor), nha sĩ (Doctor of Dental Medicine) and dược sĩ (Pharmacist).

Medical education programs in Vietnam are six years in length and include a basic science component of two years followed by clinical theory and clinical practice in higher semesters. Admission at top universities is highly selective, but some second-tier universities admit students based on lower examinations scores. Shorter four-year programs have recently been introduced for assistant doctors with prior work experience. These programs are intended to train community physicians.

Graduation from medical programs requires passing a final examination conducted by the university. Licensure as a general practitioner requires 18 months of practice at a hospital or comparable institution after graduation. There are no separate licensing exams. Training in medical specialties lasts up to 4 years, depending on the specialty. The most common avenue for graduate medical education in Vietnam is a two-stage clinical training program offered by medical universities that leads to the award of a Specialist Certificate (Bằng Chuyên Khoa). Both stages (Specialist level 1 and Specialist level 2) last two years each.

Teacher Education

The practice requirements for teachers in Vietnam depend on the level of education. Pre-school and elementary school teachers must have a professional secondary school diploma in teaching (Bằng Tốt nghiệp Trung học Sư phạm), usually awarded by secondary teacher training schools. Lower-secondary school teachers commonly hold a teaching diploma from a pedagogical junior college (Cao đẳng Sư phạm), whereas upper-secondary teachers must have a bachelor’s degree in education from a pedagogical university (trường đại học Sư phạm). Holders of bachelor’s degrees in other disciplines can obtain a teaching qualification by earning a supplementary one-semester teacher training certificate (Chứng Chỉ Sư Phạm). In 2014 the MOET issued a directive that suspended this practice, but the ban seems to have been lifted, as universities are presently again offering these programs. Like other parts of Vietnam’s education system, teacher education is changing. The MOET seeks to strengthen teacher training while simultaneously trying to respond to teacher’s shortages. In 2012, authorities estimated that the country lacked 27,500 pre-school teachers alone.

WES Document Requirements

Secondary Education

-

- Final Examination Results (Điểm Kỳ Thi Tốt Nghiệp THPT) or Provisional Graduation Certificate (Giấy Chứng Nhận Tốt Nghiệp THPT) – sent directly to WES by the institution attended.

- Precise, word-for-word English translations of all documents not issued in English.

Higher Education

-

- Photocopy of graduation certificate or diploma.

- Academic transcript – sent directly to WES by the institution attended.

- For completed doctoral programs: an official written statement certifying conferral of the degree – sent directly to WES by the awarding institution.

- Precise, word-for-word English translations of all documents not issued in English.

Sample Documents

Click here for a PDF file of the academic documents referred to below.

- Secondary Education Graduation Diploma (Bằng Tốt Nghiệp Phổ Thông Trung Học)

- Secondary School Graduation Examination

- Professional Secondary Education Graduation Diploma (Bằng Tốt nghiệp Trung học Chuyên nghiệp)

- Junior College Graduation Diploma (Bằng Tốt Nghiệp Cao Đẳng)

- Bachelor (Bằng Cử Nhân)

- Degree of Doctor of Medicine (Bằng Tốt Nghiệp Bác Sĩ Y Khoa)

- Master (Bằng Thạc sĩ)

- Doctor of Philosophy (Bằng Tiến sĩ)

1. When comparing international student numbers, it is important to note that numbers provided by different agencies and governments vary due to differences in data capture methodology, definitions of ‘international student,’ and/or types of mobility captured (credit, degree, etc.) The data of the UNESCO Institute Statistics provides the most reliable point of reference for comparison since it is compiled according to one standard method. It should be pointed out, however, that it only includes students enrolled in tertiary degree programs. It does not include students on shorter study abroad exchanges, or those enrolled at the secondary level or in short-term language training programs, for instance.

2. Examples provided by Andrew Lawrence include unlicensed operators offering “… high-end degrees such as ‘American MBAs’. Despite charging as much as USD $3,500, they attract many students, enticed by the prospects of obtaining a foreign degree without having to know English… . An investigation by Thanh Nien News … , found two U.S.-based institutions, Southwest American University and Adam International University, were unaccredited in the U.S., yet offered 10-month MBA programmes for USD $4,000 to Vietnamese students. English language skills were not required and attendance was low (Thanh Nien News 2010). Quoted Lawrence, Andrew: Training the Dragon: Transnational Higher Education in Vietnam, MA thesis, Simon Fraser University, 2011, p.62, http://bit.ly/2xbi1jz. See also: http://bit.ly/2fFNVhT.

3. While most of these programs are offered at vocational schools, they may, on occasion, also be offered by junior colleges in the higher education sector.

4. Calculation based on population statistics and HE student statistics provided by the General Statistics Office of Vietnam. Unlike other countries which measure enrollment ratios as the proportion of students among the relevant age group, Vietnam measures participation rates by the number of students enrolled per 10,000 people of the total population. Studies using a different method found that Vietnam had a gross enrollment ratio (relevant age group) of 16 percent in 2007 – far lower than Thailand (43 percent), Malaysia (32 percent) and China (20 percent).

5. Stephanie Chow and Dao Thi Nga: Bribes for enrolment in desired schools in Vietnam, in: Transparency International, Global Corruption Report: Education, Oxford and New York, 2013, pp. 60 -67.