Jessica Magaziner, Knowledge Analyst and Carlos Monroy, Quality Assurance Manager for Latin America

Overview

One of the defining features of Mexico’s education system over recent decades has been that of expansive enrollment growth. From 1950 to 2000, total student enrollments in the formal education system — primary school through graduate studies — increased more than eightfold from 3.25 million students in 1950 to 28.22 million students in 2000. According to the most recent government data, that number had risen to 36.3 million [2] students across all education levels – or just shy of 30 percent of the total population – by the academic year 2015-2016. According to UNESCO, gross enrollment ratio [3] at the secondary school level has increased from just 54 percent in 1991 to 90 percent in 2014.1 [4]

At the tertiary level, the gross enrollment ratio of university-age students has risen significantly from 15 percent in 1991 to approximately 31.2 percent in 2016 [2]. Nonetheless, it lags the regional average (46 percent in 2010) by a large margin. By comparison, Argentina enrolled the equivalent of almost 80 percent of its college age population in 2013 and Brazil 46 percent, according to data from the UNESCO Institute of Statistics.

This large-scale growth in enrollments has placed tremendous pressure on the Mexican education system. Educational authorities and planners in Mexico are faced with two quite different and partially conflicting tasks: On the one hand, they must determine how to manage and increase educational access to accommodate mass demand; on the other hand, they must ensure educational quality. Beginning in the 1980’s and continuing through today, Mexico has sought to implement a series of measures aimed at both. These include:

- standardized national admissions and exit examinations at different levels of education

- teacher evaluation and professional development mechanisms

- institutional evaluation and accreditation reforms

- rankings for university degree programs

- increased requirements for mandatory schooling

- infrastructure improvement

- curricular reforms

- efforts to increase access among impoverished and rural populations

- and more

Public institutions remain the largest provider of higher education in Mexico, enrolling about 70.69 percent of the 3.6 million students in the tertiary system [2] as of 2015-2016. In the Latin American region, Argentina is the only country to have a higher rate of public institution enrollment (74 percent [6]). Like other Latin American countries, however, Mexico has seen a huge increase in the demand for tertiary education, and a concomitant rise in the number of private universities, especially in the last two decades, seeking to fulfill that demand. Many of these private institutions are low quality, with just a fraction having recognized accreditation. (For more on accreditation in Mexico, see “Recognition, Validation, and Accreditation,” below.) The private sector has a heavy concentration of programs in business-focused disciplines such as accounting and business. One result has been a glut of graduates with low-quality degrees and limited options for employment.

2013: A Watershed Year of Reform and Upheaval

In 2013, the SEP made 12 years of education compulsory [7] throughout Mexico. (Due to lack of capacity and infrastructure, the proposed date for full compliance is 2020, however due to resource constraints, full compliance is not expected.)2 [8]

That same year, Mexico’s federal government also initiated a series of education reform measures, passed as part of a far larger constitutional overhaul aimed at addressing education reform. The 2013 constitutional reforms sought to:

- Increase enrollment in secondary and tertiary education

- Provide greater fiscal and curricular autonomy to schools

- Improve teacher quality and accountability at the primary and secondary levels.

Additional legislation passed in 2013 established the National Institute for Assessment of Education (Instituto Nacional para la Evaluación de la Educación or INEE). The subject of heated protests, the institute seeks to reduce corruption in teacher-hiring practices, and enforce accountability by tying teachers’ pay, promotion, and tenure to performance on standardized exams. Educators, most of them members of Mexico’s strong teachers’ unions, have pushed back on the test-based reform initiatives. Demonstrations have led to repeated school closures (children in some states are estimated to have lost up to 85 school days), and sometimes deadly clashes between police and educators.

International Student Mobility

Per the UNESCO Institute for Statistics [9] (UIS), 27,118 Mexican students attended institutions abroad in 2013 (the most recent year for which UIS data is available). The United States was (and is) the most popular international destination for Mexican students, with over 50 percent of all internationally mobile students attending a U.S. institution of education. Historical and linguistic ties make Spain the second most popular destination, although enrollments there accounted for just nine percent of the overseas Mexican student body in 2013. The following most popular destination choices were France (2,181 students), Germany (1,830 students) the United Kingdom (1,645 students) and Canada (1,645 students). Mexico rounds out the top ten list of leading places of origin for students studying in the United States.

Efforts to Increase Mobility to and From Mexico

While the number of Mexican students studying in Canada is currently only five percent of the total students going abroad, there is potential for future enrollment numbers to increase. In 2016, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto forged a new partnership [10] to “increase the flow of students, ideas, and opportunities” between the countries’ educational institutions. The two men announced the removal, effective December 1, 2016, of a visa requirement (instituted in 2009) for Mexican students seeking to study in Canada.

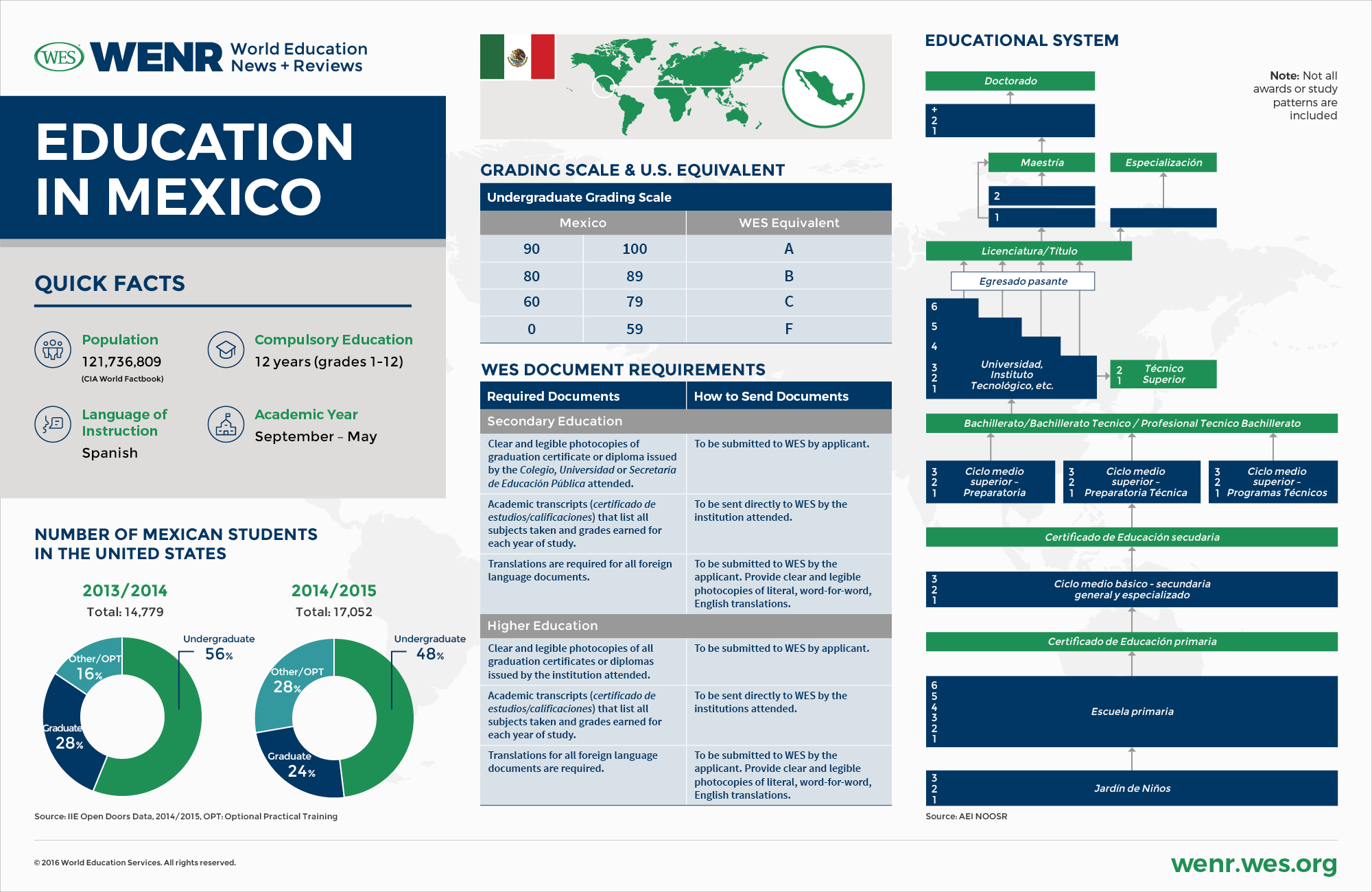

Of the Mexican students studying internationally, IIE Open Doors Data [11] for the 2014-2015 academic year show that 17,052 chose the U.S. as a study destination. This was a 15.4 percent increase from the 2013-2014 period. This is the highest growth rate seen in the last decade. Just over 48 percent of Mexican students in the United States enrolled at the undergraduate level. About a quarter of Mexican students (23.4 percent) were studying at the graduate level. Some 20.8 percent were enrolled in other programs of study, and 7.6 percent were engaged in optional practical training.

Mexico contributes a significant amount to the U.S. economy through its students. In 2014, Mexican students were responsible for bringing 473 million dollars to the U.S. higher education sector. A large reason for this is the geographic proximity of Mexico and the United States. The high and continually increasing population found near the U.S.-Mexican border is able to access U.S. higher education at nearby institutions. In addition to the geographic proximity, enrolling at a U.S. border institution can also be an affordable choice. In some cases, students are able to live in Mexico, but pay in-state tuition. This allows for significant financial savings on tuition, as well as room and board costs.

NAFTA has played a role in increasing the flow of Mexican students to the United States. After the trade agreement’s ratification in 1993, there was a slow, but generally steady increase of Mexican students coming to the U.S. The 2009-2010 academic year saw a significant dip of over nine percent in Mexican students, but has grown steadily since.

Some observers argue [12] that Mexico has the potential to be one of the leading suppliers of international students to the United States, behind China and India, thanks in part to national efforts on both sides of the border to increase transnational student flows. The 100,000 Strong in the Americas [13] program was commissioned by U.S. President Barack Obama with the “goal of more than doubling the number of U.S. exchange students in the Americas by 2020.” This was followed by Proyecta 100,000, an initiative by Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto to send 100,000 Mexican students (many of them-non-traditional or non-university) to the U.S., and to enroll 50,000 U.S. students at Mexican institutions. In its first year, the program offered thousands of scholarships for students and teachers to study English as a second language and to support participation in short-term study programs.

However, the program lost steam in years two and three; lack of funding led to a freeze on funding for traditional students. A handful of workers continue to be sent across the border under the program, an initiative which is low cost, thanks to participation by U.S.-based companies seeking to ensure that certain employees are proficient in English.

International Student Interest in Mexico

The number of international students who view Mexico as an education destination is relatively small. According to UIS data published in early 2016, [9] only 7,166 foreign students opted to study in Mexico. Top senders included the United States, Spain, Brazil, Cuba, and France.

U.S. numbers fluctuated in tandem with reports of violence and corruption along the border, and with the 2008 economic collapse. The number of U.S. students studying in Mexico hit an all-time high in 2005-2006, with a total of 10,022 students. This was followed by decreases until the 2012/2013 academic year. Traffic has recovered slightly in recent years. There were 4,445 American students studying in Mexico in the 2013-2014 academic year — a 19.2 percent increase from the previous year.

Policy, Administration, and Enrollment

The education system, including primary, lower secondary, public technological institutions, and teacher education programs are overseen either by the federal government, specifically through the offices of the Secretaría de Educación Pública [14] (SEP), or by Mexico’s 33 states, through various state departments of education.

The higher education system includes multiple types of public and private universities and other institutions, which must be accredited, but which are overseen by different administrative bodies. Higher education does not, in most cases, come under the direct control of the SEP. (Different types of higher education institutions are discussed in greater detail below.) In general, the SEP sets educational standards, and the scope and sequence of courses for the programs it oversees. Curricular requirements typically fall to state education departments. (A small percentage of primary and lower secondary schools follow a national curriculum established by the SEP.)

Public and Private Enrollments

In 2013-2014, about nine percent [15] of students aged 13 to 15 were educated at private lower-secondary institutions, while 91 percent attended public schools. About 81.4 percent [15] of upper secondary students are enrolled at public institutions; 18.6 percent study at private institutions. Most higher education enrollments are at public institutions (70.7 percent in 2015/16). The remaining 29.3 percent [15] of tertiary enrollments are in Mexico’s private institutions. All programs at private institutions must have official recognition status. (See “Recognition, Validation and Accreditation” below).

Structure of the Education System

The education system in Mexico can be divided into three main categories as follows:

- Educación Basica

- Preescolar (preschool): Ages 3–6

- Educación primaria (primary education): Grades 1–6

- Educación secundaria (lower secondary education): Grades 7–9

- Educación Média Superior (Upper Secondary): Typically Grades 10–12

- Profesional Técnico

- Bachillerato

- Educación Superior

- Técnico Superior

- Normal Licenciatura

- Licenciatura Universitaria y Tecnológica

- Posgrado

Basic Education

Since 2004, one year of free, preschool (preescolar) education has been mandatory nationwide.

The SEP has gradually increased the period of mandatory education for students nationwide. In 1992, compulsory education was extended from completion of primary school (grade six) to completion of lower secondary school (grade nine). Reforms in 2012 made upper-secondary education compulsory [7] for all students. The new education system requires twelve years of elementary and secondary study. (In some states, upper secondary is complete at grade 12; in others, it is complete at grade 11.) However financial and administrative obstacles had led to uneven implementation as of late 2016. Although the government set a compliance deadline of 2020, ongoing lack of funding is expected to make adherence impossible in many districts, especially those that are largely rural and impoverished.

Primary/Elementary Education

Primary education is six years in length, and runs from grade one through grade six. Instruction is offered in primary schools that are alternatively known as colegios (typically private), institutos, or escuelas (typically public).

The SEP sets governance and standards at the primary level; state departments of education establish the curriculum for most schools within their jurisdictions, dependent on the characteristics of the local populations (language, etc.) The National Institute for Assessment of Education (Instituto Nacional para la Evaluación de la Educación [16] [INEE]) monitors standards in schools.

Upon completion of primary school, students are awarded the Certificate of Primary Education (Certificado de Educación Primaria).

Lower Secondary Education (Educació Secundaria)

Lower secondary education (escuela secundaria) is three years in length, and runs from grade seven through grade nine. (NOTE: The term “secundaria” always refers to lower-secondary study and never higher-secondary study.)

Students follow either an academic track (educación secundaria general) or a technical track (educación secundaria técnica). Instruction is offered at escuelas, institutos or colegios. Graduating students are awarded the Certificate of Secondary Education (Certificado de Educación Secundaria).

General admission requirements to lower-secondary school include completion of primary education and in some cases entrance examinations. The curriculum at this level has some variations by state, but students generally take classes in biology, chemistry, physics, a foreign language, arts, and technology. These classes may be accompanied by subjects and content relevant to the local area as decided by the relevant state department of education [17].

Upon completion of the three-year escuela secundaria, students receive a comprehensive transcript that allows them to apply to upper-secondary education.

Upper Secondary Education (Educación Média Superior)

Upper secondary education follows lower secondary, and is mandatory. It typically runs for three years, from grade 10 to grade 12; in a small number of regions, upper secondary school lasts only two years.

There are a range of different schooling options at the upper secondary level. These include: SEP-controlled schools, state-controlled schools, and schools administered by autonomous universities . Private schools that are recognized by any of the three main administrators are also part of the upper secondary system.

Each type of school provides certificates and/or transcripts endorsed by the affiliating university or the relevant government oversight body.

Admission requirements for upper-secondary school depends vary based on administrative oversight. Standardized examinations developed by CENEVAL/Centro Nacional de Evaluación [18] (National Center for Evaluation) are used as an admissions criteria for those upper-secondary schools that are administered by the federal government. Schools administered by state departments of education or autonomous universities have other admissions criteria.

Once admitted, students at the upper secondary level generally follow one of two tracks. The two tracks include, academic university-preparatory schools and professional technical education. These are detailed below.

Academic University-Preparatory Bachillerato General Programs

Academic University-Preparatory Bachillerato General programs lead to the award of a certificado de estudios (transcript) attesting to completion of the program. The transcript is issued or endorsed either by the autonomus higher education institution with which the higher secondary school is affiliated, or by the supervising governmental agency. Academic university-preparatory programs traditionally prepare students by discipline — streaming them immediately into specialized areas as pre-engineering, pre-medicine, or the humanities among others. More recently, however, the trend [19] has been towards a more general academic curriculum during the first two years, followed by specialization in the third year. A foreign language (typically English) is generally, but not always, compulsory.

NOTE: Upon graduation from academic preparatory schools, upper secondary students do not always receive a separate document (e.g., a diploma or degree certificate) indicating conferral of the title of bachiller ; instead students’ transcripts will indicate that they have finished the study of the “bachillerato” or the “preparatoria.” This is true of students who complete academic university-preparatory programs as well as of those who complete technical programs that incorporate university preparatory studies (discussed below), This situation is notable because it differs from that of most Latin American countries, where upper secondary students receive diplomas, rather than just transcripts.

Professional Technical Education (educación profesional técnica)

Professional technical education (educación profesional técnica) leads to the título de técnico profesional (title of professional technician). This sector of upper-secondary study was formerly classified as terminal vocational study, but in 1997 the SEP designated it as “preparatory.” Holders of the título de técnico profesional are now officially eligible for admission to all post-secondary degree programs. (See “Educación Superior” – below – for additional detail on licenciado programs.) Students in professional technical education programs take general education classes (mathematics, English, sciences, etc.) in addition to professional classes in their field of specialization. There is also a period of practical training and community service embedded in these programs.

Higher Education

Mexico’s system of higher education has seen dramatic growth over the last 45 years. In the period 1971 to 2000, total enrollment increased more than six-fold from 290,000 to 1,962,000, rising to 3.6 million [2] in the 2015-2016 year. As in other countries that have seen massification of the higher education sector, this expansion mirrors the country’s rapid economic development and answers the needs of a growing middle class. According to government data, there were more than 3,100 [20] institutions of higher education in Mexico in 2015.

About 70 percent of tertiary students study at public universities; however private sector enrollments are up dramatically. As of 2016, the private sector now enrolls just over one million students [21], up from 400,000 in 2006. Quality in the private higher education sector is radically uneven, with a handful of “Ivy League” type schools obtaining prestige and respect, and a substantial cohort of newer upstart schools seeking to absorb demand without much regard for either academic standards or student outcomes.

Types of Higher Education Institutions

Higher Education institution types include the following:

- Subsistema de Universidades Públicas (Public University Subsystem): This system includes 61 federal and state universities. These institutions have autonomy over management, budgeting, and curricular content. They may also incorporate, and therefore bestow official validity on, programs offered at private institutions. The largest such university, the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico [UNAM] enrolled 234,501 tertiary-level students [22] in 2015-2016.

- Non-autonomous federal institutions under the purview of the SEP or other ministries must follow study requirements determined by the state. Titles and transcripts are issued, or endorsed by the controlling governmental body.

- Subsistema de Educación Tecnológica (Technological Education Subsystem): Research-based science and technology institutions include 39 polytechnic universities and 218 technological institutes offering university degrees in engineering and applied sciences. These institutions tend to be very specialized, offering programs in just a few fields of study.

- Subsistema de Universidades Tecnológicas (Technological University Subsystem): This system includes 61 institutions administered by state authorities and authorized by guidelines established by the SEP. Institutions in the technological university subsystem offer two-year técnico degree programs incorporating on-the-job training in applied disciplines.

- Subsistema de Educación Normal (Teacher Training Subsystem): Institutions in the system offer licenciado degree programs for all types and levels of teacher training.

- Subsistema de Otras Instituciones Públicas (Other Public Institutions Subsystem): This system includes 116 specialized institutions of higher education including the Instituto de Antropología e Historia, schools belonging to the umbrella institution of the Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes, and institutions of the armed forces.

- Subsistema de Instituciones Particulares (Private Institution Subsystem): This system includes approximately 2,100 [20] private higher education institutions whose programs of study are supervised by either federal or state ministries, or by public autonomous universities. Private institutions of higher education offer all types of degrees in all disciplines. Programs with official validity at private institutions of higher education are incorporated under a public autonomous university or are recognized by the SEP or the relevant state department of education. (Degrees from incorporated programs are issued by the incorporating autonomous university; however, transcripts may be issued by the private institution.)

Admission to Higher Education

Selection procedures at different institutions vary greatly, depending on demand. Typically, entrance examinations and bachillerato grade point averages are used to filter students.Completion of an academic or technical upper-secondary program (bachillerato or profesional técnico) is ordinarily required for admission. Certain university departments also require that incoming students complete higher-secondary programs in a track relevant to their prospective major field of study. Mexico, until relatively recently, had no national standardized examination to indicate the academic performance of upper secondary graduates.

Since 1994, higher secondary exit examinations designed by CENEVAL have been used for admission to higher education institutions administered by the federal ministry of education. Institutions administered by state departments of education may use national exam for admissions. However, most universities that are not administered by the federal government, including private autonomous universities, have developed their own testing protocols. Some universities also use a Spanish version of secondary school examinations designed by the College Board [23] in the United States as an admissions examination.

Recognition, Validation, and Accreditation

In Mexico, the Validez Oficial de Estudios (Official Validity of Studies) serves as the basic indicator of governmental and professional approval of higher education programs. It represents the closest equivalent to regional accreditation in the United States.

Private higher education institutions must, in most cases, be officially recognized [24] by state educational authorities. Their programs of study must likewise be recognized by the federal or relevant state ministry of education. To obtain this recognition, private academic institutions must submit an application detailing study plans and teaching personnel to the relevant authorities. Programs that are granted approval receive the legal classification Reconocimiento de Validez Oficial de Estudios/RVOE (Recognition of Official Validity of Studies).

NOTE: Private institutions with recognized programs issue their own degree certificates and academic transcripts. By law these documents must note RVOE status; some certificates and transcripts may also bear the seal or signature of the government agency that oversees them. Private institutions may also be affiliated with public autonomous universities by “incorporación”; this is an alternate route to official recognition or accreditation. In this case, degree granting authority resides with the autonomous university with which the incorporated institution is affiliated.

COPAES

El Consejo para la Acreditación de la Educación Superior, A.C. — COPAES (Higher Education Accreditation Council) is a non-profit civic organization that since 2000 has been charged by the SEP to recognize official accrediting bodies in different fields of study. Those accrediting bodies then accredit undergraduate degree programs (licenciado, técnico superior/profesional asociado), designating them to be of “good quality” (buena calidad) if successful.

The accrediting bodies must renew their recognition status with COPAES every five years. Institutions must likewise submit accredited degree programs to a re-evaluation every five years. Accredited programs enjoy higher academic prestige both nationally and internationally, and are eligible for additional governmental financial support and grants. As of July 2016, COPAES had recognized a total of 3,832 programs.

NOTE: Accreditation of university degree programs through COPAES is voluntary.

CONACYT

The National Council for Science and Technology [25] (Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología–CONACYT) evaluates [24] graduate programs at public and private higher education institutions for designation as ‘graduate programs of excellence’ (programas de posgrado de excelencia). It evaluates especialista, maestría and doctorado programs. Those that meet the minimum standard are listed on the National Registry of Graduate Studies (Padrón Nacional de Posgrados de Calidad [26] or PNPC). Programs are classified as either High Level (Alto Nivel) or Competent on an International Level (Competencia Internacional).

NOTE: In the private sector, few institutions submit their programs for quality assurance audits. The Secretariat of Education is exploring various options to ensure institutional quality and to be competitive with global universities. Ideas [27] to improve standards in the private tertiary sector include university-business partnerships as well as following British accreditation models.

Higher Education Degree Programs and Qualifications

Undergraduate

Associate Degree (Técnico Superior Universitario / Profesional Asociado)

The Técnico Superior Universitario (University Higher Technician) or Profesional Asociado (Professional Associate) programs are generally two years in length and undertaken in specialized fields. The degrees are either a terminal award or offer advanced placement into liceciatura or titulo profesional programs.

These programs are mainly offered at universidades tecnológicas and consist of six 15-week semesters. Thirty percent of the curriculum focuses on theoretical instruction, and 70 percent practical instruction and projects. Until the founding of these institutions, most technological studies were offered either at the upper-secondary level or in four- or five-year university degree programs. This relatively new system remains still quite small in terms of enrollment, and comprised about 4.5 percent [28] of the total higher education study body as of 2014-2015.

Certificato/Diplomado Programs

Other short, applied programs include a certificado or diploma in a specialized field. Certificato/Diplomado programs (certificate-level programs) run from one to three semesters, while salida lateral programs last up to four years and sometimes account for the first one or two years of a licenciatura or titulo professional program.

Licenciado and Titulo Profesional Degrees

Both the licenciado and titulo profesional (used interchangeably) are first-degree programs lasting between three and six years. Programs usually include both coursework and the submission of a thesis or a degree project. They tend to be specialized programs focused on professional training. Examples of five-year programs are: architecture, dentistry, and veterinary science. Medicine is a six-year program. Graduates are typically licensed to practice at graduation.

Currently, the escuelas normales superiores are state-supervised teacher-training programs that run for four years. They offer licentiate degree programs for preschool, primary school, secondary school, special education, and physical education teachers.

The Carta de Pasante

Students who have completed all their coursework for a particular program, but have not completed a thesis or other graduation requirements, may receive a certificate called the carta de pasante (leaving certificate) and attain the status of an egresado/pasante. Students who obtain this status do not have a degree, and they do not have the professional privileges in their field of study accorded to licenciados (holders of the licenciate degree). The carta de pasante may qualify students for conditional admission into graduate school at some institutions.

Although students who earn the classification of egresado/pasante cannot be licensed in their respective profession or practice it as a fully recognized profession, they do often find employment in their field of study, often in an auxiliary capacity for the more regulated professions. For example, a student who has obtained the carta de pasante, but not the licenciatura degree, in a law program cannot practice as a licensed lawyer, but might be able to work as a paralegal. In other industries that are less regulated than law, for example, business administration or engineering, an egresado/pasante might well find a very desirable position without the benefit of the final licenciado degree.

NOTE: Many institutions of higher education issue students a “diploma” following completion of coursework in a program, but before completion of the graduation requirements, and thus before the licenciado degree has been officially awarded. Students may also receive a “diploma por pertenecer a la generación de XXXX” (“diploma for belonging to the class of XXXX”). If the diploma does not state that the student has completed all required coursework, and if the transcript does not clearly demonstrate degree completion, further scrutiny is required to verify that the student has actually completed all coursework in the certificate program and met the graduation requirements for the final degree.

Graduate Programs

Especialista (Specialist)

Usually one year in length (but up to four in medicine), cursos de especialización programs build on the licentiate degree, and are typically a more applied graduate curriculum than a full-fledged Maestría (master’s) program; some may constitute the first year of a Maestría. Completion of coursework is required; a thesis is generally not.

Grado de Maestro (Master’s degree)

Generally two years in length, the maestría program requires the completion of coursework and typically a thesis. A bachelor’s degree (Licenciado/Título Profesional) is required for admission.

Doctorado (Doctorate)

Doctoral programs require at least two years of study, including completion of coursework, original research, and a dissertation.

Credit System

Not all institutions of higher education employ a system of course credits to measure in a quantitative manner the amount of study completed in a program, and not all institutions employing credits use the same definition.

A unified/national credit definition or credit system does not exist and it is not mandatory in Mexico; three major credit systems (none of which is nationally enforced) co-exist. It can be challenging to understand which credit system an institution uses, if any.

Prior to 2000 the only credit system in place was the one introduced in 1972 (Acuerdos de Tepic). The 1972 credits are used by most autonomous universities and most public institutions that operate under the auspices of the national or state educational authorities. Under the Acuredos de Tepic of 1972, 15 hours of instruction = 2 credits and 15 hours of lab = 1 credit.

In 2000, the Acuerdos SEP 279 and 286 slightly revised the definition/allocation of credits, and in 2007 a new proposal (SATCA) was introduced. Private institutions that are recognized by the state educational authorities often do not use credits at all. The SATCA credits define one credit as equivalent to 15 to 16 classroom instruction hours. These credits are not defined in classroom instruction hours but in “hours of effective learning activities. The minimum number of required credits for a licenciatura program, as defined in 2000, is 300.

Assessment and Grading

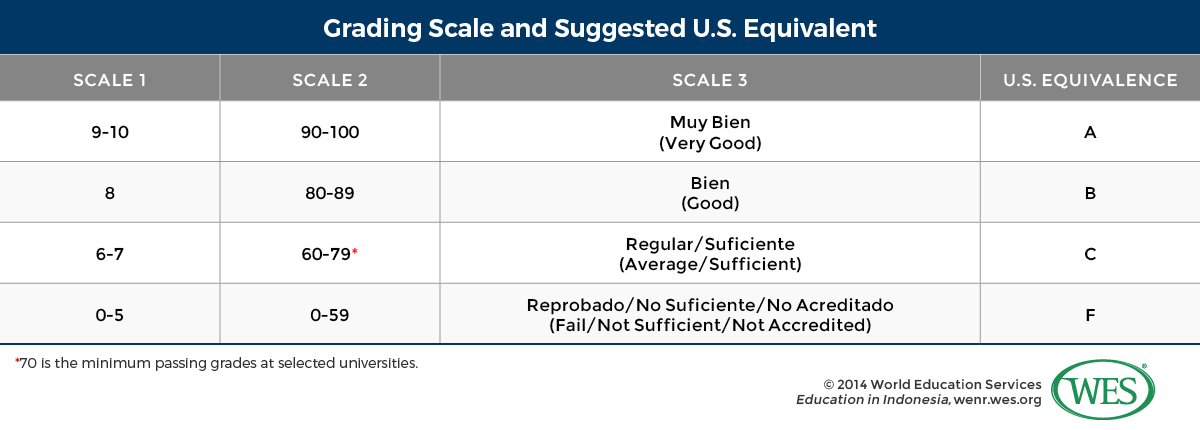

A range of grading scales are used in Mexico, the following table provides the WES suggested equivalency for the three most common grading scales.

*On many 10/100-point scales, 7/70 is the lowest passing score. A failing grade of “no acreditado” can in some instances mean “examination not sat.” The same scales are used for graduate studies, but often one bracket higher (“Good”) is needed for passing.

Required Documents Checklist

Secondary Education

- Clear and legible photocopies of graduation certificate or diploma issued by the Colegio, Universidad or Secretaría de Educación Pública attended are to be submitted by the applicant.

- Academic transcripts (certificado de estudios/calificaciones), that list all subjects taken and grades earned for each year of study, are to be submitted by the institution attended.

- Translations are required for all foreign language documents.

Higher Education

- Clear and legible photocopies of all graduation certificates or diplomas issued by the institution attended are to be submitted by the applicant.

- Academic transcripts (Certificado de estudios /calificaciones), that list all subjects taken and grades earned for each year of study, are to be submitted by the institution attended.

- Translations for all foreign language documents are required.

Sample Documents: Mexico

Sample Documents: Mexico

This file [30] of Sample Documents (pdf) shows the following set of annotated credentials from the Mexican education system:

- High school academic transcripts from a public university, Universidad de Guadalajara

- English translation of high school academic transcripts

- High school academic transcripts from a private secondary institution, including grading scale information

- English translation of high school academic transcripts

- Bachelor’s degree certificate (licenciado) from a public university, Universidad Nacional Autonoma de México

- English translation of degree certificate

- Academic transcripts for the bachelor’s degree from Universidad Nacional Autonoma de México

- English translation of academic transcripts

- Bachelor’s degree certificate (licenciado) from a private university, Universidad La Salle

- English translation of degree certificate

- Academic transcripts for the bachelor’s degree from Universidad La Salle

- English translation of academic transcripts

- Master’s degree certificate (maestro) from Universidad de Guanajuato

- English translation of degree certificate

- Academic transcripts for the master’s degree from Universidad de Guanajuato

- English translation of academic transcripts

2. [31] In most states, the 12-year requirement has been interpreted as including secondary education through grade 12. In a handful of states, the requirement is interpreted as extending only through grade 11.