Education in Mexico

Carlos Monroy, Advanced Evaluation Specialist, WES, and Stefan Trines, Research Editor, WENR

Introduction

Mexico’s new president, the former mayor of Mexico City, Andrés Manuel López Obrador—nicknamed “AMLO”—took office in December 2018. The election of a leftist populist in the nation of about 129 million people adds an interesting twist to Mexico’s already strained relations with the United States during the Trump presidency. If AMLO’s campaign promises become reality, they could bring about major changes for poor and marginalized social groups in Mexico, a country marred by wealth disparities where some 7 percent of the population still lives on less than USD$2 per day. AMLO has pledged to alleviate poverty and end corruption. His ambitious promises include massive railway construction projects, free internet throughout the country, a freeze in gasoline prices, and the doubling of pension payments for the elderly. Six months into the new administration, the record on these promises is mixed, and many observers doubt whether they can be paid for.

AMLO has vowed to accommodate the surging demand for education by building 100 new universities, eliminating university entrance examinations, and allowing “every person access to higher education.” According to UNESCO statistics, tertiary enrollments in Mexico have more than doubled, going from 1.9 million to 4.4 million between 2000 and 2017,1 placing tremendous stress on Mexico’s education system. Despite that growth and recent leaps in educational participation, the country’s tertiary enrollment rate still trails far behind those of other major Latin American countries. For example, the tertiary gross enrollment ratio (GER) stood at 38 percent in Mexico in 2017, while it ranged from 50 percent in Brazil to 59 percent in Colombia and 89 percent in Argentina, per UNESCO.

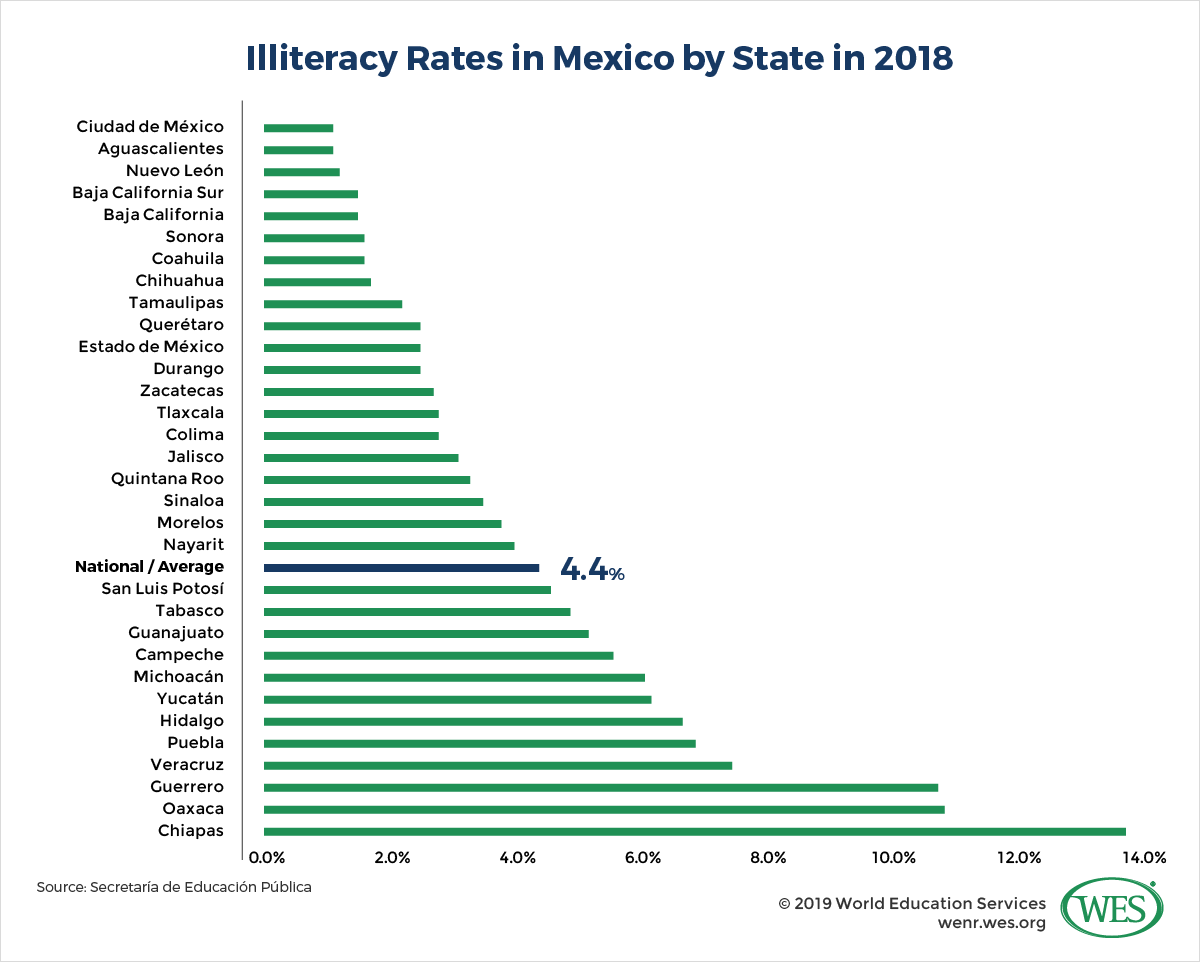

Two reasons for these relatively low participation rates are capacity shortages and disparities between the more industrialized central and northern parts of Mexico and the less developed southern states like Chiapas, Oaxaca, Yucatan, and Tabasco. Mexico is a geographically, ethnically, and linguistically diverse country that comprises 32 states. Its more than 60 languages are spoken mostly by indigenous ethnic groups in the south, a region historically neglected by the central government. It is within these underfunded rural regions that educational participation and attainment rates are extremely low. Literacy rates in the states of Chiapas and Oaxaca, home to the largest percentages of indigenous peoples in Mexico, are more than 10 times lower than in Mexico City or the northern state of Nuevo León.

In an attempt to raise education participation rates across the nation, the Mexican government in 2012 made upper-secondary education compulsory for all children by 2020. However, inadequate funding and administrative obstacles have thus far prevented universal implementation of this goal, particularly in marginalized rural regions. The new AMLO administration has also vowed to provide financial assistance to upper-secondary students to reduce high school dropout rates.

Despite the still comparatively low enrollment ratios, Mexico is expected to be one of the world’s top 20 countries in terms of the highest number of tertiary students by 2035. It will be a key challenge for the Mexican government to ensure quality of education amid this rapid massification. The problems Mexico faces in this regard are manifold. The country ranks at the bottom of the OECD PISA study2 and ranked only 46th among 50 countries in the 2018 Ranking of National Higher Education Systems by the Universitas 21 network of research universities.

Attempts by the administration of President Enrique Peña Nieto (in office from 2012 to 2018) to improve teaching standards are currently in limbo. Nieto had sought to raise standards for the hiring, evaluation, and promotion of teachers, but the reforms were met with fierce resistance from Mexico’s powerful National Teacher’s Union (SNTE)—the largest teacher’s union in the Americas with about 1.5 million members that has been repeatedly charged with corruption. In the presidential elections, the SNTE supported AMLO, who vowed to end the controversial reforms. Noting that new evaluation mechanisms for teachers had resulted in a 23 percent enrollment decrease at public teacher training colleges and increasing numbers of teachers requesting retirement, the new administration has promised to reinstate teachers that had been laid off because they had refused to submit to performance exams. Other changes include the dismantling of the National Institute to Evaluate Education (INEE), an autonomous body under the Ministry of Education tasked with reducing corruption in teacher-hiring practices, and holding teachers to account by tying their pay, promotions, and tenure to performance on standardized exams.

Improving Mexico’s education system is critical for addressing pressing problems like high unemployment rates among Mexican youths, who are unemployed at twice the rate of the overall working age population. There were reportedly 827,324 young people unable to find unemployment in Mexico in 2018 —58 percent of whom held an upper-secondary school diploma or university degree. However, structural problems and severe funding shortages continue to impede progress. As U.S. News and World Report reported in 2018, “… education spending dropped by more than 4 percent compared to the previous year, with the textbook budget cut by a third and funding for … educational reforms … slashed by 72 percent. (…) “Meanwhile, the 2017 budget for teacher training was cut by nearly 40 percent.”

International Student Mobility

Mexico is an important sending country of international students in the Americas, notably to the neighboring United States. Between 2000 and 2017, the number of international degree-seeking Mexican students increased by 114 percent, from 15,816 to 33,854 students, according to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS). Among the drivers behind this growth is the vastly increased number of tertiary students in Mexico, as well as the country’s rising number of middle-income households—factors that enlarge the pool of potential international students able to afford an education abroad. Mexico’s tertiary student population more than doubled since the beginning of the last decade, from 2 million in 2001 to 4.4 million in 2017, as per UIS. The number of middle-income households earning an annual salary of between USD$15,000 and USD$45,000 simultaneously quadrupled and accounted for up to 47 percent of all households in 2015.

Another factor that helps drive growing numbers of students overseas is the surging demand for English language education in Mexico due to the increasing internationalization of Mexico’s economy, its need for skilled human capital, and the growth of Mexico’s tourism industry. It has been estimated that the number of outbound English Language Teaching (ELT) students increased by 35 percent between 2011 and 2013 alone, making Mexico the 18th-largest market for ELT in the world. Many Mexicans view English language acquisition as an investment that is positively correlated with occupational status and household income. In the long term, Mexico has tremendous potential for further increases in outbound student flows underpinned by continued population growth. While birth rates in Mexico have fallen significantly and Mexican society is aging, about 46 percent of the country’s population is still under the age of 25. The total population is expected to grow to 164 million by 2050 (UN medium variant projection). It should be noted, however, that there’s been a shift away from the U.S. and a greater diversification in destination countries in recent years.

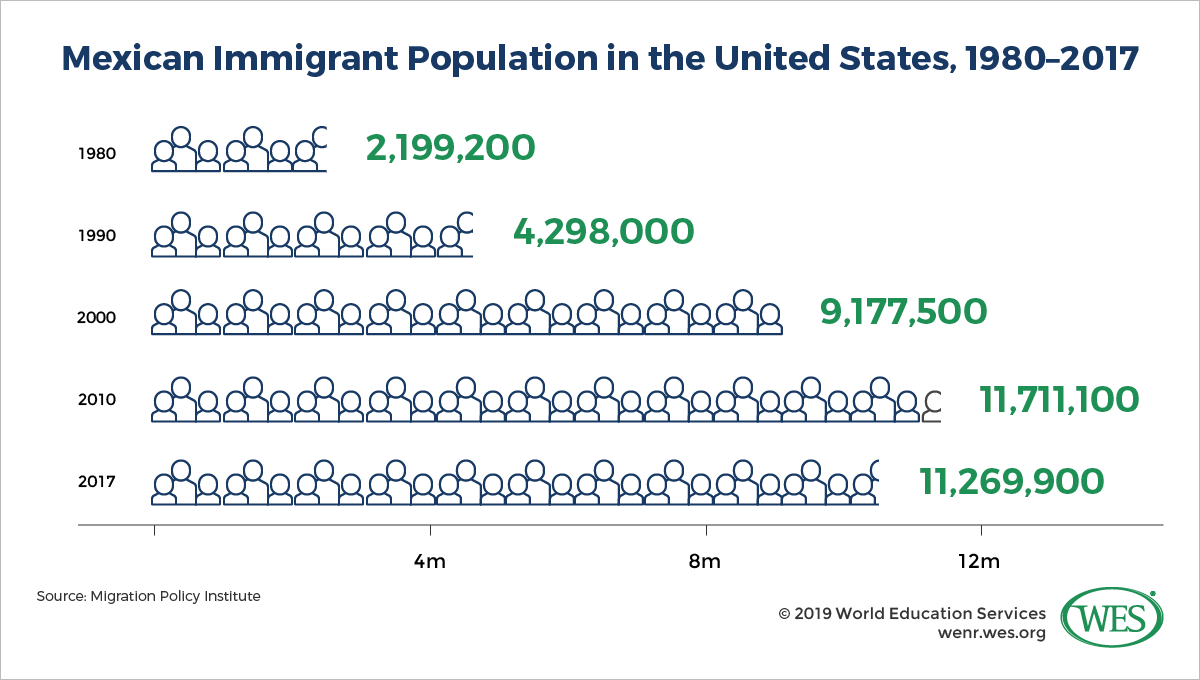

Downturn in Student Flows to the U.S.

According to UNESCO, the U.S. is by far the most popular study destination of Mexican students. The organization’s data show that about half of all international Mexican degree-seeking students (17,032 in 2017) are enrolled in the U.S., trailed distantly by Spain with 2,447 students, France (2,433 students), the United Kingdom (2,008 students), and Canada (1,587 students). While Mexican immigration to the U.S. has slowed in recent years, Mexicans are still the largest immigrant group in the U.S. with 11.3 million people—a vast transnational network that helps drive student inflows. Geographic proximity also makes the U.S. an obvious choice for many Mexican students. More than 40 percent enroll in states close to the border where they can save on housing and tuition costs by living in Mexico while paying in-state tuition at a number of institutions, such as the University of Texas at El Paso, the largest host university of Mexican students, New Mexico State University, and the University of North Texas.

Economic integration within the North American Free Trade Agreement has also helped spur student inflows and created an environment that stimulated university partnerships, dual degree programs, and research collaborations, often involving institutions close to the border. Finally, academic exchange between the two countries has been fueled by the establishment of large-scale scholarship programs on both sides of the border in recent years. Mexico, for instance, in early 2014 initiated Proyecta 100,000, a project aimed at boosting Mexican enrollments in the U.S. to 100,000 by 2018 with scholarships and university partnerships, while increasing the number of U.S. students in Mexico to 50,000. According to Open Doors student data of the Institute of International Education (IIE), Mexican enrollments in the U.S. increased by 15.4 percent between 2012/13 and 2014/15 alone. These gains followed an increase in Mexican student enrollments by 50 percent over the previous 14 years, from 9,641 students in 1998/99 to 14,199 students in 2012/13.

However, such increases came to a halt in 2015, and Mexican student enrollments have recently tanked. While there may be additional factors at play, it is likely that the anti-Mexican demagoguery of Donald Trump has had a chilling effect on Mexican students and their parents. A survey of 40,000 international students conducted in March 2016 found that as many as 8 in 10 Mexican students were less likely to study in the U.S. if Trump won the election—far more than the global 6 out of 10. These sentiments are also reflected in other opinion polls. The PEW Research Center reported in 2017 that favorable views of the U.S. in Mexico had dipped by 36 percentage points since Trump took office—the steepest drop in all countries surveyed. Only 30 percent of Mexicans held positive views of the U.S., while confidence in Trump was merely 5 percent—the lowest rating of any U.S. president since Pew began polling in Mexico.

The number of Mexican enrollments declined by 8.1 percent between 2016/17 and 2017/18 (IIE), even though Mexico remains the ninth-largest sending country of international students to the U.S.—and there are currently few signs that this trend will reverse in the near future. Current visa data by the Department of Homeland Security reflect a further decrease of 3.8 percent in active student visas held by Mexican nationals between March 2018 and March 2019.

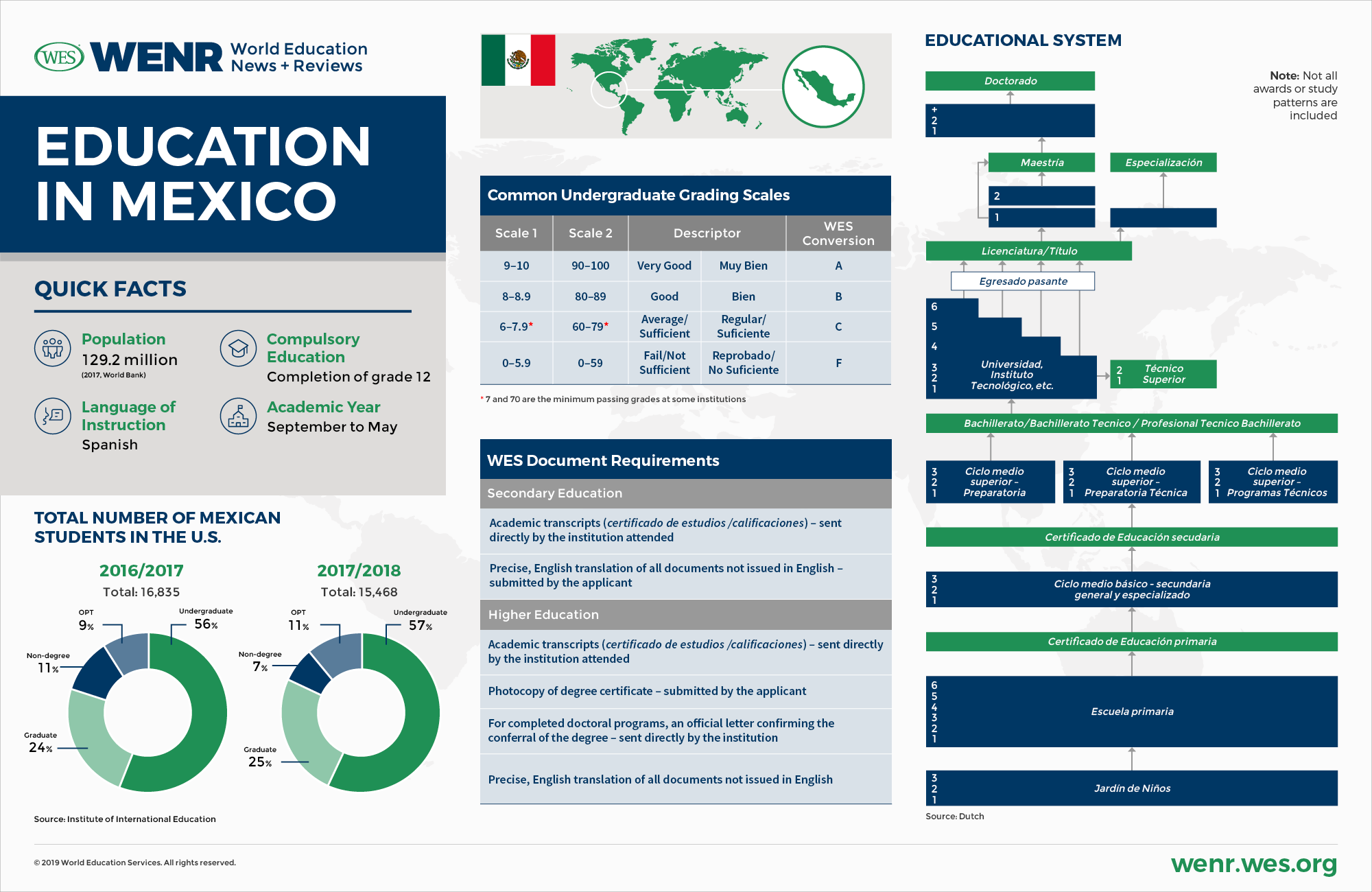

According to IIE, there are presently 15,468 Mexican students in the U.S., 57 percent of whom study at the undergraduate level. Another 25 percent study at the graduate level and 7 percent in non-degree programs; the latter category has seen a drastic decline of 39 percent between 2016/17 and 2017/18. Eleven percent pursue Optional Practical Training; business and engineering fields are the most popular majors among Mexican students.

Shifts to Other Destinations

Whereas Mexican enrollments are declining in the U.S., other countries are experiencing gains. The number of Mexican degree students in Germany, for instance, grew by 23 percent between 2013 and 2016, per UIS data. That said, given the surging demand for ELT in Mexico, English-language-speaking destinations like the U.K. or Australia, where Mexican enrollments have lately also grown robustly, may benefit most from shifting Mexican student flows. This shift is reflected, for instance, by a growing interest in Canada. While the number of Mexican degree students in Canada is still small with 1,587 students in 2016 (UIS), the Canadian government reports that the overall number of students, including non-degree students, now stands at 7,835—an increase of 132 percent over the number in 2008.

It is likely that ELT enrollments are a strong driver of this growth. Canada’s government has made increased efforts to attract Mexican ELT students. It expanded air service with Mexico and in 2016 removed visa requirements for Mexicans arriving for short-term study visits of up to six months. Mexico is also a top priority country of Canada’s internationalization strategy. Aside from ELT, governments and universities on both sides have recently taken steps to boost student mobility in academic programs, including new scholarship programs and bilateral research agreements. Overall, Canadian universities anticipate strongly rising student inflows from Mexico in the near future. As one Canadian educator told the PIE News, “Canada has always been popular, but we have always had to compete with the United States; that is now changing due to the ‘Trump effect.’”

Inbound Student Mobility

The number of international students who view Mexico as an education destination is comparatively small, but the country recently witnessed a marked uptick in student inflows despite recurring media reports of kidnappings, violence, and corruption. According to UIS data, the number of international students in the country doubled to 25,125 between 2016 and 2017. It should be noted, however, that actual gains may be smaller: Data provided by Mexican statistical agencies, such as Patlani, differ significantly, and data on Mexican mobile students may be incomplete, including for certain years. That said, the agency data also reflect increases in international student inflows. According to Patlani, there were 20,322 international students in Mexico in 2015/16, compared with 15,608 in 2014/15. Most of them studied at the undergraduate level; slightly more than half enrolled in degree programs while the rest attended short-term courses.

The top three sending countries, according to Patlani, were the U.S., Colombia, and France. Whereas fewer Mexican students are going to the U.S., student flows in the other direction appear to be on the rise. While the total number of U.S. students in Mexico is much lower than it was a decade ago, IIE reports that U.S. student enrollments in Mexican short-term study abroad programs increased by 9.9 percent and 10.8 percent in 2015/16 and 2016/17, respectively. These data indicate that there were 5,736 U.S. short-term students in Mexico in 2016/17, making Mexico the 12th most popular study abroad destination worldwide among U.S. students. And Mexico is not only a popular destination for study abroad programs, but also for degree-seeking students from the United States. Per UIS, 44 percent of all international degree students in Mexico (11,109 students) came from the U.S. in 2017. Data for 2016 and other recent years are unavailable.

In Brief: Mexico’s Education System

Education in Mexico was historically influenced by the Catholic church, which provided education during the colonial era. In 1551 the church established the first university in North America, the Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico, in Mexico City. But Catholic education was mainly reserved for the aristocracy, clergy, and other ruling elites, while most of the indigenous population learned by way of oral tradition. It was not before independence and the formation of a modern state that Mexico’s government began to slowly establish tighter control over education and form a modern system that would address the needs of the broader segments of society. In the 19th century, compulsory education for children between the ages of 7 and 15 was introduced, and education became increasingly secularized. After the Mexican revolution (1910 to 1920), Mexican authorities focused on eradicating illiteracy and on advancing rural education and the inclusion of indigenous peoples. However, forming a national identity through education has been a challenge. Choosing Spanish as the language of instruction, for instance, resulted in high illiteracy and desertion rates among indigenous peoples—a circumstance that caused the introduction of bilingual programs in recent decades.

While educational participation rates in Mexico are still low compared with those of other major Latin American countries, Mexico’s education system has since expanded rapidly. Illiteracy rates among the population over the age of 15 decreased from 82 percent at the end of the 19th century to less than 5 percent today. Between 1950 and 2018, enrollments in the formal education system—elementary through graduate education—grew more than 12-fold, from three million to 36.4 million students. The tertiary growth enrollment ratio (GER) jumped from 15 percent in 1990 to 38 percent in 2017 (UIS).

The upper-secondary GER, likewise, has doubled since the 1990s, but disparities persist between more affluent jurisdictions and poorer states. Per Mexican government data, 64 percent of the population between the ages of 20 and 24 had completed upper-secondary education in Mexico City, but only 40 percent did so in Chiapas. While states like Aguascalientes, Mexico City, Nuevo León, Sinaloa, and Sonora have tertiary enrollment rates above 40 percent, these rates are below 20 percent in Chiapas, Guerrero, and Oaxaca. The contrast is starkest between Mexico City, where the enrollment rate reached 72 percent in 2017, and Chiapas, where it stood at merely 14 percent.

Administration of the Education System

Officially called the United Mexican States, Mexico is a federal state that comprises 32 regions that are also called states (including the city of Mexico, an autonomous federal entity). The administration of its education system is the shared responsibility of the national ministry of education, Secretaria de Educación Pública (SEP), and the 32 state-level jurisdictions. Autonomous higher education institutions (HEIs) like the National Autonomous University of Mexico also play an important oversight role. These mostly large public universities operate with a high degree of freedom from government regulations and have the right to approve and validate programs of private HEIs and upper-secondary schools. Autonomous institutions act as de facto educational authorities in that they grant official recognition to other institutions in a similar way as government authorities.

Since 1992, Mexico has decentralized its education system and limited the role of the central government in education. Under financial strain, the federal government gradually transferred the administration of more schools to the state governments and granted autonomy to more HEIs. The percentage of students enrolled in HEIs administered at the state level recently increased from 14 percent in 2008/09 to 21 percent in 2017/18, while only 13 percent study at institutions administered by the federal government. Thirty-six percent of students are enrolled in autonomous institutions, and the remaining 30 percent in private institutions. Autonomous HEIs and their affiliated institutions play only a marginal role in elementary and lower-secondary education, but they enroll 12 percent of upper-secondary students.

This multiplicity of quality assurance providers in the Mexican federation results in a highly complex system in which various quality standards, academic calendars, and regulations coexist not only between states, but also within states, regions, and urban and rural areas. Upper-secondary school curricula, for example, can vary significantly between states and institutions, notwithstanding recent efforts by the federal government to standardize curricula across the nation (see the upper-secondary education section). Elementary and lower secondary curricula are set by the state and federal governments.

Structure of the Education System

Mexico’s education law defines three main levels of education: basic education (educación básica), upper- secondary education (educación media superior), and higher education (educación superior). Each level of education is further subdivided as follows:

- Educación Basica (Basic Education)

- Educación Preescolar (early childhood education): Ages 3–6

- Educación Primaria(elementary education): Grades 1–6

- Educación Secundaria(lower-secondary education): Grades 7–9

- Educación Média Superior (Upper Secondary Education): Typically grades 10–12

- Bachillerato General (general academic)

- Bachillerato Tecnológico (technological education)

- Profesional Técnico (vocational and technical education)

- Educación Superior (Higher Education)

- Técnico Superior (post-secondary/associate/diploma)

- Licenciatura (undergraduate and first professional degrees)

- Postgrado (graduate/postgraduate education)

Preschool Education

Since the 2008/09 academic year, all Mexican children are required by law to attend three years of early childhood education (educación preescolar) beginning at the age of three. This is a gradual increase from previous years when preschool education was either not compulsory or limited to one or two years.3 Before the enactment of these recent reforms, state governments ran a variety of different early childhood programs alongside private institutions with little or no governmental regulation or supervision. However, the provision of preschool education was patchy and limited to mostly urban areas until the decentralization of the Mexican education system in 1992.

Because of the new requirements and major investments in infrastructure and human resources, the early childhood education sector experienced the largest enrollment increases of all sectors since the 1990s. In 2017/18, 4.9 million children attended preschool, an increase of 42.5 percent over 2001/02 when only 3.4 million children benefitted from this form of schooling. Private schools are now more closely regulated, but enroll only 15 percent of children, while 85 percent of children attend public institutions. The majority (88 percent) of children are enrolled in general schools, whereas 8 percent attend special schools for indigenous peoples that provide intercultural bilingual education. Another 3 percent attend special community schools located in rural districts of less than 500 inhabitants. The national pre-elementary GER stood at 72 percent in 2017 (UIS).

Elementary Education

Public elementary education is supervised by the SEP in coordination with the state governments which administer the majority of schools (accounting for 85 percent of enrollments). Schools under the direct control of the federal government account for only 5.5 percent of enrollments, mostly in Mexico City and in rural community schools. But the SEP sets nationwide standards and curricula for both public and private institutions (which enroll close to 10 percent of pupils). The SEP determines school calendars, designs and distributes free textbooks, and oversees teacher training. Until 2019, the now decommissioned federal National Institute for Assessment of Education (INEE) monitored quality standards in schools and collected education data. It is presently unclear if and how the new AMLO administration wants to replace the institute, and critics are concerned that the absence of INEE monitoring and objective data gathering will be detrimental to educational quality.

Elementary education is six years in length (grades one through six) in all states. Children generally enter at the age of six, although there are options for students over the age of 15 who did not complete their education. Most pupils enroll in general schools, but about 6 percent study a bicultural (indigenous) and bilingual curriculum. Close to 1 percent attend community programs (cursos comunitarios), which are offered in rural districts of less than 100 inhabitants.

The national curriculum includes Spanish, mathematics, social studies, natural sciences, civics, arts, and physical education. Each class is assigned one teacher that instructs all subjects throughout the year. Teachers rotate in each grade, although teachers in community programs may stay with one group of pupils for several years. Upon completing grade six, pupils are awarded the Certificate of Primary Education (Certificado de Educación Primaria). There are no final graduation examinations.

As noted before, elementary education is the only sector of Mexico’s education system in which enrollments have decreased—from 14.7 million in 2007/2008 to 14 million in 2017/18. While participation is nearly universal and dropout rates are close to zero in states like Querétaro, Quintana Roo, and Nuevo León, the situation in impoverished rural states is more problematic. Close to 12 percent of pupils in the southern state of Oaxaca, for instance, do not complete elementary school. What’s more, spending on elementary education is far below the OECD average, and many observers consider elementary education in Mexico to be of lackluster quality. The World Economic Forum ranked Mexico’s educational quality at the elementary level 69th out of 130 countries (behind Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Colombia, and Peru, but ahead of Brazil, Ecuador, and Venezuela). Mexico ranked 58th out of 72 countries in the 2015 OECD PISA study, making it the worst-performing country among all OECD member states.

Lower-Secondary Education (Educación Secundaria)

Lower-secondary education is three years in length (grades seven through nine) and was made compulsory in 1992—a change that helped boost enrollments from 4.1 million in 1991/92 to 6.5 million in 2017/18. There are no entrance examinations at public schools, and close to 98 percent of pupils who complete elementary education go on to lower-secondary education. It’s important to note that in Mexico educación secundaria always refers to lower-secondary education and not upper-secondary education (unlike in some other Latin American countries). Secondary schools have different names; they may be called colegios, escuelas, or institutos.

Lower-secondary programs are offered in a general academic track (secundaria general), and a vocational-technical track (secundaria técnica). Before upper-secondary education was made mandatory, the vocational track was designed to prepare students for both upper-secondary education as well as employment in industry, commercial fields, agriculture, or forestry. Both programs have a mandatory general academic core curriculum set by the SEP that includes Spanish, mathematics, biology, chemistry, physics, history, civics, geography, arts, and a foreign language. English was recently made a compulsory subject. Mexican states may also have individual “state subjects,” which focus on historical, cultural, or environmental aspects that are specific to the local jurisdiction.

In addition to standard general academic and vocational programs, there are distance learning programs (telesecundaria) designed to bring education to far-flung rural communities via television, videotapes, or the internet. Very small numbers of students are also enrolled in in-classroom community programs (secundaria comunitaria) and programs for working adults (secundaria para trabajadores). Learning conditions in distance and community education programs are usually more challenging, and dropout rates are higher. While there are designated teachers for each subject in the other types of schools, curricula in these programs are often taught by a single instructor for all subjects.

Slightly more than half of lower-secondary students currently study in general academic programs, while 27 percent attend vocational programs, and 21 percent study in distance education mode. Graduates from all programs are awarded the Certificate of Secondary Education (Certificado de Educación Secundaria). There are no graduation examinations.

As in other stages of education, lower-secondary participation rates vary widely between states and ethnic groups. Marginalized regions still have inadequate infrastructure and resources. Whereas graduation rates topped 90 percent in the industrialized states of Baja California Sur and Hidalgo in 2017/18, that number did not exceed 76 percent in Michoacán. Overall lower-secondary enrollment ratios in rural regions and indigenous communities trail those of urban areas and other social groups by significant margins.

Upper-Secondary Education (Educación Média Superior)

Upper-secondary education lasts three years (grades 10 to 12), although some vocational programs and those offered by autonomous institutions may be from two to four years in length. It’s free of charge at public schools and has been compulsory for all students since 2012. Enrollments are higher in urban areas, but nationwide student numbers have nearly doubled over the last two decades, from 2.7 million in 1997/98 to 5.2 million in 2017/18.

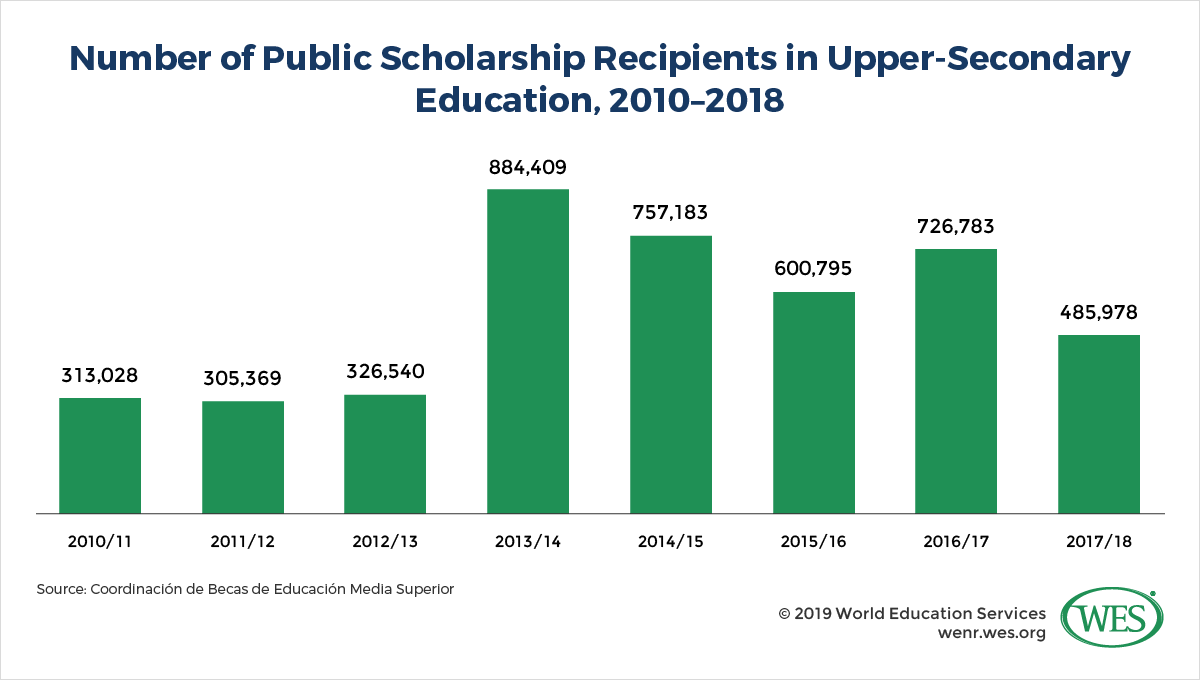

Making upper-secondary education universal will remain a challenge for years to come, however. While SEP data show that nearly all students who complete lower-secondary education enroll in upper-secondary school, the nationwide graduation rate is currently just 67 percent. Merely 20 percent of students from households in the lowest income bracket complete upper-secondary school. To increase graduation rates, the Mexican government provides scholarships to many students. However, after increases in spending for these scholarships in previous years, funding has recently been scaled back. Since 2016 the number of recipients has decreased by more than 240,000. The government recently acknowledged that achieving universal participation in upper secondary education might take two decades longer than originally anticipated.

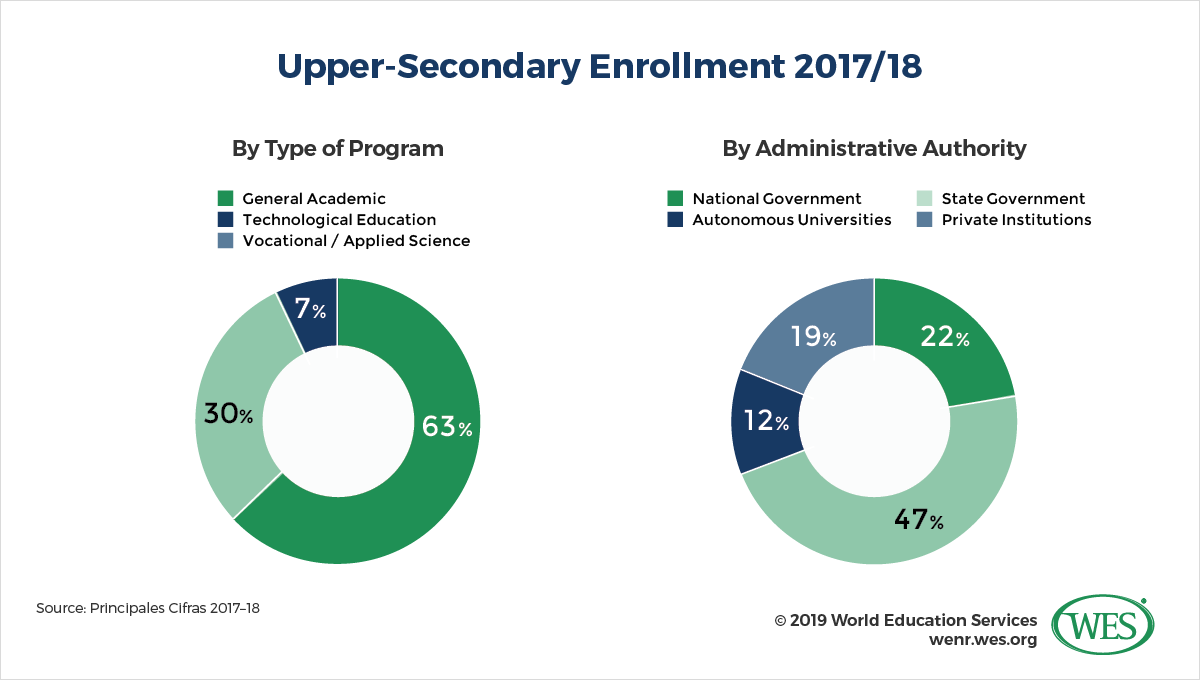

High schools are administered by the federal government, state governments, and autonomous institutions, which, as mentioned earlier, are mostly large public universities. Autonomous universities that provide upper-secondary education can independently design their own curricula. Admission to these programs frequently involves entrance examinations and is often more competitive than admission to state and federal schools. Many students that complete upper secondary education at an autonomous university continue their studies in higher education programs at the same institution. Around 12 percent of all upper-secondary students currently study in such programs, while 47 percent study at state schools and 21.5 percent enroll at federal schools. Some 19 percent attend private schools, which are located mostly in larger cities and include religious and international schools. Since the private schools charge tuition fees, many of them are better equipped and provide high-quality education, but they are usually out of reach for low-income households.

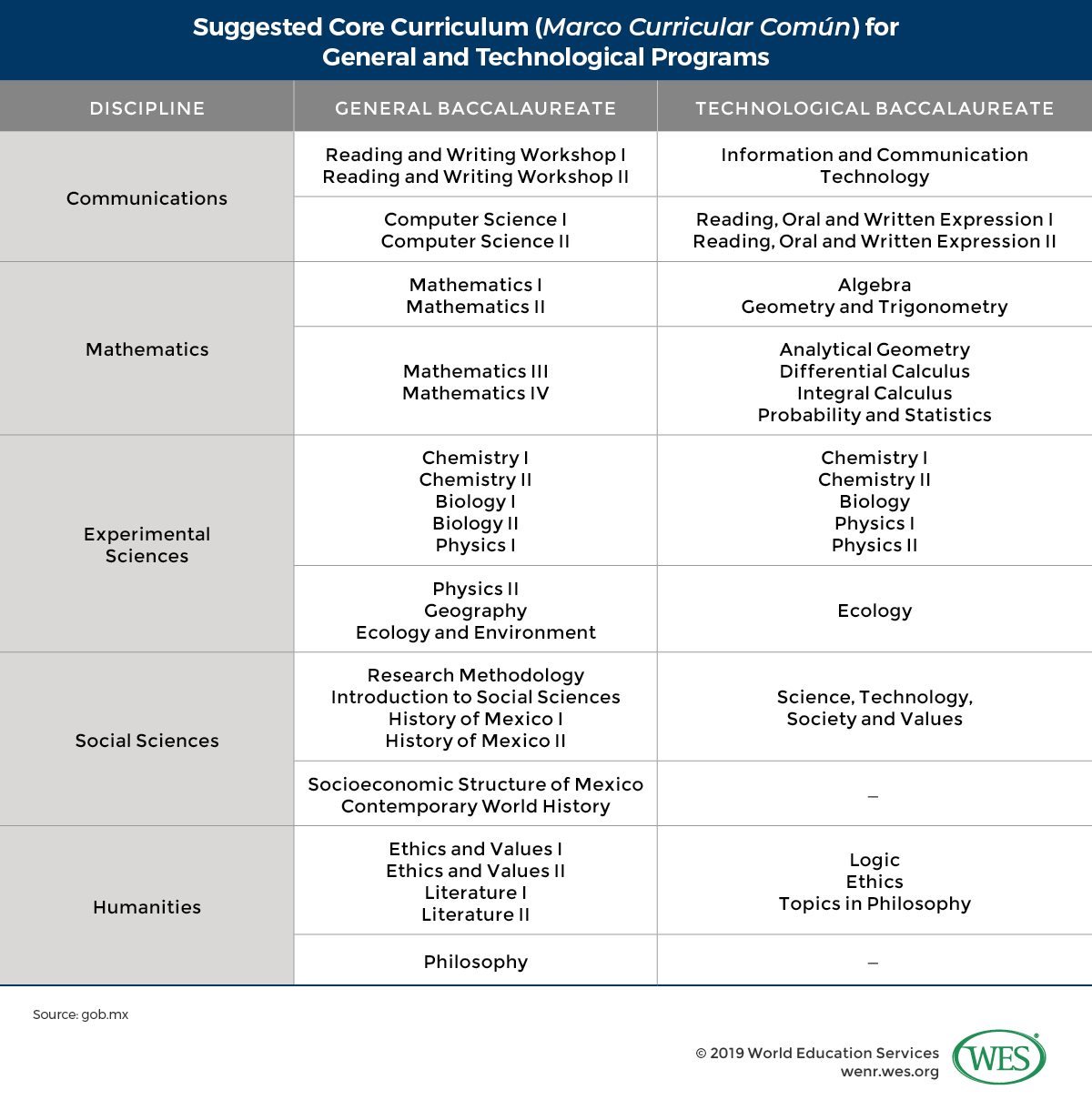

Given the multiplicity of providers and curricula in Mexico, its upper-secondary school system has been characterized by a high degree of diversity and fragmentation. It was historically perhaps the most heterogeneous system in Latin America—a circumstance that complicated the mutual recognition of credentials and the transfer of students between programs. However, the federal government in 2008 introduced a national curriculum framework (marco curricular común) and high school system (sistema nacional de bachillerato) in order to harmonize upper-secondary education. The system defines desired learning outcomes in mathematics, Spanish, English, biology, chemistry, physics, geography, history, and economics. While its adoption is voluntary, 4,284 Mexican schools enrolling 52 percent of students have implemented the system as of 2019, and more are expected to join. It should be noted, however, that distance learning and community high schools (telebachillerato comunitario) and other types of schools continue to use different curricula, so a certain degree of heterogeneity will persist in Mexico’s system despite the reforms.

There are three main types of upper-secondary programs: general academic (bachillerato general), technological (bachillerato tecnológico), and vocational-technical (técnico profesional). Most students (63 percent) enroll in a general academic program, while 30 percent study in the technological stream. The remainder attend vocational-technical programs.

Bachillerato General (General Academic)

General academic programs are designed to prepare students for higher education. Admission requires the Certificado de Educación Secundaria as well as entrance examinations, depending on the program. The curriculum comprises general subjects, including those of the marco curricular común, but students usually specialize in sciences or social sciences in their final year. English is compulsory. The formal credential awarded upon completion of this stage is the Certificado de Bachillerato, but it should be noted that graduates do not always receive a graduation certificate. Instead, they may simply get an academic transcript (Certificado de Estudios) indicating that they have completed the bachillerato program or university-preparatory studies (preparatoria). The same holds true for technological programs that incorporate university preparatory studies.

Bachillerato Tecnológico (Technological)

Technological high school programs feature a general academic core curriculum. It is very similar to Bachillerato General programs in addition to several employment-geared technical specialization subjects in fields like agricultural technology, business, computer science, industrial technology, marine technology, nursing, or tourism. The curriculum is designed primarily by the federal government, as well as by state governments which may offer specializations relevant to local industry. Because of different curricula in individual jurisdictions, there’s often an overlap between Bachillerato Tecnológico and Técnico Profesional programs that are offered in different states in fields like accounting, business, computer science, or nursing. Technological programs provide access to higher education in the same way as general academic programs.

Vocational and Technical Education (Educación Profesional Técnica)

There are two types of upper-secondary vocational credentials in Mexico: the Título de Técnico Profesional (title of professional technician) and the Profesional Técnico Bachiller (professional technical bachelor). Both types of programs were initially designed as terminal programs preparing graduates for entry into the labor market—graduates receive a cédula profesional (professional license) in specific vocations. However, since 1997, graduates have also been officially eligible for admission to post-secondary degree programs. That said, the level of articulation with higher education in the applied vocational programs is lower than in other upper-secondary programs, and most graduates join the labor force rather than enroll in higher education. Most holders of the Profesional Técnico Bachiller awarded by private schools do not continue on to higher education. Many graduates are from households of lower socioeconomic status.

The main oversight body in vocational education is the National College for Technical and Professional Education (Colegio Nacional de Educación Profesional Técnica, or CONALEP), which functions as a federal regulatory authority while it’s simultaneously a large network of schools. Most vocational schools, however, are funded by the state governments.

Vocational specializations differ by state and include fields like accounting, construction, electronics, information technology, mechatronics, optometry, refrigeration technology, or tourism. Overall, there are about 50 different specializations on offer in different parts of Mexico.4 The trend is toward the national standardization of programs and a reduction in the number of specializations. All programs have a general academic core component that has been expanded since the introduction of the new national high school system. Beyond that, curricula are applied rather than theoretical, and commonly include industrial internships, as well as a social service requirement mandated by law. During the non-paid social service— usually completed in the second half of the program—students are expected to apply their acquired skills for the benefit of the community. Upon completion of the program, graduates in most specializations are granted both a high school credential and a professional license (Cédula Profesional) that entitles them to work in regulated vocations.

Higher Education

Mexico’s higher education system has grown rapidly, if unevenly, over the past decades. According to Mexican government data, tertiary enrollments have more than doubled since the late 1990s. There are presently 3.9 million tertiary students enrolled in regular programs, and another 696,000 studying in distance education mode (up from 125,000 in 1997/98). However, as in all parts of Mexico’s education system, enrollment gains are heavily skewed toward wealthier states. Tertiary enrollment ratios in Chiapas, for instance, are fully 60 percent below those of Mexico City.

There are more than 3,800 degree-granting HEIs with over 7,400 connected teaching institutions in Mexico. Many new private providers have sprung up across the country in recent years. Their number now exceeds that of public providers by a wide margin. However, enrollments are primarily concentrated in the public sector—unlike in other Latin American countries. In Chile, for instance, private enrollments now outnumber those at public HEIs. The reason is, Mexico’s public autonomous universities and state and federal institutions have expanded their capacities at a slightly faster clip than smaller private HEIs. As of 2017/18, 30 percent of tertiary students studied at private institutions (down from 33 percent in 2009), while 70 percent attended public HEIs. Autonomous institutions enroll 36 percent of tertiary students; state institutions, 21 percent; and federal institutions, 13 percent.

Mexico’s tertiary system is characterized by disparities in quality between HEIs. Oversight criteria for private HEIs vary by jurisdiction and are often inadequate. As a result, the private sector features only a small number of prestigious top-quality institutions, while a substantial cohort of newer upstart schools seek to absorb demand without much regard for either academic standards or student outcomes. These for-profit schools cater mostly to students who are unable to access public institutions because of enrollment quotas and competitive entrance examinations. However, given the decentralized nature of quality assurance in Mexico, disparities in quality also exist between public HEIs.

The top Mexican institutions included in international university rankings include the National Autonomous University of Mexico and the private Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Education, both ranked in the 601–800 range in the current Times Higher Education World University Rankings and featured among the top universities in Latin America. Other reputable HEIs include the Metropolitan Autonomous University, the Autonomous University of Querétaro, the Instituto Politécnico Nacional, and Universidad Anáhuac.

Types of HEIs

HEIs in Mexico include public and private institutions. Public institutions encompass various different types, such as federal universities, state universities, large numbers of technical universities and technical institutes (institutos tecnológicos), and polytechnic universities, as well as teacher training colleges, dedicated research centers, and 13 intercultural universities (universidades interculturales) for indigenous peoples, along with various HEIs overseen by other government entities like the military. So-called state universities with solidarity support (universidades públicas estatales con apoyo solidario) are a group of 23 state universities that receive special funding from the federal government. They are designed to educate underserved populations in marginalized regions. There’s also a large public open and distance education university, the Universidad Abierta y a Distancia de México.

Autonomous HEIs

While autonomous HEIs are publicly funded, these institutions enjoy a high degree of academic and administrative freedom. Many of them independently supervise private HEIs and validate programs offered by private providers in both higher and upper-secondary education. Each state in Mexico except for Quintana Roo has at least one autonomous university, often located in the state capital. The largest autonomous HEIs are the Universidad Nacional Autonóma de México with about 243,000 students, the Universidad de Guadalajara, and the Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León with some 130,000 students each. These institutions are also the largest higher education providers in Mexico. Upper-secondary schools administered by autonomous universities tend to have much larger enrollments by school than state schools as well (1,200 versus 300, on average).

Most of the larger autonomous institutions were granted autonomy between the 1920s and the 1970s and have facilitated social mobility for generations of students, mostly in large urban centers. Only a few smaller institutions have been granted autonomy since the 1970s. Overall, most autonomous institutions are reputable universities with a long tradition of research and innovation. They also tend to perform better in national and international rankings compared with other Mexican HEIs. In 2017/18, autonomous institutions administered a total of 1,237 school units with 1.4 million students, and had a combined faculty of more than 133,600.

State HEIs

State HEIs encompass various types of institutions including regular universities, polytechnic universities, and technical institutes. They operate under the auspices of the state governments, which appoint their leadership staff and determine the structure and content of academic programs. Many of them are in less populated rural areas, where they may be the only higher education providers within reach. While state universities vary in size, they usually have fewer students than autonomous institutions (just a fourth of enrollment numbers, on average). Nevertheless, some state governments have invested heavily in education in recent years and expanded both the capacity and the number of HEIs. Between 2008/09 and 2017/18, nationwide enrollments in state HEIs more than doubled, from 374,000 to 800,000 students.

In general, state HEIs tend to serve less affluent students when compared with other types of institutions. Most are in small cities and rural areas, where they provide virtually tuition-free education to vulnerable groups. Their quality varies. Some state universities are well-funded, high-quality providers housed in modern facilities that produce graduates who have good employment prospects, but others are poorly equipped and isolated. They collaborate little with other HEIs or industry, and their enrollments are low. Critics have observed that several of these institutions were planned without proper needs assessments, even though they represent an effort to expand access to underserved populations.

Federal HEIs

Federal HEIs are overseen and primarily funded by SEP and other federal government agencies. They represent a relatively small but diverse group of institutions in terms of size, physical location, programs, and academic quality. The socioeconomic composition of the student body in Mexico City—where more than half of all students attending federal universities are enrolled—is comparable to that of autonomous universities, but it resembles that of state HEIs in other provinces. Overall, 511,000 Mexicans studied at federal HEIs in 2017/18.

Until recently, the Instituto Politécnico Nacional was the largest of these providers, enrolling roughly 120,000 students. However, in 2014 the Mexican government created an even larger federal institution when it merged 266 public technical institutes into the new Tecnológico Nacional de México. Other federal HEIs include research centers of the National Council of Science and Technology, a number of intercultural and technological universities, as well as a few teacher training colleges and institutions run by the military, the justice department, the ministry of health, and other government bodies. On average, federal HEIs are larger than state institutions, in part because they have been in existence for a longer time, and many are located in Mexico City.

Unlike autonomous institutions, federal institutions are tightly regulated by federal authorities, so that changes in government can have far-reaching implications for their administration, staffing, and study programs. The Mexican Congress could technically grant autonomy to institutions like the Instituto Politécnico Nacional, but there’s a contentious debate regarding this issue. Critics of the federal university system argue that government control is detrimental to academic quality and turns higher education into a political football. Others contend that it is the very role of the Mexican state to shape higher education and seek to increase political control even over institutions that already have autonomy. Since the early 1990s, the federal government has increasingly withdrawn from directly administering HEIs and transferred the oversight of many teacher training colleges, technical institutes, and others to state governments, or granted these institutions autonomy. The relative share of students enrolled in federal HEIs has decreased because of this process.

Private HEIs

This group includes the largest and most diverse number of schools. On one side of the spectrum are well-established, high-quality elite providers like the Tecnológico de Monterrey, the Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México, Universidad de las Américas Puebla, Universidad Iberoamericana, Universidad Anáhuac, Universidad Panamericana, and a few others. On the other side are many small and new for-profit institutions of lesser quality. Whereas annual tuition fees at public universities are relatively low (USD$378 to USD$818), private HEIs charge fees of anywhere between USD$1,636 and USD$16,353 per annum. The fees charged reportedly have little to do with the quality of education offered.

Although the relative percentage of enrollments in private institutions has decreased over the last decade, the actual number of students has increased from 897,800 to 1.15 million since 2009. What’s more, the number of private HEIs has simultaneously doubled to more than 3,000. This expansion is driven by a growing number of Mexican middle-income households that can pay for private education, among other factors. Students from low-income households typically only attend private HEIs if they can secure scholarship funding or student loans.

Given capacity limits at public HEIs, private institutions enable more Mexicans to participate in higher education. However, the rapid spread of small private providers, some of them offering only a handful of programs, has strained the capacity of Mexican authorities to provide effective quality control—a problem exacerbated by the mushrooming of hybrid and distance learning programs. Without generalizing, lax quality assurance mechanisms in a number of states have allowed some providers of dubious quality to operate in Mexico. As a result, the growth of private education in Mexico is a trade-off between boosting enrollment ratios and improving quality standards. Some state governments have curbed private education and revoked the recognition of questionable providers, while others have opened the gates to untested transnational distance education programs. There’s presently no national consensus on how to address the quality assurance of private institutions.

Private HEIs can obtain authorization and recognition of their degree programs from the SEP at the national level, or from state departments of education. They can also seek validation from or incorporation into autonomous universities. It should be noted, however, that not all autonomous universities validate private programs, and that some have very strict requirements. In most cases, private institutions are authorized and recognized by state governments. A small number of top institutions have been designated as “free” (libre)—a prestigious status that exempts HEIs from several requirements and can only be conferred by the president of Mexico. There are also some unregulated private HEIs, including religious institutions, that operate outside of Mexico’s formal system of education.

Quality Assurance

All officially recognized HEIs in Mexico are conferred a Reconocimiento de Validez Oficial de Estudios (RVOE, or recognition of official validity of studies) by the federal government or state governments. While autonomous universities and government institutions are automatically recognized, private institutions must in most cases be authorized by government authorities to obtain the RVOE. They must have adequate facilities and teaching staff, submit a self-assessment, and get approval of their study programs from the federal Comisión Nacional de Evaluación para la Educación Superior (CONAEVA).

RVOEs are issued for each individual program of study. While private institutions may issue their own degree certificates and academic transcripts, they are by law required to display the RVOE on their academic records. RVOE status can be verified in an online registry. Some degree certificates and transcripts may also bear the seal or signature of the government agency that oversees the institutions that issue the. Alternatively, private HEIs may be affiliated with public autonomous universities by incorporación. In this case, degree-granting authority resides with the autonomous university with which the incorporated institution is affiliated.

Both public and private HEIs can also seek voluntary accreditation of their programs by agencies under the El Consejo para la Acreditación de la Educación Superior, A.C. (COPAES, the Higher Education Accreditation Council). Established in 2000 to improve quality standards nationwide, COPAES is an independent, private nonprofit organization that oversees 30 smaller programmatic accrediting bodies in different disciplines, such as social sciences, law, or medicine. Those accrediting bodies then accredit undergraduate programs, designating them to be of “good quality” (buena calidad) if successful. Institutions are required to reapply for reaccreditation of their programs every five years. Accredited programs enjoy higher academic prestige both nationally and internationally, and are eligible for additional governmental financial support and grants. As of February 2019, COPAES accredited 3,962 study programs, accounting for 47 percent of all undergraduate enrollment in higher education.

Graduate programs are assessed by the National Council for Science and Technology (Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología, or CONACYT). CONAYCT evaluates especialista, maestría, and doctorado programs (see below). Those that meet the minimum standard are designated programas de posgrado de excelencia (graduate programs of excellence) and listed on the National Registry of Graduate Studies (Padrón del Programa Nacional de Posgrados de Calidad or PNPC). Programs are classified as either “High Level” (Alto Nivel) or “Competent on an International Level” (Competencia Internacional).

Note that only few private institutions apply for accreditation or submit their programs for voluntary quality assurance audits. Less than 10 percent of private HEIs have official accreditation for their undergraduate programs. However, the overall number of institutions, both public and private, that offer accredited programs has doubled over the past decade, and 64.5 percent of undergraduate students at public institutions study in accredited programs, but wide disparities persist between states and regions.

Admission to Higher Education

Admission criteria at Mexican HEIs vary greatly, depending on the program and demand. Completion of upper-secondary education is usually the minimum criterion, but entrance examinations and high school GPAs are typically used to select students. Many universities require a minimum grade average of 7 or 8 out of 10, but top institutions may require a higher minimum. Certain university departments may also require that students have completed high school programs in a track related to the program of study.

In addition, some less selective institutions have open enrollment policies. Older students who did not complete high school may gain admission into federal HEIs by taking a national high school equivalency exam. However, most large universities that are not administered by the federal government, including private autonomous universities, have their own admissions tests. There’s a national higher education entrance examination called EXANI-II, but while growing numbers of HEIs are admitting students based on this exam, it’s presently used only for certain programs. The number of students sitting for the exam has increased from about 419,000 in 2006 to 740,000 in 2017. Some universities may also use a Spanish version of secondary school examinations designed by the College Board, which in the U.S. are used as a kind of admissions examination.

Credit System and Grading Scale

There’s no nationwide credit system in Mexico, and not all Mexican HEIs, particularly private ones, indicate credits on their academic transcripts. However, Mexico’s Association of Universities and Higher Education Institutions (ANUIES) in 2007 put forward a credit system called SATCA (Sistema de Asignación y Transferencia de Créditos Académicos). This system defines one credit unit as 20 hours of “learning activities,” and determines the minimum number of credits required for a licenciatura program as ranging from 180 to 280 credits, depending on the length. However, it should be noted that the new system is being implemented only slowly, and that not all public institutions use it. Autonomous universities most commonly use a scale that defines a credit as one hour of classroom instruction over the course of a semester.

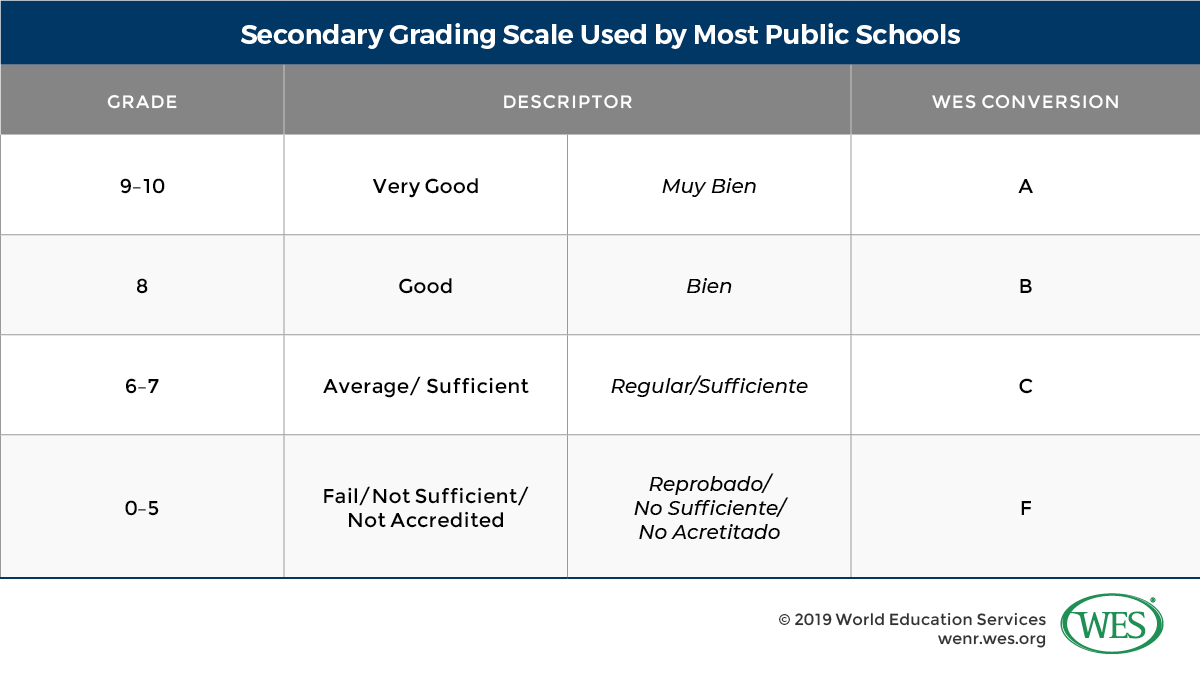

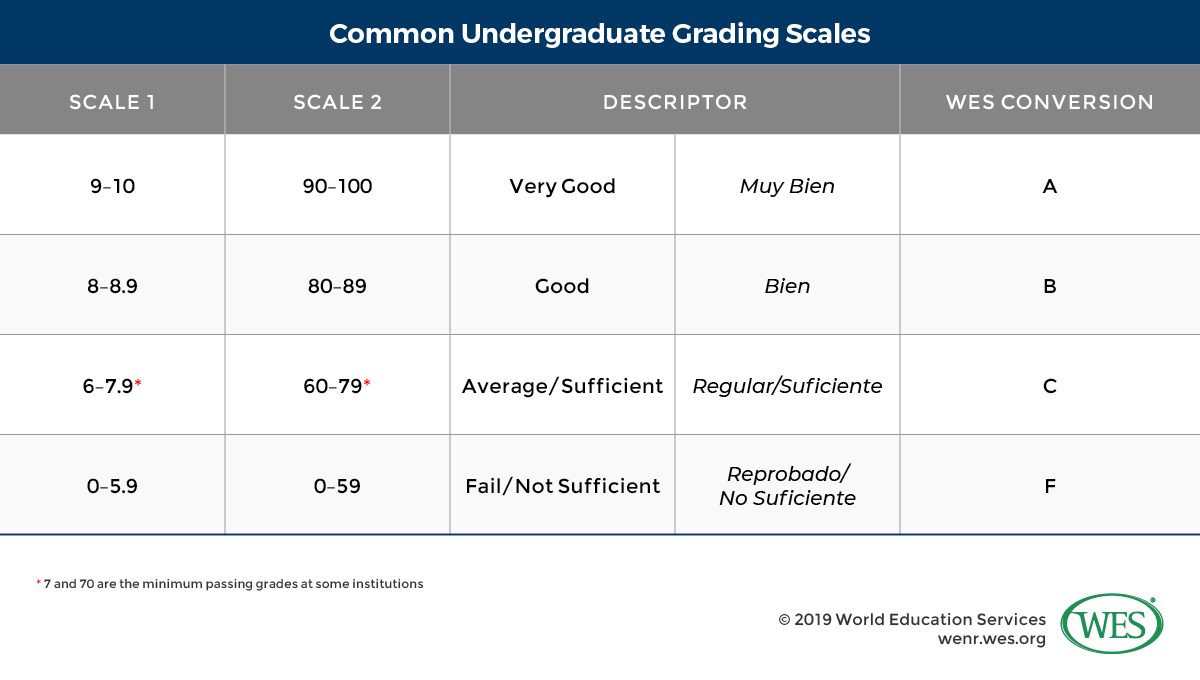

Grading scales vary between HEIs as well. The table below shows three commonly used scales, including the WES conversion. Seven is the passing grade on many undergraduate scales, but a grade of 8 may be the passing score at the graduate level.

The Higher Education Degree Structure

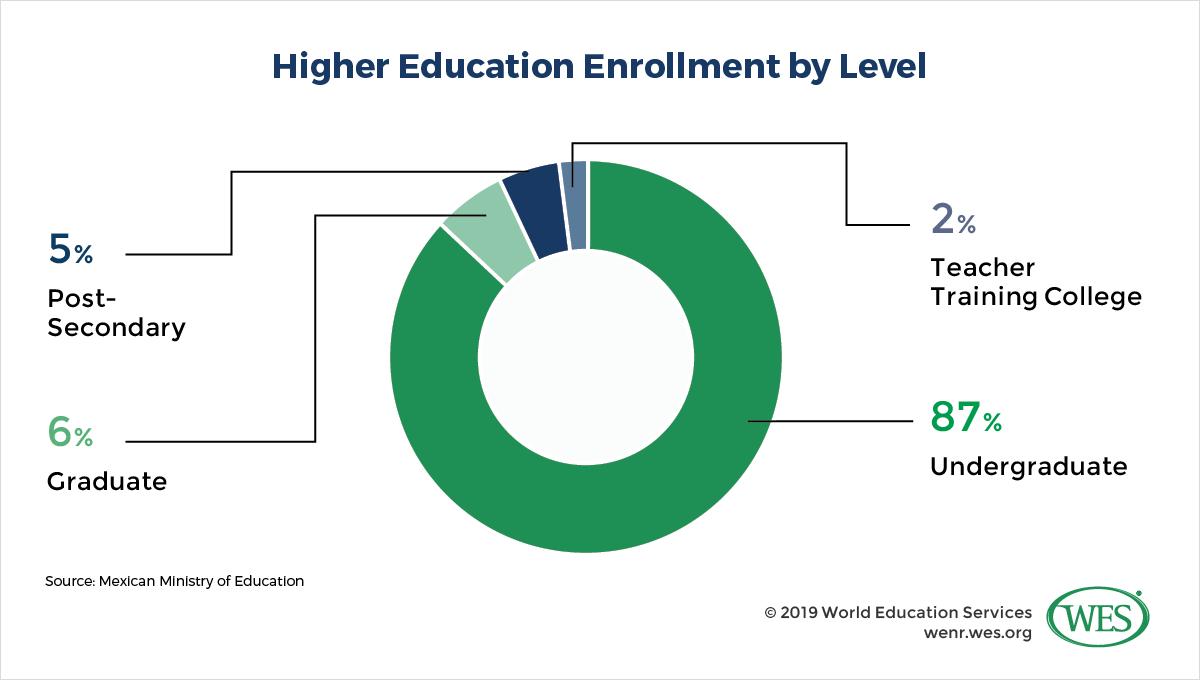

Degrees awarded in Mexico include shorter associate degree-type qualifications, bachelor’s degrees (licenciatura), master’s, and doctoral degrees. Most Mexican students are enrolled at the undergraduate level—89 percent studied in licenciatura programs, including teacher training programs, in 2017/18. Only 6 percent studied at the graduate level, and less than 5 percent in post-secondary associate programs.

Associate Degree (Técnico Superior Universitario/Profesional Asociado)

Shorter vocational-technical programs at the post-secondary level are relatively new in Mexico. These programs are offered mainly by universidades tecnológicas and typically last two years, although some three-year programs also exist. They require 75 to 120 credits at HEIs that use the SATCA credit system. Curricula are employment-geared and as such are applied in nature: Only 30 percent focus on theoretical instruction, and 70 percent on practical instruction and projects. Until the appearance of the technical universities, most vocational-technical programs were offered either at the upper-secondary level or, very rarely, in longer four- or five-year university degree programs.

The final credential awarded is called the Técnico Superior Universitario (university higher technician) or Profesional Asociado (professional associate). While many of these programs are considered terminal qualifications designed for employment, they may also grant advanced placement in higher licenciatura or titulo profesional programs, depending on the institution. There are presently only 273 schools in Mexico offering associate-type programs, most of them state HEIs. Programs are offered in a variety of specializations, such as allied health, business administration, information technology, transportation, or tourism.

Certificado/Diplomado Programs

Other short, applied programs lead to a certificado or diploma. These certificate-level programs run from one to three semesters, while so-called salida lateral (lateral exit) programs can last up to four years and may sometimes account for the first one or two years of a licenciatura or titulo professional program.

Licenciado and Titulo Profesional Degrees

Both the licenciado and titulo professional, terms that are used somewhat interchangeably, are first-degree programs lasting between three and six years. Programs usually include both course work and a thesis or degree project. In general, curricula are specialized and impose few general academic course requirements. Some HEIs offer more U.S.-style curricula.

Programs in professional disciplines like architecture, dentistry, or veterinary science are five years in length. Medicine is a six-year program. Graduates are typically licensed to practice at the point of graduation. Graduates receive a professional license (célula professional) and are entitled to carry an official title, such as Titulo de Abogado (title of lawyer), Titulo de Arquitecto (architect) or Titulo de Ingeniero (engineer). Graduates from all programs are also required to complete a mandatory social service “internship” of at least 480 hours, or up to one year in health-related professions. Given that this internship is unpaid, it affects graduation rates, since some students are unable or unwilling to meet this requirement. According to statistics from ANUIES, only 52 percent of the students that enroll at public institutions complete the entire program and earn a full-fledged degree certificate, while 48 percent either drop out or complete the course work without meeting all the degree requirements. Graduation rates are higher at private institutions and among students from higher income households.

The Carta De Pasante

Students who have completed all their course work but not the thesis or other graduation requirements may receive a certificate called the carta de pasante (leaving certificate), and attain the status of an egresado/pasante. Students who obtain this status do not have a degree, and they do not have the professional privileges in their field of study that are accorded to licenciados (holders of the licenciate degree). However, the carta de pasante may qualify students for conditional admission into graduate school at some institutions.

Although students who earn the classification of egresado/pasante cannot be licensed to practice in their respective profession, they do often find employment in their field of study, often in an auxiliary capacity for the more regulated professions. For example, a student in a law program who has obtained the carta de pasante, but not the licenciatura degree cannot practice as a licensed lawyer, but might be able to work as a paralegal. In other, less regulated industries, such as business administration or engineering, an egresado/pasante might well find a very desirable position without the benefit of the final licenciado degree.

Note: Many HEIs issue students a “diploma” following completion of course work in a program, but before completion of the graduation requirements, and thus before the licenciado degree has been officially awarded. Students may also receive a “diploma por pertenecer a la generación de XXXX” (diploma for belonging to the class of XXXX).

Grado De Maestro (Master’s Degree)

Most commonly two years in length (between 80 and 120 SATCA credits), the maestría program requires the completion of course work and typically a thesis. A bachelor’s degree (Licenciatura/Título Profesional) in a related discipline is usually required for admission.

Participation rates at the graduate level in Mexico are low compared with those of other OECD countries. Tuition fees for graduate programs are considerably higher than for undergraduate programs, which are virtually free at public HEIs. Private HEIs are represented more prominently at the graduate level, accounting for 50 percent of total enrollments.

Graduate programs are offered as research oriented as well as more professionally oriented. The latter tend to be more flexible in terms of delivery and class scheduling, since they are often tailored to working professionals seeking to upgrade their skills. As of May 2019, there were 1,229 master’s programs listed as meeting quality standards in CONACYT’s national registry, although various other programs are offered throughout the country.

Especialista (Specialist)

Another type of shorter postgraduate program are the cursos de especialización. These programs also build on the licentiate degree, but usually have more applied curricula than full-fledged Maestría programs, although some may also constitute the first year of a Maestría. Completion of course work is required; a thesis is generally not. Programs are usually one year in length (at least 45 SATCA credits), but there are also part-time programs that require fewer credits to complete. Graduate medical education programs, which are up to four years in length, are an exception.

Especialista programs generally require a bachelor’s degree for admission, but some HEIs admit undergraduate students who have completed their course work but not yet satisfied the final graduation requirements. In these cases, the first semester of the especialista program may satisfy the graduation requirements in lieu of a thesis, examination, or degree project.

Doctorado (Doctorate)

Doctoral programs are terminal research qualifications that require at least two years of course work as well as original research and the defense of a dissertation. Admission is generally based on a master’s degree in a related discipline, but qualified holders of undergraduate degrees may also be admitted, in which case the programs involve more course work. CONACYT presently lists 653 doctoral programs in its national registry of quality graduate programs. Most are offered by pubic HEIs with autonomous universities being the main providers.

Teacher Education

Teachers are trained at dedicated state-supervised teacher training colleges, the escuelas normales superiores. Teachers at all levels are required to hold a licentiatura-level qualification, which is called the Título Profesional de Educación Normal (Professional Title of Normal Education). Programs are four years in length and require a bachillerato for admission.

Through the SEP the federal government oversees teacher education and determines curricula, assessment standards, and staffing at teacher training colleges. As a result these institutions are often more politicized and influenced by changes in government than other public HEIs. Top level administrators are often appointed and replaced based on political affiliation, and there’s a considerable degree of corruption at these institutions.

A related problem is that teaching standards at these institutions are not always optimal, notwithstanding numerous reforms and efforts to strengthen teacher training over the past two decades. In 2014/15, only 49 percent of graduating students achieved acceptable results in examinations conducted by the National Institute for Educational Evaluation. Given that overall graduation rates at teacher training colleges are high, the poor examination results raise questions about the teaching and graduation standards at teacher training colleges, and erodes public trust in teacher education in Mexico.

WES Documentation Requirements

Secondary Education

- Academic transcripts (certificado de estudios /calificaciones)—sent directly by the institution attended

- Precise, English translation of all documents not issued in English—submitted by the applicant

Higher Education

- Academic transcripts (certificado de estudios /calificaciones)—sent directly by the institution attended

- Photocopy of degree certificate—submitted by the applicant

- For completed doctoral programs, an official letter confirming the conferral of the degree—sent directly by the institution

- Precise, English translation of all documents not issued in English

Sample Documents

Click here for a PDF file of the academic documents referred to below.

- Bachiller (autonomous university)

- Bachiller (private institution)

- Título de Técnico Superior Universitario (state institution)

- Título de Físico (autonomous university)

- Licenciada (private institution)

- Carta de Pasante (autonomous university)

- Grado de Maestro (private institution)

- Título de Doctora (federal institution)

1. UNESCO Data

2. PISA stands for Programme for International Student Assessment.

3. Legislation from 2002 made one year of early childhood education compulsory beginning in the 2004/05 academic year and extended it to two years in 2004/05 and three years in 2008/09. See: https://www.dgespe.sep.gob.mx/public/normatividad/acuerdos/acuerdo_348.pdf

4. As an example, see the specialization on offer in the states of Jalisco and Nuevo León.