Rethinking Institutional Policies to Reduce Barriers Facing Displaced Students in the U.S.

Bryce Loo, Research Manager, WES

Since the current worldwide refugee crisis gained international attention in 2015, there has been increasing coordination among various actors to help displaced students and scholars access higher education. Initial efforts worldwide have largely consisted of discrete initiatives developed by various individual higher education institutions, higher education-serving organizations, governments, private companies, and others.1 But within and across nations, many of these stakeholders have begun coordinating their efforts to further address general and specific barriers, such as the admissions process, tuition and living costs, and language.

One barrier displaced students encounter with some regularity is the inability to access their academic credentials and have them assessed and ultimately recognized. At World Education Services (WES), we have sought to address this barrier through research and advising on best practices in working with displaced students and highly educated professionals. The WES Gateway Program provides credential assessments to students and professionals in Canada who are from certain countries in crisis and have incomplete or unverifiable documentation. Through the WES Gateway Program, WES Global Talent Bridge assists these students and professionals in achieving their educational and career goals.

WES recently joined a number of other U.S.-based organizations to develop a policy paper titled Inclusive Admissions Policies for Displaced and Vulnerable Students. Coordinated by the American Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admissions Officers (AACRAO), a membership-based organization with more than 2,600 affiliated institutions worldwide, this paper provides insight into the broad issue of access within the United States from the points of view of the academy (professors and scholars), displaced scholars and students, and institutions. It zeros in on the barrier of credential evaluation and recognition that arises when students cannot access verifiable documentation.

This article will briefly review the context surrounding the AACRAO policy paper before discussing the main points of the paper itself.

Coordinating Efforts to Address Barriers for Displaced Students

Since its start in 2011, the Syrian civil war has led to more than five million Syrians leaving the country as refugees, disrupting the education of millions of students and overwhelming the countries to which they have fled. The fleeing of thousands from across the Global South, particularly the Middle East and Africa, led to the migration crisis in Europe that began in 2015. The crisis forced individual countries and the European Union to rethink their policies and procedures, including how to integrate vast numbers of refugees and asylum seekers. Language and admissions requirements, financial need, and the limited capacity of local academic institutions to absorb the increased numbers are only some of the barriers that refugees confront if they wish to resume their education. One barrier in particular—gaining recognition for previous academic study when official documentation is not available—is often insurmountable.

In such a decentralized environment as U.S. higher education, coordination and collaboration to reduce barriers are important, if not essential, to offering opportunities for displaced students. In this regard, Europe and Canada have taken greater strides relative to the U.S. Regarding the barrier of qualifications recognition, the most collaborative effort has been the European Qualifications Passport for Refugees (EQPR), a joint effort of the ENIC-NARIC Networks, the Council of Europe, and the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR). This effort is built on the work of individual European countries, particularly that of Norway. Issuing a passport involves assessing candidates’ educational background by reviewing unofficial documentation that refugees and asylum seekers who have entered Europe still have in their possession, as well as professionally conducted interviews.

In late 2015, the newly elected government under Prime Minister Justin Trudeau promised to resettle tens of thousands of Syrian refugees in Canada in just a few months, in part through that country’s private refugee sponsorship system. This effort became a uniquely Canadian project. Large scale mobilization of the government, private companies, organizations, and citizens worked to host and integrate more than 25,000 refugees in a seven-month period.

The Canadian Information Centre for International Credentials (CICIC) began coordinating efforts to have refugees’ credentials recognized across Canada. CICIC, a subset of the Council of Ministers of Education Canada (CMEC), led the Assessing the Qualifications of Refugees initiative. The initiative was funded by the Government of Canada’s Foreign Credential Recognition Program (FCRP), which coordinates the evaluation of international credentials across Canada. In November 2016, CICIC kicked off the initiative by hosting a summit that brought together post-secondary institutions, licensing boards, federal and provincial government officials, and all credential evaluation services from across Canada, along with international experts to discuss the challenge and put forward recommendations, which were outlined in a final report. These stakeholders built on the work of many individual institutions and organizations, including WES’ research on best practices and its pilot project for Syrian refugees (now the WES Gateway Program).

Institutions and organizations in the U.S., by contrast, have lagged somewhat behind their European and Canadian counterparts in rethinking credential evaluation and recognition for the displaced. The difficult social and political climate in the U.S. surrounding immigration plays no small part in their inaction. Some organizations, including credential evaluation services, have put forward discrete initiatives that are noteworthy, though generally small in scale. Individual institutions that have encountered significant numbers of displaced students have developed policies and procedures, often on an ad hoc basis, to address these students’ lack of access to full, official credentials. But there have been few attempts to engage in a national conversation and to develop synergy around the issue.

New Initiatives in the U.S.

Recently, however, there have been nascent efforts in the U.S. to start coordinating and collaborating more to facilitate access to higher education:

- A consortium of scholars, university staff, policy makers, and representatives of nonprofit organizations and NGOs has come together under the umbrella of the University Alliance for Refugees and At-Risk Migrants (UARRM), now housed at Rutgers University. Its purpose is to mobilize the academic community to address the barriers that displaced students encounter, including in the area of documentation.

- The Institute of International Education (IIE), long a supporter of displaced scholars and students, ramped up its efforts in the wake of the Syrian civil war. One of its most recent initiatives, the Platform for Education in Emergencies Response (PEER), is a clearinghouse for educational opportunities for refugees worldwide, including programs, courses, and scholarships. Credential evaluation and recognition are not explicitly part of this initiative, but they are certainly acknowledged barriers to be addressed.

- AACRAO has partnered with the University of California (UC) Davis and the American University of Beirut’s Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs to pilot an initiative known as Article 26 Backpack. Inspired by Article 26 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which states that all have the right to an education, the program allows displaced and migrant students to safely store academic and professional documents on a cloud-based platform. Students can access this virtual “backpack” and send documentation to admissions officers, employers, credential evaluators, and others as needed. The program is run out of UC Davis.

These initial steps are being taken despite the current political climate in the U.S. The Trump administration has largely demonstrated a range of attitudes from skepticism to antipathy regarding immigration, refugees, and asylum seekers. These attitudes are evident in everything from the travel ban against predominantly Muslim countries (including countries in significant conflict, such as Syria and Yemen); to the ongoing controversies surrounding the southern border with Mexico, where unprecedented numbers of mostly families from Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras are coming to seek asylum in the U.S. from the turmoil and violence in Central America’s Northern Triangle. The White House has also drastically scaled back the U.S. refugee resettlement program, which now brings in the smallest number of refugees in decades. The U.S. public, however, generally regards immigration as positive for the country, according to the Pew Research Center, though there are sharp differences based on political party affiliation and age.

The AACRAO Policy Paper and the Pledge for Education

As part of the Article 26 Backpack project team, AACRAO convened a Policy Working Group to shine a light on policies at the institutional level that might impede displaced students from gaining admission to a U.S. institution. The AACRAO Policy Working Group included representatives from U.S. universities, community colleges, and organizations that work to reduce such barriers. Small teams drafted sections of the paper over a period of months, capturing their various perspectives. The paper begins with a broad discussion on access to U.S. higher education, and then moves on to the issue of credential evaluation and recognition in the context of college admissions. It also focuses on barriers and providing guidance to those organizations seeking to employ best practices.

The first section represents the voice of the academy, professors and university scholars who have focused on refugees and other displaced migrants in their research or practice. This group argues that higher education has a responsibility to help fulfill Article 26 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and describes the barriers refugees encounter at both the public policy level and in universities and colleges in the U.S.

The second section provides the perspective of displaced scholars. It was written by representatives from the two leading organizations working to place displaced and threatened scholars in host universities in other countries, including the U.S.: IIE’s Scholar Rescue Fund (IIE-SRF) and the Scholars at Risk (SAR) Network. The section provides an overview of current threats to scholars worldwide, as well as some historical context for the resettlement of displaced academics in the U.S. beginning during the First World War and later with the Nazi takeover of Germany. It describes the important role that universities play in helping displaced scholars, including typical challenges and successes, as well as best practices.

Displaced students are the focus of the third section. Its authors represent several organizations that work directly with refugee and displaced students. After a brief overview of general challenges, this section showcases several case studies of individual displaced students studying in the U.S. For example, Warda, a Palestinian student from Syria, was admitted to Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA) with the help of the Syrian student-serving organization Jusoor, EducationUSA, IIE PEER, and SIPA.

The fourth section focuses on the perspectives of U.S. institutions that host displaced students and scholars. Written by admissions directors and international officers from several universities and colleges that enroll significant refugee student populations, it provides some general thoughts on admitting displaced students. It then follows with case studies from individual institutions, and focuses on particular refugee populations, such as the Lost Boys (and Girls) of Sudan.

The final section, the Toolkit, provides solid, practical recommendations on how to work toward admitting students who cannot access full official or verifiable documentation. The working group for this section consisted of representatives from WES along with colleagues from two other prominent U.S. credential evaluation organizations and AACRAO. To draft these recommendations, we built on our combined research, knowledge, and experience—including WES’ research into international best practices and its work through the WES Gateway Program and preceding pilot project for Syrian refugees in Canada. We also spoke with our colleagues in admissions at U.S. universities and colleges, as well as leaders from the Presidents’ Alliance on Higher Education and Immigration and the Community College Consortium for Immigrant Education (CCCIE).

The Toolkit begins with an overview of students’ challenges obtaining official documentation from conflict zones, or from countries in political turmoil or which have recently experienced a natural disaster. It then examines the importance of proactive institutional policy making in this area, to provide as many opportunities as possible for displaced students to gain admission. This subsection features a checklist of questions for individual institutions and offices to consider when rethinking policies and procedures.

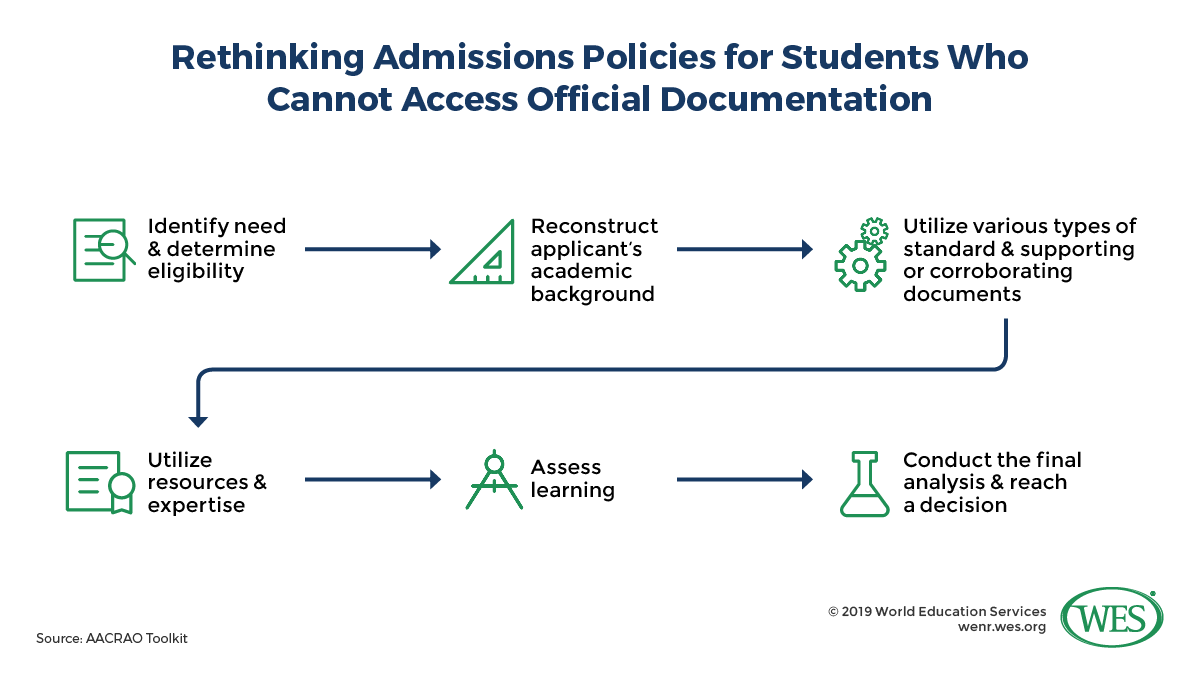

The recommendations then follow a general six-step process very similar to WES recommendations issued in its 2016 report. The steps (shown here verbatim) can be tailored to each institutional context:

Finally, the Toolkit provides tips for those institutions wishing to work with a credential evaluation service on this topic, whether for the first time or with a trusted partner. Its final thoughts are on broader barriers that displaced students confront in U.S. higher education. The Toolkit ends with a list of resources.

In releasing this paper, AACRAO has called on higher education institutions, government, and organizations that serve higher education to sign its Pledge to Support Vulnerable and Displaced Students, otherwise known as the Pledge for Education. The pledge calls for all to “recognize our responsibility and duty” to assist displaced students and scholars in integrating into and accessing higher education. WES has proudly signed the pledge.

Moving Forward

The world’s refugee crisis is unlikely to abate anytime soon, as war continues in countries like Syria, Yemen, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. New crises continue to erupt and unfold, as is the case in Venezuela. The U.S. will likely continue to be a top destination for the displaced, despite the political and social opposition from certain corners of U.S. society. Higher education will continue to play an important role in helping displaced individuals integrate into their new host societies and potentially help educate future leaders who will rebuild post-conflict and post-disaster societies.

The collaboration that AACRAO’s policy paper represents will be key to encouraging and assisting U.S. higher education institutions to find ways to help students surmount significant barriers. WES, for its part, has begun testing the WES Gateway Program in the U.S., working with partners in selected communities and academic institutions that request our assistance. The hope is that the higher education community across the U.S., as well as worldwide, will do its part in this crisis, and embrace talented students and scholars who find themselves in vulnerable, unstable situations.

1. For an overview of initiatives in Europe and North America, see Streitwieser, B., Loo, B., Ohorodnik, M., & Jeong, J. (2018). Access for refugees into higher education: a review of interventions in Europe and North America. Journal of Studies in International Education, online edition. Retrieved from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1028315318813201.