Education in Egypt

Ramage Y. Mohamed, Credential Analyst, WES, Makala Skinner, Research Associate, WES, and Stefan Trines, Research Editor, WENR

An Introduction to Modern Egypt: A Fast-growing Country with Mounting Socioeconomic Problems

In what is said to be one of the most ambitious construction projects in history, Egypt is currently building a new capital city that more than five million people will be able to call home. Envisioned as a “smart” 21st century city with “663 hospitals and clinics, 1,250 mosques and churches,” Africa’s tallest building, and an amusement park four times larger than Disneyland, the yet unnamed capital is being designed to help decongest Cairo, a desperately overcrowded metropolis which competes with Lagos for the title of Africa’s most populous city. Arable land and living space are scarce commodities in Egypt. The arid country consists almost entirely of desert—97 percent of the population live in the Nile Valley and Delta, which make up only 5 percent of Egypt’s territory.

But the new capital is also designed to serve as a showcase for Egyptian renewal—a symbol that the country is on the rise again after years of political turmoil and instability. Over the last eight years, Egypt witnessed the overthrow of the dictatorship of Hosni Mubarak in a popular revolution, followed by democratic elections that brought the Islamist Muslim Brotherhood to power. Unpopular with many Egyptians, that government was quickly ousted and replaced by yet another military-dominated regime, which has since been institutionalized in what most observers consider sham elections. The new capital is aptly nicknamed “Sisi City,” after Egypt’s current strongman president Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, a former general who championed the ambitious prestige project.

The Arab Republic of Egypt—the country’s official name—is the most populous country in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) with 98.2 million people, some 90 percent of whom are Sunni Muslims. World famous for its ancient civilization and sights like the pyramids, the country has historically been highly influential in the Arab world. After promoting Arab nationalism and socialism under President Gamal Abdel Nasser in the decades after World War II, Egypt subsequently aligned with the West, particularly the United States. Egypt’s control of the Suez Canal and its significance in the Arab-Israeli conflict make the country strategically important, so much so that Egypt continues to receive the second-largest amount of U.S. foreign aid after Israel.

While much of Egypt’s economy remains controlled by its powerful military, since the 1970s the country has transitioned from a socialist system to a free-market economy—a strategy that yielded strong economic growth, much to the delight of institutions like the World Bank. Economic growth rates during the Mubarak regime were so high that observers began to label the country an economic “tiger on the Nile.”

However, Egypt’s political turmoil of the early 2010s triggered an economic downturn as foreign investors fled the country and Egypt’s once thriving tourism industry collapsed. Egypt’s economy is now growing again, but economic expansion is largely non-inclusive and of limited benefit to the larger populace. Social stagnation, poverty, and high unemployment rates caused much of the widespread discontent behind the popular revolution of 2011, notably among educated urban youths.

Unemployment is particularly high among Egypt’s burgeoning youth population and its university graduates. In 2015, Egypt’s overall unemployment rate was 12.8 percent, while unemployment among 15- to 29-year-olds and university graduates stood at 30 percent and 34 percent, respectively. Poverty, meanwhile, has also risen in recent years: In 2015, almost 28 percent of Egypt’s population lived below the national poverty line amid one of the lowest income levels in the MENA region. Egypt’s GDP per capita—USD$2,412 in 2017—is less than half that of countries like Iraq or Iran, for example. As a result of these trends, Egypt continues to experience high levels of outmigration. More than nine million Egyptians currently live abroad, mostly in other MENA countries, but also in the U.S., Canada, Europe, and Australia.

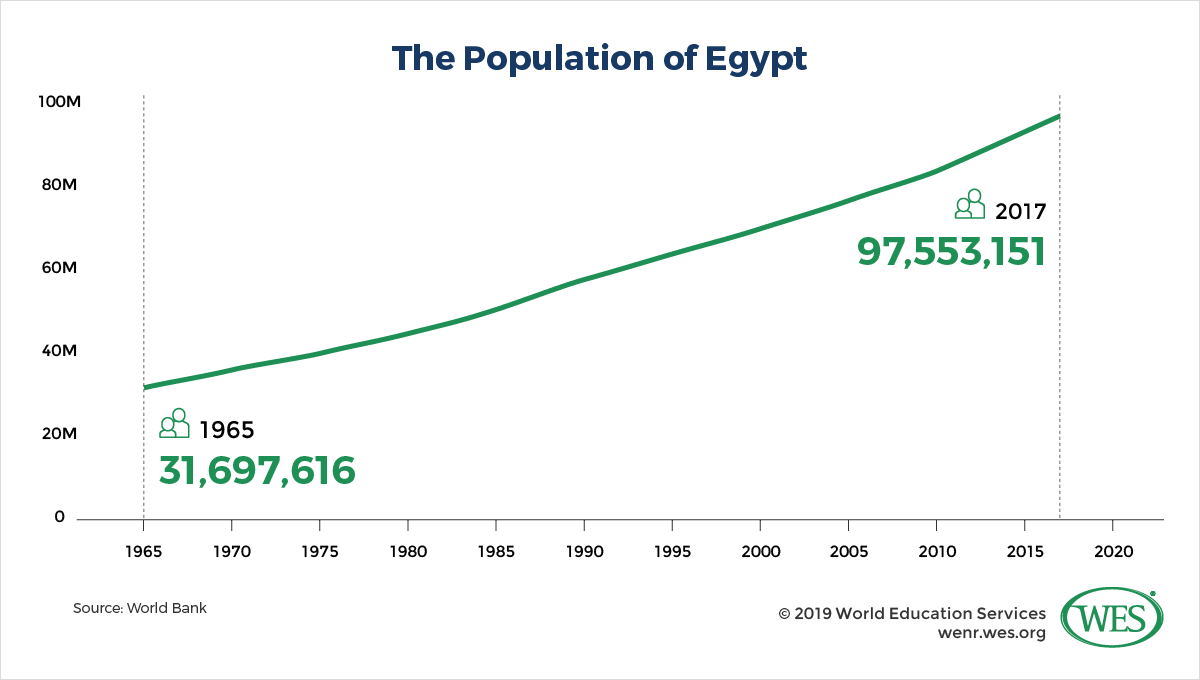

One of Egypt’s most pressing challenges is its skyrocketing and destabilizing population growth driven by high fertility rates. To put this growth into perspective, Egypt in 1960 was still a relatively small country of only 27 million people. Between 1983 and 2017 alone, Egypt’s population doubled—and the country is said to currently grow by another 1.6 million people annually. About 40 percent of Egyptians are under the age of 18. The population is expected to swell to some 153 million by 2050, according to UN projections. By most accounts, current economic growth rates are insufficient to provide adequate economic opportunities for this mushrooming population. Global warming could further exacerbate population pressures, since rising temperatures and sea levels threaten to deplete the country’s already scarce arable land and water resources.

Problems in the Education Sector

Egypt has made significant progress in a number of crucial areas in recent years—its official youth literacy rate, for instance, increased from 85 percent in 2005 to 94 percent in 2017, while the number of elementary-age out-of-school children has dropped by 50 percent over the past five years after skyrocketing during the revolution in 2011, per data from UNESCO Institute of Statistics (UIS).

But needless to say, Egypt’s population growth places enormous strains on the country’s education system. The total number of children enrolled in elementary school jumped from 9.5 million in 2005 to 12.2 million in 2017, and from 6.7 million in 2009 to 8.9 million in 2015 at the secondary level, resulting in greater funding requirements, capacity shortages, and overcrowded classrooms. The pupil-to-teacher ratio has slightly increased in both elementary and secondary education in recent years, while teacher salaries are falling. Parents have to spend more of their income on private tutoring and other education-related expenses. There’s also a substantial amount of “disguised illiteracy,” that is, some 30 percent of schoolchildren are estimated to “lack basic skills for reading and writing.” Most of them live in rural regions.

Egypt’s higher education system, meanwhile, is underfunded and inefficient by most accounts. In its Global Competitiveness Report 2017–2018, the World Economic Forum ranked the quality of Egypt’s education system 130th among 137 countries. The political turmoil and violence on university campuses in past years hasn’t helped either. In the 2013/14 academic year alone, Egypt’s public universities were paralyzed by more than 1,600 student protests, causing the government to deploy security forces on campuses. Twenty-one students were killed in violent clashes between 2013 and 2016; hundreds more were arrested or expelled. Academic freedom, university autonomy, and freedom of expression remain severely stifled.

Perhaps the biggest structural problem, however, is the Egyptian universities’ outdated curricula. The schools consequently churn out “graduates with no future,” who lack the necessary skills for employment in a modern economy. As of 2014, high school and university graduates reportedly took seven years on average to find gainful employment. Many graduates ended up working odd jobs in the informal sector, where most of Egypt’s working population is employed. In 2015 a group of students publicly burned their doctoral and master’s diplomas in protest of this situation.

Aware of how the youth employment crisis could lead to political instability, the Egyptian government is currently intensifying efforts to improve the country’s education system. President Sisi recently declared 2019 “the year of education,” and public education spending was increased by 8 percent for the 2018/19 fiscal year. That said, overall funding levels in Egypt are still relatively low compared with those of countries at similar levels of socioeconomic development and as a percentage of overall government spending. Egyptian education spending as a percentage of GDP in 2014/15 (4 percent) was lower than in 2004/05 (4.2 percent), and fell short of spending levels in Morocco or Tunisia, for example. Spending per tertiary student stood at USD$424 in 2012, compared with an average of USD$15,028 in OECD countries.

The government intends to further increase funding, boost tertiary enrollment rates, and implement a range of reform projects, including the construction of eight new technical universities, aided by a USD$500 million loan from the World Bank. The country’s Strategic Vision for Education to 2030, adopted in 2016, seeks to expand technical and vocational education and training (TVET) and distance education, develop curricula more aligned with labor market needs, and improve student-to-teacher ratios and quality assurance and accreditation mechanisms, as well as teacher training. However, despite positive developments in a number of important areas in recent years, it remains to be seen how successful Egypt will be in strengthening and reforming its education system amid surging population growth.

Inbound Student Mobility

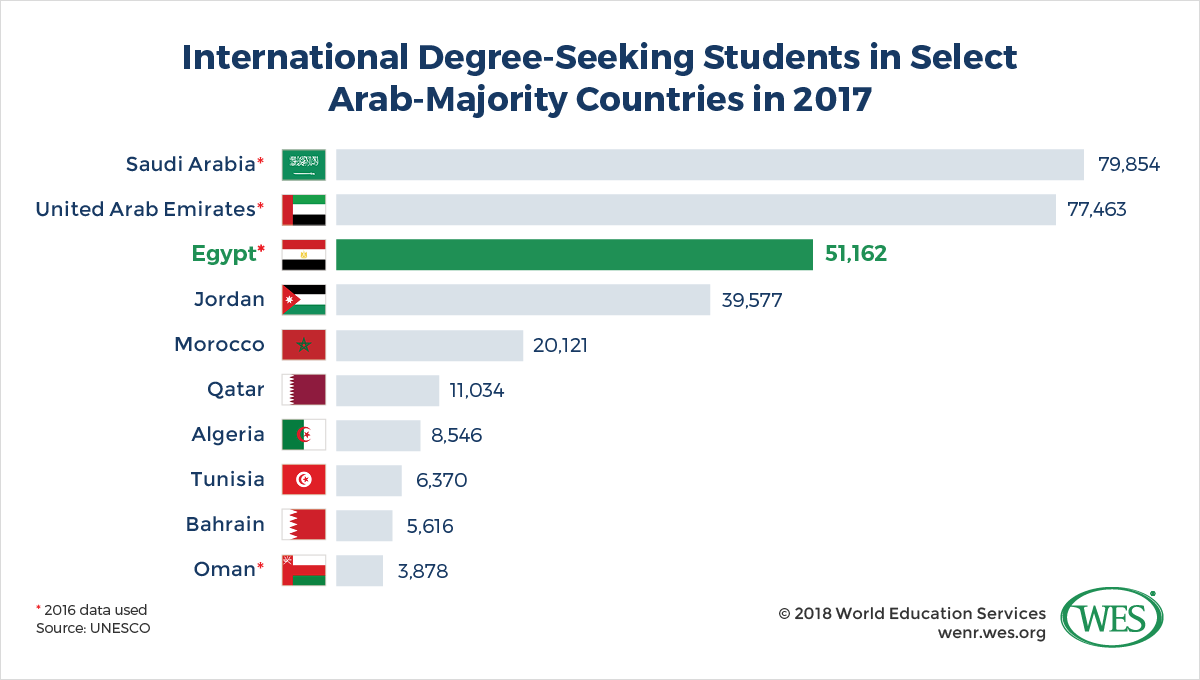

Perhaps surprisingly, given the political instability in recent years, Egypt has become an increasingly important and booming international education hub in the MENA region. Over the past decade and a half, the number of international degree-seeking students in the country has nearly doubled, jumping from 27,158 students in 2003, to 51,162 in 2016, according to UIS data. While political upheaval caused a dip in international enrollments between 2011 and 2013, Egypt’s inbound mobility steadily rebounded and appears to have fully recovered today.

This trend persists despite the country’s continued high profile terror attacks, and its categorization as a risky travel destination. Egypt falls into the “high warning” category of the Fund for Peace’s 2018 Fragile States Index, in which it is ranked 36 out of 178 countries (1 being the most fragile country and 178 being the most stable). Lingering political violence notwithstanding, Egypt is now the third-most popular destination country for international degree students within the Arab world, surpassed only by Saudi Arabia (79,854) and the United Arab Emirates (77,463).

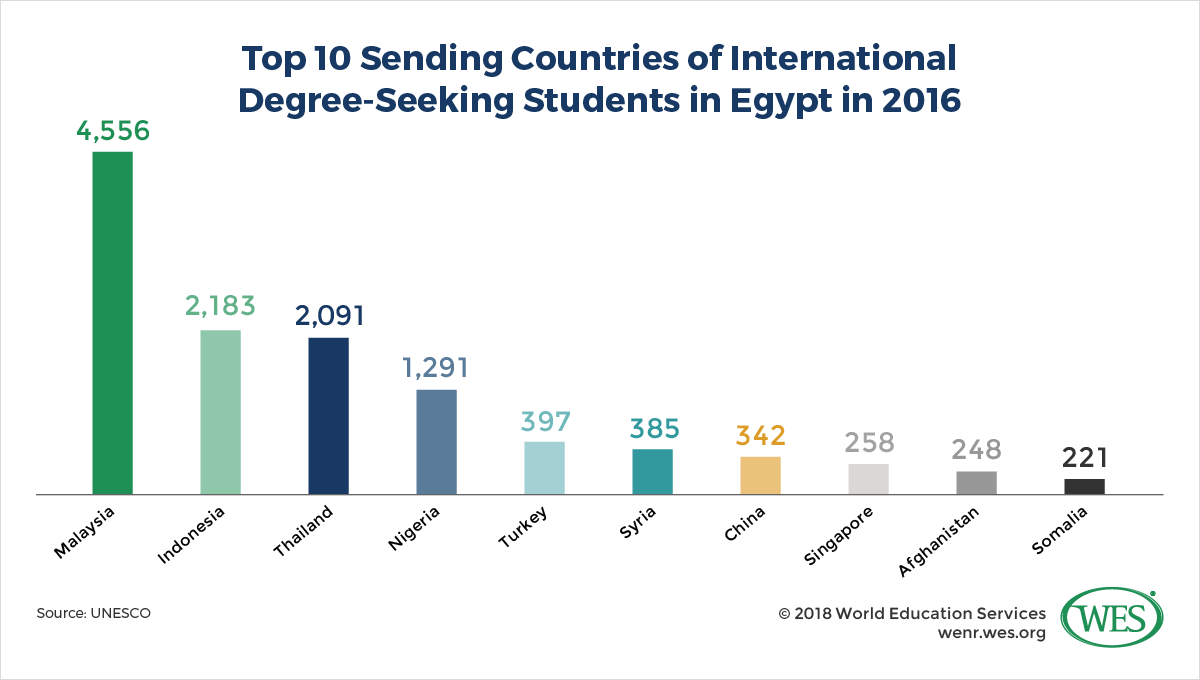

The international student body in Egypt is diverse. Most come from Southeast Asia, but Egypt is also a major destination for students from other Arab countries, as well as sub-Saharan African countries like Nigeria. More than 70 percent of foreign students in Egypt are male, and the vast majority study at public universities.

Malaysia sends more than twice the number of students as the second-most sending country, Indonesia. But while Malaysia sent the most—4,556 students in 2016—it accounts for only 9 percent of all inbound students. Clearly Egypt attracts students from a wide variety of countries rather than drawing from only a few.

Factors that make Egypt attractive for foreign students are its relatively low tuition and living expenses compared with those of other Arab countries. While tuition fees at private universities and international secondary schools can be high, fees at public universities are usually modest. Tuition at public universities like Ain Shams University or Alexandria University, for example, is only USD$1,000 for non-Egyptian students per year. International students spend on average between USD$7,000 and USD$14,000 to complete a degree program in Egypt, whereas students in Dubai, United Arab Emirates (UAE), pay anywhere between USD$10,000 and USD$19,000 for an undergraduate degree. In conjunction with their low tuition, Egyptian public higher education institutions (HEIs) freely admit non-citizens, while some Arab countries do not.

International partnerships and the availability of scholarships also facilitate student inflows. Egypt and Malaysia, for example, have a strong relationship within the higher education sphere. This includes the Education Malaysia Egypt office, created in 1960, which provides services to Malaysian students who are pursuing tertiary education in Egypt. In 2016, Malaysian authorities set up the Malaysian Students Education Fund, which provides financial “assistance to Malaysians studying in Egypt”—despite the fact that education costs are already lower in Egypt than in Malaysia, where domestic students spend approximately 67,600 Malaysian Ringgit (USD$16,212) on average on tuition, accommodations, and living expenses.

Egypt’s standing as an international study destination is enhanced by the relatively strong showing of its universities in international rankings. While the top-ranked institutions in the Arab world are located in countries like Saudi Arabia or the UAE, nine Egyptian universities were included in the top 31 of the 2018 Times Higher Education ranking of universities in the Arab world, compared with five Saudi universities and four Emirati. Egyptian universities represent 13 of the top 100 institutions according to the 2018 QS World University Rankings for the Arab region. Egypt is tied with Jordan for the country with the second-most schools in the top 100, coming in only behind Saudi Arabia, which has 21 schools on the list.

Foreign Branch Campuses: A Driver of Future Student Inflows?

Furthermore, Egypt hosts several reputable foreign universities, including the American University of Cairo, the German University in Cairo, the British University in Egypt, and the Université Française d’Egypte. While most of these private universities were established a long time ago, the government is attempting to turn Egypt into a transnational education hub and attract more foreign branch campuses, notably in “New Cairo,” Egypt’s new administrative capital now under construction.

In July 2018, Egypt enacted new legislation that regulates foreign branch campuses, while also luring foreign providers with streamlined licensing procedures, inexpensive real estate, and tax exemptions. Foreign branch campuses must be approved by the Egyptian government. They are also required to teach the same programs as on their main campuses and to award degrees that are recognized in their home countries. Otherwise, foreign providers are promised wide-ranging institutional autonomy and academic freedoms, at least on paper.

The government hopes that foreign branch campuses will enhance the global competitiveness of Egypt’s education system, expand capacity, and improve the performance of domestic universities by increasing competition. Beyond that, it expects transnational education to foster more research collaboration and help propel inbound student mobility, which still has ample room for growth.

At present, Egypt has a relatively low inbound mobility ratio of only 2 percent, a figure that is dwarfed by much higher inbound mobility ratios in Persian Gulf monarchies like the UAE and Qatar, which in 2016 had mobility ratios of 49 percent and 38 percent, respectively (UIS). The Egyptian government intends to increase the number of international students to 6 percent of the tertiary student population by 2030, and turn Egypt into an international education hub of global scale.

Lately, Egypt’s efforts to attract more foreign branch campuses are paying off. In November 2017, Egypt’s Minister of Education announced that six new international universities from Canada, France, Hungary, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the U.S. will be built in Egypt’s new administrative capital. A memorandum of understanding with the U.K. followed in early 2018 to establish more British branch campuses in Egypt—already the fifth-largest host country for U.K. transnational education, with nearly 20,000 students pursuing British degrees in joint degree programs, according to PIE News.

Likewise, a number of Canadian universities, including the University of Prince Edward Island, Cape Breton University, and the Memorial University of Newfoundland, have partnered to establish branch campuses in the framework of the University of Canada, Egypt consortium. A branch campus by the Swiss University of Lausanne is currently under consideration as well.

On the other hand, the University of Liverpool recently tabled plans to build a campus in Egypt because of concerns over “reputational damage.” British and Canadian universities have been heavily criticized for cooperating with the Egyptian government despite its flagrant human rights violations. In an open letter published in the Guardian, more than 200 British academics in 2018 accused U.K. institutions of colluding “in masking human rights abuses.” The academics questioned “… the wisdom and legitimacy … to do business as usual with an authoritarian regime that systematically attacks research, education and academic freedom.”

Outbound Student Mobility

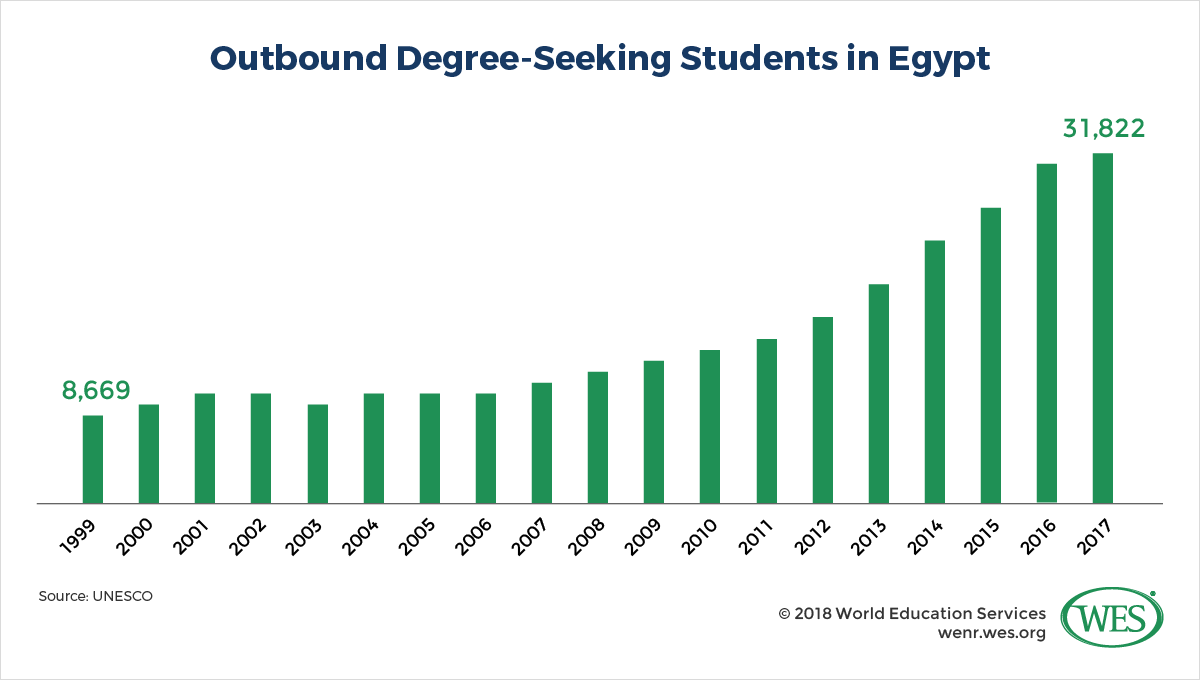

Though outbound student mobility in Egypt is more modest compared with inbound student flows, outbound numbers have nevertheless grown rapidly in the last decade. Since 2008, the number of Egyptian degree-seeking students pursuing their education abroad has nearly tripled, from 12,331 to 31,822 students in 2017, according to the UIS. Year-over-year growth rates reached their peak in 2013, most likely driven by political turmoil. In terms of total numbers, Egypt is now the fourth-largest sending country of international students in the Arab world after Saudi Arabia, Morocco, and Syria.

There is little question that the political instability and dysfunction of parts of the Egyptian education system in recent years has contributed to an increase in outbound student flows. Eighty percent of Egyptian students polled by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in 2013, for instance, expressed interest in emigrating amid high unemployment and “deteriorating and non-democratic” state institutions.

However, Egypt has tremendous long-term potential for further growth in outbound student mobility going beyond immediate political factors. The country’s rapid youth population growth means that demand for education will surge and likely continue to outstrip supply. Egypt’s tertiary gross enrollment ratio has remained largely stagnant over the past two decades, although it recently increased from 31 percent in 2014 to 34.5 percent in 2016 (for comparison, the gross enrollment ratio stood at 30 percent in 1999). While the establishment of more international branch campuses in Egypt may help absorb some of the demand, other students will likely head abroad for better education and employment opportunities.

That said, the percentage of Egyptians studying abroad is still small—the country’s outbound mobility rate stood at only 1.1 percent in 2016, perhaps the lowest in the Arab region, dwarfed by outbound ratios of 7.8 percent in Jordan and 22 percent in Qatar, per the UIS. This is likely due to the lack of disposable income among the Egyptian population for an expensive overseas education. Egypt’s middle class, already small, has been decreasing in recent years. According to the World Bank, Egypt’s middle income population—people living on USD$4.9 per day in 2005 U.S. dollars—“shrank from 14.3 percent in the mid-2000s to 9.8 percent by the end of the decade.” Incomes and living standards continue to be strained by austerity measures imposed by the International Monetary Fund and high inflation rates today.

Adding to these economic constraints, declining exchange rates of the Egyptian pound against the U.S. dollar over the past decade have made studying abroad more expensive for Egyptians. Given these financial realities, international education largely remains the province of wealthy elites and those that can obtain scholarships. Government funding for study abroad scholarships in Egypt is currently low, so that scholarship funding needs to be sourced primarily externally. While Egypt is generally considered a dynamic outbound market, the scope of future mobility from Egypt depends on whether the country can achieve more inclusive and equitable economic growth, at least to some extent.

Destination Countries

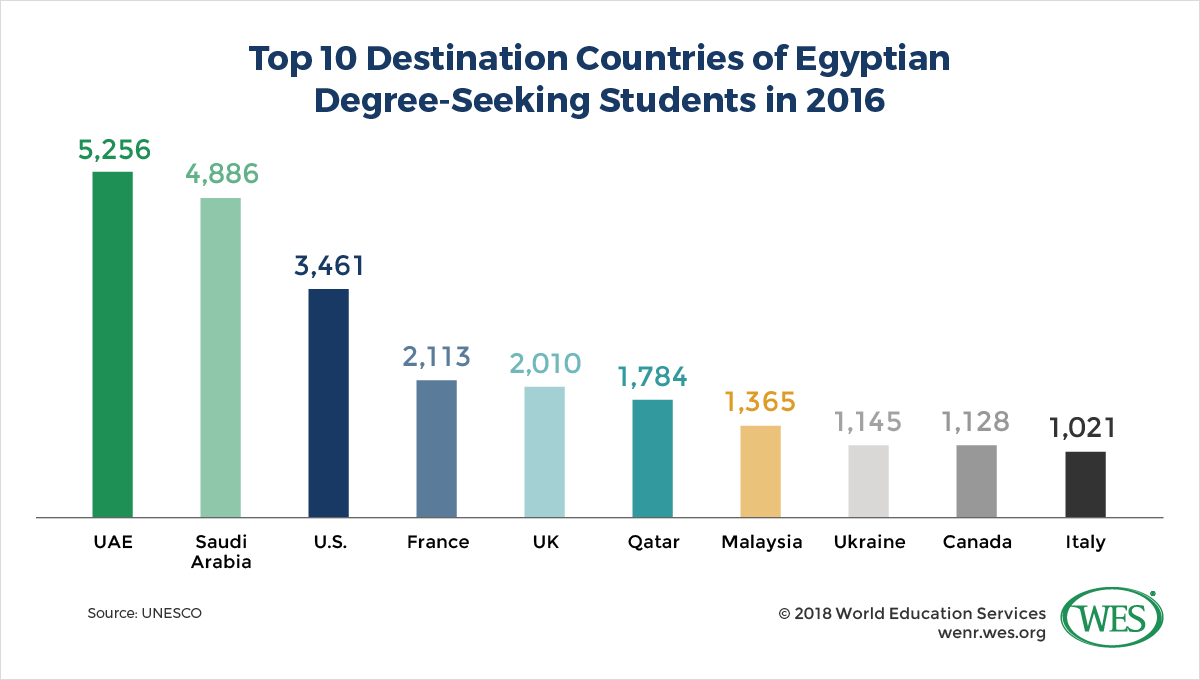

Degree-seeking Egyptian students pursue their studies in a variety of countries, although about one-third of them study in the UAE and Saudi Arabia, the top two destination countries, trailed by the U.S. by a significant margin. Linguistic, cultural, and political ties likely play a role in making the UAE and Saudi Arabia the top destinations, as do academic cooperation and labor migration patterns, coupled with the presence of high-quality universities in the Persian Gulf region.

According to the British Council, Egypt at the beginning of the decade “was involved in around one-third of Saudi Arabia’s joint research articles, and vice versa.” Both the UAE and Saudi Arabia are simultaneously major destinations of Egyptian labor migrants, with Saudi Arabia alone hosting more than 2.9 million Egyptian workers in 2016.

France and the U.K. are the fourth and fifth most popular study destinations, followed by Malaysia. Aside from the thriving educational exchange with both the U.K. and Malaysia, student flows to European countries are likely stimulated by access to scholarship funding. More than 1,000 Egyptian students have benefited from European Erasmus scholarships as of 2017, in addition to other funding opportunities. Students from the public Alexandria University and Cairo University have been the main recipients. France maintains close diplomatic relations with Egypt, including academic exchange, and in 2017 announced that it would increase the number of scholarships available to Egyptian students and researchers.

Trends in the U.S. and Canada

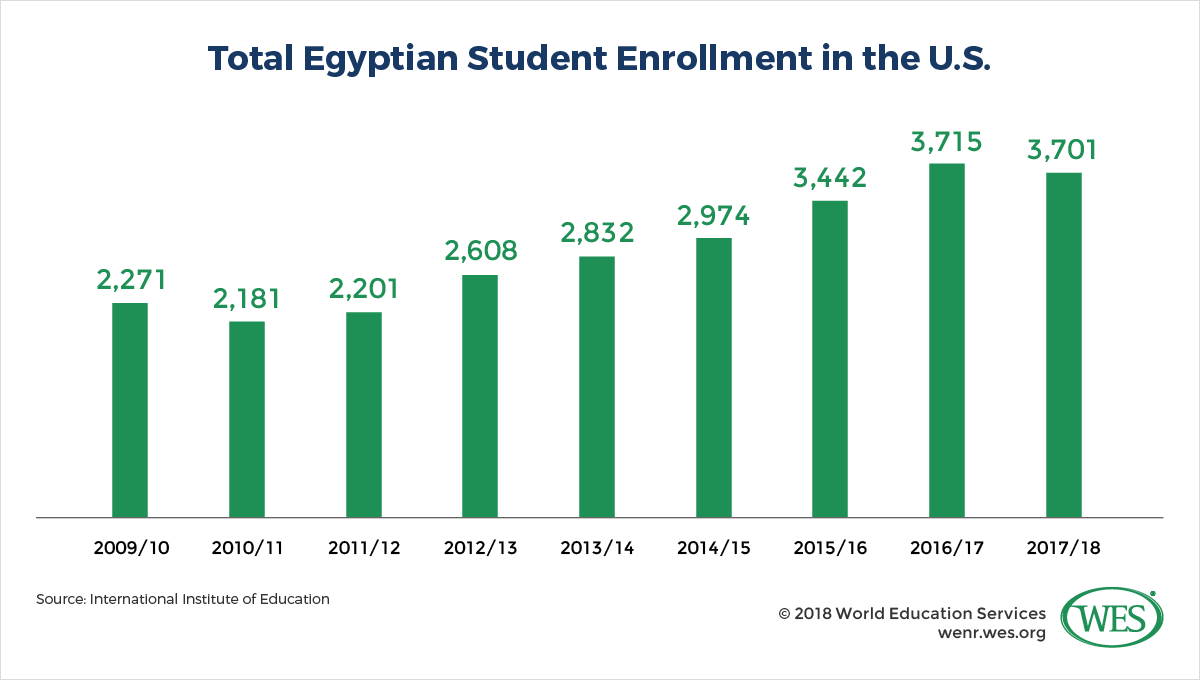

Home to a relatively small but wealthy Egyptian diaspora, the U.S. has traditionally been a popular destination for Egyptian students. However, after increasing pointedly over the past decade, enrollments by Egyptian students are currently stalling, despite the availability of scholarship opportunities for public university students. According to the Institute of International Education’s Open Doors data, the 2017/18 academic year marked the first time since a slight downturn in 2010/11 that Egypt sent fewer students to the U.S. than the year before. The Trump administration’s travel ban—which restricts entry for those from seven countries, five of which are majority Muslim and located in the MENA region—in conjunction with stricter visa procedures, may dissuade Egyptian students and account for this stagnation, although this is speculative.

Of the 3,701 Egyptian students in the U.S. in 2017/18, nearly half pursued undergraduate degrees (41 percent) and graduate degrees (43 percent); 12 percent were on Optional Practical Training; while only 4 percent were enrolled in non-degree programs.

Just as Egyptian student mobility to the U.S. is stagnating, it is rising sharply in Canada, growing by 21 percent between 2016 and 2017 alone. This increase coincides with a rapid upsurge of international student inflows to Canada in general, due to welcoming student visa and immigration policies, including easy access to post-study work opportunities and residency pathways for students. While the total number of international students in Canada has grown by 142 percent between 2009 and 2017, the number of Egyptian students increased by 112 percent, from 1,040 to 2,210 students, according to government data. This number is more than seven times what it was in 2000, when only 310 Egyptian students pursued their education in Canada—now the ninth-most popular destination for Egyptian degree-seeking students, per the UIS.1

In Brief: Egypt’s Education System

Egypt has an ancient tradition of religiously based education and was formerly an intellectual center of the world. The country is said to have the world’s oldest university still in operation, the Al-Azhar University in Cairo, founded circa AD 9712 and still considered one of the most prestigious Islamic universities worldwide. Secular education was introduced in the 19th century when Ottoman rulers created an elitist “dual education system” in which the general population continued to be educated in traditional Islamic schools (kuttabs), while civil servants were educated in secular government-funded schools (madrasas).

After Egypt came under British control in 1882, education was deprioritized. The British were primarily interested in educating civil servants in English-medium schools and neglected the education of the masses. The colonial administration decreased spending on education and charged tuition fees for elementary schools. Higher education was expensive and largely the province of affluent elites.

It was not before 1949 that free and universal elementary education was introduced in Egypt. This was followed by a state-driven expansion of the education system under the socialist government of President Nasser (in office from 1954 to 1970). Higher education was made tuition free and admission was ensured for all high school graduates. University graduates were even guaranteed employment in the public sector—an attempt to make the system less elitist and prevent social unrest among educated youths.

These policies resulted in a significant growth of the system. The number of universities increased from five in 19523 to 12 in 1976, while the number of tertiary students more than doubled—from 233,300 to 480,000 between 1971 and 1976 alone. However, given Egypt’s population growth, the governmental employment guarantee became exceedingly untenable while the increasing massification of higher education led to a deterioration of quality standards. The employment guarantee was eventually tabled in the early 1990s under President Mubarak. Tuition-free public higher education and admissions guarantees across the board were also abolished.

Today, Egypt has the largest education system in the MENA region with 12.2 million elementary students, 8.9 million secondary students and 2.8 million tertiary students, according to UIS data. In response to the surging demand for higher education, Egypt in the early 1990s began to liberalize its state-controlled system and allowed the establishment of private HEIs (in addition to the already existing private American University in Cairo). Between 1996 and 2006 alone, the number of private universities increased from 1 to 16. However, total enrollments in private institutions remain relatively small compared with those of other African countries that pursue privatization to accommodate surging demand. Only 20.6 percent of tertiary students were enrolled in the private sector as of 2016.

Administration of the Education System

Egypt is administratively divided into 27 governorates, the largest of which are Cairo and Giza on the West Bank of the Nile. Governorates are further divided into hundreds of municipalities and smaller sub-municipal village districts. Egypt has a centralized system of government—although some officials are elected at the local level, and there have been attempts toward greater decentralization in policy areas like education in recent years. The governors of the different administrative regions are directly appointed by the president, and local governments are funded by the central government. In education, overall policies are set at the national level and implemented by local education directorates in the individual governorates.

Education is overseen by a number of central government bodies, including the Ministry of Education (MOE) and the Ministry of Higher Education. The MOE supervises preschool and elementary and secondary education. Steered by the High Council of Pre-University Education, it is responsible for national examinations, curricula, the development and provision of textbooks, teaching materials, and other matters.

Higher education at both public and private institutions is overseen by the Ministry of Higher Education, which supervises the Supreme Council of Public Universities, the Supreme Council of Higher Institutes, and the Supreme Council of Private Universities—bodies which coordinate policies between institutions, provide quality control, and approve new HEIs and programs. Chaired by the Minister of Higher Education, these councils are made up of the presidents of all institutions within their respective sectors. In addition, there’s a National Authority for Quality Assurance and Accreditation in Education (NAQAAE), an autonomous body under the prime minister that accredits academic institutions and programs.

Public HEIs are funded by the Ministry of Finance, which typically provides from 85 to 90 percent of operating expenses. Modest tuition fees set by the government, along with donations, consulting fees, and so on, raise the remainder of public institutions’ revenues. Some universities are authorized to charge higher tuition fees of between USD$455 and USD$1,139 (2017) for newly created special programs. Private institutions don’t receive government funding and are mostly funded by tuition fees, the permissible range of which is determined by the Supreme Council of Private Universities.

Religious education is overseen by the Ministry of Religious Affairs, but Al-Azhar University and its vast network of affiliated schools and colleges are a special case. The institution is administered by the Al-Azhar Supreme Council, which has a substantial degree of autonomy and influence. Al-Azhar does not only run post-secondary Islamic research institutions, but also thousands of elementary and secondary schools nationwide, most of which teach a secular curriculum combined with religious education. Graduation from one of these schools and passing a special “Al-Azhar secondary school” examination is required for admission into Al-Azhar University.

Overall, Al-Azhar-affiliated schools enroll about two million students. Originally founded as a private institution, it “is now a state entity that has evolved into a behemoth running large and dispersed parts of the religious and educational apparatus of the country.” Given the strong influence of Islam in Egypt and its importance to Islamist opposition movements like the Muslim Brotherhood, political control over Al-Azhar has been a contested issue for decades.

TVET is overseen by a multitude of institutions, resulting in this sector not being very integrated. The MOE and Ministry of Higher Education supervise TVET in upper-secondary schools and technical colleges, respectively, while other ministries, such as the Ministry of Trade and Industry or the Ministry of Manpower and Immigration oversee informal, industry-integrated TVET programs at vocational training centers.

Language of Instruction and Academic Calendar

The language of instruction is generally Arabic in both the school system and in higher education, but some public school curricula and subjects, as well as a number of university programs in professional disciplines, are taught in English. Several private schools and universities provide education in English, French, or German. The academic year in Egypt usually runs from late September to the end of May or early June at both schools and universities, although it may vary somewhat at private institutions. It is typically divided into two semesters (September to January and February to May or June).

Basic Education

Egypt’s constitution stipulates free and compulsory education for all children between the ages of 6 and 15, although there are plans to eventually extend compulsory education to secondary education (12 years of schooling). This corresponds to a “basic education” phase that lasts from grades one to nine, divided into six years of elementary education and three years of “preparatory” education. Children are entitled to two years of free kindergarten education prior to elementary education, but only about a quarter of children attended preschool education as of 2017. There are no formal admissions requirements at public schools at the elementary education stage. Even though education at public schools is technically free, these schools nevertheless charge small fees.

The elementary curriculum is set by the government for both public and private schools (except international schools) and includes general subjects like Arabic, mathematics, and science. English is taught from grade one, and religious education is mandatory at all stages of schooling. Recent reforms abolished year-end examinations during the first four years, but examinations are introduced in grade five and there is a final elementary school examination (qabul) at the end of grade six—students must pass this exam to be awarded the “primary certificate” and progress into preparatory school. Current reforms seek to de-emphasize the importance of the final examination in favor of school grades.

The net enrollment rate in elementary education has increased from 90 percent in 2005 to 97 percent in 2016, per UIS data. Children who dropped out of school and are above elementary school age have the chance to attend one-year programs at “second chance” community schools to obtain an elementary graduation certificate.

The subjects taught during the preparatory phase (grades seven to nine) include Arabic, agriculture, art, English, mathematics, music, religious studies, and social studies. After succeeding in final graduation examinations at the end of grade nine, pupils at secular schools receive the Basic Education Certificate, while pupils at Al-Azhar-affiliated schools receive the Al-Azhar Basic Education Certificate. The curriculum for Al-Azhar schools is generally the same as in secular public schools, but it places a greater emphasis on Islamic studies.

The final preparatory education examination (Adaadiya Amma) is a high-stakes external test. How well students perform determines whether they progress into the general secondary education track (in the case of high scores) or the vocational track (in the case of lower scores). Pupils who do not pass the exam after the second attempt are not allowed to enroll in upper-secondary education. However, they may also transfer into preparatory vocational schools in order to earn a certificate of “completion of basic education and vocational preparation,” which offers access to upper-secondary technical education.

At present, there are two types of public schools: Arabic schools and experimental schools. Arabic schools teach the national curriculum in Arabic, whereas experimental schools use English as the language of instruction and teach a second foreign language at the preparatory level (usually French or German). However, the MOE has announced that experimental schools will be phased out beginning this year. Instead, mathematics and sciences will now be taught in English at all public schools from the seventh grade on, at which point a second foreign language will also be introduced.

The MOE also plans to create a number of fee-based public international schools that teach curricula like the International Baccalaureate, as well as almost 100 Japanese schools that incorporate aspects of the Japanese school curriculum in addition to the national Egyptian curriculum. According to the ministry, there are presently 750 experimental schools compared with 49,000 general public schools. At the elementary level, there were 3,439 public Al-Azhar schools in 2013.

In addition, there are 7,000 private schools, which include religious schools, private language schools that teach the state curriculum in English, and some 100 international schools that teach foreign curricula (mainly British, U.S., German, and French). Given the funding problems in the public school system, private institutions can be of better quality and are becoming increasingly popular. However, the overall percentage of students attending private schools is still small. The share of enrollments at private institutions increased from 8 percent to 9 percent at the elementary level, and from 4.5 percent to 6.6 percent at the preparatory level, between 2004 and 2017 (UIS).

Private schools are expensive and therefore mostly attended by children from affluent households—35 percent of children from the highest wealth quintile attended private schools in 2007. While tuition at Egyptian private schools may be less than 1,000 Egyptian pounds (USD$112), the most expensive international school in Egypt, the Cairo American College (which despite its name is a K-12 school), charges exorbitant fees of USD$24,000 in the student’s final year. The strong depreciation of the Egyptian pound in recent years has led to skyrocketing tuition rates, increasingly pricing middle-class households out of the private sector despite governmental limits on fee increases.

Overall, the Egyptian system is characterized by distinct disparities in enrollment and graduation ratios between urban and rural regions, as well as between affluent and low-income households. According to one recent study, youths from the “highest wealth quintile and who live in … urban governorates … [have] a 98.5 percent chance of accessing higher education as compared to a 5.5 percent chance” among those who are “from the lowest wealth quintile and live in rural Upper Egypt.”

Upper-Secondary Education

About two-thirds of preparatory school graduates go on to upper-secondary education, which lasts three years (grades 10 to 12) and is not mandatory. The number of Egyptians enrolled in upper-secondary education has mushroomed by an enormous 65 percent over the last decade. This trend is driven by population growth as well as by increasing participation rates: The net enrollment ratio at this stage of education grew from 62.5 percent in 2014 to 67.5 percent in 2017.

Depending on their grades in the preparatory graduation examination, students can enroll in a general secondary (university-preparatory) or a technical secondary stream. In 2013, 55 percent of students enrolled in the technical stream, while 45 percent studied in the general secondary track. The latter percentage includes students at Al-Azhar schools, which teach a general secondary curriculum that emphasizes Islamic studies. Less than 9 percent of upper-secondary students were enrolled in private institutions in 2017.

General Secondary Education

At present, there are two different streams in the general secondary track: literary and science. All students in both streams study Arabic, English, religion, and citizenship education, but specialize in history, philosophy, psychology, and sociology in the literary stream, while students in the science track take subjects like biology, chemistry, mathematics, and physics. In addition, students choose from a range of electives, such as additional foreign languages, social studies, or music. However, the system is currently in flux—the MOE is rolling out a more integrated general secondary school curriculum that will collapse the two separate streams into one. There are also a small number of USAID-funded STEM schools set up to pioneer a more interdisciplinary STEM-focused curriculum.

Upper-secondary education concludes with a highly difficult final examination (Thanaweya Amma) at the end of grade 12. Performance on this standardized test in core subjects and electives is the main criterion for admission into public higher education in Egypt. Students who pass are awarded the General Secondary Education Certificate. Until recently, the exam was an external nationwide exam, but starting this year it will be administered in schools. In 2018, about 646,000 students sat for the exams.

Given the difficulty and importance of the high-stakes test, growing numbers of Egyptian students are relying on private tutoring to prepare for it. Annual fees for private test prep schools can be as high as USD$1,677 for grade 12. They have become an increasing financial burden on families, so much so that the MOE has started to close down some of these schools and is considering banning private tutoring altogether.

Another problem is examinations fraud. The leaking of exam questions, for instance, has become so prevalent that the government resorted to deploying electronic scanners to search candidates for cell phones and now penalizes exam leaking with up to one year of jail time. In 2015, it was reported that the government transported exam questions in military helicopters under guard of the Egyptian army.

To decrease the importance of final exams, which are now taken online, the MOE is also implementing a new testing system that will feature 12 exams dispersed over the entire three-year upper-secondary cycle (four each year), with the final GPA calculated on the basis of the four highest scored exams. To switch assessment from rote memorization to analytical skills, test takers are now allowed to bring textbooks and tablets into test centers. Tablets are expected to be given to all students free of charge in an attempt to increase students’ exposure to technology.

Technical Secondary Education

Technical education is provided in three- and five-year programs after preparatory education. Three-year programs are offered in three main specializations: industrial, commercial, and agricultural. Industrial programs are the most popular and agricultural programs, the least. The curriculum consists of general education subjects (usually around 50 percent), vocational subjects (40 percent), and electives (10 percent). Programs conclude with a final examination after which students receive the Technical Secondary Education Certificate in Industry/Commerce/Agriculture (diblômal-madâris al-thânawiyya l-fanniyya al-sinâ`iyya / al-tidjâriyya /al-zirâ`iyya). The certificate provides access to post-secondary programs at related technical institutes (see below), and university programs, as long as students score high enough on the final exams.

Five-year programs lead to the Advanced Technical Diploma. While these programs are also grouped into industrial, commercial, and agricultural streams, they provide vocational education at a higher level and usually include more concrete subject specializations, such as electronics engineering or tourism management, for example. Like the Technical Secondary Certificate, this credential provides access to higher education.

In addition to formal secondary TVET programs, there are informal training programs, such as apprenticeship programs and dual programs that combine theoretical instruction at vocational training centers with practical training. These programs are typically designed for employment and do not provide access to higher education. There is not much data available on this sector, but the UN and others have estimated that as of 2010 there were between 800 and 1,200 vocational training centers run by government institutions with some 480,000 trainees.

While the percentage of students in technical secondary education has decreased significantly in recent years since a higher share of students opt for the university-preparatory track, the overall number of TVET students has surged. More than half of Egyptian secondary students still attend vocational schools despite vocational education being “associated with academic failure, rather than being an alternative path to … decent work. It is perceived as a … last resort for academically low-performing students who are denied access to the general education.”

In addition, many of the roughly 600,000 students that graduate from secondary vocational school each year face poor employment prospects due to graduates being ill equipped for current labor market demands. The MOE is seeking to address this problem by shifting student evaluations from testing theoretical knowledge to assessing practical skills. According to current proposals, practical competency assessment will make up to 70 percent of the final graduation exams in the future.

Higher Education

Types of Higher Education Institutions

As of 2018, Egypt had 31 private universities and 26 public universities, including Al-Azhar University, in addition to a number of other government HEIs, such as the military academies or the Egyptian Police Academy. Whereas most public universities are large multi-faculty research institutions, many of them with branch campuses across the country, private institutions tend to be much smaller. Most of them are for-profit institutions enrolling fewer than 10,000 students. Only 20.6 percent of Egypt’s 2.8 million tertiary students were enrolled in private institutions in 2016, according to the UIS. Many private universities are located in Cairo and offer only undergraduate programs. The public Alexandria University is the largest Egyptian university with 183,500 students in 2017.

In addition to universities, there are hundreds of public and private technical colleges, and institutions called middle institutes and higher institutes, which typically offer two- or three-year diploma and four-year bachelor’s programs in more vocationally or professionally oriented disciplines. The number of private higher institutes has grown steadily over the past decades, from 40 in the mid-1990s to 141 in 2017.

Quality Assurance and Accreditation

While public HEIs have a certain degree of academic autonomy, the Ministry of Higher Education and the Supreme Council of Public Universities regulate matters like the structure of degree programs, admissions requirements, and enrollment quotas. Private institutions have greater freedoms, but they need government approval to operate and must comply with the regulations of the Supreme Council of Private Universities—a body headed by the Ministry of Higher Education. Government oversight is also ensured by the fact that “a representative of the Ministry of Higher Education has to sit on the board of each new private university in order to report back on the university’s activities.”

Over the past two decades, the Egyptian government has undertaken various efforts to raise quality standards at HEIs. Notably, it has pushed for the establishment of internal quality assurance centers at university faculties, and in 2007 created the National Authority for Quality Assurance and Accreditation of Education (NAQAAE). NAQAAE accredits universities as a whole, as well as individual faculties and programs. In order for universities to be granted full institutional accreditation, at least 60 percent of their faculties must be accredited.

The accreditation process involves two phases: An optional “pre-accreditation” period during which NAQAAE performs a “gap analysis” and produces an improvement plan, followed by a formal nine-month evaluation that includes an institutional self-assessment and further inspections by NAQAAE auditors. NAQAAE’s quality criteria are laid out in several guidebooks; they include adequate financial resources, management structures, teaching staff, facilities, research output, and quality assurance mechanisms. Accreditation is granted for periods of five years during which institutions must continue to submit annual self-assessments. Institutions that fall short on just a few criteria may be placed on “postponed accreditation” status pending improvements, while underperforming institutions may have their accreditation revoked.

Although accreditation is technically mandatory for all HEIs, the implementation of Egypt’s new quality control regime is still in transition and progressing sluggishly. In 2012, the American University in Cairo was the only university that received full institutional accreditation, while only 16 public university faculties did. By 2018, the latter number had risen to 181 public university faculties, 18 Al-Azhar faculties, and 66 faculties affiliated with private institutions. However, that represents only 19 percent of all faculties. NAQAAE maintains an online directory of accredited faculties and programs.

University Admissions

University admissions at public institutions is based on the General Secondary Certificate Examination. The process is centralized with the Ministry of Higher Education setting admissions quotas for universities and assigning students to programs based on their exam scores (or final GPA under the new system currently being implemented). Cutoff scores for specific programs are set annually and vary widely by institution and program. In 2014, the minimum average score for graduates in the science stream ranged from 205 to 404 out of a possible 410. Higher institutes have lower score grade cutoffs than universities. Grade requirements are particularly stringent for medical programs.

There are no additional entrance examinations or other admissions criteria at public universities, except in the case of a few select programs. Holders of the Technical Secondary Certificate may also enter university programs, but only if they have very high exam scores. While almost 100 percent of general secondary graduates go on to higher education, merely 13.5 percent of technical graduates do.

Private universities are free to set their own admissions requirements, even though the Supreme Council of Private Universities sets an overall minimum grade threshold. Concrete admissions requirements at private institutions vary, but they are often less competitive than at public universities, so that private institutions tend to absorb those students that could not get admitted into public HEIs.

The Higher Education Degree Structure

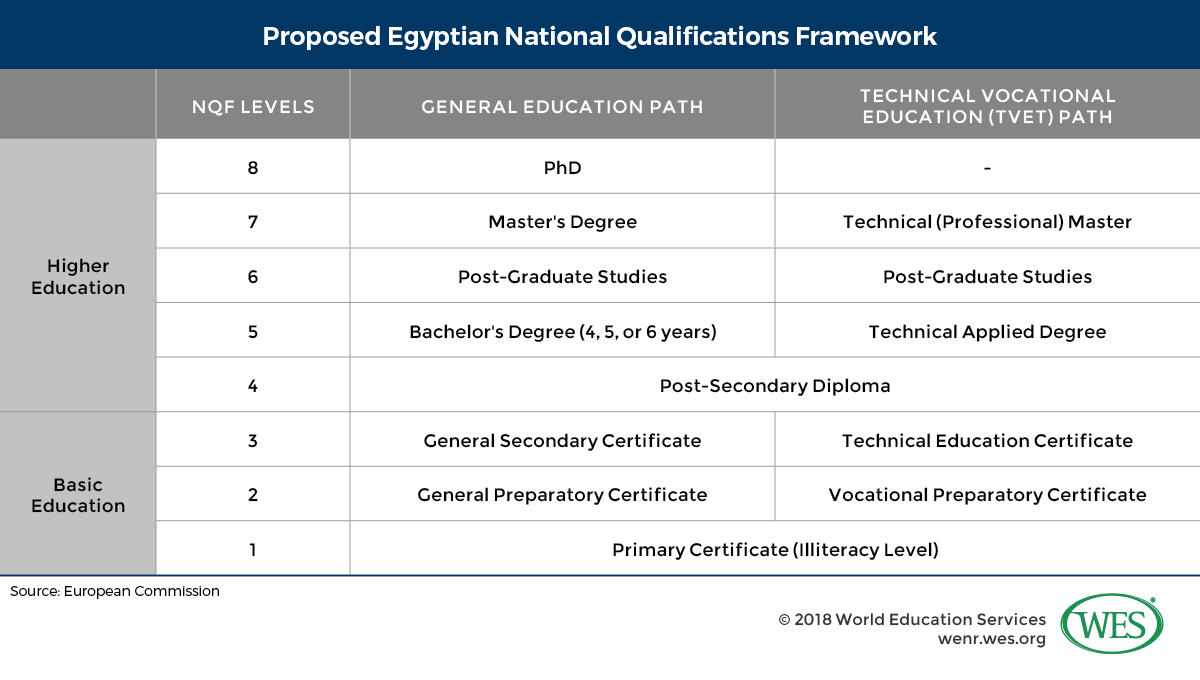

Egypt has a variety of higher education credentials, including diplomas, higher diplomas, bachelor’s degrees, postgraduate diplomas, master’s and doctoral degrees. The country is currently developing a national qualifications framework that categorizes higher education into five levels, as indicated below. Most students study in bachelor’s programs at universities. While some 350,000 Egyptians graduated with a bachelor’s degree in 2016, about 128,700 earned a diploma and only 20,185 and 9,016 students graduated with a master’s or doctoral degree, respectively.4

Technical Diplomas and Higher Diploma of Technology

Technical Diplomas (Diplom al-Fanni) are usually awarded after two years of study in vocationally oriented disciplines at technical institutes. Curricula are applied with no general education requirements. Examples of curricular specializations include construction technology, secretarial studies, or medical lab technology. The three-year Higher Diploma of Technology is awarded by higher technical institutes and some universities, typically in engineering disciplines. Graduates may be allowed to transfer into the third year of bachelor’s programs.

Bachelor’s Degree (Bakâlôriyûs)

Bachelor’s programs are four years in length in most disciplines, but programs in engineering, pharmacy, dentistry, and veterinary medicine last five years, while medical programs are six years in duration. Curricula are fairly standardized and require few if any general education courses; compulsory subjects outweigh electives. However, the longer programs in professional disciplines may include a preparatory year that covers general subjects, mostly related to the field of study. Some universities but far from all use a credit hour system that defines a year of study as 30 to 36 credit hours.

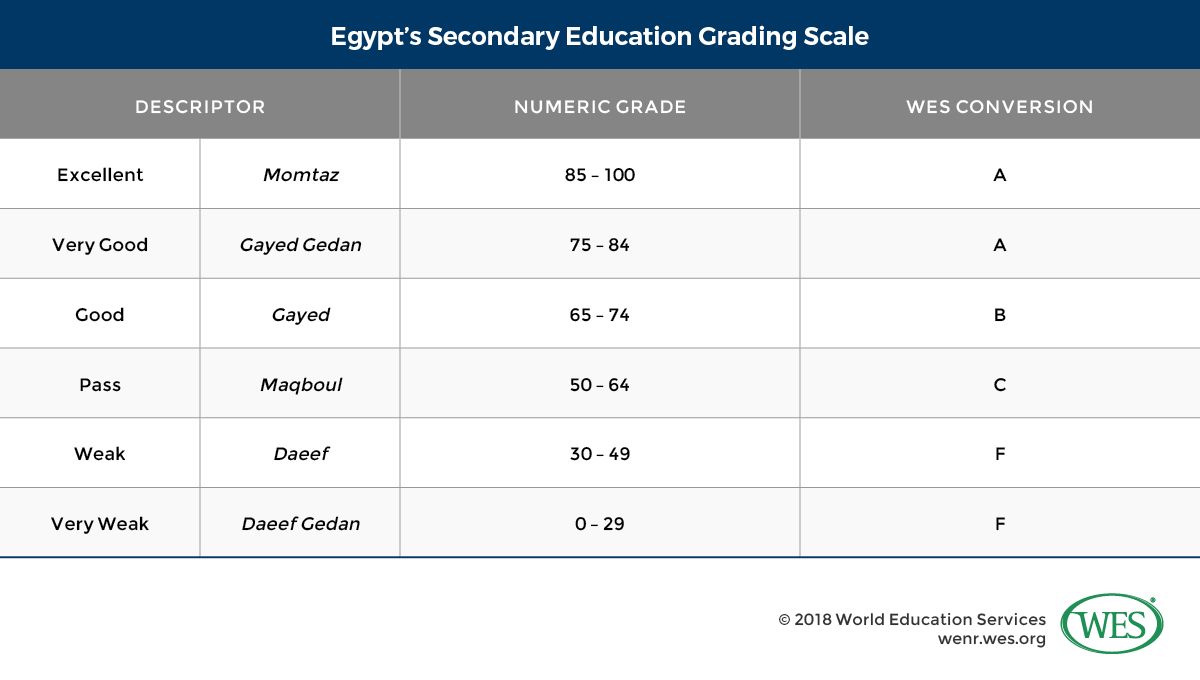

Progression to the next year of study and graduation is based on examinations; a thesis is usually not required. Grading scales vary widely by institution and faculty and include numerical 0–100 scales, U.S.-style A to F scales, and the European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System scale. A grade average of at least 50 percent of the total mark is generally required for graduation.

Bachelor’s programs are offered by universities and higher institutes. Distance education and online learning are slowly becoming more prominent, but are generally uncommon and not well respected by Egyptian employers.

Master’s Degree (Mâjistêr) and Graduate Diploma

Graduate degrees are almost exclusively awarded by universities. Master’s programs are usually two years in length, but some three-year programs also exist. Unlike in the case of undergraduate programs, admissions requirements are not set by the ministry and vary by institution, but include at least a bachelor’s degree earned with sufficiently high grades, usually in a related discipline. Most programs include a thesis and involve 30 to 42 credit hours of course work completed in the first phase of the program (at institutions that use a credit system). Some programs may be taught in English.

In addition to master’s degrees, there are higher diplomas (Diplom ad-Dirasaat al-A’aliyya), which may also be called postgraduate diplomas, graduate diplomas, or something similar. These programs are typically designed for further specialization after a bachelor’s degree earned in a more professionally oriented discipline. Programs are mostly one year in length, but may also require two years of study. Higher diplomas are usually designed for employment and do not provide access to doctoral programs.

Doctoral Degree

The doctoral degree (Dukturâh) is a terminal research qualification earned after two to five years of study. Admission requires a master’s degree in a related discipline, and other requirements, such as demonstrated foreign language abilities, may also apply. Some doctoral programs require the completion of some course work, but they may also be pure research degrees. They conclude with the defense of a dissertation.

Education in Medical Professions

Entry-to-practice qualifications in professional disciplines like medicine, dentistry, or veterinary medicine are currently earned by completing long, single-tier university programs of five or six years. Credentials include the Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery, the Bachelor of Dental Medicine and Surgery, and the Bachelor of Veterinary Medical Sciences. Physicians are trained at one of Egypt’s 27 dedicated medical university facilities, admission to which is highly competitive.

To date, medical programs are six years in length and usually divided into three years of pre-clinical studies followed by three years of clinical studies and a mandatory one-year internship. However, the Supreme Council of Universities is currently phasing in a new, more integrated five-year curriculum that will be followed by a two-year clinical internship. Medical specialties require another two to four years of clinical training and conclude with the awarding of a master’s degree, higher diploma, or Fellowship of the High Committee of Medical Specialties.

Teacher Education

Teachers are trained at dedicated university faculties of education. A bachelor’s degree is required to teach for all levels of school education. Applicants are assigned to faculties by the MOE based on their scores in the thanawiya amma examination. Programs are four years in length and incorporate general studies in the area of curricular specialization, pedagogical subjects, and in-service teaching internships in the third and fourth years of the program. Alternatively, candidates can earn a teaching qualification by completing a one- or two-year postgraduate diploma in education in addition to earning a bachelor’s degree in another discipline. To teach at public schools, graduates must pass further examinations to become licensed after working for two years as assistant teachers.

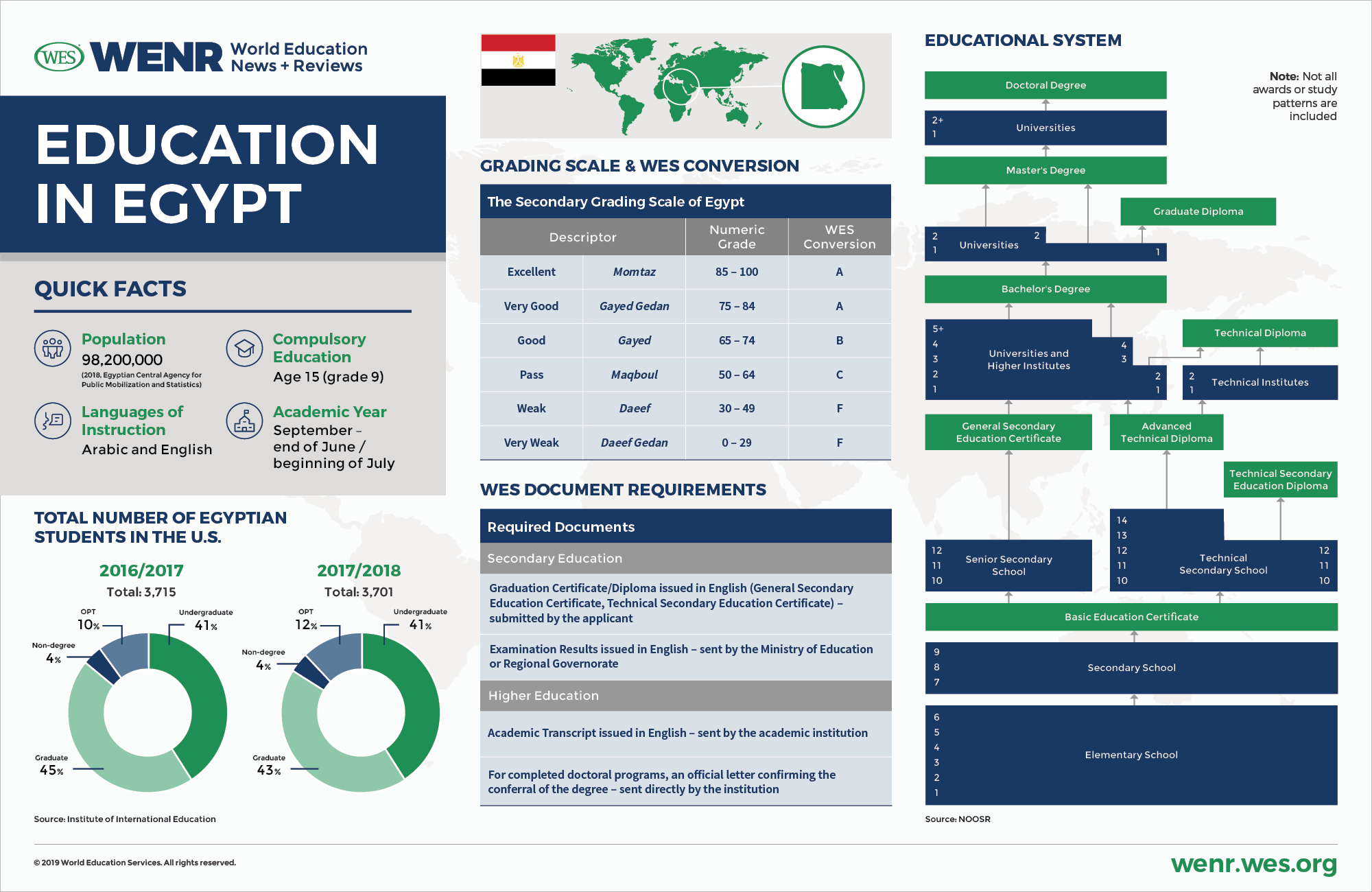

WES Documentation Requirements

Secondary Education

- Graduation Certificate/Diploma issued in English (General Secondary Education Certificate, Technical Secondary Education Certificate) – submitted by the applicant

- Examination Results issued in English – sent by the Ministry of Education or Regional Governorate

Higher Education

- Academic transcript issued in English – sent by the academic institution

- For completed doctoral programs, an official letter confirming the conferral of the degree – sent directly by the institution

Sample Documents

Click here for a PDF file of the academic documents referred to below.

- General Secondary Certificate

- Higher Diploma of Technology

- Bachelor’s degree

- Bachelor’s degree (engineering)

- Bachelor of Dental Medicine and Surgery

- Master’s Degree

- Doctoral Degree

1. Note that student mobility data from different sources such as UNESCO, the Institute of International Education, and the governments of various countries may be inconsistent, in some cases showing substantially different numbers of international students. This is due to a number of factors, including data capture methodology, definitions of “international student,” and/or types of mobility captured (credit, degree, etc.).

2. Other sources report slightly different years for when the university was established.

3. These were Ain Shams University, Al-Azhar University, Alexandria University, the American University in Cairo, and Cairo University.

4. Based on statistics from Egyptian Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics