A New Quality Control Regime in Indian Higher Education?

Stefan Trines, Research Editor, WENR

Why the Modi Government Wants to Scrap the UGC and Why Critics Condemn the Planned Reforms

In July 2018, the Indian government introduced draft legislation called the Higher Education Commission of India Act. If ratified, this new law would put the University Grants Commission (UGC), India’s main higher education oversight body, out of the business of quality control. Indian media have labeled the law a “UGC-killer reform,” since it would introduce sweeping changes in university oversight and transfer the UGC’s quality assurance responsibilities to a newly established Higher Education Commission (HECI)—a body that would be more directly controlled by India’s central government.

These far-reaching planned reforms have provoked scathing criticism in India. The attempt to tighten central government control over state universities in India’s 29 states has been condemned as “a classic example of a remedy worse than the disease. The legislation seeks to … rob … universities of whatever little autonomy they have.”

It’s presently unclear if the bill will be brought to a vote, and, if so, whether it will happen before India’s general elections, which will be held between April and May 2019. Not only does the proposal face considerable opposition in India’s parliament, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party has recently slipped in popularity, causing the BJP to lose a number of state elections in December 2018.

Although most observers still project Modi to win the general elections, the political perils of attempting to drastically alter quality assurance (QA) mechanisms in Indian higher education are well illustrated by previous failures. In 2011, opposition to reform proposals deemed “detrimental to the federal nature of [the] Indian polity” led to the withdrawal of an ambitious bill that sought to merge all of India’s QA bodies into one centralized agency. The episode demonstrated the substantial power that India’s states wield in the country’s bicameral legislature—which means that support for greater centralization in university oversight remains anything but certain. The governments of Tamil Nadu and Telangana have already condemned the new reforms.

To better understand the current reform legislation and the surrounding controversies, this article takes a closer look at the proposed changes and why they are so vehemently opposed. We’ll briefly describe the UGC, its functions, and the motivations to replace it, as well as the arguments of the reform’s opponents. University oversight in Indian higher education is an important topic, since the economic future and well-being of India and its surging youth population depend to a large extent on the quality of its education system and academic institutions.

What Is the UGC?

Formally established as a government body in 1956 and modeled after the now defunct British University Grants Committee, the UGC is essentially an autonomous government agency that channels public funds (grants) to higher education institutions in exchange for their compliance with set quality criteria. The UGC seeks to ensure homogeneous quality standards in Indian education and to coordinate QA policies between universities. It’s also an advisory body to the Ministry of Human Resource Development (MHRD), which oversees the commission, although the UGC is, again, essentially autonomous.

The UGC’s QA functions cover a wide range, including the regulation of admission requirements, program structures, curricula, and the hiring of faculty. Indian universities are subject to UGC inspections, and they must be formally recognized by the body in order to award degrees. The total amount of grant funds disbursed by the UGC amounted to nearly USD$1.5 billion in the 2016/17 academic year.

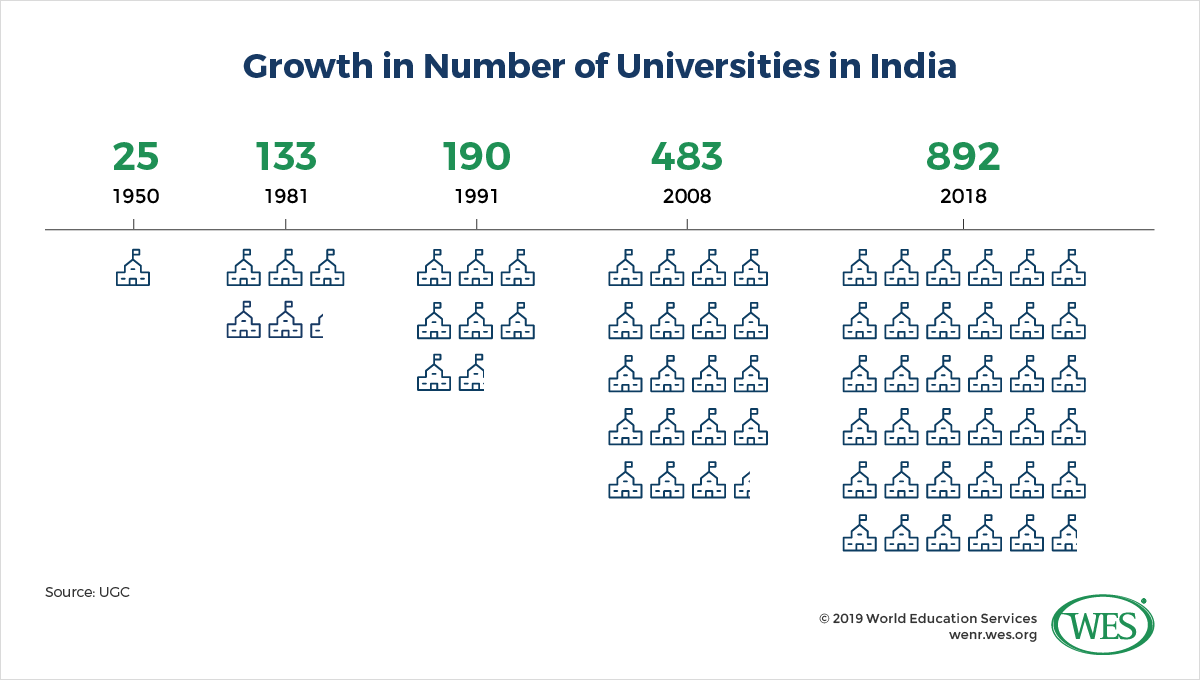

Given the rapid expansion of India’s education system (see chart below), the UGC oversees an ever-larger number of institutions. It currently recognizes 892 universities and other types of degree-granting institutions, including central and federal universities (established by the central government), state universities, private universities, autonomous colleges, and deemed-to-be universities, which are non-university institutions—both public and private—that are considered top quality. There were only 431 universities in India just a decade ago, in 2008.

But while the UGC is the main QA body in Indian higher education, it is just one of several regulatory bodies, including the All India Council for Technical Education (AICTE), which oversees technical and business education at higher education institutions (HEIs), the National Council for Teacher Education, the Distance Education Bureau, and others that oversee the licensed professions.

In addition, there are two accreditation agencies: the National Assessment and Accreditation Council (NAAC), an autonomous body under the UGC; and the National Board of Accreditation, established by the AICTE. State governments also play an important role in steering higher education in various forms. One problem with QA in the highly bureaucratic Indian polity—and one that is well understood by the Indian government—is that there are too many different regulators representing sometimes overlapping and competing responsibilities.

In light of these complexities and redundancies, the MHRD considered centralizing QA and merging the UGC and the AICTE until very recently. However, it ultimately decided on the HECI because an all-out merger would have been politically unfeasible, given the failure of the previous government to create a unified National Commission for Higher Education and Research in 2011.

The politics of education in India are contentious and intricate, so that major reforms can be difficult to implement, especially in a linear fashion. As the British Council put it, there “is a complex interplay beneath the formal structures affecting the distribution of power and resources in education in India; underlying pressures, interests, incentives, and institutions can influence or frustrate future educational change.” That said, some reports suggest that the government still plans to eventually merge the UGC with the AICTE despite the current HECI legislation.

Modi’s Reform Direction in Higher Education

Modi’s BJP was elected on a business-friendly platform of “less government and more governance.” That said, five years on, the size of government in India has not been clipped in a radical fashion. Despite Modi’s official mantra that “government has no business to do business,” the central government has been reluctant to privatize state-owned companies. Instead, it has raised taxes and increased regulations in some parts of the private business sector, as well as proposed an expansive public health insurance scheme dubbed “Modicare.” In the economic sphere, the BJP has a “policy preference … in favor of persistent and creative incrementalism, rather than big bang.”

On the other hand, the administration rolled back a host of environmental and labor protections, and decreased funding for elementary and secondary education as a percentage of overall government spending. In terms of style, the government adopted a “centralized and technocratic approach in order to expedite political decision-making by the executive.”

In line with this approach, Modi has sought to implement a flurry of reforms in higher education, many of them intended to strengthen the hand of the central government in university oversight, while simultaneously allowing for greater privatization and greater autonomy for top-ranked institutions.

Given the BJP’s emphasis on slim and transparent government, the UGC is seen as a bloated, inefficient organization that the Modi administration set its sight on even before the HECI legislation: The MHRD recently established alternative funding mechanisms (infrastructure loans provided directly by a new Higher Education Financing Agency under the MHRD) that would make HEIs less dependent on UGC grants, even though the new funding is given in the form of loans instead of non-repayable grants.

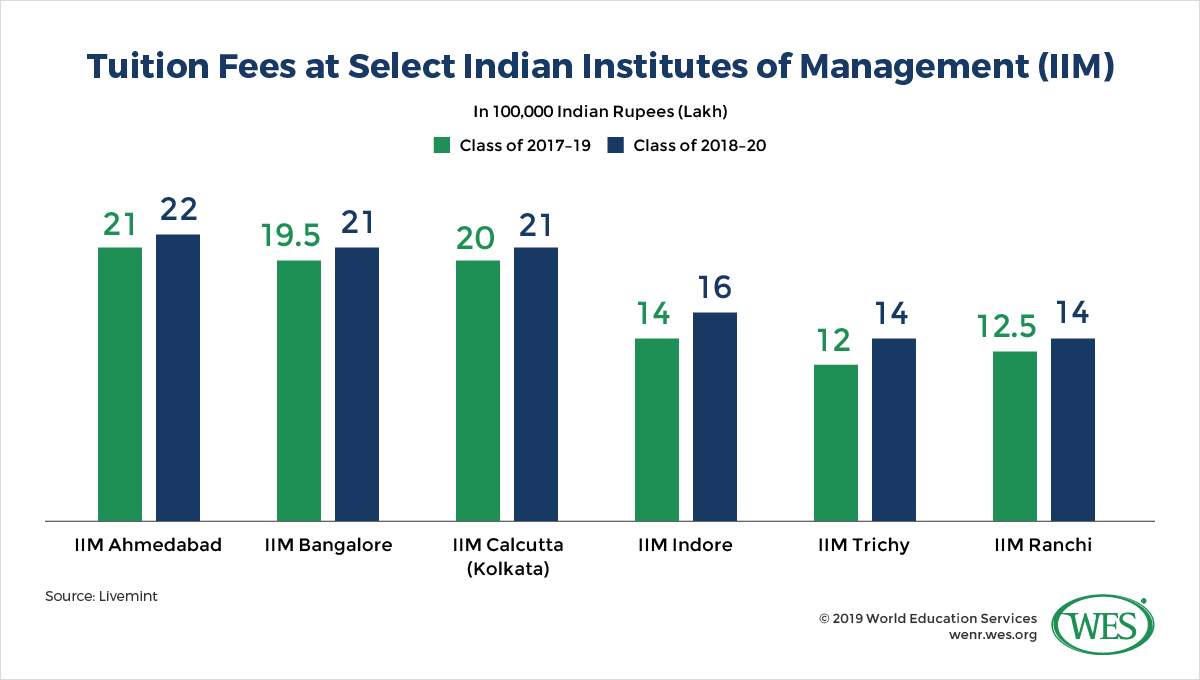

Further curtailing the reach of the UGC, a three-tiered graded autonomy scheme that frees eligible top-tier institutions (as measured by NAAC grade scores) from various UGC regulations1 has been introduced by the MHRD. In exchange, these institutions are expected to establish funding systems that make them less reliant on public funding, and offer all of their newly established degree programs in “self-financing mode”—a move that is bound to commercialize education and lead to higher tuition fees.

A similar autonomy scheme for India’s Institutes of Management (a group of top business schools) already caused fee hikes at several of these institutions. While the MHRD hails the autonomy schemes as a vehicle for innovation and modernization, others have derided them as a “Trojan horse for privatization.”

The HECI Act

Irrespective of what one thinks of the current reform directions under Modi, it’s clear that substantial changes are necessary in India’s mushrooming higher education system, which is overburdened by surging demand and characterized by severe shortcomings in quality. The system is highly uneven with a few elite institutions but many more that are lackluster. As former MHRD minister Shashi Tharoor has noted, it consists of “islands of excellence floating in a sea of mediocrity.”

In recognition of these disparities, the Higher Education Commission of India Act, 2018 (Repeal of University Grants Commission Act, 1956) calls for “promoting uniform development of quality of education in higher educational institutions … [and a central body] that lays down uniform standards, and ensures maintenance of the same through systematic monitoring.”

This is not a new objective, of course—the UGC has very much the same goal. However, besides being an obstacle to more direct federal control, the UGC is considered an outdated, inflexible administrative behemoth. The Modi administration portrays the UGC as an overly bureaucratic agency that is too powerful and too controlling in academic matters, since it simultaneously holds the purse strings.

Under the new system, by contrast, grant funds would be distributed by a new, yet-to-be-named separate grants commission, while regulatory oversight would be provided exclusively by HECI. Splitting quality control from grants administration is seen as a more robust and focused approach. HECI is also expected to regulate HEIs in a less bureaucratic and stifling manner. The MHRD has promised the end of the “inspection Raj”: The new HECI, envisioned to have a smaller staff and leaner administration, is designed to rely on the evaluation of objective performance criteria without having to conduct site inspections.

Notably, HECI’s functions are legislatively more concretely defined than those of the UGC. Specifically, HECI is tasked with setting “learning outcomes for courses of study in higher education” and to “lay down standards of teaching/assessment/research,” and to “specify norms of academic quality” that universities need to comply with when partnering with affiliated teaching colleges—the latter reflecting recent efforts to ramp up QA oversight over non-degree-granting teaching colleges. Since 2012, all of India’s more than 40,000 affiliated colleges have been mandated to seek NAAC accreditation.

Furthermore, the draft law specifies that all new degree-granting HEIs established in India must seek approval from HECI, which—unlike the UGC—has sweeping powers to unilaterally close down or otherwise penalize institutions that don’t comply with its regulations. This is a significant departure from current practice, since it would bar state legislatures from setting up HEIs without prior approval from HECI. In fact, the MHRD initially proposed that all existing HEIs, including state universities, apply for re-evaluation to obtain HECI approval within three years after the establishment of the new commission. But it backed down from this proposal amid sharp criticism from Indian state governments.

Furthermore, the draft law specifies that all new degree-granting HEIs established in India must seek approval from HECI, which—unlike the UGC—has sweeping powers to unilaterally close down or otherwise penalize institutions that don’t comply with its regulations. This is a significant departure from current practice, since it would bar state legislatures from setting up HEIs without prior approval from HECI. In fact, the MHRD initially proposed that all existing HEIs, including state universities, apply for re-evaluation to obtain HECI approval within three years after the establishment of the new commission. But it backed down from this proposal amid sharp criticism from Indian state governments disdainful of greater central supervision.

Accreditation and performance measurement of HEIs feature prominently in the draft bill as well. While it is unclear how this would affect the NAAC, the act calls for putting “in place a robust accreditation system for evaluation of academic outcomes by various HEIs” and the “closure of institutions” that “fail to get accreditation within the specified period.” It also proposes to “lay down norms and standards for performance-based incentivization” of HEIs, and “mechanisms to measure the effectiveness of programs and employability” of graduates. It can be expected that performance against such benchmarks will form the basis for federal grant allocations in the new system.

An Instrument of Privatization and a Tool of Federal Control: What the Critics Lament

The latter aspect has been criticized as a market-driven approach to university funding that will herald the commercialization of Indian academia. Vikram Singh, national secretary of the Students’ Federation of India, fears that HECI’s assessment criteria are too mechanistic and detrimental to academic quality: “The whole approach is focused on the accreditation and yearly evaluation of higher education institutions that will create a system of over-regulation.… This is an approach to facilitate further commercialization of education through a corporate approach to the education sector which focuses on homogeneous, one-size-fits-all administrative models.”

Singh also fears that the central government could instrumentalize HECI to punish institutions that are overly critical of the BJP. India’s Communist Party, likewise, has rejected the reforms as an “instrument to appease corporate interests” and “attract private sector investment in higher education.”

Other critics consider the HECI Act a hubristic power grab by the central government. The Indian legal news publication Legaldesire writes that the “purpose of the HECI can be interpreted as a tool to empower the center and reduce the states to being functionless. India’s area and diversity does not enable excessive centralization to be an improvement of academic standards. Rather, it will lead to even more corruption, bureaucratization, and red tapism.”

Despite the government’s promises of greater autonomy for HEIs, many academics fear that HECI will instead stifle the independence of universities. The Delhi University Teachers’ Association, for instance, noted that it’s “not clear how shifting grant functions to the Ministry will result in less interference. On the contrary, we fear that it will result in an increased direct interference.… The proposed Act mandates the HECI to promote autonomy of higher education institutions. However, this cannot be achieved if the Commission is allowed to micromanage institutions by even deciding learning outcomes of courses of study.”

Are the HECI Criticisms Warranted?

While there is validity to many of these arguments and the topic is debated passionately in India, looking in from the outside, we feel that some of the criticisms are somewhat exaggerated. Yes, as in other cash-strapped developing countries inundated by the surging demand for education, the private education sector in India has grown strongly under Modi—fully 82 percent of new colleges established in 2017 alone were private institutions.

Unsurprisingly, given its economic agenda, the BJP seeks to deregulate parts of the education system and stimulate private investment in the tertiary sector, while measures like the autonomy schemes are bound to increase costs for students and may also deepen disparities between elite institutions and the rest of the system. However, it would be an oversimplification to assume that the BJP is pursuing the wholesale privatization and predatory sellout of the higher education system.

To be sure, public education spending in India is vastly insufficient to meet existing needs. It remains far below expenditure levels of other countries at comparable levels of development, nominal increases in spending notwithstanding. However, the Modi administration has adopted a number of measures to soften the social impact of its policies, and it maintains a firm regulatory grip on both private and public HEIs despite the new freedoms afforded in current autonomy schemes.

For instance, the MHRD this year extended mandatory admission quotas for scheduled castes and tribes to private institutions, and has sought to curb tuition fee hikes at IIMs—steps that are hardly the hallmark of an unfettered deregulation bonanza. In education, the Modi government is executing its vision of “less government, more governance” in relatively modest ways, not in an overly radical fashion.

The same goes for the new HECI legislation. Faced with fervent criticism from state governments, the MHRD backed down from its original concept of centrally controlled funding, so that grants are now expected to be distributed by an independent agency rather than the Higher Education Financing Agency under the direct control of the MHRD, as was planned initially.

And in the final analysis, the quality-focused dual track approach of giving top-performing institutions greater academic autonomy while subjecting other HEIs to more stringent oversight by the central government may not be the worst approach to take in the context of India’s rapidly growing education system, even if there are flaws in the overall design. It’s doubtful that alternative models, such as devolving authority to India’s diverse states, can yield a nationwide system of consistent quality under the present circumstances.

That said, the HECI legislation will not be a panacea for core problems in Indian QA, such as regulatory overlap and diffusion in India’s fragmented yet bureaucratic and micromanaged system. Changes that are more fundamental than the HECI reforms will be needed to improve quality control in India’s disparate and mushrooming higher education sector. Even if they should be enacted, the HECI reforms will not be the last word in reforming QA mechanisms in India.

1. There are presently 60 HEIs that were granted autonomy. Category 1 autonomy requires a NAAC rating of 3.5 or higher and gives institutions the freedom ” to start new courses, new departments, off-campus centres, research parks, appoint foreign faculty, admit foreign students, pay variable incentive packages to their teachers and enter into academic collaboration with top 500 universities of the world without seeking UGC’s permission”. (MHRD minister Prakash Javadeka).