Stefan Trines, Research Editor, World Education News & Reviews

Introduction

As the largest country in Europe, Germany has, in the wake of recent events like the ongoing refugee crisis, the European sovereign debt crisis, and even the British Brexit vote, been in the spotlight. All of these developments have the potential to slow down (if not reverse) the European integration process – an issue of considerable concern to Germany, which has historically been a significant driver and benefactor of European integration.

The rapid aging of Germany’s population of 82.1 million is another looming concern. In 2015, Germany had the world’s second oldest population after Japan, with 28 percent of its citizens aged 60 years or over [2]. The Federal Statistical Office of Germany estimates [3] that the population will decline to a total of 67.6 to 78.6 million people by 2060. Even in the best case scenario, the decline would result in a decreased working-age population, which could undermine the government’s ability to fund public services and weaken the country’s economic foundations.

Given these challenges, it is no surprise that the German government has made the internationalization of higher education a strategic objective. Internationalization has various benefits ranging from positive impacts on the quality of research and education to enhancing the global reputation of academic institutions. It also has a number of economic “spill over” effects. It can help alleviate Germany’s skilled labor shortages and stimulate immigration. As illustrated by a detailed 2013 study [4] commissioned by the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD), foreign students in Germany yield a considerable economic net gain for society. This holds true despite high public expenditures on foreign students, and the fact that German universities charge virtually no tuition fees, even for international students.

International Student Mobility

Factors like the absence of tuition fees and a reputation for high-quality education, particularly in engineering and natural sciences, have helped Germany become an increasingly attractive country for mobile students seeking education abroad. According to UNESCO [5], Germany in 2013 attracted five percent of the world’s international students and was the 5th most popular destination country after the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, and France. International student arrivals have since increased. Germany is also an increasingly significant source of outbound international students.

Germany as an Education Destination

Between 2013 and 2015, the number of international students enrolled at German institutions rose from 282,201 to 321,569, an increase of almost 14 percent [6]. In 2015, China was the largest source country, accounting for 12.8 percent of inbound students, followed by India and Russia with 4.9 percent each [7]. U.S. students only accounted for 1.7 percent of international enrollments in Germany. Despite increased interest in Germany as a study destination over the past decade, North American students prefer more popular European destinations [8] like the United Kingdom, Spain, Italy, and France.

The German government seeks to further increase the country’s international student population to a total of 350.000 students by 2020. A joint position paper [9], issued by the federal and state governments in 2013, calls for the “strategic internationalization” of universities, better integration of foreign students, and increased funding for transnational partnerships and international marketing. It also advocates expanding the number of English-taught degree programs at German universities. This recommendation stems from the fact that mandatory German language requirements for most degree programs represent a substantial obstacle to enrolling foreign students. The number of English-taught master’s programs has increased considerably in recent years [10] and currently accounts for approximately ten percent of all programs. Undergraduate-level programs, on the other hand, are still taught almost exclusively in German.

The German government has also adopted immigration policies that support its efforts to internationalize higher education. The 2012 implementation of the European “Blue Card” legislation was a major step, since it gives qualified international graduates of German universities a pathway to permanent residence and access to the labor markets of most EU member states.

One of the most significant developments for the further internationalization of German higher education is the recent mass arrival of Indian students on German campuses. India is, after China, the second largest sending country of international students worldwide, and the number of mobile Indian students is projected to grow. Between 2014 and 2015, Indian enrollments in German institutions of higher education grew by a remarkable 24.4 percent to a total of 11,655 students [7], and India overtook Russia as the second largest country of origin for foreign students studying on German campuses. In light of these trends, some researchers predict [11] that Germany could soon overtake the UK to become the largest market for international education in Europe.

Germany as a Country of Origin

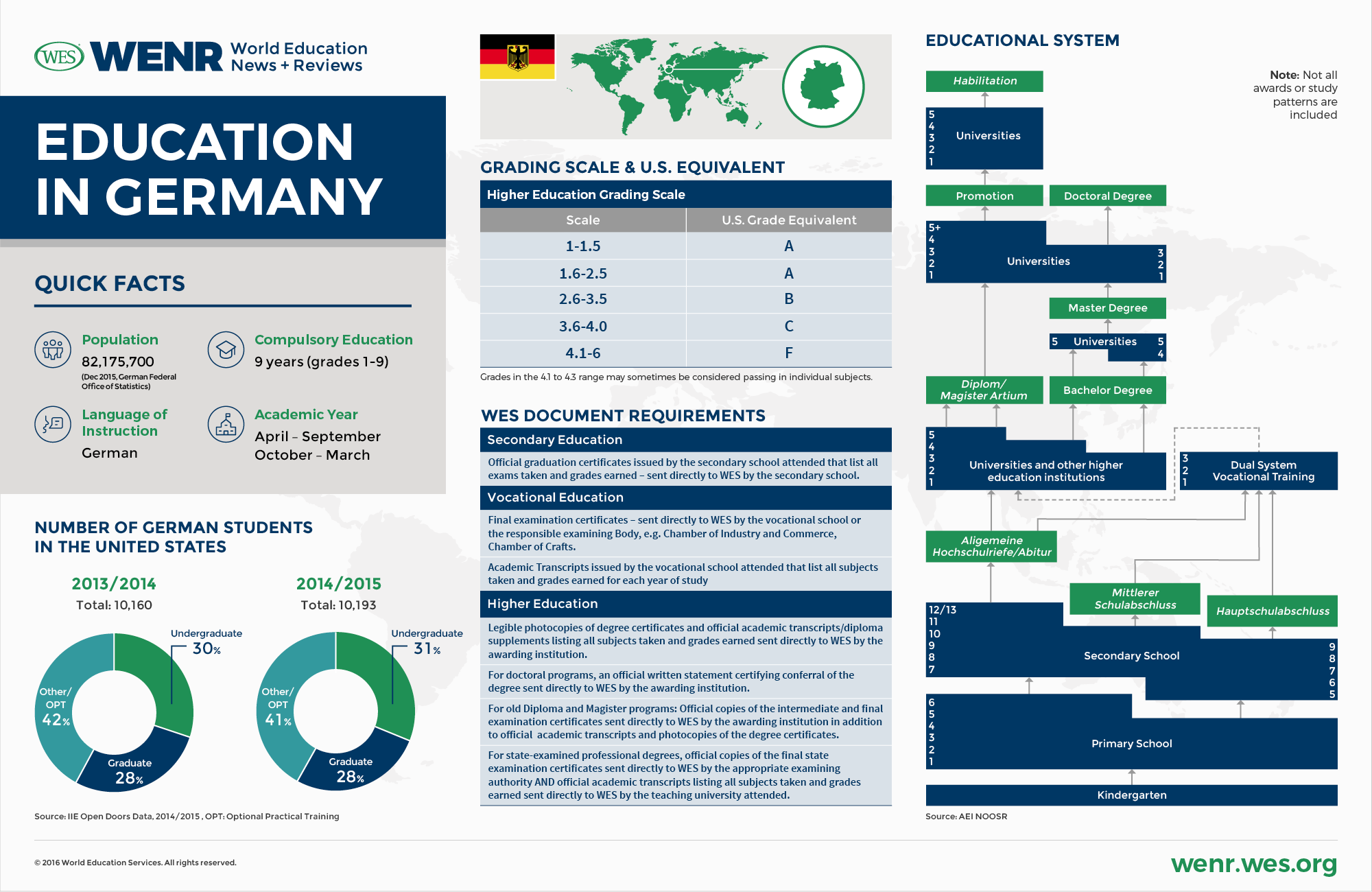

Underscoring Germany’s growing importance in international education is the fact that it is not only a top destination for foreign students, but also one of the largest source countries [5] for international students headed abroad. Overall, the number of Germans studying abroad increased by almost 400 percent [12] in the two decades following the country’s 1990 reunification. In 2013, Germany was the third largest sending country after China and India with 119,123 outbound students. Most of these students choose to stay close to home: Austria, the Netherlands, the U.K., and Switzerland are the top destinations for German students. The United States, with 10,193 enrolled German students as of the 2014/2015 academic year, comes in fifth place. (Germany currently represents the fourteenth largest country of origin [13] for foreign students in the U.S.)

In 2013, about one in three German graduates had some form of study abroad experience. This rate can be expected to grow. The German government seeks to increase the number of students with academic experience abroad to 50 percent by the end of the decade.

The Refugee Crisis & Access to Education

In terms of total numbers of refugees, no other country in the European Union has been impacted as much by the current refugee crisis as Germany. According to the interior ministry, the country in 2015 took in 890,000 refugees and received 476,649 formal applications for political asylum – the highest annual number of applications in the history of the Federal Republic. In 2016, the total number of refugees will be much smaller but may still reach up to 300,000, most of them from Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq.

Integrating such large numbers of migrants is a challenge for any society. The German government recognizes that access to education is vital for successful integration, especially since more than half of the current asylum seekers are below the age of 25. Approximately 325,000 school-aged migrant children between the ages of 6 and 18 are said to have entered Germany in 2014 and 2015. The German states in 2015 estimated that effective schooling of these children would require the recruitment of 20,000 additional teachers at a cost of €2.3 billion (USD $2.53 billion) annually [14]. In higher education, €100 million (USD $110 million) have been allocated [15] over the next four years to facilitate entry into study programs. The funds are used to ramp up financial aid, staffing in academic advising and public information campaigns, as well as expand the number of available language courses and seats in academic prep courses. The standard academic aptitude test for foreign students (TestAS) is now free for refugees and increasingly offered in Arabic. Since many refugees arrive without academic documents, the test can assist university admission, although gaining entry into a degree program often remains difficult due to language barriers and bureaucratic obstacles.

In Brief: The German Education System

Germany has a federal system of government which grants its 16 member states a high degree of autonomy in education policy. The Federal Ministry of Education in Berlin has a role in funding, financial aid, and the regulation of vocational education and entry requirements in the professions. But most other aspects of education fall under the authority of the individual states, or “Bundesländer”.

A federal law, the “Hochschulrahmengesetz,” provides an overarching legal framework for higher education. A coordinating body, the “Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education and Culture,” facilitates the harmonization of policies among states. Regulations and laws are consistent in many areas, but there can still be considerable differences in key areas. In the recent past, for instance, the length of the secondary education cycle varied from state to state. And different political approaches to tuition fees in different states meant that students in some states were paying €1,000 (USD $1,100) in annual fees while their peers across state lines studied for free.

Elementary Education

Compulsory education in Germany starts at age six, and, in most states, lasts for nine years. Elementary education is the only stage in German education where all students study at the same type of school. From grades 1 to 4 (grades 1 to 6 is some states), almost all German pupils attend “Grundschule” (foundation school), where they study the same basic general subjects. At the end of this foundation cycle, students move on to different types of lower secondary schools.

Pupils are assigned to schools based on academic ability. The process is commonly referred to as “tracking” or “streaming”. The mechanism by which they are tracked varies by state. Parents in most states can choose either to send their children to secondary schools in the vocational track, or to enroll them in university-preparatory schools. In some states, school recommendations influence the tracking. In other states, assignments are mandatory based on grade point average. Reassignments may still occur during an academic observation phase in grades 5 and 6.

This tracking process is not as rigid as it once was, and students in the vocational track can cross over to the university-preparatory track at a later stage. Some states have also established more integrated “comprehensive” secondary schools in which students in the different tracks study at the same school. However, the decision which school to attend remains an important factor in the academic career of many students.

Secondary Education

The secondary education system includes multiple programs at both the lower secondary and upper secondary levels. These programs emphasize either vocational skills or preparation for tertiary-level education, depending on the track.

Lower-Secondary Education – Vocational Track

Lower-secondary education along the vocational track imparts basic general education and prepares students for entry into upper-secondary vocational programs. The two most common school types in this track are the “Hauptschule” and the more popular “Realschule”.

- Hauptschule programs usually end after grade 9 and conclude with the award of the “Zeugnis des Hauptschulabschlusses” (certificate of completion of Hauptschule).

- Programs offered at the Realschule are academically more demanding and last until grade 10. Students graduate with the “Zeugnis des Realschulabschlusses” (certificate of completion of Realschule), sometimes also called “Mittlere Reife” (intermediate maturity). This certificate gives access to a wider range of vocational programs and also allows for access to university-preparatory upper-secondary education.

Upper-Secondary Education – The Vocational “Dual System”

Germany has a variety of different vocational programs at the upper secondary level. One subset of these programs is similar to programs in the general academic track in that students receive full-time classroom instruction.

The most common form of secondary vocational education, however, has a heavy focus on practical training. More than 50 percent of German vocational students learn in a work-based education system. This so-called “dual system,” which combines theoretical classroom instruction with practical training embedded in a real-life work environment, is often viewed as a model for other nations seeking to address high rates of unemployment, particularly among youth. In times of high youth unemployment in many OECD countries, Germany has the second-lowest OECD youth unemployment [16] rate after Japan – a fact often attributed to the dual system.

Students in the dual system are admitted upon completion of lower-secondary education. The system is characterized by “sandwich programs” in which pupils attend a vocational school on a part-time basis, either in coherent blocks of weeks, or for one or two days each week. The remainder of students’ time is devoted to practical training at a work place. Companies participating in these programs are obligated to provide training in accordance with national regulations, and to pay students a modest salary. The programs last two- to three-and-a-half years, and conclude with a final examination conducted by the responsible authority in the field, often regional industry associations like the Chambers of Industry and Commerce and Chambers of Crafts.

The final credential awarded to dual system graduates is typically a formal, government-recognized qualification certifying students’ skills in regulated vocations. In 2015, there were 328 [17] such official vocations with titles ranging from “carpenter” to “tax specialist” to “dental technician” or “film and video editor.”

Many vocational schools also offer students a pathway to tertiary education via double qualification courses. Students who take this pathway earn a “Zeugnis der Fachhochschschulreife” (university of applied sciences maturity certificate), which qualifies them for access to a subset of higher education institutions, the so-called universities of applied sciences, as well as regular universities in a small number of states. The theoretical part of this program is commonly completed after 12 years.

NOTE: Some vocational programs have become popular with students who have obtained university entry qualifications on the academically oriented upper secondary track. One in four students [18] starting a vocational program in 2013 had previously earned a university entry qualification. Overall, however, enrollments in the vocational sector have declined [19] in recent years due to demographic changes and increasing numbers of students studying in the university-preparatory track.

Upper Secondary Education – University-Preparatory Education

When Germans refer to university-preparatory study, they often think of the “Abitur”, the important final examination, which concludes upper secondary education – and which often has a significant impact on students’ academic careers. Abitur programs predominantly take place at a dedicated type of school called the “Gymnasium.” Study at this school usually begins directly after elementary school. Programs include a lower-secondary phase (until grade 10) and an upper-secondary phase of two or three years. Together, lower, upper, and secondary education typically last 12 or 13 years. (See section below, Shortening of Upper Secondary Schooling: A Reversal of Reforms?, for additional discussion of the duration of secondary programs.)

The Gymnasium curriculum is designed to ensure “maturity” or readiness for higher education based on mandatory study of core subjects including: languages, literature and arts, social sciences, mathematics, and natural sciences. The program concludes with the rigorous written and oral final Abitur examination, which is overseen by the ministries of education of the states, most of which mandate standard content for one uniform examination taken by all students.

After successful completion of the exam, students receive the “Zeugnis der allgemeinen Hochschulreife” (certificate of general university maturity), a credential that gives graduates the legal right to study at a university. Since study in Germany is also mostly free, this may sound like an egalitarian educational utopia. In reality, however, admission to universities can be competitive. The final Abitur grade determines how quickly students get admitted to popular programs that have a fixed number of available spaces (numerus clausus). According to the German Foundation for University Admissions, the waiting period for admission into medicine programs was, as of 2015, seven years for students with lower grades.

Shortening of Upper Secondary Schooling: A Reversal of Reforms?

As an aging society, Germany has an interest in reducing the age of its students, which in 2013 were still among the oldest in the OECD. In the 1990s, one set of policy solutions focused on shortening the secondary education cycle and aligning Germany’s education system with the 12-year paradigm found in most of the world. Abitur programs in West Germany had traditionally been 13 years in length with an upper-secondary segment consisting of a one-year introductory period followed by a two-year “qualification phase.” Secondary education in former East Germany lasted only 12 years, but three out of five East German states adopted a 13-year system after reunification.

By the 2000s, however, all of Germany seemed on its way to the 12–year “Turbo Abitur.” Between 2001 and 2007 most states passed legislation to shorten the secondary cycle by one year, pledging to preserve quality standards by compressing the curricula and contact hours of the old 13-year programs into 12 years. Implementation plans differed by state. But in many cases, the old system of elective concentration subjects in the upper-secondary qualification phase was replaced with a more rigid system of three to six mandatory, four-hour “core subjects”, including mathematics, German and a foreign language.

What all of this meant was that German students, besides having fewer choices in subjects and specializations, had to spend more time in the classroom. On average, the time spent in class increased from 29 or 30 hours to 33 hours per week. Since this change has proven unpopular with parents, political opposition mounted. Laments included the “lost childhood” of Germany’s students, and more prosaic concerns about a decline in educational quality. As a result, a reversal or modification of the reforms is currently under way in a number of states. Lower Saxony is returning to a 13-year system this year and several other states, including Hesse, Schleswig Holstein and Baden-Württemberg, are currently experimenting with mixed systems allowing for both 12 and 13-year programs. It remains to be seen if this trend will lead to a widespread reintroduction of the 13-year system or – more likely – the coexistence of different systems in different states.

Tertiary Education

In recent years, Germany has experienced increased participation rates in university education in general, and a growth of enrollments at private institutions in particular. The German Office of Statistics [20] reported that the number of newly registered students (excluding foreign students) in the first semester of a degree program increased by more than 34 percent in the last decade – from 290,307 in 2005 to 391,107 in 2015. According to the statistics provided by the German Science Council [21], the total number of students attending German tertiary institutions in the fall of 2016 is 2,718,984.

Despite these gains, however, Germany still has below-average tertiary education entry and graduation rates compared to other industrialized countries. According to the OECD, 53 percent of young German nationals entered a tertiary education program in 2013, compared to an average of 60 percent among OECD member states. The depressed entry rate is attributable, at least in part, to Germany’s secondary vocational education system. Graduates from secondary-level German vocational programs – such as nursing, for instance – can legally work as entry-level professionals. In other countries, employment in these fields typically requires a tertiary degree.

While this fact relativizes the comparatively low entry rate at the tertiary level, however, it does not fully account for Germany’s graduation rates, which remain below average: Only 35 percent of all first-time tertiary German students (excluding foreign students) actually graduated with a degree, placing Germany in the third to last place in one 2015 OECD report1 [22].

NOTE: The emergence of a new segment of the private higher education sector has contributed to recent overall growth in German university enrollments. Religious private higher education institutions have existed in Germany for quite some time. The first of these institutions was founded at the beginning of the 20th century. Non-religious private higher education, on the other hand, is still a relatively new phenomenon and did not take hold on a larger scale until the late 1990s. Since then, the sector has expanded considerably. The number of non-faith based private universities increased from 23 in 1990 to 47 in 2000 [23], and reached 122 in 2016 [24] – about one third of all current German higher education institutions. In 1995, just 15,948 students enrolled at private tertiary institutions. By 2015, that number had grown more than elevenfold to 180,476 [25]. It should be noted, however, that the private sector still accounts for only 7.1 percent of Germany’s overall tertiary enrollment. Compared to the big public universities, private schools are often smaller and tend to offer specialized niche programs [26] that complement existing offerings rather than competing directly with public schools.

Types of Institutions

In addition to non-tertiary higher education and government schools, Germany currently has 396 state-recognized higher education institutions. The institutions are of two types: 181 universities and university-equivalent institutions, including specialized pedagogical universities, theological universities, and fine arts universities; and 215 so-called universities of applied sciences (Fachhochschulen).

The main difference between the two types of institutions is that the first set of institutions are dedicated to basic research and award doctoral degrees, whereas Fachhochschulen (FHs) are more industry-oriented and focused on the practical application of knowledge. Both institutions award Bachelor and Master degrees, but FHs do not have the right to award doctoral degrees. FH programs usually include a practical internship component and tend to be concentrated in fields like engineering, business, and computer science.

A further distinction lies in the admission requirements: Whereas a certificate of general university maturity is required for unqualified access to universities in most states, study programs at Fachhochschulen can be entered with a university of applied sciences maturity certificate earned in the vocational track.

In terms of enrollments, more than 60 percent of students in 2015 (1.756,452) studied at universities [21], while about one third of students (929,241) attended Fachhochschulen.

Transnational Education, German Style

Germany is a relative latecomer to the global practice of transnational education. The export of education programs has traditionally been the domain of Anglo-Saxon countries like the U.K. and Australia, which still hold most of the market share. The overall size of the TNE sector tends to be difficult to categorize and quantify [28], but a 2013 study [29] by the British Council estimated that, between 2011 and 2012, British institutions enrolled a total of 454,473 students in transnational programs, whereas German institutions only enrolled 20,000 students in transnational dual degree programs, international branch campuses, and foreign “German-backed universities.”

Aside from these quantitative differences, German TNE is qualitatively distinct in that is part of a long-term, government-subsidized internationalization strategy. (Many other initiatives are privately led and commercially oriented.) Transnational partnerships are not only viewed as beneficial for the global competitiveness of German universities, but also as a tool of development aid [30], designed to support academic capacity building in foreign countries. Until now, more commercially oriented modes of TNE, such as distance education, validation, and franchising models remain uncommon in Germany. Instead, German universities typically try to contribute to the modernization of the education system in the host countries. A common model is to partner up with universities that remain independent institutions in the home system while being closely associated with, and supported by their German “mentor universities”. The biggest of these German-backed universities is the German University in Cairo, which enrolled 10,491 students in 2014 [28]. Other German-backed universities [31] are located in Algeria, Hungary, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, Oman, Turkey, and Vietnam.

Funding and Oversight

According to the OECD, Germany invested 1.2 percent [32] of its gross domestic product in tertiary education in 2013. Given the dominance of public institutions in German higher education, it is not surprising that more than 85 percent [33] of financing came from public sources. The German Rectors Conference puts [34] the total amount of government spending on university education in 2010 at €23.3 billion (USD $25.6 billion), 85.4 percent of which was provided by the governments of the individual states.

Changes to this funding structure have been debated for some time. The OECD in 2016 went as far as calling the German model unsustainable [35], but solutions, especially those focused on tuition-based funding models, have been hard to find. The introduction of additional tuition fees by seven states in the 2000s turned into one of the more controversial topics in recent German higher education politics. Although the so-called “Uni-Maut” levied by public universities was modest by international standards, strong political opposition quickly led to the abolition of fees in all states by 2014. Private universities, by comparison, continue to charge tuition fees that go far beyond the average €500 (USD $550) that public universities were collecting per semester. In the private sector, €30,000 (USD $32,982) or more for a Bachelor’s degree is not uncommon. One institution, Jacobs University in Bremen is currently charging as much as €11,500 (USD $12,643) per semester.

Since the 16 German Bundesländer have legislative authority over university education, the role of the federal government in the funding of higher education has traditionally been limited. In recent years, however, both the federal government and the states have sought to expand the federal role in cases of “supra-regional importance.” One example of such increased financial intervention by the federal government is the so-called “Excellence Initiative,” a program in which Berlin provided the bulk of €4.6 billion (USD $5.06 billion) given to institutions between 2005 and 2017 to improve the global competitiveness of German universities. The funding was allocated to establish new graduate schools and create “clusters of excellence” that connect universities, industry and research institutes.

In 2012, 11 universities were selected to receive funding for their “future concepts” in promoting research. A number of these institutions are considered to be among Europe’s best universities. Seven of them are among the nine German universities included in the world’s top 100 universities in the current Times Higher Education world university ranking [36]. Overall, Germany’s place in this ranking has improved markedly in recent years. In 2016/2017, for instance, nine universities were included in the top 100; only six were included in the top 100 the year before.

Quality Assurance and Accreditation: A Work in Progress

Germany’s higher education institutions are generally recognized and regulated by the ministries of education in the individual states. In order to become state-recognized, private institutions must also be accredited by the “Science Council,” an advisory body to the federal and state governments.

Quality assurance mechanisms in Germany have undergone significant changes since the introduction of the European Bologna reforms at the end of the 20th century. In 1998, the German states jointly decided to add external program accreditation as a quality assurance mechanism for new bachelor’s and master’s degrees – a key concept of the Bologna reforms. There presently are ten independent accreditation agencies operating in Germany. These private agencies are in turn accredited by the German Accreditation Council, the designated supervisory public authority.

Almost two decades after the initial decision to introduce the reforms, program accreditation remains a work in progress, however. As of September 2016, less than 60 percent of all existing degree programs [37] were externally accredited. The accreditation process is slow and burdensome for universities, involving high direct and indirect costs.

The new concept of “system accreditation” has consequently become a popular alternative. First introduced in 2007, system accreditation allows institutions to forgo external program accreditation by creating internal quality assurance systems that are evaluated by the accreditation agencies. By 2016, 47 higher education institutions had obtained accreditation [38] of their quality assurance systems – a considerable increase compared to previous years.

System accreditation will likely continue to be a growing trend, as illustrated by the fact that a significant number of institutions currently have pending applications for accreditation. But how exactly the quality assurance mechanisms in Germany will develop in the long term is currently unclear. The Federal Constitutional Court this year added an element of uncertainty when it ruled the present accreditation system unconstitutional [39], as it transfers key functions of quality assurance from the government to private organizations.

Degree Programs: Implementing the Bologna Reforms

Until recently, any overview of German higher education had to include the old unified Diplom and Magister programs, which were the standard university degrees before the Bologna reforms. Today, the old programs have been phased out; they represent only about two percent of existing degree programs [40]. Almost all current students study in the same bachelor’s and master’s degree programs found in the other countries of the European Higher Education Area.

The first cycle bachelor’s degree is a three- to four-year program consisting of 180 to 240 European ECTS credits. The second cycle master’s degree lasts one to two years and entails 60 to 120 credits. Completion of both cycles nominally requires 300 ECTS, but universities may on occasion allow talented students to enter a 60 ECTS master’s program on the basis of a three-year bachelor’s degree.

In the third cycle, reforms have been slower. The Bologna declarations call for structured doctoral programs that include mandatory course work. Such programs do not have much tradition in Germany, where the degree of “Doktor” (Doctor) has historically been a pure research degree. As of now, unstructured individual programs remain the most common form of doctoral study. Most doctoral candidates still conduct independent research and prepare a dissertation under the supervision of a single professor.

In recent years, however, considerable efforts have been made to establish dedicated “graduate schools” that offer structured programs. These programs are often taught in English and involve a team of academic advisors. They typically last three years and include course work in addition to the dissertation. The new programs have sometimes been criticized as bringing about the “schoolification” of research. But the structured programs are quickly growing in popularity and will likely become more prevalent. The German government considers structured research programs conducive to academic quality and is currently subsidizing 45 graduate schools in the framework of the Excellence Initiative.

Professional Disciplines

Overall, Germany, like a number of other European countries, has so far been relatively reluctant to implement the Bologna reforms in the professional disciplines. Entrenched opposition in disciplines like medicine suggests that it may not be a foregone conclusion that the Bologna degrees will inevitably be introduced in all fields of study. State-examined programs in professions like law, medicine, dentistry, or veterinary medicine have, to a large extent, been exempted from the implementation of the Bologna degree structure. Many professional study courses are thus still long, single-tier programs. These programs take place at universities, but conclude with a government-administered examination. Instead of an academic degree, graduates earn a government-issued certificate of completion of state examination.

- Medical programs, for example, last six years and conclude with the award of a final “certificate of physician examination,” which entitles the holder to become licensed as a medical doctor. Splitting this program into bachelor’s and master’s cycles is currently not considered feasible, due to concerns about educational quality and questions regarding the employability of graduates with a first cycle Bachelor of Medicine degree.

- In the field of law, supplementary Bachelor/Master of Laws degrees have been introduced. But these degrees are usually more business-oriented than traditional law degrees, and do not grant full access to the profession.

- The discipline that has perhaps undergone the most significant changes is teacher education. Many German states have introduced bachelor’s and master’s programs that supplant the old curricula. Yet, government examinations remain in place even in these states. The degrees of Bachelor and Master of Education generally do not entitle to work as a teacher. To become licensed, degree holders must still complete a preparatory teaching service and sit for a final state examination.

Document Requirements

Secondary Education

Official graduation certificates issued by the secondary school attended that list all exams taken and grades earned – sent directly to WES by the secondary school.

Vocational Education

Final examination certificates – sent directly to WES by the vocational school or the responsible examining Body, e.g. Chamber of Industry and Commerce, Chamber of Crafts.

Academic Transcripts issued by the vocational school attended that list all subjects taken and grades earned for each year of study

Higher Education

Legible photocopies of degree certificates and official academic transcripts/diploma supplements listing all subjects taken and grades earned sent directly to WES by the awarding institution.

For doctoral programs, an official written statement certifying conferral of the degree sent directly to WES by the awarding institution.

For old Diploma and Magister programs: Official copies of the intermediate and final examination certificates sent directly to WES by the awarding institution in addition to official academic transcripts and photocopies of the degree certificates.

For state-examined professional degrees, official copies of the final state examination certificates sent directly to WES by the appropriate examining authority AND official academic transcripts listing all subjects taken and grades earned sent directly to WES by the teaching university attended.

Sample Documents

This file [41] of Sample Documents (pdf) shows the following set of annotated credentials from the German education system:

- Certificate of General University Maturity (University-Preparatory High School Diploma)

- Translation of the Certificate of General University Maturity

- Bachelor of Arts – Degree Certificate

- Bachelor of Arts – Academic Records Request Form

- Bachelor of Arts – Diploma Supplement

- Bachelor of Arts – Transcript of Records (Academic Transcript)

- Bachelor of Arts – Translation of Degree Certificate

- Bachelor of Arts – Translation of Transcript of Records

- Master of Science – Degree Certificate

- Master of Science – Transcript of Records (Academic Transcript)

- Master of Science – Examination Certificate

- Doctor of Philosophy – Degree Certificate

- Doctor of Philosophy – Translation of Degree Certificate

1. [42] See: OECD: Education at a glance. http://download.ei-ie.org/Docs/WebDepot/EaG2015_EN.pdf [43] Percentages based on first time tertiary entry and graduation rates excluding international students.