Stefan Trines, Research Editor, WENR

Iran is among the seven majority-Muslim countries whose citizens were, on January 27th, barred from entering the U.S. for at least 90 days by executive order of the Trump administration. The move harks back to 1979 when President Carter canceled the issuance of visas to Iranians and directed all Iranian students to report to immigration [2]. In the following years, Iranian enrollments all but dried up. The latest abrupt visa ban is now in the courts. If it is upheld, it is expected to be followed by aggressive vetting of visa applicants from Iran and the other named countries. At best, these policies will simply slow Iranian student movements to the U.S. At worst, they are a prelude to a prolonged freeze on enrollments from Iran and a drop in inbound mobility among students from around the world [3].

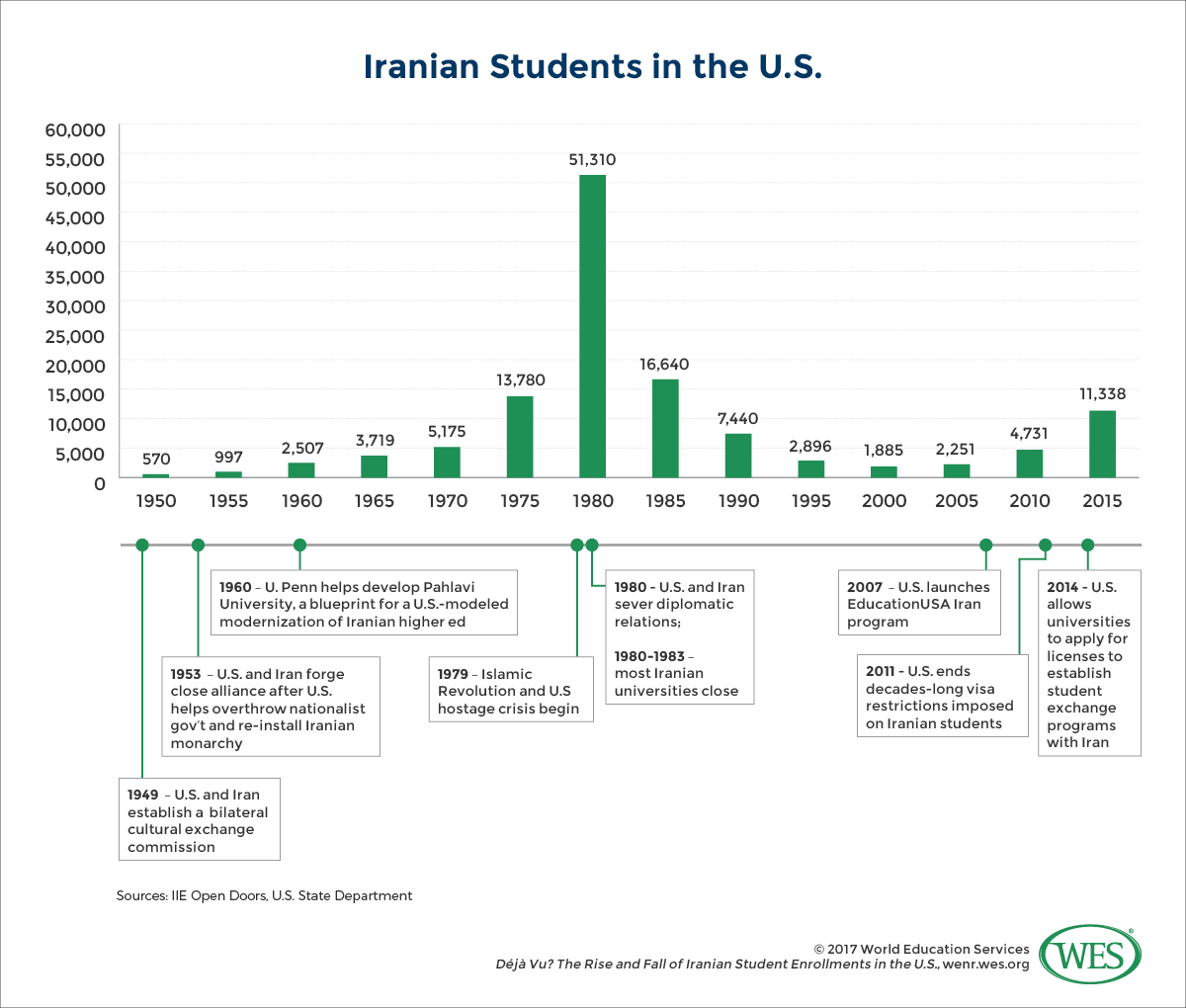

In 1979/80, Iran was – at least in terms of higher education – what China is today: the biggest sender of foreign students to U.S. universities. But that same year, the Islamic Revolution and an ongoing hostage crisis at the American Embassy in Tehran led the Carter administration to sever diplomatic relations. Without the abrupt break, Iranian student enrollments in the U.S. might have continued to build on the exceptionally strong growth rates of the 1970s; Iran might have remained a top source of U.S.-bound international students for years.

History turned out differently. As of the 2015/16 academic year, the flow of Iranian students to the U.S. was less than a quarter of what it was when relations were severed. And yet, despite the fact that Iran has been viewed as an enemy state by the U.S. government for almost 40 years, Iranian student numbers have been on the rise for more than a decade. In 2016, the Obama administration negotiated a resolution to the nuclear proliferation crisis in Iran and international nuclear sanctions were lifted. One artifact was widespread speculation about the possibility of more substantial increases in the number of Iranian student enrollments in the U.S.

The exclusionist immigration policies of the Trump administration make such a possibility unlikely. There is little question that Iran is now a dynamic growth market for international education. Existing push factors in Iran will almost certainly lead to continued growth in outward mobility, at least in the short term. But how long those push factors will remain in play – and whether Iran’s mobile youth will continue to come to the U.S. in large numbers in the future – remain open questions. Even if the U.S. visa ban is temporary, any additional immigration hurdles implied in the proposed “extreme vetting [4]” of visa applicants may prove an especially high bar for Iranian students, who, even in the recent past, had a harder time obtaining visas to study in the U.S. than they did in other countries.

As of writing, it seems probable that history will repeat itself: Despite the renewed potential for substantial numbers of Iranian students to study abroad, the U.S. will likely not become a major destination. Beyond formal immigration hurdles, the rhetoric of the Trump administration damages the image of the U.S. among students abroad. If current policies are any indication, we are bound to lose a large share of the mobile Iranian student population to other countries that are more welcoming to international students, and miss out on the potential economic, scientific [5], or other benefits that they generate.

Iran is widely viewed as one of the world’s most dynamic markets for international students, beyond the twin pillars of China and India. The British Council in 2014 found [6] that the number of Iran’s outbound postgraduate students showed strong growth in recent years, rising from 8,000 in 2007 to 17,000 in 2012. The total increase in that period was 112.5 percent — the fastest annual growth rate of any country besides Saudi Arabia. The Council predicted strong future growth in countries like the U.S., Germany, and Canada. Those projections have recently seemed to pan out. In the U.S., the number of Iranian postgraduate students grew by 33 percent between 2012/13 and 2015/16, from 7,157 to 9,534. (In 2015/16, a total of 12,269 Iranian students were studying in the U.S., according to the IIE’s Open Doors data. This is the largest number of Iranian students in the U.S. since 1985, and represents a 118 percent increase compared to 2010/2011.) [See also our companion article on the drivers of Iranian student mobility [7] in the current issue.]

Iran has a high rate of outmigration in general. According to the World Bank, [8] the country experienced a net outmigration of 300,000 people in 2012 and 549,000 people in 2007, respectively. The Iranian Ministry of Science, Research and Technology in 2014 announced that the country was losing about 150,000 talented citizens each year [9] and that 25 percent of Iranians with post-secondary education were living abroad in OECD countries. Measuring countries’ brain drain by patents filed by emigrants, The Economist magazine reported [10] in 2015 that 96.1 percent of worldwide patents by Iranian-born inventors were filed from abroad. Conservative political factions in Iran continue to look unfavorably on educational exchanges with the West, but the political environment in Iran was, at the end of 2016, more conducive to cooperation with Western academic institutions and student exchange than in previous decades. Given the exclusionary immigration policies and imposition of new sanctions [11]by the Trump administration, however, potential gains can now primarily be expected in Europe and other countries.

Iranian Students in the U.S.: Early Roots

The relatively short history of Iranian students in the U.S. cannot be told separately from the history of the two nation’s political relationship. Shortly after World War II, the U.S. government started to actively encourage student exchange with Iran. In 1949, the governments of the U.S. and Iran established a bilateral “Commission for Cultural Exchange between Iran and the United States [12]” tasked with promoting “…. a wider exchange of knowledge and professional talents through educational contacts.” Increased cultural and student exchange was, at that time, in the mutual interests of both countries. The U.S. sought a political ally in a strategically important world region, and the Iranian government sought to increase education levels and technical know-how in order to facilitate the modernization of the country. The two countries’ goals aligned in 1953, following the overthrow of the nationalist Mossadegh government, and the re-installation of the Iranian monarchy under Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlawi in a U.S.-orchestrated military coup.

Cultural exchanges flourished in the tailwind of the geostrategic partnership. The Iranian government actively promoted transnational partnerships with U.S. universities. In one highly visible example of these exchanges, the Shah in 1960 enlisted the University of Pennsylvania [13] to assist in the development of Pahlavi University in Shiraz, intended to serve as a blueprint for a U.S.-modeled modernization of Iranian higher education institutions. Shiraz University, the successor institution of Pahlavi University, remains one of Iran’s top universities today. The U.S. had a strong influence on the formation of the modern Iranian education system, which still maintains many structural similarities to the U.S. system of education. (See the related WENR profile of the Education System in Iran [1].)

The 1950s-1970s: Expansion of Iranian Student Mobility to the U.S.

The Iranian government also encouraged international student exchange. Between the 1950s and the 1970s, Iranian students began flocking to the U.S., and by the mid-1970s, Iran emerged as the world’s top sender of foreign students to the United States. Between 1974/75 and 1982/83, Iranians constituted by far the largest group of foreign students in the U.S.http://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/red-tape-iron-nerve-the-iranian-quest-for-u.s.-education [15].

In 1979/80, the number of Iranian students reached its peak with a total of 51,310 students – almost three times as many students as came from Taiwan, then the second-largest supplier of U.S. enrolled international students and another ally of the United States.http://www.iie.org/Research-and-Publications/Open-Doors/Data/International-Students/All-Places-of-Origin/1950-2000 [16]. Zikopoulos, Marianthi: Detailed Analysis of the Foreign Student Population, 1989-1990. Institute of International Education, New York. Accessed December 2016, https://selfscholar.files.wordpress.com/2013/03/16.pdf [17].

The 1980s-1990s: Sustained Contraction in Enrollments; Increased Total Immigration

The flow of Iranian students in the U.S. came to an abrupt end with the 1979 Islamic Revolution, when a populist backlash against rapid modernization and Westernization under the Shah swept in a conservative anti-American theocracy. The American Embassy in Tehran became a visible target for anti-Western activists, who ultimately seized the embassy and took dozens of hostages. The crisis dragged on for 444 days.

In response, the Carter administration severed diplomatic relations with Iran, ceased issuing visas to Iranians, and directed all Iranian students to report to immigration. Thousands of Iranian students left the country or were deported [2]. Across the nation, meanwhile, a number of U.S. states attempted to prohibit [18] universities from admitting Iranian students. Most of these measures were ultimately found unconstitutional and dropped, but they were indicative of the political climate and the difficulties Iranian students were facing at the time.

In Iran, the revolutionary government of the Islamic Republic put a halt to outward-looking education policies and launched a campaign to purge the nation’s education system of Western influences. The Islamization of cultural institutions involved the closure of most Iranian universities for three years, from 1980 to 1983.international hegemonic system [19].”

In the years after the revolution, the U.S. and Iran broke off diplomatic relations altogether. The decades-long wave of professionals and visiting students voluntarily seeking educational opportunities in the U.S. largely dried up, and the total number of Iranian students in the U.S. declined, reaching its lowest point, 1,660 students, in the 1998/99 academic year (IIE Open Doors Data). In these students’ place emerged a steady stream of involuntary migrants: The elites of the old regime – formerly privileged upper and middle-class families – religious minorities, and other social groups disadvantaged by the regime change in Tehran. The subsequent eight-year Iran-Iraq war led to the emigration of large numbers of young men evading the military draft [20]. the result was that, even as student numbers declined, the total number of Iranian immigrants in the U.S. rose.

The Recent Past: Increased Outbound Mobility; Iranian Governmental Ambivalence

Hostile relations between the U.S. and Iran impeded student mobility for decades after the Islamic Revolution. Academic ties and transnational partnerships were severed, and the imposition of economic sanctions, and suspension of international banking links, money transfers, and scholarships negatively affected Iranian students. However, the 2000s saw a slow but steady increase in Iranian student enrollments in the U.S., which have been growing for the past 12 consecutive years. Growth rates first started to pick up in 2010/11, when Iranian enrollments in the U.S. reached 5,626 compared to 2,216 in 2001/02. In 2015/16, 12,269 Iranian students were studying in the U.S., according to the IIE’s Open Doors data [21]. This is the largest number of Iranian students in the U.S. since 1985 and represents a 118 percent increase compared to 2010/11.

The Iranian government’s response to the increased interest of Iran’s students in U.S. education has been complex. The country’s policies are shaped by different factions, both conservative and reformist. Conservative groups continue to fear the “Westoxification [22]” of Iranian society and perceive American policies as part and parcel of a “cultural invasion.” [23] Exposure of legions of Iranian students to Western ideas is seen as threatening to the stability of the theocratic regime. Such fears were amplified by democratization movements of the Arab Spring [24], which unseated a number of governments, and by mass-scale anti-government demonstrations in Iran in 2009 and 2011. Washington’s objective of encouraging educational exchanges as a means of advancing democratization further amplified concerns. (See below.)

Some Iranian parliamentarians in recent years have threatened legislative measures to nullify academic degrees from foreign countries.espionage operations by Iranian news media [25]. At the same time, the centrist government of President Hassan Rouhani encourages openness to the outside world and foreign investment. Elected in 2013, Rouhani, who presides over a cabinet that includes, as the Atlantic [26] notes, “more … members with Ph.D. degrees from U.S. universities” than the Obama administration’s,http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2013/12/the-case-for-giving-irans-scholar-diplomats-a-chance/282010 [27], Nasseri, Ladan. Iranian Exiles Are Having Second Thoughts. Bloomberg, August 4, 2015. Accessed December 2016, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-08-05/iranians-who-left-and-never-looked-back-are-thinking-again [28]. has called upon Iran’s Western diaspora [28] to return home to assist in developing the country. Iran also explicitly views internationalization as a way to increase the quality of research and education in Iran. The government has set an official goal of establishing Iran as a knowledge-based economy by 2025. To do so, it seeks to increase scientific ties with prestigious international universities and establish transnational partnerships between Iranian and foreign universities in special economic zones.student exchange programs, particularly at the graduate level [29]. The government-funded German Academic Exchange Service in 2014 was allowed to open an office in Tehran [30].

Iran’s government has also sought to promote international student exchanges. In 2007, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis established an undergraduate student exchange program with the University of Tehran [31]. At the initiative of the Iranian government and the involved universities, this program has since been extended to the graduate level. A 2010 to 2015 five-year governmental plan set out to increase the number of foreign students in Iran to 25,000 and to establish an English-language university to attract foreign students – objectives that had not yet been achieved as of January 2017. The Iranian government also supports a number of Iranian overseas students with scholarships, and in 2005 reportedly lifted a scholarship ban for Western countries like the U.S. and the UK.[7]Ditto, Steven. 2014. Red Tape, p. 17

The U.S. View: Educational Exchanges as a Form of Soft Power

Increases in Iranian student mobility into the U.S. over the past decade stem from multiple factors. U.S. policy changes have played an explicit role in facilitating the influx of Iranian students, despite the simultaneous imposition of harsh economic sanctions. Many in foreign policy circles view international student exchange as a tool to influence the thinking of foreign elites and promote political change in sending countries. Increased student exchange with Iran was part of the Bush administration’s policy of promoting democratization and regime change abroad.

In 2006, the U.S. State Department established a program called “EducationUSA Opportunity Funds [32]” in the spirit of its so-called “transformational diplomacy [33].” The program was designed to facilitate the enrollment of foreign students at U.S. institutions by establishing advisement centers abroad to inform students on application and immigration procedures. The “EducationUSA Iran” program [34] established in 2007 – which is still active and currently administered by the Institute for International Education – did not include an overseas office in Iran, but was a substantial effort that involved, for example, the maintenance of a Persian-language website.

Like the Bush administration before it, the Obama administration increased economic sanctions on Iran. At the same time, the Obama administration went even further in trying to attract Iranian students. In 2011, the U.S. government ended the visa restrictions it had imposed on Iranian students for decades. Unlike students from most other countries, Iranian students were previously restricted to single-entry visas, forcing Iranians to reapply for new visas when leaving the country in case of a family emergency, or when attending international conferences. After 2011, Iranian students were eligible for two-year multiple-entry visas [35]. Reports from 2012 [36] indicated that large numbers of students in STEM fields were still being issued single-entry visas despite the policy change In 2014, the government also started to allow accredited U.S. universities to apply for licenses to establish student exchange agreements [37] with Iranian universities and to export services like online courses to Iran [38]. Following this policy change, online providers like Coursera [39] anticipated [40] enrolling tens of thousands of Iranian students in open online courses.

Today: Increased Tensions Affect U.S.-Bound Mobility

Prior to his election last November, U.S. President Donald Trump promised to dismantle the 2015 nuclear agreement with Iran. While the feasibility of such a change remains unclear, the likelihood of renewed bilateral hostilities is real. Within weeks after taking office, the Trump administration imposed new sanctions on Iran in response to a ballistic missile test amid hostile rhetoric towards Tehran [41]. The January 27 travel ban directly affects Iranian students [42] and raised alarm among administrators and students at institutions across the country [3]. On February 7, The New York Times described escalating criticisms of the new administration in Iran: “With Iran [43] calibrating how to deal with President Trump, its supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei [44], caustically thanked the new American leader on Tuesday for revealing “the true face” [45] of the United States.”

As of the publication of this article, the Trump administration’s travel ban on citizens of Iran and six other Muslim-majority countries was under injunction, and an appeal was working its way through the courts. As a result, the order’s ramifications for international students and others already in the country remained unclear. At the very minimum, the uncertainty will slow Iranian student arrivals and visa applications. If the injunction against the order is upheld, experts anticipate much stiffer restrictions for Iranians, including new measures, which President Trump has referred to as “extreme vetting,” that dramatically increase screening of visa applicants.

Even under the Obama administration, Iranians faced more scrutiny and tighter security clearances than nationals from other countries, and Iranian students continued to report long waiting periods for visas. Processing times in 2016 reportedly often exceeded four months and on occasion lasted more than nine months. The overall visa refusal rate for Iranians, including non-student visas, was 44 percent in 2015. Some of the visa and other hurdles these students faced even prior to Trump’s order on travel include:

- Dual-use and competitive restrictions: Provisions of a 2012 law denied education visas to Iranian nationals seeking to study specific subject areas on U.S. campuses. Included were fields like nuclear and petroleum engineering, and even business programs related to the petroleum industry. The issue came to national prominence in 2015 when the University of Massachusetts at Amherst barred Iranian students from a wide range of study programs [46], including chemical engineering and chemistry, electrical and computer engineering, mechanical engineering, microbiology, physics, and polymer engineering. In another example, Kaplan, a U.S.-based distance education provider, cited U.S. sanctions when it barred Iranian residents from enrolling in STEM courses offered in the U.K. [47] And while such claims cannot be verified independently, some U.S. universities are also said to impose such restrictions informally [48] without announcing them as official policy. The 2012 law did not place restraints on universities once the visas were issued. However, questions such as whether the transfer of certain software licenses to Iranian students might violate U.S. law are a burden to university administrators. In practice, such doubts and hesitations tend to work against the Iranian students.

- Logistical barriers: Other obstacles involve logistics and cost. For instance, the U.S. has not had a diplomatic mission in Iran since the Iranian hostage crisis of 1979 to 1981. To apply for student visas at U.S. embassies, Iranian students have had to travel abroad, often to Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, or Cyprus – a time-consuming and expensive endeavor, especially since the process sometimes required repeat visits. Moreover, standard admissions tests like the GMAT, LSAT, MCAT, or SAT are not offered in Iran; applicants have to travel abroad to sit for these exams. On average, the cost for U.S.-bound Iranian students seeking entry into the U.S. is estimated at $3,000 to $5,000 before even purchasing a plane ticket.[9] Ditto, Steven (2014). Red Tape, p.25.

- Cash-flow problems: Until 2016, Iranian students could not have international credit cards. They had to pay expensive intermediary services or use smuggled prepaid cards issued in other countries when paying for things like online application fees. The lifting of sanctions in 2016 has paved the way for partially re-integrating Iran into the international banking system. Throughout 2016, a number of Asian credit card companies were negotiating with the Iranian government for access to Iran, and at least one bank, the Korean Woori Bank, has opened an office in Iran in 2016. Iran in September 2016 also introduced its first credit card since 1979, although the Iranian card is, as of now, not accepted abroad. However, Iran is still far away from full access to the international banking system. As of 2017, the U.S. maintains a number of sanctions on Iran over the country’s human rights policies and the alleged state sponsoring of terrorism. The sanctions exclude Iran from the U.S. banking system and prevent transactions in U.S. dollars – the world’s main international business currency. The continuation of sanctions coupled with uncertainties about the future direction of U.S.-Iran policies have a chilling effect on European banks, which have so far stayed clear of the Iranian market. The banking infrastructure in Iran is outdated and many Iranian banks lack liquidity. Direct wire transfers from Iran to the U.S. remain difficult. The U.S. presently allows for personal non-commercial transactions, but these transactions are inconvenient: Transfers must be made via a third country foreign financial institution and U.S. banks may ask for proof of personal use, for example in the form of an affidavit. The long and short of it is that Iranian students still face greater logistical challenges in money-related matters than U.S.-bound students from other countries.

- Restrictions on exiting Iran: Further complicating the application and enrollment processes are restrictive exit requirements imposed by the Iranian government: Young men who have not yet served in the military have to deposit an “exit security” fee intended to assure their return, and women traveling abroad are sometimes barred from leaving the country without being permitted or accompanied by a male guardian.https://iranwire.com/en/features/1429 [49], http://www.nytimes.com/2001/01/24/news/iran-vetoes-study-abroad-for-women.html [50].

The Future: If Not the U.S., Where?

If enacted, how will the Trump administration’s January 2017 visa ban affect Iranian enrollments? Common sense provides the same answer as history and the experiences of other countries do: Growth rates will slow, and numbers will drop, if not freeze altogether.

After the 9/11 terror attacks and the subsequent adoption of tighter visa regulations, growth rates for international enrollments slowed. In 2003/04 the U.S. witnessed the first absolute decrease in international student numbers since 1971/72 [51]. The impact was not evenly distributed: IIE Open Doors data shows that student arrivals from a number of Muslim countries in the Middle East and Pakistan dropped by particularly significant margins. Patterns in international student flows in the UK and Australia also suggest a direct correlation between immigration policies and international student enrollments.http://www.independent.co.uk/student/news/government-visa-rules-are-making-britain-a-difficult-and-unattractive-study-destination-for-a6925666.html [52], Ten sure ways countries can turn away international students. The Conversation, October 31, 2015. Accessed December 2016. https://theconversation.com/ten-sure-ways-countries-can-turn-away-international-students-48419 [53], Mixed signals continue regarding the extent of Australia’s international education recovery. ICEF Monitor, July 11, 2013. Accessed December 2016, http://monitor.icef.com/2013/07/mixed-signals-continue-regarding-the-extent-of-australias-international-education-recovery [54]/, Australia reverses three-year enrolment decline, commencements up sharply in 2013, ICEF Monitor, March 25, 2014. Accessed December 2016, http://monitor.icef.com/2014/03/australia-reverses-three-year-enrolment-decline-commencements-up-sharply-in-2013 [55]/. Canada’s 2012 decision to sever diplomatic relations with Iran in response to Iran’s Syria policy has likely contributed to a decline in Iranian student enrollments in Canada. After almost doubling between 2006 and 2013, the absolute number of Iranian students in Canada declined by about 10 percent between 2013 and 2015. http://open.canada.ca/data/en/dataset/052642bb-3fd9-4828-b608-c81dff7e539c?_ga=1.129598988.1449264574.1482960422 [56]. IIE reports significantly different numbers, but also shows a slight decline between 2013 and 2015. http://www.iie.org/Services/Project-Atlas/Canada/International-Students-In-Canada#.WGQYxVMrLcs [57], See also: Canada books another strong year of international enrolment growth, ICEF Monitor, November 25, 2015. Accessed December 2016. http://monitor.icef.com/2015/11/canada-books-another-strong-year-of-international-enrolment-growth [58]/

Where will outbound Iranian students go in the coming years? Europe is one region poised to see increased Iranian enrollments. Germany, which offers high-quality graduate-level engineering programs, many in English, saw a 20 percent increase in Iranian student enrollments between 2013 and 2015.http://www.wissenschaftweltoffen.de/kompakt/wwo2014_kompakt_de.pdf [59]and http://www.wissenschaftweltoffen.de/kompakt/wwo2016_kompakt_de.pdf [60] The country historically has strong economic ties with Iran and is often named the most popular Western country in surveys of the Iranian population [61].

Italy, like Germany, is an important trading partner for Iran as well as an increasingly attractive education destination for Iranian students abroad. In 2014, it became the fourth most popular country among outbound Iranian students.http://uis.unesco.org/en/uis-student-flow [62]

Closer to home, Malaysia and Turkey have already begun to attract significant numbers of outbound Iranian students. In 2012, 8,170 Iranians comprised one of the largest groups of foreign students in Malaysia.http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0023/002354/235406e.pdf [63] Although enrollments have declined since, the country has potential for future growth, and the Iranian government currently actively encourages student exchange with Malaysia. Iranian enrollments in Turkey have also increased over the years. In 2014, Turkey was the second most popular destination country after the U.S. with 4,343 students. http://uis.unesco.org/en/uis-student-flow [62]

It is a testament to the strong motivation of Iranian students that so many have chosen to study in the U.S. in the recent past despite the tremendous difficulties that they face. They have, as a group, proven themselves remarkably adept at persevering through even the steepest immigration hurdles. But even if the courts rule that the recent travel is unconstitutional, Iranian enrollments in the U.S. may not easily rebound. As of early 2016, the end of international nuclear sanctions opened additional paths for Iranian students to pursue their academic goals in many parts of the world. Going forward, these students, like their peers in other countries, may well opt for education in countries that have not shown themselves quite so ready to close their doors with little to no warning.

References

| http://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/red-tape-iron-nerve-the-iranian-quest-for-u.s.-education [15]. | |

|---|---|

| http://www.iie.org/Research-and-Publications/Open-Doors/Data/International-Students/All-Places-of-Origin/1950-2000 [16]. Zikopoulos, Marianthi: Detailed Analysis of the Foreign Student Population, 1989-1990. Institute of International Education, New York. Accessed December 2016, https://selfscholar.files.wordpress.com/2013/03/16.pdf [17]. | |

| ↑3 | For an overview of the policies towards universities at that time see Mojab, Shahrzad. 1991. The State and University: The “Islamic Cultural Revolution” in the Institutions of Higher Education of Iran, 1980-87, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 1991. |

| ↑4 | Ditto, Steven. 2014, Red Tape, p. 16 |

| http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2013/12/the-case-for-giving-irans-scholar-diplomats-a-chance/282010 [27], Nasseri, Ladan. Iranian Exiles Are Having Second Thoughts. Bloomberg, August 4, 2015. Accessed December 2016, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-08-05/iranians-who-left-and-never-looked-back-are-thinking-again [28]. | |

| ↑6 | UNESCO: UNESCO Science Report: Towards 2030, Paris 2015, Accessed December 2016, http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0023/002354/235406e.pdf. 394 |

| ↑7 | Ditto, Steven. 2014. Red Tape, p. 17 |

| Reports from 2012 [36] indicated that large numbers of students in STEM fields were still being issued single-entry visas despite the policy change | |

| ↑9 | Ditto, Steven (2014). Red Tape, p.25. |

| https://iranwire.com/en/features/1429 [49], http://www.nytimes.com/2001/01/24/news/iran-vetoes-study-abroad-for-women.html [50]. | |

| http://www.independent.co.uk/student/news/government-visa-rules-are-making-britain-a-difficult-and-unattractive-study-destination-for-a6925666.html [52], Ten sure ways countries can turn away international students. The Conversation, October 31, 2015. Accessed December 2016. https://theconversation.com/ten-sure-ways-countries-can-turn-away-international-students-48419 [53], Mixed signals continue regarding the extent of Australia’s international education recovery. ICEF Monitor, July 11, 2013. Accessed December 2016, http://monitor.icef.com/2013/07/mixed-signals-continue-regarding-the-extent-of-australias-international-education-recovery [54]/, Australia reverses three-year enrolment decline, commencements up sharply in 2013, ICEF Monitor, March 25, 2014. Accessed December 2016, http://monitor.icef.com/2014/03/australia-reverses-three-year-enrolment-decline-commencements-up-sharply-in-2013 [55]/. | |

| http://open.canada.ca/data/en/dataset/052642bb-3fd9-4828-b608-c81dff7e539c?_ga=1.129598988.1449264574.1482960422 [56]. IIE reports significantly different numbers, but also shows a slight decline between 2013 and 2015. http://www.iie.org/Services/Project-Atlas/Canada/International-Students-In-Canada#.WGQYxVMrLcs [57], See also: Canada books another strong year of international enrolment growth, ICEF Monitor, November 25, 2015. Accessed December 2016. http://monitor.icef.com/2015/11/canada-books-another-strong-year-of-international-enrolment-growth [58]/ | |

| http://www.wissenschaftweltoffen.de/kompakt/wwo2014_kompakt_de.pdf [59]and http://www.wissenschaftweltoffen.de/kompakt/wwo2016_kompakt_de.pdf [60] | |

| http://uis.unesco.org/en/uis-student-flow [62] | |

| http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0023/002354/235406e.pdf [63] | |

| http://uis.unesco.org/en/uis-student-flow [62] |