Education in Iran

WES Staff

This education profile is based on an earlier version by Nick Clark. It has been revised as of February 2017 to reflect the most current available information

Despite the end of international nuclear sanctions in 2016, Iran’s economy remains unstable. High youth unemployment, even among college graduates, and out-migration of skilled citizens are just two of the ongoing challenges. In the higher education sector, a severe shortage of seats at the postgraduate level has served as a prompt for substantial numbers of Iranian nationals to seek education abroad. A combination of shifting demographics and a rapid massification of the country’s private higher education sector may reverse that trend in the coming years, but in the short term at least, the outbound mobility of many Iranian students is likely to remain unchecked.

In this article, we offer an overview of Iranian student mobility and Iran’s education system, and provide insight into how to evaluate common academic credentials at both the secondary and tertiary levels. Readers should note that despite recent shifts in international relations, Iran remains relatively closed to the Western world. Current information about some aspects of the country’s education system can, as a result, be difficult to obtain.

International Student Mobility

Iran’s higher education sector has undergone tremendous growth in recent years. The country has seen a rapid expansion of the private sector and is now home to two of the ten largest universities in the world. However, almost all the expansion happened at the undergraduate level. At the graduate level, there are still far too few programs to accommodate demand, a factor that drives considerable outbound mobility among Iranian students.

More than 48,000 Iranian students were studying abroad in 2014, according to figures published by the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS). The 2014 total represents a 78 percent increase over 2008 numbers, when just under 27,000 Iranian nationals were enrolled at foreign institutions of higher education.

The 2016 removal of nuclear-related UN sanctions, which has the potential to accelerate Iran’s already strong outbound international student mobility numbers, has given rise to widespread speculation that the country may become an even more substantial market for international education.

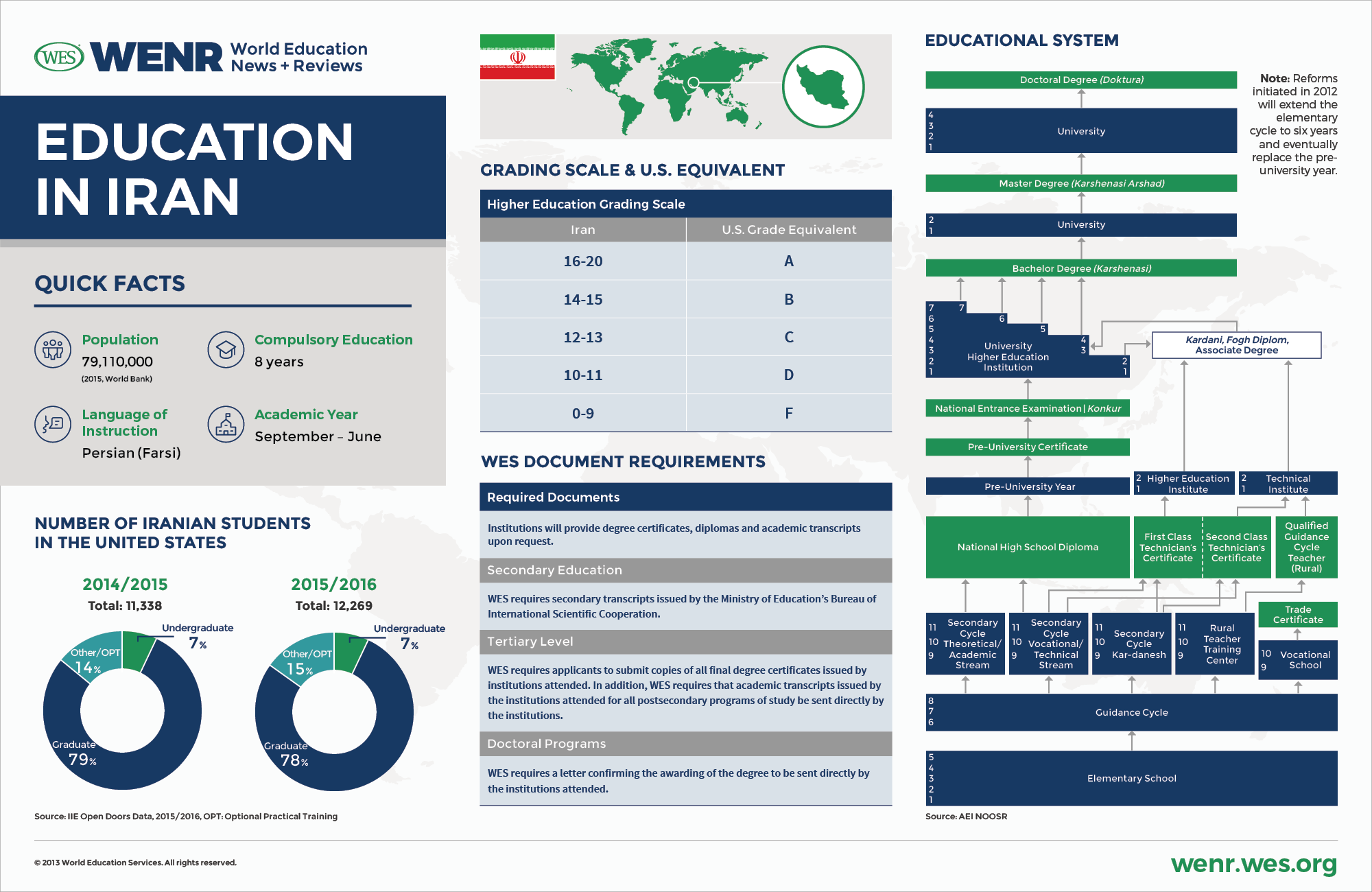

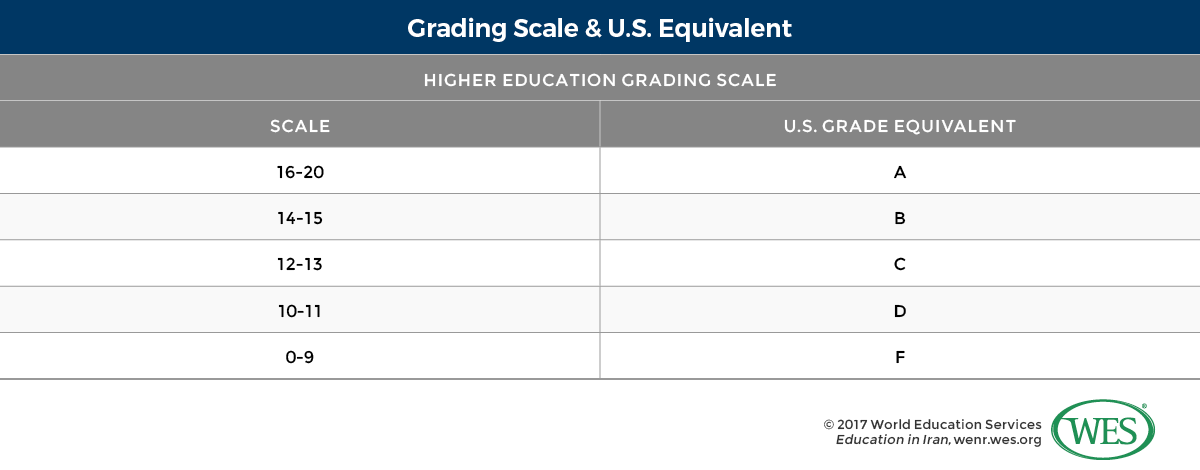

Iranian Students in the U.S.

In the United States, the number of Iranian students over the years has fluctuated from as many as 51,310 in 1979/80 (at which point Iran was the leading place of origin for international students enrolled in U.S. institutions) to as low as 1,844 in 2000/01. In the 2015/16 school year, 12,269 Iranian students were enrolled in the U.S., according to the Institute of International Education’s Open Doors report. This number represents a 118 percent increase compared to 2010/2011. The vast majority of Iranian nationals on U.S. campuses in 2015/16 – 77 percent – were enrolled at the graduate level. Most were studying in STEM fields (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics).

The rise and fall and rise of Iranian enrollments in the U.S. are a testament to the impact that geopolitical factors and diplomatic relationships have on Iranian student mobility trends. While recent years have seen a resurgence in numbers, immigration policies under the new administration, are likely to deter additional enrollments in the near-term future. (For the history and future prospects of Iranian students in the U.S. see our in-depth analysis in this month’s issue of WENR).

The Education System of Iran

Administration

Iran is a theocracy based on Islamist ideology: the central government exerts strong control over education.

The central government is responsible for the financing and administration of elementary and secondary education through the Ministry of Education, which supervises national examinations, monitors standards, organizes teacher training, develops curricula and educational materials, and builds and maintains schools. Education policies are approved and overseen by a number of bodies including Iran’s parliament and the cabinet of ministers. The Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution, a body appointed by and reporting to Iran’s Supreme Leader, is the highest authority in educational affairs and wields far-reaching control over policies and regulations.

At the local level, education is supervised through the provincial authorities and the district offices.

Funding

According to UNESCO statistics published by the World Bank, Iran in 2014 spent 2.95 percent of its GDP on education at all levels. This number represents 19.7 percent of all government expenditures—a relatively high percentage by international comparison. Globally, governments spent an average of 14.25 percent of total expenditures on education in 2012.

Literacy and Enrollment Rates

Iran has a high literacy rate by regional standards, and in comparison to many other countries at similar levels of development, is a very educated society. The country’s adult literacy rate stood at 84.6 percent in 2013 (UNESCO), compared to 85 percent worldwide and 78 percent in the neighboring Arab states [1] UNESCO Institute for Statistics. 2015. Adult and Youth Literacy. http://www.uis.unesco.org/literacy/Documents/fs32-2015-literacy.pdf. Accessed December 2016.. The literacy rate among 15-24 year-olds is even higher at 98 percent (2015).

The net enrollment rate at the elementary level (percentage of pupils in official school age group) was again high by regional standards: 99.1 percent in 2015. The completion rate to the end of elementary education was 97.53 percent in 2014 (percentage of relevant age group finishing grade 5). According to UNESCO, the gross enrollment rate at the secondary level (percentage of all students including older students) was 89.17 percent in 2015. The gross secondary enrollment rate in neighboring Pakistan, by comparison, was 44.53 percent in 2015.

Basic Education (Dabestan and doreh-e rahnama-ii)

Basic education lasts until grade 9 and is compulsory, and in the public school system, free.

Prior to 2012, the basic education cycle lasted eight years and was divided into a five-year elementary education cycle (dabestan) and a three-year lower secondary, or guidance, cycle (doreh-e rahnama-ii). Reforms adopted in 2012 have since then extended the elementary cycle to six years, lengthening basic education to a total of nine years, although most students presently still study under the old structure.

During elementary school, students attend 24 hours of class per week. The curriculum covers Islamic studies, Persian studies (reading, writing, and comprehension), social studies, mathematics, and science.

At the lower secondary or guidance level, subjects like history, vocational studies, Arabic, and foreign languages are introduced, and students attend more hours of class each week. The curriculum at this level is national and consistent across all schools.

Examinations

Students take exit examinations at the end of grades 6 and 9 (grades 5 and 8 in the old system). Assessment at the end of the lower secondary cycle is designed to determine students’ preparation for and placement in one of three streams at the upper-secondary level: academic, technical, or vocational. Students who fail have to repeat the year and may take the examination again the following year. If students fail a second time, they must either undertake basic vocational training or seek employment. The examinations are held in June at the end of each academic year and they are conducted by provincial education authorities. Successful students are awarded a Certificate of General Education.

Depending on grades achieved in the relevant subjects at the end of the guidance cycle, students are eligible to continue their education in the academic or vocational/technical branches of the secondary cycle.

Upper Secondary (Dabirestan)

Upper secondary education is presently three years in length, lasting from grade 9 to grade 11 (or grade 10 to 12 in the new system). Upper secondary education is not compulsory, although it is available for free at public schools. At this level, students are segmented into three fields (or streams) of the education system: academic (Nazari), technical (Fani Herfei), and vocational/skills (Kar-danesh). A student’s stream is dependent primarily on his or her examination results at the end of the lower secondary cycle, and to a lesser extent on student preference. The academic stream has traditionally been the most popular.

The Academic and Technical Streams

During the first two years, students in the academic and technical stream follow a common curriculum (although load varies slightly by branch) with the third year focusing on a specialized curriculum.

- Students in the academic stream study one of four subject areas in their final year: humanities and literature, mathematics and physics, experimental sciences, or Islamic theology. (There was previously a fifth specialty focused on socio-economic issues.)

- Students in the technical stream follow one of three specializations: Technical (industry), business and vocational (service industry), or agriculture. Sub-specializations include fields such as woodworking/carpentry, auto mechanics, building and construction, food industries, health services, and tailoring.

Students from the academic and technical streams are awarded the Diplom-Motevaseteh (certificate of completion of secondary school studies) upon successful completion of studies and after passing the national examination. Graduates either continue on to a final pre-university year of education or opt to enter the workforce.

The Vocational Stream

The skills or vocational stream is more practice-oriented and leads to the award of a skills certificate (Diplome Kardanesh) in the trade/profession studied. Training for skilled or and semi-skilled employment is provided in 400 areas of specialization. Some vocational students at this level enroll in five-year integrated associate diploma programs at technical institutes. The degree awarded at the end of the five-year stream is the Kardani or Fogh Diplom.

Pre-University Year (Pish-Daneshgahi)

The pre-university year is a preparatory year for students who plan to take Iran’s standardized university entrance examinations, the Konkur (or Concours), required for admission into most university programs. The pre-university year originally evolved prior to 2012, and will eventually be incorporated into the new 12-year 6+3+3 system, so that graduates can sit for entrance examinations without first completing an additional year of pre-university study. For now, however, the additional year is still a requirement for anyone who wants to sit for the Konkur.

During the pre-university year, students specialize in a specific field of study (math, experimental sciences, humanities, art, or Islamic culture). Students are taught at pre-university centers administered by the Ministry of Education. They are graded by continuous assessment and by final examination (accounting for 75 percent of the overall grade.) Successful students are awarded the Pre-University Certificate and entitled to sit for the Konkur for university admission.

The Konkur: Iran’s Standardized Admissions Examination

Entry to Iran’s tuition-free public universities is based on the very competitive University Entrance Examination known as the Konkur or Concours. Many private universities also use this examination for admission purposes. One notable exception is the semi-private Islamic Azad University (IAU), the country’s largest university. IAU administers its own entrance exam, which is very similar to the Konkur. The university, which charges tuition fees and enrolls over 1.7 million students at campuses around the country, is not nearly as competitive to get into as public universities.

Students sitting for the Konkur exam.[2]Iran Wire https://iranwire.com/en/features/1395

Associate degree programs do not require the Konkur examination for admission, although some administer a separate entrance examination. There is a separate Konkur examination for entry into graduate programs.

Higher Education

Higher education is offered at the following types of institutions:

- Universities

- General/Comprehensive

- Specialized (fine arts, engineering, medicine)

- Comprehensive Technology (applied sciences)

- Payam-e Noor University (distance learning)

- Medical

- Private

- Teacher Training Colleges

- Technical Institutes and Higher Education Institutes (non-university)

All institutions of higher education, except medical institutions, are under the supervision of the Ministry of Science, Research and Technology. Medical universities are supervised by the Ministry of Health, Treatment and Medical Education. Post-secondary vocational education is overseen by the Technical and Vocational Training Organization. All programs at private universities must be approved by the Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution and recognized by the Ministry of Science, Research and Technology. Quality assurance of higher education institutions comes under the auspices of the Ministry of Science, Research and Technology. Concrete information on the process and methods of assessment is not available.

Universities: Past and Present

After the Islamic revolution of 1979, the government closed almost all universities in Iran. Closures lasted from 1980 and 1983, during which time the curriculum was revised. Meanwhile, the university system was nationalized and desecularized. The Islamist government held an unfavorable view of private education and did not allow private institutions to operate for nearly ten years after the revolution (with the notable exception of Islamic Azad University).[3]Arabi, Andas Mdandar. 2014. Privatization of Education in the Islamic Republic of Iran: One step forward, one step back. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/2331186X.2015.1029709. Accessed December 2016.

Today Iran’s university system includes both public and private universities. Universities are composed of largely autonomous faculties (daneshkadeh). The vast majority of programs at private institutions are at the undergraduate level, and Iran currently faces a shortage of educational opportunities at the graduate level, a factor that has contributed to the out-migration of academic elites. Only six percent of approximately 900,000 applicants to master’s degree programs and four percent of 127,000 doctoral applicants reportedly secured a spot in 2011.[4] Malekzadeh, Shervin. 2015. The new business of education in Iran. Washington Post. 19 August. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2015/08/19/the-new-business-of-education-in-iran/?utm_term=.02c9b04d90ca. Accessed December 2016

Public Higher Education in Iran

Iran’s public universities have a relatively good reputation, particularly for undergraduate education in engineering. The University of Tehran is ranked by the Academic Ranking of World Universities as one of the top 400 universities in the world (301 – 400). Amirkabir University of Technology is listed among the top 500 universities in the same ranking (401 – 500). Sharif University of Technology has appeared on the list in previous years and is presently ranked by Times Higher Education among the top 600 universities in the world (501 – 600).

Iran’s public universities have a relatively good reputation, particularly for undergraduate education in engineering. The University of Tehran is ranked by the Academic Ranking of World Universities as one of the top 400 universities in the world (301 – 400). Amirkabir University of Technology is listed among the top 500 universities in the same ranking (401 – 500). Sharif University of Technology has appeared on the list in previous years and is presently ranked by Times Higher Education among the top 600 universities in the world (501 – 600).

In the past, Iran’s higher education sector had far too few seats to fill demand, with admission rates at public universities as low as 12 percent within the last decade. Entry into public institutions remains competitive, although the worst of the capacity crisis has been addressed by the rapid massification of Iran’s private higher education sector. In 2013, 57.9 percent of the 921,386 students taking the Konkur exam were admitted to public universities.

Entry into STEM programs remains especially competitive.

Private Higher Education in Iran

By the end of the 1980s, an exploding youth demographic led Iran’s government to reassess its prohibition on private universities, and in 1988, it permitted non-profit private universities to apply for charters to operate.

The number of private higher education institutions in Iran has increased drastically since then. Iran’s Ministry of Higher Education and Research presently lists 51 public universities on its website. In 1977, by comparison, Iran had only 16 universities with a reported number of 154,315 students. The Ministry’s website does not provide information on the number of institutions in the dynamic private sector, but some reports suggest a rapid increase from 50 private HEIs in 2005 to 354 in 2014, an increase of more than 600 percent in less than 10 years. The overwhelming majority of Iran’s students are enrolled in the private sector. More than one-third of all Iranian students attend the semi-private Islamic Azad University (IAU), Iran’s largest university and simultaneously one of the largest mega universities in the world with 1.7 million students.

Nurtured by former Iranian president Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, IAU was established in 1984 as the first non-governmental higher education institution to address the unmet and escalating demand for higher education. “Azad” means free in Persian and refers to the fact that the university provides “open access” compared to the highly competitive public universities. Admission to IAU is much easier than gaining entry to Iran’s public universities. IAU charges high tuition fees. Despite this funding structure, the university is, however, not a purely private institution. The government maintains oversight on degree programs and controls important aspects of university administration.

Over the past three decades, IAU has grown to become a higher education empire spanning 400 campuses across Iran and overseas campuses in the United Kingdom, the United Arab Emirates, Lebanon, and Afghanistan. Other prominent private universities include Shahrood University of Medical Sciences and Qom University.

As in other developing countries that have undergone a similar process of massification, this mushrooming of private providers is accompanied by concerns about educational quality and reports of shortcomings in facilities and the qualifications and training of teaching staff.

Technical Institutes and Higher Education Institutes

Iran’s higher education system includes multiple types of post-secondary educational options in addition to universities. Technical Institutes and regional centers for vocational education are two. Iran’s Technical and Vocational Training Organization (TVTO) under the Ministry of Cooperatives, Labor and Social Welfare, supervises some 6oo of these institutions, according to the institution’s website. Post-secondary training is also provided by licensed private training providers and technical institutes affiliated to Iran’s public Technical and Vocational University and the University of Applied Sciences and Technology. These technical institutes offer non-formal short-term vocational training programs, as well as associate-level qualifications.

Another group of non-university institutions, Iran’s so-called “higher education institutes,” were mostly upgraded to universities in the 1980s and 1990s.

Undergraduate Degrees and Qualifications

Associate Degree (Kardani – formerly Fogh Diplom)

Kardani programs are presently offered as either five-year integrated secondary and tertiary programs or as two- to three-year post-secondary qualifications. Kardani programs entail the completion of 72 to 78 credits for graduation, with one credit being equal to a 45- or 50-minute class over one semester.

Kardani degrees are awarded by universities, higher education institutes, and technical institutes. Kardani degree-holders have the option to complete a Karshenasi degree (the equivalent of a bachelor’s degree in the U.S.) in two years. (Additional detail below.)

Entry to integrated Kardani programs is based on the successful completion of basic education at grade 8 (grade 9 under the new system). The program consists of three years of secondary education in the vocational/technical stream, followed by two years at a college or institute of higher education. Students who complete the first three years of the program and choose not to continue graduate with a technical high school diploma. Those who complete the five-year program can, if they choose, obtain advanced standing into a bachelor’s degree program at a university of technology (typically the third year).

Entry into Kardani programs from secondary school is based on the completion of upper secondary education (grade 11) and, in some instances, passing an entrance examination. Completion of the pre-university year is not required.

Bachelor (Karshenasi)

The Karshenasi degree is structurally similar to a U.S. bachelor’s degree. Previously known as the Licence, the Karshenasi requires at least 130 credits at a university or other institution of higher education, and a minimum of four years of full-time study. Students must achieve a minimum grade point average of 12 out of 20 to earn the degree.

Undergraduate curricula offer a wide range of general education and elective subjects along with the degree specialization, which typically is concentrated in the last two years of the program.

Karshenasi programs are also offered as short two-year programs on top of a Kardani degree. These programs are known as Karshenasi Napayvasteh (non-continuous degree) and offer holders of Kardani degrees the option to continue their education and complete a Karshenasi degree in two years.

Master’s Degrees (Karshenasi Arshad)

Following the Karshenasi, the Iranian system has a postgraduate Karshenasi Arshad degree (previously known as Fogh Licence or Fogh Lisans). The award of the credential typically requires 28 to 45 credits, depending on the program, with an overall GPA of 14 out of 20 or better, and the completion of a thesis.

Programs are generally two years in length. These postgraduate degrees are referred to as “non-continuous master degrees” (Karshenasi-Arshad Napayvasteh) as opposed to “continuous master degrees” (Karshenasi-Arshad Payvesteh) found in the professions. (Additional detail below.)

In recent years, there has also been an increase in Western-style Master of Business Administration and Doctor of Business Administration programs offered by both public and private universities in Iran.

Of note for credential evaluators is the fact that private sector programs may at times be of questionable quality and often exempt students from academic course work on the basis of practical work experience.

Doctor of Philosophy (Doktura)

Doctoral degrees require the completion of 12 to 30 credits of coursework, a comprehensive examination, publication and defense of a research dissertation, and an overall coursework GPA of 14 out of 20 for the award of the degree. Program duration is between three and six years.

Professional Degrees (Doktura or Karshenasi-Arshad Payvesteh)

Professional degree programs in Iran are long, “continuous” programs that students enter after completion of a pre-university year. Admission to professional programs in Iran is extremely competitive and requires high scores in the national Konkur exam.

Professional degree programs are of variable lengths, depending on the field of study. Professional degree programs in dentistry, pharmacy, and veterinary medicine require six years of full-time study. Medical degrees require seven years. Most programs lead to the award of a “Doktura” (doctor) degree in the relevant profession. Degree programs require between 190 and 290 credits, as well as clinical internships, and a thesis, depending on the profession.

The Karshenasi-Arshad Payvesteh is a unified degree that is structurally similar to professional Doktura programs. It is awarded to graduates who enter professions such as architecture.

Teacher Education

Teacher education in Iran is conducted at public institutions exclusively. Teacher Training Centers are responsible for training teachers for elementary and lower secondary (guidance) schools. These centers offer two-year programs leading to a Kardani degree.

In order to teach at the upper secondary level, instructors must have a Karshenasi degree. Teachers at the upper secondary level are trained in universities and teacher-training colleges.

Only one university, the University of Tarbiat Modarres, is dedicated to the graduate-level training of university instructors. Ranked the second-best university in Iran by the Ministry of Education, the university awards master’s and doctoral degrees.

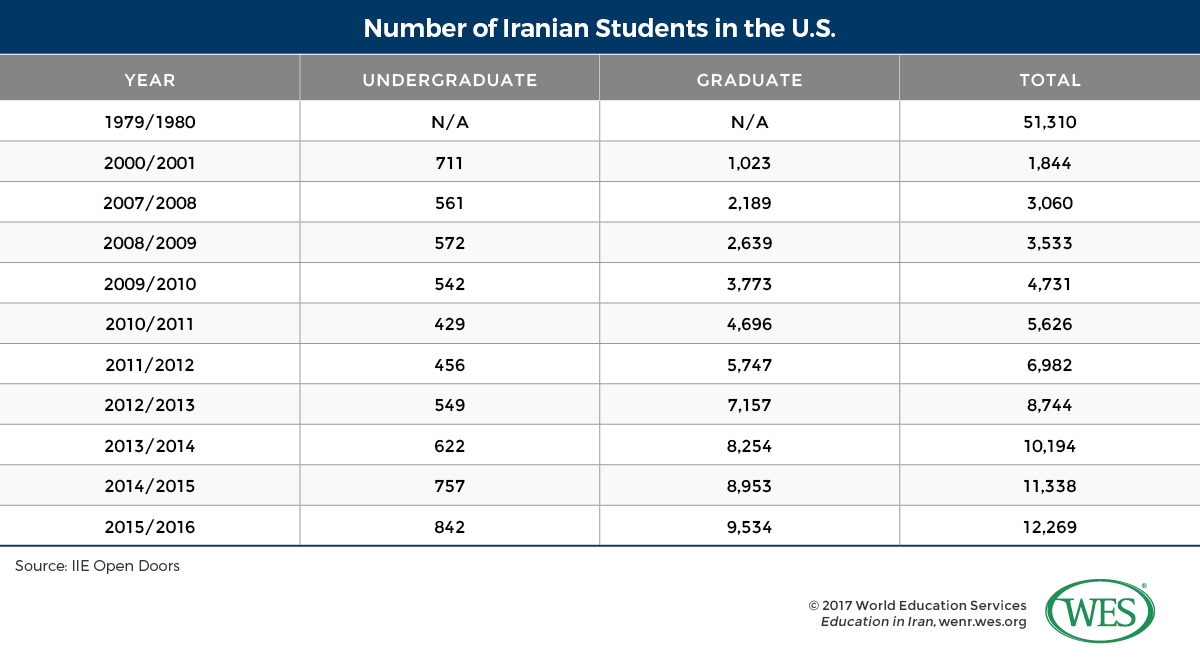

Assessment and Grading

A 0 to 20 scale is used at all levels of education throughout the country. Students at the higher education level are assessed by examination at the end of each semester. The minimum passing grade for undergraduate courses is 10, for graduate courses 12, and for doctoral coursework 14; however, overall GPAs of 12, 14, and 14 are required for the award of the respective degrees.

WES suggests the following grading equivalencies for higher education:

WES Document Requirements

Iranian institutions will provide degree certificates, diplomas, and academic transcripts upon request.

At the secondary level, WES requires photocopies of the graduation certificate and secondary transcripts issued and sent directly to WES by the Ministry of Education.

At the tertiary level, WES requires applicants to submit copies of all final degree certificates issued by the institutions attended. In addition, WES requires that academic transcripts for all post-secondary programs of study be sent directly by the institutions attended.

For completed doctoral programs, WES requires a letter confirming the awarding of the degree to be sent directly by the institutions attended.

A number of universities issue documents in English: Sharif University of Technology, Shiraz University, Tehran University, Isfahan University, Tabriz University, and Amir Kabir University. Engineering programs at several universities also issue documents in English.

English translations are usually authorized by the Ministry of Justice of the Islamic Republic of Iran and sealed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Registration and Personal Status Department. However, authorized translations do not provide confirmation of the authenticity of academic credentials.

Sample Documents

Click here for a PDF file of the academic documents referred to below:

- Secondary School Course Completion Certificate (with translation)

- Secondary School Transcript (with translation)

- Certificate of Completion of Pre-University Studies (with translation)

- Academic Transcript of Pre –University Studies (with translation)

- Kardani (Associate degree) – Degree Certificate (with translation)

- Kardani (Associate degree) – Academic Transcript (with translation)

- Karshenasi (Bachelor’s degree) from Amirkabir University of Technology – Degree Certificate (with translation)

- Karshenasi (Bachelor’s degree) from Amirkabir University of Technology – Academic Transcript (issued in English)

- Karshenasi (Bachelor’s degree) from Islamic Azad University – Degree Certificate (with translation)

- Karshenasi (Bachelor’s degree) from Islamic Azad University – Academic Transcript (with translation)

- Karshenasi Arshad (Master’s degree) – Degree Certificate (issued in Persian and English)

- Karshenasi Arshad (Master’s degree) – Academic Transcript (issued in English)

- Doktura (Doctoral degree) – Degree Certificate (with translation)

- Doktura (Doctoral degree) – Academic Transcript (with translation)

References

| ↑1 | UNESCO Institute for Statistics. 2015. Adult and Youth Literacy. http://www.uis.unesco.org/literacy/Documents/fs32-2015-literacy.pdf. Accessed December 2016. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Iran Wire https://iranwire.com/en/features/1395 |

| ↑3 | Arabi, Andas Mdandar. 2014. Privatization of Education in the Islamic Republic of Iran: One step forward, one step back. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/2331186X.2015.1029709. Accessed December 2016. |

| ↑4 | Malekzadeh, Shervin. 2015. The new business of education in Iran. Washington Post. 19 August. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2015/08/19/the-new-business-of-education-in-iran/?utm_term=.02c9b04d90ca. Accessed December 2016 |