Students From the Middle East and North Africa: Motivations, On-Campus Experiences, and Areas of Need

Megha Roy, Research Associate and Ning Luo, Research Assistant

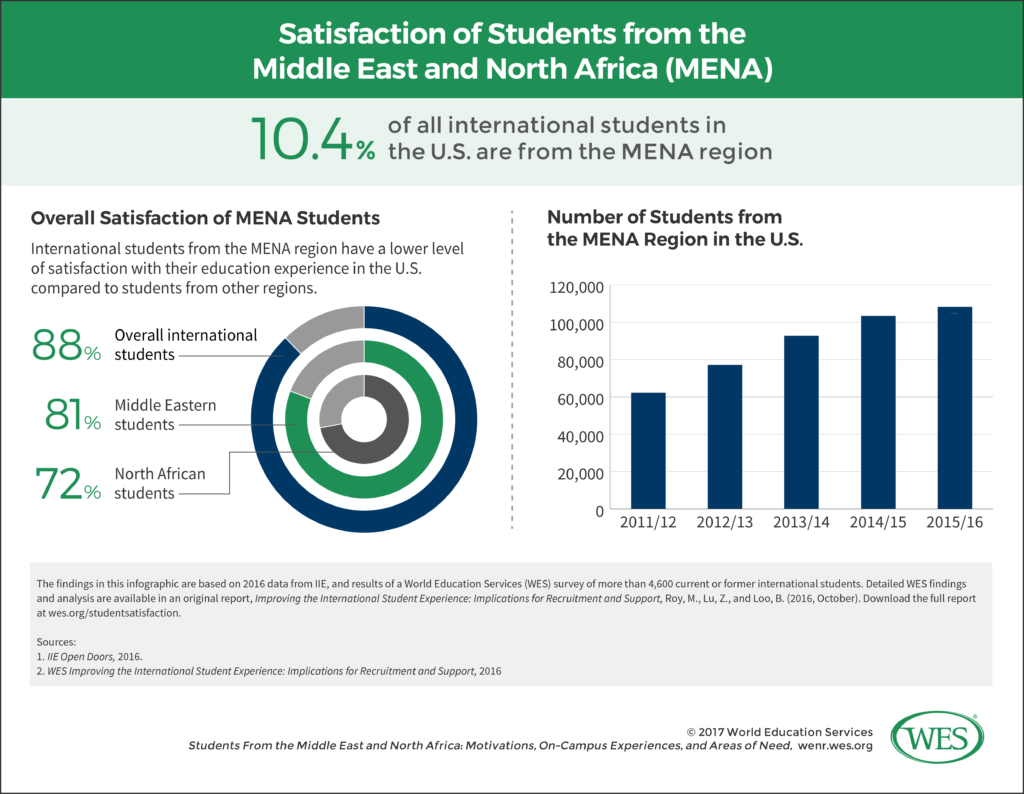

The most recent figures from the Institute of International Education (IIE) Open Doors Report indicate that in 2014/2015, 10.4 percent of all international students in the U.S. were from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). This translates to some 108,227 individual students. As a region, the MENA region is second only to Asia as a contributor of students to U.S.-based institutions.

Editor’s note: The research on which this article is based predated the January 27 executive order barring citizens of Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen from entering the U.S., and the subsequent legal arguments over the order. The recommendations included do not, therefore, provide insights into ways to protect students affected by the order, or to provide them with the resources and supports needed to navigate the situation. The steps that many institutions have already undertaken on this front provide an invaluable model for others in the field, and are critical both to ensuring affected students’ well-being, and to reassuring the global academic community that U.S. institutions maintain the long-standing tradition of academic freedom and support for students from all parts of the world.

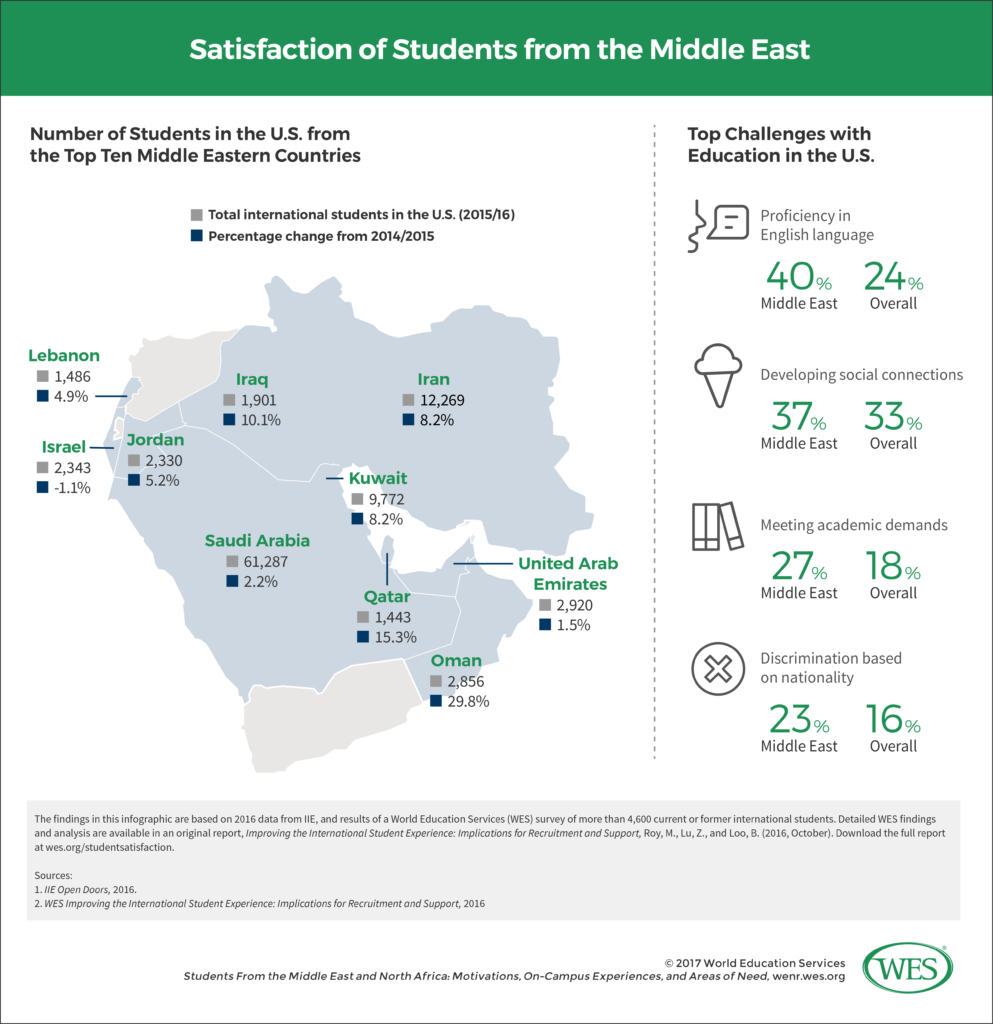

However, in terms of U.S.-bound student mobility, the signals coming from the region have recently been mixed. Even as overall numbers of students coming to the U.S. from key MENA countries have expanded in the last five years, the growth as a percentage of overall international student flow to the U.S. has shrunk (see figure). There are reasons to expect that growth rates may contract even more. Chief among them is a January 27 executive order barring citizens of seven majority-Muslim countries, including students, from entering the country. But the signs of potential weakness pre-date the January order. Declines in oil prices roiled the region throughout 2016, leading to predictions of a potential drop off in enrollments from top OPEC-dependent countries around the globe.[i] Saudi Arabia is a case in point.

In response to oil-related budget woes, the government early last year imposed new restrictions on the King Abdullah Scholarship Program, the scholarship initiative responsible for sending large numbers of Saudi students to the U.S. since 2005. Since then, the numbers of Saudi students headed to the U.S. have markedly slowed. Some schools have seen a precipitous drop in enrollments , and according to IIE, “2015/16 marked the first time since 2004/05 that Saudi students did not experience double-digit growth.” In fact, growth of Saudi student numbers in 2015/2016 plummeted to just 2.2 percent year over year, down from 11.2 percent, 21 percent, and 30.5 percent in the three preceding school years.

International Student Experience: A Top Priority Now, and Later

In a tumultuous environment, colleges and universities must focus on the long view: Politics and policies change. Borders open and close, and then open again. In the interim, institutions must ensure they are serving international student needs as effectively possible. At the present moment in history, students affected by the recent travel ban need specialized advice about the dynamic policy environment. They also need explicit statements of support, and access to counselling to help them navigate new and uncertain visa situation. But more a comprehensive approach to ensuring their well-being depends on understanding underlying motivations and long-term needs as well. The most effective long-term responses depend on deep insight into why students from particular regions come to the U.S. at all, and, most pertinently, on what those students’ experiences are once they are here.

A WES research report published last fall, “Improving the International Student Experience: Implications for Recruitment and Support,” sought to provide insights into the experiences of students from around the world. This article dives deeper into the data generated by respondents from the MENA region[1]Saudi Arabia, Iran, Israel and Jordan are discussed because they were the most represented Middle Eastern countries in the WES survey.. It details responses of international students from four key countries in the Middle East: These include Iran, Israel, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia.[2]So far, this predication has not panned out in the U.S. Between 2014/15 and 2015/16, overall student numbers have been growing quite strongly in all OPEC countries except for Libya. There has been strong growth in big countries like Nigeria (+12.4%). Algeria (+9.1%) or Iran (+8.8%). Qatar grew by 15.3%. This may change well in 2017, but the latest U.S. data we have reports growth. Growth rates have slowed in most countries, but increased in some (Qatar, Algeria). It also details responses from students in North Africa, seeking to tease out some difference between the needs and experiences of North African students as compared to the Middle Eastern students with whom so much research often lumps them.

Understanding the differences of students according to country of origin, and addressing their specific needs, starts with research-based insights. Why do students from these different countries come to the U.S. (or conversely, why do they stay away), and what do they need once they arrive? These were some of the questions we set out to answer.

Student Experience: Original Research into International Students’ Needs and Expectations

Last fall, WES published a research report entitled “Improving the International Student Experience: Implications for Recruitment and Support.” The report analyzed the responses of more than 4,600 international students (most of whom had opted to studied in the U.S.), exploring their motivations for selecting the U.S. as a study destination and then examining their experiences once on campus. The original report detailed differences by country or region of origin. At the broadest level, we found that, in comparison to students from other countries and regions, students from the Middle East and North Africa region are relatively unsatisfied with key campus support services, and have distinct needs and expectations that colleges and universities can begin to address with a few concrete actions.

Download the full report at wes.org\studentsatisfaction.

Motivators: Educational Opportunities, Language Skills, and Career Prospects

One key push factor is the perceived lack of high quality educational opportunities at home; another motivator is belief that study in the U.S. provides the chance to improve career prospects, whether back home or in the United States, after graduation. Key challenges for students from the MENA region revolve around finances, language, research opportunities, and social connection. Just over half (51 percent) of all Middle Eastern students who responded to our survey indicated that, like the majority of their peers from around the world, what most motivated them to study abroad was “better education provided outside of their home country.” Students from Jordan (65 percent) and Iran (62 percent) prioritized quality education by especially high percentages. A large proportion (44 percent) of students from the Middle East also cited “opportunity to improve career prospects in their home country” as the second most important factor in deciding to study abroad. Forty-six percent of students from Saudi Arabia cited improved career prospects back home as a significant motivator – perhaps unsurprising given the number who, prior to last year’s new restriction, studied in the U.S. courtesy of the government-sponsored King Abdullah Scholarship Program. (The program carries a heavy expectation that students return home to work after graduation.)

English-language skills are another key motivator for Middle Eastern students who study in the U.S. Twenty-eight percent cited it as the most important decision-making factor, compared to 14 percent of international students overall. The percentage was highest for students from Saudi Arabia (36 percent) followed by Jordan (30 percent).

Students from most Middle Eastern countries were less likely than their peers from other countries to cited the opportunity “to gain work experience outside of home country” as a primary motivation for coming to the U.S. Overall, only 25 percent of Middle Eastern students cited professional experience abroad as a top decision making factor. Two groups of students were notable outliers: 43 percent of Israeli students and 32 percent of Iranian students cited work experience abroad as a primary motivation for enrolling in a foreign institution. Israeli students were also relatively more motivated to study abroad as a “[pathway] to immigrate in the future” with 13 percent citing this as their most significant motivation for studying abroad, as compared to 7 percent of Middle Eastern respondents overall.

Iranian students enrolled in the U.S. may well be driven abroad by a high unemployment rate and income gap at home. However, once enrolled in U.S. institutions, they reported the highest dissatisfaction for institutional career support services – such as help finding on-campus, post-graduation jobs, along with help preparing students for career advancement – among either their Middle Eastern or global peers. (Respondents’ input on career services broke down as follows: 14 percent average dissatisfaction among Iranian students versus 8 percent among students at an aggregate, global level and 11 percent among Middle Eastern students at an aggregate level.)

Note: As of the 2015/16 academic year, Iranian enrollments in U.S. institutions were on an upswing in U.S. institutions; they rose 8.2 percent between 2014/15 and 2015/16, and 76 percent in the last five years. The recently imposed entry ban targets Iranians for exclusion, so numbers are likely to tumble in the near term future. (See “Educating Iran: Demographis, Massification and Missed Opportunities” in this month’s issue of WENR for additional detail about underemployment challenges among university-age, highly educated youth in Iran.)

Key Challenges for Middle Eastern Students: Financial, Linguistic, Academic, Social

Middle Eastern students at the tertiary-level are, by and large, satisfied with their academic experiences in the U.S. However, there are some dimensions of their experiences that demand attention. These include:

Financial Considerations

Seventeen percent of students from Middle East cited “financial aid provided by government and/or employer” as one of the biggest motivation to study abroad and this holds especially true for Saudi students (26 percent). On the other hand, 19 percent of Middle Eastern respondents to our survey said they were dissatisfied with the “availability of financial aid and/or scholarships” provided by institutions – on the face of it, this finding is somewhat surprising given the substantial government backing that some Middle Eastern countries, including Saudi Arabia, Iraq, and Kuwait, provide students studying abroad.

However, a deeper dive provides additional insight: The dissatisfaction rates were highest among students from Iran and Israel (36 percent and 26 percent respectively), countries that offer relatively little in the way of funding for studying abroad when compared to the large public scholarship program provided by the government of Saudi Arabia, for example. Funding for students from both countries is often either self-pay or family-backed. The government of Israel does not finance any study-abroad, programs, while the government of Iran funds just a few study-abroad scholarships.

The majority of students from Israel and Iran reported their biggest challenges as the cost of tuition fees (74 percent and 62 percent respectively, versus 41 percent of students from the Middle East overall). (See sidebar, “Middle Eastern Students at the Master’s Level,” for more detail on financial concerns among this population.) Financial aid packages and work-study programs may be important incentives for colleges and universities to put in place in order to attract and retain these students.

Language Skills and Academic Demands

Saudi students in particular reported that English language proficiency is a substantial challenge: 44 percent reported that they struggled with language skills – slightly higher than Middle Eastern students overall (40 percent). Saudi students also seem to struggle more intensively to meet academic demands than their Middle Eastern peers, with 37 percent reporting this as one of the biggest challenges versus 27 percent of Middle Easterners overall. This high need to improve English language skills, may account for the fact that Saudi students indicated the highest levels of dissatisfaction with institutions’ English language offerings – 18 percent dissatisfaction, much higher than the 6 percent rating among Middle Eastern students overall.

Research Opportunities

Students from Iran selected the “availability of research opportunities” as the second most important factor in their decision making about enrolling in a U.S. institution rather than an institution elsewhere in the world. According to IIE, some 78 percent of Iranian students studying in the US are at the graduate level, the highest proportion of any country sending students to the United States. This high percentage helps to explain why such a large number of Iranian students, many of whom are at the doctoral level, view research opportunities as a key factor when deciding whether to enroll at a U.S. institution. However, there’s a disconnect between students’ desire for good research opportunities and the availability on campus: By a factor of two to one, Iranian students are less satisfied with the research opportunities available to them than almost all their peers: 18 percent of Iranians were dissatisfied, compared to 9 percent of international students overall.

Loneliness and Social Connection

When we looked at the biggest challenges that students from the Middle East face with their experiences in the U.S. one of the most revealing insights was that, in comparison to international students from most other countries or regions, they struggle more in dealing with personal aspects such as loneliness/ homesickness (36 percent versus 32 percent overall international students) or discrimination based on nationality (23 percent versus 16 percent overall). Surprisingly, racial discrimination and stereotypes were considered much bigger challenge for students from the Middle East than for North African students (23 percent versus 11 percent). These challenges coupled with their lack of proficiency with English language and cultural differences, may mean they also often struggle more in developing social connections with students from other cultures (37 percent versus 33 percent overall). With more Middle Eastern students coming to U.S. campuses, international student offices should help these students adapt to U.S. campus culture and help them meet their academic needs.

Support Services

Middle Eastern students reported high levels of dissatisfaction with campus support services, such as international student orientation programs and institutions’ International Student Support (ISS) offices. Students from Iran reported the highest dissatisfaction with ISS services (23 percent versus 17 percent of Middle Eastern respondents overall). Students from Jordan reported having the highest dissatisfaction with “international student orientation programs” (26 percent versus 15 percent of Middle Eastern respondents overall). Middle Eastern students have also reported higher dissatisfaction for academic advising and student counselling services (14 and 15 percent respectively versus 9 percent overall).

Middle Eastern Students at the Master’s Level

In 2015, WES research into international master’s students in the U.S. included the following insights about Middle Eastern master’s-level students:*

- Overall, prospective Middle Eastern students are heavily concentrated in student segments with high financial resources; however, there are major differences in financial resources. Fifty-seven percent of students who fall into what WES has called “highfliers” – students with both high academic preparedness and substantial financial resources – have a budget of over $50,000 per year, compared to 16 percent of “strivers” – students with high academic preparedness and limited financial resources.

- Middle Eastern M.A.-level students are often less academically prepared than their global peers. Only 38 percent of Middle Eastern master’s students consider their academic ability to be higher than their peers, implying a lack of confidence in their academic preparedness for entering a U.S. institution. This is most likely due to a lack of English language preparedness, especially for students from Saudi Arabia and Kuwait.

- Middle Eastern students place the highest value on an institution’s location compared to other countries and regions.

- Having a strong support network nearby is important. Being close to friends or family that lives in the U.S. is more important to Middle Eastern students than other countries and regions. Overall, 17 percent of students from the region consider this sub criterion as “very important.”

- Cost of living matters: Despite the fact that many students from the Middle East rate other measures related to cost low in terms of importance to the application process, 36 percent of them described cost of living as “very important.” This is likely because many of them have their tuition fully covered by government scholarship such as KASP, while cost of living is not.

*Note: These findings were first reported by Lu, Z. and Schulmann, P. (2015, October) “How Master’s Students Choose Institutions. Research on International Student Segmentation”. World Education Services, New York.

North African Students: A Distinct Campus Experience

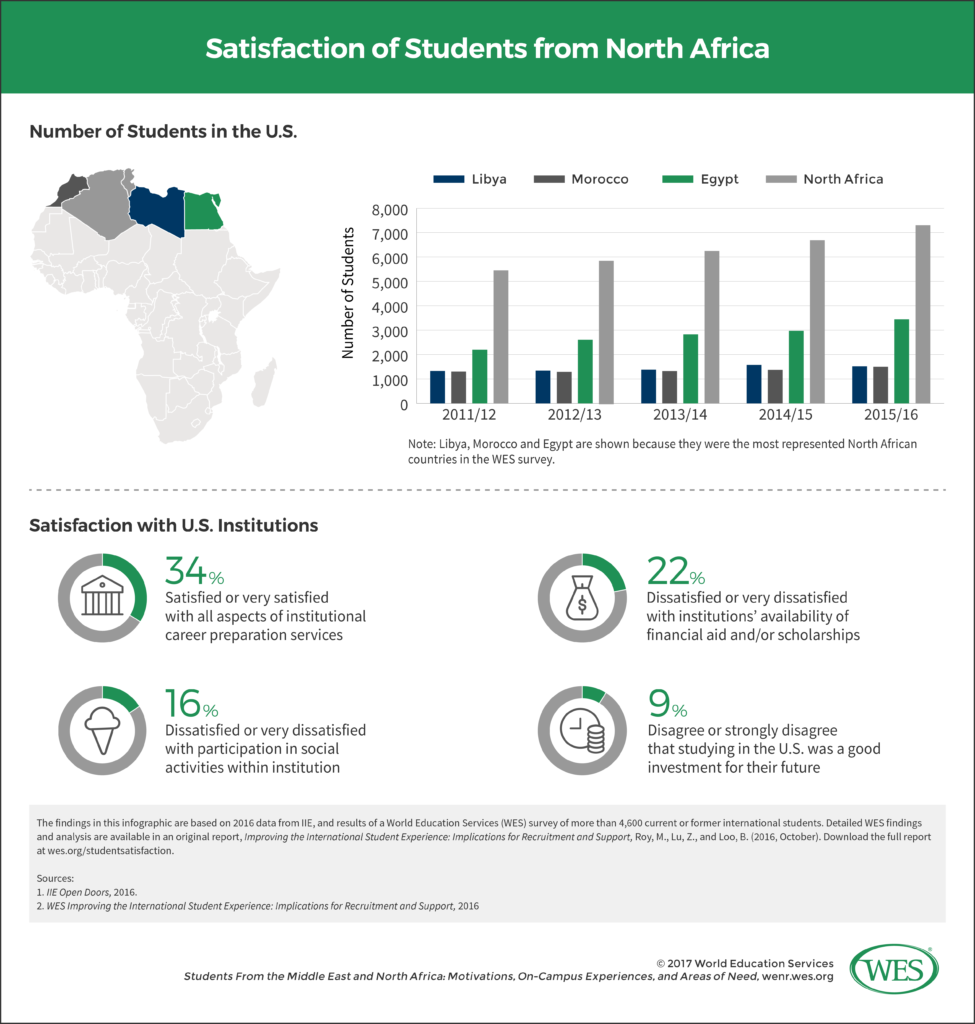

International students from North Africa comprise a relatively smaller pool within the overall region of Middle East and North Africa (MENA). However, their presence on U.S. campuses has shown considerable growth in the past five years, especially from markets such as Egypt, Libya, and Morocco. New Open Doors data reveals that 2015/16 saw a 9 percent increase over the year prior in the number of North African students enrolled in U.S. institutions.

While there are already existing resources on international students from the MENA region, the ratio of students from Middle East is so high that a lot of the evidence largely aims for students from this region and often the same assumption is made for students from North Africa. Given the stark difference in the academic preparedness and financial capabilities of students from Middle East and those from the North Africa region, this section seeks to tease out the details, and offer insights on the distinct experiences of students from North Africa.

Besides the opportunity to obtain a better education outside their home country (the top motivation among all the respondents we surveyed), one of the biggest additional motivations for students from North Africa was the “opportunity to gain work experience outside their home country.” This was much higher among North African students as compared to their counterparts from the Middle East (43 percent versus 25 percent). Our findings also suggest that students from the North African region, which have been affected by economic instability, political turmoil and civil war, and inadequate support for higher education, view study abroad as a pathway to future immigration. Eleven percent of respondents cited future immigration considerations as one of their top motivations for studying abroad, in comparison to seven percent of respondents from Middle East.

The top factors that influenced North African students’ decision to enroll at a U.S. institution, rather than at an institution anywhere else in the world, include:

- “The availability of a desired program” (58 percent North Africa versus 57 percent Middle East)

- “The institution’s reputation” (51 percent North Africa and 46 percent Middle East)

- “Earning potential after graduation” (40 percent North Africa and 36 percent Middle East)

- “Cost of study” (17 percent North Africa 10 percent from Middle East)

Once on campus, tuition fees and expenses related to cost of living are cited as the top challenge by North African students. These struggles are much more acute than they are for students from Middle Eastern countries (55 percent versus 44 percent). North African students are somewhat more dissatisfied with “institutions’ availability of financial aid and/or scholarships” than students from the Middle East (22 percent versus 19 percent).

Students from North Africa identify the ability to gain work experience outside of the home country and the opportunity to increase their earning potential after graduation as key motivators for coming to the U.S. However, relative to students from other regions and countries, the students from North Africa tend to disagree more frequently with the statement “studying in the U.S. was a good investment for my future” than students from other regions (9 percent versus 3 percent overall). In fact, the dissatisfaction rates among North African respondents with regard to the overall experience in the U.S. was high, both compared to international students more generally and compared to those from the MENA region. MENA students’ overall dissatisfaction with their U.S. academic experience was relatively higher than other regions/countries (16 percent MENA versus 9 percent overall). Dissatisfaction among respondents from North Africa and the Middle East showed an even greater disparity: 25 percent versus 14 percent.

This overall dissatisfaction among North African students was also high, despite a moderate to high level of satisfaction with a variety of specific institutional services, such as academic and career support. North African respondents were also relatively more dissatisfied with their social interactions such as “opportunities to participate in social activities within the institution” (16 percent versus 9 percent overall) and “opportunities to interact with and learn from students of other cultures” (14 percent versus 8 percent overall). Some researchers have noted that these areas of dissatisfaction may be attributable to the financial challenges that may contribute to “feelings of homesickness, psychological stress, alienation and isolation, [and] reduced time for study and social activities given the need to work” (Evive, L. G. 2009).[3]Evive, L.G. (2009) Challenges faced by African international students at a metropolitan research university: A phenomenological case study. Retrieved from: http://libres.uncg.edu/ir/uncc/f/Evivie_uncc_0694D_10077.pdf

On the positive side, North African students reported relatively high rates of satisfaction rates with some campus support services such as housing and accommodation, academic advising, orientation programs. Compared to their global peers and their peers in the Middle East, students from North Africa are relatively satisfied with institutional career preparation services (34 percent average satisfaction versus 28 percent in the Middle East, and 33 percent among surveyed students overall). (WES research has found that career services is one of the campus support services that received the lowest satisfaction from all international students – and that is, consequently, one of the potential areas for greatest improvement and potential dividends in the form of greater international student interest.)

Recommendations for Institutions

International students from the MENA region continue to look at the U.S. as an important study destination. However, in the face of the shifting geopolitical and economic landscape, it is important for institutions to carefully examine these students’ needs, interests, and motivations.

Institutions seeking to attract students from the MENA countries should:

- Seek to understand and support students’ financial needs, and to set their expectations about available supports early on. Transparency at the recruitment stage can also help set student expectations about the availability of on-campus jobs and available scholarships, so that students aren’t disappointed once they reach campus. Due to a lower satisfaction with the overall education experiences in the U.S. from North African students, it is important for institutions to carefully examine the needs and interests of this segment.

- Provide career support services that explicitly support Middle Eastern student groups such as Iranians and Israelis, as well as for North African students seeking to obtain professional experiences outside of their home countries. Some of the support services could be providing help to students on résumés, cover letters, and interview skills, largely due cultural differences in these practices and also help connecting students directly with employers through career fairs and networking events, to help them find internships and jobs (Loo, 2016).[4]Loo, B. (2016). Career services for international students: fulfilling high expectations. New York: World Education Services. Retrieved from http://www.wes.org/ras.

- Provide intensive English language training for struggling students from Middle Eastern countries. Better ESL support addresses multiple needs: It can increase chances of academic success, improve social connections, and decrease homesickness.

- Develop culturally sensitive programs and orientations to meet the needs of the Middle Eastern international students, and ask current students from the region for suggestions by continuously measuring and monitoring their satisfactions and experiences. Cultural differences may render students from the Middle East uncomfortable when it comes to using an institutions’ student counselling and advising services. In particular, services such as counseling and therapy are relatively less accepted in Middle Eastern cultures. Lack of English language proficiency may make it even more unlikely that these students will seek out such services (Heyn, M. E. 2013).[5]Heyn, M.E. (2013) Experiences of Male Saudi Arabian International Students in the United States. Retrieved from: http://scholarworks.wmich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1169&context=dissertations

References

| ↑1 | Saudi Arabia, Iran, Israel and Jordan are discussed because they were the most represented Middle Eastern countries in the WES survey. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | So far, this predication has not panned out in the U.S. Between 2014/15 and 2015/16, overall student numbers have been growing quite strongly in all OPEC countries except for Libya. There has been strong growth in big countries like Nigeria (+12.4%). Algeria (+9.1%) or Iran (+8.8%). Qatar grew by 15.3%. This may change well in 2017, but the latest U.S. data we have reports growth. Growth rates have slowed in most countries, but increased in some (Qatar, Algeria). |

| ↑3 | Evive, L.G. (2009) Challenges faced by African international students at a metropolitan research university: A phenomenological case study. Retrieved from: http://libres.uncg.edu/ir/uncc/f/Evivie_uncc_0694D_10077.pdf |

| ↑4 | Loo, B. (2016). Career services for international students: fulfilling high expectations. New York: World Education Services. Retrieved from http://www.wes.org/ras. |

| ↑5 | Heyn, M.E. (2013) Experiences of Male Saudi Arabian International Students in the United States. Retrieved from: http://scholarworks.wmich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1169&context=dissertations |