Wilson Macha, Chris Mackie, and Jessica Magaziner, Knowledge Analysts at WES

The Philippines is a unique country. Only slightly larger than the U.S. state of Arizona in land mass, it is the world’s second-largest archipelago after Indonesia, consisting of more than 7,000 islands. It is also the world’s 12th most-populous country with just over 103 million people as of 2016 [2].

Notably, the Philippines is the only pre-dominantly Christian country in Asia (roughly 80 percent of the population is Roman Catholic). Equally notable, English is a national language in the Philippines next to Filipino (Tagalog) and spoken by about two-thirds of the population, although there are still some 170 additional Malayo-Polynesian languages in use throughout the archipelago.

Both the country’s religious makeup and its anglophony are the result of colonialism. The Philippines was a Spanish colony for more than three centuries, a fact that shaped religious belief systems, before the U.S. occupied it in 1898 and ruled the country for nearly five decades, until independence in 1946. U.S. colonialism had a formative impact on the development of the modern Philippine education system and various other aspects of Philippine society. With the imposition of English in sectors like education, news media, and trade, the Spanish language became marginalized and faded. In 1987, Spanish was dropped as an official language and is today only spoken by a small minority of Filipinos.

Deteriorating Human Rights Situation

In 2013, the Philippine government initiated the extension of the country’s basic education cycle from ten to twelve years – a major reform that former Education Secretary Armin Luistro has called “the most comprehensive basic education reform initiative ever done in the country since the establishment of the public education system more than a century ago [3]”. Over the past two years, however, news from the Philippines was mostly dominated by extralegal killings, after populist President Rodrigo Duterte, elected in 2016, unleashed a brutal “war on drugs” that Human Rights Watch has described as the “worst human rights crisis [4] since the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos”. In a quest to eradicate the sale and use of drugs, more than 12,000 people, including many innocent victims, have been gunned down by the country’s police, armed forces and vigilantes without any form of legal process. Most of the victims are poor and from the country’s congested cities.

Other recent developments included an intensification of the armed conflict in the southern region of the country, in which separatist rebels and Islamist terror groups like Abu Sayyaf are fighting for greater autonomy or the creation of an independent state for the Muslim Moro minority (officially 5 percent of the population, primarily located on the island of Mindanao). Heavy military fighting in 2017 [5] triggered the imposition of martial law in the Mindanao region, with President Duterte publicly contemplating the extension of martial law to other parts of the country [6] – an announcement that raised the specter of a further erosion of civil liberties in the Philippines.

Duterte’s “war on drugs” and his authoritarian ambitions are not without detractors – the Catholic Church of the Philippines, for instance, has condemned [7] the extrajudicial killings. As of now, however, Duterte’s hard-line policies are supported by a majority of the Filipino population. The President held a sky-high approval rating of 80 percent [8] in opinion polls conducted in December 2017 – a far higher rating than any of the three preceding presidents [9].

Economic Outlook and Poverty

The deteriorating human rights situation in the Philippines has so far done little to slow economic growth. The Philippine economy is booming and has, in fact, grown faster than all other Asian economies except China and Vietnam in recent years. In 2017, the country’s GDP increased by 6.7 percent and is projected to continue to grow by more than 6 percent annually in 2018 and 2019 [10].

By some measures, economic growth in the Philippines is socially inclusive: according to official statistics [11], the country’s poverty rate decreased from 26.6 percent in 2006 to 21.6 percent in 2015. The World Bank noted [12] that between “…. 2012 and 2015, household income among the bottom 40 percent of the income distribution rose by an average annual rate of 7.6 percent”. At the same time, poverty remains a major and pervasive problem in the Philippines, with efforts to reduce the problem progressing slowly and lagging behind improvements made in other Southeast Asian countries. Income disparities are rampant and economic growth is mostly concentrated in urban centers, while many rural regions remain plagued by extreme levels of poverty. According to the Asian Development Bank [13], close to 25 million Filipinos still existed on less than USD $1.51 per day in 2010.

Problems in Education and Education Reforms: An Overview

In 2017, the National Economic and Development Authority of the Philippines published the Philippine Development Plan, 2017-2022 [14], detailing the country’s aspirations for the next five years. The plan envisions the Philippines becoming an upper-middle income country by 2022, based on more inclusive economic growth that will reduce inequalities and poverty, particularly in rural areas. Human capital development is a key element in this strategy and has been the impetus behind various political reforms over the past years. Recent education reforms have sought to boost enrollment levels, graduation rates and mean years of schooling in elementary and secondary education, and to improve the quality of higher education.

Problems in the School Sector

Many of these reforms were adopted against a backdrop of declining educational standards in the Philippine education system during the first decade of the 21st century. A UNESCO mid-decade assessment report [15] of Southeast Asian education systems, published in 2008, for example, found that participation and achievement rates in basic education in the Philippines had fallen dramatically, owed to chronic underfunding. After rising strongly from 85.1 percent in 1991 to 96.8 percent in 2000, net enrollment rates [15] at the elementary level, for instance, had dropped back down to 84.4 percent by 2005. Also by mid-decade, elementary school dropout rates [16] had regressed back to levels last seen in the late 1990s. The completion rate [17] in elementary school was estimated to be below 70 percent in 2005.

At the secondary level, problems were omnipresent as well: the net enrollment rate [16] in secondary education, for example, had by 2005 dropped down to 58.5 percent, after increasing from 55.4 percent to around 66 percent between 1991 and 2000. Tellingly perhaps, the country’s youth literacy rate [15], while still being high by regional standards, fell from 96.6 percent in 1990 to 95.1 percent in 2003, making the Philippines the only country in South-East Asia with declining youth literacy rates.

Such deficiencies were reflected in the poor performance of Filipino students in international assessment tests, such as the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study [18] (TIMSS). In 2003, the last year the Philippines participated in the study, the country ranked only 34th out of 38 countries [19] in high school mathematics and 43rd out of 46 countries in high school science. Education spending as a percentage of overall government expenditures, meanwhile, declined from 18.2 percent in 1998 to 12.4 percent in 2005 [20]. Between 2003 and 2005 alone, average annual spending [17] per public elementary and secondary school student fell from PHP 9,500 (USD $182.7) to PHP 8,700 (USD $167.3) in real terms.

Policy Response

To address these shortcomings, the Philippine government initiated structural changes in the basic education system and significantly boosted education expenditures. Crucially, the “Kindergarten Education Act [21]”, passed in 2011, enacted a mandatory pre-elementary year of Kindergarten education, while the “2013 Basic Education Act [22]”, extended the elementary and secondary education cycle from 10 to 12 years. The importance of this new 12-year education cycle (K-12), which adds two years of mandatory senior secondary schooling for every Filipino student, cannot be understated. Until the reforms, the Philippines was one of only three countries in the world (the other two being Angola and Djibouti), with a 10-year basic education cycle. As such, the K-12 reforms are an essential step to improve the global competitiveness of the Philippines and bring the country up to international standards. Implementation of the new system is progressing on schedule and the first student cohort [23] will graduate from the new 12-year system in 2018.

In addition, education spending was increased greatly: between 2005, when it hit its nadir, and 2014, government spending on basic education, for instance, more than doubled. Spending per student in the basic education system reached PHP 12,800 [17] (USD $246) in 2013, a drastic increase over 2005 levels. And education expenditures have grown even further since: In 2017, for instance, allocations for the Department of Education were increased by fully 25 percent [24], making education the largest item on the national budget. In 2018, allocations for education increased by another 1.7 percent and currently stand at PHP 533.31 billion [25] (USD $ 10.26 billion), or 24 percent of all government expenditures (the second largest item on the national budget). The higher education budget, likewise, was increased by almost 45 percent between 2016 and 2017. It should be noted, however, that some of the spending increases are simply designed to cover additional costs stemming from the K-12 reforms. To accommodate the reforms, 86,478 classrooms were constructed, and over 128,000 new teachers hired in the Philippines between 2010 and 2015 [26] alone.

Outcomes of the Reforms Thus Far

The government investments in education have led to substantial advances in standard indicators of learning conditions [17], such as student-teacher and student-classroom ratios, both of which improved significantly from 2010 to 2013, from 38:1 to 29:1 and from 64:1 to 47:1, respectively. Elementary school completion rates [17] also climbed from their 2005 low of under 70 percent to more than 83 percent in 2015 [27]. Net secondary school enrollment rates, meanwhile, increased from under 60 percent in 2005 to 68.15 percent in 2015.

The biggest advances, however, were made in pre-school education. After the introduction of one year of mandatory Kindergarten education in 2011, the net enrollment rate in Kindergarten [28] jumped from 55 percent (2010) to 74.6 percent in 2015. Also encouraging was the fact that poorer families benefited strongly from the reforms. The World Bank noted [17] that in “2008, the gross enrollment rate in kindergarten for the poorest 20 percent of the population was 33 percent, but this had increased to 63 percent by 2013. Levels of kindergarten enrollment in the Philippines now compare favorably with rates in other middle-income countries both within the region and globally”.

That said, the Philippines keeps trailing other South East Asian countries in a variety of education indicators and the government has so far fallen short on a number of its own reform goals. Strong disparities continue to exist between regions and socioeconomic classes – while 81 percent of eligible children from the wealthiest 20 percent of households attended high school in 2013 [17], only 53 percent of children from the poorest 20 percent of households did the same. Progress on some indicators is sluggish, if not regressing: completion rates at the secondary level, for example, declined from 75 percent in 2010 to 74 percent in 2015, after improving in the years between.

Importantly, the Philippines government continues to spend less per student as a share of per capita GDP [29] than several other Southeast Asian countries, the latest budget increases notwithstanding. It also remains to be seen how the K-12 reforms will affect indicators like teacher-to-student ratios. In October 2015, it was estimated, that the government still needed to hire 43,000 teachers [30] and build 30,000 classrooms in order to implement the changes. Strong population growth will also continue to put pressures on the education system. The Philippines has one of the highest birth rates in Asia, and the government expects the population to grow to 142 million people [31] by 2045.

Outcomes in Higher Education

In higher education, the government seeks to expand access and participation, but even more importantly, tries to improve the quality of education. The Philippine National Development Plan is quite outspoken on this subject and notes [14] that while “the number of higher education institutions (HEIs) in the Philippines is ten times more than its neighboring countries’, the Philippines’ lackluster performance in producing innovators… , researchers (81 researchers per million population versus 205 in Indonesia and 115 in Vietnam), and knowledge producers (28 out of 777 journals or 3.6 percent are listed under Thomson Reuters, Scopus, or both) indicates … that the country has lagged behind many of its ASEAN neighbors in producing the … researchers, innovators … and solutions providers needed to effectively function in a knowledge economy”.

Participation in higher education in the Philippines has, without question, expanded strongly in recent years. The gross tertiary enrollment rate increased from 27.5 percent in 2005 to 35.7 percent in 2014 [32], while the total number of students enrolled in tertiary education grew from 2.2 million [33] in 1999 to 4.1 million [34] in 2015/16. Filipino experts have noted that the number of graduates from higher education programs has recently “exceeded expectations [14].” The bold decision of President Duterte in 2017 to make education at state universities and colleges tuition-free [35] may help to further boost enrollments, even though critics contend that the costly move will sap the public budget while providing few discernible social benefits [36]. These critics maintain that tuition-free education will primarily benefit wealthier students since only 12 percent of students at state institutions come from low-income households [36].

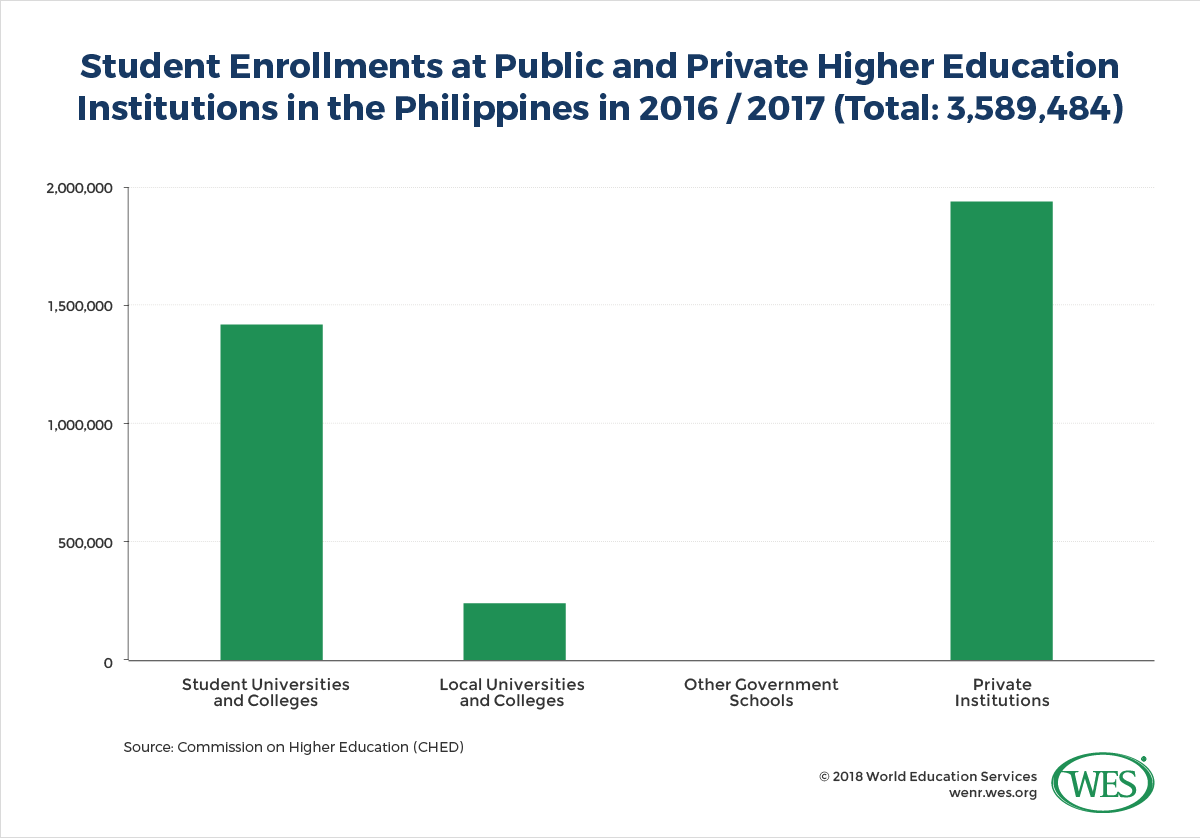

At the same time, the K-12 reforms will inevitably lead to decreased higher education enrollments, at least in the short-term, since many of the students that would usually have entered higher education after grade 10 now have to complete two additional years of school. Between 2015/16 and 2016/17, the total number of tertiary students already dropped from 4.1 million to 3.6 million [34] – a decrease that is particularly apparent when looking at undergraduate enrollments. Data from the Commission on Higher Education (CHED) shows that undergraduate enrollments dropped by 12.7 percent [37] between the 2015/16 and 2016/17 academic years, and is expected to drop by a further 22 percent in 2017/18, before starting to recover in 2018/19, when the first K-12 cohorts start to enter higher education.

This downturn will affect HEIs and lead to declining revenues during the transition period – a fact that will primarily hurt private HEIs, since nearly all of their funding comes from tuition fees. As a result, CHED anticipates that approximately 25,000 staff [39], including faculty and administrators, will lose their jobs. Changes will also be made to the undergraduate curriculum. Since the previous curriculum compensated for the fact that students entered with only ten years of secondary education, the revised curriculum will have greatly reduced general education requirements [39].

Quality Improvements and Internationalization

Regarding qualitative improvements, achievements are notable in a number of areas, including a slight increase in the number of higher education faculty holding higher degrees. The percentage of instructors with master’s and doctoral degrees grew from 38.87 percent and 11.09 percent in 2010, respectively, to 40.34 and 12.62 percent in 2015 [14]. The number of HEIs with accredited education programs, which is not mandatory in the Philippines, increased by more than 40 percent between 2010 and 2016/17 [40], while the pass rates of candidates sitting for professional licensing exams, a measure of academic effectiveness, jumped from 33.9 to 58.6 percent [14] between 2010 and 2015.

In an attempt to boost the country’s research output, the government in 2017 also institutionalized [41] the so-called “Balik (Returning) Scientist Program,” an initiative that was first created in the 1970s to incentivize highly skilled Filipino researchers working abroad to return to the Philippines. Benefits provided through the program include research grants, free health insurance, and relocation allowances. As international education consultant Roger Chao Jr has pointed out [42], it remains to be seen, however, how effective the program will be, given that the offered incentives and research funding may not be competitive enough to lure established scientists back to the Philippines.

Like most Asian countries, the Philippines also seeks to internationalize its education system and promotes transnational education (TNE) partnerships with foreign HEIs. To formalize this process and assure the quality of the programs offered, CHED in 2016 established concrete guidelines [43] for transnational programs. Importantly, programs can only be offered in collaboration with a Philippine partner institution. Both the foreign provider and the Philippine partner institution must also be officially recognized and seek authorization from CHED, which is initially granted for a one-year period for graduate programs, and for two years in the case of undergraduate programs.

CHED has entered agreements with a number of countries [44], predominantly in Europe, but its most significant relationship is with the United Kingdom. The British Council [44], the U.K.’s designated organization to promote international exchange, considers the Philippines an ideal location for a TNE hub, due to its expanding population of university-age students, CHED’s commitment to internationalization, and the use of English as a language of instruction in a majority of higher education programs. In 2016, CHED and the British Council entered an agreement [45] designed to “support twinning, joint degree programmes, dual degrees and franchise models in priority fields of study between institutions in the Philippines and the UK [46].” In 2017, this was followed by ten Philippine universities, including the country’s top institutions, being designated to receive seed funding to establish TNE programs with British partner universities. The initiative is funded with UK £ 1million (USD $1.4 million) from CHED and UK £ 500,000 (USD $698,000) from the British Council [47]. Programs are slated to commence in the 2018/19 academic year.

International Student Mobility

Outbound Mobility

The thriving TNE partnership between the UK and the Philippines will offer Filipino students access to UK education programs and reflects that there is a growing demand for international education in the country. Over the past 15+ years, the number of Filipino students enrolled in degree programs abroad alone almost tripled from 5,087 students in 1999 to 14,696 students in 2016 (UNESCO Institute of Statistics [33] – UIS). Given the population size of the Philippines, however, this is not an overly high number when compared, for example, to Vietnam’s 63,703 outbound degree students in 2016. The outbound mobility rate (number of outbound students among all students) in the Philippines is low and remains significantly below the outbound mobility rate of neighboring countries like Malaysia, Vietnam or Indonesia.

That said, the number of outbound degree students has increased consistently over the years and there is good reason to believe that international student flows from the Philippines will expand in the future. Population growth and the prospect of increasing economic prosperity imply that the total number of tertiary students in the country is set to increase rapidly – the Philippines is expected to be among the world’s top 20 countries in terms of tertiary enrollments by 2035 [48]. Filipino students are also well-suited for international mobility, due to their English language abilities. What is more, the K-12 reforms will remove barriers to academic mobility: In an international environment accustomed to 12-year secondary school qualifications, the anachronistic 10-year school system hampered the mobility of Filipino students, both in terms of formal academic qualifications and academic preparedness. Many foreign institutions, for instance, considered the Philippine Bachelor’s degree only equivalent to two years of undergraduate study [49] – a fact that complicated graduate admissions. As we pointed out in an earlier article on the subject, the K-12 reforms are therefore likely to increase outbound mobility [50].

Future mobility from and to the Philippines may also be facilitated by further economic and political integration in the ASEAN community. The long-term potential for intra-regional student mobility in this dynamic region of 600 million people is tremendous, especially since the ASEAN member states are trying to harmonize education systems and ease international mobility.

Destination Countries

According to the latest available UIS data [33], Australia is presently the most popular destination country of Filipino students enrolled in degree programs abroad, hosting 4,432 Filipino students (2015). The U.S. was the second most popular destination with just over 3,000 degree students. New Zealand, the U.K. and Saudi Arabia rounded out the top five with 1,105, 698 and 693 Filipino students, respectively. Italy hosted 561 Filipino students and Japan hosted 488. The remaining three countries of the top ten, the United Arab Emirates, Korea and Canada, all had Filipino students numbering in the mid to low 400s.

Four of the top five destinations are English-speaking countries, demonstrating the interest of Filipino students in English-language destinations, with the popularity of Australia and New Zealand likely owed to their geographic proximity. There have been some shifts in destinations, however. While Australia has now overtaken the U.S., which used to be top destination until recently, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have emerged as new study destinations among the top ten. The latter trend coincides with strong increases in labor migration to these two countries, both of which have been the main destinations of Filipino overseas workers for years. There are also a relatively large number of international Philippine schools [51] in Saudi Arabia, catering to the children of these migrant workers. It is well possible that some of these children continue their post-secondary education in Saudi Arabia.

When comparing international student statistics, it is important to note that these statistics can show substantially deviating numbers, due to factors like different methods of data capture or different definitions of ‘international student’ (degree students versus students enrolled in language programs) etc. The Canadian government, for instance, reports vastly different international student numbers than the UIS. According to these statistics [52], the number of Filipino international students in Canada has increased by 275 percent between 2006 and 2015, from 817 students to 3,065 students, making the Philippines the 20th largest source country of international students in Canada in 2015. The Canadian government seeks to further boost the inflow of Filipino students, and in 2017 launched a so-called “Study Direct Stream Program [53]” in partnership with CHED. The program will streamline and shorten visa processing times, and ease the financial documentation requirements for Filipino students.

In the U.S., by contrast, the Philippines is presently neither a major sending country nor a dynamic growth market. Enrollments of Filipino students have remained largely stagnant and slightly decreased over the past 15+ years. According to the Institute of International Education’s (IIE) Open Doors [54] data, there were 3,130 Filipino students in the U.S. in 2000/01, 3,758 students in 2005/06 and 3,006 students in 2016/17. The current number reflects an increase of 4.6 percent over 2015/16, but given the fluctuations in previous years, it remains to be seen if this can be taken as a sign of a lasting upswing. As of now, the long-standing popularity of the U.S. as an immigration destination for Filipinos [55] is not matched by corresponding international student flows. The Filipino students that are in the U.S. are predominantly enrolled at the undergraduate level (54 percent), while 30 percent studied in graduate programs and 16 percent were registered in non-degree programs and OPT [54].

Inbound Student Mobility

There is only limited data available for inbound students in the Philippines. The number of foreign students in the country is small by international comparison, but not insignificant – the Philippines hosts substantially more foreign students than the highly dynamic outbound [56] market of Vietnam, for example.

According to the UIS [33], the number of inbound degree-seeking students in the Philippines has fluctuated strongly over the years and ranged from 3,514 students in 1999 to 5,136 students in 2006 and 2,665 students in 2008, the last year for which the UIS provides data. More recent data from CHED [57] and the IIE’s Project Atlas [58] (which is based on CHED data) reports higher, if equally fluctuating, numbers. Accordingly, there were 7,766 foreign students in the country in 2011/12, followed by 6,432 students in 2014/15, and 8,208 students in 2015/16.

While there is no current data on countries of origin, most of these students come from other Asian countries. According to the Philippine Bureau of Immigration, the top two sending countries [49] between 2004 and 2009 were South Korea and China – with strong growth rates in both cases. Also notable are a growing number of Indian students and a tremendous increase in Iranian student enrollments during that time period. In 2011/12, Koreans accounted for 21.5 percent [57] of international enrollments, followed by Iran and China, with slightly above 13 percent of students each.

In a 2013 study [49] on student mobility in Asia, UNESCO noted that the Philippines benefits from “the use of English as the medium of instruction…; a wide variety of academic programmes; the relatively low cost of living and affordable tuition and other school fees”. But what the strong presence of Korean students, in particular, suggests is that the country’s popularity as an English language training (ELT) destination is one of the strongest drivers of inbound mobility. For Koreans and other Asian students, the Philippines is a popular ELT “budget destination” that offers much lower tuition fees than the UK, Australia, Canada or the U.S., is easily reachable via short direct flights, and affords students the opportunity to combine ELT with beachside vacations.

As a result, ELT enrollments in the country are surging. The Philippines’ Ambassador to the U.S. affirmed in 2015 [59], that “there are more and more Koreans that are studying English in the Philippines… In 2004, there were about 5,700… The following year, it tripled to about 17,000, in 2012 it was about 24,000. So we’re seeing an increasing number of Koreans. But they’re also from other countries: Libya, Brazil, Russia.” ICEF Monitor [60] recently noted that this boom has caused more and more ELT providers to set up shop in the Philippines, and led the Filipino government to aggressively market the country as an ELT destination.

Administration of the Education System

Education in the Philippines is administered by three different government agencies, each exercising largely exclusive jurisdiction over various aspects of the education system.

The Department of Education [61] oversees all aspects of elementary, secondary and informal education. It supervises all elementary and secondary schools, both public and private. The Department is divided [62] into two components: the central office in Manila and various field offices, of which there are currently 17 regional offices and 221 provincial and city schools divisions. The central office sets overall policies for the basic education sector, while the field offices implement policies at the local level. The Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) has its own department of education, but for the most part follows national guidelines and uses the national school curriculum.

The Department of Education also has a number of agencies supervising programs that fall outside the country’s formal education system. The Bureau of Alternative Learning System (BALS), for instance, oversees education programs designed for “out-of-school children, youth and adults who need basic and functional literacy skills, knowledge and values.” Two of its major programs [63] are the Basic Literacy Program (BLP), which aims to eliminate illiteracy among out-of-school children and adults, as well as the “Continuing Education: Accreditation and Equivalency (A&E) Program”, which helps school dropouts to complete basic education outside the formal education system.

Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) in the Philippines is supervised by the Technical Education and Skills Development Authority (TESDA) [64]. TESDA oversees TVET providers, both public and private, and acts as a regulatory body, setting training standards, curricula and testing requirements for vocational programs.

The main authority in tertiary education is the Commission on Higher Education (CHED) [65]. Directly attached to the Office of the President, CHED has far-reaching responsibilities. It develops and implements higher education policies and provides quality assurance through its oversight of post-secondary programs and institutions, both public and private. CHED sets minimum standards for academic programs and the establishment of new HEIs. It also suggests funding levels for public HEIs and determines how HEIs can use these funds.

Elementary Education

Elementary education in the Philippines consists of six years of schooling, covering grades 1 to 6 (ages 6 to 12). Before the adoption of the K-12 reforms, elementary education was the only compulsory part of the basic education cycle. With the reforms, however, compulsory education has been extended and is now mandatory for all years of schooling, inclusive of grade 12.

It is now also mandatory that children complete one-year of pre-school Kindergarten education before enrolling in elementary school. While it appears that this is not yet consistent practice throughout the entire country, current legislation mandates that all children enroll in Kindergarten at the age of five. Kindergarten education, like all other parts of public schooling, is free of charge at public schools. Upon completion of the mandatory pre-school year, pupils are eligible to attend elementary school – there are no separate admission requirements.

The elementary school curriculum [66] was recently revised and includes standard subjects like Filipino, English, mathematics, science, social science, Philippine history and culture, physical education and arts. One notable and important change, however, is that minority languages (“mother tongues”) are now being used as the language of instruction in the first years of elementary education in areas where these languages are the lingua franca. There are currently 19 recognized minority languages [67] in use. English and Filipino are introduced as languages of instruction from grades 4 to 6, in preparation for their exclusive use in junior and senior secondary high school.

Secondary Education

Pre-reform: Prior to the 2016/17 school year, when the first cohort entered grade 11 of the new senior secondary cycle, basic education ended after four years of secondary education (grades 7 to 10). Although freely available in public schools to all interested students, these four final years of basic education were not compulsory. Graduating students were awarded a Certificate of Graduation at the end of grade 10, and would progress either to higher education, TVET, or employment.

Post-reform: With the enactment of the K-12 reforms, secondary education was extended from four to six years and divided into two levels: four years of Junior High School (JHS) and two years of Senior High School (SHS), giving the basic education cycle a structure of K+6+4+2. All six years of secondary education are compulsory and free of charge at public schools. Since the construction of public senior high schools and classrooms still lags behind the need created by the K-12 reforms, however, a new voucher system [68] was put in place to subsidize SHS study at private schools. That said, the voucher amount is capped and does not fully cover tuition at most private schools, keeping this option out of reach for socially highly disadvantaged families.

Private Schools

The size of the private sector in the Philippine school system is considerable. The government already decades before the K-12 reforms started to promote public-private partnerships in education. In these partnerships, the government sponsors study at low-cost private schools with tuition waivers and subsidies for teacher salaries in an attempt to “decongest” [69] the overburdened public system. The Philippine “Educational Service Contracting” program (ESC) is, in fact, one of the largest such systems in the world [70]. It provides the state with a way to provide education at a lower cost than in public schools, with parents picking up the rest of the tab – a fact that has caused critics to charge that the government is neglecting its obligation to provide free universal basic education [70].

Private high schools in the Philippines teach the national curriculum, must be officially approved and abide by regulations set forth by the Department of Education. In 2014, 18 percent of secondary students, or 1.3 million students [70], were enrolled in private schools. Fully 5,130 out of 12,878 [71] secondary schools in the Philippines in 2012/13 (about 40 percent) were privately owned. The number of ESC tuition grantees increased by 40 percent [69] between 1996 and 2012 and accounted for almost 60 percent [70] of all private high school students in 2014, reflecting that publicly subsidized private education is a growing trend with increasing numbers of low-cost private schools now entering the Philippine market in the wake of the K-12 reforms.

Junior High School (JHS)

JHS comprises grades 7 to 10 (ages 12 to 16). Students who complete elementary education at grade 6 automatically progress to JHS – there are no separate entry requirements at both the junior and senior secondary levels, although private schools may require passing of an entrance examination. The JHS core curriculum includes the same subjects as the elementary curriculum, with English and Filipino being used as the language of instruction, depending on the subject.

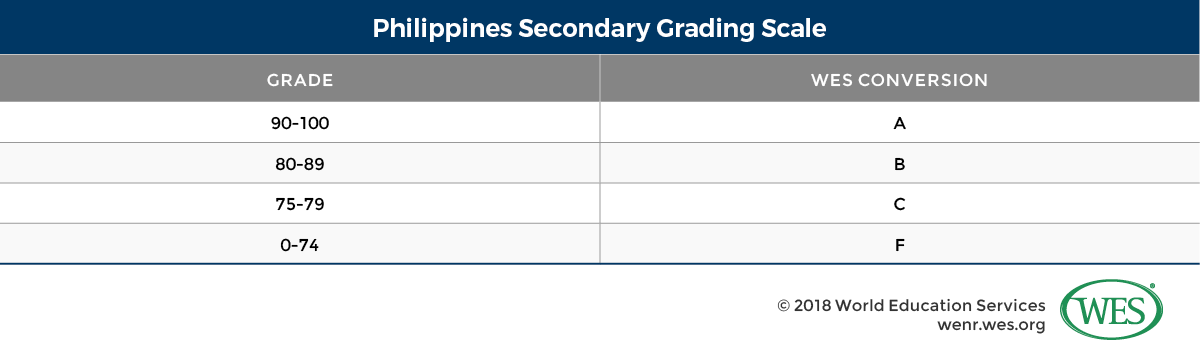

Pupils are assessed based on written assignments, performance tasks and quarterly assessments (based on tests and/or performance tasks). The minimum passing grade for both single subjects and the cumulative year-end average required for promotion is the grade of 75 [72] (out of 100). Students with lower grades must take remedial classes and improve their grades in order to progress to the next grade. There are no final graduation examinations at both the junior and senior secondary levels.

Pupils interested in pursuing TVET may simultaneously start to explore Technology and Livelihood Education (TLE) [73] subjects in grades 7 and 8, and have the option to start studying these subjects more extensively in grades 9 and 10. Those that complete a sufficient number of hours in TLE subjects and pass TESDA assessments may be awarded a TESDA Certificate of Competency or a National Certificate (see TVET section below).

[74]

[74]

Senior High School (SHS)

SHS consists of two years of specialized upper secondary education (grades 11 and 12, ages 16 to 18). Students are streamed into academic specialization tracks with distinct curricula. Before enrolling, students choose a specialization track [26], being restricted in their choice only by the availability of that specialization at the school they plan to attend. The four tracks are:

- Academic Track

- Technical-Vocational-Livelihood (TVL) Track

- Sports Track

- Arts and Design Track

Students in all tracks study a core curriculum of 15 required subjects from seven learning areas, which include: languages, literature, communication, mathematics, philosophy, natural sciences, and social sciences. The grading scale and methods of assessment used in SHS are the same as in JHS, but with a stronger emphasis on performance tasks. Upon completion of grade 12, students are awarded a high school diploma [75].

The Academic Track is designed to prepare students for tertiary education. It is further divided into four strands [76]: general academic; accountancy, business and management (ABM); humanities and social sciences (HUMSS); and science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM).

The TVL Track [77] is intended for students looking to enter the labor force or pursue further TVET after graduation. It is also divided into four strands [78]: home economics; agriculture/fishery; industrial arts; and information and communications technology (ICT). Graduates that pass the relevant TESDA assessment tests are simultaneously eligible for the award of a TESDA National Certificate I or II (see TVET section below).

The Sports and Arts and Design Tracks are intended to impart “middle-level technical skills” for careers in sports-related fields and creative industries. Enrollments in these two tracks will be comparatively small, however. While the Department of Education expected [79] an estimated 609,000 students to enroll in the academic track, and another 596,000 students to enroll in the TVL track in 2016, only 20,000 students were anticipated to opt for the sports or arts and design tracks.

Overall, it is expected that the new overhauled K-12 curriculum will lead to greatly improved educational outcomes, since it helps “decongest” [80] the highly condensed prior 10-year curriculum. Filipino educators have blamed the old compressed curriculum, at least in part, for the high dropout rates and lack-luster test scores in recent years, since it did not afford students the time necessary to absorb and learn all the material presented to them.

The Qualifications Framework of the Philippines

In 2012, the government established an official qualifications framework for the Philippines (PQF). The goal [81] of the PQF is to define standards and learning outcomes, ease mobility between different education and training sectors in the Philippines, and to align Philippine qualifications with international qualifications frameworks to facilitate international mobility. Qualifications in the PQF range from secondary-level TVET certificates at levels 1 and 2 to doctoral qualifications at level 8.

Technical Vocational Education and Training (TVET)

TVET in the Philippines is designed to train the Philippine labor force and prepare graduates for medium- skilled employment in various vocations, ranging from agriculture to automotive technology, bookkeeping, business services, computer maintenance, information technology, health services, cookery, tourism and hospitality services, carpentry, seafaring, housekeeping, web design or teaching ESL. There were more than 2,000 different training programs [83] on offer in 2015.

While the TVET sector is smaller in terms of total enrollments and remains less popular than the tertiary sector, it nevertheless has expanded rapidly over the past years. Between 2000 and 2016, the number of students enrolled in TVET programs increased by 295 percent, from 574,017 students [84] to 2.27 million students [85]. Graduation rates in TVET programs have improved greatly in recent years and grew from 83 percent in 2010 to 95 percent in 2016 [85].

Structure

The PQF specifies five levels of TVET qualifications. The National Certificate (NC) I and NC II are placed at the secondary level and are designed to impart practical skills in a “limited range of highly familiar and predictable contexts”. These certificates can be earned by secondary school students at the end of grade 10 or grade 12.

The NC III, NC IV and Diploma are post-secondary qualifications at levels 3 to 5 of the PQF. Programs leading to these types of qualifications generally require prior NCs or a high school diploma for admission and involve training at progressive levels of complexity with a greater theoretical focus, designed to train skilled workers in more supervisory functions. NC programs are usually more applied in nature, whereas diploma programs tend to be more theoretically oriented and often offered at universities.

At the NC level, TVET is competency-based, which means that programs are typically not studied or quantified in a concrete number of semesters or years of study. Instead, training programs are often modularized and self-paced – a fact that allows students who are already employed to pursue TVET without having to adhere to a strict schedule of classes. To earn a qualification, students must acquire a set number of “units of competency”, formally certified in Certificates of Competency (COCs). COCs may be awarded upon completion of a set number of hours of instruction, or demonstrated mastery of certain practical competencies. Assessment may involve oral exams, written tests, employer assessment, portfolio or work projects [86].

It is important to note that NCs and COCs are only valid for a period of five years. After five years, holders of these qualifications must apply for the renewal of their certification and re-registration in a TESDA-maintained Registry of Certified Workers [87]. If TESDA has established new competency standards since the original qualification was issued, applicants must undergo another competency assessment based on the new competency standards.

TVET Institutions and Modes of Delivery

There are three main modes of TVET delivery in the Philippines: institution-based (at schools and centers), enterprise-based (at companies), and community-based (at local government and community organizations).

Institution-based programs are offered by TESDA-administered schools and training centers, as well as by authorized private schools. Some higher education institutions also offer TESDA-approved programs. About half of all TVET students studied in institution-based programs in 2016 [88]. TESDA presently directly maintains 57 schools [89], including 19 agricultural schools, 7 fishery schools and 31 trade schools, as well as 60 regional training centers [90] catering to regional needs. Most TVET schools, however, are privately-owned. About 90 percent [91] of all TVET providers were private as of 2013, even though public institutions continue to enroll greater numbers of students: In 2016, 54.3 percent [88] of TVET students were enrolled in public schools, compared to 45.7 percent in private institutions.

Enterprise-based programs are typically pursued by trainees who are employed or are training for employment at a company. These practice-oriented programs include apprenticeship programs, so-called “learnership” programs, and dual training programs, a training model adopted from Germany which combines training at a workplace with theoretical instruction at a school. Most of these programs are based on a contract between the trainee and the company and are as of now not very common – only slightly more than 3 percent [88] of TVET students were training in enterprise-based programs in 2016. Apprenticeship programs are usually between four and six months in length, whereas learnership programs are simply shorter apprenticeship programs lasting up to three months. Programs in the Dual Training System [92] (DTS), meanwhile, last up to two years, during which trainees acquire practical job skills augmented by part-time study at a school.

Community-based programs are designed to provide TVET for “poor and marginal groups” at the communal level, often in partnership with local government organizations. Based on local needs and resources, these public programs are not only intended to help upskill marginalized populations, but also aim to support NGOs and local government [93].

Quality Assurance

TESDA provides quality control for TVET programs through its “Unified TVET Program Registration and Accreditation System “(UTPRAS [94]). All TVET programs offered at public and private institutions must be taught in accordance with TESDA’s training regulations and be officially registered via UTPRAS. In addition, TVET providers can improve their reputation by seeking accreditation from accrediting bodies like the Asia Pacific Accreditation and Certification Commission [95], but this is a voluntary process and not required for offering TVET programs in the Philippines.

Articulation between TVET and Tertiary Education Sectors

Until now, the transferability of qualifications and study between the competency-based TVET and tertiary education sectors is limited. However, the Philippine government seeks to create a more open and integrated system. In the “Ladderized Education Act of 2014 [96]”, it directed CHED, TESDA and the Depart of Education to establish “equivalency pathways and access ramps allowing for easier transitions and progressions between TVET and higher education”, including “…qualifications and articulation mechanisms, such as, but not necessarily limited to the following: credit transfer, embedded TVET qualification in ladderized degree programs, post-TVET bridging programs, enhanced equivalency, adoption of ladderized curricula/programs, and accreditation and/or recognition of prior learning”. It remains to be seen how these changes will be implemented in the future.

Tertiary Education

Higher Education Institutions

The number of HEIs in the Philippines has grown rapidly over the past decades. Between 2007 and 2016/17 alone, the number of HEIs increased from 1,776 [97] to 1,943 [98]. That makes the Philippines the country with the highest number of HEIs [27] in Southeast Asia. For example, the Philippines has more than four times as many HEIs than Vietnam (445 in 2015 [99]), a country with a similar-size population.

Types of HEIs

There are three types of public tertiary education institutions in the Philippines as classified by CHED:

State universities and colleges [100] or SUCs are defined as public institutions “with independent governing boards and individual charters established by and financed and maintained by the national government“. In order to be classified as a university (as opposed to a college), institutions need to offer graduate programs in addition to a minimum number of bachelor programs in a range of disciplines. There are presently 112 SUCs in the Philippines.

Local colleges and universities [101] are public institutions established and funded by local government units. There are presently 107 local universities and colleges.

Other government schools [102] form a category that comprises specialized HEIs that provide training related to public services, such as the Philippine National Police Academy or the Philippine Military Academy, for example. There are presently 14 of these institutions.

Private HEIs

The vast majority – 88 percent – of HEIs in the Philippines, however, are privately owned. There were 1,710 private HEIs in operation in the 2016/17 academic year, which include both religiously affiliated institutions (mostly Catholic schools) and non-sectarian institutions. Most of these institutions offer the same type of tertiary education programs as public institutions and are overseen by CHED. A “Manual of Regulations for Private Higher Education [103]” details specific guidelines for private providers.

Many private HEIs in the Philippines are “demand-absorbing” institutions that fill a gap in supply created by the massification of education in the Philippines. Amidst limited capacities and low funding levels in the Philippine higher education system, these institutions offer those students who cannot get admitted into competitive public institutions access to tertiary education. It should be noted, however, that with the exception of top Catholic universities like Ateneo de Manila University, De La Salle University or the University of Santo Tomas, a majority [105] of these institutions are smaller for-profit providers that enroll fewer than 1,000 students. The quality of education at many of these profit-driven institutions tends to be below the standards of prestigious public HEIs.

Enrollment levels at public institutions therefore remain substantial, considering the large number of private HEIs. While the share of private sector enrollments in the Philippines is high by international standards, 45.8 percent of the country’s 3.5 million [106] tertiary students were enrolled in public institutions in the 2016/17 academic year. Just over 39 percent of students studied at state universities and colleges, 6.2 percent at local universities and colleges, and a small minority of 0.17 percent at other government schools. The largest university in the Philippines is presently the public Polytechnic University of the Philippines, which maintains branch campuses throughout the country.

Quality Assurance and Accreditation

The Philippine Commission on Higher Education (CHED) [65] has far-reaching authority over HEIs, including private institutions. It can authorize the establishment or closure of private HEIs, as well as determine their tuition fees and degree programs. Private HEIs are required to seek permission for their degree programs and to graduate students from these programs. Private institutions that have received this permission are authorized to display a “Special Order Number” (SON) on their academic records. The SON pertains to a specific credential awarded on a certain date and needs to be requested on a continual basis for batches of graduates.

However, CHED can exempt HEIs from the requirement to request SONs by declaring them “autonomous” or “deregulated” institutions – a designation that is granted for five-year periods and reserved for reputable high quality institutions. Autonomous institutions have the freedom to establish new degree programs and design their own curricula, whereas deregulated institutions still need to request permission for new degree programs, but are exempt from the special order requirements. CHED publishes lists of autonomous and deregulated universities on its website [108].

There is also a separate and voluntary accreditation process in the Philippines that allows HEIs to apply for accreditation of their programs by private accrediting bodies, such as the “Philippines Accrediting Association of Schools, Colleges and Universities” or the “Philippines Association of Colleges and Universities Commission on Accreditation”. Accreditation is mostly program-based and encouraged by CHED. The Commission incentivizes HEIs to seek accreditation by granting institutions with accredited programs a number of self-regulatory powers, such as financial and administrative autonomy, up to freedom to independently establish new graduate programs. There are four levels [109] of accreditation as set forth by CHED:

- Level I: Programs have undergone initial review and are accredited for three years.

- Level II: Programs have been re-accredited for three to five years, depending on the assessment of the accrediting body. This exempts institutions from applying for the SON, and allows them to redesign the curricula (within limits) and use the word “accredited” on publications.

- Level III: Programs have been re-accredited and fulfill a number of additional criteria, such as a strong research focus and high pass rates of graduates in licensing exams. This level gives HEIs the right to independently establish new programs associated with already existing level III programs.

- Level IV: Programs are considered to be of outstanding quality and prestige, as demonstrated by criteria like publications in research journals and international reputation. HEIs have full autonomy in running their accredited level IV programs and have the right to establish new graduate programs associated with existing level IV programs.

Given that accreditation is not a mandatory requirement, however, only a minority of HEI’s in the Philippines presently seek accreditation of their programs. In the 2016/17 academic year, there were 671 higher education institutions with accredited programs in the Philippines (about 28 percent of all institutions). CHED [110] provides an easy-to-navigate directory [111] of all the recognized higher education programs in the Philippines, organized by institution and region.

International University Rankings

Compared to other Southeast Asian countries like Thailand, Malaysia or Indonesia, the Philippines is currently not very well-represented in international university rankings. Only one Philippine university was among the 359 universities included in the 2018 Times Higher Education (THE) Asia University Rankings [112], while ten Thai universities, nine Malaysian universities and four Indonesian universities were included in the ranking. The University of the Philippines, arguably the most prestigious university in the Philippines, is currently ranked at position 601-800 out of 1,102 institutions in the THE world ranking. Four Philippine universities are included in the current QS World University Rankings [113]. These are: the University of the Philippines (367), Ateneo de Manila University (551-600), De La Salle University (701-750) and the University of Santo Tomas (801-1000). No Philippine universities are included in the current 2017 Shanghai ranking [114].

Enrollments by Type of Program and Field of Study

The vast majority of Filipino students are enrolled at the undergraduate level. Fully 89 percent were matriculated in bachelor-level programs and another 4.8 percent in pre-bachelor programs in the 2016/17 academic year. Graduate level enrollments are still small: Only 5.2 percent of students were enrolled in master’s programs and less than one percent in doctoral programs.

The most popular fields [115] of study in 2016/17 were business administration, education, engineering and technology, information and technology and medical studies. Of the more than 2.2 million students enrolled in these subject areas, about 41 percent chose business administration and almost 33 percent pursued education studies. Engineering, information technology and medical studies accounted for 20 percent, 18 percent and 9 percent, respectively.

University Admissions

Admission into university in the Philippines generally requires the high school diploma. Going forward this means the new K-12 diploma. CHED has announced [116] that beginning in the 2018/19 academic year, holders of the old 10-year high school diploma are expected to complete bridging courses before enrolling in undergraduate programs. In addition, more selective institutions have further requirements such as certain minimum GPA requirements, adequate scores in the National Achievement Test [117] (NAT) or institution-specific entrance examinations. There is no nation-wide university entrance exam as found in other Asian countries.

Degree Structure

Given the impact the U.S. had on the development of the modern Philippine education system, it is not surprising that tertiary benchmark credentials in the Philippines closely resemble the U.S. system. Higher education institutions also follow a two semester [118] system like in the U.S., however the academic year runs from June until March.

Associate Degree

Even though the Associate degree is not included in the Philippine Qualifications Framework, it is still awarded by several institutions in the Philippines. Associate programs are typically two years in length, although some older programs used to be three years in length. Associate programs often have a more vocationally-oriented focus, but also include a general education component and may be transferred into bachelor’s programs. Some institutions offer associate degrees as part of a laddered 2+2 system leading to a bachelor’s degree.

Bachelor’s Degree

Bachelor’s degree programs in standard academic disciplines are four years in length (a minimum of 124 credits, but most typically between 144-180 credits). The credentials awarded most frequently are the Bachelor of Science and the Bachelor of Arts. Bachelor’s programs in professional disciplines like engineering or architecture, on the other hand, are typically five years in length and have higher credit requirements. Programs include a sizeable general education core curriculum in addition to specialized subjects. Until recently, general education courses were typically completed in the first half of the program, while major-specific courses were mostly taken in higher semesters. The K-12 reforms, however, will lead to changes in curricula and likely reduce the general education component in bachelor’s programs.

Master’s Degree

Master’s programs require a bachelor’s degree for admission. Programs are typically two years in length (a minimum of 30 credits, but credit requirements vary from institution to institution). Depending on the discipline, master’s programs may include a thesis or be offered as non-thesis programs, with non-thesis programs usually requiring a higher number of credits and passing of a comprehensive examination.

Doctoral Degree

The doctoral degree is the highest degree in the Philippine education system. Doctoral programs require a master’s degree for admission and typically involve coursework and a dissertation, although some pure research programs without coursework also exist. The most commonly awarded credential is the Doctor of Philosophy. In addition, there are professional doctorates, such the Doctor Technology or the Doctor of Education. Most programs have a minimum length of three years, but students often take much longer to complete the program.

Professional Education

Professional degree programs in disciplines like medicine, dentistry, veterinary medicine or law are either post-graduate programs that require a bachelor’s degree for admission or long six-year first degree programs that involve two years of foundation studies after high school. While there are some variations in the programs offered, the general structure is as follows.

Law programs require a bachelor’s degree for admission, are usually four years in length, and conclude with the award of the Juris Doctor. Medical programs lead to the award of the Doctor of Medicine and require four years of study after the bachelor’s degree, including two years of clinical study. Graduate medical education in medical specialties involves a further three to six years of residency training after licensure.

Programs in dental and veterinary medicine, on the other hand, usually do not require a bachelor’s degree for admission. Instead, students are required to complete a two-year preliminary foundation program with a sizeable general education component before commencing professional studies. Students graduate with the Doctor of Dental Medicine or the Doctor of Veterinary Medicine after a total of six years of study.

In order to practice, graduates from professional programs must pass licensing examinations, the standards of which are set forth by a national Professional Regulation Commission [119]. This Commission regulates most professions and oversees more than 40 Professional Regulatory Boards that conduct the relevant licensing exams. Lawyers have to pass bar exams [120] administered by a Bar Examination Committee under the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court of the Philippines.

Teacher Education

The standard teaching credential in the Philippines is a four-year bachelor’s degree. Elementary school teachers earn a Bachelor of Elementary Education, whereas secondary school teachers earn a Bachelor of Secondary Education, with curricula being tailored to the respective level of education. Curricula are set by CHED and consist of general education subjects, education-related subjects, specialization subjects and practice teaching. Holders of bachelor’s degrees in other fields can earn a teacher qualification by completing a post-graduate program in education. These programs are between one semester and one year in length and lead to a credential most commonly referred to as the Certificate of Professional Education.

Grading Scales

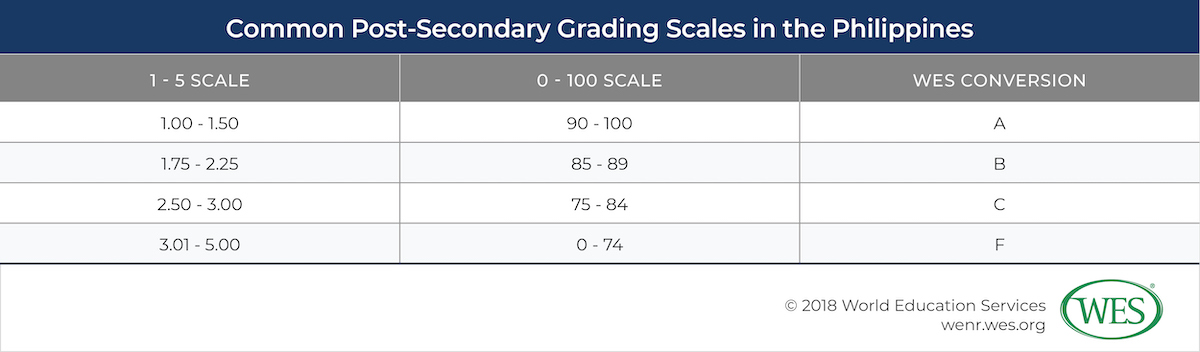

There is no standard grading scale [121] at the tertiary level that all institutions follow. It is more common for HEIs to use their own unique grading scales and include a legend or description of the scale on their academic transcripts. However, there are a few scales which are more common than others. The most common one is the 1-5 scale [122], with 1 being the highest grade. Also commonly used is a 0-100 scale with a minimum passing grade of 75.

Credit System

The credit system, on the other hand, is fairly standardized. One credit [124] unit usually represents at least 16 semester-hours of classroom instruction and most classes require three hours of in-class study per week. In a typical three-credit course, students, thus, attend classes for 48 hours per semester. In non-lecture based classes, such as labs or other practical courses, one credit is usually equivalent to 32 semester hours.

WES Documentation Requirements

Secondary Education

- Graduation Certificate/Diploma – submitted by the applicant

- Academic Transcript – sent directly by the institution attended

Higher Education

- Academic Transcript – sent directly by the institution (if study for one degree was completed at multiple institutions, the last institution attended sends a consolidated transcript)

- For completed doctoral degrees – a written statement confirming the award of the degree sent directly by the institution

Notable Documentation Peculiarities

All study reported on a single transcript: If a student completes study at multiple institutions, the courses taken by this student at different schools (subjects, credits and grades) are all included on the final transcript issued by the last institution attended. The institutions at which the student studied previously will not issue separate transcripts. To document study completed at multiple institutions, it is therefore sufficient to only request a consolidated transcript from the last institution attended (see the sample documents below for an example).

Recognition status of programs: Academic records issued by private institutions may provide cues about the official CHED recognition status of the program in question. The academic records will either indicate the mandatory special order number, or in the case of exempted institutions note their autonomous or deregulated status. If neither a special order number nor the autonomous/deregulated status is indicated on the documents, the program was either not completed, the special order number request is still pending with CHED, or the program is not recognized.

Sample Documents

Click here [125] for a PDF file of the academic documents referred to below.

- High school diploma and academic transcript (old system)

- High school diploma and academic transcript (K-12)

- National Certificate II

- Bachelor of Arts

- Bachelor of Science

- Master of Science

- Doctor of Philosophy

- Doctor of Medicine