Stefan Trines, Research Editor, WENR

Abstract: This education system profile provides an in-depth overview of the structure of India’s education system, its academic institutions, quality assurance mechanisms, and grading practices, as well as trends in outbound and inbound student mobility. To place current education reforms and mobility trends into context, we will first provide an overview of current socioeconomic developments in India and introduce some key facts about the country, before we outline mobility patterns and the education system.

Introduction: India in the 21st Century

India is a rapidly changing country in which inclusive, high-quality education is of utmost importance for its future prosperity. The country is currently in a youth bulge phase. It has the largest youth population in the world—a veritable army of 600 million young people [2] under the age of 25. Fully 28 percent of the population is less than 14 years of age, and with more than 30 babies being born every minute, population growth rates are expected to remain at around 1 percent for years. India is expected to overtake China as the largest country on earth by 2022 and grow to about 1.5 billion [3] people by 2030 (up from 1.34 billion in 2017). The UN projects that Delhi will become the largest city in the world with 37 million [4] people by 2028.

This demographic change could be a powerful engine of economic growth and development: If India manages to modernize and expand its education system, raise educational attainment levels, and provide skills to its youth, it could gain a significant competitive advantage over swiftly aging countries like China.

Some analysts consequently argue that India will eventually economically close in on China, because of India’s greater propensity for entrepreneurial innovation, and its young, technically skilled, rapidly growing English-speaking workforce—which is projected to be in increased global demand as labor costs in China rise faster than in India [5].

Indeed, India is now the world’s fastest growing major economy [6], outpacing China’s in terms of growth rates, even though it is still much smaller in overall size. Large parts of Indian society are simultaneously growing richer—the number of Indians in middle-income brackets is expected [7] to increase almost 10-fold within just two decades, from 50 million people in 2010 to 475 million people in 2030. Some analysts now predict that India will become the second-largest economy in the world by 2050 [8].

Islands of Prosperity in a Sea of Poverty: Constraints, Challenges and Uneven Development

At the same time, India is still a developing country of massive scale and home to the largest number of poor people in the world next to Nigeria. Consider that some 40 percent of India’s roads are still unpaved [9], while the country accounts for more than a quarter of all new tuberculosis infections worldwide—the disease kills more than 435,000 Indians [10] each year. India also has one of the highest mortality rates among children under the age of five worldwide, as well as one of the worst sanitation systems: 524 million [11] Indians did not use a toilet in 2017.

According to the World Bank, India succeeded in bringing 133 million people [12] out of poverty between 1994 and 2012, and extreme poverty continues to decline drastically [13]. However, India still has about a quarter of the world’s extreme poor [14], and social inequalities in the country are not only rampant but rising [15]. If current trends continue, India will be in danger of disintegrating into parallel societies with economic realities of elites in economic centers like Mumbai or Bangalore looking exceedingly different from those of the impoverished masses in underdeveloped states like Uttar Pradesh or Bihar. As economists Amartya Sen and Jean Drèze put it in a famous quote [16], India is looking “more and more like islands of California in a sea of sub-Saharan Africa.”

In light of such problems, it remains very much an open question whether India can harness its youth dividend to achieve inclusive economic development, or if it will become overburdened by population growth. As of now, India struggles to educate and employ its growing population: More than 27 percent [18] of the country’s youth are excluded from education, employment, or training, while the overwhelming majority [19] of working Indians are employed in the informal sector, many of them in agriculture, often in precarious engagements lacking any form of job security or labor protections.

It has been estimated that India’s economy needs to create 10 million new jobs [20] annually until 2030 to keep up with the growth of its working-age population—that’s more than 27,000 jobs each day for the next 12 years. While that’s not impossible—China reportedly created 13.14 million [21] new jobs in its cities in 2016—it’s certainly a tremendous challenge. Between 2013 and 2016 [22] India’s economy only generated an estimated 150,000 to 400,000 jobs each year. In one stark example of the dire labor market situation in present-day India, 2.3 million applicants applied for 368 open government positions in the state of Uttar Pradesh in 2015 [23].

India’s higher education system, meanwhile, does not have the capacity to achieve enrollment ratios anywhere close to those of other middle-income economies. The country’s tertiary gross enrollment rate is growing fast, but remains more than 20 percentage points below that of China or Brazil, despite the creation of large numbers of higher education institutions (HEIs) in recent years.

Educational attainment in present-day India is also not directly correlated to employment prospects—a fact that raises doubts about the quality and relevance of Indian education. Although estimates vary, there is little doubt that unemployment is high among university graduates—Indian authorities noted in 2017 that 60 percent of engineering graduates remain unemployed [24], while a 2013 study of 60,000 university graduates in different disciplines found that 47 percent [25] of them were unemployable in any skilled occupation. India’s overall youth unemployment rate, meanwhile, has remained stuck above 10 percent for the past decade [26].

Such bottlenecks have caused a large-scale outflow of labor migrants and international students from India: The number of Indian students enrolled in degree programs abroad has grown almost fivefold since 1998, while hundreds of thousands of labor migrants leave the country each year [27]. Many of these migrants are low-skilled workers, but there is also a pronounced brain drain of skilled professionals—950,000 Indian scientists and engineers [28] lived in the U.S. alone in 2013 (a steep increase of 85 percent since 2003).

Aside from cross-border outmigration, there is also tremendous internal migration: Rural poverty causes a staggering nine million people to relocate to India’s mushrooming cities annually. According to India’s latest census, there was a total of 139 million internal migrants [29] in the country in 2011.

The stakes for India in this situation are high. If the country fails to create meaningful job opportunities for its swelling youth cohorts, population growth could quickly turn toxic, exacerbating uncontrolled urbanization, overcrowding, pollution, and shortages of vital resources like drinking water.

This lack of opportunity, in turn, could stir up political radicalization and militant religious extremism—legions of idle and frustrated youths are easy prey for populist politicians playing religious identity politics [30]. The landslide election victory of hardline Hindu nationalist Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in 2014 indicates that Hindu nationalism has already become more palatable [31] in India—a trend that is also a defensive reaction to globalization [32], similar to the current developments in the United States.

Recent attempts by authorities to redefine diverse, multicultural India as a purely Hindu nation [33], spikes in mob killings [34] of Muslims, and increasingly zealous bans by Indian governments [35] on the slaughter of cows and the sale of beef—measures described as “dietary profiling [36]”—are all signs that religious Hindu extremism and anti-Muslim resentment could become growing problems in India.

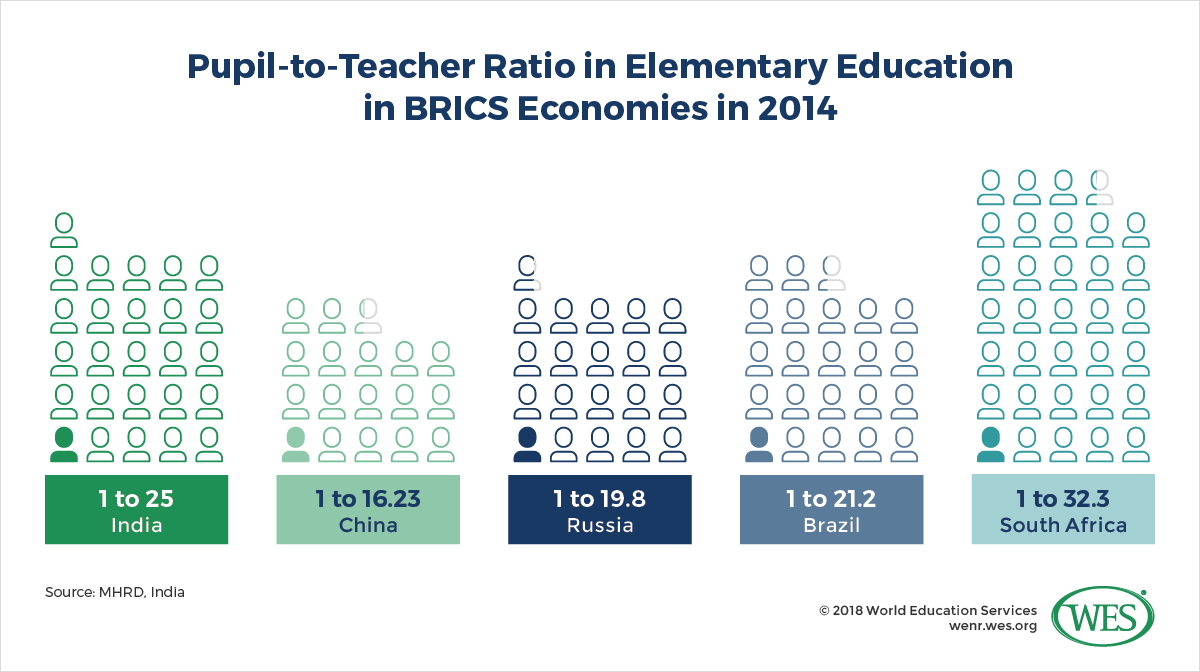

India’s social problems will magnify if the country does not provide more quality jobs, increase social mobility, and expand and improve its overburdened education system, which is weakened by inadequate funding and infrastructure, absenteeism among underpaid and poorly qualified teachers, high student-to-teacher ratios, academic corruption, and mounting problems of quality, particularly in India’s rapidly growing private higher education sector.

The Indian government rightly considers education the “… key catalyst for promoting socio-economic mobility in building an equitable and just society [37].” Gargantuan progress has been made in expanding access to growing segments of India’s society over the past decades, but providing relevant educational opportunities for a majority of the country’s burgeoning youth remains a pivotal challenge for Indian policy makers.

Incredible India: A Few Facts About a Highly Diverse Country With a Difficult Past

Modern India has been shaped by centuries of European imperialism and colonialism, most notably the formal colonial rule by Great Britain, which governed almost all of present-day India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh during the 19th century. Perhaps the most destructive aspect of that rule was the British sowed religious divisions by defining communities based on religious identity and divided the Indian subcontinent into administrative units along religious lines.

Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan (which then included present-day Bangladesh) were eventually granted independence in 1947 as separate sovereign countries—an event that was marred by horrific sectarian violence and mutual genocidal mass killings between Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs. An estimated 200,000 to two million people were killed; between 10 million and 20 million people fled and migrated between the newly created countries, or were forcefully displaced in one of the largest dislocations of people in modern history.

This tragedy was perhaps the most defining moment for contemporary South Asia. It antagonized Hindus and Muslims and placed India and Pakistan on a hostile footing ever since, resulting in three separate wars and a nuclear arms race between the two countries. The conflict over the disputed territory of Kashmir continues to be a constant source of tension and military confrontation today.

Of course, India remains a land of colossal proportions despite the partition. The country is, in a word, vast—it’s the world’s seventh-largest in terms of geographical area, stretching from the southern plains of Kerala and Tamil Nadu to the snow-capped Himalayas in the north. India borders Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, Myanmar, Nepal, and Pakistan and features some of highest mountains [38] on earth, the huge Thar Desert, 4,300 miles of coastline, and the famous and religiously important Ganges River. It has 36 states and territories, the largest of which are Uttar Pradesh [39] (home to an estimated 219 million people) and Maharashtra [40] (with approximately 119 million). To put it differently, India is a place where one individual state has more people than Pakistan or Nigeria, the world’s sixth and seventh largest countries in terms of population size.

Equally notable, there is tremendous ethnic, religious, and cultural variety across India’s states and territories. India’s constitution officially recognizes 1,108 castes [41] and more than 700 tribes [42] (formally called scheduled castes and tribes)—a degree of diversity that is mirrored by an astonishing assortment of languages that are spoken throughout the country.

While Hindi is the most widespread language, spoken as the mother tongue by 44 percent [43] of the population, India’s 1991 census counted 1,576 mother tongues [44] in total, with 184 of these languages spoken by more than 10,000 people [45]. In terms of religious affiliation, Hindus make up the majority—almost 80 percent [46]—of India’s population, but the country is also home to the world’s second-largest Muslim population after Indonesia—14.2 percent of the total population or about 172 million people identify as Muslims, as well as other religious minorities like Christians (2.3 percent), Sikhs (1.7 percent), Buddhists (0.7 percent), and Jains (0.4 percent).

Outbound Student Mobility

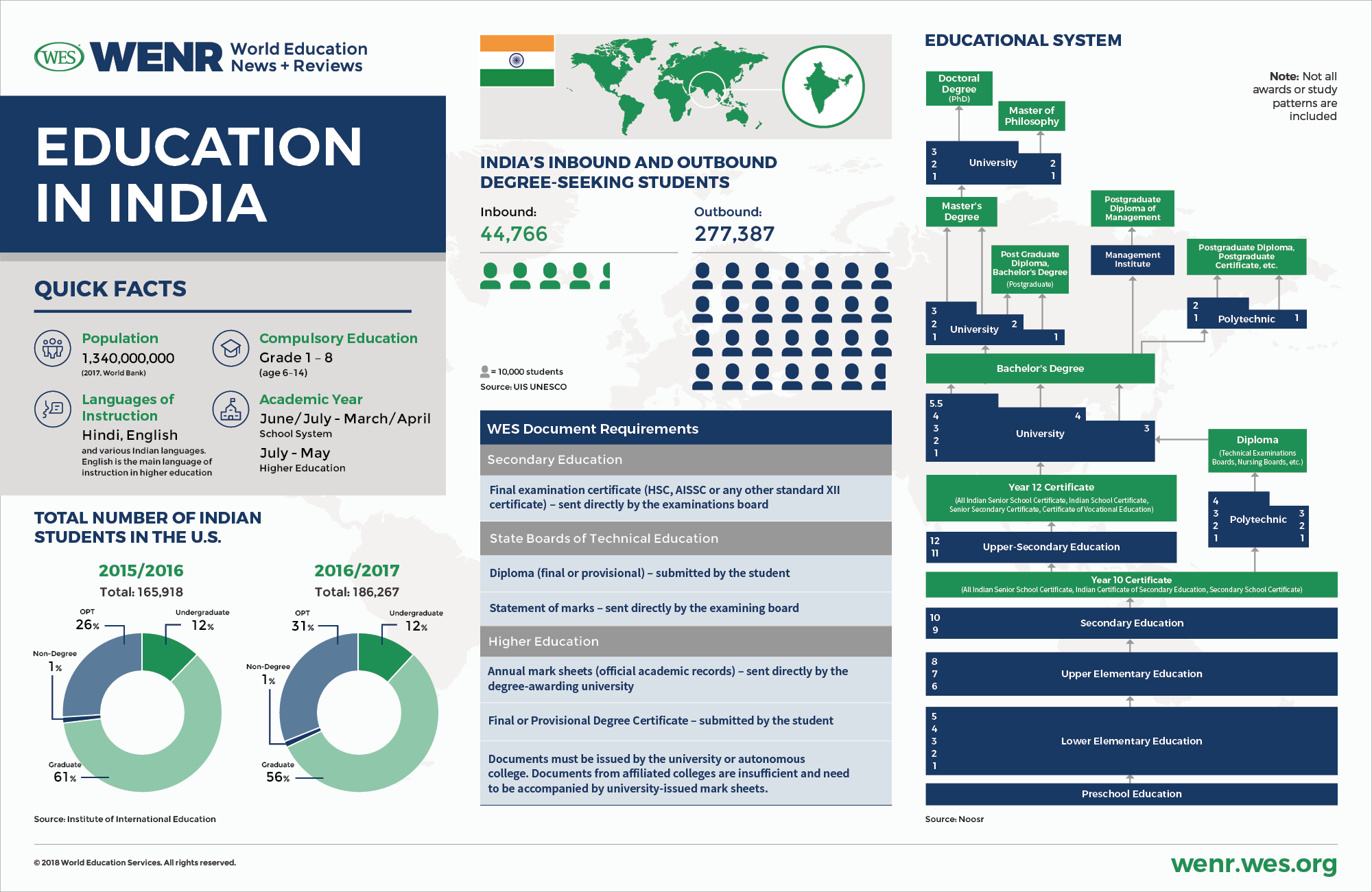

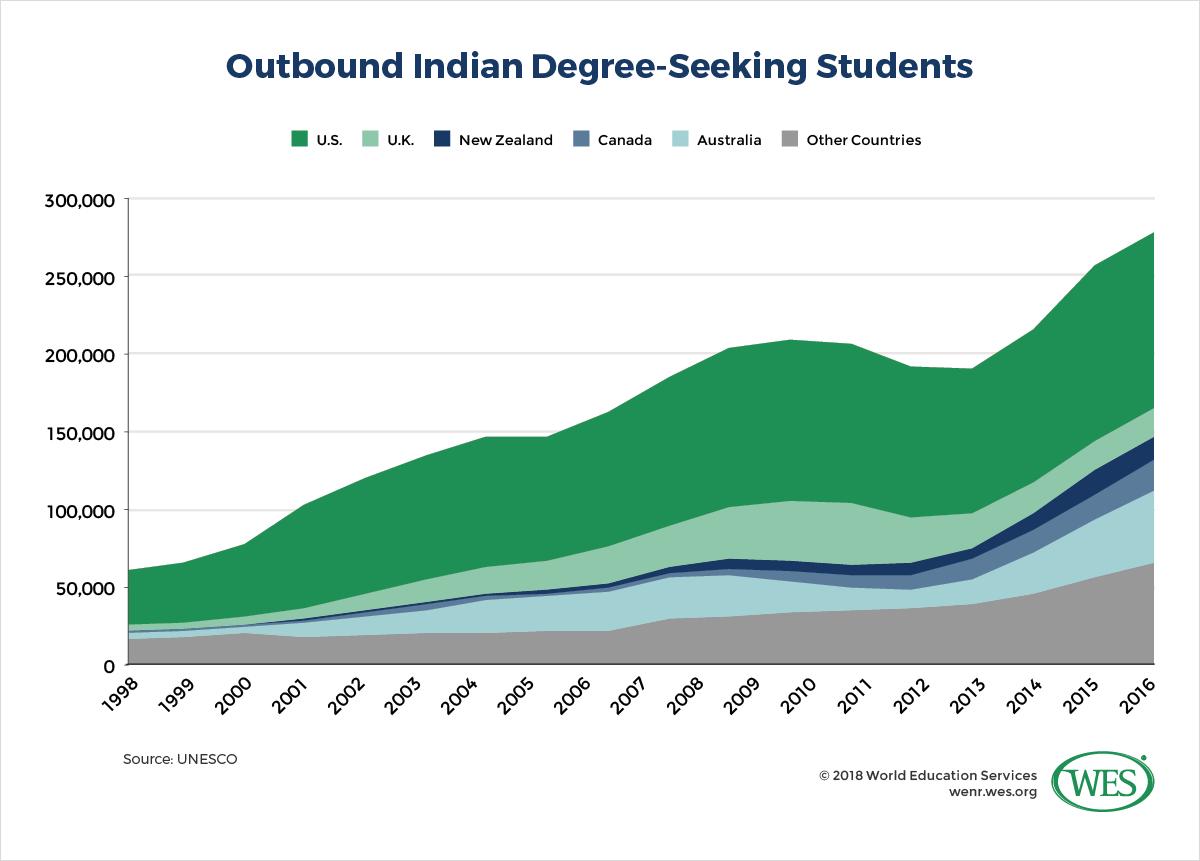

Student mobility trends in India are of great interest to university admissions personnel in the U.S., Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and increasingly in countries like Germany or China. India is currently the second-largest sending country of international students worldwide after China, and outbound student flows are surging. The number of Indian international students enrolled in degree programs abroad doubled from 134,880 students in 2004 to 278,383 in 2017, as per UNESCO [48].

Among these students, the U.S. is the most favored destination country by far, hosting 112,713 Indian students—40.5 percent of all outbound students in 2015. The second and third most popular study destinations are Australia, where numbers recently surged to 46,316 degree-seeking students, and Canada, which saw Indian enrollments almost quadruple from 5,868 in 2010 to 19,905 in 2016. In the UK, Indian enrollments have tanked by 53 percent since 2011, but the country is still the fourth-largest destination with 18,177 students in 2015. New Zealand, meanwhile, saw Indian enrollments explode by more than 500 percent since 2007 and became the fifth most popular destination with 15,016 students in 2016.

Notably, outbound mobility is not only growing, but also diversifying with Indian students increasingly branching out to countries beyond traditional English-speaking study destinations. The United Arab Emirates, for instance, has become the sixth-largest study destination with 13,370 students—a trend partially driven by the fact that Indian labor migrants now make up more than 25 percent [49] of the country’s resident population, while a number of Indian universities have set up branch campuses [50] in the Emirates. In Germany, the number of Indian students almost tripled to 9,896 within a decade and enrollments are growing briskly even in countries like Ukraine, which now hosts 4,773 students (up from 1,170 in 2006).

There is no UNESCO data available for China, but the country is an emerging destination [51] with strong growth rates. According to data provided by Project Atlas [52] of the Institute of International Education (IIE), there were 18,717 Indians studying in China as of 2017 (a sharp increase from 10,178 students in 2013). Note that these numbers, like other data cited below, are not directly comparable to UNESCO data, since they rely on a different method for counting international students.1 [53]

Future Growth Potential and Factors Affecting Outbound Student Mobility

Notwithstanding the high number of Indian international students around the globe, India actually has a very low outbound student mobility ratio of only 0.9 percent. Merely a tiny fraction of the country’s 36 million tertiary students is currently going abroad, which means that there’s enormous long-term potential for further growth. While overall momentum in outbound mobility is slowing in countries like aging China, where the quality of universities has matured and the benefit of a Western education for Chinese students has decreased [55], India’s burgeoning youth population will continue to face much more Darwinian challenges in securing access to quality education for years to come.

There is little question that a lack of access to high-quality education is a key driver of student mobility from India. Demand for education in the country is surging, yet unmet by supply—India will soon have the largest tertiary-age population in the world, but the tertiary gross enrollment rate (GER) stands at only 25.8 percent [56], despite the opening of ever-more HEIs. Large and growing numbers of aspiring youth remain locked out of the higher education system.

As of now, outbound mobility from India is still inhibited by the limited financial resources available to most students. WES research [57] by Rahul Choudaha, Li Chang and Paul Schulmann found that less than half of Indian students in the U.S. are financially independent and that more than two-thirds [58] seek some form of financial aid. The per capita income in India is growing, but presently stands at only USD$1,570 [59], which means that studying abroad in expensive foreign destinations remains out of reach for most Indians unless they obtain scholarships or other forms of financial assistance.

There is consequently a strong relationship between outbound student flows and macroeconomic conditions. Between 2011 and 2013, outbound students flows decreased drastically when India suffered a severe economic downturn and the Indian rupee depreciated by 44 percent [60] against the U.S. dollar, making it much more expensive for Indians to study abroad. Funding opportunities in the U.S. simultaneously dried up, so that many prospective international students waited out the crisis at home [61] — a trend clearly illustrated in the graph above.

Against this backdrop, current economic developments could throttle mobility from India, particularly to the United States. The Indian rupee has depreciated 10 percent [62] against the U.S. dollar since the beginning of the year, amid rising interest rates in the U.S. and concerns about a global trade war.

However, while such developments could presage downward fluctuations in the near term, they are unlikely to slow growth in the long run, given that India’s emergent middle class will gain greater purchasing power in the years ahead. As India’s Economic Times has noted [61], over “the past two decades, many first-generation Indians have risen up the corporate hierarchy and are financially well-off. These well-traveled, financially stable corporate executives desire the best for their children,” including a high-quality education.

Yet, while the number of people able to afford quality education is growing, top-notch learning opportunities are still in short supply and difficult to access in India. Many academic institutions are of lackluster quality and churn out graduates with poor employment and earning prospects—making a degree from a reputable foreign university a valuable asset in India’s competitive job market. Many Indian companies prefer to hire graduates [63] of foreign schools.

India’s engineering programs pump out some 1.5 million graduates [64] annually, but many of these alumni cannot find quality jobs—it is no coincidence that more than 70 percent [65] of Indian students in the U.S. are enrolled in STEM fields. WES surveys [66] of Indian graduate students in the U.S. found that many of them are disillusioned about their career opportunities at home; they are motivated to study abroad in order to improve their employment prospects in India.

Barriers to entering high-quality programs at top institutions like India’s Institutes of Technology (IITs), meanwhile, are so high that entrance requirements even at top U.S. universities are almost modest by comparison. The admissions rate at IITs has been below 2 percent [67] for years, while other prestigious institutions like the Christian Medical College, Vellore admitted a miniscule 0.25 percent [68] of applicants in 2015.

In another example, 374,520 applicants competed over 800 available seats in MBBS (Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery) programs at India’s top-rated All India Institute of Medical Sciences in 2018 [69]. Surveys of Indian students in China, where some 80 percent [70] of Indian international undergraduate students are enrolled in medical programs, found that the likelihood of being admitted was the most important motivating factor for China-bound Indian students [71]. Exploding costs for medical education at India’s private medical schools are another reason for the recent surge of Indian enrollments [72] in China.

High unemployment and cutthroat labor market competition in India also cause many Indian international students to use education as a springboard for employment and immigration abroad. Opportunities to work in the U.S. on optional practical training (OPT) extensions and H-1B visas, for instance, are a major draw for Indian students, as discussed in greater detail below.

In sum, social conditions in India are favorable for a further expansion of outbound mobility; it is almost certain that increasing numbers of Indians will flock to universities in foreign countries in coming years. While the tertiary enrollment rate in India is low, it is growing quickly—a key factor, since it usually increases the overall student population and with it the pool of potential international students. Rising prosperity among an emergent urban middle class will simultaneously make it easier for more Indians to afford studying abroad.

Trends in the United States

The number of Indian students in the U.S. has more than tripled since the beginning of the 21st century and grown rapidly as of recently. According to IIE’s Open Doors data [73], the number of Indian students reached its highest peak ever in 2016/17, when it spiked from 165,918 students in the previous academic year to 186,267 students—an increase of 12.3 percent.

However, it is highly unlikely that such growth rates can be sustained in the current political climate in the United States. Enrollments have already slipped—data on active student visas provided by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) show that the total number of student visas in the F and M category held by Indian students dropped by 0.27 percent [74] between December 2017 and March 2018, following a decrease of 28 percent [75] in new F-1 visas being issued to Indians in 2017.

This decline comes amid greater restrictions on H-1B work visas for highly skilled workers since 2017. Visa applicants now face greater scrutiny, processing times, and bureaucratic hurdles [76]. The DHS has greater leeway in limiting visa durations, and current proposals call for the termination of visa extensions—a measure that could affect hundreds of thousands of Indian workers [77]. The government is also considering barring dependent spouses of H-1B holders that applied for green cards from working in the United States [78], the vast majority [79] of them Indians. Computer programmers that hold associate degrees, meanwhile, are no longer eligible [80] for visas. Employers now have to provide much more detailed documentation and may face increased site inspections.

All of these measures have a chilling effect on employers—the number of new H-1B visa applications is declining [81], and some companies have begun to move jobs overseas [82]. The number of H-1B visas issued to Indians in the “initial employment” category dropped by 4.1 percent [83] between 2016 and 2017. Changes to OPT extensions for foreign graduates in STEM fields are also under consideration and OPT students already face greater restrictions on where they can work [84]—a change that coincides with companies hiring fewer [85] international students. Some observers have described the current policies as an attempt to force the “self-deportation [86]” of Indian tech workers, since Indians are disproportionately affected—slightly more than half [87] of all H-1B visas between 2001 and 2015 were given to Indian nationals.

These developments receive intense media coverage in India and will almost certainly affect the inflow of Indian students. It is relatively common for Indian students to work on OPT extensions and then apply for H-1B visas. According to Open Doors [88], 56.3 percent of Indian students are graduate students, while undergraduate students make up only 11.8 percent. A large majority, 71.6 percent, is enrolled in STEM fields, mostly engineering. India has the highest share (36.2 percent) of engineering students among the top 25 sending countries except for Iran. Notably, fully 30.7 percent of Indian students are currently on OPT. In other words, the most typical Indian student in the U.S. is a graduate student in a STEM field prone to pursue OPT.

These students are increasingly likely to seek study options in other countries as career pathways narrow in the United States. Indian news publications are filled with warnings about the “H-1B effect [89],” while Foreign Policy sees U.S. immigration policies heralding a “brain drain back to India [90].” The example of the UK is illuminating in this respect—many observers [91] consider restrictions on post-study work permits for international students, imposed in 2012 [92], a major factor behind the recent decline of Indian enrollments in the country. Student surveys have shown that a sizable number of international students considering the UK eventually chose another destination because of limited work opportunities [93]—a situation that caused the UK to ease restrictions again in 2017 for select countries [94], excluding India.

The reputation of the U.S. in India has recently also been harmed by a string of murders of Indian nationals, notably in Kansas City [95], that received great attention in the Indian media [96]. High profile hate crimes [97] against Indian students and rising U.S. ethno-nationalism have all helped to intensify concerns about physical safety among Indian students [97].

A Shift in Destinations: Trends in Canada

Countries like Canada, Australia, and Germany are increasingly benefitting from such developments and have experienced an accelerating inflow of Indian students, signaling a growing shift to other study destinations. In contrast to the U.S., Canada has over the past years increased the number of available immigrant visas for skilled workers in a variety of sectors, including fields of great interest to Indian students, such as software development or computer engineering [98]. Post-study work permits are relatively easy to obtain, and international students can apply for permanent residence [99] under Canada’s skills-based immigration system. In 2017, the Canadian government also made it easier for international students to apply for Canadian citizenship [100] after two years of permanent residence.

Add to that a large variety of study options at top-quality universities, lower tuition fees than in the U.S., Canada’s reputation as a welcoming, safe, and multicultural country, as well as thriving Indian immigrant communities in cities like Vancouver or Toronto, and it’s easy to see why Canada has become a highly attractive destination for Indian students. Per government data, the number of Indian students in Canada exploded by 962 percent over the past eight years, from 11,665 in 2009 to 123,940 [101]in 2017—a trend that resulted in India overtaking South Korea as the second-largest sending country of students after China.

Germany

Germany witnessed a similar surge, if on a smaller scale. The country is generally a good fit for Indian students because of its world-class engineering programs and—importantly—tuition-free education. Until recently, language barriers and limited post-study work opportunities kept Germany largely off the radar of Indian students. But Indian enrollments began to soar when German universities started to offer master’s programs in English, and the government in 2012 allowed foreign graduates to apply for the European Union “blue card”—a four-year work permit that gives holders access to labor markets throughout the EU and offers pathways to permanent residency. As a result, India in 2015 overtook Russia as the second-largest sending country of international students after China. Indian enrollments have since grown by another 31 percent to 15,308 students [102], making it well possible that Germany will soon overtake the UK as the leading European destination of Indian students, particularly since the impending Brexit could lock the UK out of the EU labor market.

New Zealand

In New Zealand, the rapid influx of Indian students in recent years was exceptional in that it was strongly driven by enrollments at smaller private providers rather than universities. After New Zealand’s government eased entry requirements for international students at these types of institutions in 2013, the number of Indian students more than doubled within just two years, from 7,036 in 2013 to 16,315 in 2015 [103]. Indian recruitment agents [104], some of them unscrupulous body merchants, were quick to capitalize on this development by channeling large numbers of Indian students to New Zealand—a development flanked by rising incidents of visa fraud [105], quality concerns, and reports of Indian students being exploited as cheap labor. As a result, authorities recently made it more difficult for international students to obtain work permits [106] and permanent residence. Visa regulations for foreign students were also tightened, with Indians experiencing the highest visa rejection rate [107] after Bangladeshis. Indian enrollments have since begun to drop [108], and it remains to be seen how attractive a destination New Zealand will remain for Indians in future years.

Australia

Australia is one of the fastest growing international student markets worldwide, shattering records each year [109]. The country draws Indian students with its high-quality institutions, great variety of programs in STEM and health fields taught in English, and opportunities for post-study work and immigration. Narayanan Ramaswamy, head of the education and skills division of KPMG India, told [110] the Economic Times in 2018 that the U.S. “has visa restrictions—it is not even sure whether they want more people. Australia, on the other hand, is sending out a clear message: We want more people who are hungry, who can contribute to the economy. It will be a big pull factor as far as Australia is concerned.”

As a result, the number of Indian students has more than tripled since 2004 and soared by 20 percent [111] between 2017 and 2018 alone. According to government statistics, there were 67,446 Indian students in the country in 2017 [112], making up the second-largest international student population after Chinese students.

That said, Australia’s government recently tightened visa regulations [113] for skilled foreign workers—a move that will disproportionately affect Indians [114]—and there’s a growing backlash [115] against immigration that could potentially help impede inbound student flows down the road. As current trends in Indian outbound mobility clearly illustrate, post-study work opportunities and immigration pathways are a draw for international students, whereas countries that erect barriers to such opportunities are becoming less popular.

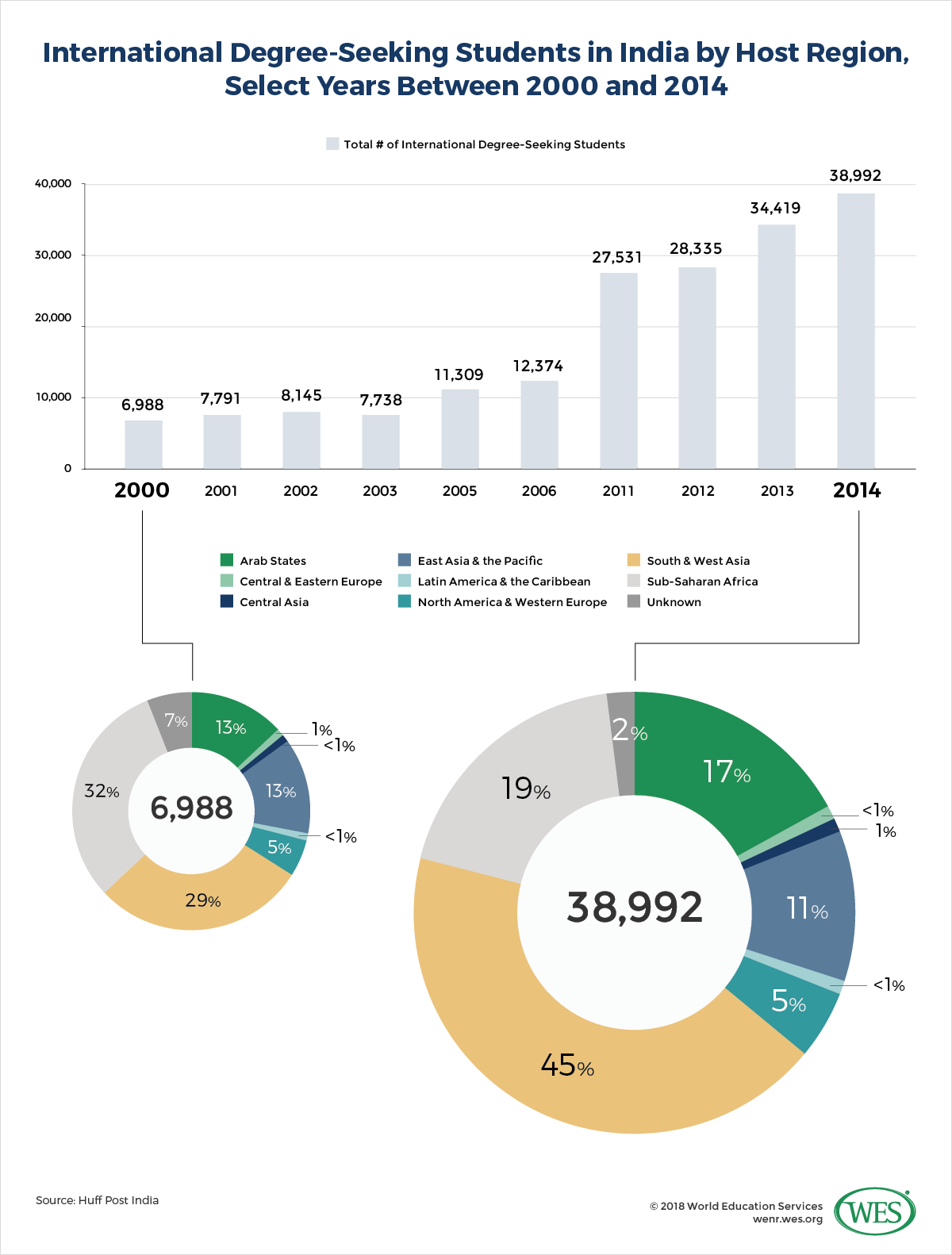

Inbound Student Mobility

India is not a major international study destination, but the country is currently seeking to attract more international students in order to internationalize and modernize its education system. In 2018, the government launched a Study in India campaign aimed at quadrupling the number of foreign students in the country to 200,000 by 2023 [116]. The initiative targets 35 recruitment markets [117], including a number of African countries, Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Malaysia, China, Thailand, and Vietnam, as well as other countries with sizable Indian populations of importance to Indian foreign relations.

To kick-start the initiative, India’s government will fund tuition waivers and promotion campaigns—15,000 university seats are allocated for foreign students for the 2018/19 academic year, 55 percent of which are eligible for fee waivers [118]. Bureaucratic hurdles have simultaneously been eased by granting autonomy to a larger number of universities, including the right to collaborate with foreign institutions featured among the top 500 in international university rankings, and to admit foreign students without prior government approval, up to 20 percent of the overall student body [119].

Given India’s tremendous size, the number of international students in India is still very small—the country has a minuscule inbound mobility rate of 0.1 percent [120], one of the lowest rates in the world. However, the number of foreign degree-seeking students as counted by UNESCO has grown by more than 60 percent since 2009 and stood at 44,766 in 2016, owing to enrollments from developing countries in South Asia and Africa, as well as Middle Eastern countries like Iran or Yemen.

According to the latest government data [56], there were 46,144 foreign students in the country in 2017/18; 25 percent of them come from neighboring Nepal. Aside from cultural and linguistic affinities and open borders between the two countries, students from impoverished Nepal are driven to India because of a severe lack of quality study options [122] in their home country—a fact that has also resulted in Indian distance education providers opening study centers in Nepal [123].2 [53]

Other large sending countries are war-scarred Afghanistan (9.5 percent of students), Sudan (4.8 percent), Bhutan (4.3 percent), Nigeria (4 percent), Bangladesh and Iran (3.4 percent each), and Yemen (3.2 percent). A large majority—77 percent—of foreign students are enrolled at the undergraduate level with engineering and technology-related majors, along with business administration, being the most popular. Enrollments in master’s and Ph.D. programs are still minor: Ethiopia was the largest sending country of students in Ph.D. programs with only 215 students. Most international students are concentrated in institutions in the tech hub of Bangalore, as well as in the state of Uttar Pradesh, bordering Nepal, and Maharashtra.

The heightened attempts by Indian authorities to boost inbound mobility demonstrate that India is still a long way from becoming an education hub of global scale. Compared with other Western and Asian international study destinations, India does not have the draw of a world-class education system. The country has other image problems as well, stemming from factors like a high degree of violence against women [124], poverty, and low standards of living.

Even top institutions like India’s Institutes of Technology have difficulty attracting foreign talent. The Indian government recently subsidized 10,000 seats [125] for foreign students at the IIT’s with tuition assistance, but only 31 students [126] sat for the institutes’ highly competitive entrance exams, held abroad in various countries in 2017, of which just seven were admitted. Most foreign students in India do not study at elite institutions, and most come from the least developed countries.

That said, the least developed countries are a recruitment market that represent tremendous potential, given their swelling youth populations and scarce educational opportunities. While India may have few top-quality institutions, it can offer students from such world regions a better education than they could access at home—in English and at much lower costs than in Western destinations. Many African students also view India as a coveted destination [127] for education in computer science and information technology. China is pushing into the same market [128], but India does have some advantages even over China, since most of its university programs are taught in English, and the country offers a more multicultural and open environment than China.

In Brief: India’s Education System

Education in India has an ancient tradition that dates back to the Vedic Period [129] (1500 to 500 BC). By the time European colonialists arrived, education mostly took place in traditional Hindu village schools called gurukuls, or in Muslim elementary and secondary schools called maktabs and madrasas [130]. The British colonialists then imposed an education system based on the British system and introduced English as a language of instruction. The first institutions of higher learning in a Western sense to emerge in British India were the University of Calcutta, the University of Bombay, and the University of Madras, all founded in 1857 [131] based on the model of British universities.

The British, sought to spread European science and literature and develop a loyal English-speaking workforce, recruited mainly from India’s upper classes, to administer its colony. They established education departments in the colony’s provinces and discriminately disbursed funds in favor of English language schools teaching British curricula [130]. On the eve of independence in 1947, India had 17 universities and about 636 colleges teaching approximately 238,000 students [131]. Undoubtedly, the British had altered the shape of education in India, but they left the country with a grossly unequal and elitist system—an estimated 80 percent to 90 percent of the population was illiterate [131] at the time of independence.

The period after independence was characterized by a rapid proliferation of teaching institutions across India as the country attempted to create a modern mass education system under the leadership of its first prime minister, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (in office from 1947 to 1964). India’s first constitution [132], adopted in 1950, called for the provision of free public and compulsory education for all children until the age of 14—an objective that still eludes the nation today, enormous progress in expanding access to education over the past 70 years notwithstanding.

India was established as a decentralized country with a federal system of government. Thus, India’s states emerged as strong actors after 1947 and autonomously administered most aspects of education in the decades after independence. However, the central government of the Indian Union began to incrementally assume greater responsibilities with the establishment of institutions like the federal Department of Education, the University Grants Commission (UGC), instituted in 1953, and the Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE), founded in 1962. In 1976, the constitution was eventually amended to make education the shared responsibility of the federal and state governments.

Administration of the Education System

While the role of the central government has since then expanded drastically, and central state planning has become the norm in the education sector, the administration of education in the heterogeneous country of India nevertheless remains complex and involves a variety of different actors with sometimes overlapping responsibilities. The system is politicized and characterized by diverging interests and turf battles between different agencies and bureaucracies at both the central and state levels [133].

As an advisory panel to the Indian government recently noted [134], “institutions and organizations have come up in a haphazard manner… [leaving India] stuck with a multiplicity of regulatory agencies and the challenge is to make them function in unison with one another.” Despite increased attempts to centralize education in recent years, persistent jurisdictional gray areas in the Indian system result in education-related policy decisions that are almost routinely contested in the courts.

The Republic of India, as it is officially called, is a federation of 29 states and seven union territories (as well as a number of small sub-state autonomous regions [135]). The composition of India’s states has changed considerably over the years – Telangana, India’s youngest state, was established as recently as 2014.

The federal government has exclusive control over matters like defense, foreign relations, trade, banking, or taxation; it directly administers most union territories through appointed administrators [136].3 [53]

The Indian states, on the other hand, have their own elected governments and have autonomy in clearly defined areas like policing, health care, and transportation. Education is constitutionally defined as a so-called concurrent [137] area of legislation, which means that it is the shared responsibility of the Union and the states. It is administered locally by the departments of education of the individual states, while the federal government sets overall policy objectives and guidelines at the national level.

The main federal body in the education sector is the Ministry of Human Resource Development (MHRD [138]), which oversees both school education and higher education through its Department of School Education and Literacy and its Department of Higher Education. Broadly speaking, the MHRD develops overall performance targets and reform initiatives for the entire system, and imposes or coordinates the implementation of these objectives with the governments of the states.

In the school system, the MHRD sets standards for teacher training [139] via the National Council for Teacher Education (NCTE [140]), while a separate body, the National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT [141]), coordinates the development of curricula and textbooks.

One of the main goals of federal agencies is to standardize education nationwide. For example, the Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE [142]), a federal examinations board under the purview of the MHRD, was set up in the early 1960s to provide uniform school education throughout India. However, since many Indian states created their own education boards, the CBSE is far from the only education board in India. But it is a highly influential and increasingly important standard-bearer nationwide. The number of schools affiliated with CBSE jumped from 309 in 1962 to 20,299 in 2018 [143], and the board continues to attract growing numbers of newly affiliated schools each year.

In addition, the MHRD oversees the National Institute of Open Schooling (NIOS [144]), an institution designed to provide schooling to underserved populations in remote areas via distance learning, as well as face-to-face instruction.

In higher education, the MHRD directly controls 47 central universities [145] and administers 91 institutions designated as Institutions of National Importance [146]. The ministry also oversees the UGC—a statutory body set up by federal legislation that is tasked with establishing and maintaining quality standards in tertiary education. The UGC approves and recognizes HEIs and disburses funds (grants) to these institutions.

Modeled after the now defunct British University Grants Committee, the UGC has been the main national quality assurance body in Indian tertiary education since its inception. However, the institution has in recent years been criticized for being overly bureaucratic and ineffective. In 2018, the Indian government introduced legislation [147] that will limit the role of the UGC to the administration of grants, while quality control will be shifted to a new body called the Higher Education Commission of India (HECI).

The main regulatory agency in technical and vocational education and training (TVET) is the All India Council for Technical Education (AICTE [148]) under the auspices of the MHRD. The AICTE is a statutory body tasked with accrediting academic programs and promoting quality and consistent standards in the post-secondary TVET sector. Given the growing importance of technical education in India, the AICTE has become an increasingly influential institution over the past decades.

In addition, there are several statutory bodies like the Medical Council of India, the Dental Council of India, and the Bar Council of India that regulate education in the professions.

Academic Calendar and Language of Instruction

Because of India’s widely varying climate, academic calendars deviate significantly in different states. However, the academic year runs mostly from June or July to March or April in the school system, and from July to May at universities. Traditionally, universities held annual examinations at the end of each academic year, but semester-based assessment systems are increasingly becoming the norm.

There is no single, nationwide language of instruction in the Indian school system, because of the country’s linguistic diversity. While Hindi and English are official languages in India, instruction in schools is conducted in a variety of local languages. India’s constitution recognizes 21 major languages [149] in addition to the literary language Sanskrit. They are Assamese, Bengali, Bodo, Dogri, Gujarati, Hindi, Kannada, Kashmiri, Konkani, Maithili, Malayalam, Manipuri, Marathi, Nepali, Oriya, Punjabi, Santhali, Sindhi, Tamil, Telugu, and Urdu. However, there are at least 47 different languages [150] used in schools throughout India. In the small multilingual state of Nagaland, for example, 17 different languages [150] are used in elementary education.

That said, Hindi is the most common medium of instruction and English is also becoming increasingly prominent, especially in private schools. According to the latest All India School Education Survey [151] by NCERT, Hindi is the medium of instruction at 51 percent of schools in India at the elementary and upper-secondary stages, whereas English is the language of instruction at about 15 percent and 33 percent of schools at the elementary and upper-secondary stages, respectively. Studies have shown that the number of children enrolled in English-medium schools increased by 274 percent [152] between 2003 and 2011 alone. In higher education, English is widely used in addition to Hindi and local languages.

The School System

With more than 1.5 million [153] schools and about 260 million [153] students in 2015/16, India has the world’s second-largest school system after China. Overall enrollment surges in recent years are attributable to the country’s youth bulge as well as increased access: Between 2010/11 and 2015/16, the student population in the school system grew by 5 percent or 12.6 million students, per government data [153].

Education in India is compulsory for all children from ages six to 14 and provided free of charge at public schools. Yet, despite tremendous advances in expanding access over the past decades, participation rates are still not universal, particularly in rural regions and among lower castes and other disadvantaged groups.

The overall net enrollment ratio (NER)—that is, the share of enrolled students within relevant age cohorts—is relatively high in grades one to five. It stood at 88.3 percent [154] in 2013/14 (up from 84.5 percent in 2005/06). However, participation rates dropped noticeably in grades six to eight, where the NER was only 70.2 percent. In lower-secondary education, the NER decreased further to 66.4 percent (as of 2013), while it was only 44.6 percent at the upper-secondary level per UNESCO [155]. In other words, India in 2013 had 47 million out-of-school children [156] that dropped out before grade 10.

Aside from troubling dropout rates, India’s school system remains plagued by problems like high teacher-to-student ratios, poorly educated teachers [157], and mediocre learning outcomes. While much of the available comparative data is somewhat dated, it demonstrates substantial weaknesses in India’s system. Mean years of schooling among the population above the age of 25, for instance, stood at only 5.4 years [158] in 2011 compared to more than 13 years in Western countries like the U.S., the UK, or Germany. The youth literacy rate, likewise, remained below the global average of 89.6 percent—it was 86.1 percent in 2011, according to the latest available UNESCO data [159].

When the Indian states of Tamil Nadu and Himachal Pradesh in 2009 participated for the first and only time in the OECD PISA exam, they scored second to last [161] among 74 participating countries and regions—a stark contrast to top-performing Asian countries like China or South Korea. Underscoring this weak performance, school surveys [162] conducted in 2016 by the non-governmental Pratham Education Foundation found that only 45.2 percent of Indian eighth-graders in rural schools were able to read simple English sentences, while merely 43.3 percent could perform three-digit division problems.

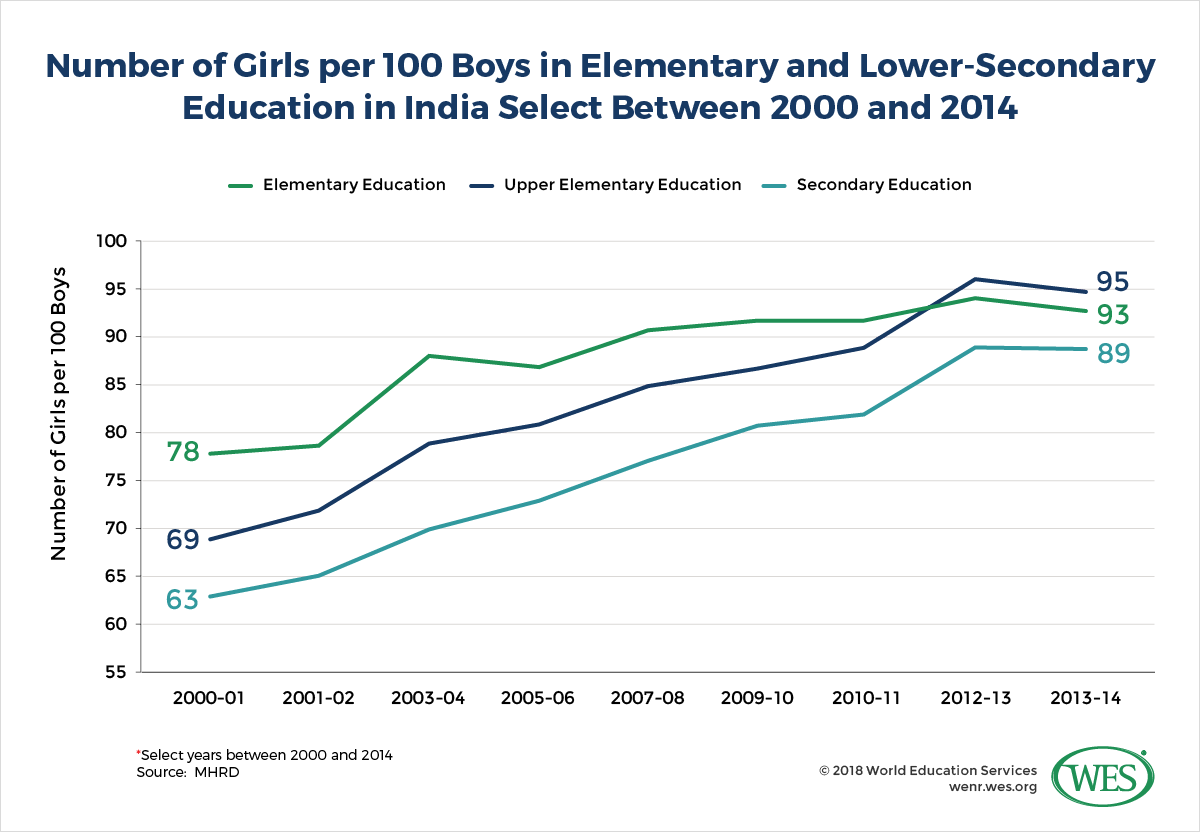

On the plus side, progress in female participation in education has been pronounced: Female literacy rates grew by 11 percent [154] between 2001 and 2011, and the gender parity index drastically improved at all levels of school education.

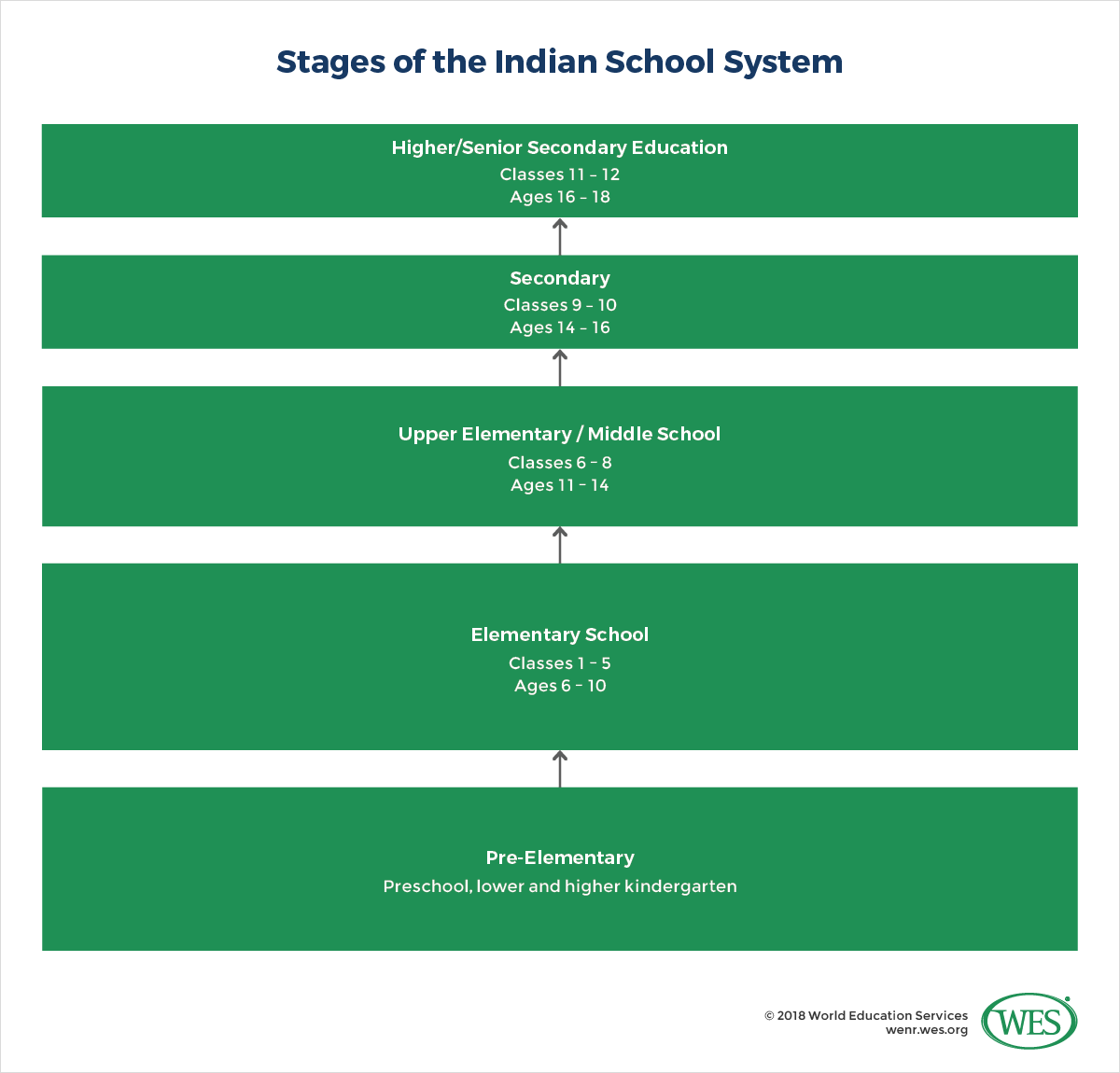

India also has made great progress in creating a more homogeneous education system. While the structure of education varied significantly between the different states and territories in the decades after independence, a new National Policy on Education [164], adopted in 1986, ushered in a much more uniform system. All states and territories now have what is labeled a “10+2” system, although minor variations in terms of structure still exist in some jurisdictions. This system comprises 10 years of general education: five years of elementary education, three years of upper-elementary education, and two years of secondary education, followed by an additional two years of more specialized upper-secondary education.

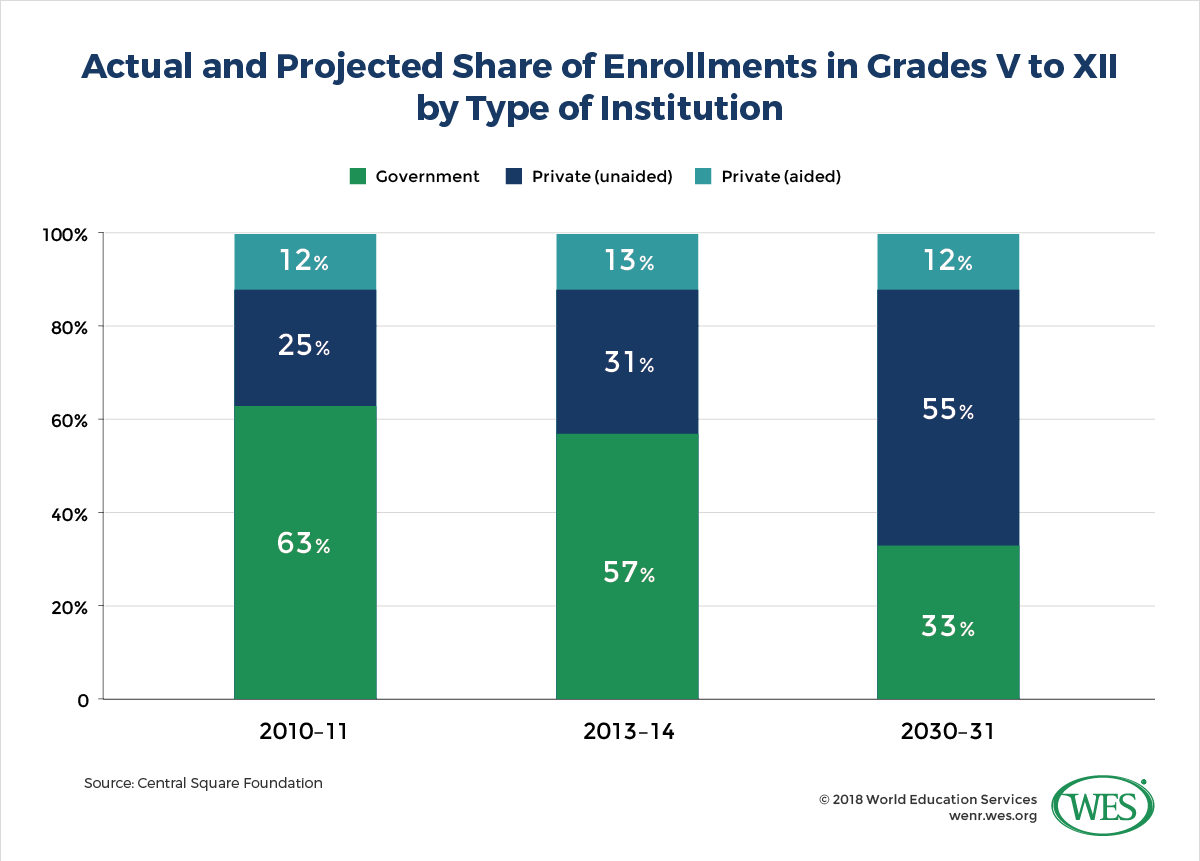

Education is provided by government-owned schools, fee-charging private schools, and so-called private-aided schools, which are privately managed schools that receive government grants and are mostly bound by the same curricular and administrative regulations as public schools.

Private schools are quickly growing in popularity, particularly in the cities. Between 2010/11 and 2014/15, enrollments in private schools increased by 16 million, while public school enrollments dropped by 11.1 million [166]. This distinct shift is a reflection of the declining state of India’s underfunded public schools, as well as growing interest in English-medium instruction, which is common in private schools.

Notably, this trend is not confined to expensive elite schools: Low-fee private schools are spreading rapidly and are expected to soon enroll 30 percent [167] of India’s students, particularly those from low-income households [168]. These schools are able to charge relatively modest tuition costs because they pay low salaries to their teachers. Many parents from low-income households now prefer these schools, which are often English-medium schools, over public institutions.

Increasing public distrust in government schools is also reflected in the rapid proliferation of unlicensed schools [166]. In 2009, India’s parliament passed legislation that requires all private schools to meet certain minimum standards and obtain formal authorization from government authorities—a bill called the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act. Yet, despite increased attempts by Indian authorities to clamp down on unlicensed schools, thousands of them continue to operate illegally in various parts of the country [169].

The fact that parents opt to send their children to unrecognized, fee-charging private schools even though study at these institutions opens much narrower pathways to further education is striking testimony to the scarcity of public schools in underserved areas and low public confidence in government schools.

As of now, most children in India still enroll in public schools, at least at lower levels of schooling. More than 65 percent of pupils in elementary grades, and about 58 percent of students in lower-secondary education were enrolled in public schools in 2016, according to UNESCO [48]. However, the majority of students in upper-secondary schools (59 percent) attended private institutions, and it is expected that a majority of students at all levels of schooling will soon be enrolled in private institutions.

To ensure conformity in learning outcomes in India’s heterogeneous school landscape, state and federal boards of education conduct external examinations at the end of grades 10 and 12; these exams serve as formal benchmark qualifications. Schools need to affiliate with one of these boards and teach curricula that prepare students for the external examinations. India also has a National Curriculum Framework [171] that seeks to harmonize curricula at public schools nationwide, even though only half of India’s states [172] had adopted the framework as of 2013. Students at unlicensed schools may sometimes be allowed [173] to sit for board examinations as external candidates, but face much more precarious [174] and uncertain prospects for further education.

Elementary Education

Compulsory education in India starts with grade one, with most pupils beginning their studies at the age of six. Before first grade, preschool education is provided by public community centers established under India’s Integrated Child Development Service initiative (ICDS [175]), as well as by private institutions. However, preschool education is not mandatory and is still uncommon in India—only 9.7 percent [154] of pupils attended preschool classes in 2013/14, despite UNICEF’s description of ICDS as the largest early childhood education program in the world [176].

Elementary education is divided into an initial five-year phase of elementary education (grades one to five) and three years of upper-elementary education (grades six to eight) in most states. The national curriculum [177] set forth by NCERT for the initial phase includes a local or regional language, mathematics, and the “art of healthy and productive living,” as well as environmental studies—an integrated subject including sciences and social sciences that is introduced as an additional subject in the third grade.

At the upper-elementary stage, pupils are expected to study three languages: their mother tongue, English, and a modern Indian language (typically Hindi or a different language in Hindi-speaking states). In addition, the curriculum includes mathematics, science and technology, social sciences, work education, arts, and physical education. The length of classes and the number of periods per week vary by state. Assessment and progression is usually based on periodic tests, other forms of school-based assessment, and annual year-end school examinations.

Secondary Education

Admission into secondary education (grades nine and 10), which is not compulsory, requires the completion of upper-elementary school. Education during this phase continues to be general with no or little specialization and usually includes the same subjects as in upper-elementary grades. That said, a number of technical schools and the National Institute of Open Schooling offer vocational courses at the lower secondary level. Students registered with the CBSE and some state boards can also elect a vocational subject [178] or “skills subject” in addition to the standard academic curriculum.4 [53]

There are year-end examinations in grades nine and 10; the state or federal boards of education conduct the final secondary school examination (see below). Recently the federal CBSE has sought to lessen the importance of examinations and foster a more holistic learning approach. In 2010 the board made sitting for external examinations in grade 10 optional, and introduced a school-based Continuous and Comprehensive Evaluation system. However, the reforms did not take hold and were tabled in 2017 [179], leading to the reintroduction [180] of external examinations. State boards, meanwhile, continued to hold external examinations throughout this period.

After passing the final examinations, students are awarded a certificate, the name of which varies between examination boards. Certificates awarded include the All India Secondary School Certificate, issued by the CBSE, the Indian Certificate of Secondary Education issued by the Council for the Indian School Certificate Examinations (CISCE), and the Secondary School Certificate (SSC) issued by state boards. Board examinations usually cover five or six subjects, including local and regional languages, Hindi, English, mathematics, science, and social sciences. In 2018, more than 1.6 million candidates sat for the CBSE grade 10 exams alone. The pass rate was 87 percent [181] compared with 90 percent in 2017.

Upper-Secondary Education

Upper or higher secondary education lasts two years (grades 11 and 12) and is more specialized and divided into streams. There are two different tracks: vocational/technical and general academic, with the latter being further divided into humanities, commerce, and science streams.

Admission into higher secondary education is competitive and usually based on the average score in the final grade 10 board exams. Minimum grades required for admission vary by stream and institution, but requirements are generally highest in the science stream. Delhi government schools, for instance, require an aggregate grade of 55 [182] for admission into the science stream compared with a score of 50 in the commerce stream. Humanities and vocational streams are open to all students who passed the secondary school examination, although a minimum score of 45 or 50 is required for certain subject combinations. Other schools require a minimum score of 60 [183] or higher in the science stream, and some may have additional entrance examinations.

Students who continue their education at the same school where they completed grade 10 may have more lenient admission requirements than external applicants, and might be allowed to enroll despite failing to meet standard requirements. CBSE students who opted for school-based assessment between 2010 and 2017 were expected to stay in CBSE-affiliated schools. Boards like the CISCE and the Maharashtra state board barred these students from admission into their affiliated schools [184].

The general academic track prepares students for higher education. Curricula are similar throughout India, but concrete subject requirements vary by examination board. As an example, the CBSE curriculum [185] includes two languages, one of which has to be English or Hindi; other compulsory subjects like general (foundation) studies, work experience, and physical education; and three elective subjects from the chosen stream. Available subjects in the humanities stream include political science, history, geography, economics, psychology, sociology, or languages. Common subjects in the commerce stream include accounting, business studies, management, or computer applications, while the science stream covers subjects like mathematics, physics, chemistry, biology, engineering, and computer science. It is uncommon for students to transfer between streams; students may have to repeat grade 11 in another stream if they wish to switch specializations midway.

The vocational track was created in the late 1980s [186] to foster skilled workforce development. It is designed to impart more applied education and prepare students for employment in specific vocations rather than higher education, even though graduates from the vocational track can also gain access to tertiary programs in related disciplines. In addition to mandatory language and general foundation subjects, students can choose from more than 150 vocational specializations offered by various boards throughout India in areas like agriculture, business, cosmetology, engineering, home science, or allied health (see here [187] for an overview of the courses offered by the CBSE).

Irrespective of the stream, there are internal school examinations at the end of grade 11 that students must pass in order to be promoted; and an external board examination at the end of grade 12, usually conducted in February each year. The final CBSE exams cover five subjects, including two mandatory language subjects (English, Hindi, or local languages), and three electives. Some subjects include a practical component, usually making up 30 percent of the examination.

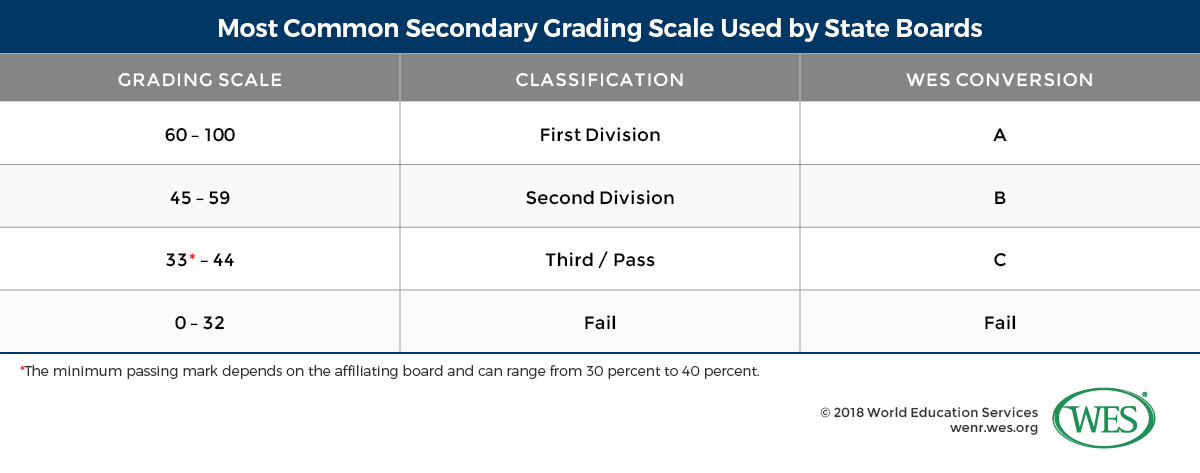

The exams are given in English and graded on a percentage basis. Candidates have to obtain at least 33 percent (out of 100) in five subjects to pass [188]. CBSE examination certificates also indicate a positional grade for each subject that indicates how well students scored compared to all students who took that subject in the same examination session. Students have three chances to pass the exams; they may also retake the exams the following year to improve their score.

CISCE by comparison requires English as a mandatory subject in addition to three to five electives. The medium of instruction at CISCE-affiliated schools is English and examinations are conducated in English as well. Candidates must pass four or more subjects with a score of 40 percent [189] to pass. In 2017, the CBSE pass rate was 82 percent [190], while 96.5 percent [191] of candidates passed the CISCE exams. Girls outperformed boys in both exams. Overall, approximately 14.4 million [192] candidates sat for standard 12 board examinations throughout India in 2017.

The final school-leaving credentials awarded upon passing of the board exams include the All India Senior Secondary School Certificate and the Delhi Senior School Certificate issued by CBSE, the Indian School Certificate issued by CISCE, and the Higher Secondary Certificate (HSC) issued by state boards. CISCE also awards the Certificate of Vocational Education to graduates from the vocational stream.

Secondary and Higher Secondary Education Boards

There are more than 50 different secondary and higher secondary education boards in India, many of them using considerably different curricula. Most states have their own board, and some states have more than one. Uttar Pradesh’s Board of High School and Intermediate Education is the oldest board in India and said to be the largest examining body in the world with 22,000 affiliated schools. In 2018, a total of 6.6 million candidates [194] sat for the board’s examinations at more than 8,500 testing centers throughout Uttar Pradesh. Other large state boards include the Maharashtra State Board of Secondary and Higher Secondary Education and the Bihar School Examination Board.

In addition to state boards, there are three national boards that conduct examinations beyond the confines of individual states:

- The federal CBSE, which gives the All India Senior School Certificate Examination for grades 10 and 12 and also conducts undergraduate entrance examinations in engineering and medicine. More than 20,000 schools throughout India are affiliated with CBSE; 1.1 million candidates [192] sat for its grade 12 examinations in 2017. CBSE also affiliates schools in several other countries [195], most of them schools in the Persian Gulf.

- The CISCE is a much smaller board with 2,161 affiliated schools [196] and about 260,000 test takers in 2018. CISCE is privately owned, but its Indian School Certificate is widely recognized by universities throughout India. Compared with other boards [197], it places greater emphasis on English with CISCE-affilited schools being required to teach in English.

- The federal National Institute of Open Schooling (NIOS) was set up by the MHRD in 1989 to provide education in underserved areas. NIOS allows students who have dropped out and others to study remotely on more flexible schedules. Students can sit for secondary and senior secondary examinations “on demand” at study centers when they feel ready. NIOS also offers a range of vocational and open basic education programs for children under 14. It currently has a student body of 7 million [198] and more than 6,000 affiliated study centers, including overseas centers in Bahrain, Kuwait, Nepal, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates.

Education boards usually develop curricula and text books, administer the examinations and oversee their affiliated schools. Affiliated schools can be public or private. The criteria for school affiliation differ by board, but schools are generally required to meet minimum requirements in terms of infrastructure (acceptable classrooms, sanitation facilities, libraries, Internet access, etc.), adequate teaching staff, and viable financial, organizational, and fee structures (a list of different state regulations can be found here [199]). Once affiliated, schools are expected to teach the prescribed curriculum and prepare students for the board exams.

International Schools

Demand for education in private international English-medium schools in India is soaring, if confined to wealthy households. Between 2012 and 2017, the number of English-medium international schools in the country increased from 313 to 469, while the number of students enrolled in these schools grew by 76 percent, from 151,900 to 268,500 [200] students. According to industry experts, the international school market in India is currently expanding at annual growth rates of 11 percent [201].

However, growth still remains constrained by the high tuition costs charged by international schools. While Indian nationals currently account for 75 percent of students in international schools that charge annual fees between USD$4,000 and USD$10,000, more expensive schools with fees above USD$10,000 mostly cater to expatriates with Indians making up only 43.5 percent [200] of students. That said, demand for these types of elite schools is likely to accelerate as India’s middle class expands.

Among the international curricula offered in India are the International Baccalaureate (IB) curriculum, currently taught at 152 official IB world schools [202], and the Cambridge International Examinations, which is the most ubiquitous curriculum and offered by more than 400 schools. The Indian Association of Universities (AIU) considers both the IB and the British Advanced Level [203] exams equivalent to an Indian grade 12 qualification; and many, but not all, Indian universities now accept these credentials for admission.

Technical Diplomas After Grade 10

In addition to secondary and higher examination boards, many states also have technical examination boards, examples of which include the Punjab State Board of Technical Education and Industrial Training or the Bihar State Board of Technical Education. These boards award diplomas in technical fields, such as the Diploma in Mechanical Engineering or the Diploma in Information Technology, credentials which are sometimes also conferred by universities and autonomous colleges.

In state-certified programs, teaching takes place at technical institutes and polytechnics affiliated with state boards, which set curricula and conduct examinations. However, overall quality assurance in technical education is centralized under the All India Council of Technical Education (AICTE), a federal body under the MHRD, which is tasked with setting training standards and approving new technical programs and institutions, including those seeking affiliation with state boards. Diploma credentials awarded by independent colleges not approved by the AICTE are not recognized as official academic qualifications in India.

As in other sectors of India’s education system, student enrollments in technical diploma programs have surged. The number of technical institutions offering diploma programs increased from 2,511 in 2006/07 to 4,037 in 2013/14, while the annual student intake nearly doubled, from to 634,000 to 1.17 million students [204]. More than 95 percent of these students were enrolled in engineering programs.

Most technical diploma programs last three years and straddle upper-secondary and higher education: Admission is usually based on the secondary school certificate or another standard grade 10 qualification. Minimum grades above 35 percent in mathematics and science and the passing of entrance examinations are frequently required as well. Under certain conditions, holders of the higher secondary certificate (HSC) or another standard grade 12 qualification who have studied adequate vocational-technical subjects may be allowed to enter laterally into the second year of the program.

Some diploma curricula may have a very small general education component (English and mathematics), but programs are generally specialized and major-specific. Some programs also include industry internships.

Graduates from diploma programs can get admitted directly into the second year of Bachelor of Engineering and Bachelor of Technology programs in related disciplines at higher education institutions. Usually, graduates also have the advantage of being able to circumvent the demanding entrance examinations of engineering programs, such as, for example, the highly competitive CBSE Joint Entrance Examination [205], required by all federally funded institutions. However, students may have to pass a lateral entrance examination [206].

While three-year 10+3 programs are most common, there are also a number of two-year 10+2 and four-year 10+4 programs in some fields, as well as 12+2 and 12+3 programs entered after grade 12. The latter include diplomas in disciplines like pharmacy or agricultural engineering.

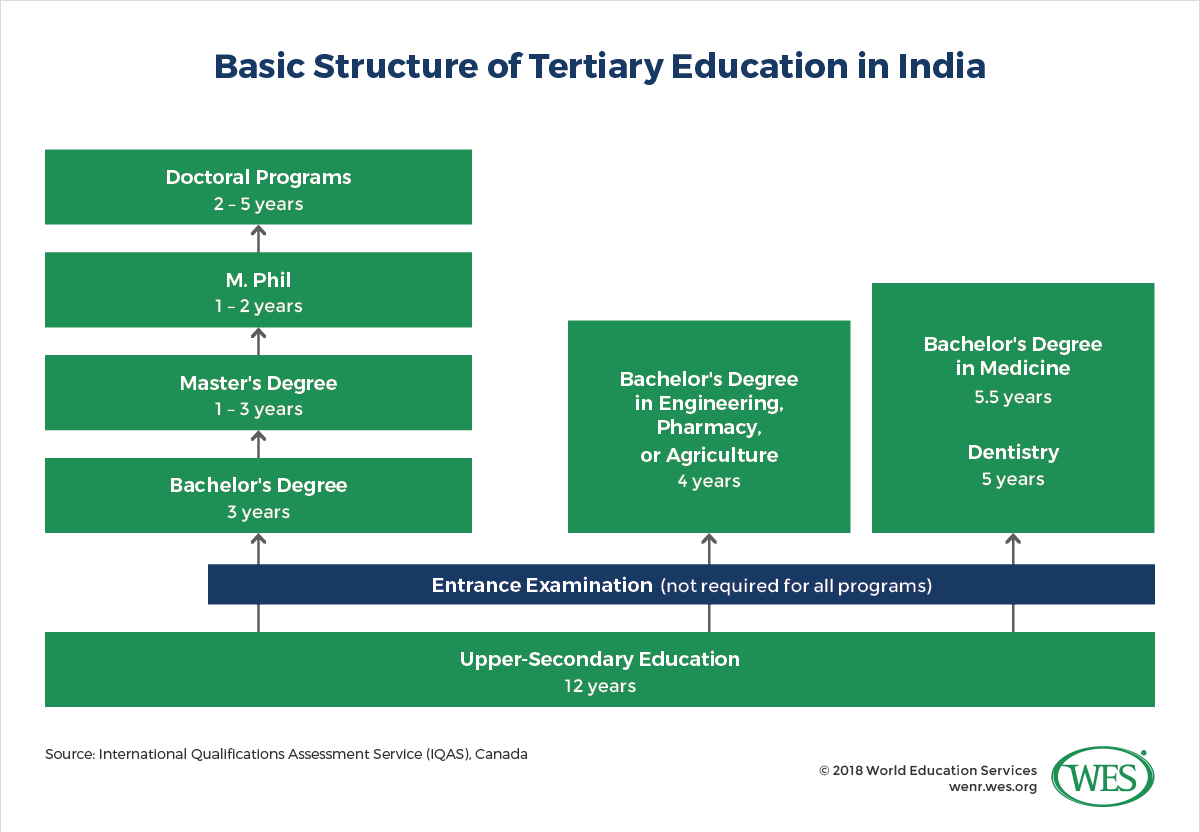

Higher Education

Rapid Growth amid Surging Demand

India’s higher education system has expanded drastically and undergone various changes since independence. India now has a much more socially inclusive mass-based education system than it did in the 20th century. Over the past two decades, the tertiary student population increased sixfold, from 5.7 million in 1996 to an estimated 36.6 million [56] in 2017/18. The number of universities, likewise, grew from 190 [207] in 1990/91 to 903 in 2017/18 [56], while the number of colleges exploded: 18,000 new colleges [208] were established between 2008 and 2016 alone—that’s more than six new colleges a day. The number of technical institutions offering programs at various levels jumped by a whopping 1,278 percent [209] between 1980 and 2012: While there were only 794 such institutions in 1980, that number is now higher than 10,000.

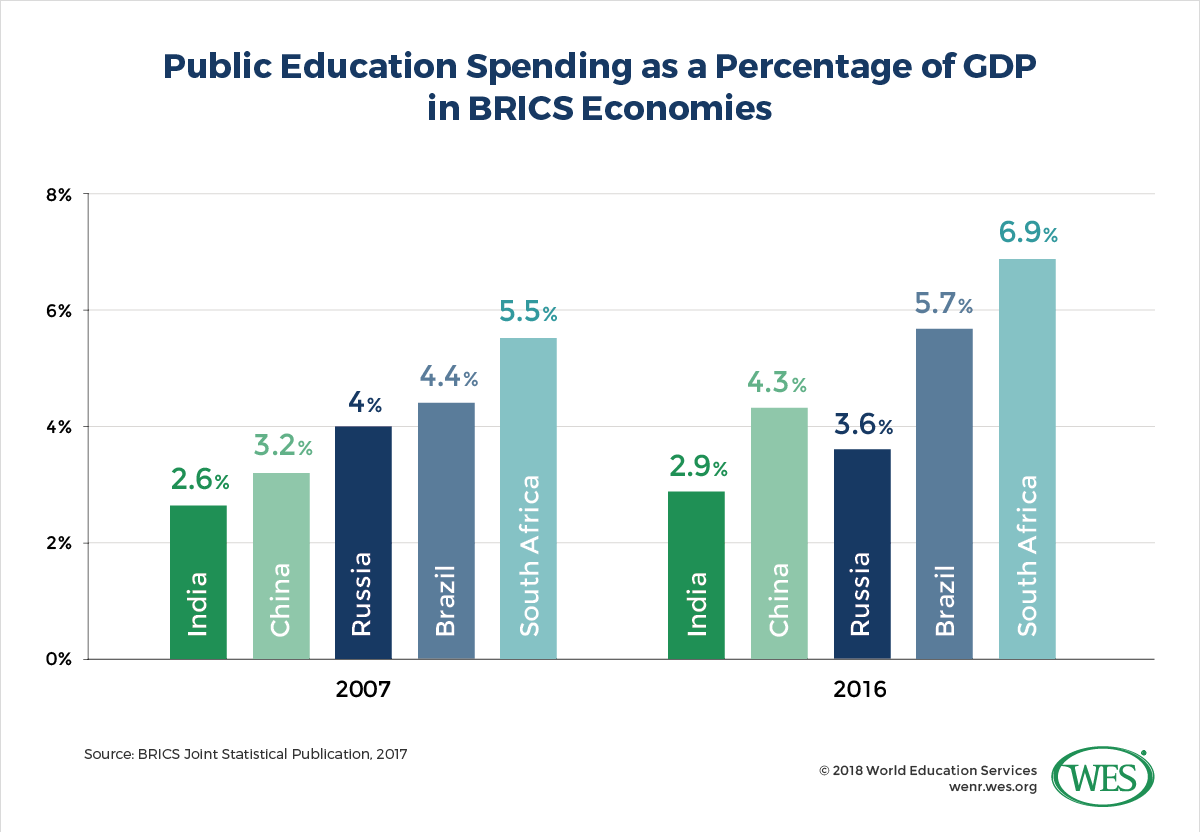

This massive expansion has greatly increased access to education, but has placed the Indian system under tremendous stress and so far failed to yield enrollment ratios comparable to those of other BRIC economies. India currently has a tertiary gross enrollment ratio (GER) of only 25.8 percent [56] (2017/18), compared with GERs of 50 percent, 48.4 percent, and 81.8 percent in Brazil, China, and Russia, respectively, according to the latest available UNESCO data [48]. India’s GER is well below the global average of 36.7 [210]percent, although it should be noted that its enrollment ratio is high compared with that of other lower middle income economies, which had a GER of 23.5 percent [48] on average in 2016.

The Indian government seeks to increase the GER to 30 percent by 2020, but the challenges in expanding access are enormous, given that the country is expected to soon harbor the largest tertiary-age population in the world. It has been estimated that more than 4 million additional university seats would have to be added within the next two years to reach the target GER of 30 percent.5 [53] Some projections on India’s needs are staggering: The India Brand Equity Foundation, for example, estimates that an additional 700 universities [211] and 35,000 colleges will need to be built to keep up with demographic trends in the years ahead. India also remains characterized by rampant disparities in access between its different states and territories. While the union territory of Chandigarh currently has a GER as high as 56.1 percent, that rate stands at only 14.4 percent [212] in the state of Bihar.

Drastic Expansion of Private Higher Education

Indian authorities have traditionally not held favorable views of private higher education, but fiscal exhaustion and mounting demand caused the Indian government to allow private HEIs to operate in India in the 1980s. Since then the private sector has grown drastically: While there were just 15 private universities in 2005, that number ballooned to 282 [213] in 2017. Between 2006/07 and 2011/12 alone, 115 private universities, 7,818 private colleges, and 3,581 private diploma institutions were established in India [214]. The majority of Indian students now study at private institutions: According to the MHRD, 77.8 percent [215] of Indian colleges are privately owned and enroll 67.3 percent of all students.

This growth has been driven by a variety of factors, including mounting public funding problems and a severe shortage of available seats at public institutions. In addition, students are attracted to the short-term diploma and certificate programs that private institutions [216] offer and that are more geared toward employment. However, unlike in the school system, where private institutions are often the preferred choice, most higher education students in private institutions would prefer to study at public institutions, according to nationwide surveys [217]. Because of factors like high costs and a generally low reputation of private higher education, most students [216] enroll in private institutions not by choice, but by necessity after failing to get admitted into a public HEI. Continued demand for public HEIs is also reflected in the growing numbers [218] of students securing private tutoring to prepare for these institutions’ entrance examinations.

Growth of Distance Education

India early on embraced distance education as a means to increase access to education, particularly in remote, underserved areas. In 1985, the federal government established the Indira Gandhi National Open University (IGNOU), an open distance education institution which is now considered the world’s largest mega university with more than three million [219] students. As this number demonstrates, distance education has spread dramatically in India since the 1980s. There are now 15 open universities in different states, while more than 200 additional HEIs, including many state and federal universities, are authorized to offer distance education programs by India’s Distance Education Bureau [220], which is the UGC’s quality assurance body for distance learning.

Distance education plays an important role in absorbing demand in India. Between 2006/07 and 2011/12 alone, the number of students enrolled in open and distance learning programs increased from 2.74 million to 4.2 million. At present, distance education accounts for 11 percent [56] of all higher education enrollments. It is a remarkable feature of India’s education system that the vast majority of students enrolled in undergraduate programs study remotely: According to MHRD data, 2.65 million [215] undergraduate students studied in distance mode in 2016/17, compared with only 1.75 million in regular programs.

Quality Problems

The rapid growth and massification of India’s higher education system has resulted in various quality problems, most notably in the fast-expanding private sector. As AICTE officials have noted, many of the newly established private colleges in India recruit “students using attractive websites and colorful brochures with glorified mission and vision statements [209],” but deliver substandard education. While there are a number of high-quality private HEIs in India, including, for example, the Birla Institute of Science and Technology (Pilani ) or the Manipal Academy of Higher Education, many private providers are small commercially oriented institutions that are run like businesses and place little emphasis on research—a fact often reflected in the retention of low-quality faculty [221].

Privatization also opened the door for the spread of unapproved fly-by-night providers. Just last year, the UGC and AICTE announced that 23 universities and 279 colleges were operating illegally [222] throughout India. Lists of such institutions are published on the websites of the UGC [223] and AICTE [224].

But quality problems are prevalent at public institutions as well. According to the government’s own assessment [214], the education sector “is plagued by a shortage of well-trained faculty, poor infrastructure and outdated and irrelevant curricula. The use of technology in higher education remains limited and standards of research and teaching at Indian universities are far below international standards with no Indian university featured in … rankings of the top 200 institutions globally.”

As mentioned before, sky-high unemployment among university graduates also reflects a lack of responsiveness to social needs and tends to undermine the relevance of education in India. In the latest 2018 U21 ranking [225] of higher education systems, India scored second to last among 50 countries. However, the performance of India’s education system also needs to be viewed in the context of its level of economic development. India scored 26th in the ranking when controlling for GDP per capita.

One issue of great concern for Indian authorities is the low research output of Indian universities. Recent research [226] found that the combined research output of 39 federally funded Indian universities, as measured in journal publications between 1990 and 2014, was less than that of either Cambridge or Stanford University alone — a weakness that observers have attributed to “unsuitable research infrastructure, inappropriate funding, highly bureaucratic systems of research funding, incompetent faculty members, lesser incentives for research and poor administrative structures [227]….”

That said, the research output of Indian institutions has recently improved, particularly in the discipline of chemistry [228], where India in 2014 was among the top 10 publishers of peer-reviewed articles worldwide. Likewise, four Indian medical colleges were among the top 10 institutions [229] that published the most research articles globally between 2004 and 2014. But recent increases in publications output are far from universal: 57 percent of India’s 579 medical institutions did not publish a single paper throughout the entire decade.

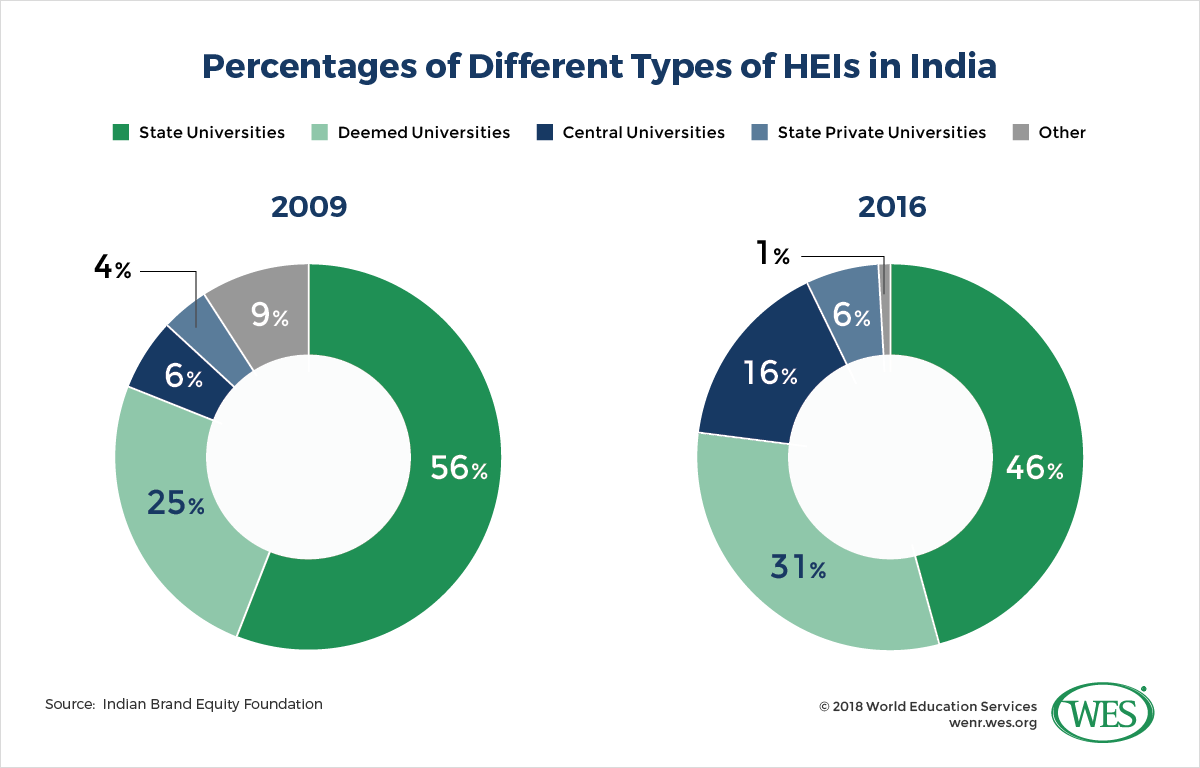

Types of Higher Education Institutions

Compared with other education systems, India’s has a large variety of HEIs. India’s UGC Act of 1956 specifies that only universities that were established by federal, state, or provincial legislation,6 [53] or institutions that have been granted the status of a deemed university by the federal government, are allowed to award academic degrees in India. Thus, there are five types of institutions with degree-granting authority: