Latest SEVIS Data: Number of International Students in the U.S. Is Declining

Stefan Trines, Research Editor, WENR

The latest data from the U.S. government’s Student and Exchange Visitor Information System (SEVIS) show that the number of active international student visas in the United States decreased by 0.84 percent between December 2017 and March 2018 – an acceleration over declines seen in the previous three quarters. SEVIS data is real-time data that includes student visas in the F and M category.

Released in April 2018 , the Department of Homeland Security’s new “SEVIS by the Numbers” report compares data from March 2017 and March 2018. It concludes that the number of active student visas declined by 0.5 percent over this entire one-year period, largely due to a 5 percent decline is the number of students in associate degree programs. (By contrast, the number of cultural exchange visitors on J-1 visas increased by 4 percent.)

The Department also provides more detailed data on its website (Mapping SEVIS by the Numbers). Comparing data from the last four months, it appears that the decline in student visas accelerated between December 2017 and March 2018. During that time period, the number of active visas decreased by 10,251, from 1,212,080 to 1,201,829.

The report reinforces earlier indications in the latest data from the Institute of International Education, based on a survey of approximately 3,000 accredited higher education institutions. Their Open Doors report showed a decrease in new international student enrollments of 3.3 percent in the 2016/17 academic year. Assessments by other organizations are similar – the National Science Foundation reported in January 2018 that international student enrollments in 2017 declined by 2.2 percent at the undergraduate level and 5.5 percent at the graduate level, respectively.

Some observers fear that the total drop in new international enrollments could reach 6 percent in 2018 (based on a preliminary IIE snapshot survey of 522 institutions from November 2017, which indicated a decline of 6.9 percent in new enrollments in the fall of 2017).

Many U.S. higher education institutions blame the anti-immigration rhetoric and policies of the Trump administration for the decline. The American Council on Education (ACE) and 32 other higher education associations, for instance, submitted an amicus brief to the U.S. Supreme Court when the court took up hearings on Trump’s latest travel ban in April 2018 that noted that the ban “sends a clarion message of exclusion to millions around the globe that America’s doors are no longer open to foreign students, scholars, lecturers, and researchers.” It “jeopardizes the vital contributions made by … [these individuals] by telling them in the starkest terms that America is no longer receptive to them.”

There are, of course, other factors that affect student flows to the United States, such as the cutting back of large-scale scholarship programs in key countries like Saudi Arabia, economic factors, and the growing attractiveness of competitor countries like Australia, Canada, and, increasingly, China.

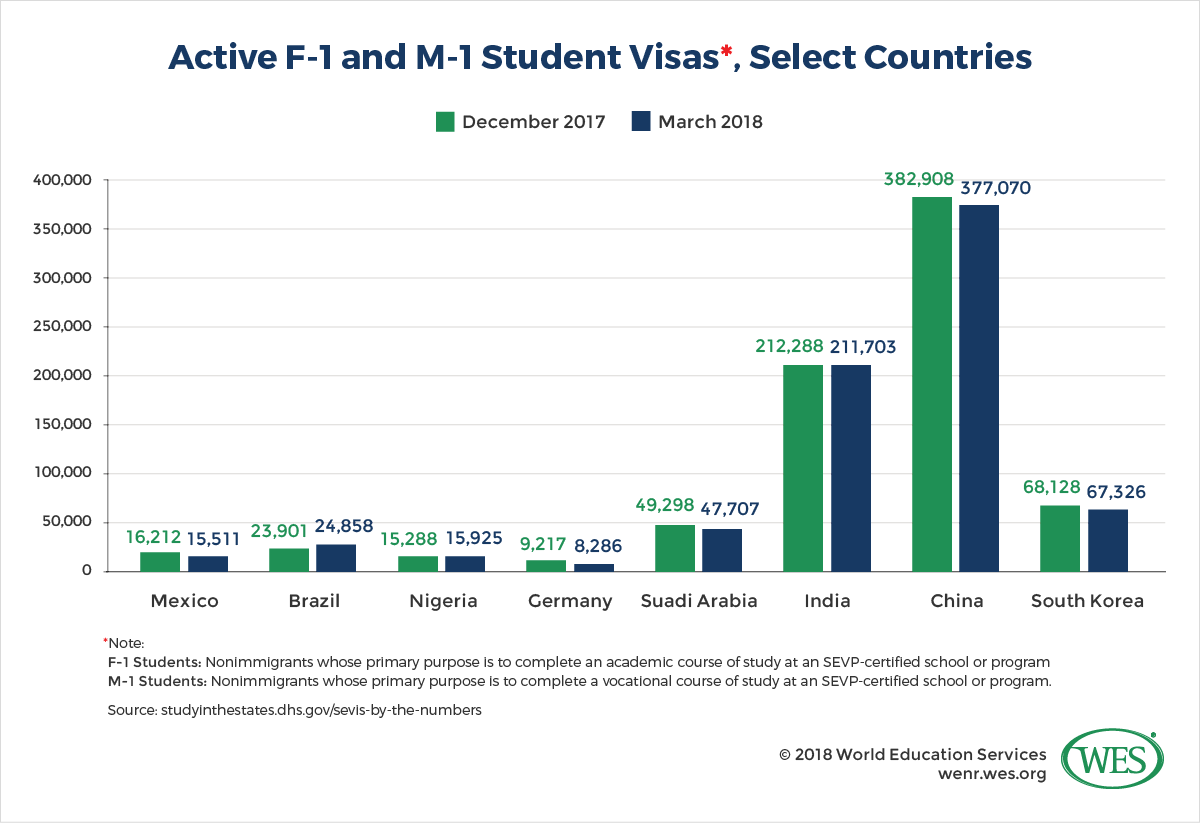

Whatever the reasons for the decline, the recent SEVIS numbers do not send positive signals for international student enrollments in 2018. While it is impossible to extract macro trends from data that extends over just four months, and there is always a certain degree of fluctuation, the SEVIS numbers reflect modest decreases in student enrollments since December 2017 from a large variety of sending countries, as well as sharp decreases from some countries like Germany, where the number of active students decreased by fully 10.1 percent.

At the same time, there are positive signs for enrollment trends from a number of countries. Here are some takeaways:

- The number of active students from China, the largest sending country by far, decreased by 1.5 percent from 382,908 to 377,070 students between December 2017 and March 2018. A full-blown trade war with China could further erode enrollments from China. Among the counter-measures China could take is limiting the inflow of Chinese students to the United States.

- Numbers from India, the second largest sending country, remained mostly stable (a slight decrease of 0.27 percent).

- The number of active students from Mexico decreased by 4.3 percent. Student flows from Mexico appear to be on a downward trajectory and favorability ratings of the U.S. in Mexico have plunged to their lowest point since the PEW Research Center started polling in Mexico. Open Doors data showed a small increase of 0.6 percent of Mexican students in the U.S. in 2016/17, but that data does not isolate new enrollments and is a far cry from the growth rates of previous years (20 percent between 2012/13 and 2014/15, per IIE data). SEVIS data shows that there currently are around 6,000 fewer Mexican students in the U.S. than three years ago (15,511 compared to 21,507 in February 2015).

- The number of active students from the countries included in the latest executive travel ban has thus far not fallen off a cliff. (Except for North Korea and Syria, F-1 and M-1 visas are exempted from the latest ban, but applicants may experience “enhanced vetting”). Student numbers from countries like North Korea, Somalia, and Chad are insignificant with enrollments far below 100. The number of active students from Libya, Syria, and Yemen decreased by 3.5 percent, 2.57 percent and 10.2 percent, respectively. The number of active students from Iran, the 11th largest sending country of international students to the U.S., however, remained mostly flat (-0.57 percent), while the number of active students from Venezuela, the 20th largest sending country of international students, decreased by 1.48 percent between December 2017 and March 2018.

- The number of active international students from Brazil, the 10th largest sender of foreign students to the U.S., increased by 4 percent, giving cause for optimism that outbound mobility from Brazil is rebounding after Brazil’s economic crisis and the phasing out of the “Science without Borders” scholarship program had slowed down student mobility in recent years.

- Numbers from other key sending countries also increased. The number of active students from Nigeria increased by 4.17 percent, while the number of students from Africa overall increased by almost 2 percent.

- Perhaps most troubling from the U.S. perspective are the declining numbers of students from Asian countries, specifically the lack of growth from this dynamic region. East Asia (including Korea, Taiwan, Japan, and Mongolia) decreased by 1.8 percent, while South East Asia (+0.2 percent) and South Asia (-0.18 percent) showed no growth on average. U.S. universities are highly dependent on students from Asia, which make up the overwhelming majority of foreign students on U.S. campuses. With China and other countries rapidly modernizing and internationalizing their education systems, U.S. universities may find it more difficult to compete in this region in the future.

In sum, there are some bright spots like Brazil or Nigeria and the overall picture is far from apocalyptic, but it is probable that student enrollments will decline throughout 2018 (and could possibly continue to decline further in the years ahead).

The recent slump in international student enrollments follows 16 years of spectacular growth – as recently as 2016/17, the number of international students in the U.S. reached a historic all-time high. Under the current circumstances, however, the question is no longer by how much will new international enrollments grow, but by how much will they decline and when will growth return?

The U.S. will remain the world’s leading destination for international students for the foreseeable future and growth may well return, but that position can no longer be simply taken for granted given the shrinking market share of the United States.

This outlook stands in stark contrast to the sky-high growth numbers in dynamic inbound markets like Australia, Canada, China or Germany. Australia just set a new record for international student enrollments. Foreign student enrollments increased by 13 percent between 2016 and 2017, compared to an average growth rate of 4.5 percent over the past decade.

The latest 2018 report released by the Canadian Bureau for International Education boasted a 20 percent increase in international student enrollments between 2016 and 2017 and an overall increase of 119 percent since 2010. The number of foreign students in China increased by more than 10 percent in 2017 an now amounts to 489,200 students, while the number of foreign students in Germany increased by 5.5 percent in 2017.