Education in Argentina

Carlos Monroy, Advanced Evaluation Specialist, WES

“What happened to Argentina?” is a question frequently asked by economists. At the beginning of the 20th century, Argentina was one of the ten richest countries in the world with higher per capita incomes than countries like France or Germany. Economic prosperity and seemingly boundless opportunities made the country a magnet for immigrants from Europe and Latin America. An estimated 7 million people migrated to Argentina between 1870 and 1930 alone, most of them from Italy and Spain. In 1914, Buenos Aires was a booming city with an immigrant population that made up more than 50 percent of the total population.

Since then, Argentina has time and again been viewed as a rising economic star, but has also experienced extensive periods of economic volatility thereby failing to live up to its full economic potential. The Economist has described Argentina’s economic performance over the past 100 years as “a century of decline.” Today, the South American country of 44.3 million is an upper middle-income economy ranked 58th among 191 countries worldwide in terms of GDP per capita in 2018 (trailing other Latin American countries like Panama and Uruguay).

Economic Problems

The reasons for Argentina’s economic problems are manifold – as Economist Rafael Di Tella has noted, “if a guy has been hit by 700,000 bullets, it’s hard to work out which one of them killed him”. One reason certainly is political instability. Throughout the 20th century, Argentina suffered from various military coups and dictatorships, until the country eventually entered a period of sustained democratization in 1983.

Democratization, however, did not stop Argentina’s economic woes. Factors like currency overvaluation, growing indebtedness, fiscal mismanagement, external shocks, and a sudden stop in capital inflows resulted in one of Argentina’s worst economic crises in 2001-2002. In what is the largest public insolvency in history, Argentina’s government in 2001 defaulted on its sovereign debt of USD $132 billion and lost access to global financial markets. The ramifications of the crisis were severe: between 1998 and 2002 economic output declined by 18 percent, reducing GDP per capita to levels last seen in the 1980s. The percentage of Argentinians living below the national poverty line rose from 25.9 percent in 1998 to 57.5 percent in 2002.

Since then, Argentina’s economic situation has improved markedly. According to the Center for Economic and Policy Research, the economy grew by 94 percent between 2002 and 2011, experiencing the fastest growth rate in the Western Hemisphere. The global financial crisis of 2008 slowed down economic growth and GDP contracted again between 2012 and 2014, but the present economic outlook is generally positive with Argentina’s economy being expected to grow over the coming years.

President Mauricio Macri, elected in 2015, settled outstanding debt obligations with hedge funds – a move that allowed Argentina in 2016 to rejoin the global financial markets that it had been locked out for 15 years. It should also be noted that despite its problems, Argentina remains one of the richest countries in South America with higher standards of living than in almost all countries on the continent. Along with Chile, Argentina is currently the only South American country ranked as having achieved “very high human development” on the UN Human Development Index.

Problems in the Education System and Education Reforms

Among the reasons cited for Argentina falling behind more dynamic economies like Singapore or South Korea over the past decades is a lack of technological innovation and the inefficiency of its education system. This is despite Argentina outperforming most countries in South America in a number of standard education indicators. Advancing access to education has historically been a priority of Argentine administrations – a National Education Finance Law passed in 2006, for instance, mandated that a minimum of 6 percent of the country’s GDP be spent on education. Education spending has since increased significantly, but spending levels still fall short of that goal. (Education spending stood at 5.87 percent of GDP in 2015, an average figure by regional standards).

Argentina’s literacy rate increased from 93.9 percent in 1980 to 98.1 percent 2015, and the country has the highest net enrollment rate in tertiary education in South America after Chile (UNESCO Institute of Statistics – UIS). In 2014, Argentina also had the second highest net enrollment rate in secondary education in all of Latin America (88.2 percent, according to the World Bank).

Despite these comparatively high enrollment ratios, however, Argentina’s education system produces far fewer university graduates as a percentage of the population than the systems in neighboring Brazil or Chile. A study from 2013 found that Argentina in 2010 had one of the highest tertiary dropout rates in the world. Only 27 percent of Argentinian students completed their studies, meaning that Argentina had a dropout rate of 73 percent, compared to 50 percent in Brazil, 41 percent in Chile and 39 percent in Mexico.

Statistics from Argentina’s Ministry of Education show that dropout rates are high at the secondary level as well and that many students do not graduate on time: 36.3 percent of the students enrolled in grade 10 in 2015 were above the official school age, and the dropout rates for grades nine, ten, and eleven were 9 percent, 12.5 percent and 8.6 percent, respectively.1

Argentinian students also perform poorly in comparative tests, such as the OECD PISA study. In 2012, Argentina ranked only 57th out of 64 countries participating in the study, behind Chile, Mexico, Uruguay, and Brazil.2 A World Bank analysis of Argentina’s learning outcomes found that there had been virtually no improvement in Argentina’s PISA performance between 2000 and 2012, while countries like Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru all made significant gains.

Given that Argentina is one of South America’s richest countries, Argentinian scholars have noted that problems like high dropout rates cannot be simply explained with socioeconomic factors like poverty, but are also owed to low student motivation and structural problems within the education system. Among the issues that have been raised are the decentralized and fragmented nature of the system and the fact that there is no nationwide secondary school leaving examination.

What is clear is that there are notable regional disparities in Argentina’s education system. As the eighth-largest land mass country in the world, Argentina is a big and culturally diverse country. There are significant differences between more rural provinces and urban centers like the city and province of Buenos Aires, where 43.4 percent of all elementary, secondary and non-university higher education students were enrolled in 2015. Argentina has a federal system of government, and the different provinces have far-reaching autonomy over educational matters. Regional disparities exist in terms of ease of access to education, quality of education, education budgets, infrastructure, or teacher salaries to name but a few examples.

These disparities are reflected in uneven educational outcomes in the different provinces. Government statistics show that ninth grade graduation rates, for instance, varied between 66 percent in the province of Neuquén and 88 percent in the province of La Rioja in 2015. Desertion rates in grade 12, likewise, ranged from eleven percent in Corrientes to 32 percent in Tierra del Fuego. In another example, the percentage of older students enrolled in grade eleven varied from 27 percent in Tucumán to 52 percent in Santa Cruz.

In recognition of these disparities, federal authorities have in recent years taken several steps to harmonize the different educational systems under the jurisdiction of the provincial governments. In 2006, for instance, a National Institute for Teacher Education (INFD) was established to develop a standard and coherent teacher training structure throughout the country. According to the Ministry of Education, the creation of the INFD has helped greatly to reform the previous “system of fragmented higher education institutions of unequal quality.”

Other harmonization measures included the standardization of academic qualifications by creating a “National Catalog of Titles and Certifications of Professional Technical Education” and a federal system of degrees and transcripts for most levels of education (excluding university education). The 2005 Vocational and Technical Education Law seeks to systematize training standards and quality assurance mechanisms in vocational education throughout the country. At the secondary level, the government is currently standardizing curricular streams nationwide – a reform that is expected to be completed by the end of 2019. Recent guidelines on compulsory education aim to decrease the dropout rates in secondary school and improve promotion and graduation rates throughout Argentina.

All of these reforms have helped to create a more homogeneous secondary and higher education system in Argentina than existed at the end of the 20th century. Standardizing education in the vast country nevertheless remains an ongoing challenge and disparities in access, quality and funding persist. Teachers, for instance, continue to protest disparities in salaries between different provinces and Argentina in 2017 and 2018 witnessed strikes and large-scale demonstrations organized by Teachers Unions.

Inbound International Student Mobility

While comparative student data on Argentina are scarce, Argentina is in all likelihood the country with the most international students in Latin America. According to government statistics, Argentina hosted 57,953 international students in the university sector alone in 2015 (excluding students enrolled at other post-secondary institutions). This compares to 19,855 foreign degree-seeking students in Brazil (2015) and 12,654 students in Mexico (2016), as per UIS data. (Note that student data reported by different organizations is difficult to compare).3

Over the past decade, international student enrollments in Argentina have doubled – mostly owed to the fact that the country has become a magnet for international students from other Latin American countries. Compared to more expensive destinations like Chile, Argentina offers Latin American students high-quality education at relatively low costs. As the British Council put it in a recent study, Argentina “has a well-established public higher education system with few fees (if any), no admissions exams and a globally respected level of quality. As such, it is not only a strong choice for those domestically but also for students regionally.” It should be noted that while undergraduate education at public universities is typically free, graduate programs usually incur tuition fees. More than 90 percent of foreign students study at the undergraduate level.

Political agreements like the MERCOSUR free trade agreement also make it relatively easy for Latin American students to obtain student visas in Argentina. Bet E. Wolff, Executive Director of the Argentine study abroad agency BEWNetwork, summarized the attractiveness of Argentina for foreign students as follows: “There are no entry exams, the level is acceptable and negotiable, it is free, you can live and work here with no restrictions, their currencies are stronger, there is no discrimination, and the night life is big fun.”

This competitive advantage, however, does not translate into high international enrollments from other world regions like Asia or Africa. While about a quarter of foreign degree-seeking students in Brazil come from sub-Saharan Africa (2015, UIS) and 30.9 percent of foreign students in Mexico come from Europe (2015/16), international student enrollments in Argentina are almost exclusively from Latin American countries (92 percent). According to data published by the Ministry of Education, Peru is the largest sending country with 10,543 students (2015), followed by Brazil (8,292 students), Colombia (7,124 students), Bolivia (6,170 students) and Paraguay (6,170 students). By contrast, only 3,563 international students came from European countries, 1,262 from the U.S., 794 from Asia, 275 from Africa and 78 from Oceania. Argentina’s flagship university, the Universidad de Buenos Aires, enrolls the largest share of foreign students.

The small percentage of foreign students from countries outside of South America may be a reflection of the somewhat limited emphasis Argentina places on the internationalization of its education system and the development of international partnerships and transnational education (TNE) programs. As in other Latin American countries, TNE in Argentina is growing, but still relatively narrow and hampered by legal constraints. While a number of foreign universities like Italy’s University of Bologna, for instance, have been allowed to offer education programs in Argentina, for-profit foreign education providers are barred from operating in Argentina. The current national education law explicitly bans for-profit higher education and stipulates that free trade agreements of which Argentina is part cannot include provisions that promote the commercialization of education in Argentina.

Outbound Student Mobility

Also indicative of the low priority given to internationalization, outbound student mobility in Argentina is small compared to that of other Latin American countries. Argentina had an outbound student mobility ratio (percentage of international students among all students) of only 0.3 percent in 2015 – a significantly lower rate than Brazil, Colombia, Chile or Mexico, for instance. Colombia, a country of comparable population size, currently sends more than three times as many degree-seeking students abroad than Argentina (28,763 students compared to 8,082 students in 2016).

Compared to the rapidly growing outflow of international students in many other countries, outbound mobility from Argentina is also relatively flat in total terms. The current number of Argentinian degree-seeking students abroad is lower than in 2007 and well beneath peak levels in years like 2010, when 9,835 Argentinians studied in other countries. High inflation and poor currency exchange rates for the Argentine currency make it expensive for Argentinian students to study abroad. The British Council forecasts student mobility from Argentina to decrease over the next seven years. It remains to be seen, however, how economic growth and the recent stabilization of exchange rates will affect outbound mobility from Argentina in the years ahead.

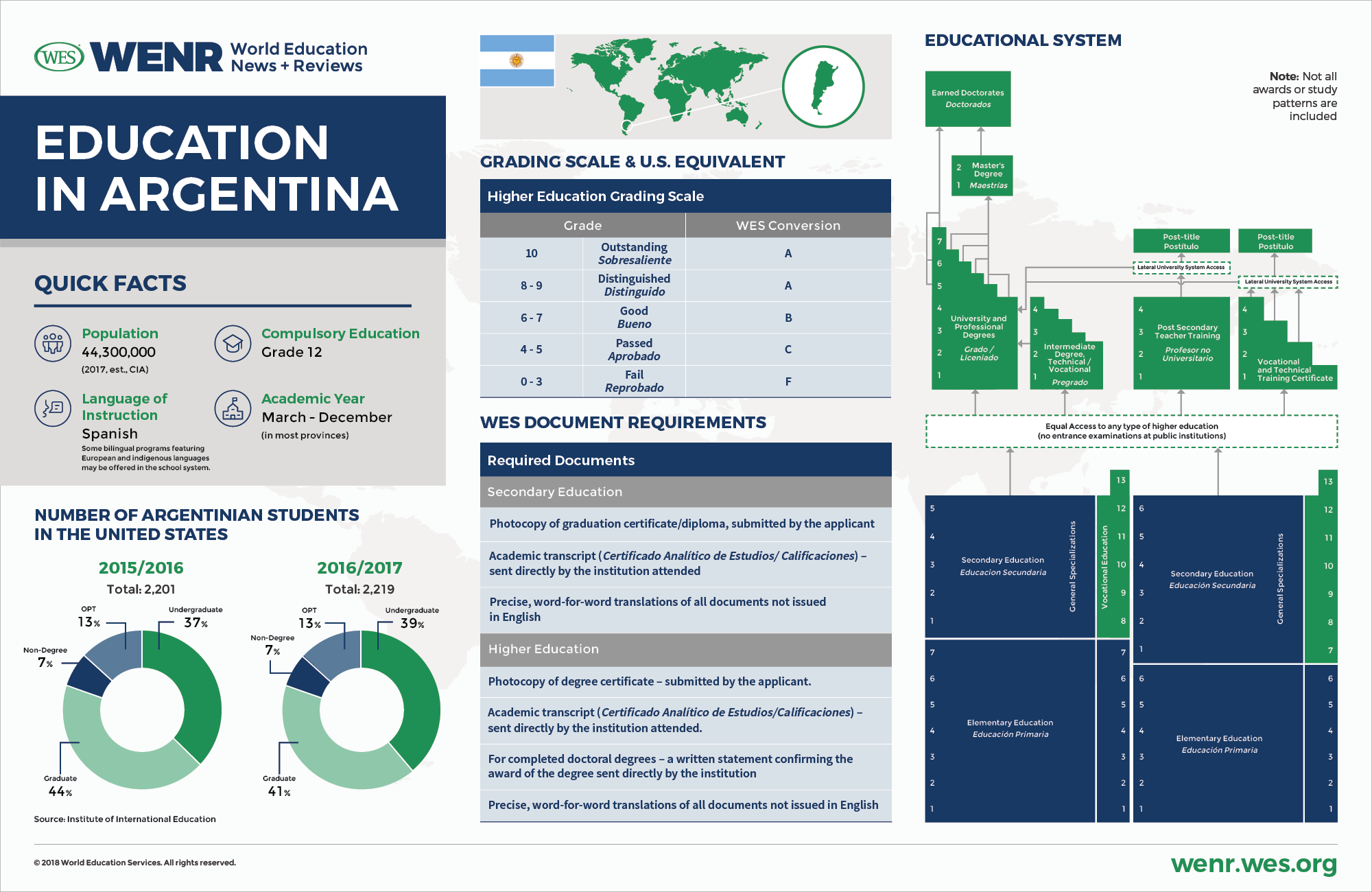

The U.S. is the most popular study destination of Argentinian students, followed by Brazil and the European countries Spain, France, Germany, and Italy. According to the Institute of International Education’s Open Doors report, 2,219 students from Argentina were enrolled in the U.S. in 2016/17 – an increase of 0.8 percent from the previous year, but below enrollment levels of 2007/08 when 2,535 Argentinian students studied in the United States. Argentinian students enroll in undergraduate and graduate programs in equal parts (39 percent studied at the undergraduate level, 41 percent at the graduate level, with the remainder pursuing OPT and non-degree programs in 2016/17).

In Brief: The Education System of Argentina

Administration of the Education System

Despite recent reform attempts to increase standardization, Argentina presently has one of the most decentralized education systems in Latin America. The country is constituted as a federation of 23 Provinces and the self-governing Autonomous City of Buenos Aires (24 jurisdictions in total). According to the current national education law, the federal government and the governments of the provinces and the autonomous city of Buenos Aires share responsibility for the “planning, organization, supervision and financing of national education in a joint, concurrent and agreed manner”. In concrete terms, this means that the Federal Education Council sets overall guidelines for elementary, secondary and vocational post-secondary (non-university) education, while the provincial governments retain formal jurisdiction over curricula, funding, planning and administrative policies.

The Argentine higher education system consists of two subsystems: the post-secondary non-university system (instituciones no universitarias/terciarias) and the tertiary university system (educación universitaria), which has a much higher degree of academic and institutional autonomy. While post-secondary/ non-university institutions operate primarily under the jurisdiction of the provinces, policy and quality assurance in the university sector falls under the Secretaría de Políticas Universitarias (Secretary of University Policies) under the federal Ministry of Education. The federal government finances most public universities (61) with the exception of five universities, which are funded by provincial governments.

Decentralization has created challenges and opportunities alike. Critics argue that decentralization is detrimental to quality and a reflection of efforts by the federal government to externalize costs in the wake of the fiscal crises of Argentina. Argentina used to have a highly centralized education system, but the federal government shifted various functions and responsibilities, including the funding of education, to the provinces between the 1960s and the late 1980s, in particular. Critics view this devolution as the main cause of current educational inequalities in Argentina and a failure of the national government to provide education of consistent quality throughout the country. On the other hand, Argentina’s fragmented system provides a wide diversity of post-secondary academic and vocational programs, some of which are uniquely related to the cultural riches and diversity of the individual provinces of Argentina.

Early Childhood Education

Since 2015, all Argentinian children are required to attend two years of early childhood education (Educación Inicial) at the age of four – an increase from previous years when children only had to complete one year of compulsory pre-school education. Current plans go even further and intend to make early childhood education compulsory from the age of 3 at the national level. Efforts are afoot to build 9,000 new classrooms across the country to accommodate this reform, which is estimated to extend early childhood education to an additional 180,000 children.

Elementary and Secondary Education

There are presently two different structural variations of school systems in place in the different provinces of Argentina. About half of the provinces have a 7+5 school system in which seven years of elementary education (educación primaria) are followed by five years of secondary education (educación secundaria). The remaining provinces have a 6+6 system consisting of six years of elementary education and six years of secondary education. Education is compulsory for all twelve years of schooling.

All provinces have their own education laws and ministries or departments of education and have formal jurisdiction over matters like grading practices, funding, quality assurance mechanisms, graduation policies, rights and obligations of students, teacher salaries and school calendars. However, the different provinces coordinate their policies in order to harmonize education systems at the national level. Provincial governments both provide input to, and follow overall guidelines from the Federal Education Council in terms of curricula, grading practices and other matters. All provinces are represented in the Federal Education Council.

Elementary Education

Elementary education starts at age six and lasts between six and seven years, depending on the province. Pupils study subjects like Spanish language, mathematics, sciences, social sciences, technology, art and physical education. Promotion is based on continuous classroom assessment and year-end exams. Upon completion of the program, pupils are awarded the Certificado de Educación Primaria (Primary Education Certificate).

Secondary Education

Secondary education is divided into two cycles: the Ciclo Básico (Basic Cycle) and the Ciclo Orientado (Orientation Cycle). The first cycle (Ciclo Básico) generally lasts until grade 9, while the second cycle (Ciclo Orientado) concludes with grade twelve. Admission is based on completion of elementary education and does not require separate entrance examinations. Promotion is based on school assessment – there are no external graduation examinations. Upon completion of the program, students receive the Título de Bachiller (Title of Bachelor), also referred to as Bachillerato.

The Ciclo Básico features a core curriculum taken by all students that includes subjects like Spanish, English, mathematics, sciences, social sciences, physical education, arts and technical education. The Ciclo Orientado, on the other hand, is divided into different academic streams in each province. Within these streams, students study different specialization subjects in addition to common core courses.

Until recently, there were a wide variety of different specialization streams offered throughout Argentina. However, current reforms seek to standardize the available streams to ten nationally approved streams (additional streams may be added in the provinces if approved by the Federal Education Council). In the autonomous city of Buenos Aires, for example, the reforms have already led to a consolidation of more than 150 available streams in 2012 (with a multitude of specializations ranging from pedagogy to information technology or hydraulics) to 13 streams in 2017.

All provinces of Argentina are expected to fully implement new curricula in compliance with national guidelines and offer at least the ten main streams set forward by the Federal Education Council by 2019. The ten nationally approved streams are: Physical Education, Arts, Agriculture and Environment, Social Sciences and Humanities, Natural Sciences, Economics and Administration, Tourism, Information Technology, Languages and Communication.4

Most Argentinian students attend public schools, even though 26.5 percent of secondary students were enrolled in private schools in 2015 (UIS). Many private institutions are run by the Catholic Church, but there are also a number of secular secondary schools and international schools teaching foreign curricula that lead to qualifications like the International Baccalaureate or the British International General Certificate of Secondary Education.

Secondary Vocational and Technical Education (Educación Técnico Profesional)

Outside of the general academic specialization tracks, students have the option to alternatively enroll in more vocationally oriented programs. These programs are entered after completion of elementary education and last six or seven years, depending on the program (i.e. a combined total of 12 or 13 years of schooling). Curricula are usually structured into an initial three-year general education component (Ciclo Básico) followed by three or four years of employment-geared education in specific vocations. Some programs include practical internships in related industries. The programs lead to the award of the Título de Técnico (Title of Technician) – a credential that gives access to tertiary education.

There are a wide variety of vocational programs available in Argentina. According to Argentina’s National Institute of Technological Education, there were as many as 2,608 programs offered in 2014. The most popular specializations as of recently (2011) were electro-mechanics, farming, construction, computer science, business, electronics, and process industries.

In an attempt to standardize vocational education, the national government has established more restrictive guidelines for the provinces in a 2005 Vocational Education Law (Ley de Educación Técnico Profesional) and created a ‘National Catalog of Titles and Certifications of Professional Technical Education’ (Catálogo Nacional de Títulos y Certificaciones de Educación Técnico Profesional). The catalog categorizes secondary vocational programs into 27 fields of study with additional sub-divisions. More recently, the Federal Council on Education has drawn up concrete curricular guidelines in specific fields, such as agriculture, construction, computer science and nursing to name a few examples.

The Argentine government generally seeks to strengthen “technical education and professional training promoting its modernization and linkage with production and work, increase investment in infrastructure and equipment of schools and vocational training centers” (Argentine Education Finance Law of 2005). To this end, the administration of President Cristina Kirchner sought to improve the infrastructure and equipment of vocational and other schools, including a “one laptop per student” program (Conectar Igualdad). This “digital inclusion” initiative provided five million laptops to schools throughout Argentina between 2010 and 2015 and received awards form international organizations like the UNDP.

As of recently, vocational technical education programs were less popular among Argentinian students than programs in general academic streams. In 2015, there were 641,489 students enrolled in vocational programs at 1,615 institutions throughout the country. This compares to a total of 3.95 million students enrolled in secondary education (including vocational programs). Vocational programs are far more popular among male students – 67.7 percent of students enrolled in vocational programs in 2016 were male, compared to 32.3 percent of females.

Admission to Higher Education

All secondary school graduates who hold a Bachiller or Tecnico are legally entitled to enroll at a public university. This was reaffirmed in a 2015 Higher Education Directive which mandated free and unrestricted access to university-level education at public institutions and enacted a prohibition on tuition fees for undergraduate programs at public institutions. The fact that the new directive prohibits university entrance examinations raised concerns among university authorities and critics who contend that the reform violates university autonomy and hinders universities from selecting the right candidates for their programs. Private institutions are still allowed to require entrance examinations for admission.

In the absence of entrance exams, admission criteria at public universities in Argentina vary by institution and program. Some universities require a minimum high school GPA or completion of a preparatory program, especially for programs in high demand. The Universidad de Buenos Aires, for instance, requires all students to complete a one-year preparatory program (Ciclo Básico Común) prior to admission into undergraduate programs. These types of prep-programs have become more common since 2015 as some universities now use prep-programs in lieu of entrance examinations.

At the same time, preparatory programs help promote equal opportunities by equalizing student preparation among students from socially disadvantaged families or under-performing provinces. Universities therefore have established prep-programs also with the aim to ensure that promotion and graduation rates are not dependent on the place of origin or socioeconomic background.

Higher Education Institutions (HEIs)

There are two distinct types of HEIs in Argentina: The first category includes universities and university-level institutions (Educación Universitaria), while the second category includes post-secondary institutions dedicated to technical/vocational education, as well as teacher training schools and arts schools (Educación No-Universitaria/Educación Terciaria). As mentioned before, these two sub-systems are administered by different state agencies and follow different regulations.

Universities

As of 2018, there were 111 universities and 19 university-level institutions (Instituto Universitario) in Argentina. Out of these, 57 universities and 4 university-level institutions were publicly funded. Unlike multi-disciplinary universities, institutions classified as ‘university-level’ institutions are typically mono-disciplinary institutions that offer university programs in specific fields (medicine, arts, aviation etc.) and include training institutions for the army and the police.

In addition, there are 49 private universities and 13 private university-level institutions. Private institutions were not allowed to operate in Argentina until 1958 and their degrees were not officially recognized until the late 1980s unless graduates also sat for a qualifying state examination. Today, private institutions are fully recognized, but are not allowed to operate as for-profit institutions.

Finally, the University of Bologna and the Latin American Social Sciences Institute (FLASCO), which operate in Buenos Aires, are recognized as foreign institutions.

Non-University HEIs (Educación Terciaria)

In 2015, the non-university higher education system included 1,046 public institutions and 1,193 private institutions (2,606 teaching facilities in total when adding different branches or campuses). Commonly referred to as “institutos terciarios” (or instituciones no universitarias), this category is a heterogeneous group that includes various types of institutions, including the Escuela Superior (higher school), Instituto Superior (higher institute), Instituto de Formación Docente (teacher training institute), Colegio (college), Fundación (foundation) and Centros Estudios Superior (center of higher study).

Institutos terciarios generally operate under provincial legislation, even though they are also bound by guidelines set forth by national authorities, such as the National Institute of Technological Education or National Institute of Teacher Training. In comparison to the university system, institutos terciarios have traditionally offered a broader variety of programs with less standardization between provinces. This diversity and lack of articulation creates challenges for the transferability and recognition of credentials between provinces, as well as between institutos terciarios and the university sector – a situation that was particularly problematic prior to recent reforms to increase the standardization of post-secondary education nationwide.

One such reform was the establishment of a ‘National System of Higher Education Recognition’ by the federal Ministry of Education in 2016. The reform aims to facilitate mobility and articulation between university-level institutions and institutos terciarios. It created a national credit system (Reconocimiento de Trayecto Formativo – RTF) that defines one academic year as 60 RTF units akin to the ECTS credit system in Europe. Other reforms included the establishment of a national vocational education database and a federal registry of teacher training institutions and programs. A national qualifications framework that classifies and benchmarks academic qualifications would be beneficial for Argentina, but does not exist as of 2018.

Institutos Terciarios mostly offer shorter programs at the sub-degree level – they are not allowed to award university-level credentials. One area where terciarios feature prominently is teacher education. In 2015, 58 percent of all students in the non-university sector were enrolled in teacher-training colleges (Institutos de Formación Docente) compared to 40 percent in technical or vocational programs.5 Teacher training colleges award 4-year post-secondary teaching degrees that entitle to teach at the elementary and secondary levels (see teacher education section below).

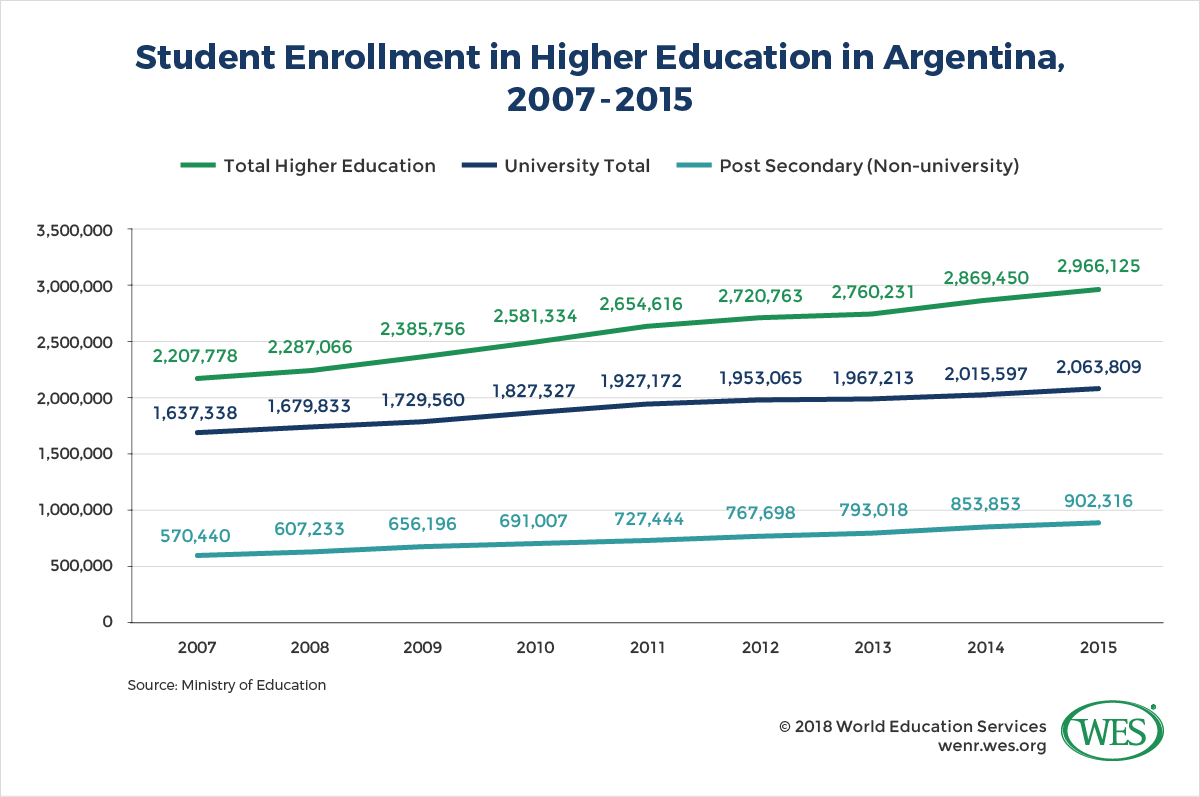

Student Enrollments

Argentina’s student population has grown strongly over the past decades: according to the UIS, the number of students at all levels of tertiary education almost doubled between 1998 and 2015. As per data published by the Argentine Ministry of Education, the number of students enrolled in post-secondary education (university and non-university) increased by 34 percent between 2007 and 2015 alone, from 2.2 million to 2.97 million students.

About two thirds of students in Argentina study at university level institutions. In 2016, there were a total of 2,100,091 students (1,939,419 undergraduate students and 160,672 graduate students) enrolled in Argentina’s university system. Females outnumbered males among these students by a significant margin of 57.6 percent to 42.4 percent. By comparison, 902,316 students were enrolled in institutos no universitarios/terciarios in 2015 (there is no data available for non-university enrollments in 2016).

In the university sector, students are primarily enrolled at public institutions – fully 79 percent of students attended public institutions in 2016. Private HEIs are mostly smaller institutions located in urban centers. While 25 percent of students in Buenos Aires and the Central Region were enrolled in private HEIs, private enrollments in the Southern Region made up only 6 percent of the student population.

Eighty-one percent of private institutions have less than 10,000 students, while the majority of public institutions enroll more than 10,000 students with big national universities like the National University of Córdoba having student enrollments above 100,000. The University of Buenos Aires (UBA), Argentina’s largest HEI, is among the universities with the highest number of students in all of Latin America (it had 328.361 students in 2012).

Private institutions have a larger market share among terciarios. Forty-six percent of students in post-secondary technical vocational programs (excluding teacher training programs) studied at private institutions in 2014 compared to 53.6 percent at public institutions. As in the university system, female students outnumbered male student in this sector by a significant margin of 58.1 percent to 41.9 percent.

University Rankings

Given its advanced economic standing in Latin America, Argentine universities do not fare as well in some international university rankings as one might expect when compared to universities from other Latin American countries like Brazil, Chile, Mexico or Colombia. In the latest 2017 Times Higher Education ranking of Latin American universities, only one Argentine university, the National University of Córdoba, ranked among the top 50 (rank 26-30) while Brazil had 16 institutions in the top 50, including the top-ranked State University of Campinas. Chile also had 16 universities in the top 50, whereas Mexico and Colombia had six and five universities, respectively, represented among the top 50 institutions.

That said, Argentine universities ranked much higher in the latest QS 2018 Latin America rankings, where six Argentine universities featured among the top 50, with UBA ranking 9th out of 50. UBA is also the third-highest ranked Latin American university after Brazil’s University of Sao Paolo and Mexico’s National Autonomous University of Mexico in the latest Shanghai Ranking. The disparity in rankings is perhaps testimony to the sometimes unreliable nature of university rankings as a measure of institutional quality.

Quality Assurance and Accreditation

Faced with a growing number of HEIs and student enrollments, Argentina in 1995 created a dedicated body for quality assurance in university education – the National Commission for University Evaluation and Accreditation (CONEAU) under the auspices of the Ministry of Education. Universities are required to undergo evaluation every six years – a two-step process that involves institutional self-assessments (Autoevaluación Institucional) and an external evaluation by CONEAU (Evaluación Externa). New universities need approval from CONEAU to operate in Argentina.

In addition, CONEAU accredits individual study programs in state-regulated professions. There are presently about 20 state-regulated professions that are considered critical for public safety and range from medical doctors to architects, lawyers, accountants, nurses, chemists, geologists or computer scientists (a list of state-regulated professions is available on CONEAU’s website). Programs are first accredited for an initial 3-year cycle followed by 6-year cycles. Evaluation is based on institutional self-assessment and external evaluation by CONEAU. The commission maintains an online database of accredited undergraduate and graduate programs.

Outside the university system, quality assurance and oversight is provided by a variety of different institutions with the Federal Council of Education being the main coordinating body. The National Institute of Technological Education (Instituto Nacional de Educación Tecnológica – INET), for instance, is responsible for ensuring quality in vocational and technical education, while the National Institute for Teacher Training (Instituto Nacional de Formación Docente –INFD) evaluates and accredits non-university-level teacher training institutions and programs. INFD maintains an online registry of accredited teacher training colleges and programs.

The Higher Education Degree Structure

Pregrado (Sub-degree programs)

Programs in the pregrado category include short-term programs with a vocational focus (carreras cortas) and intermediate programs (títulos intermedio) that take between two and four years of full-time study to complete. Intermediate degrees have a variety of different names, including Técnico Universitario (University Technician), Técnico (Technician), Técnico Superior (Higher Technician) or Bachiller Universitario (University Bachelor). With the exception of those qualifications that carry the designation “universitario”, these credentials may be awarded by both university-level institutions and terciarios. Depending on the program, study completed in sub-degree programs may be transferred into degree programs (grado) at universities.

Given the academic autonomy of universities, the length of programs and credential names of intermediate degrees vary by institution. An intermediate degree in law may last two years at one university, but involve three or four years of study at another institution. Similar programs may lead to the award of a Técnico Universitario at one institution, yet conclude with the award of a Bachiller Universitario at another HEI.

At UBA, a Técnico Universitario takes 2.5 years (1,600 hours of instruction) to complete. Técnico Universitario programs typically have a higher theoretical study component than programs leading to a Técnico or Técnico Superior. Common majors in this category include accounting, commerce, engineering, computer science, journalism or translation.

The Técnico Superior is the most commonly awarded credential in more vocationally oriented and applied programs. It is usually the highest credential awarded by terciarios except for four-year teaching qualifications (see below), but it may also be awarded by universities. Programs currently last either three or four years, although two-year programs also existed until recently. Minimum requirements range from 1,600 to 2,000 hours of instruction, of which at least 20 percent should be dedicated to practical training. It is not unusual for these programs to be studied in part-time mode by working adults. Common areas of specialization include business administration, allied health, computer science, environmental safety and hygiene, agriculture, multimedia and tourism and hospitality management.

Grado (degree programs)

Grado programs typically lead to a Licenciado (Licentiate) or Título Profesional (Professional Title) – credentials that can only be awarded by university-level institutions. By law, all Grado programs include a minimum of 2,600 hours of classroom instruction taken over a period of at least 4 years. Degrees in professional disciplines like medicine, architecture or veterinary medicine may take up to six or seven years to complete. Admission is based on high school graduation or lateral entry based on a títulos intermedio from a university-level institution. Many university-level institutions also offer articulation programs for graduates from terciarios. These programs are known as complementary cycles (ciclos de complementación) and generally require between one and two years of full-time study.

Licenciado programs are typically offered in academic fields like social sciences, sciences, business or liberal arts. The Título Profesional, on the other hand, is more often awarded in state-regulated professions. However, the Licenciado designation may also be used for regulated professions. Given the autonomy of universities, a Grado program in the regulated profession of psychologist, for instance, may conclude with the award of a Título de Licenciado en Psicología or a Título de Psicólogo, depending on the institution. Program lengths for psychology also vary and range from four to four-and-a-half, five or six years.

Programs are highly structured with few electives and may conclude with a thesis or a research project or field work. Curricula are specialized with few general education courses, except for general subjects related to the major taken in the first years of the program.

Posgrado (postgraduate programs)

Especializaciones (specialization programs) are short post-graduate programs intended for further specialization in fields related to the major in which the Grado degree was earned. These programs lead to the award of the Título de Especialista (Title of Specialist) and most commonly last one year, except in the case of medical specialization programs, which can last up to five years. In some cases, specialization credentials may be earned as an intermediate qualification en route to a master’s degree.

Maestrías (Magister) programs are either offered as graduate research programs in academic disciplines (Maestría Académica) or as more professionally oriented programs (Maestría Profesional). Programs lengths vary, but most programs last two years and conclude with a thesis (in the case of academic programs) or a project (in the case of professional programs). Admission usually requires a five-year Grado credential. Sometimes, a Título de Especialista may also be required for admission. The final credential awarded is typically called the Título de Magister or Título de Master.

Doctorado (doctoral) programs are terminal research degrees that last a minimum of two years after the Licenciado, but are often much longer (up to six years). Some programs involve two years of coursework and a dissertation, but other programs are pure research programs that only require completion of a dissertation without additional coursework.

Number of Programs Offered at Different Levels

In the 2016 academic year, Argentine university-level institutions offered at total of 12,617 academic programs, including 2,605 Pregrado programs, 5,798 Grado programs and 4,214 Posgrado programs (1,969 Especialidad programs, 1,494 Maestría programs and 751 Doctorado programs). The most popular fields of study among new enrollees in Pregrado and Grado programs in the university system in 2015 were social sciences (38.9 percent), applied sciences (21.9 percent), human sciences (19.4 percent) and health sciences (15.5 percent). University programs can be searched for in an online database maintained by the Secretaría de Políticas Universitarias.

Teacher Education

Teacher education in Argentina predominantly takes place at teacher training institutes (Institutos de Formación Docente) in the non-university sector, although many universities also offer teacher-training programs. The teacher training institutes are under the authority of the provinces, but training programs are regulated at the national level since the mid-2000s. While teacher education programs could have varying lengths before, laws passed in 2006 and 2008 mandate that all programs now have a minimum length of four years, including 2,600 hours of classroom instruction. Education programs at universities often last five years.

Admission is generally based on the Bachiller and curricula include general education subjects, specialization subjects and pedagogical subjects. An in-service teaching internship is mandatory in the last year of the program. A degree is required to teach at all levels of school in Argentina. Commonly awarded credentials include the Título de Profesor de Educación Primaria (Title of Primary School Teacher) or the Título de Profesor de Enseñanza Secundaria (Title of Secondary School Teacher). Graduates of teacher training programs at terciarios can obtain a university qualification by completing an articulation program at universities (Ciclo de Articulación para Licenciatura en Ciencias de la Educación).

The Struggle of Argentina’s Teachers

In 2017 and 2018, Argentina saw large-scale demonstrations and nationwide teacher strikes over inadequate pay. Teacher salaries in Argentina are low and real wages have been declining in recent years. While there are vast differences in salaries between provinces, the entry-level salary for teachers in all provinces is far beneath the salary levels of bus drivers, for example. Whereas a teacher with ten years of experience earned a monthly salary of 23,349 pesos in the province of Santa Cruz and 9,470 pesos in the province of Santiago del Estero in 2016, the bus driver’s union in the same year negotiated a monthly base salary of 21,000 pesos.

There have been significant nominal wage hikes for teachers in recent years. A number of provinces recently enacted pay raises between 15.5 and 40 percent. However, Argentina’s inflation rate amounted to more than 20 percent in 2017, so that these raises are modest if not insufficient to adjust for monetary depreciation.

Protests over low teacher salaries are also part of a larger controversy over gender inequality in Argentina. School teachers in Argentina are predominantly female. Current data is scarce, but 87.4 percent of elementary school teachers were females in 2008 (UIS). More than 75 percent of students currently enrolled in teacher training schools are women.

Arts Education

Argentina has a long tradition of arts education that was originally shaped by European immigrants from countries like Italy, Spain or Germany. Argentinean composers, musicians and other artists have been recognized for their works by global audiences since the mid-19th century. Several public and private conservatories of music were instituted throughout the 20th century to make Argentina a leading country in performing arts education in Latin America.

Since arts education in conservatories is based more on artistic performance and creativity than theoretical academic study, arts education has historically been treated differently than other education sectors in Argentina. Arts programs were considered “specific arts careers” regulated by the individual provinces. However, the Federal Education Council in 2010 enacted a number of reforms in arts education that incorporated conservatories and other arts schools more closely into the education system. Depending on the level and nature of study, arts schools were grouped into secondary schools, vocational-technical institutions and teacher training schools. Since then, post-secondary arts institutions award the “Técnico Superior” – a vocational-technical qualification on the face of it. In the case of arts schools that train teachers, institutions now award the “Título de Profesor” and follow the same regulations as other teacher training schools. Despite these reforms, however, many provinces and the city of Buenos Aires continue to treat arts institutions differently than vocational-technical institutions.

Professional Education

Professional entry-to-practice degrees in disciplines like medicine, dentistry, veterinary medicine, architecture or law are earned in long single-tier Licenciatura-level programs of five to seven-year duration. Curricula and training guidelines for professional programs are set by the Ministry of Education and all programs must be accredited by CONEAU.

Only university-level institutions that have obtained programmatic accreditation from CONEAU may award Licenciado-level degrees in the professions. Entry is generally based on the high school diploma (i.e. the Bachiller), but admission is competitive and institutions usually have additional requirements, such as completion of preparatory programs or, in the case of private institutions, entrance examinations.

There are currently only 37 universities and four university-level institutions that offer programs leading to a professional degree in medicine (Título de Doctor en Medicina – Title of Medical Doctor). These programs are most commonly six to seven years in length and include a minimum of 5,500 hours of study, including at least 3,900 hours of academic study and clinical training and a medical internship of at least 1,600 hours.

Dentistry programs are offered at 17 universities and 1 university-level institution and lead to the award of the Título de Odontólogo (Title of Dentist). Programs are five to six years in length and include a minimum of 4,200 hours of instruction, divided into academic study and clinical training/internship(s).

Certification in medical and dental specializations involves an additional two to five years of training that conclude with the award of the Título de Especialista (Title of Specialist).

Study programs in veterinary medicine are offered at 18 universities and last most commonly between five and six years, including a minimum of 3,600 hours of study. The final credential awarded is the Título de Médico Veterinario or Título de Veterinario (Title of Doctor of Veterinary Medicine or Title of Veterinarian).

The standard professional degree in law is the Título de Abogado (Title of Lawyer), which is earned upon completion of a four to six-year program after secondary education. Programs include a minimum of 2,600 hours, including at least 260 hours of professional practice. 66 universities and 2 university-level institutions currently offer professional programs in law.

Programs in architecture typically last five to six years (a minimum of 3,500 hours of instruction) and lead to the Título de Arquitecto (Title of Architect). There are 36 universities that offer architecture programs in Argentina.

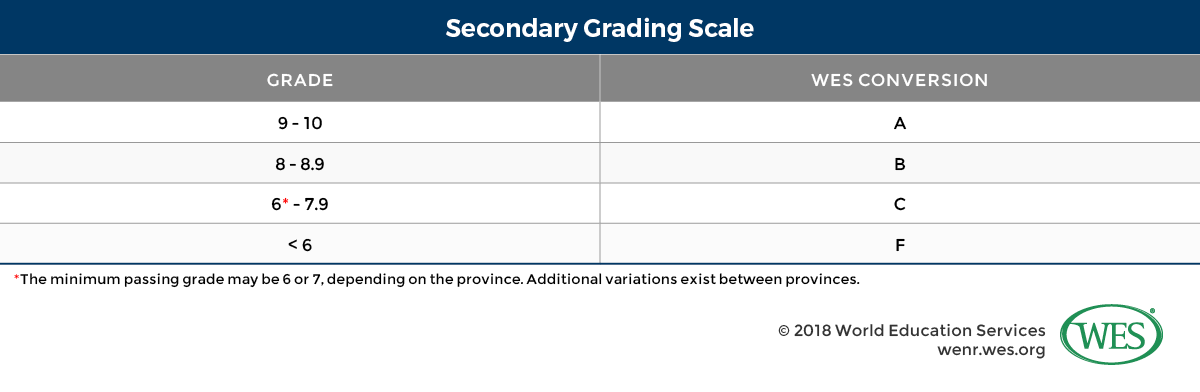

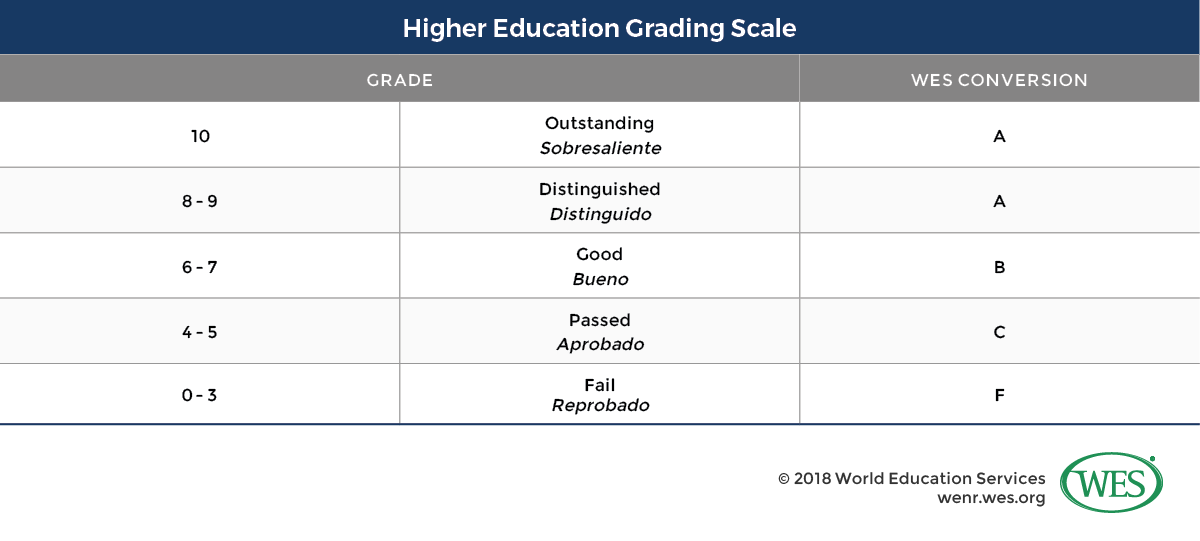

Challenges for Credential Evaluation

The main challenge in assessing Argentine qualifications is the non-standardized nature of credentials, especially in light of the numerous changes and reforms over the last three decades. While the education system is becoming increasingly standardized, the assessment of older credentials sometimes requires case-by-case evaluation of individual programs, especially in the case of non-university qualifications. In previous decades, there were big differences between provinces in terms of program length, grading scales and graduation criteria. Older sub-degree qualifications and certificates were issued in the absence of agreed standard national criteria and there is still a certain overlap between universities and institutos no universitarios/terciarios, both of which offer similar programs at the intermediate level. This diversity and non-conformity sometimes complicates the evaluation of Argentine credentials.

WES Documentation Requirements

Secondary Education

- Photocopy of graduation certificate/diploma – submitted by the applicant

- Academic transcript (Certificado Analítico de Estudios/ Calificaciones) – sent directly by the institution attended

- Precise, word-for-word translations of all documents not issued in English

Higher Education

- Photocopy of degree certificate – submitted by the applicant.

- Academic transcript (Certificado Analítico de Estudios/ Calificaciones) – sent directly by the institution attended.

- For completed doctoral degrees – a written statement confirming the award of the degree sent directly by the institution

- Precise, word-for-word translations of all documents not issued in English

Sample Documents

Click here for a PDF file of the academic documents referred to below.

- Bachiller (6+6 – Province of Córdoba)

- Bachiller (5+7 – City of Buenos Aires)

- Título de Profesor de Educación Primaria (no universitaria)

- Título de Licenciada en Psicología

- Título de Mėdico

- Título de Magister

- Doctora

1. These numbers reflect improvements since 2009 when 42.94 percent of grade ten students were above the official school age and dropout rates for grade nine, ten and eleven were 11.5, 17 and 10.9 percent, respectively.

2. Argentina ranked higher in the 2015 PISA study, but these results are not representative, since only students from Buenos Aires participated in the test, while students from lower performing provinces were excluded.

3. Student mobility data from different sources such as UNESCO, the Institute of International Education, and the governments of various countries may be inconsistent, in some cases showing substantially different numbers of international students, whether inbound, or outbound, from or in particular countries. This is due to a number of factors, including: data capture methodology, data integrity, definitions of ‘international student,’ and/or types of mobility captured (credit, degree, etc.).

4. Educación Física, Artes, Agro y Ambiente, Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades, Ciencias Naturales, Economía y Administración, Turismo, Informática, Lenguas y Comunicación

5. 523,169 students were enrolled in teacher training colleges, 360,771 students in vocational/technical programs. The remaining 18,376 students were enrolled at institutions that offered both types of programs and other institutions like conservatories of music.