Stefan Trines, Research Editor, WENR

In case you missed it, China is now the “largest trading partner, foreign job creator, and source of foreign direct investment [2]” in Africa. China routinely bankrolls mega construction projects, such as the new headquarters of the African Union and rail system in Addis Ababa, hydro power plants and oil refineries in Angola and Nigeria, or Zimbabwe’s international airport and new parliament building [3]. It recently also established its first overseas military base in Djibouti and has become a major supplier of arms in sub-Saharan Africa.

Some consider China’s “railway diplomacy” a boon for the continent [4], since Chinese funding helps close critical infrastructure gaps and creates economic stimuli [5]. Beijing, for one, promises African countries a “new strategic partnership” that—unlike the exploitation by former colonial powers—would be based on political equality, mutual trust, and win-win economic cooperation [6].

Critics, though, view China’s economic influence as a new form of colonialism that, just like the old system, is premised on the exchange of African raw materials for Chinese goods, while simultaneously shoring up autocratic rulers. In this view, Africa’s growing indebtedness to China will undermine the sovereignty of African countries and curtail their economic development. As Nigerian writer Chika Ezeanya-Esiobu put it [8], the effect of Africa’s reliance on external assistance “will be the continued political and economic manipulation and domination of the region by the West, and now China, and soon the rest of the non-African world.”

Indeed, China’s economic activities have sparked a “new scramble for Africa [9].” National Security Advisor John Bolton announced in 2018 that the U.S. “would lavish money and greater attention on the African continent, casting it as a crucial battleground in the global economic contest between the United States and China [10].”

India, likewise, has made Africa a top foreign policy priority [11]. According to former Indian Foreign Secretary Lalit Mansingh, an “important factor for the current government is clearly China, that it has marched ahead in a continent we thought was ours by tradition. I think it came as a shock for India [12].” Highlighting the heightened interest in the last frontier of the global economy, the Economist reported that from “2010 to 2016 more than 320 embassies were opened in Africa, probably the biggest embassy-building boom anywhere, ever [9].”

One area where foreign governments are competing for influence in Africa is education. China, for instance, is increasingly supplementing its loan diplomacy with “cultural exchanges, sending … teachers to work abroad, welcoming students from other nations to study in China, and paying for Chinese-language programs abroad [13].” Whether it’s pursued for noble motives or out of political self-interest, the advancement of educational causes helps to win over hearts and minds—a form of persuasion that political scientists commonly call “soft power [14].”

This article reviews the different forms of Chinese and Indian involvement and assistance in African education in recent years. Both countries are rapidly expanding their aid efforts in education and will undoubtedly leave a growing mark on the education systems of African countries. We will describe China’s diplomacy through cultural institutes, the country’s rise as a study destination for African students, and its aid efforts in educational capacity building. Afterwards, we’ll portray India’s interests and initiatives in Africa before concluding with some brief reflections on the benefits of increased “South-South” cooperation with the continent.

China’s Attempt to Reach Hearts and Minds With Confucius Institutes

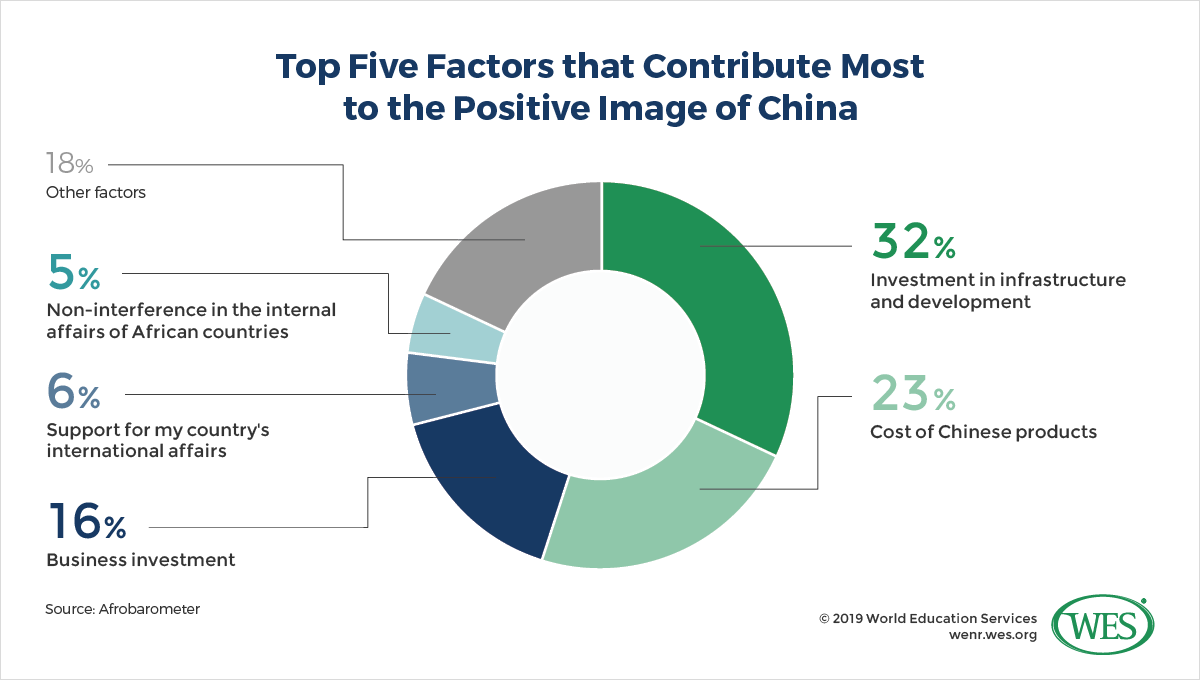

Compared with the former colonial powers Great Britain and France, or English-speaking countries like the U.S. or India, China has the disadvantage of having languages that are not commonly understood or spoken in Africa. Nor is Chinese culture as well-known as that of the U.S., which is ubiquitously telecast to every corner of the globe in Hollywood movies. However, China’s growing role in Africa has apparently been met with positive views [15] in a majority of African countries. According to opinion surveys [16] conducted in 2014 and 2015 by the research project Afrobarometer, 63 percent of respondents in 36 African nations stated that China had at least a somewhat, if not a strong, positive influence on their countries, and that China’s economic model represented the most viable pathway to economic development after that of the United States.

To even further strengthen its image and to advance the internationalization of the Chinese language, Beijing has over the past decade vastly expanded its network of Confucius Institutes (CIs) in Africa. According to Hanban, the organization that runs the CIs, their number increased from only one in Kenya in 2005 to at least 53 on the continent in 2019 [18].1 [19] CIs are usually housed at and affiliated with universities in the host nations, such as the University of Nairobi or the University of Cairo, while being largely controlled by the Chinese government [20]. They are designed to foster Chinese language learning and promote the understanding of Chinese culture. Beijing has opened more than 500 of these institutes worldwide and views them as a helpful tool in its global communications strategy, which President Xi Jinping has described as follows: “We will improve our capacity for engaging in international communication so as to tell China’s stories well, present a true, multi-dimensional and panoramic view of China, and enhance our country’s cultural soft power [21].”

A key difference between CIs on the African continent and those in other regions like North America, Europe, or Asia is that CIs in underresourced African countries are not simply an addendum to existing East Asian studies departments. Rather, they are usually the only tertiary institutions teaching Chinese studies and languages [22]—a fact that gives them an outsize influence on shaping perceptions of China. In this sense, CIs make an academic contribution to the study of Chinese affairs in Africa, but they are often accused of offering a lopsided, ideologically tinted view of China and of issues like the political status of Taiwan or Tibet. Sweden’s Institute for Security and Development Policy has described CIs as “an image management project, the purpose of which is to promote the greatness of Chinese culture while at the same time counterattacking public opinion that maintains the presence of a ‘China threat’ in the international community [23].”

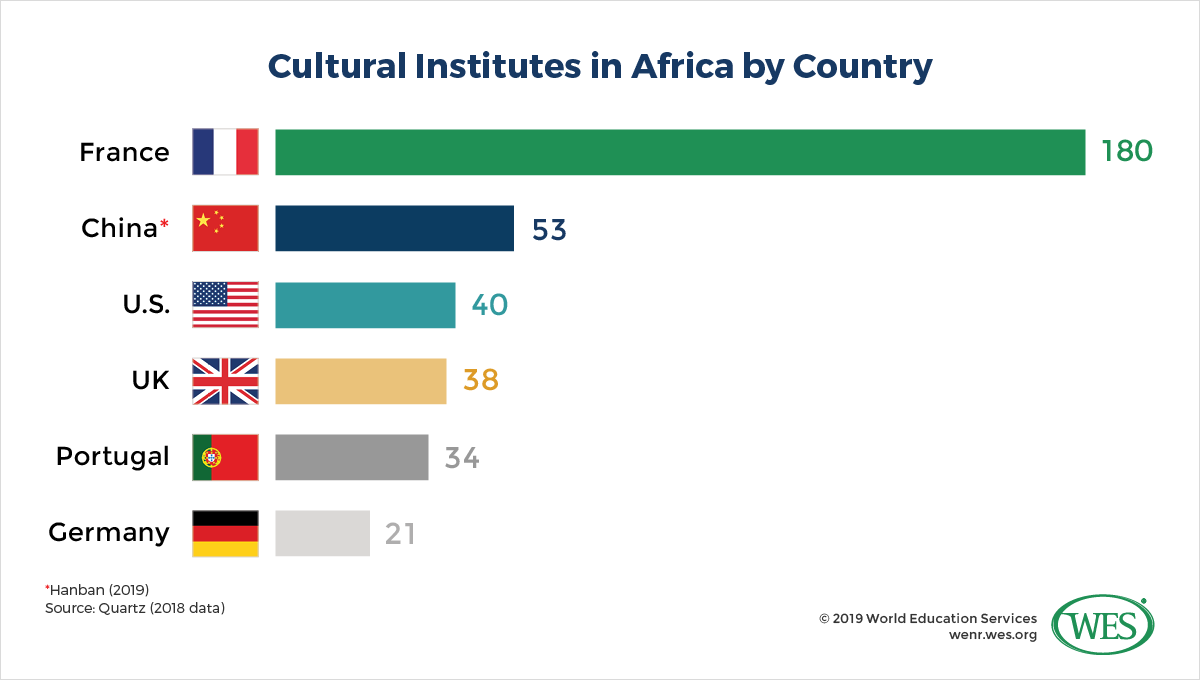

The use of cultural institutes to advance influence in foreign countries and promote an idealized version of national culture is not unique to China, nor new. France’s Alliance Française [24] operated overseas cultural centers as early as the late 19th century. What is remarkable, however, is the speed with which the Chinese institutions have appeared on the international scene in recent years. Today, France remains the only country that still has more cultural centers in Africa than China. According to Hanban, CIs have been opened in 34 African countries in addition to 25 smaller “Confucius classrooms” housed in elementary and secondary schools throughout the continent.

The size of some of the CIs is considerable as well. The institute at Cameroon’s University of Yaoundé, for instance, has ties with eight local universities and several private language schools and enrolled 10,000 Cameroonian students in 2017 [25]. Notably, the programs offered through CIs are not necessarily confined to short-term courses. For instance, Uganda’s Makerere University has announced that beginning in 2019 it will offer a Bachelor of Chinese and Asian Studies program in collaboration with Hanban [26]. Classrooms and facilities for the program will be paid for by Bejing, and top students will be invited for study visits in China [27]. Uganda’s plans to make Mandarin a compulsory subject [28] of its high school curriculum reflects the rise of Chinese as a language of global importance—as does the recent decision of Kenya [29] and South Africa [30] to introduce Mandarin as an elective language in public elementary and secondary school. It is likely that Mandarin Chinese will become a much more widely spoken language on the African continent in the years ahead.

Promotion of International Student Mobility

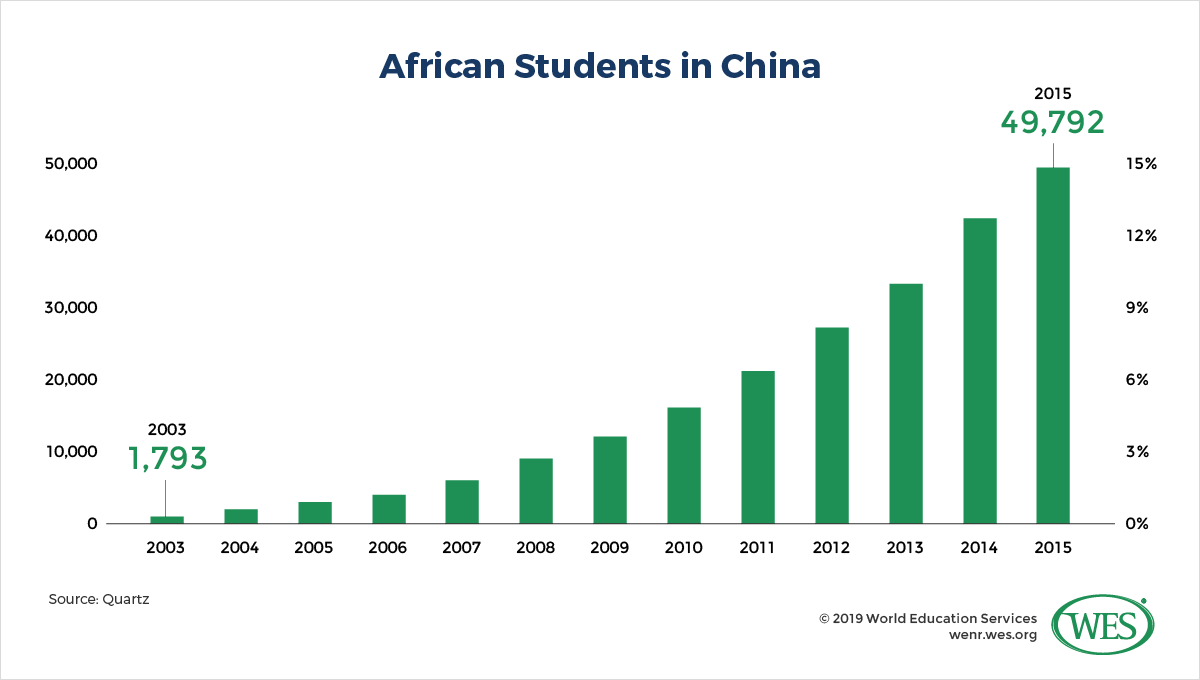

Beyond cultural diplomacy through its institutes, China seeks to strengthen ties to future African elites by acculturating young Africans as international students in China itself, similar to the way the U.S. has for decades used Fulbright scholarships to advance its soft power. Much has been written about international student mobility to China in this publication [32] and elsewhere. Suffice it to say that China has become an increasingly important study destination, notably for students from developing countries. According to government data released by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) [33], one of the few available data sources for international students in China, the number of African students studying in China rose by a whopping 3,335 percent [32] between 2003 and 2016, from 1,793 to 61,594 students—the fastest growth rate among all world regions.

While these numbers include various forms of short-term study visits and are hard to compare with data from sources like UNESCO, they reflect an enormous inflow of African students, fueled by Chinese scholarship funding, affordable study options in China, and other incentives. Kenya is a case in point: Chinese media reported in 2017 [34] that 1,400 Kenyans were studying in China after Beijing had doubled its scholarship quota in 2011 and provided 1,000 scholarships to Kenyans. Just one year later, Kenya’s ambassador to China announced that the number of Kenyan students in the country had since surged to 2,400 [35]. Other countries boasted even larger gains: There were 2,829 Ethiopian students in China in 2016 compared with only 933 in 2012, while the number of students from Ghana, the top African sending country, tripled from 1,753 in 2011 to 5,552 in 2016 [36]. Given the scarcity of funds for an expensive overseas education among African youths, scholarships are likely a significant pull factor, but it should be noted that 87 percent of all 492,000 international students in China in 2016 were self-funded [37], according to the Chinese Ministry of Education.

Aid to Strengthen Domestic Capacities and Skills

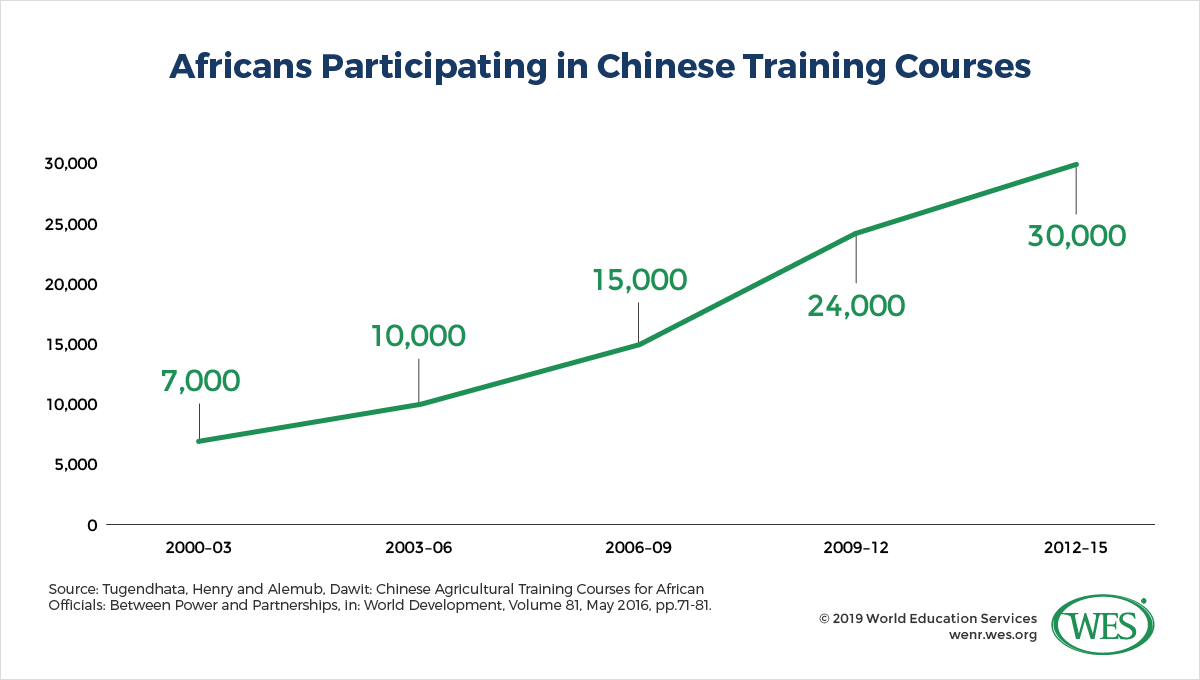

What is notable about China’s academic cooperation in Africa is that many of its scholarship programs are devoted to skills training and socioeconomic development. Every year some 10,000 African civil servants [39] receive vocational training in China at universities, government agencies, and companies in areas like agriculture, health care, or poverty reduction. Most of these training courses are short-term programs that last just a few days or weeks, but their number has skyrocketed and now far outstrips the number of similar training programs provided by other countries. Between 2012 and 2015, some 30,000 Africans received scholarships, and Beijing intends to expand these numbers even further. At the latest 2018 Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), a large summit meeting between China and 53 African states, Beijing announced that it would not only further expand its CIs across the continent, but it would “provide Africa with 50,000 government scholarships and 50,000 training opportunities for seminars and workshops and train more professionals … and build platforms for … exchanges and cooperation [40].”

But Chinese development aid in education comes in various shapes and forms. To name just a few examples, China supports the construction of hundreds of rural elementary and secondary schools [42], and provides learning materials and equipment to African universities. It is planning the creation of five transportation universities [43] across Africa, and currently supports digital literacy projects [44] in countries like Kenya. The Chinese government also funds more than 20 rural agricultural training centers in Africa to modernize farming. More than 1,000 students have been trained at Chinese agricultural centers in Rwanda alone [45]. In 2012, Bejing donated USD$8 million [46] to UNESCO to strengthen teacher training in Africa. In Malawi, China helped finance [47] the country’s first dedicated science university—the Malawi University of Science and Technology.

Contrary to the perception that Chinese aid is mostly a tool to advance influence and access to markets, there are also small but growing numbers of Chinese nationals volunteering as teachers in underserved African schools, and Chinese NGOs building schools in slums, or providing tuition assistance and housing for teacher trainees [48]. However, much of China’s assistance remains interwoven with business projects. For example, “more than 45,000 local staff [34] received professional skills training” during the construction of the Mombasa-Nairobi railway, Kenya’s largest infrastructure project since independence. Chinese firms like industry giant Huawei are setting up information technology classes at Kenyan universities [48] to upskill the local workforce. This kind of involvement helps to transfer knowledge to African societies but also serves Chinese business interests. These interests are on display in recent initiatives like the establishment of a joint academic institute in Morocco specifically devoted to studying China’s Belt and Road initiative [49].

India in Africa

In some ways, India’s involvement in education in Africa follows a different approach and is based on a different legacy. The Indian government does not systematically promote Indian culture the way China does with its vast network of Confucius Institutes. Compared with China’s, India’s relationship with African nations also has a longstanding tradition—it has been shaped by centuries of sea trading [50] between India and Africa’s eastern seaboard. The presence of more than 2.2 million ethnic Indians in South Africa and East African countries like Kenya and Tanzania has also helped strengthen relations, as did the common use of English, a common outlook on decolonization, and political cooperation in the Non-Aligned Movement [51]. India was a principal architect of the movement and one of its leading proponents under Jawaharlal Nehru, the country’s first Indian prime minister.

India’s current objectives in Africa are similar [52] to China’s, however. The country has a keen and growing interest in Africa as a market for its products and a source of commodities for its fast-expanding economy. Beyond that, efforts to deepen ties with Africa are an attempt to balance China [53]’s influence and shore up diplomatic support on the global stage for objectives like a permanent seat for India on the UN Security Council [54]. Delhi views China’s rapid economic and political expansion, notably the Belt and Road Initiative, as a geopolitical challenge that it seeks to counter, including in Africa [55].

The challenge for India in this competition is that it cannot match China’s financial resources nor China’s voluminous trade with Africa. India’s infrastructure projects pale in comparison to China’s. Notably, India’s soft power in Africa also rests more on people-to-people and private business contacts than government stewardship. Until recently, India’s approach to Africa was arguably less strategic and forceful than China’s.

However, the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi has pursued Indian interests in Africa with remarkable intensity. Modi has toured Africa twice, in 2016 [56] and 2018, with the latter visit including the first-ever official Indian state visit of Rwanda [53]. Likewise, plans to open 18 Indian embassies on the continent by 2021 [57] were announced last year. Importantly, relationships have been strengthened in a series of massive India-Africa Forum Summits, the third of which saw more than 1,000 delegates from all 54 African countries visit New Delhi in 2015 and represented the largest Indian diplomatic outreach [58] to Africa in recent history.

Economic ties have grown intensely in the wake of this heightened outreach. Policy initiatives like duty- and quota-free access to India’s market for least developed countries, as well as infrastructure development aid for African states, have helped to greatly expand bilateral trade, particularly with Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Mozambique, Mauritius, Nigeria, South Africa, and Tanzania. As the African and Indian import-export banks noted in a recent publication, trade “between Africa and India has increased more than eight-fold from US$7.2 billion in 2001 to US$59.9 billion in 2017, making India Africa’s fourth-largest national trading partner, accounting for more than 6.4 percent of total African trade in 2017, up from 2.7 percent in 2001 [59].” By comparison, “China’s trade with Africa hit $210 billion in 2013, with 2,500 Chinese companies operating in the continent [60].”

India’s Education Cooperation With African Countries

Like China, India styles its development aid in Africa as mutually beneficial South-South cooperation and has made various positive contributions to Africa’s development, including through aid in education and human resource development. In what is perhaps the most high-profile example of Indo-African cooperation in education, India in the mid-2000s initiated the Pan African e-Network (PAeN) for tele-education and tele-medicine, a costly endeavor that is considered one of the most ambitious cooperative information technology projects in Africa to date. PAeN links Indian universities like the Amity Institute of Higher Education, the Indira Gandhi National Open University, the University of Delhi, and others with dozens of learning centers in various African countries via a satellite hub station in Senegal in order to deliver distance education programs [61] to thousands of African students. In addition, PAeN connects African medical facilities with medical specialty hospitals in India, enabling Indian doctors to review digitized medical records in Africa and provide live tele-consultations.

Information technology and technical training programs are a primary focus of other Indian projects as well. As noted in a recent report [62] by the Duke Center for International Development, “thousands of people in almost every [sub-Saharan nation] … have received technical training” from India. “The third India-Africa Forum Summit in 2015 allocated $1 billion between 2015-20 for training and capacity development of 25,000 people in Africa in the fields of Agriculture; Food Processing, Packaging and Quality Control; Energy, Infrastructure and Sustainable Development … ICT and e-Governance; Power and Hydrocarbons,” and various other fields.

India-funded initiatives in these areas include the establishment of vocational training centers and institutions for entrepreneurship education in at least 13 African countries, technology parks in Mozambique and Cote d’Ivoire [63], and the India-Africa Institute of Foreign Trade in Uganda [62]. Most recently, Delhi pledged to create a pan-African India-Africa Institute of Agriculture and Rural Development in Malawi. The salaries of Indian faculty and tuition fees for African students will be provided by India for three years [64].

Promoting International Student Mobility

Like China, India also invites African youths to obtain vocational training in India and seeks to boost international student mobility from Africa to its universities. The Indian government offers several scholarship programs for African trainees and researchers, which include its Technical and Economic Cooperation Program (ITEC [65]) and the Special Commonwealth Assistance for Africa Program (SCAAP). According to the Brookings Institution, allocations to these programs have recently surged “from $2.56 million in 2009-10 to $5.43 million in 2015-16” (SCAAP), while “support to African countries through ITEC training slots was also increased from 1,704 in 2008-09 to nearly 4,000 in 2014-15.” In addition, “the Indian Council for Cultural Research … offers nearly 3,365 scholarships annually under 24 scholarship schemes, of which 900 are for African countries [66].”

These scholarships have helped bring a substantial number of African students to India. While small by international comparison, the number of international students in the country has quadrupled over the past decade with students from sub-Saharan Africa making up 19 percent [67] of the total international student body in 2014. Sudan is currently the third-largest sending country of international students to India with more than 2,220 students in 2017/18 [68]. It has been estimated that at least 30,000 Sudanese nationals hold academic credentials from Indian institutions. As India’s former External Affairs Minister Salman Khurshid put it, “We open our educational institutions to our friends from Sudan—about 225 of them go to study in India annually on government of India scholarships, for both long- and short-terms; another 1,500 or more go on a self-financing basis every year [69].” Also notable, the largest number of international students enrolled in Indian doctoral programs come from Ethiopia [68].

There is huge potential for further increases in student inflows from Africa in the years ahead. Population growth and increased demand for education will push growing numbers of African students abroad. India offers them a better education than they could access at home—in English and at lower costs than in Western destinations or China. Many African students also view India as a coveted destination [70]for education in computer science and information technology. Indian universities, in turn, vigorously seek to recruit [71] more African students, notably in East Africa [72].

Indian Universities in Africa

In addition to recruiting Africans for study programs in India, several Indian universities have branched out to Africa to offer education directly on the continent, if often through distance education mode. Indira Gandhi National Open University (IGNOU), the world’s largest university, now offers its distance education programs through study centers in Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Liberia, Madagascar [73] and Namibia. IGNOU’s model of open distance education for the masses has inspired Malawi to create its own Open and Digital Learning University [74]. Amity Institute of Higher Education has established a branch campus [75] in Mauritius, while the prestigious Indian Institute of Technology Delhi is offering master’s programs in collaboration with Addis Ababa University [76]. A number of lesser-known Indian universities have set up shop in countries like Ghana, where India’s growing role in education recently made headlines when the University of Ghana removed a statue [77] of Mahatma Gandhi over charges that Gandhi was a racist—a move that reportedly caused Indian authorities to cancel scholarships for 2,000 Ghanaians [78]. The attempt to erect a statue of Gandhi in Malawi was met with similar resistance from activists [79].

Concluding Thoughts: Is Asian Soft Power Good for Africa?

These objections to statues honoring a foreign iconic figure raise questions about how beneficial the influence of China and India actually is for African societies. Modern education in Africa has always been shaped by external forces, if not directly imposed by them. Even after decolonization, African youths continued to learn in systems that followed foreign Euro-American paradigms—a trend that Western-dominated globalization helped perpetuate. The languages of instruction in most African countries, for instance, remain mostly those of global commerce and former colonial powers (English and French), whereas African languages, of which there are more than 2,000, are generally considered an impediment to economic progress [80]. Instead of developing their own learning models, African nations remain dependent on the outside world to provide better education to their youths. Will curricula developed in India or vocational training programs suited for the needs of Chinese companies make any difference?

Newly built classrooms and academic institutions are a tangible benefit on a continent where some 60 percent [81] of young people between the ages of 15 and 17 are not participating in any form of education (in the sub-Saharan region), and Africa’s total youth population is expected to double to 830 million [82] by 2050. The emergence of greater South-South cooperation in education is generally a positive trend, and some have argued that assistance provided by countries that have more direct experience with developmental challenges could be a blessing. In the end, having more donors means more options for African countries, and it’s encouraging that the assistance provided by China and India is now increasingly focused on education, rather than just transportation or telecommunications technology.

However, the question is whether this assistance can help African nations strengthen their own capacities to develop sustainable, self-reliant education systems. Using a well-known catchphrase, Xi Jinping stated in 2015 that “China supports the resolution of African issues by Africans in the African way [83].” Leaving aside the Confucius Institutes, China does not paternalistically impose its own education model on Africa. But Beijing’s utilitarian hands-off approach, void of Western-style political conditionality, is equally problematic. Many critics consider its policies “tantamount to an export subsidy to Chinese firms, with a side order of backhanders for local elites [84].” If African rulers use the “financing as a patch for poor governance and irresponsible fiscal policies, then China’s no-strings-attached approach to doing business could indeed be disastrous [4].”

Africa doesn’t need classrooms built in the home village of local leaders to curry political favors. The self-serving training of mid-level skilled workers for Indian agri-businesses or the operation of Chinese railroads may have positive spill-over effects for the local populace, but that is not enough to alleviate Africa’s enormous need for education. What the continent requires is assistance to build up more independent Afrocentric education systems, and excellent local universities that can produce their own, local human capital. But South-South cooperation in African education is still in its infancy and generally heading into a positive direction. Time will tell if the increased competition for influence and good will in Africa can make a crucial difference in easing the continent’s learning crisis.

1. [85] Hanban lists a total of 59 CIs, but six of them appear to be still under development.