Confucius Institutes and U.S. Exchange Programs: Public Diplomacy Through Education

Ingrid Hall, Master’s candidate in International Education from George Washington University

China’s Confucius Institutes have come under increased scrutiny over the past few months, spearheaded in part by lawmakers such as Florida Senator Marco Rubio and South Carolina Representative Joe Wilson. Both legislators cite concerns over the Chinese government’s influence over curriculum – mainly its control over re-framing Chinese history and current policy – within U.S. university campuses.

Since their launch in 2004, Confucius Institutes are a platform for enhancing intercultural understanding between China and host countries around the globe. The Institutes are set up as partnerships with China’s Hanban, a part of China’s Ministry of Education overseeing the teaching of the Chinese language. Hanban provides a cash appropriation, pays for visiting faculty, and provides materials for the courses. This infusion of cash and resources is often welcomed by schools that have had to slash budgets for cultural programs.

The Chinese Government’s leverage over curriculum in the Institutes has raised alarms before – notably in 2014 when the American Association of University Professors argued that North American colleges and universities should either dissolve or renegotiate their partnerships. However, some current university administrations feel that these concerns are unwarranted.

While we consider the important questions that are raised by the presence of Confucius Institutes on U.S. campuses – especially in the context of current White House “America First” rhetoric, policies, and personnel – it’s an opportune time to consider how Public Diplomacy through education has been used in the past.

Public Diplomacy through Education

Providing chances for cultural exchange as an exercise in soft power is not new for either China or the U.S. As a tool of the government, this exchange of cultures, languages, and ideas is referred to as Public Diplomacy. Despite similar reasoning and methods (language and student exchange), the U.S. and China both have fundamentally different relationships with their respective governments when it comes to public diplomacy, and their methods are colored by their own cultures and histories. U.S. exchange programs have their roots in World War II, and were heavily shaped by the Cold War era, while China’s Confucius Institutes started this century and dovetail into existing institutions. For context we will explore the history of the U.S. using education as a method of creating goodwill in foreign countries, and then explore the current model being employed by Confucius Institutes.

U.S. Education-Based Public Diplomacy: A Classic Supplement

U.S. Public Diplomacy has undergone several evolutions within recent history. Economic interest initially prompted the US to invest in public diplomacy as a means of ideological influence when it first created the Office of War Information (OWI) in 1942. In the executive order establishing the OWI, President Franklin D. Roosevelt spelled out that the Director of the OWI shall “…Formulate and carry out, through the use of press, radio, motion picture, and other facilities, information programs designed to facilitate the development of an informed and intelligent understanding, at home and abroad, of the status and progress of the war effort and of the war policies, activities, and aims of the Government” (Exec. Order No. 9182, 3 C.F.R., Sec. 4(a)). This executive order put much of the media and means of information in the hands of the U.S. federal government, much to the enthusiasm of Hollywood and advertisers alike.1 The OWI was dissolved after the war, and Eisenhower established the U.S. Information Agency (USIA) in 1953, which used the global information distribution framework created by the OWI to help promote mythical images of American splendor to a wider world caught in the midst of the ideological conflict of the Cold War.2

Selling this idealized version of American culture became paramount in the Cold War. The USIA and its outposts, the US Information Centers (USIS), were cast in a supporting role as the extension of U.S. diplomatic stations.3 Its mission during the time was to “…Promote the national interest and national security of the United States through understanding, informing and influencing foreign publics and broadening dialogue between American citizens and institutions and their counterparts abroad. Although being the arbiters of ideological influence, the disparate needs of USIA’s programs were housed separately from the core agencies that conducted foreign policy.4 Even at the end of the Cold War, embassies in larger countries had a USIS outfitted with information resource centers, cultural centers and libraries, cultural exchange events, Voice of America (VOA) broadcast stations, programs, and counsel for local students seeking to study in the U.S.5

When the time had come for the reconstruction of post-Soviet Europe, the U.S. invested more in aid projects (particularly through USAID) and began to make public diplomatic services contingent upon recipient countries accepting financial aid from the U.S. (accepting the funds is followed by accepting the political principles of the donor country). The USIA slowly became defunct, and they were absorbed into the U.S. Department of State along with the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs (BECA).6

The USIA engaged in Public Diplomacy through three different types of language exchange programs:

- Binational Centers were institutions located in foreign countries dedicated to the promotion of cultural understanding between the host nation and the U.S., but financially and administratively independent from the local USIA/USIS. Some of these centers are still active but are very few in number, and their duties have largely been taken over by the Fulbright Commissions.7

- Direct English Teaching Programs were sponsored by the U.S. government but coordinated and administered by USIA outposts, and these courses were sometimes coordinated independently by a particular outpost.8

- Affiliated Programs were generally conducted outside of USIA jurisdiction, but received resources from the local USIA outpost. Usually, these were programs in universities, private institutions or local government institutions.9

Today these programs are managed under BECA, as well as the Fulbright English Teaching Assistant program, the Humphrey Fellowship Program, the Peace Corps, English Language Specialist Program, and English Language Fellow Program.10 All of these programs are sponsored by English For All, and coordinated under BECA, alongside several other programs for J-1 Visa recipients, teachers of American English, study abroad in the U.S. or EducationUSA. These programs are targeted towards engaging the youth, leaders, and professionals of strategically important countries where the US has long-term political interests (i.e. the Middle East).12

Most of these programs are exchanges for education or professional development, with the option to participate in homestays, or take in some sight-seeing as part of the trip. But the main focus is educating the participants in U.S. methods and systems of leadership, education and organization. While BECA may sponsor these programs, information about application procedures are delegated to the public affairs sections at US embassies or other outposts (i.e. Fulbright Commissions).13

Confucius Institutes: China’s New Education-Based Public Diplomacy

State-sponsored public diplomacy and cultural exchanges take another form altogether in the People’s Republic of China. The Confucius Institutes (CIs) and to a lesser degree the Confucius Classrooms (a version of the CIs for elementary, middle, and high schools) are China’s latest tools in its foray into soft power through education. They are managed by the Office of Chinese Language Council International – otherwise known as the Hanban. The Hanban, serving directly under the Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China, oversees several aspects of China’s public diplomacy, including the Division of Cultural Affairs, the Division of International Exchanges, and a separate division for each world region where Confucius Institutes have been established.14

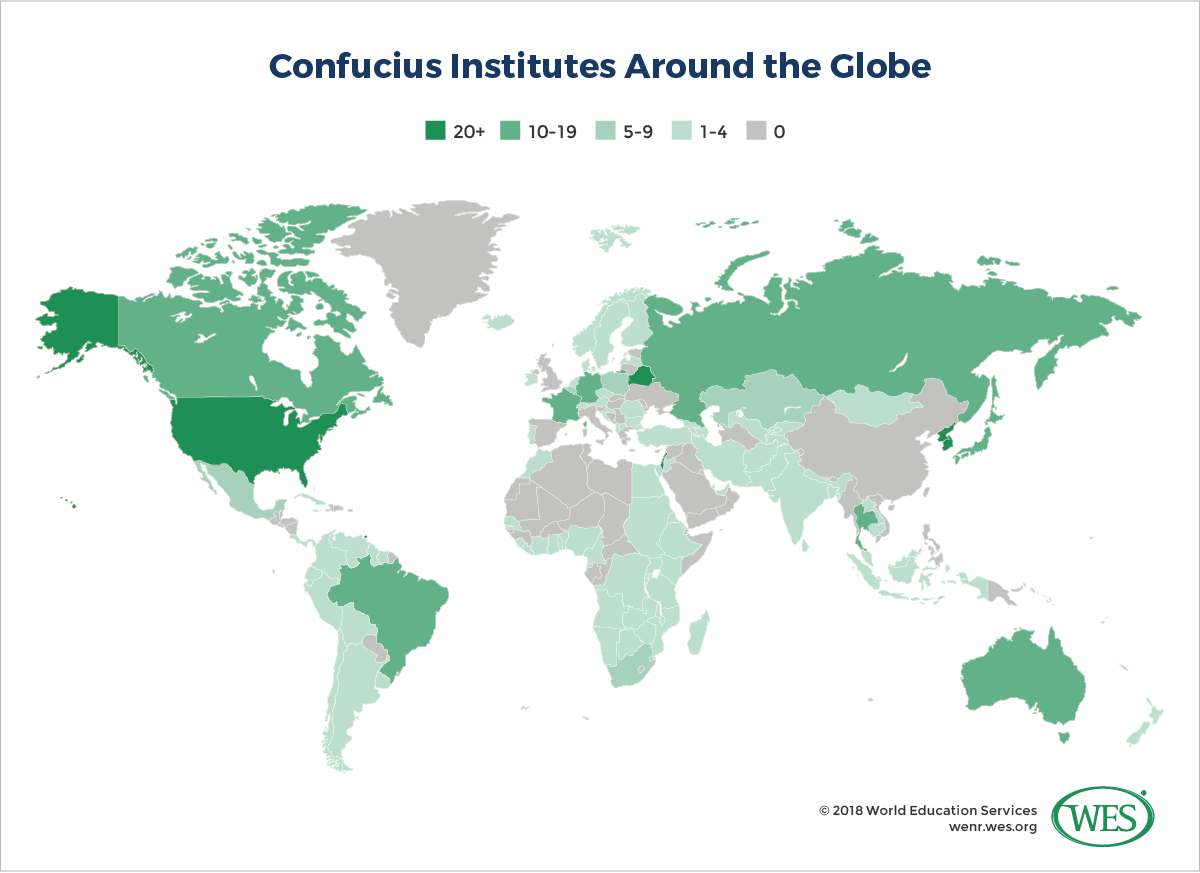

The Hanban and the CIs have the duty of promoting Chinese language and culture in order to facilitate diplomatic exchange and good faith in China. These programs, begun in 2004, have now spread across the word, and the official Hanban website currently lists 110 of these institutes and 501 classrooms in the U.S. alone.15

The Hanban is charged with the maintenance of CIs, including setting establishment criteria, approval of institute’s applications, budgeting, teacher evaluation, the hiring of each CI’s Chinese director, and the organization of the annual CI conference.16 “The process to establish a CI requires universities to review the “Constitution and By-Laws of the Confucius Institutes,” as well as the “Regulations for Administering Chinese Funds” (as an operation funded by the Ministry of Education, all funding for the program is disbursed by the Chinese government). The applicant institution must then prove that there is sufficient demand for the services that the CI provides and that the campus can house and maintain the local CI. The application materials must include detailed information on the proposed CI, including its site location, floor plan, list of resources, funding sources, the proposed managerial structure and operational plans, and a projection of demand for the CI. All documents must have a Chinese duplicate.

The high level of government involvement in the management of CIs is fundamentally different from that of U.S. programs. According to a 2017 report on Confucius Institutes in the United States by the National Association of Scholars, political oversight varies from CI to CI and campus to campus, but the Hanban always maintains control over teaching materials, hiring practices, and the placement of directors for each institute (each CI has a local “foreign” director, and a Chinese director appointed and sponsored by the Hanban).18 Teachers, hired and brought over from China, are screened and evaluated by Hanban and the Ministry of Education before being placed. The Hanban provides a starting grant somewhere in the neighborhood of $100,000 to $150,000 USD and covers all expenses for teaching materials and teachers’ salaries. Each CI has a board of trustees comprised of the foreign director, the Chinese director, and members from each of the host institutions (usually presidents or provosts), and may report to an office on the local campus. The course content offered at 12 CIs recently examined by the National Association of Scholars varied greatly, but was generally comparable to China-specific subjects that could easily be taken at a local university’s language or International Studies department, such as Chinese language, literature, dance, and film.19

By maintaining such rigid control over who is hired and what teaching materials are being used, the Hanban ensures that teachers spread the officially approved narrative of China and maintain China-friendly positions (support for the One-China Policy, denial of the 1989 Tiananmen Square Massacre, explaining away human rights abuses, etc.). For those who are enticed, however, the CIs provide not only opportunities for learning and practicing Mandarin, but also student (and faculty) exchange opportunities and scholarships.20 In a competitive job market, familiarity with the Chinese language and culture is promoted as a plus for students, and hosting CIs are a way to meet growing local demand.21 In spite of criticism, such sentiments sometimes also extend to institutions that are not strictly educational in nature. In the U.K, for example, the Royal Zoological Society of Scotland sees the appointment of a native-speaking Chinese teachers as a way to educate people about conservation efforts (particularly for Panda habitats), and coincidentally connects Chinese language with science.22

Differences and Similarities in Purpose and Structure

As explained above, the U.S. approach to public diplomacy and language exchange in programs under BECA have their foundations in a hegemonic mindset. Originally intended as an informational service during wartime and invested in by those looking to expand the profits of U.S. corporations, public diplomacy is used to attract the “moths to the flame” — to engage local’s fascination with U.S. culture and imagery as a way to gain local support, and as a way to grease foreign relations.

CIs have very similar goals, but differ from most of their U.S. counterparts in design. Unlike their BECA and USIA counterparts, they are established as joint agreements between a local and a Chinese university. While BECA and the other remaining informational centers are based out of embassies and consulates under self-directed agencies and departments, CIs are much more directly controlled by the Chinese government in Beijing. That said, the CIs are as much about selling an idealized version of China as BECA programs are about engaging youths in target nations in order to spread U.S. values. Both are government programs that use language as a method of cultural exposure and exchange. Just as China intrumentalizes CIs to sway public opinion in other countries, U.S. cultural exchanges are part of foreign policy school of thought that seeks to change governments in other countries by promoting values like democratic elections and universal voting rights.23

Recommendations

U.S. universities should carefully examine Hanban policies and consider the benefits of having a CI on U.S. campus when submitting applications. It should be understood that universities with CIs are inviting an extension of a foreign government on their campuses. The most likely outcome, should any conflict arise, is that the CI will be closed and removed, but the implications of having CIs in the U.S. should be fully understood, and applicant institutions should be ready to negotiate and have legal counsel on hand. Ultimately, this issue should be raised to the state and federal government level, so that policies can be settled and schools can have the proper legal support should a greater conflict arise.

This is not to say that schools should not engage in cultural exchange with China by having a CI on campus, but they should do so with the knowledge that Chinese government control over CIs entails losing some control and intellectual freedoms. While the National Association of Scholars has recommended that all CIs be closed, they have alternatively suggested reform proposals that universities could present to their CI boards, including greater transparency, limitations on for-credit courses, and faculty orientation sessions for CI teachers and directors.24 Finally, universities must decide whether they want to surrender their rights to academic freedom, and if concerned, should seek out alternatives through exchange providers, direct university exchanges, or State Department and BECA programs.

While debates on the proper handling of Chinese education-based public diplomacy dominate the national conversation, recommendations for changes to U.S. education-based public diplomacy are sorely lacking. The casual approach to public diplomacy under the current administration is concerning for the future of international exchange. Importing foreign students in the hope that they will become ambassadors of the U.S. and promote U.S. values and ideas when they return home to countries like China demonstrates a certain naivety. By comparison, China has established a direct presence on U.S. campuses, using a well-funded and well-organized system that provides services to both local U.S. Students and Chinese international students alike. This imbalance in government support for cultural exchange should give pause for thought. The U.S. government might want to consider modifying its education-based public diplomacy to better protect its own systems and compete with new influencers.

1. Dizard, W. P. (2004). Inventing Public Diplomacy: the story of the U.S. Information Agency. Boulder, Colo.: Lynne Rienner.

2. United States Information Agency’s Office of Public Liaison, USIA Factsheet, 1999. Inventing Public Diplomacy, p. 20-23

3. United States Information Agency’s Office of Public Liaison. (1998). UNITED STATES INFORMATION AGENCY [Brochure], p. 8-9. http://dosfan.lib.uic.edu/usia/usiahome/overview.htm

4. CULL, N. (2010). Speeding the Strange Death of American Public Diplomacy: The George H. W. Bush Administration and the U.S. Information Agency. Diplomatic History, 34(1), 47-69,p 49-50. http://www.jstor.org.proxygw.wrlc.org/stable/24916033

5. United States Information Agency’s Office of Public Liaison. (1998). [Brochure], p. 7-9. http://dosfan.lib.uic.edu/usia/usiahome/overview.htm

6. Cull, 1999, op. cit. p. 60-64

7. United States Information Agency’s Office of Public Liaison, Binational Centers, 1999; Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs, Fulbright Commissions, 2017.

8. United States Information Agency Office of Public Liaison. (1999). USIA/USIS Direct English Teaching Programs. http://dosfan.lib.uic.edu/usia/E-USIA/education/engteaching/eal-elp2.htm

9. United States Information Agency Office of Public Liaison. (1999). Affiliated Programs. http://dosfan.lib.uic.edu/usia/E-USIA/education/engteaching/eal-elp3.htm

10. Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs. (2009, January). Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs Exchange Programs Non-U.S. Citizens. https://exchanges.state.gov/non-us.

12. Kennedy-Lugar Youth Exchange and Study Program. (2017). About Us. Retrieved December 12, 2017, from http://www.yesprograms.org/about/about-us.

13. Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs (n.d.) Fulbright Commissions, Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs.

14. Office of Chinese Language Council International (Hanban), About Us, 2014.

15. Office of Chinese Language Council International (Hanban), About Us, 2014; Asia Society, Asia Society. (2017). Asia Society Confucius Classrooms Network. https://asiasociety.org/china-learning-initiatives/asia-society-confucius-classrooms-network.

16.Office of Chinese Language Council International (Hanban). (2010, July 2). What are the functions of Confucius Institute Headquarters? http://english.hanban.org/article/2010-07/02/content_153906.htm

17. Office of Chinese Language Council International (Hanban) Application Procedure, 2014.

18. National Association of Scholars, & Peterson, R. (2017, April). Outsourced To China Confucius Institutes and Soft Power in American Higher Education (Rep.), p. 24-47. https://www.nas.org/projects/confucius_institutes

19. Peterson, R. (2017). American Universities Are Welcoming China’s Trojan Horse, in: Foreign Policy, May 9th, 2017. . Retrieved December 12, 2017, from 165-179.

20. National Association of Scholars, 2017, p.22.

21. Sheng, Yang: Confucius Institutes to better serve Chinese diplomacy. Global Times, January 24th, 2018.

22. Wang, M. (2018, March 6). Scottish university rejects criticism of Confucius Institute. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201803/06/WS5a9d8f41a3106e7dcc13fb7f.html

23. Morgenthau, Hans (1962). A Political Theory of Foreign Aid. The American Political Science Review, 56(2), 301-309. doi:10.2307/19523661962, p. 303

24. National Association of Scholars, 2017, p. 9-11