Robert Hunter, World Education Services

INTRODUCTION

The Islamic Republic of Pakistan is a culturally and linguistically diverse large South Asian country bordered by Afghanistan and Iran to the north and west, China to the northeast, India to the east and the Arabian Sea to the south. The Muslim-majority country was established in its current form after the partition of former British India into India and Pakistan in 1947, and the subsequent secession of Bangladesh, formerly known as East Pakistan, in 1971.

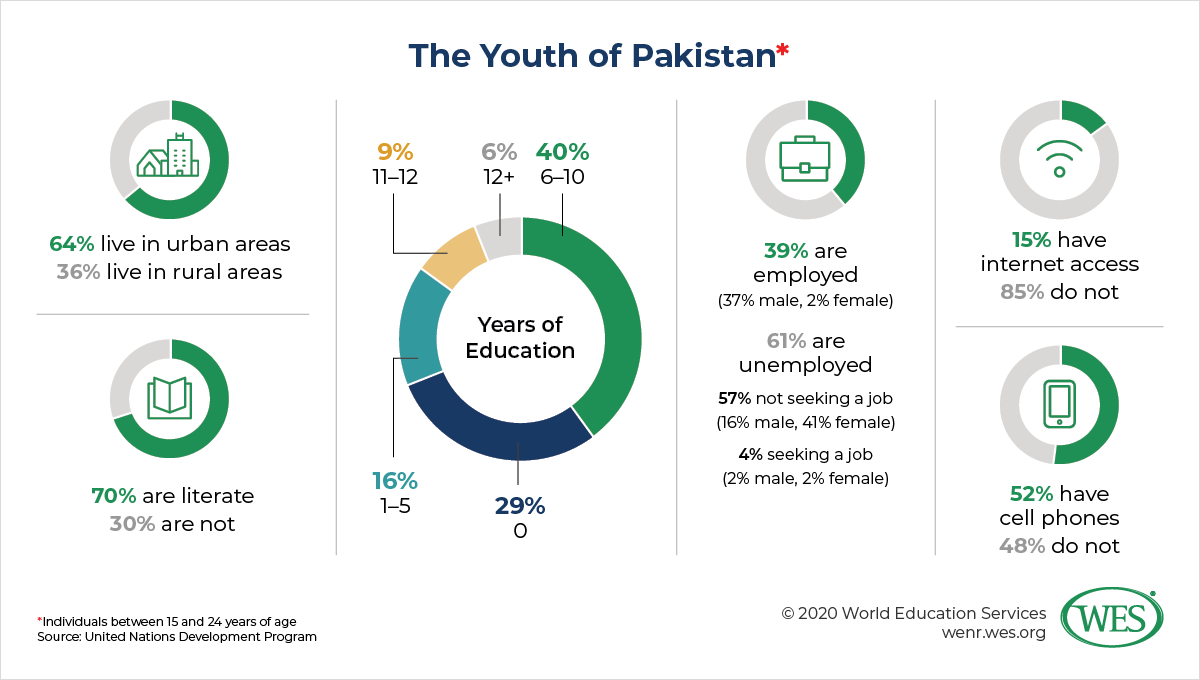

Currently the sixth most populous country in the world with 212 million people [2], Pakistan is characterized by one of the highest population growth rates worldwide outside of Africa. Even though the roughly 2 percent rate is now slowing, the country’s population is estimated to reach 403 million by 2050 (UN median range projection [3]). There are more young people in Pakistan today than at any point in its history, and it has one of the world’s largest youth populations with 64 percent of Pakistanis now under the age of 30. Consider that Karachi is projected to become the third-largest city in the world with close to 32 million [4] people by the middle of the century.

If Pakistan manages to educate and skill this surging youth population, it could harness a tremendous youth dividend that could help to fuel the country’s economic growth and modernization. Failure to integrate the country’s legions of youngsters into the education system and the labor market, on the other hand, could turn population growth into what the Washington Post called a “disaster in the making [6]”: “Putting catastrophic pressures on water and sanitation systems, swamping health and education services, and leaving tens of millions of people jobless”—trends that would almost inevitably lead to the further destabilization of Pakistan’s already fragile political system.

Given the poor state of Pakistan’s education system and its already rising youth unemployment rate [7], such fears are anything but unfounded. According to the Global Youth Development Index [8] published by the Commonwealth, a measure which uses the domains of civic participation, education, employment and opportunity, health and well-being, and political participation to gauge the progress of young people, Pakistan ranked only 154th of 183 countries, trailing sub-Saharan African nations like Sierra Leone or Ethiopia.

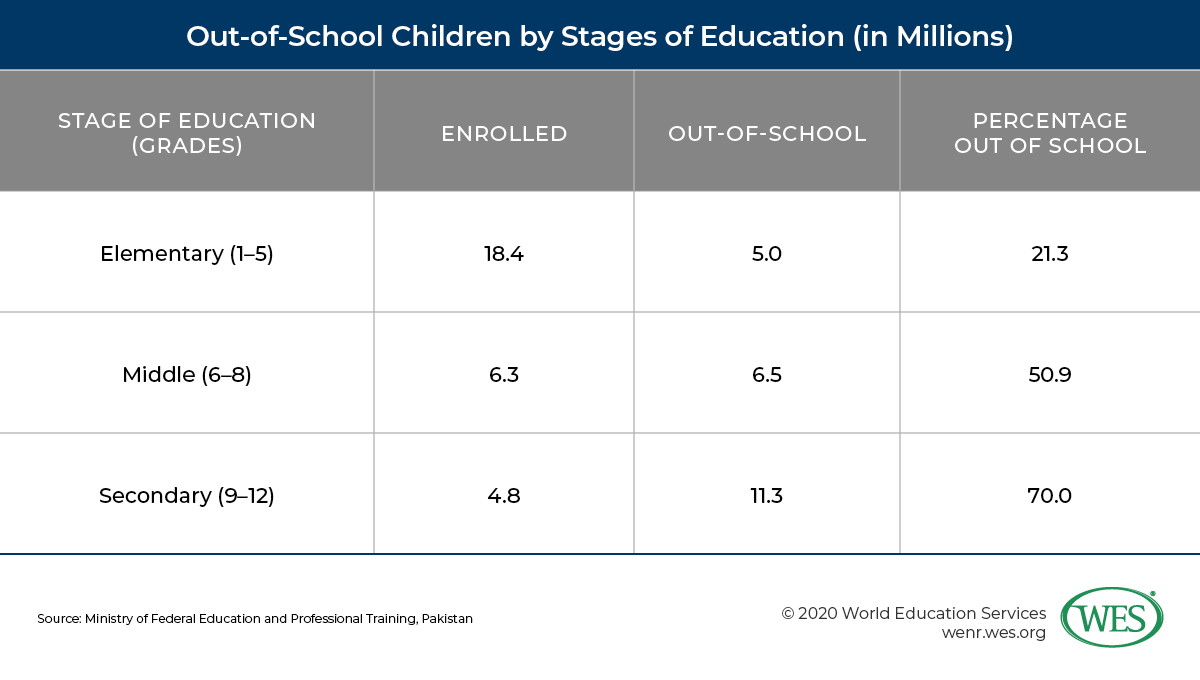

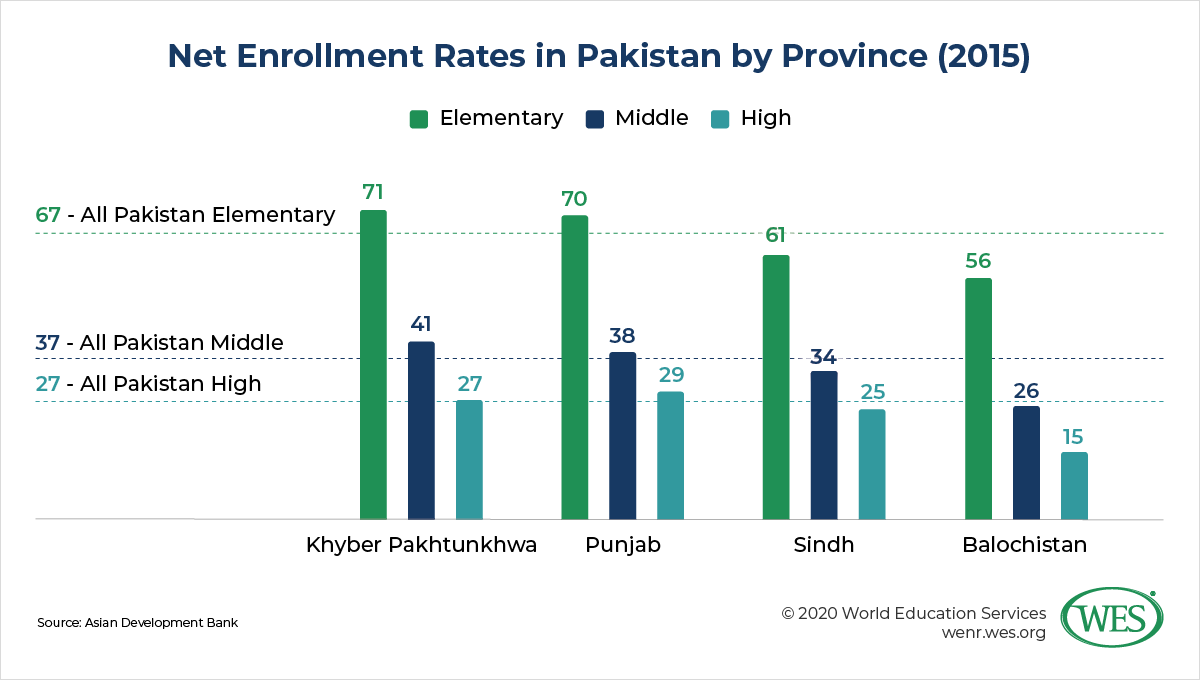

Perhaps most strikingly, Pakistan has the highest number of out-of-school children worldwide after Nigeria: Approximately 22.7 million [9] Pakistani children age five to 16—44 percent of this age group—did not participate in education in 2017. As shown in the table below, attrition rates increase substantially as children progress up the educational ladder.

This situation is exacerbated by striking inequalities based on sex and socioeconomic status. Gender disparities are rampant with boys outnumbering girls at every stage of education. According to Human Rights Watch [11], 32 percent of girls of elementary school age are out of school, compared with 21 percent of boys. By grade six, only 41 percent of girls participate in education, compared with 51 percent of boys. And by grade nine, merely 13 percent of young women are still enrolled in school.

The causes of these gender disparities are numerous. They include safety concerns, particularly in rural areas where students have to walk to school and rape of young girls is sadly not uncommon, as well as child marriage [12] and a culture that has historically undervalued the education of young women. Poverty also plays a major role. Families, particularly those in rural areas, often cannot afford the costs related to education. Here again the results are devastating, particularly for girls, who are frequently kept at home to cook and do housework so that both parents can work to keep the family afloat.

It’s crucial to understand that huge socioeconomic disparities [13] exist in Pakistan not only between rural and urban regions, but also between the country’s diverse provinces. These disparities have a big impact on educational outcomes, including vast gaps in access to education and overall educational attainment. While literacy rates in cities like Lahore, Islamabad, and Karachi are close to 75 percent [14], for instance, these rates can be as low as 9 percent in the “tribal regions” of Baluchistan, Pakistan’s largest and poorest province. Whereas 65 percent of fifth graders in Punjab province were able to read English sentences in 2018 [15], only 34 percent of fifth graders in Baluchistan [16] were able to do the same. The percentage of out-of-school children in the vast province with a small population spread over a large area—a fact that means that there isn’t a school within walking distance for many students—stands at an alarming 70 percent [17]. Conversely, in the urban and more affluent Islamabad Capital Territory, merely 12 percent of children are not in school.

Problems in Pakistani education are manifold. They range from dysfunctional and dilapidated school facilities that lack sanitation or electricity [19], to underqualified teaching staff, widespread corruption, and tens of thousands of “ghost teachers [20]” that sap public payrolls by not showing up for work. While most of these problems are worse at the elementary level, where most of Pakistan’s students are enrolled, they have ripple effects for the entire education system and depress enrollment rates at all levels. The gross enrollment rate (GER) in secondary education is as low as 43 percent before dropping down to 9 percent at the tertiary level—an extremely low percentage by global standards. To put these rates into regional perspective, the secondary GER in both India and Bangladesh is 73 percent, and as high as 98 percent in Sri Lanka (UNESCO statistics [21]).

Crucially, Pakistan devotes comparatively few resources to education and trails regional countries like India or Nepal in education spending. In 2017, Pakistan spent only 2.9 percent [22] of its GDP on education—far below the government’s official target of 4 percent [23]. Factors like declining economic growth rates, high levels of public debt, inflation [24], and budget shortfalls make it unlikely that this situation will improve in the near term and have, in fact, resulted in heavy-handed austerity in the education sector and elsewhere. It remains to be seen if the economic situation will improve [25] in the future and whether Pakistan can defuse its “population bomb” with inclusive economic development.

INTERNATIONAL STUDENT MOBILITY

Pakistan is a significant exporter of international students globally. According to UNESCO statistics [21], the number of outbound Pakistani degree-seeking students grew by 70 percent over the last decade, from 31,156 in 2007 to 53,023 in 2017. While that number is dwarfed by the more than 330,000 degree-seeking students from neighboring India, consider that Pakistan’s outbound mobility ratio—the percentage of international students among all students—is almost three time as high (2.7 percent in 2017) as that of India (1 percent). This means that it’s far more common for Pakistani students to study abroad and broaden their academic horizons in another country than it is for Indian students.

Further increases in student outflows from Pakistan are expected in the years ahead. The British Council, for instance, expects [26] Pakistan to be among the top 10 growth countries worldwide until 2027, despite an overall cooling of international student mobility on a global scale. For one, the precarious economic conditions and employment prospects in Pakistan are a major push factor for both international students and the hundreds of thousands of labor migrants leaving Pakistan each year [27]. Studying abroad can open immigration pathways in countries like Australia or Canada, while a foreign degree gives those that return a competitive edge on the Pakistani labor market.

Another important driver is the lack of university seats and high-quality study programs in Pakistan, particularly at the graduate level. While Pakistan has created a tremendous amount of new doctoral programs [28] over the past decade, growing numbers of Pakistani scholars are heading abroad to access higher quality education, primarily in fields like engineering and the sciences. To modernize research in Pakistan and raise the qualifications profile of university faculty, the government supports this development with scholarship programs of considerable scale, considering Pakistan’s fiscal constraints. While most Pakistani students are said to be self-funded [29], overseas scholarship programs have helped thousands of graduate students [30] to pursue studies in the United States, the United Kingdom, Cuba, Germany, France, and various other countries in recent years. Scholarship recipients are often required to return home after graduation.

The traditional English-speaking international study destinations, Australia and the U.S., are currently the top choices among Pakistani degree-seeking students, as per UNESCO [31] statistics. Data [32] published by the Australian government show that the number of Pakistani students grew almost threefold over the past decade, from 3,512 in 2008 to 10,000 in 2019, making Pakistan one of the top 10 sending countries of tertiary students in Australia [33].

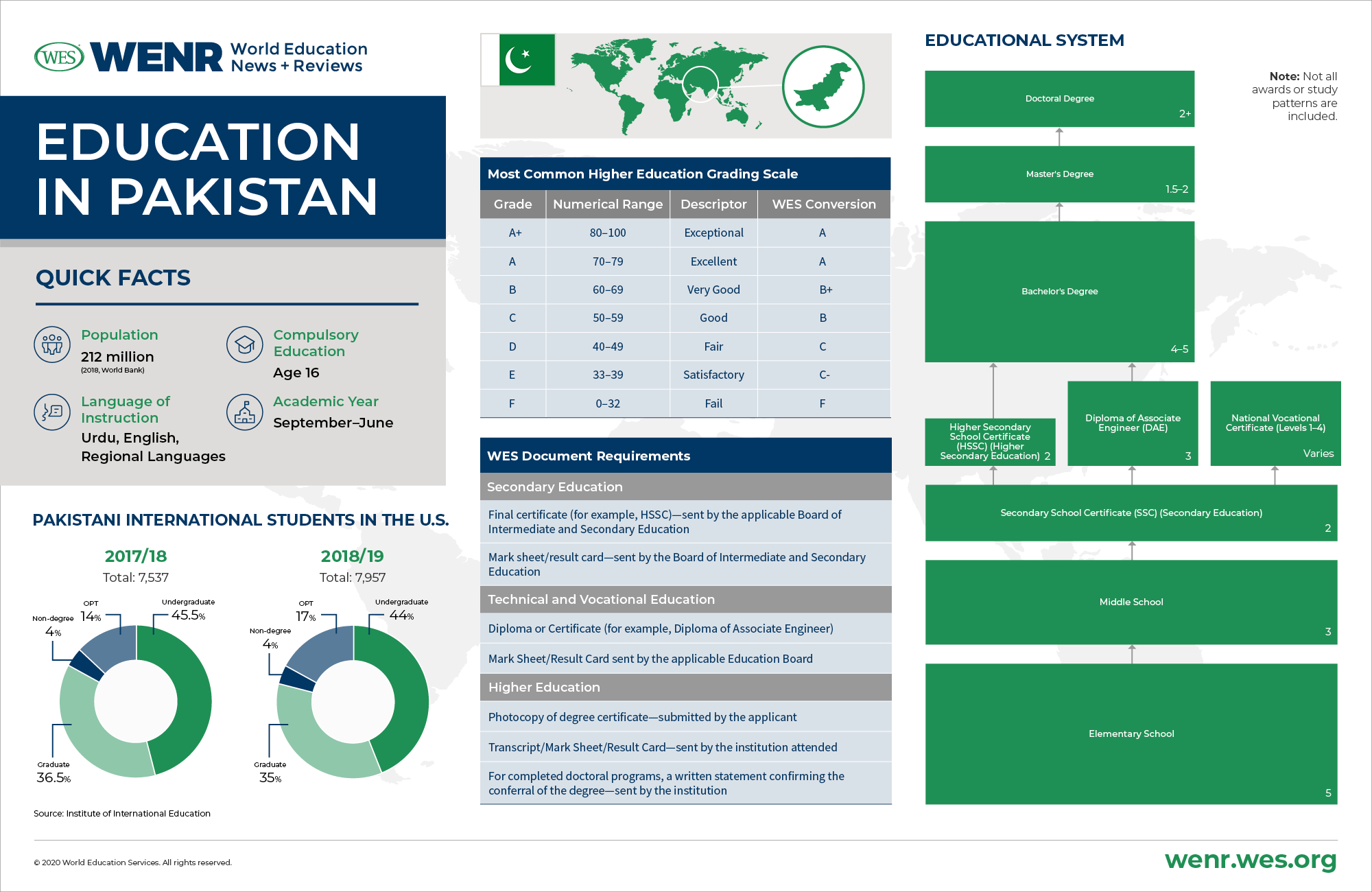

In the U.S., likewise, Pakistani enrollments have generally been on an upward trajectory over the past few years. According to the Open Doors data [34] of the Institute of International Education, Pakistan sent 7,957 students to the U.S. in 2018/19, an increase of 5.6 percent over the previous year, making it the 22nd most important sending country. Around 44 percent of these students are enrolled in undergraduate programs, 35 percent in graduate programs, and 4 percent in non-degree programs, while 17 percent pursue Optional Practical Training.

Other popular destination countries include the U.K. and the Muslim-majority countries Malaysia and Saudi Arabia, the latter also being a magnet for labor migrants from Pakistan. It should be noted, however, that China has emerged as a significant destination as well. China may, in fact, now host the largest number of Pakistani international students worldwide. While UNESCO does not report data for China, and Chinese government figures are difficult to compare,1 [35] Pakistan is currently the third-largest sending country to China with 28,000 students, per Chinese statistics [36]. As in neighboring India, many Pakistani students flock to China to pursue medical education—an underdeveloped and severely overburdened education sector in both India [37] and Pakistan [38]. Increased political and economic cooperation between Pakistan and China and Chinese scholarship funding likely play a significant role as well. Increasing numbers of Pakistani students are interested in learning Chinese [39].

In general, Pakistani students have increasingly diversified their international study destinations in recent years. In Canada, for instance, the number of Pakistani students has doubled over the past decade, if on a relatively small scale (4,050 students in 2019 [40]). Another notable destination country is Germany, where Pakistan is now among the top 20 sending countries after enrollments jumped by 28 percent within just one year, from 3,836 in 2017 [41] to 4,928 in 2018 [42]—a trend likely driven, among other factors [43], by the availability of tuition-free, high-quality graduate programs in engineering.

The increased demand among Pakistani youths for an international education is also reflected in surging enrollments in transnational TNE program offerings by academic institutions from various countries in Pakistan itself. Examples include the Karachi branch campus [44] of the Irish Griffith College, and TNE programs in accounting [45] offered by the British Oxford Brookes University in collaboration with the Association of Chartered Accountants (ACCA). In 2018, there were 40,210 students studying wholly in Pakistan for U.K. qualifications [46], making Pakistan the fourth-largest British TNE market worldwide [45].

Inbound Student Mobility

Given Pakistan’s political instability, weak economy, and the shortcomings of its higher education system, Pakistan is not a significant destination country for international students. That said, there are sizable numbers of international students from Muslim-majority developing countries like Somalia, Sudan, Yemen [47], and, most notably, neighboring Afghanistan [48], who pursue studies in Pakistan, where they can access education of higher quality than they can at home.

Pakistan has taken in vast numbers of refugees from war-torn Afghanistan over the past decades and is still hosting some 2.4 million Afghan refugees [49]. While the integration of these refugees into Pakistan’s already overburdened and dysfunctional school system is a huge challenge [50], Pakistani authorities have undertaken at least some efforts to provide Afghans with access to higher education. In 1999, the Afghan University in Peshawar, known today as Shaikh Zayed University, was set up specifically to educate Afghan students. Most recently, Pakistan’s Higher Education Commission in 2019 announced that it will provide 3,000 scholarships [51] for students from Afghanistan to pursue studies at Pakistani HEIs in fields like medicine, engineering, agriculture, computer science, and business management.

There are also sizable numbers of international students from various countries coming to Pakistan to study at Islamic universities or madrasahs. That said, most international madrasah students come from neighboring Afghanistan as well [52].

IN BRIEF: THE EDUCATION SYSTEM OF PAKISTAN

Pakistan’s education system has evolved substantially from both its Islamic and British historical roots. It has improved greatly in the 20th and 21st centuries, but still tends to rely too heavily on rote memorization and outdated teaching and examination methods. While great strides have been made in improving literacy [53] and participation rates, the education system remains largely elitist with access to the best educational opportunities available only to the more affluent or well-connected.

In recent years, Pakistan has adopted increasingly modern methods of teaching and examination and has, following global trends, moved to a 12+4+2 structure. On the other hand, Islamic traditions remain very much alive in a society that is up to 96 percent [54] Muslim, the majority of them Sunnis. Islamiyat (Islamic studies) is a core subject up through lower-secondary school and is seen as critical to the inculcation of Islamic values in both personal development and the formation of a national identity. Civics has recently been introduced in school curricula in place of Islamiyat for religious minority populations.

Administration of the Education System

Pakistan is a federation composed of four provinces, the capital territory of Islamabad and the two autonomous regions of Azad Jammu and Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan. The four provinces are Baluchistan, Punjab, Sindh, and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, which was until 2010 known as the North-West Frontier Province. Punjab, the most populous province, is home to more than 50 percent of Pakistan’s population. Sindh is the second most populous province; it contains the crowded metropolis Karachi, one of the world’s largest cities proper with some 15 million people. On the other hand of the spectrum, Baluchistan is a vast, sparsely populated, and mountainous province of approximately 12 million people [55].

While Pakistan had a comparatively centralized system of government throughout much of its history, there has been a trend toward decentralization since the early 2000s, notably in education. While matters like the development of school curricula used to be a shared responsibility of the federal and provincial governments, many of these responsibilities have now been delegated to the provinces [56]. Within the provinces themselves, the administration of education largely shifted from provincial governments to local district governments [57].

While most aspects of early childhood, elementary, and secondary education are now administered at the provincial level, the Ministry of Federal Education and Professional Training (MFEP) [58] in Islamabad continues to set overarching education policies and quality standards. It also coordinates education policies between jurisdictions. While there can be considerable differences in school curricula between provinces, overall curriculum guidelines are determined by the MFEP. As discussed below, the current administration of Prime Minister Imran Khan also seeks to achieve greater standardization by introducing a common national school curriculum [59].

The federal government has primary oversight of both higher education and technical and vocational education (TVET). The main federal oversight body in higher education is the Higher Education Commission (HEC [60]), a constitutionally established autonomous institution responsible for the regulation, accreditation, and funding of higher education in the country.

Of note, Pakistan also has an extensive system of madrasahs, or religious seminaries, which has grown explosively [61] over the past decades, particularly in rural areas. These schools operate either wholly autonomously or are affiliated with private madrasah education boards. The federal government in 2001 created a national Pakistan Madrasah Education Board to compete with the existing private boards and create model Islamic seminaries throughout the country. But it appears to have been mostly unsuccessful [62] in bringing about greater standardization at these institutions. However, there are now renewed plans to bring madrasahs, several of which are funded by Saudi Arabia (Sunni schools) and Iran (Shia schools), under government control. These plans are partially driven by international pressure [63] and concerns about political radicalization (see the section on madrasah education below).

Intermediate and Secondary Education Boards

Each of Pakistan’s provinces and the territories under control of the federal government have their own Boards of Intermediate and Secondary Education (BISE) that conduct graduation examinations at the lower-secondary and upper-secondary levels. In total, there are 28 public exam boards across Pakistan’s provinces and jurisdictions. In addition, there are two private boards that offer intermediate and secondary examinations throughout the country—the Aga Khan University Examination Board and the recently established Ziauddin University Examination Board.

Affiliated with each of these boards are schools that teach the board-prescribed curricula and prepare students for the intermediate and secondary exams. To become affiliated with a BISE, schools need to meet certain quality criteria set by the individual boards. Under certain conditions, independent “private candidates” may also be allowed to sit for the exams without attending affiliated schools.

For the most part, the examination certificates issued by the different boards are recognized by higher education institutions, government institutions, and employers nationwide. Examinations, including those of the private boards, are based on national curriculum guidelines. A steering body attached to the MFEP—the Inter Board Committee of Chairmen [64]—coordinates curricula and examination-related matters between the different boards.

There are also a number of international, predominantly British, examination boards in Pakistan, such as Cambridge Assessment International Education [65]. Note, however, that the expensive private prep schools that teach British curricula like the Cambridge International General Certificate of Secondary Education (IGCSE) cater mostly to wealthy elites and are out of reach for most ordinary Pakistani households.

Academic Calendar and Language of Instruction

Higher education institutions (HEIs) generally follow a semester system—two semesters of 16 to 18 weeks that run roughly from January through May and then August through December. While some variations in structure exist, the HEC has recently put forth overall guidelines [66] for the implementation of a uniform semester system for HEIs.

The academic calendar in elementary and secondary schools runs roughly from February through June and September through January with a break that coincides with monsoon season.

While there are more than 70 languages spoken in Pakistan, including the provincial languages Punjabi, Pashto, Sindhi and Balochi, the country’s official languages are Urdu and English. English has been the main language of instruction at the elementary and secondary levels since colonial times. It remains the predominant language of instruction in private schools but has been increasingly replaced with Urdu in public schools. Punjab province, for example, recently announced that it will begin to use Urdu as the exclusive medium of instruction in schools beginning in 2020. [67] Depending on the location and predominantly in rural areas, regional languages [68] are used as well, particularly in elementary education. The language of instruction in higher education is mostly English, but some programs and institutions teach in Urdu.

ELEMENTARY AND MIDDLE SCHOOL EDUCATION

Education in Pakistan is free and compulsory for all children between the ages of five and 16, or up through grade 10, or what’s referred to as “matriculation” in Pakistan. It is a fundamental right accorded by Article 25 A of the constitution. However, as noted, participation in compulsory education is far from universal, particularly in socioeconomically disadvantaged regions. According to UNESCO, the overall elementary NER in Pakistan stood at only 68 percent [21] in 2018. While enrollment ratios in some major cities are close to universal, Pakistan has 22.7 million [9] out-of-school children (OOSC), as mentioned earlier. Five million of these are at the elementary level, and the numbers only increase at the middle and secondary school levels.

Most Pakistani children that participate in education enter school at the age of five. Early childhood education (ECE) for children between the ages of three and four has historically been given little attention even in more affluent urban areas, where patchy public provision may be supplemented with private kindergartens. The Pakistani government estimates [70] that only about a third of children between the ages of three and four participate in formal early childhood education. Both the federal and provincial governments are seeking to increase ECE participation rates, but progress is slow. Enrollment ratios have remained largely stagnant [71] in recent years.

Elementary education is five years in length (grades 1 to 5), followed by three years of middle school (grades 6 to 8), and four years of secondary education, divided into two years of lower-secondary and two years of upper-secondary education (5+3+2+2).

Private education features prominently in Pakistani elementary and middle school education, as it helps to bridge capacity gaps in the underfunded public sector. Some 35 percent of all pupils in elementary schools are enrolled in private schools, according to official statistics [70]. Many elementary schools in Pakistan suffer severely from a lack of quality including in terms of infrastructure. Recent government figures [70] bring this into focus—merely 54 percent of elementary schools have electricity, 67 percent have drinking water, and 68 percent have latrines. A lack of trained teachers and teacher absenteeism are the other most often cited problems.

The elementary curriculum typically includes Urdu, English, regional languages, mathematics, science, social studies, and Islamiyat. The middle school curriculum features the same subjects as the elementary curriculum, but additional languages like Arabic or Persian may be introduced. It should be noted, however, that considerable variations in curricula may exist between jurisdictions, especially since the administration of the school system devolved from the federal government to the provinces in 2010. This move, while placing decision-making and funding into the hands of those with a greater understanding of local needs, has also created a fragmented system that lacks coordination and has produced uneven educational outcomes in different provinces.

The provinces of Punjab and Sindh have in recent years introduced standardized province-wide examinations at the end of grades 5 and 8. Other provinces are experimenting with comparable examinations, but practices vary across Pakistan. Depending on the jurisdiction, pupils who complete grade five may be allowed to progress into middle school without sitting for provincial exams. The overall transition rate from elementary to middle school stood at 84 percent nationwide [9] in 2017.

Efforts to Create a National Curriculum

The government of Prime Minster Imran Khan seeks to reduce the fragmentation and inequalities of Pakistan’s school system and create a modernized “uniform education system.” A National Curriculum Committee (NCC) has been tasked with coordinating standards between provinces and developing a Single National Curriculum (SNC) [72] for school education—a project scheduled to be completed by October 2020 for grades 1 to 8, by December 2021 for grades 9 and 10, and by December 2022 for grades 11 and 12. Critics, however, consider a uniform school system unrealistic, given the vast economic, linguistic, and religious disparities between Pakistan’s regions. Prominent Pakistani academic Pervez Hoodbhoy, for instance, noted that it isn’t feasible to teach students in remote rural regions like the federally administered tribal areas the same curriculum taught in rich urban neighborhoods in Karachi [73].

SECONDARY EDUCATION

Pakistan has a secondary education system centered on high-stakes examinations and rote learning. In British India, the structure and curricula of secondary education were mandated by British colonial rule and culminated in examinations administered by British education boards. As mentioned earlier, after independence, Pakistan then developed its own Boards of Intermediate and Secondary Education (BISE) which were tasked with developing and conducting final examinations at the ends of grades 9 to 12.

Admission to secondary education requires completion of middle school (grade 8) as well as a passing score on provincial grade 8 examinations, depending on the jurisdiction. About 68 percent of students at the lower-secondary level and 88 percent at the upper-secondary level attended public schools in 2017 [23]. Even so, private education at the secondary level is growing, with enrollment in private institutions significantly more common in more affluent urban areas, where enrollments in private schools can account for as much as 60 percent [23] of all enrollments.

Secondary education consists of two years of lower-secondary education (grades 9 and 10) followed by two years of upper-secondary education, typically called intermediate education (grades 11 and 12). There are three different specialization streams in lower-secondary education: science, humanities, and technical. Students typically elect three specialization subjects from one of these streams (for example, economics, geography, and business studies in the humanities stream). In addition, the curriculum includes a range of mandatory core subjects, generally Urdu, English, mathematics, Pakistan studies, and Islamic studies (ethics for non-Muslim students).

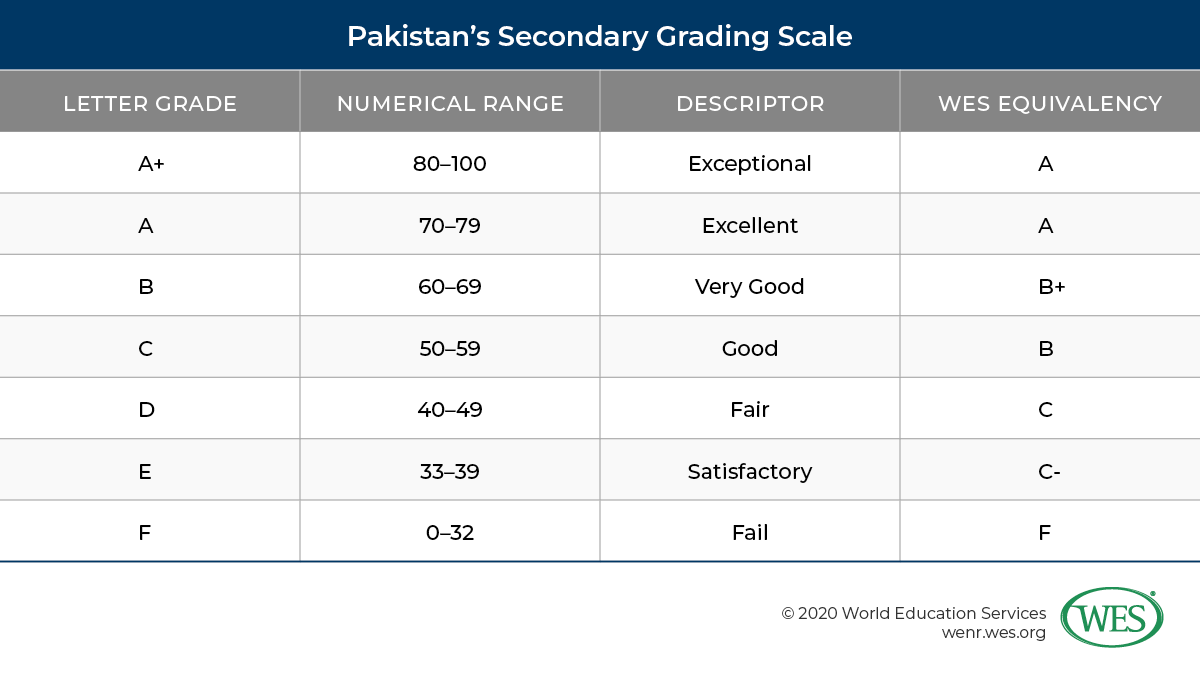

The Secondary School Certificate (SSC), also referred to as “matriculation certificate,” is examined in two parts at the end of grades 9 and 10 and is awarded upon passing the final SSC exam at the end of grade 10. The exam is graded on the 0-100 scale shown below. The minimum passing grade in each subject is 33 percent. The final grade average is typically converted into a letter grade.

Students are most commonly examined in eight subjects. Those who fail more than two subjects must repeat the school year. In 2019, the overall pass rate in the SSC exams of the Federal Board of Intermediate and Secondary Education was 84 percent [74], whereas the pass rate for the private Aga Khan University Examination Board was 96 percent [75] with 46 percent of test takers achieving an overall grade of A or above.

A passing score on the SSC examinations is required to progress to higher secondary education, which is two years in duration (grades 11 and 12) and provided by upper-secondary schools or so-called intermediate colleges, most of them public institutions. Only a small fraction of Pakistanis participate in upper-secondary education—merely about a quarter of students transition from grade 10 to grade 11 [23]. According to UNESCO [21], the overall upper-secondary NER in Pakistan was 23 percent in 2017, compared with 38 percent in Nepal and 46 percent in Bangladesh.

There are seven groups or streams available in higher secondary education, including general, humanities, science, pre-medical, pre-engineering, medical technology, and home economics. Compulsory subjects include Urdu, English, Islamic education (civics for non-Muslim students), and Pakistan studies along with both required and elective courses in the specific stream. For example, science group students typically take chemistry, physics, and mathematics; those in the pre-medical group take biology, physics, and chemistry.

Like the SSC exam, the Higher Secondary School Certificate (HSSC) examination (also referred to as “intermediate exam”) is administered in two parts at the end of grades 11 and 12. The exams are conducted by one of the Boards of Intermediate and Secondary Education (BISE). The grading scale and minimum passing requirements are the same as in the SSC exams.

Madrasah Education

Islamic religious education has and continues to play a prominent role in Pakistan. Originally relatively small in number (less than 200 at independence) with a mission to educate religious leaders, madrasahs have grown to a number [63] conservatively estimated at over 30,000. Estimates on the number of students enrolled in these schools vary greatly but range anywhere from 1.8 million [77] to 3.5 million [78]. Among the factors driving this growth are the shortcomings of the public school system, particularly the lack of schools in rural areas, and the influx of Afghan and other refugees, which are often excluded from Pakistan’s formal education system. Funding and support from other countries, including Saudi Arabia and Iran, also play a role.

While most madrasahs are unregistered institutions that provide an almost exclusively religious education, focusing on studying the Koran and Arabic and Persian languages, others are formally affiliated with madrasah examination boards and incorporate the compulsory subjects of the national school curriculum. The qualifications awarded by these institutions are examined by the madrasah boards. They include certificates equivalent to the completion of middle school, secondary school (shahadatul sanvia aama), and higher secondary school (shahadatul sanvia aama)—credentials that are formally considered on par with SSC and HSC exams by government authorities. The HEC also recognizes [79] some post-secondary madrasah qualifications (shahadatul alia (12+2), shahadatul almiya (12+2+2), and some others) as equivalent to bachelor’s and master’s degrees in Arabic and Islamic studies.

That said, ongoing efforts to “mainstream” Islamic education and bring religious seminaries under greater government control constitute a challenge and continue to face resistance [80] from many unregistered madrasahs. In a recent development [81], the MFEP announced that madrasah students will sit for federal board examinations and study the national curriculum by 2020 as part of the government’s drive to establish a uniform education system across Pakistan. Given the complex and historically autonomous nature of religious education in the country, however, only time will tell if these reforms will take hold.

TECHNICAL AND VOCATIONAL EDUCATION (TVET)

Given that Pakistan is witnessing the largest population growth of youth in its history, with two-thirds of the population projected to be below the age of 30 for the next three decades, TVET is seen as perhaps the most critical education sector to address unemployment and develop a workforce capable of driving economic development.

TVET in Pakistan is provided in various forms, from informal industry-based apprenticeship programs to secondary-level skills certificate and diploma programs of one or two years, as well as 10+3 programs that straddle secondary and post-secondary levels. Examples of the latter include the 10+3 Diploma in Nursing and Diploma of Associate Engineer (DAE)—qualifications that are examined by state boards of technical education and boards of nursing education. These qualifications provide graduates access not only to specialized employment but also to tertiary education programs, given that the curricula typically include the compulsory subjects of the national upper-secondary curriculum. Completion of the DAE, for example, enables students to enter directly into applicable Bachelor of Technology programs. In addition, there are several post-secondary diploma and certificate programs in various occupations that are awarded by state boards of technical education.

TVET programs are taught at technical secondary schools, trade schools, polytechnics, and technical colleges, most of them public institutions. In 2018 [82] there were more than 3,600 vocational and technical institutions in the sector enrolling over 400,000 students, most of them concentrated in cities and population-rich provinces like Punjab and Sindh. This represents a significant increase from 2013 when there were 1,650 institutions with approximately 315,000 students. Despite this growth, the TVET sector accommodates less than 15 percent of the nearly three million young people who enter the job market each year. The government is currently trying to create a system with the capacity to accommodate 20 percent [83] of all school leavers by 2025.

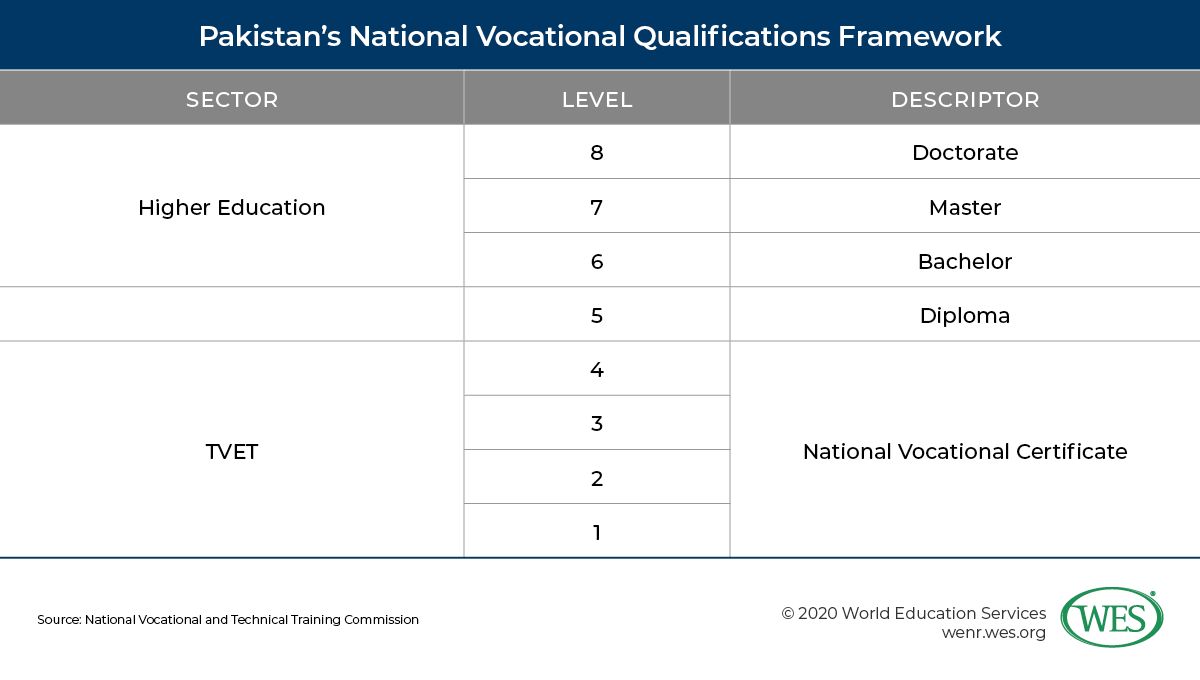

Beyond its capacity shortages, the TVET sector has historically been marred by a lack of national coordination, quality problems, and outdated curricula that fail to adequately serve the needs of the labor market. To improve this situation, a process to develop a National Vocational Qualification Framework (NVQF) was initiated in 2009 in collaboration with and funded by the European Union (EU) and the governments of the Netherlands, Norway, and, perhaps foremost, Germany, with its internationally recognized TVET system. The goal is to create a system of competency-based, nationally standardized TVET qualifications that are aligned with international standards.

The National Vocational Qualification Framework (NVQF)

The NVQF is currently in development but will eventually span eight levels of qualifications as shown below. Already established are levels 1 to 4, which define secondary-level national vocational certificates (NVCs) designed to produce semi-skilled workers in a wide variety of vocations, ranging from automotive technicians to electrician or plumber. While admission to these programs generally requires the Secondary School Certificate, there are various pathways to obtain an NVC. They can be earned by completing formal training programs or non-formal industry-based training, or even through self-learning during employment. All pathways culminate in a skills assessment based on national competency standards conducted by provincial qualification assessment boards, trade testing boards, or other certified assessors. Skills standards [84] are developed at the national level by a Qualification Development Committee that is overseen by the National Vocational and Technical Training Commission (NAVTTC) [85].

To ensure the comparability of qualifications, they are being standardized in a variety of ways. The level descriptors [86] delineate qualifications of increasing complexity in terms of skills, as well as levels of responsibility, from functions that require supervision (level 1) to the ability to perform with full autonomy (level 4). In the near future, only officially registered qualifications may use the “national” designation in the qualification title. Titles of qualifications must also include the type (certificate or diploma) and the occupation (for example, National Vocational Certificate Level 1 in Hospitality). A registry of qualifications is being developed but does not appear to be available publicly as of this writing. TVET qualifications at level 5 (mostly 10+3 technical board diplomas like the DAE) through level 8 (TVET qualifications at the tertiary level) will eventually be defined and incorporated into the framework as well.

HIGHER EDUCATION

Pakistan has a relatively young higher education sector. At the time of partition, the country had only one university which had less than 1,000 students enrolled—the University of the Punjab in Lahore. Since then, increased participation rates in elementary and secondary education, as well as the surging youth population growth of recent years, have led to a rapid expansion of the system. Tertiary enrollments spiked from only 305,000 in 1990 to 1.9 million in 2018, according to UNESCO [21]. There are currently 209 [88] recognized degree-awarding institutions (DAIs), up from 59 in 2001 and 139 in 2010. The majority of HEIs and tertiary students are clustered in the province of Punjab.

Despite this growth, however, overall participation rates in tertiary education remain extremely low in Pakistan: The country’s tertiary GER stood at only 9 percent [21] in 2018, compared with 29 percent in neighboring India and 21 percent in Bangladesh.

Government funding for public higher education, which accounts for about 70 percent [89] of operating costs, is vastly insufficient, especially in light of Pakistan’s debt crisis [90] and recent austerity budgets [91]. The government of Prime Minister Imran Khan, inaugurated in 2018, cut the higher education budget by 37 percent in 2019, while holding back funds previously allotted to the HEC [92]. As a result of these cuts, some public universities had to slash their graduate programs [93] and are unable to pay salaries and pensions [94]. In an attempt to curb expenditures, public universities in the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa have recently been barred from admitting [93] new students altogether.

Overall education spending, including expenditures related to the school system, is low even by South Asian standards. Consider that Pakistan in 2017 spent only 2.9 percent of its GDP on education, whereas Nepal allocated 5.1 percent [95]. India, by comparison, spent 4.6 percent of its GDP on education in 2016. While Pakistan’s current National Education Policy of 2017 [96] calls for spending to increase to 4 percent, expenditures on education are estimated to have actually decreased to 2.4 percent of GDP in 2018/19.

As in other critically underfunded systems, this lack of resources negatively affects the quality of Pakistani HEIs. Beyond the dearth of funds, many observers note that the efficiency of the Pakistani system is also undermined by poorly managed top-down governance structures, a lack of qualified faculty and cooperation between institutions, red tape, comparatively high levels of corruption, and patronage networks in which positions are filled based on political allegiances rather than objective qualifications.

While Pakistan has made good strides in improving the quality of its institutions over the past decades, it needs to significantly strengthen its higher education system to nurture the human resources needed for the development of a modern knowledge-based economy. In 2017 the Global Human Capital Index [97], which measures how well countries develop their human capital, ranked Pakistan 125th out of 130 countries, representing 93 percent of the world’s population.

University Admissions

Undergraduate admissions criteria in Pakistan vary by institution, but the HSSC/Intermediate Examination Certificate is nearly always required, although applicants may sometimes also be admitted based on technical board diplomas, depending on the program. A minimum grade average of 50 percent or above (second division pass) is required by most institutions, but the threshold in more competitive disciplines like engineering and medicine is usually higher (at least 60 percent). Since upper-secondary education programs are offered in different streams, an HSSC in a stream related to the intended major is a typical requirement as well.

Additionally, applicants may have to sit for admission tests or interviews, especially at top-tier institutions. Most typically, this is an internal assessment devised by the institution, but it’s increasingly common for institutions to rely on external tests, such as the National Aptitude Test [98] conducted by Pakistan’s National Testing Service. Some private institutions may also accept foreign tests, such as the U.S.-based SAT. Applicants who’ve earned secondary credentials outside of Pakistan must obtain an equivalency certificate from the Inter Board Committee of Chairmen to be considered for admission [99]. It should be noted that colleges or teaching institutions in the public sector are bound by the admission requirements set by the degree-awarding university to which they are affiliated.

Types of Higher Education Institutions

Like neighboring India, Pakistan has a higher education system made up of relatively few degree-granting universities but close to 3,000 colleges and other teaching institutions that are affiliated with these universities. Authorized DAIs are mostly chartered universities but also include research institutes or military academies. DAIs can be either public or private and are approved (chartered) by the federal or provincial governments based on the recommendations of the Higher Education Commission [100] (HEC).

Affiliated colleges, on the other hand, are regulated at the provincial level. They can also be either public or private, but only public DAIs are allowed to have affiliated colleges, and most colleges are, in effect, public institutions. Relying on affiliated colleges to teach degree programs affords universities a comparatively easy and cost-effective way to scale up capacity, especially in remote areas. The number of affiliated colleges in Pakistan has consequently mushroomed since the 1990s.

Even so, access to colleges remains heavily skewed toward urban areas. What’s more, since even public colleges are to some extent dependent on tuition fees, many only offer programs in popular fields of study that don’t require large investments in facilities. As noted in a recent HEC-sponsored study [101], “science subjects … are avoided by colleges because there is need of science laboratories to run those programs. … There is little interest of affiliated colleges to have research-oriented courses. Again it may increase their cost to hire those faculty who can conduct quality oriented research science programs that require lab facilities.”

To become affiliated with DAIs, colleges must meet certain minimum requirements [102] set forth by the HEC and the affiliating university, which determines the syllabi, conducts periodic examinations—including annual progression exams and graduation exams—and awards the final degree. Colleges may offer a range of more general programs in arts and sciences, whereas others are mono-specialized in disciplines like business administration, education, or engineering. While it is the norm for a college to affiliate with just one DAI, some—particularly those with more diverse general programs of study—may be affiliated with more than one institution. The HEI with the most affiliated colleges is the University of Punjab with more than 600 colleges. Overall, there are now about 2,900 affiliated colleges [103] in Pakistan.

In addition to affiliated colleges, there’s a smaller number of constituent colleges, also referred to as campuses, directly administered by the universities. Whereas most affiliated colleges teach only undergraduate programs, these colleges offer both undergraduate and graduate programs.

A relatively new phenomenon is the establishment of a system of community colleges. Like other colleges, community colleges are teaching institutions affiliated with a DAI, but they are designed to offer more applied programs that lead to employment-geared associate degrees. One example of this trend is a pilot program [104] launched by the Punjab Higher Education Council to establish a number of community colleges to address the need for skilled labor in the province.

Universities

Of the 209 DAIs/universities recognized by the HEC, 126—or 60 percent—are public. Private higher education is relatively new in Pakistan and was, in fact, banned under leftist governments in the 1970s and early 1980s. After it was re-introduced, the number of private HEIs grew substantially, helping to absorb the rising demand for higher education. While there were only two private HEIs in Pakistan at the beginning of the 1990s, there are now 83 private DAIs, enrolling some 19 percent [103] of all university students.

It should be noted, however, that the future growth potential of private higher education in Pakistan is limited by what the market is able to bear, particularly with regard to expensive higher quality institutions, many of which require tuition fees that are out of reach for most of Pakistan’s population. The fees charged by private HEIs vary greatly by institution but can be as high as 480,000 rupees [105] (USD$3,106) per semester. By comparison, semester fees at public institutions are relatively nominal, averaging 60,000 to 90,000 rupees (USD$390 to USD$585). (For context, Pakistan’s gross national income per capita was USD$1,590 in 2018 [106]).

Prestigious private institutions like Aga Khan University and the Lahore University of Management Sciences, Pakistan’s first private universities, are among the country’s top institutions. However, many private providers are smaller, specialized, market-oriented institutions of lesser quality [107] that mainly offer programs in fields like business management and information technology. Private institutions offer fewer graduate programs than public HEIs, and many don’t engage in academic research activities.

Most public universities, by contrast, are large multi-faculty research institutions that offer a full range of academic programs, including PhD programs, which are almost exclusively [103] offered by public DAIs. The University of the Punjab has five campuses, more than 70 departments, and about 46,000 on-campus students [108]. Pakistan’s largest public university in terms of enrollments, and simultaneously one of the largest universities in the world, is Allama Iqbal Open University, an open distance education provider with 1.4 million students [109].

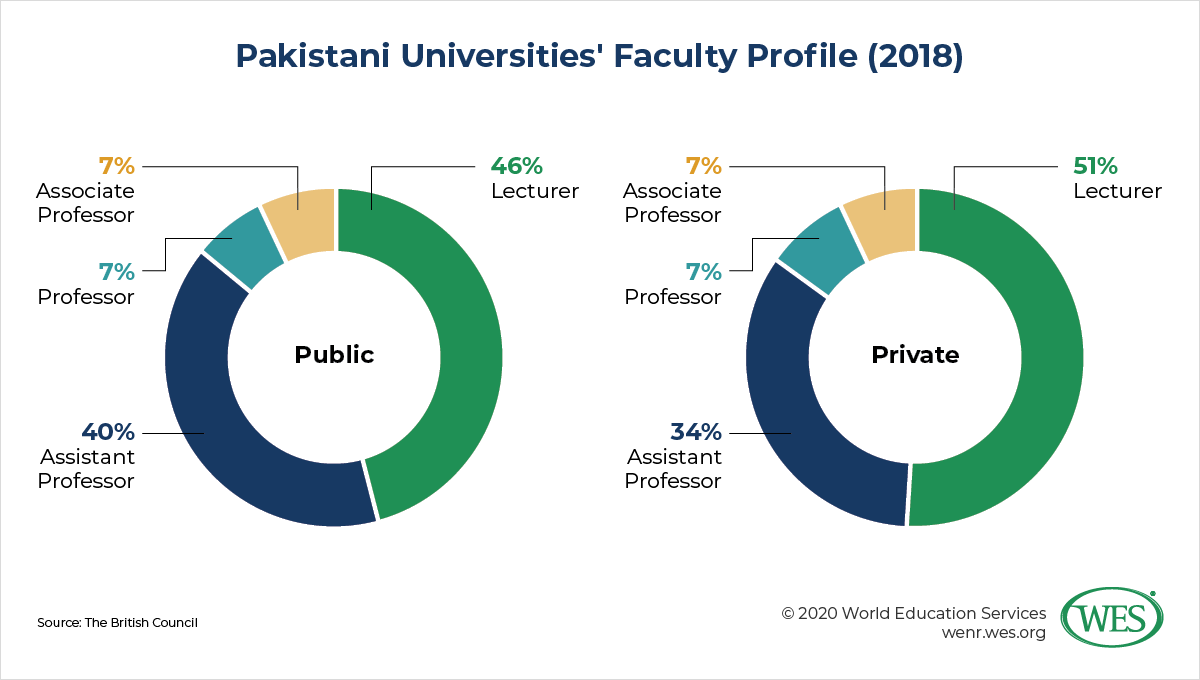

Faculty and Research Output

Among the most pressing shortcomings of Pakistani universities is a shortage of senior teaching staff. While assistant, associate, and full professors must formally have a PhD, entry-level lecturers in most academic disciplines except engineering, information technology, computer science, medical sciences, law, and studio arts and design can teach with just a master’s degree [110] (18 years of total education). Since HEIs rely heavily on non-tenured lecturers, the percentage of teaching staff with PhDs is consequently low. According to HEC statistics, only 21 percent [111] of full-time faculty at Pakistani universities held a PhD in 2015. Some universities did not have any [111] professors who held doctoral qualifications.

The research capacities of Pakistani universities are another issue of concern. While research output has grown phenomenally [113] in recent years, resulting in Pakistan now producing more academic journal publications in natural sciences than countries like Malaysia or Indonesia [114], the overall quality of the research is questioned by many observers [115]. Much of the rapid growth in Pakistan’s research output is owed to an incentivization system that ties academic journal publications to faculty promotions and financial rewards. As a result, the system is said to be rife with corruption, plagiarism, and fabricated research, with many publications allegedly produced for purely material gains [116]. Indicative of such problems, the HEC in 2017 closed down more than 100 doctoral programs [117] over quality concerns.

To improve the quality of Pakistani universities, the HEC currently plans to create a three-tiered system [118] of HEIs, including a top tier of 30 government-supported research universities that will cater to Pakistan’s best and brightest students. The other two tiers comprise the remainder of DAIs (tier 2) and affiliated colleges (tier 3). By 2025, the number of tier 1 and 2 university-level institutions is projected to increase from 209 today to 300, serving more than seven million students.

Quality Assurance and Accreditation

Both public and private HEIs are authorized to operate by the federal or provincial governments based on the approval by the HEC [119], an autonomous agency set up in 2002. To obtain and maintain recognition (approval) by the HEC, institutions must have in place viable mission statements, adequate administrative and financial structures, facilities, academic programs, and faculty, and maintain internal quality assurance (QA) systems [120]. The assessment of institutions is mostly based on the evaluation of institutional self-assessments and HEC site inspections.

In addition, the HEC has established dedicated accreditation councils [121] responsible for quality assurance at the program level in specific disciplines (education, agriculture, computing, business, and technology). Independent accreditation councils also exist in professions like law, architecture, engineering, medicine, nursing, pharmacy, and veterinary medicine.

To promote a culture of continual quality improvement, the HEC introduced a ranking system [122] that rates HEIs on a scale from W (highest) to X, Y, and Z (lowest) based on criteria like QA mechanisms, teaching quality, or research output. However, while these rankings are designed to be an annual ongoing process, their results were last made available to the public in 2015. The top six institutions in the 2015 ranking were Quaid-e-Azam University (public), the University of the Punjab (public), the National University of Science and Technology (NUST, public), the University of Agriculture, Faisalabad (public), Aga Khan University (private), and the COMSATS Institute of Information Technology (public).

In recent years, the HEC has taken increased steps to enforce institutional compliance with QA regulations, amid scathing criticism of academic quality in Pakistan from education professionals and the public alike. In 2017, for instance, four institutions have been banned from admitting students [123] entirely, while another 13 had their distance learning MPhil and PhD programs suspended [124]. Current lists of recognized universities, campuses, authorized transnational providers and programs, as well as illegally operating institutions are available here [125].

International University Rankings

In comparison with academic institutions in other Asian countries, Pakistani universities are not very well-represented in standard international university rankings. While there are six Indian institutions included among the top 500 in the current 2020 Times Higher Education World University Rankings [126], for instance, Quaid-i-Azam University is the only Pakistani institution featured in this group (at position 401–500). Six Pakistani institutions are among the top 1,000, with COMSATS the highest ranked (601–800).

For the most part, Pakistan has a relatively consistent cluster of top institutions, most of them public, in terms of both domestic and international rankings. The four Pakistani HEIs among the top 1,000 in the current Shanghai Ranking [127] are COMSATS in the 501–600 band, and Quaid-i-Azam University, the University of Agriculture Faisalabad, and the University of the Punjab in the 801–990 band. The 2020 QS Rankings [128] feature the Pakistan Institute of Engineering and Applied Sciences (375), NUST (400), Quaid-i-Azam University (511–520), the Lahore University of Management Sciences (701–750), as well as COMSATS, the University of Engineering and Technology, and the University of the Punjab, all in the 801–1000 band.

THE HIGHER EDUCATION DEGREE STRUCTURE

Like other countries on the Indian subcontinent, Pakistan used to have bachelor’s degree programs that were only two or three years in length—a short duration by international standards. The traditional degree system was mostly structured into two-year bachelor’s programs (pass degree) followed by a two-year master’s degree (2+2), or more specialized three-year bachelor’s programs (honors degrees) followed by a one-year master’s degree (3+1).

However, the structure of higher education qualifications has undergone significant changes in recent years, transitioning to a four-year bachelor’s degree, followed by a one- to two-year master’s degree in line with global trends. Pakistan’s current national qualifications framework [129] spans eight levels, from elementary education to doctoral studies, emulating common academic qualifications frameworks worldwide.

It should be noted, however, that while most DAIs have moved to the new structure, vestiges of the old system still exist with some institutions still awarding the old 2+2 or 3+1 qualifications. Further complicating matters, academic institutions have developed a wide range of “bridging programs” to enable graduates from the traditional, short bachelor’s programs to enroll in graduate programs within the current system. Other changes include the introduction of a new two-year associate degree and the adoption of a U.S.-style semester and credit system. These changes not only replace the traditional system of annual examinations and mark sheets, they also facilitate the global recognition of Pakistani qualifications and international student exchange. Following are short profiles of the new credit system, the most common grading scale, and the primary benchmark credentials of the current system.

Grading Scale

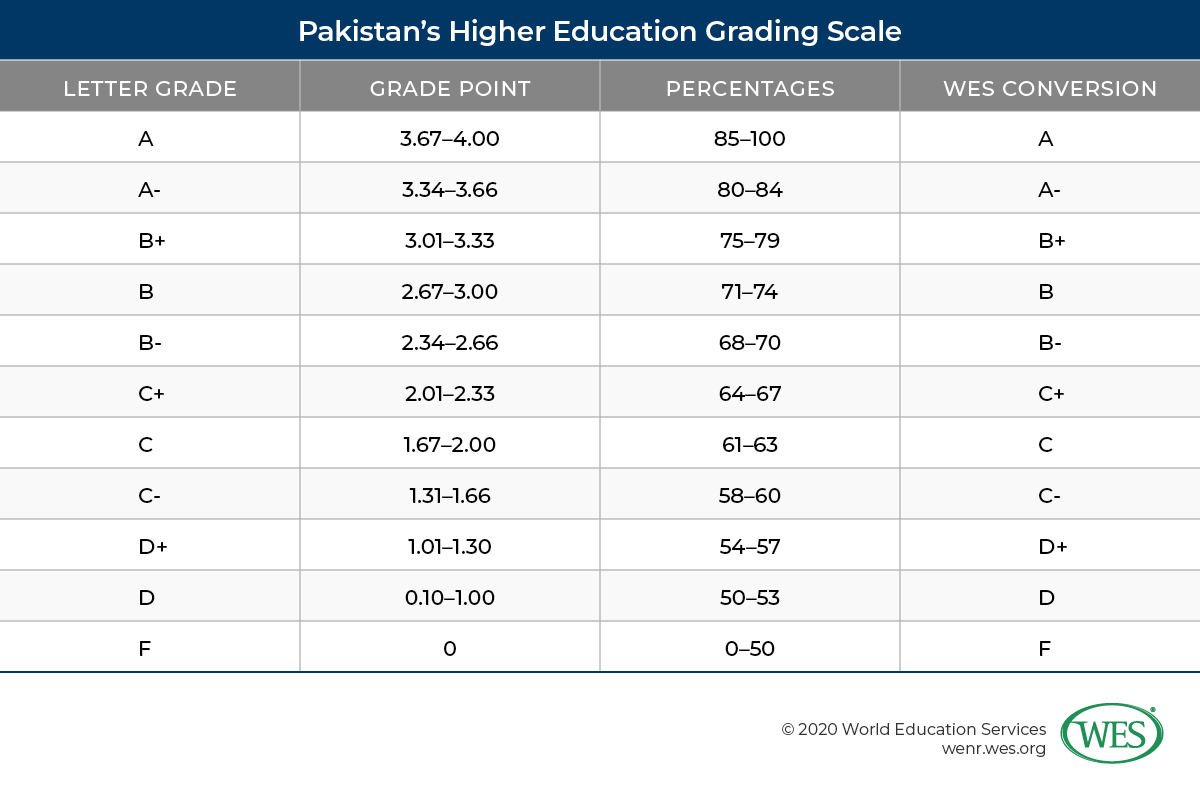

The HEC recommends the use of the following U.S.-style grading scale which has been adopted, with some variations, by a majority of HEIs in Pakistan. Note that academic transcripts may still indicate percentage marks, as used under the old system (see below), but the actual grade ranges are different. According to the official guidelines [66], a minimum GPA of 2.0 is required to graduate from bachelor’s programs, whereas a GPA of 2.5 or higher is required in the case of graduate programs.

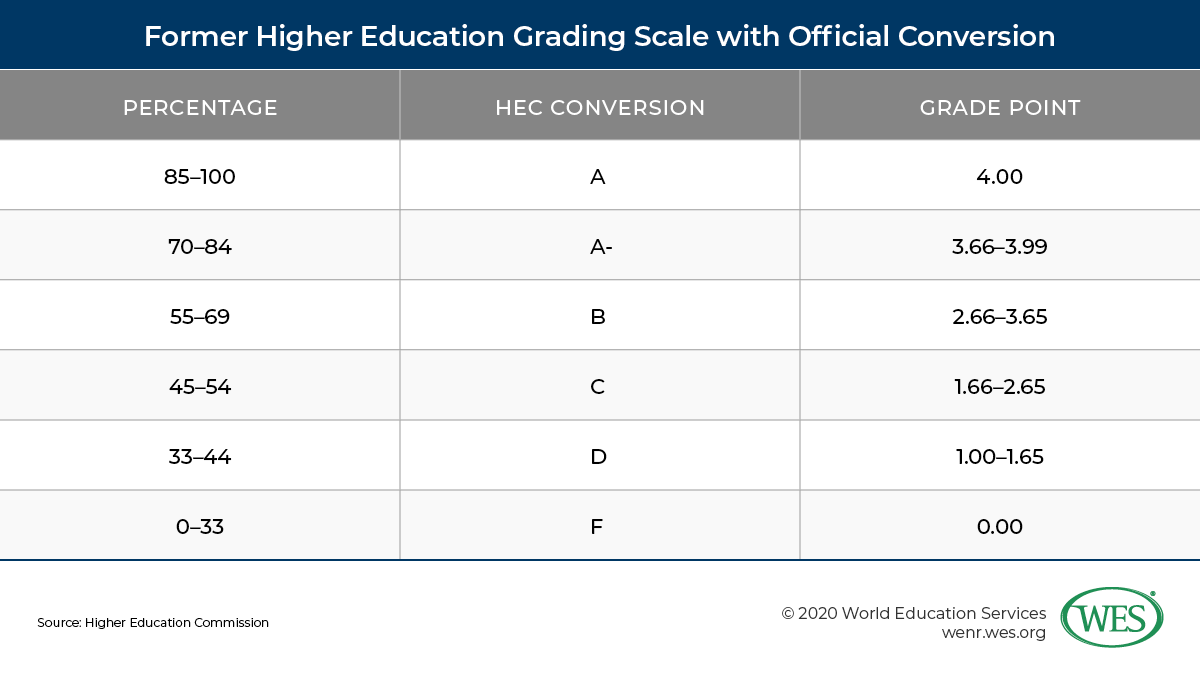

The previous grading scale was a percentage-based 0-100 scale akin to the secondary grading scale. For articulation between the different systems, the HEC recommends converting the old percentage grades to current letter grades as follows.

Credit System

The credit system stipulated by the HEC and used by most HEIs is a U.S.-style system. One credit hour [66] is equivalent to 50 minutes of classroom instruction each week throughout a semester of 16 to 18 weeks’ duration. A four-year bachelor’s degree requires the completion of 124 to 136 credit units, whereas a master’s degree typically requires 30 credits (either 30 credits of coursework or 24 credits of coursework and 6 credits of thesis, research, or project work [132]).

One credit hour of laboratory or practical work requires three contact hours per week throughout the semester. Credit hours are sometimes simply listed on academic transcripts without denoting whether the study was theoretical or practical. When theoretical and practical study are indicated, the corresponding credit hours are typically shown as two hyphenated digits within parentheses, for example, “4 (3-1).”

BENCHMARK CREDENTIALS

Associate Degree

| Admission Requirements | Higher Secondary School Certificate (HSSC); Intermediate Certificate; A Levels or other equivalent qualification |

| Duration / Credits | Two years / 60-72 credit hours |

| Fields of Study / Credentials Awarded | Awarded in primarily applied fields of study

Associate Degree in (field of study) |

| Gives Access To | Bachelor’s degree programs (with exemptions/transfer credit) in a related field of study |

| Additional Information | A relatively new credential; not frequently awarded today but expected to become increasingly common in the next few years.

Offered primarily in applied subject areas to train paraprofessionals to meet local labor needs, as well as a pathway to further study. |

Bachelor’s Degree

| Admission Requirements | Higher Secondary School Certificate (HSSC); Intermediate Certificate; A Levels or other equivalent qualification |

| Duration / Credits | Four years / 124–136 credit hours |

| Gives Access To | Master’s programs |

| Additional Information | Offered in many fields of study, most notably computer science, humanities, sciences and social sciences

Most common nomenclature used for name of credentials is Bachelor of (field of study)

|

Bachelor’s Degree (Professional Disciplines)

| Admission Requirements | Higher Secondary School Certificate (HSSC); Intermediate Certificate; A Levels or other equivalent qualification |

| Duration / Credits | Four years / 124–136 credit hours Five years / 160–170 credit hours |

| Gives Access To | Master’s degrees, advanced graduate level programs in professional disciplines

Professional practice |

| Additional Information | Four-year programs are offered in agriculture, education, engineering, or nursing*

Five-year programs are offered in architecture, dentistry, homeopathy, law, medicine, pharmacy, veterinary science, and traditional systems of medicine (Unani, Ayurveda, and homeopathic medicine)* * Reflects duration of majority of programs in that field of study. However, programs can vary in length. Programs in medical fields typically include a one-year internship or clinical rotation. |

Master’s Degree

| Admission Requirements | Bachelor’s degree (four years, 124–136 credits) or a combined 16 years of education. Dedicated Graduate Assessment Test (GAT) [133]for certain programs. |

| Duration / Credits | 1.5 to 2 years / 30 credit hours |

| Fields of Study / Credentials Awarded |

|

| Gives Access To | PhD programs |

| Additional Information | Programs may include a thesis or coursework only. |

Doctoral Degree (PhD)

| Admission Requirements | Master’s degree with a minimum GPA of 3.0, GAT depending on the program |

| Duration / Credits | Variable. At least 18 credits coursework followed by research and dissertation. |

| Additional Information | HEC-stipulated graduation requirements [134] include at least one scientific journal publication and the evaluation of the dissertation by two experts from academically advanced foreign countries [135] (in addition to local doctoral committee members). |

Note: In addition to these benchmark qualifications, universities offer a variety of shorter undergraduate-level diploma programs as well as postgraduate diplomas, which are mostly one year in duration and require a bachelor’s degree for admission. See, for example, the related program offerings [136] of the University of the Punjab.

Professional Education

Academic programs in professional disciplines like medicine, dentistry, pharmacy, and a few other fields are undergraduate programs of four- or five-years’ duration. Medical and dental programs are offered by dedicated medical and dental colleges. They lead to the award of the Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery degree and Bachelor of Dental Surgery, respectively. All colleges must be recognized by the Pakistan Medical Commission [137] (PMC) and must be affiliated with a degree-granting university. To practice, graduates must complete a mandatory one-year clinical internship and register with the PMC.

Certification in medical specialties requires another three to five years of clinical studies, depending on the specialty. In dentistry this requirement results in the award of the Master of Dental Surgery degree. In medicine, those completing a specialization are awarded the university degree of Doctor of Medicine and become members of the College of Physicians and Surgeons.

Indigenous medical systems like Unani, Ayurvedic, and Homeopathic medicine are licensed professions in Pakistan as well. In these fields, the Bachelor of Eastern Medicine and Surgery is awarded upon completion of a five-year program and one-year clinical internship recognized by the National Council for Tibb [138].

Admission into medical schools (Western or indigenous) and dental schools requires passing entrance examinations and a minimum aggregate score of 60 percent in both the SSC/Matriculation and the HSSC/Intermediate exams in the pre-medical group. Requirements also include an entry test. A fairly standard weighting of the selection criteria is 10 percent for the SSC, 40 percent for the HSC, and 50 percent for the entrance test.

Entry to the practice of law requires the completion of a five-year Bachelor of Laws (LLB) program, followed by a period of practical training and passing an examination conducted by one of Pakistan’s provincial Bar Councils. Study is conducted at law schools affiliated to a degree-granting university. Holders of a Master of Law (LLM) degree can practice and are exempt from the period of training and examination. LLM degree programs must be completed directly at degree-granting institutions and not at affiliated colleges.

Teacher Education

Pakistan has significantly tightened the academic requirements for school teachers in recent years. Until recently, elementary and middle school teachers (grades 1 to 8) were able to teach after completing short training programs that led to the Primary Teaching Certificate (SSC+1) and the Certificate in Teaching (HSSC+1). Today, Pakistan’s national regulations [139] formally stipulate a four-year bachelor’s degree in education or its equivalent as the minimum requirement to teach at Pakistani schools, from elementary through higher secondary levels. However, since teachers are hired at the provincial and regional levels, current practices vary significantly, predicated primarily on teacher shortages and a lack of qualified candidates.

The new associate degrees, awarded at affiliated colleges of education and community colleges, are being offered in education. In some provinces these new degrees have replaced the former Primary Teaching Certificate and Certificate in Teaching and now function as an interim credential. Those who have earned it are allowed to teach at the elementary school level while the system transitions to the new bachelor’s degree requirement. Postgraduate Bachelor of Education (BEd) credentials earned after one year of study following a two- or three-year bachelor’s degree in another discipline continue to be accepted for teaching positions at the lower secondary level (grades 9–10) as well.

WES Documentation Requirements

Secondary Education

- Final certificate (for example, Higher Secondary School Certificate or Intermediate Certificate)—sent by the applicable Board of Intermediate and Secondary Education

- Mark sheet/result card—sent by the applicable Board of Intermediate and Secondary Education

Technical and Vocational Education

- Diploma or Certificate (for example, Diploma of Associate Engineer or other diploma or certificate awarded by an applicable Board)

- Mark Sheet/Result Card sent by the applicable Board

Higher Education

- Photocopy of degree certificate—submitted by the applicant

- Transcript/Mark Sheet/Result Card—sent by the institution attended

- For completed doctoral programs, a written statement confirming the conferral of the degree—sent by the awarding institution

Sample Documents

Click here [140] for a PDF file of the academic documents referred to below

- Higher Secondary School Certificate (HSSC)

- Diploma of Associate Engineer (DAE)

- Bachelor’s Degree (university, four years)

- Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery

- Master of Arts

- Master of Philosophy

- Doctor of Philosophy

1. [141] When comparing international student numbers, it is important to note that numbers provided by different agencies and governments vary because of differences in data capture methodology, definitions of “international student,” and types of mobility captured (credit, degree, etc.). The data of the UNESCO Institute Statistics often provides the most reliable point of reference for comparison since it is compiled according to one standard method. It should be pointed out, however, that it only includes students enrolled in tertiary degree programs. It does not include students on shorter study abroad exchanges, or those enrolled at the secondary level or in short-term language training programs, for instance.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of World Education Services (WES).