Reforming a System in Crisis: How the Modi Government Is Revamping Medical Education in India

Stefan Trines, Research Editor, WENR

Fixing India’s broken health care system is a priority of the Indian government. In 2018, the administration of Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched, with much fanfare, a new public health insurance program (Ayushman Bharat), colloquially known as “Modicare.” The program is supposed to automatically cover hospitalization costs of up to 500,000 Indian rupees (USD$7,025) per year, per family for the poorest 40 percent of Indian society—some 500 million people—and establish 150,000 health and wellness centers throughout India by the end of 2020.

However, this highly ambitious project faces steep fiscal hurdles. Bringing it to full implementation will be difficult without simultaneously increasing the number of qualified health professionals and expanding and modernizing the country’s medical education system.

The Indian government is consequently pushing for extensive reforms in medical education. In August 2019, it succeeded in getting through parliament a major reform package, the National Medical Commission Bill, 2019—legislation Modi hailed as a milestone achievement to “curb avenues of corruption and boost transparency … accountability and quality in the governance of medical education.” He proclaimed that the reforms will “increase the number of medical seats and reduce the cost of medical education. This means more talented youth can take up medicine as a profession and this will help us increase the number of medical professionals.”

Indeed, the National Medical Commission (NMC) bill introduces substantial changes and is expected to have a major impact. It will replace the corruption-plagued Medical Council of India (MCI), the country’s regulatory body for medical education for the past eight decades, with a more centralized national commission. It will also revamp medical licensing procedures and enshrine several recent reform initiatives, such as the standardization of admission requirements at medical schools nationwide. To facilitate an understanding of these reforms, this article provides a brief overview of the current problems in Indian health care, as well as the structure of India’s medical education system, before analyzing in greater depth the system’s current changes.

What’s at Stake? Critical Shortcomings in Indian Health Care and Medical Education

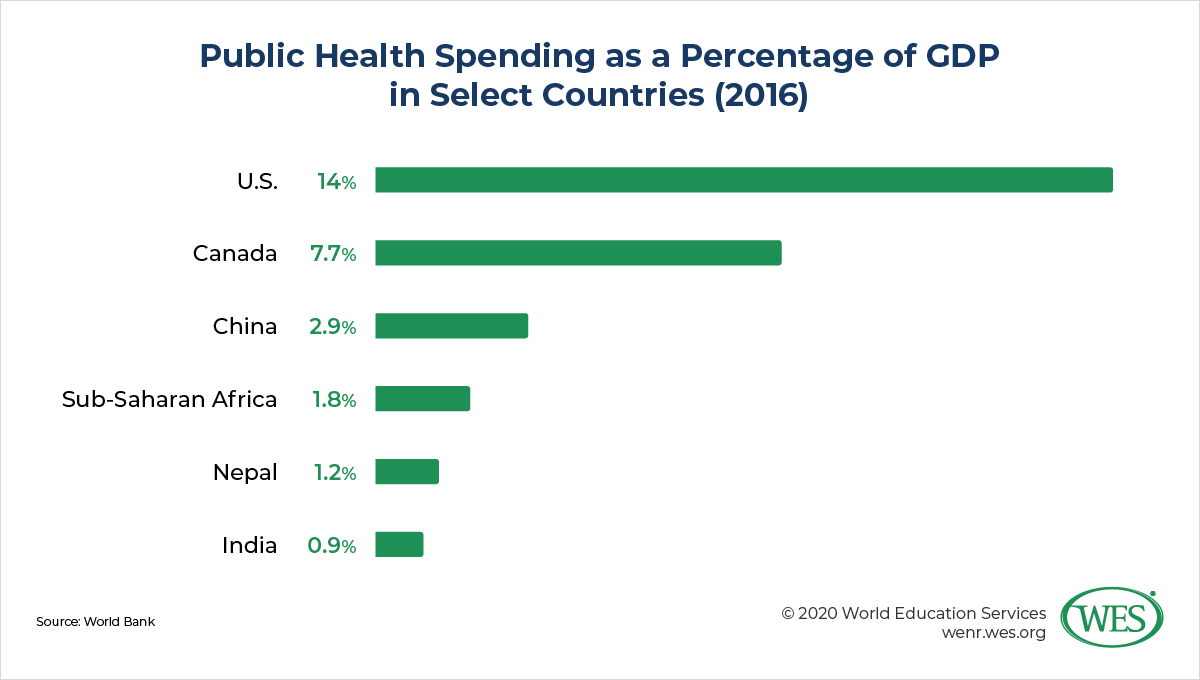

Despite enabling improvements in crucial health indicators like child mortality rates, India’s health care system fails to provide adequate medical services to large parts of the country’s growing population, especially in rural regions. Symptomatic of the crisis are India’s low levels of public health care spending, amounting to only 0.9 percent of GDP in 2016 (compared with an average of 1.9 percent in sub-Saharan Africa). While public hospitals offer free health services, these facilities are understaffed, poorly equipped, and located mainly in metropolitan areas. Most health services are therefore provided by private facilities, and 65 percent of medical expenditures in India are paid out of pocket by patients. Millions of families are consequently plunged into catastrophic debt or forced to forgo critical medical treatment altogether.

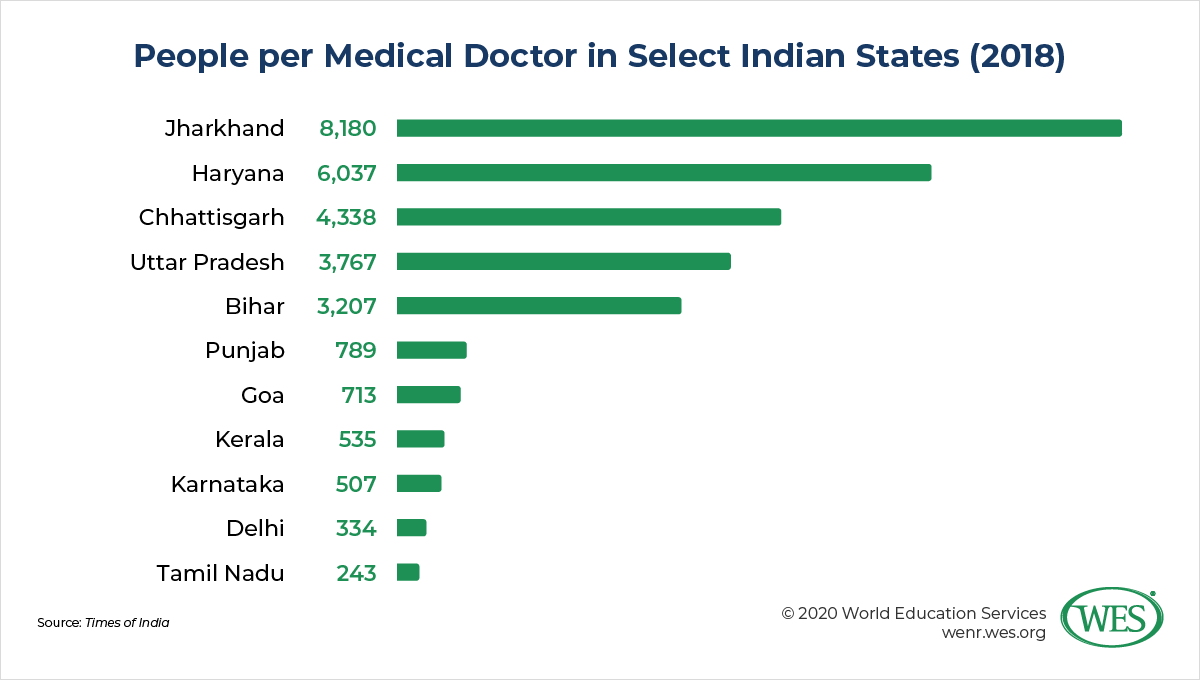

One of the most pressing problems is India’s severe shortage of medical doctors. According to the World Health Organization, the country has only 7.8 registered medical doctors per 10,000 people, compared with 18 doctors per 10,000 people in China, 21 in Colombia, and 32 in France. What’s more, not all registered doctors in India are actively practicing, and many are poorly trained. Consider that the majority of allopathic (science-based) practitioners in the country—57 percent—lack a formal medical qualification.

The situation is worse in rural regions, where 66 percent of India’s population lives. According to a recent study published in the British Medical Journal, there are only 1.8 and 1.9 physicians and surgeons, respectively, per 10,000 people in the underserved northern states of Assam and Himachal Pradesh—a ratio on par with African countries like Côte d’Ivoire. As Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Harsh Vardhan described it, most of India’s “rural and poor population is denied good quality care leaving them in the clutches of quacks.” What that means is that large parts of India’s population are served by unregulated informal practitioners who often use traditional, nonallopathic medicine and lack the medical training deemed necessary in developed societies.

While the country’s medical education system now produces more than 64,000 graduates in allopathic medicine a year, that number is vastly insufficient to keep up with demand. Shortages are further exacerbated by the outmigration of many of India’s most qualified doctors, a pattern that makes India the largest supplier of migrant physicians in the world. More than 10 percent of international medical graduates certified by the U.S. Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates, for instance, are Indian nationals. In the United Kingdom, likewise, Indian doctors are the largest group by far to have earned their medical qualifications overseas.

This brain drain is compounded by severe capacity shortages in India’s medical training system. Given India’s needs, the country’s medical schools have grossly inadequate numbers of seats and dismal admission rates. Consider that no less than 338,000 students competed over 1,150 open MBBS slots in the 2019 admissions test for the prestigious public All India Medical Institutes of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), so that a mere 0.34 percent of candidates were admitted. Admission into private schools—which enroll about half of India’s medical students—is easier, but these institutions charge exorbitant fees and are unaffordable to all but students from affluent households.

Admissions bottlenecks and the high costs of medical study in India not only provide a breeding ground for corrupt practices in admissions or examinations, they also drive some 5,000 Indians abroad each year to study medicine in countries like China, Russia, Ukraine, and even Bangladesh. The best-educated of these students often don’t return home after graduation because they can find better-paying employment opportunities in Western countries or the Persian Gulf region. Those who return tend to face difficulties in registering to practice medicine in India: Only 26 percent of internationally trained doctors passed the mandatory Foreign Medical Graduates Examination in 2018.

A Brief Overview of India’s Medical Education System

The standard entry-to-practice degree in modern medicine in India is the Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS), a credential earned upon completion of a five-and-a-half-year undergraduate program. The curriculum is divided into one year of preclinical studies in general science subjects and three and a half years of paraclinical and clinical studies, followed by a one-year clinical internship. Before beginning the internship, students are required to pass several examinations, the final one of which is conducted in two parts. Graduate education in medical specialties typically takes three additional years of study after the MBBS and concludes with the award of the Master of Surgery or Doctor of Medicine. Postgraduate diplomas in medical specializations may also be awarded upon the completion of two-year training programs.

Of note, India has various ancient systems of medicine that long predate the introduction of modern Western medicine during British colonial rule. Traditional systems like Ayurveda, Yoga, Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha, and Homeopathy (collectively referred to as AYUSH) are common forms of medical care in India, especially in rural regions. While these forms of medicine play only a limited role in India’s public health care system and are often practiced informally, practitioners are officially mandated to be licensed by one of the country’s 29 state medical councils, just as doctors of modern medicine are. Professional degree programs in traditional systems are structured similarly: Credentials like the Bachelor of Ayurvedic Medicine and Surgery or the Bachelor of Homeopathic Medicine and Surgery are awarded upon the completion of five-and-a-half-year undergraduate programs. Graduation typically requires passing annual examinations and completing a final one-year internship. In terms of oversight, AYUSH education is, with some exceptions, regulated by a separate ministry and does not fall under the purview of the MCI or the new National Medical Commission.

Expansion of the System: Rapid Growth of the Number of Medical Schools

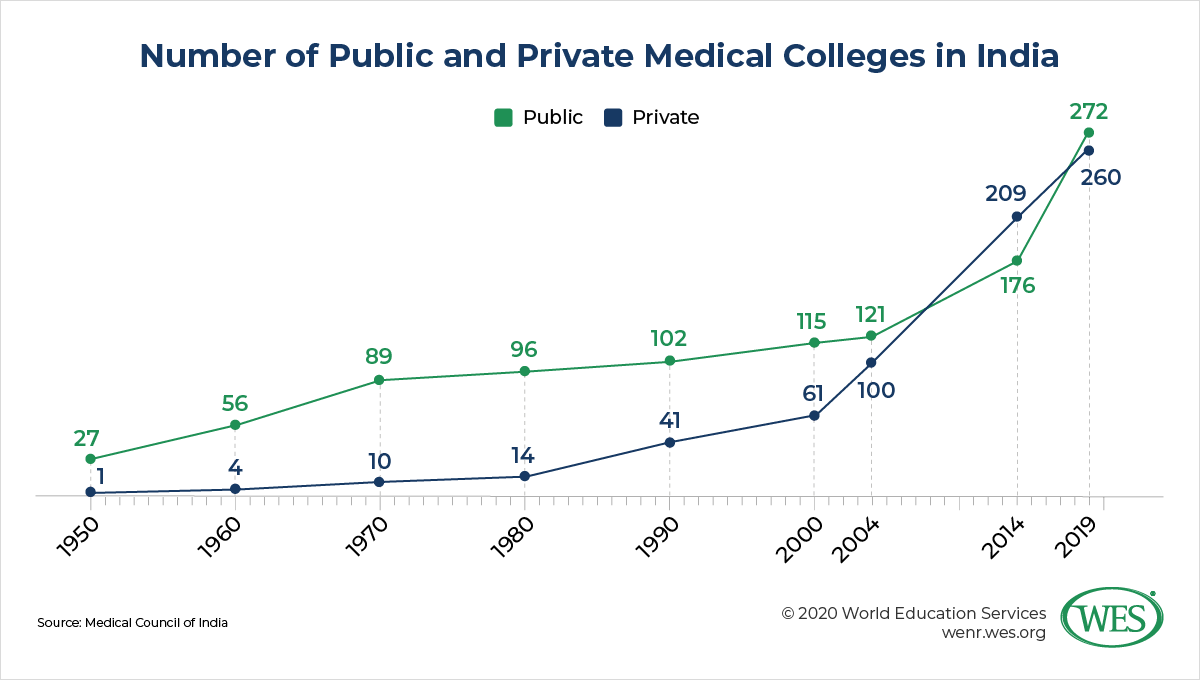

India’s shortage of medical doctors belies the fact that the number of medical schools in the country has skyrocketed over the past few decades, resulting in India now having more of these institutions than any other country in the world next to China. Between 1950 and 2014, the number of medical colleges in India surged from 28 to 384. Today, there are 532 medical schools approved to offer MBBS programs, predominantly concentrated in the south of the country. Except for autonomous institutions like AIIMS, these schools don’t have degree-granting authority and are affiliated to universities, such as the NTR University of Health Sciences or the Tamil Nadu Dr.M.G.R. Medical University, to name but two examples. These universities administer exams and award the final degrees. The intake of medical schools generally ranges from 100 to 250 new students a year.

India’s medical education system expanded rapidly after India liberalized its largely state-run economy in the early 1990s and came to view private medical education as a means of expanding capacity amid fiscal constraints. More than 80 percent of private medical colleges in India were set up after 1990, most of them in socioeconomically more advantaged states like Karnataka, Kerala, and Puducherry.

This mushrooming of private providers has overburdened regulatory authorities and created quality problems, leading to a disparate medical education system. Some private institutions, such as the Christian Medical College, Vellore, one of India’s oldest private medical colleges, and St. John’s Medical College, another long-standing philanthropic provider, are among India’s top medical schools. On the other hand, many of the newer private institutions are of substandard quality. While they have helped expand capacity, many of them “are funded by businessmen and politicians with no previous experience of running medical schools.”1 These institutions are marred by shortages “of faculty, laboratory facilities, and patient load that have led to poor quality education and the production of [an] unskilled health workforce.” According to the Times of India, some colleges are operating “with little or no facilities, no patients and fake faculty.”

Many private institutions are said to take in enormous amounts of money by selling scarce college seats on the black market for capitation fees or “donations,” a practice that facilitates the admission of well-heeled but academically unqualified students. To curb these corrupt practices, Indian authorities in 2016 dropped legal provisions that barred medical colleges from operating as for-profit institutions in an attempt to allow them to make profits that are more transparent—and subject to taxation. But this development has led to private colleges raising their already exorbitant admission fees even higher.

As outlined below, current reforms seek to rectify these problems with standardized admissions procedures and partial caps on tuition fees. Beyond that, the Indian government has substantially increased the number of public medical colleges. After approving the establishment of 82 new public medical schools in 2017 and 2018, the government in 2019 greenlighted the creation of 75 additional colleges in underserved areas. The number of AIIMS branches, for instance, is slated to increase by 22 facilities to reduce regional imbalances in access to medical education across the country. It should be noted, though, that several AIIMS branches that were established in 2012 are still not fully operational because of instructor shortages and a lack of equipment. Overall, the goal is to increase the number of seats in MBBS programs nationwide from 79,500 in 2019 to nearly 100,000 within the next five years and to “ensure that there is at least one medical college between every 3 districts” out of a total of around 700 districts in India.

Standardization of Admissions Procedures

Until recently, admission into MBBS programs was based on different entrance exams conducted by states or individual colleges, as well as the All India Pre Medical Test (AIPMT) administered by the Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE), a national body managed by the union government. To centralize this system and standardize admissions procedures nationwide, the federal government in 2012 introduced the National Eligibility Cum Entrance Test (NEET) for admission into all medical and dental programs in India.

Several state governments viewed the national test as an infringement on the rights of states, and a supreme court ruling declared the universal implementation of the NEET unconstitutional between 2013 and 2016. However, the court recently reversed course, and the NEET is now designated the sole admissions criterion for medical programs in the 2019 NMC bill. Despite continued resistance in some states, all medical schools, including private institutions, must now use the test, which since 2018 has been administered by the autonomous National Testing Agency. Two autonomous public schools that are designated as “institutes of national importance”—the Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research and AIIMS—currently still conduct their own entrance examinations, but these institutions are expected to soon start using the NEET as well. India’s Supreme Court in 2019 also upheld that the NEET is mandatory for admission into AYUSH programs.

To qualify to sit for the NEET, candidates must have sufficiently high grades in their upper-secondary school-leaving examinations and must have sat for exams in physics, chemistry, and biology (or biotechnology), as well as English. The NEET is a three-hour multiple-choice test in physics, chemistry, and biology held annually at more than 2,000 testing centers across the country (it may be given twice a year in the future). Pass rates vary considerably by jurisdiction; in 2019 they ranged from 75 percent in Delhi to 35 percent in Nagaland. Candidates who pass the NEET then undergo further selection by the central government (15 percent of seats nationwide under an All India Quota) and state governments (85 percent of seats) before they are allocated to schools based on their NEET scores.

Private schools generally require lower scores for admission. In Punjab, for instance, the student with the highest NEET score who was admitted to a private college “had lower marks than the last student admitted to the open category in each of the government colleges.” Minimum score requirements for disadvantaged social groups (scheduled castes and tribes and “other backward classes”) are also lower, and there are special quotas of reserved seats for students from these groups.

The nationwide NEET has several advantages over the old decentralized system. It limits the scope for corruption at individual institutions and lessens the burden on applicants, since they no longer have to sit for different entrance exams in different states and institutions. On the downside, applicants now have only one shot at passing a single high-stakes exam, whereas they previously had several pathways to admission in various jurisdictions and schools. The change was most drastic for the state of Tamil Nadu, where applicants were previously admitted based solely on their upper-secondary school exams and did not have to sit for entrance tests at all.

Opposition from state governments also stems from the fact that the NEET is patterned after the AIPMT and based on the CBSE higher secondary school syllabus. As a result, some states argue, students examined by state boards are at a disadvantage. Secondary education boards in the states will now have to tailor their syllabi to accommodate the NEET. However, the adoption of the NEET will ultimately curb subpar admission practices by ensuring that all applicants are admitted based on uniform standards nationwide.

Regulation of Tuition Fees

Until recently, the regulation of fees at private medical schools was largely the prerogative of India’s states, and deemed-to-be universities were mostly exempted from regulation altogether. Most states have passed fee-related legislation or set up so-called fee fixation committees or fee regulating authorities. The NMC bill, by contrast, introduces greater centralization. It gives India’s new medical commission the power to regulate tuition and other fees for 50 percent of seats at private medical schools and deemed-to-be universities. State governments will still decide fees for the remaining seats based on memorandums of understanding with private colleges.

The government plans to drastically cut fees for the seats under its control and argues that fees for the remaining seats will be kept within limits by market forces— likely an unrealistic expectation, given the extreme scarcity of medical seats in India. The decision to limit government control to 50 percent of seats has consequently been severely criticized by stakeholders, including state governments and the Indian Medical Association. It appears that the union government’s intention is to keep private medical colleges profitable so as not to stymie their growth, which the government continues to view as essential for expanding capacity.

While no concrete steps have been taken so far regarding the seats under government control, current proposals suggest slashing tuition by up to 90 percent for postgraduate seats—which are even more scarce and expensive than MBBS slots. MBBS fees, meanwhile, are expected to be capped at anywhere between USD$8,000 and USD$14,000 per annum, compared with a current average of USD$35,000 in jurisdictions like Delhi and Maharashtra. Critics fear, however, that the new provisions will “encourage ‘under the table’ capitation fees and other periodic fees on various pretexts.”

Changes in Regulatory Structures and the Oversight of Medical Schools

The Medical Council of India (MCI) has been the country’s regulatory body for medical education and licensing since 1934. Made up of elected representatives from medical universities, medical practitioners, and members nominated by state governments and the union government, the MCI was responsible for making recommendations on authorizing the establishment of new medical colleges, the withdrawal of said authorizations, annual inspections and the periodic licensing of institutions; setting admissions quotas and quality standards in medical education, and codes of ethics for medical doctors; and maintaining a national registry of doctors.2

In recent years, the MCI has come under increased scrutiny and been accused of corruption, “inefficiency, arbitrariness and lack of transparency,” a state of affairs abetted by the fact that many of its council members held office for lengthy periods of time by being re-elected or re-appointed in different positions within the council. A scathing parliamentary commission report from 2016 lambasted the MCI for “deep systemic malice,” the “failure to maintain uniform standards of medical education,” and for being subservient to unethical corporate interests “against larger public health goals and public interest.” It recommended that MCI college inspections “be [scrapped] and an autonomous accreditation body [be established] … to assess and accredit institutions of higher education … in the domain of medical education to deal with issues of quality.” (Medical colleges can seek voluntary accreditation by the National Assessment and Accreditation Council (NAAC), but there’s no accrediting body dedicated to medical education, and only a few medical colleges hold NAAC accreditation.)

There is little question that corruption was rife in the approval of medical colleges and enrollment quotas. In 2010, for instance, MCI President Ketan Desai was arrested for soliciting a bribe of 20 million rupees (about USD$450,000 at the time) for allowing a private medical college in Punjab to enroll students despite the MCI having found the college’s infrastructure inadequate. Reports also surfaced of private medical colleges being warned about surprise inspections, so that they could pass them with the help of ghost faculty and patient impostors. According to a Reuters investigation, “recruiting companies routinely provide medical colleges with doctors to pose as full-time faculty members to pass government inspections. To demonstrate that teaching hospitals have enough patients to provide students with clinical experience, colleges round up healthy people to pretend they are sick.”

After years of neglecting to rein in such abuses, the union government in 2018 placed the MCI under the oversight of an appointed Board of Governors ahead of replacing it with the new National Medical Commission (NMC) in 2020. The NMC will be under greater central government control; unlike the MCI, it will have only very few elected members. It will be overseen by appointed members under a chairperson selected by the central government—a medical professional who has at least 20 years of experience—as well as rotating part-time members representing the state governments. In addition, there’s a Medical Advisory Council in which India’s state governments “may put forth their views and concerns before the Commission and help in shaping the overall agenda, policy and action relating to medical education and training.” AIIMS Professor Suresh Chandra Sharma, chief of the head-neck surgery department, was recently chosen as the first NMC chair. The other members of the council were announced in October 2019. They include vice chancellors of medical universities and representatives from state medical councils. To avoid the revolving-door patronage system that plagued the MCI, NMC members have term limits of two to four years.

Under the council, there are four autonomous boards tasked with regulating different areas:

- The Under-Graduate Medical Education Board and the Post-Graduate Medical Education Board set standards of medical education and curricula at their respective levels, as well as minimum standards for medical institutions and faculty training.

- Based on these standards, the Medical Assessment and Rating Board grants permission for the establishment of new medical institutions, the initiation of postgraduate programs, or increases in enrollments. It is authorized to “carry out inspections of medical institutions for assessing and rating such institutions.” If deemed necessary, the board may task a third-party agency with the inspection and assessment of medical institutions. It can issue warnings, impose monetary penalties, reduce admission quotas, or recommend the withdrawal of institutions’ recognition based on factors like inadequate facilities, faculty, or fiscal resources.

- Finally, the Ethics and Medical Registration Board is tasked with maintaining a digital national register of licensed medical practitioners based on the medical registers of India’s states. It sets standards for professional conduct and medical ethics, and enacts these standards in coordination with the medical councils of the states.

New Licensing Requirements: The National Exit Test

The NMC bill introduces for the first time a nationwide licensing exam for medical doctors in India—the National Exit Test (NEXT) devised by the NMC. Administered at the end of the final year of the MBBS program, the test will be required to obtain a license to practice and become registered as a medical professional in state and national registers. The NEXT will come into effect three years after the enactment of the NMC bill. It will be a universal requirement for all physicians, including foreign-educated medical graduates, who currently sit for a separate test, the Foreign Medical Graduates Examination. Doctors who practice without being registered are subject to punishment of up to one year of jail time. Passing the NEXT will also be a requirement for admission into postgraduate programs in medical specialties, replacing other entrance examinations currently in place.

The government expects that the uniform graduation examination will over time ensure a consistent quality of medical education nationwide. Health Minister Vardhan has explained that the NEXT will ensure that the new NMC “moves away from a system of repeated inspections of [institutions and] infrastructure and focuses on outcomes rather than processes.” Addressing concerns that the NEXT might make it more difficult to obtain licensure and thereby exacerbate the shortage of physicians in India, he clarified that there will be no limits to the number of times medical graduates can retake the NEXT exam.

New Medical Curriculum

In 2019, the MCI rolled out a new competency-based medical curriculum to align medical education more closely with the “changing health needs of the country” and promote a more patient-centered approach. While the curriculum stresses the acquisition of global medical competencies, it also seeks to produce graduates who are able to effectively provide medical services to India’s local communities. Changes include the introduction of a foundation module to impart basic language, communication, and computer skills, as well as a more extensive AETCOM (attitude, ethics, and communication) module to prepare students to communicate with patients. The curriculum is more integrated across different medical subjects and provides clinical exposure earlier than before—during the first year of the MBBS program. The summative assessment of students in year-end examinations has been augmented with a more consistent and continual assessment of core competencies.

Community Health Providers

One of the most controversial elements of the NMC bill is a provision that allows the medical commission to grant limited licenses to “mid-level practitioners” without full-fledged medical degrees to provide primary and preventive health care services in underserved areas. India’s health ministry has argued that “it will take 7-8 years to ramp up the supply of doctors, therefore, in the interim we have no option but to rely upon a cadre of specially trained mid-level providers who can lead” the new health and wellness centers that the Modi administration is establishing in rural areas.

While the bill does not include concrete eligibility criteria for mid-level community health providers, it’s likely that the criteria will resemble those in already in place Assam, where a severe shortage of physicians caused the state government in the mid-2000s to start a Diploma in Medicine and Rural Health course to train community health providers. An upper-secondary school diploma is required for admission to the three-year course, the first year of which focuses on preclinical studies; the second, paraclinical studies; and the third, clinical studies based on the MBBS curriculum, including a six-month internship at a hospital. Attempts by the union government to launch a similar Bachelor of Science in Public Health program faltered a few years back but may now be revived. Several bachelor programs for physician assistants already exist, but are offered mostly by private institutions and lack broader public acceptance and formal licensing procedures.

Postgraduate training programs for community health providers are another option. Initially, the NMC bill included a provision for a two-year bridge course for AYUSH doctors, completion of which would have allowed practitioners of traditional medical systems to prescribe allopathic medicines. However, the medical establishment’s resistance to this proposal was so fierce that the government eventually dropped it and left to state governments to decide, based on local needs, whether to implement AYUSH bridge courses. Given the shortage of allopathic physicians in India, AYUSH medicine has become increasingly “mainstreamed” in recent years. AYUSH doctors are already posted with some frequency to primary health care centers in an adjunct role, predominantly in rural regions. Several states allow AYUSH doctors to prescribe allopathic medicines in emergencies. The state of Maharashtra in 2019 introduced a six-month bridge course for Ayurveda doctors that allows them to work as mid-level health providers in health and wellness centers.

Despite the removal of the AYUSH bridge course from the NMC bill, the union government is now authorized to issue up to a third of licenses in the national register to community health providers. To the dismay of critics, these mid-level practitioners can independently prescribe select medications in primary and preventive health care. The Indian Medical Association (IMA) derided the bill for allegedly “opening the floodgates” for the licensing of 350,000 “legalized quacks”: “Why should we follow Sub-Saharan states in the concept of Community Health Worker Providers or China in producing barefoot hybrid doctors?3 … Providing license to practice and prescribe to a non-medical quack is in effect a license to kill.”

A Step in the Right Direction Despite Flaws

The IMA’s scathing criticisms are but one example of the vested interests vehemently opposing the current reforms. For one, critics fear that the NMC will create an overly centralized, bureaucratic system that reduces the role of India’s states. Given the inadequacies of the previous system and the fact that India has one of the most corrupt health care and medical education systems in the world, however, it’s hard to see how a more centralized system and more uniform, outcome-based quality standards can be much worse. On paper at least, the current reforms are sensible measures aimed at improving a poorly functioning system, even though they may stifle innovation at individual institutions. Standardizing admission requirements and licensing procedures across India is a step in the right direction. These measures are bound to help create a medical education system of more consistent quality and contain the proliferation of substandard schools.

That said, much will depend on how the reforms are implemented and how effective Indian authorities are in stamping out corruption. A regulatory commission made up of rotating, nominated members does not necessarily “guarantee excellence. In fact, quite the reverse may happen when with a number of time servers being nominated, the chief qualification being proximity to the government of the day. Regulatory capture by private colleges which are ready and able to pay bribes will continue to be a threat.” On the upside, the fact that core functions of the NMC have been delegated to three autonomous boards is a significant improvement that should provide greater checks and balances. Unlike under the MCI, quality standards will be set and implemented by different bodies.

Capping the skyrocketing tuition fees for 50 percent of private medical seats is a commendable measure, but it only goes halfway. The cash-strapped Indian government continues to rely on private providers to alleviate capacity gaps in medical education and leaves the regulation of fees for half of all private seats to the states. While advocates of private medical education argue that private colleges should be able to set their own tuition fees to allow for the development of well-funded, high-quality private institutions, there’s a risk that predatory practices will continue to fester in some states.

Critics deride the health care reforms for emphasizing quantity over quality and warn of the dangers of allowing community health providers who lack medical degrees to deliver primary health care services, even under the supervision of physicians. Given the weak regulatory structures in India, such concerns have some merit, but they ignore the fact that the deployment of health workers without full-fledged medical training is common in other countries and can make a crucial difference in improving health care. In the United States, the physician assistant (PA) profession was created for the very same reasons that drive current reforms in India—to address the shortage of physicians and expand health services, particularly in rural regions.4 The PA model has become an accepted and growing practice globally. The U.K., for instance, is currently expanding the training of “physician associates” to improve primary care in underserved regions. China, likewise, utilizes community health care centers as a key component of its health care strategy to great effect. Paraprofessional village doctors, dubbed “barefoot doctors,” have helped to greatly reduce child mortality rates and increase life expectancy in the country in past decades.

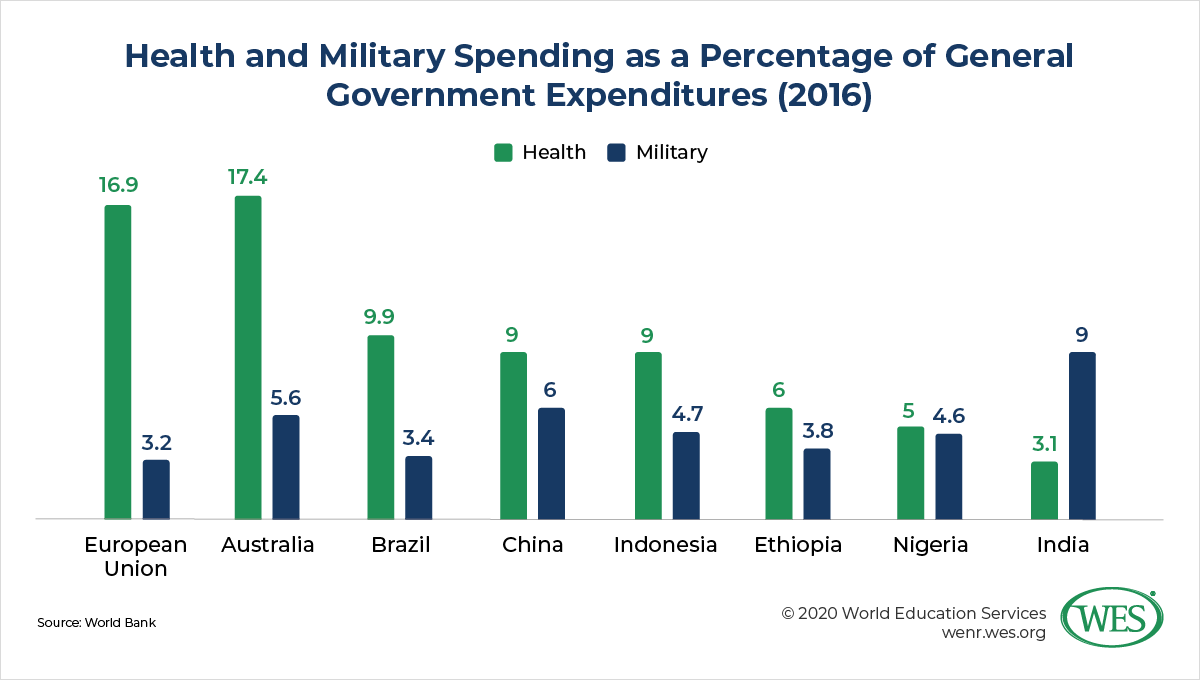

Relying on mid-level practitioners who’ve had only basic medical training may not be a perfect solution, but if India can establish and enforce a strong regulatory system for community health practitioners, these workers could make critical contributions to primary care. Further improvements in medical services in rural areas could be achieved if a compulsory rural service period for MBBS graduates would be introduced—a policy recently enacted by India’s Supreme Court that is already practiced in several states but thus far isn’t compulsory nationwide. Perhaps most crucially, all of India’s reform efforts continue to be constrained by abysmally low government spending on public health care. Despite the festering crisis of its health care system, India spends three times more on defense than on health care. It remains to be seen if the Modi administration will reverse these priorities in the years ahead.

1. Supe, Avinash and Sahoo, Soumendra: Malpractice in Medical Education. In: Nundy, Samiran; Desiraju, Keshav; Nagral, Sanjay (eds.): Healers or Predators: Health Care Corruption in India, Oxford University Press, 2018, Kindle edition, locations 2345-2487:2386.

2. For a more detailed overview of the history and functions of the MCI, see: Pandya, Sunil K: The Role of the Medical Council of India, in Supe et.al., op..cit., locations 2048 – 2328.

3. “Barefoot doctors” is a common colloquial term for village health care providers in China that provided medical services after undergoing basic, short-term medical training. Beginning in the 1960s, these practitioners were deployed in great numbers to provide primary health care in China’s countryside.

4. The return and integration of medical corpsmen from the Vietnam War was another factor that contributed to the growth of the physician assistant (PA) profession in the 1970s. “Other PA prototypes included the assistant medical officer in Micronesia, Fiji, and Papua, New Guinea; the apothecary in Ceylon; the public health worker in Ethiopia; the clinical assistant in Kenya; the barefoot doctor in China; the practicante in Puerto Rico; the rural nurse in Cuba; the officier de santé in France; and the feldsher in Eastern Europe.” (Dehn et al: Research on the Physician Assistant profession: The medical model shifts, in: The PA Profession: 50 Years and Counting, published by the Journal of the American Academy of Physician Assistants and the Journal of Physician Assistant Education, pp. 15–21).

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of World Education Services (WES).