Sidiqa AllahMorad, Knowledge Analysis Manager, WES, Chris Mackie, Editor, WENR

Kazakhstan is a country in transition. Since 1991, when it became the last of the former Soviet republics to declare independence, its leaders have sought to transform the country’s economy, release it from the grip of central planners, and open it to market forces. Kazakhstan’s leaders have also sought to similar transformations elsewhere, at least nominally. Government officials have proclaimed a desire to decentralize political power, to reverse decades of international isolation, and to unify an independent, autonomous nation that for more than half a century had been tightly integrated into the Soviet Union.

But, as the length of that still-incomplete transition suggests, their success has been mixed. At times, continuity has held the upper hand over change, and lasting imprints of the country’s Soviet past still mark the land and its people. Despite ambitious restoration efforts [2], the Aral Sea [3], once the world’s fourth-largest lake, has shrunk to a 10th of its previous size after decades of Soviet riverine diversions for irrigation and hydropower projects. Russian, the language of politics, commerce, and education in the Soviet Union, also remains the most widely spoken language in Kazakhstan, although reform efforts aimed at promoting the Kazakh language have achieved considerable success.

This transition has not spared Kazakhstan’s education system. Since independence, the government has embraced educational reforms aimed at opening education provision to the free market, decentralizing administrative oversight and accountability, integrating the education system more closely with the international community, and leveraging education to unify the nation. In recent years, given the country’s economic and political ambitions, the rush to transform the education system has only intensified.

But, as in other sectors, progress has been far from steady. In a syncopated series of advances and retreats, government officials have announced ambitious reforms, only to quickly walk them back. The basis for these reforms, as well as that of so much else in contemporary Kazakhstan, can ultimately be found in the turmoil of the country’s immediate post-independence social, political, and economic experience.

Post-Independence: A Decade of Change and Continuity

The dissolution of the Soviet Union sent shockwaves through every corner of Kazakhstani society, triggering outbreaks of long-forgotten diseases [5], fears of violent political unrest, and a mass exodus of ethnic minorities. The country’s economy was hit particularly hard. A constituent republic of the Soviet Union since 1920, the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic (Kazakh SSR), as it was known from 1936 to 1991, was of all the former Soviet republics one of the most closely tied to the metropole [6]. Its economy had long depended on the seamless transportation of natural resources pulled from its rich soils and taken to other Soviet republics for processing.

As these now post-Soviet states introduced new tariffs and customs, disrupting the country’s long-established supply chains, Kazakhstan’s economy crashed. Between 1990 and 1995 the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) fell by 31 percent [7].1 [8] Hyperinflation ran rampant, reaching nearly 3,000 percent [9] in 1992, as the government lifted price controls and expanded the money supply to cover large budget deficits. Growth remained sluggish until 1999, hindered as it was by low oil prices and a severe economic decline in Russia, still Kazakhstan’s largest trading partner [10], culminating in the 1998 Russian financial crisis.

The dissolution also caused immense social dislocation. Over 1.7 million ethnic Russians [11] and more than half a million, or nearly two-thirds, of ethnic Germans left the country between 1989 and 1999. At the same time, the birthrate [12] of those remaining plummeted, causing the size of the population to contract by more than 9 percent [13] between 1991 and 2001, when it reached 14.9 million. These losses compounded the country’s economic troubles. The loss of large numbers of Russians and Germans, a disproportionate number of whom had previously held skilled positions in the Kazakh SSR’s government and largest industries, left a gaping hole in the country’s labor supply.

These early social and economic troubles were influential in shaping the earliest phase of the nation’s independence. Combined with a loss of subsidies from Moscow and disruptions to tax collection mechanisms, the faltering economy sharply reduced government revenue, leading to a rapid deterioration in the quality of public services. The collapse also forced the government to consider drastic economic reforms, which it laid out explicitly in the Kazakhstan 2030 Strategy [14]. Adopted in 1997, this strategy prioritized reducing government interference in domestic and foreign trade, improving tax and tariff administration, revising corporate governance structures, encouraging foreign investment and international ties, and privatizing state-owned enterprises.

The push to privatize public enterprises had a particularly consequential impact on the future of the country and its education system. In the 1990s, it prompted a fire sale of state assets. Foreign investors, hoping to capitalize on bargain prices for a stake in Kazakhstan’s rich oil fields, descended on the country. By 1999, nearly half of all medium-size and two-thirds of all large state enterprises had been sold off, according to the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development’s [15] (EBRD’s) 1999 Transition Report [16].

Although nowhere near as thorough as it was in other sectors of the economy, this privatization drive extended to education as well. The 1990s witnessed a rapid expansion of private academic institutions, many of which, as time proved, were of very poor quality. Although most public schools and universities remained under tight government control, legislation issued shortly after independence introduced tuition fees at public universities.

While international financial institutions praised Kazakhstan’s leaders for their enthusiastic embrace of privatization, other observers were more skeptical. In 1999, Transparency International ranked Kazakhstan in the bottom quintile of its Corruption Perceptions Index [17]. In the years that followed, news reports exposed the dark underbelly of Kazakhstan’s free market reforms, revealing a world of backroom deals and widespread kickbacks extending to the highest levels of government. In 2003, two businessmen from the United States [18], one a former Mobil Oil Corporation executive, were charged in connection with $78 million in bribes to secure oil contracts. The bribes were paid to two high-level Kazakhstani officials [19]: the former prime minister, Nurlan Balgimbaev, and Kazakhstan’s president, Nursultan Nazarbayev.

While Kazakhstan’s post-independence economic transformation was rapid and disruptive, its political system was characterized by far more continuity. Nazarbayev, who had for years served as the prime minister of the Kazakh SSR and chairman of its Communist Party, transitioned smoothly into the newly independent country’s top post as president. Although ostensibly running the country as a democracy, once in power Nazarbayev quickly cracked down on any political opposition, winning multiple elections with more than 95 percent of the vote. Surprisingly, international election monitors have criticized every election [20] since [21] independence as unfree and coerced. Nazarbayev also quickly moved to centralize power in the Office of the President, keeping a tight grip on all levels of government. It remains to be seen what impact Nazarbayev’s resignation in 2019 [22] will have on democratic processes. Despite resigning, Nazarbayev remains the chairman of the country’s most powerful military institution and the leader of its dominant political party.

These events had a formative influence on the course of Kazakhstan’s later history, and on its education system in particular. Although conditions in the new millennium changed dramatically, the turmoil of these early years continue to shape the country to this day.

The New Millennium: Kazakhstan’s Uncertain Future

Kazakhstan’s experience in the twenty-first century differs markedly from that of the last decade of the twentieth. In 1999, Kazakhstan’s economy entered a new phase of rapid expansion, spurred by the devaluation of the tenge [23], Kazakhstan’s currency, and the start of a nearly decadelong period in which the global price of crude oil [24] increased more than 10-fold. In 2006, after more than half a decade during which annual GDP growth rates [25] hovered at around 10 percent, Kazakhstan’s economy—which had only recently seemed on the verge of collapse—earned it a spot among the world’s upper-middle income countries [26]. With some notable exceptions, growth has remained solid since.

These improvements have padded government coffers and sparked ambitious development plans. In late 2012, President Nazarbayev unveiled the Kazakhstan 2050 Strategy [27], an ambitious state plan aimed at making Kazakhstan one of the world’s 30 most developed countries by the middle of this century.

The booming oil economy also drove up demand for professionals with the education and skills to work in the new enterprises. Even today, despite rapid growth in education participation rates, companies still report widespread skills shortages. In 2017, Kazakhstani executives [28] listed an “inadequately educated workforce” as one of the top three obstacles to doing business in the country, after access to financing and corruption. Low unemployment rates back up these concerns. In 2019, unemployment among youths between the ages of 15 and 24 [29] stood at just 3.7 percent, well below the average (12.4 percent) among Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) member states.2 [30] It was even lower for highly educated workers. Unemployment among those with at least a bachelor’s degree or a short-cycle tertiary education was just 3.5 percent in 2017 [31], compared with 5.3 percent [32] among those with an upper secondary education and 6.7 percent [33] of those with an elementary or lower secondary education.

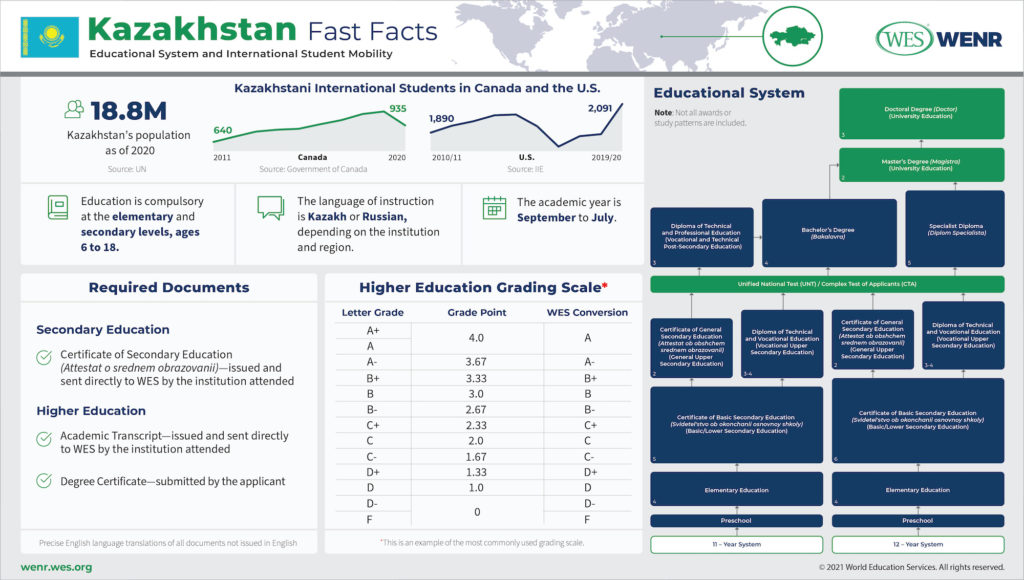

Despite the country’s dramatic economic turnaround, troubles remain. For one, the benefits of growth have not always been evenly distributed. Situated almost entirely in Central Asia, although a Western sliver of land extends past the Ural River into Europe, Kazakhstan is the largest landlocked country and, by land mass, the ninth-largest country in the world. Compared with its size, the country’s population is small, just 18.8 million in 2020 [34], giving it a population density of just 17 people per square mile [35], among the lowest in the world. Kazakhstan’s population is also very unevenly distributed, with a fifth of the population tightly packed into just three cities. Public services and employment opportunities are similarly concentrated in urban areas, resulting in large economic [36] and social disparities between urban and rural communities.

The nature of Kazakhstan’s economic growth—which has largely been driven by its natural wealth—also presents challenges. With oil and related products accounting for nearly three-quarters [37] of the value of Kazakhstan’s exports, rapid and disruptive swings have long plagued the country’s economy, as periodic demand shocks upend the global price of oil. For example, just a few years after the Kazakhstan 2050 Strategy was announced, global overproduction of oil and falling demand [38] caused global oil prices [39]—and Kazakhstan’s economic output—to plummet. Annual GDP growth fell from 4.2 percent in 2014 to just a little more than 1 percent in 2015 and 2016.

The dangers of overdependence on petroleum exports have given new urgency to the government’s ongoing economic diversification efforts. Already in the Kazakhstan 2050 Strategy, the government had pledged to make its economy more diversified and knowledge based [40]. Much of that will be driven by education reforms. The strategy prioritizes “supporting youth, education, and innovative research [41],” and calls for the creation of “an education system that promotes the growth of the nation.”

These reforms will build on those of the past. Since the start of the twenty-first century, growing revenues have allowed the government to devise ambitious reforms aimed at improving education and teaching quality, expanding access to poorer students, and aligning the system with international norms. But to fully transform and diversify its economy, the country will need to provide more support to its education system. In its latest report [42] on the progress of Kazakhstan’s transition to a market economy, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) identifies the need to “improve inclusion across regions and for vulnerable population groups” as one of the country’s key priorities in 2021. In elaborating on how those improvements can be achieved, the report is unequivocal: “Reforms in education and vocational education need to accelerate.”

International Student Mobility

Recent developments in Kazakhstan have placed a premium on global awareness and engagement. In response, the government has attempted to cultivate international educational connections by promoting international student mobility, both into and out of Kazakhstan, and encouraging the internationalization of its higher education system.

In its Academic Mobility Strategy in Kazakhstan 2012-2020 [43], the primary policy document governing the country’s internationalization strategy over the past decade, the government laid out a series of bold internationalization goals. These included having one in five Kazakhstani students engage in some form of study abroad by 2020, and increasing the number of international students studying at Kazakhstani universities by 20 percent each year. Improving the English language skills of students and faculty, expanding the number of programs offered in foreign languages, and promoting links with foreign universities and international organizations were also identified as objectives in the strategy.

The government has backed these plans with concrete actions. It has funded generous international scholarship programs, issued directives requiring institutions to establish international academic partnerships, and joined intergovernmental higher education initiatives, most notably, those associated with the Bologna Process.

The Bologna Process

Kazakhstan’s gradual implementation of the principles underlining the Bologna Accord, which Kazakhstan joined as a full member in 2010 [44], has had a significant impact on international student mobility. The government has moved to harmonize its education system with those of other members of the European Higher Education Area [45] (EHEA), introducing a three-cycle (bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral) qualifications structure and encouraging universities to adopt the European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS), both of which are discussed in more detail below. These changes have increased intraregional credential recognition and portability, promoting student mobility between Kazakhstan and other EHEA member states.

Kazakhstan’s joining of the Bologna Process has also helped spur the proliferation of international academic and institutional partnerships, an explicit goal of the government, which now requires all universities to establish international partnerships. By the 2020/21 academic year [46], Kazakhstani universities had signed nearly 6,800 agreements with international partners in 85 countries. The vast majority of these agreements were signed with institutions in other EHEA member states.

Aside from increasing student and scholar mobility, the government hopes that these collaborations will help improve the knowledge and skills of domestic faculty and modernize academic courses and programs. Also helping to further these goals are a growing number of transnational education (TNE) programs, most notably joint and dual degree programs, which allow students to complete part of their studies at a Kazakhstani university and part at an international partner institution. In 2020/21, Kazakhstani universities offered 108 double degree or joint education programs with international partner institutions.

The Bolashak International Scholarship

The government of Kazakhstan also relies on publicly funded scholarships to help further its internationalization goals. Since 1993, the most important has been the Bolashak International Scholarship [47], which the British Council described as the “best scholarship program in the world [48]” at its 2014 Going Global Conference.

The government’s goal for the program is partially revealed by its name, “Bolashak,” which translates into English as “future.” The presidential decree establishing the scholarship states [49] that “Kazakhstan’s transition towards market economy and expansion of international contacts requires personnel with the advanced western education, and it is now necessary to send the most talented youth to study at the top-ranking universities abroad.”

The Bolashak scholarship aims at developing specialists in fields of public importance by funding the education of top students at prestigious overseas universities on the condition that they return to Kazakhstan and work for a minimum of five years after graduation. In exchange, the government pays for the full cost of their overseas studies, covering everything from tuition and books to travel, housing, and other living expenses. The scholarship also funds pre-degree English language training, professional internships, and non-degree training programs in critical fields. Between 1993 and 2017, the government awarded nearly 13,000 Bolashak scholarships [50].

The scholarship is administered by the JSC Center for International Programs [51], part of the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan (MESRK). Eligibility criteria have varied widely over the course of the scholarship’s existence. Since 2011 [52], the scholarship has only funded post-graduate degree programs. In 2014, the center further restricted eligibility by increasing the minimum qualifying International English Language Testing System (IELTS) score and limiting the scholarship to students accepted at universities ranked in the top 200 on the QS World University Rankings [53], the Times Higher Education World University Rankings [54], or the Academic Ranking of World Universities [55].

In collaboration with student representatives, universities, and employers, the JSC Center also determines the specialties that are eligible for scholarship funding. Published data [56] suggest that most Bolashak recipients pursue programs in fields important to the government’s social, economic, and political goals, such as information technology, oil and gas development, pedagogy, petrochemicals, political science, and public administration.

Outbound Mobility

But government funding alone is not solely responsible for the large number of Kazakhstani students studying overseas each year. In 2014, experts estimated that government scholarships funded the studies of only 30 percent [57] of all Kazakhstani students enrolled abroad. The remainder were likely paying out of pocket, a possibility open to growing numbers of Kazakhstani students and their families as the country’s economy and middle class expand.

Those able to afford an international education are likely further pushed to study abroad by a lack of seats at high-quality domestic institutions and by the reports of corruption that have plagued Kazakhstan’s higher education system for decades. The promise of a higher quality education overseas likely attracts a significant proportion of Kazakhstani students who would have otherwise remained at home. In fact, few Kazakhstani international students remain overseas after graduation. Education agents working in Kazakhstan [58] estimate that around seven in ten Kazakhstani students return home immediately after completing their studies.

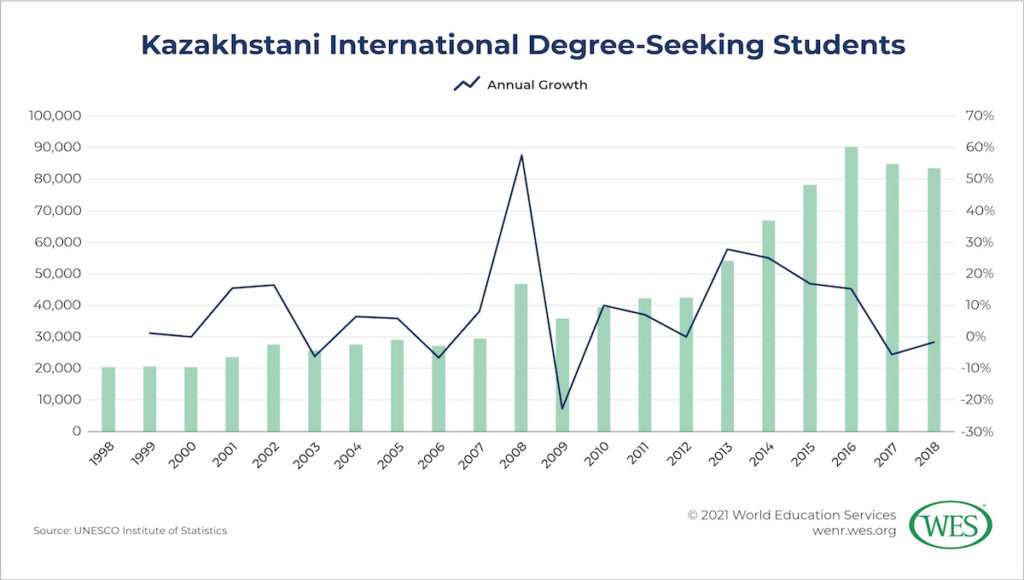

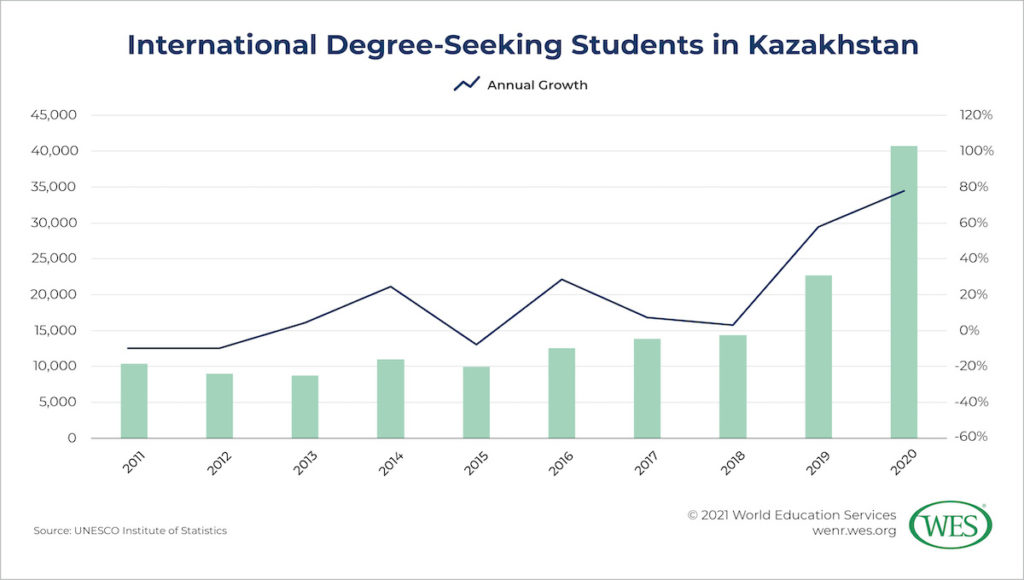

This combination of factors has made Kazakhstan a major source of international students worldwide. In 2018, Kazakhstan was the eighth-largest source of international degree-seeking students globally, according to data compiled by the UNESCO Institute of Statistics [59] (UIS).3 [60] That year, 83,503 Kazakhstani students were studying outside the country. Growth over the past decade has also been particularly impressive. Since 2009, outbound mobility has more than doubled, peaking at 90,213 in 2016 before declining slightly over the past two years.

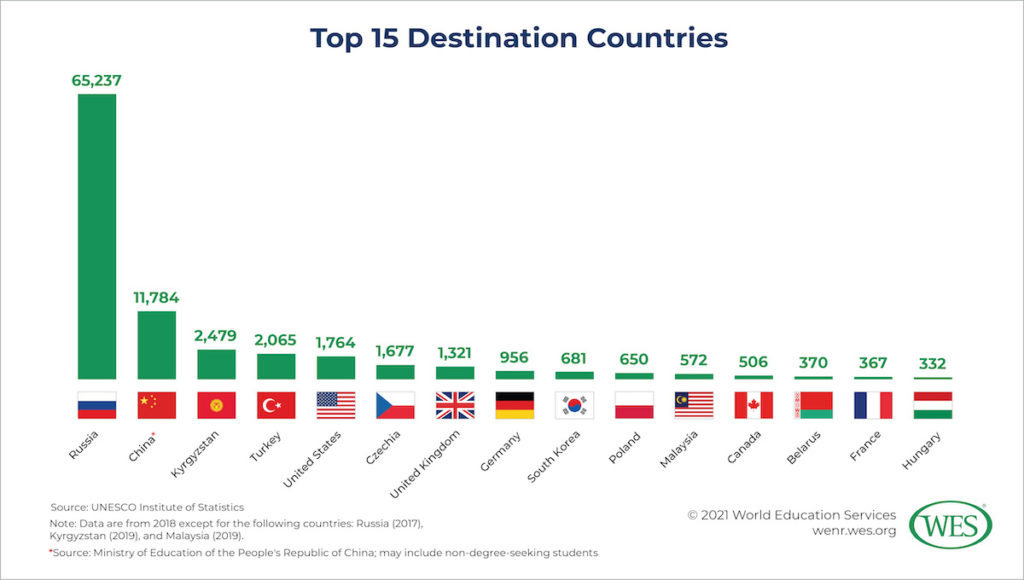

Still, although many Kazakhstani students are willing to cross the country’s borders to study, most stop immediately on the other side. The vast majority of outbound Kazakhstani students are enrolled in countries directly bordering Kazakhstan, most notably Russia and China. Combining UIS data with the latest numbers provided by China’s Ministry of Education suggests that more than eight in ten international Kazakhstani students were enrolled in one of those two countries.4 [62]

Russia and China

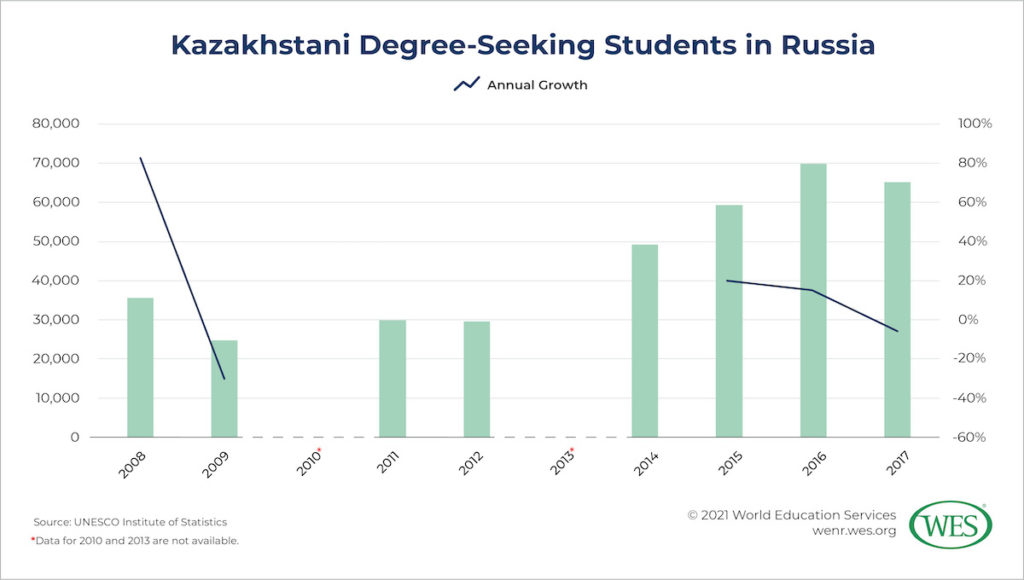

Kazakhstan has long been the leading source of international students in Russia. In 2017, the latest year for which the relevant UIS data [64] is available, Russia hosted 65,237 Kazakhstani students, more than triple the number of Uzbek students (20,862), who make up the next largest contingent of international students in Russia.

Unsurprisingly, the educational connection between Kazakhstan and Russia has a long history. For decades, the government of the Soviet Union [65] supported a unique system of international education and exchange, providing full funding to certain students from constituent republics to study at academic institutions in other Soviet republics, most often in the Russian Federation. After its dissolution, the connection between former Soviet republics continued. In 1998 [66], Kazakhstan signed a joint agreement with Belarus, the Kyrgyz Republic, and Russia (Tajikistan joined in 2002 [67]) that aimed at deepening “multilateral cooperation in the fields of education, sciences and cultures” and “setting standards of mutual recognition of education documents, academic degrees and ranks.”

Kazakhstan also cooperates closely with Russia politically, militarily [68], and economically. Kazakhstan, alongside Belarus and Russia, was a founding member of the Eurasian Economic Union [69] (EAEU), an integrative alliance that seeks to promote the free movement of goods and services between a number of East European, Western Asian, and Central Asian countries. The Russian government [70] has also made attracting international students a linchpin of its “soft power” offensive in former Soviet republics, offering scholarships to talented Kazakhstani students [71], waiving student visa requirements [72], and allowing applicants to substitute a “tailor-made [73]” university entrance examination for Russia’s national university admissions examination, the Unified State Exam. In late 2020, Russia also eased rules [74] regulating international students’ eligibility to work in the country while studying.

Russian institutions also play a prominent part in transnational education (TNE) in Kazakhstan. In the 2020/21 academic year, Russian universities accounted for a third of all international agreements [46] signed by Kazakhstani universities, the highest of any country by far. Although data are unavailable, these collaborative programs likely funnel Kazakhstani students to colleges and universities located in Russia. Other factors, including geographic proximity, cultural and linguistic similarity (more Kazakhstani citizens speak Russian than Kazakh), and the ready availability of affordable and high-quality institutions, likely also attract Kazakhstani students to Russia.

China is also an increasingly prominent destination for Kazakhstani students, although available numbers are not strictly comparable. According to the Institute of International Education’s (IIE’s) Project Atlas [76], the number of Kazakhstani students studying in China more than doubled in the decade prior to the 2015/16 academic year, growing from 5,666 in 2006/07 [77] to 13,996 in 2015/16, before declining to 11,784 in 2017/18.

China’s continued growth as an international student destination has been bolstered by quality improvements at the nation’s universities and by ambitious government-funded projects, including the Belt and Road Initiative [78] (BRI), an abbreviation of the project’s official name: the Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road. Given Kazakhstan’s prominent location on the ancient Silk Road, it is perhaps unsurprising that the Chinese government has directed some of its outreach toward the country, funding the establishment of Confucius Institutes in Kazakhstan [79] and financing scholarships for Kazakhstani students to study in China.

The United States and Canada

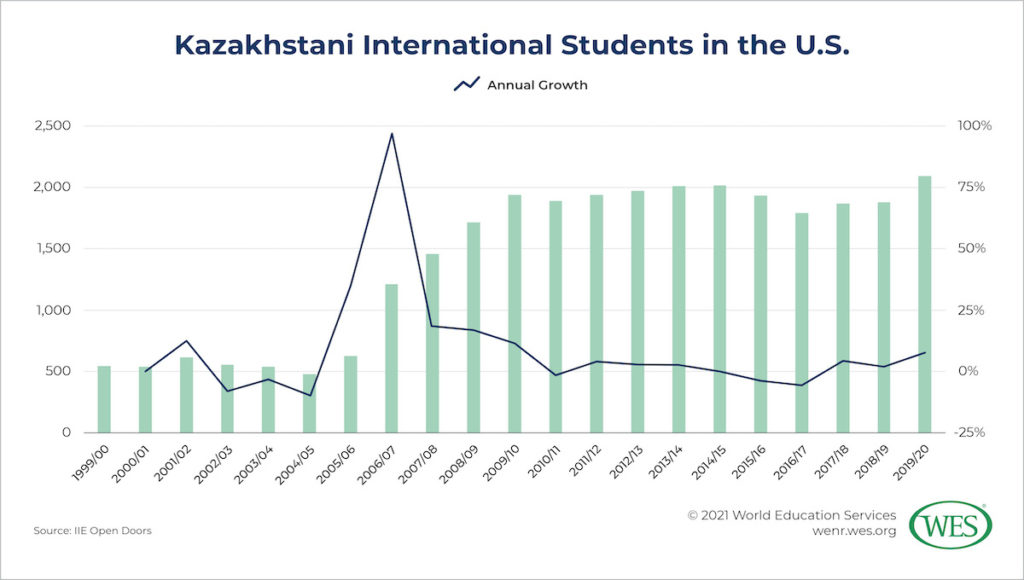

Kazakhstani enrollments in the Western Hemisphere lag sharply behind those in the East. In the United States, they also show few signs of growth. After more than tripling between 2004/05 and 2009/10, when it reached 1,936, enrollment has barely budged since. Just 2,091 Kazakhstani students were enrolled in U.S. higher education institutions in the 2019/20 academic year, according to IIE’s Open Doors report [80]. A plurality (44 percent) of these students are currently enrolled at the undergraduate level [81], with 35 percent registered in graduate programs, 8 percent in non-degree programs, and 13 percent in the Optional Practical Training (OPT) program.

Several reasons likely account for these low numbers, including an abundance of high-quality universities located closer to home, the high cost of colleges and universities in the U.S., and the generally low levels of English proficiency among Kazakhstani students. Despite a strenuous government effort to promote English language competence, introduced by President Nazarbayev in the 2007 Trinity of Languages [83] program, overall English language proficiency in Kazakhstan remains low. The EF English Proficiency Index [84] (EPI) has ranked Kazakhstan in the lowest English proficiency band every year since 2011. Education agents working in Kazakhstan confirm these assessments, reporting that most Kazakhstani students have weak English language skills [85] and usually require preparatory English training before beginning their full-time studies.

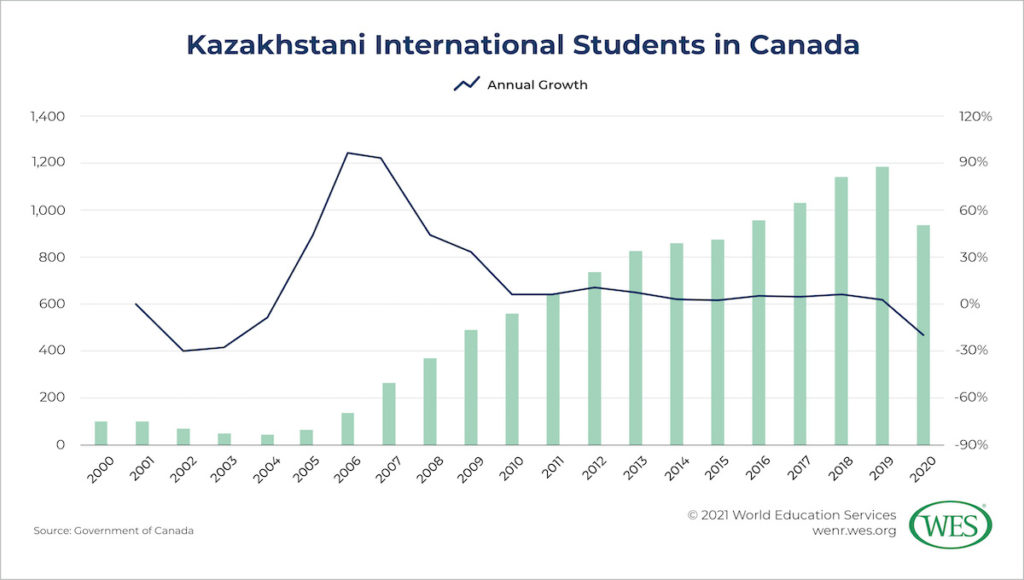

Despite the two countries’ sharing many of the same challenges, Canada’s experience differs sharply from that of the U.S. While still low compared with Kazakhstani enrollments in Russia and China, enrollment in Canada has grown steadily after reaching a nadir of just 45 Kazakhstani students in 2004. According to statistics from Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) [86], enrollment growth has averaged more than 9 percent a year over the past decade, reaching 1,195 in 2019. This trend is hardly unique to Kazakhstani enrollments: Canada’s high-quality and relatively low-cost institutions as well as the country’s more welcoming policies toward both international students and internationally educated immigrants have been attracting growing numbers of students from around the world for years.

Inbound Mobility

For decades, Kazakhstan attracted relatively few international students. Developing its native-born workforce was long the government’s primary reason for promoting internationalization, so it naturally placed far less emphasis on increasing inbound student mobility than it did on boosting outbound flows.

The poor reputation of Kazakhstan’s higher education system also did little to attract international students. A 2017 review by the OECD [88] of Kazakhstan’s higher education system identified a handful of factors discouraging international students from studying in the country, including the generally poor condition of Kazakhstan’s university facilities and services, widespread corruption, and a lack of programs offered in English.5 [89] The OECD report concludes that, “While it may be possible to increase inbound student numbers by working more closely with aid agencies, until the quality and integrity of higher education are demonstrably improved, substantial increases are unlikely.” As a result, Kazakhstan’s average inbound mobility ratio between 2010 and 2018 stood at just 1.6 percent, well below the world average (2.2 percent), according to UIS data [90].

But over the past two years, this picture has changed dramatically. Between 2018 and 2020, the number of international students enrolled in Kazakhstan expanded sharply, growing 184 percent, from 14,332 in 2018 to 40,742 in 2020 [91]. In 2019, its inbound mobility ratio rose to 3.32 percent, an all-time high.

This transformation coincided with a renewed push by the government to attract international students. In early 2018, MESRK announced [92] its plans to transform the country into a “Central Asian educational hub,” setting an ambitious goal of attracting 50,000 international students by 2022.

Data suggest that MESRK’s focus on Central Asia has paid off. Kazakhstan attracts more international students from around the world than any other country in Central Asia. Students from other Central Asian countries also make up the majority of all international students in Kazakhstan. In fact, most of the recent uptick in international students studying in Kazakhstan was driven by an increase in enrollments from Uzbekistan. Between 2018 and 2020 alone, the number of Uzbek students in Kazakhstan grew nearly sevenfold, rising from 3,768 in 2018 to 26,130 in 2020 [64].

But there are signs that that rapid expansion could prove short-lived. Recently, Uzbekistan has introduced important reforms to its own higher education system, significantly expanding the number of seats and public grants available at the country’s long overcrowded universities. More controversially, government officials have publicly encouraged Uzbek students enrolled abroad to return home [94], even going so far as to exempt returning students from national university entrance examinations. While it remains to be seen exactly what impact these changes will have on Kazakhstan’s inbound student numbers, early reports [95] suggest that it could be severe.

Outside of Central Asia, India is a significant source of international students in Kazakhstan. Over the past five years, Indian student enrollment has grown by 159 percent, rising from 1,716 in 2016 to 4,453 in 2020. Much of that growth is driven by the demand of Indian students for a medical education, which in India is expensive [96] and hard to access. Even if India’s recent medical reforms [97] manage to increase the country’s ability to train its own medical students, growing political, economic, and cultural cooperation [98] between Kazakhstan and India bode well for the future.

Kazakhstan’s growing popularity lends credence to some of the more optimistic projections of the country’s future role in international student mobility. In a 2012 paper [99], Geoffrey David Wilmoth, director of the education consulting firm Learning Cities International [100], argues that Kazakhstan is well poised to transform itself into an international education hub if it can successfully reform its higher education system.

In Brief: The Education System of Kazakhstan

Like the country as a whole, education in Kazakhstan is in transition. Despite decades of government efforts aimed at modernizing and internationalizing the education system, the imprint of its Soviet past remains prominent.

Much of that inheritance is positive. During the Soviet era, the state invested heavily in education, establishing a solid network of kindergarten, elementary, and secondary schools. As a result, literacy and enrollment rates skyrocketed—in 1990, one year before independence, the Kazakh SSR’s elementary gross enrollment ratio stood at 116 percent. The Soviet state also did much to develop higher education in the republic, leaving Kazakhstan 55 universities upon independence.

Still, Soviet-era education had significant shortcomings. Although overall enrollment rates expanded rapidly, access for many rural Kazakhstanis, especially to secondary and post-secondary education, remained limited. At the country’s universities, rigid teaching practices, a narrow focus on developing technical skills, and limited research capacity hampered quality. Strong centralized control over all levels of the education system also made it difficult for educators and administrators to adapt their practices to local conditions or changing circumstances. Finally, upon independence, Kazakhstan’s Soviet past left its education system isolated internationally, as the unique structure of Soviet qualifications diverged sharply from international, or at least Western, standards.

The turmoil of Kazakhstan’s first decade of independence added significantly to the challenges its education system faced. With the economy and public revenues collapsing, the government moved quickly to shift the responsibility for education funding from the public purse to private pockets, rushing through measures to privatize the ownership and financing of education. As a result, low-quality private institutions proliferated. Between 1995, the first year for which data are available, and 2004, government funding for education as a percentage of GDP [101] collapsed, falling from 4.03 percent to 2.26 percent.

These initial disruptions had varying effects on different levels of the education system. Some, such as pre-elementary and technical and vocational education, were hit hard—institutions rapidly shuttered and enrollment dropped sharply. Other levels were impacted far less, at least in the short term. Starting in the early 2000s, the effects of the demographic contraction of Kazakhstan’s first decade of independence led to declining enrollments across the board.

The early 2000s also brought with them a dramatic change in the fortunes of Kazakhstan’s education system. Growing oil wealth expanded the government’s reform capacity, allowing it to embark on a series of sweeping education reforms. With varying levels of success, the government introduced measures aimed at aligning the country’s qualifications framework with EHEA standards and extending the elementary and secondary school cycle to 12 years. With respect to higher education, government officials adopted an “optimization policy” geared toward eliminating the low-quality institutions established since independence.

The results have been impressive. In 2011, Kazakhstan was ranked first worldwide on UNESCO’s Education for All Development Index [102] (EDI), which measures elementary enrollment and completion rates, adult literacy levels, and gender parity in education and literacy. Today, enrollment in elementary and secondary education is nearly universal, with negligible differences in access and achievement by gender. International organizations, such as the OECD [103], have also praised the Kazakhstani education system for its low repetition rates. Most Kazakhstani students progress smoothly from one grade to the next, with few held back.

But education in the republic still faces significant challenges. Kazakhstani students perform poorly on international standardized assessments, and the country’s high EDI ranking belies large regional and socioeconomic disparities in educational access and achievement. These challenges are exacerbated by low levels of government support for education. Despite the economy’s rapid growth, education funding remains low, reaching just 2.6 percent [104] of GDP in 2018, well below the OECD average (around 5 percent), leaving school infrastructure in much of the country inadequate and underdeveloped. And despite recent changes, the country’s highly centralized system of administration and governance has long challenged Kazakhstan’s educators and reformers.

Administration of the Education System

Kazakhstan is a unitary republic comprising 18 principal administrative divisions: 14 regions [105] (oblyslar in Kazakh and oblasts in Russian) and four special status cities [106]6 [107] which possess the same degree of administrative and political autonomy as the oblyslar that surround them. Oblyslar are divided into more than 170 districts, or rayons, which are further subdivided into thousands of villages and rural communities. Despite the recent introduction of decentralization reforms [108], Kazakhstan’s central government retains tight control over regional and local authorities, with the president appointing regional governors (akims), the highest regional executive officers, to lead oblyslar and special status cities.

Governance of the education system is similarly centralized. Presidential orders, acts of parliament, and ministerial decrees issued from the nation’s capital tightly regulate all levels of the country’s education system. The 2007 law On Education [109], plus its 2011 and 2015 amendments, defines the current legal framework governing education in Kazakhstan. Education delivered throughout the country must conform to the law’s decrees.

Since independence, the Executive Office of the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan [110] and the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan [111] (MESRK) have assumed primary responsibility for education administration. The Office of the President develops high-level education objectives and manages major projects, spearheading special initiatives like the Nazarbayev Intellectual Schools (NIS) and Nazarbayev University, discussed in more detail below. The president also plays an important role in developing the nation’s education policies, which are laid out in comprehensive state programs. Over the past decade, two state programs have been particularly decisive: the State Programme of Education Development in the Republic of Kazakhstan for 2011-2020 [112] (SPED 2011-2020) and the State Programme of Education Development in the Republic of Kazakhstan for 2016-2019 [113] (SPED 2016-2019).

MESRK’s responsibilities are more wide-ranging, including funding and management of the entire education system as well as its strategic planning. As the nation’s central education authority, MESRK also assumes primary responsibility for ensuring that the education laws and state education programs are implemented throughout the country.

In addition, MESRK regulates course content and program design. At all levels of education, from preschool to higher education, both public and private institutions are required to follow the standards and curriculum guidelines outlined in State Compulsory Standards7 [114] (SCS). Developed by the National Academy of Education (NAE), an agency of MESRK, SCS prescribe compulsory subjects [115], teaching methods, and educational programs. The latest SCS—updated in 2017 [116]—seeks to address criticism leveled by, among others, the OECD in its 2018 Education Policy Outlook [117], that previous curricula focused too much on rote memorization, by instead emphasizing competencies, such as “critical thinking and creativity.”

While MESRK has historically played an important role in curriculum development at the higher education level, since Kazakhstan joined the Bologna Process, it has begun to concede more and more control over content and courses to accredited institutions. As of 2015, higher education institutions were able to determine 55 percent [118] of program content in bachelor’s programs, 70 percent in master’s programs, and 90 percent in doctoral programs.

MESRK is also responsible for licensing and attesting institutions teaching at any level of education, ensuring institutional compliance with relevant legislation, and assessing student learning outcomes. Until 2021 [119], MESRK, like many other post-Soviet education ministries, even regulated the format of diplomas earned at all public universities and at private universities accredited by a registered, independent accreditation agency [120].

Prior to independence, the government was entirely responsible for financing education. That changed rapidly in the early 1990s when the government legalized private ownership of educational institutions and introduced tuition fees at public universities. In recent years [118], around 29 percent of university students received state-funded grants; the rest paid out of pocket. At the elementary and secondary levels, the government recently introduced a per capita funding scheme, under which the amount of public funding a school receives will be determined by the number of students it enrolls. The government hopes that the new funding scheme will prompt school administrators to improve educational facilities and teaching quality, as schools compete for students and the government funding that comes with them.

While the government has long maintained tight control over all levels of education, recent reforms have attempted to decentralize education administration. To expand stakeholder engagement, governing boards of trustees were introduced in elementary and secondary schools and public universities in 2007. In schools, these boards are made up of parents and community representatives, although as of yet they play only a limited role in school governance. University boards, composed of public and private sector representatives, also lack significant operational autonomy, functioning mostly in an advisory capacity.

The 12-Year Compulsory Education Reform

The government has also embarked on expansive reforms aimed at modernizing the quality and structure of the country’s education system, among the most important of which is the extension of school education from 11 to 12 years. Still ongoing, the reform’s stalled implementation illustrates the challenges faced by Kazakhstani policymakers in modernizing the country’s education system.

The government first moved to update the elementary and secondary school cycle in the early 2000s. In 2001 [121], MESRK announced its intention to extend the education cycle from 11 to 12 years to better align the country’s education system with international norms. The reform would build on those of the country’s Soviet past; in 1985 [122], Mikhail Gorbachev, then the leader of the Soviet Union, introduced reforms that lengthened school education in all Soviet republics from 10 to 11 years. In the state education program adopted in 2004, SPED 2005-2010 [123], the government set a completion date of 2010.

But since it was first announced, implementation of the 12-year cycle has been repeatedly postponed, in large part, because of insufficient government funding. The SPED 2011-2020 attributed the delays to “insufficient material and technical resources, educational and methodical base, as well as the necessity of updating the content and methods of education.” It also laid out a new, staggered implementation schedule, set to begin in the 2015/16 academic year with grades 1, 5, and 11 and to end in 2019/20 with all grades operating under the 12-year system.

However, in late 2014, the collapse in global oil prices and falling government revenues forced MESRK to push the timeline back once more [124]. As before, the need to develop a new curriculum; to print, distribute, and train teachers in the use of new textbooks; and to construct new learning facilities capable of handling an additional year of teaching held back reforms. The Minister of Education and Science stated [125] in late 2019 that, “Our landmark is 2021. We are planning and are now laying in the draft national program.” In early 2021, MESRK announced [126] that gradual implementation of the 12-year cycle would begin in 2023.

When finally implemented, the reform will add an additional year to the start of a student’s academic career, lowering the age at which students are required to begin elementary education from 7 to 6, while leaving the typical age at which students graduate from secondary school (age 17 or 18) unchanged. Although nationwide implementation has long been delayed, the 12-year cycle has been rolled out experimentally in a limited number of schools throughout the country. In 2012, it was piloted in over 100 schools. In 2015/16, 30 more were added, among them, Nazarbayev Intellectual Schools (NIS).

Academic Calendar and Language of Instruction

Kazakhstan possesses a rich mosaic of ethnicities and languages [127]. Its two largest ethnic groups [128] are Kazakh (63 percent) and Russian (24 percent). Its lengthy immersion in Russia’s sphere of influence, which long predates its absorption into the Soviet Union, has had a profound impact on the languages spoken throughout the country. Three decades after independence, more people in Kazakhstan speak Russian (94 percent) than Kazakh (83 percent), a Turkic language and the native language of the Kazakh people.

Kazakhstan’s language policies have evolved considerably in the decades since the country declared its independence. As part of Kazakhstan’s attempt to forge a unified national identity, the newly independent government initially promoted the spread of the Kazakh language, officially elevating it above all others. The country’s 1995 constitution [129], its second post-independence constitution, established Kazakh as the official national language, even going so far as to require that the president possess “a perfect command” of the Kazakh language. It accorded Russian less importance, granting it official status only in public institutions, where Russian was to be used on “equal grounds” with Kazakh.

More recently the government has pursued a trilingual policy [130] aimed at increasing the population’s proficiency in Kazakh, Russian, and English. In recognition of English as the lingua franca of international business and trade, the policy set a goal of expanding the percentage of Kazakhstani citizens speaking English to 20 percent and the percentage speaking all three languages to 15 percent by 2020. Among other measures, the policy calls for expanding the share of government language training centers offering English language courses. While data suggest that the policy’s goals have been reached, with the CIA World Factbook [131] estimating in 2017 that around 22 percent of the population speaks all three languages, as noted above, other organizations rate the country’s average English proficiency very low.

In line with state policy, MESRK has promoted the use of English in the country’s schools and universities, especially in the teaching of science, technology, and engineering subjects. Over 150 schools have introduced English as the language of instruction for biology, chemistry, information technology, and physics in grades 10 and 11, while hundreds of others offer optional courses and activities conducted in English. MESRK has also begun to organize English language training programs for teachers in these fields, rewarding those who achieve a high level of English competence with a pay bump. Policymakers are also hoping to introduce the next generation of students to English early. In 2016, English was made a compulsory subject at the preschool level.

Other significant linguistic reforms are underway in Kazakhstan. In 2017, President Nursultan Nazarbayev announced a gradual switch [132] from a Cyrillic to a Latin alphabet in the writing of Kazakh, to be completed by 2025. Officials contend that the change is “part of a modernization drive and an attempt to make use of technology easier” and that it will “benefit Kazakhstan’s development” to adopt an alphabet used by 70 percent of the world. Implementation has since been delayed, with the government now hoping to complete the transition by 2031 [133]. In the education system, the new alphabet will be introduced gradually as the country updates its textbooks in preparation for the implementation of the 12-year education model.

Although Kazakhstan’s 1995 constitution guarantees its citizens the right to “freely choose the language of communication, education, instruction and creative activities,” since independence, most educational institutions have offered instruction in either Kazakh or Russian. Naturally enough, the language of instruction used in a school or university typically mirrors that spoken most frequently by members of the community served by the school. Since independence, the use of Kazakh in schools and universities has grown. In the early 2000s, Russian was used as the language of instruction in universities 58 percent [134] of the time; Kazakh, 40 percent; and Uzbek, around 1 percent. More recently, those percentages have been reversed. At the beginning of the 2020/21 academic year [135], 65 percent of university students were enrolled in programs taught in Kazakh, 29 percent in Russian-taught programs, and around 6 percent in English-taught programs.

At the elementary and secondary levels, the numbers are similar. More than half [136] (51 percent) of general day schools, which teach all elementary and secondary grades, teach in Kazakh, while just 17 percent teach exclusively in Russian; 31 percent offer instruction in both Kazakh and Russian. Despite educating a majority of the country’s children, learning outcomes at Kazakh-medium schools lag those of their Russian-language counterparts. Results from the OECD’s 2012 Program for International Student Assessment [137] (PISA) revealed large disparities in performance, with students in Kazakh-medium schools performing well behind their peers in Russian-medium schools.

No matter the language of instruction, the academic calendar in schools and universities throughout Kazakhstan typically runs from September to May or June. The elementary and secondary school year lasts for a maximum of 34 weeks and is typically divided into quarters. At higher education institutions, the academic year usually extends over 36 weeks, consisting of two semesters of 15 weeks plus breaks, although some institutions operate on a trimester or quarterly system.

Early Childhood Education

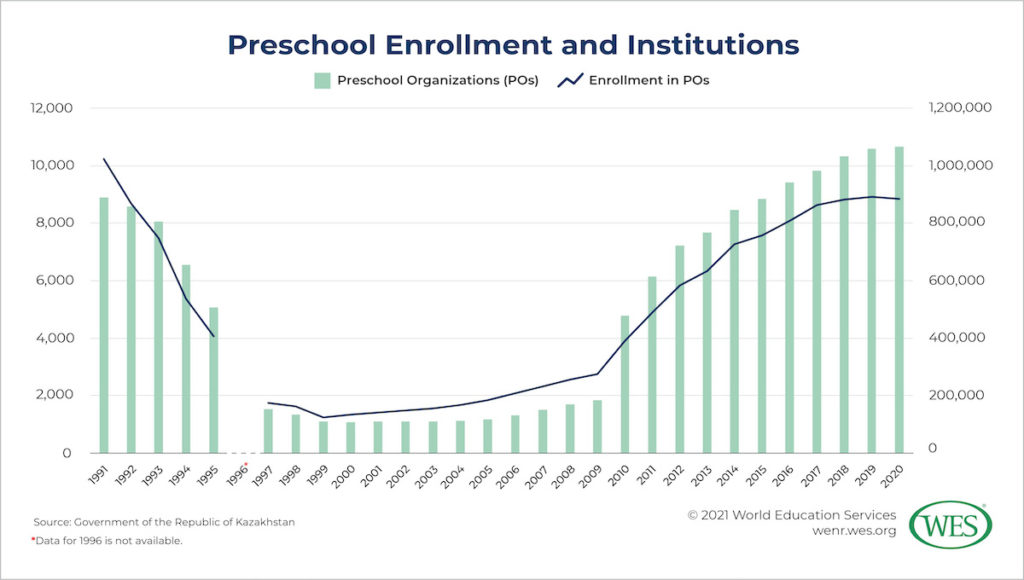

Of all stages of its education system, the turbulence of Kazakhstan’s first post-independence decade hit early childhood education (ECE) the hardest. In less than a decade, the well-organized preschool system inherited from its Soviet past almost completely collapsed, as government support dried up [138] and the agricultural and industrial enterprises which ran many preschools closed. Preschool organizations (POs), which include a variety of institutions providing both childcare and pre-elementary education to children between the ages of 1 and 6 or 7, declined 88 percent between 1991 and 2000, from 8,881 to 1,089, according to government statistics [139]. The enrollment decline was just as dramatic, falling from a peak of more than 1 million in 1991 to a bit less than 125,000 in 1999. The pre-elementary gross enrollment ratio [140] (GER) fell from 82 percent to 15 percent over the same period.

Kazakhstan’s economic turnaround stemmed much of the bleeding, and enrollment levels remained more or less stable for the first decade of the twenty-first century. They began to take off around 2010, as the government turned its attention, and its growing tax receipts, toward ECE, focusing in particular on the year just before the start of elementary education. The Kazakhstan 2050 Strategy explicitly identified ECE as a priority, and the SPED 2011-2020 set a goal of expanding ECE enrollment to all children between the ages of three and six by 2020.

While that goal was not attained, the results have nonetheless been impressive. Enrollment in POs reached nearly 900,000 in 2019, a twenty-first century high. The following year, although absolute enrollment numbers declined slightly, the pre-elementary GER rose to 74 percent. While this growth has been remarkable, that Kazakhstan’s preschool enrollment numbers still trail their pre-independence peak reveals the depth of the disruption caused by the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

Today, access to ECE for all children ages one to six is a right guaranteed by the government. Parents can enroll their children in a number of different types of POs [142], both public and private. Most children attend kindergartens, which are divided into nursery kindergartens, attended by children between the ages of one and three, and regular kindergartens, attended by children ages three to six. The next most popular category of ECE provider is the preschool mini-center, introduced by the government to expand rural access. To accommodate rural conditions, MESRK grants mini-centers a high degree of flexibility, allowing them to shorten the school day or to operate from unconventional locations, such as community centers or private homes.

MESRK tightly controls the content of education provided at both public and private POs. It has approved four separate sets of curriculum guidelines for different age groups, each of which prescribes the subjects that must be taught and the materials, down to the books and toys, that can be used. Since 2016 [143], English has been a mandatory subject in preschools for children over the age of five. Unsurprisingly, domestic and international experts, including those drafting a 2017 OECD review [144] of Kazakhstan’s ECE system, have criticized these arrangements as inflexible.

Despite efforts to expand access, that same 2017 OECD review identified “geographical, socio-economic, and special needs inequities regarding access to and participation in ECE.” In theory, enrollment in public preschools is free [145] for three years [146], during which parents are responsible only for the cost of their child’s lunch. Instead of relying on private fees, both public and private preschools should receive adequate funding from the government, which currently determines the level of public funding each school receives by the number of students they enroll. But the OECD’s review found that the efficiency of this per capita funding scheme, while admirably intentioned, has been hampered by poorly calibrated funding levels, which have forced POs to charge parents to cover basic operational expenses. As a result, many Kazakhstanis still pay significant fees out of pocket. In 2010, the lowest income quintile spent, on average, a shocking 45 percent of their household expenditure on ECE, which the report concludes likely accounts for the low enrollment ratios for that quintile, just 19 percent of whom attended ECE.

Data also reveal regional disparities in access and enrollment. In a reversal of typical trends in Kazakhstan, ECE coverage in urban communities lags that of rural areas. The OECD’s 2018 Education Policy Outlook notes that regional rates of ECE participation for children over age 3 were lowest in the country’s two largest cities: Almaty and Nur-Sultan.

Further support of the ECE system could pay dividends. This same OECD policy brief notes that even after controlling for socioeconomic background, Kazakhstani students who had attended preschool for more than one year scored 11 points higher on the PISA 2012 than those who had never attended at all.

Elementary Education

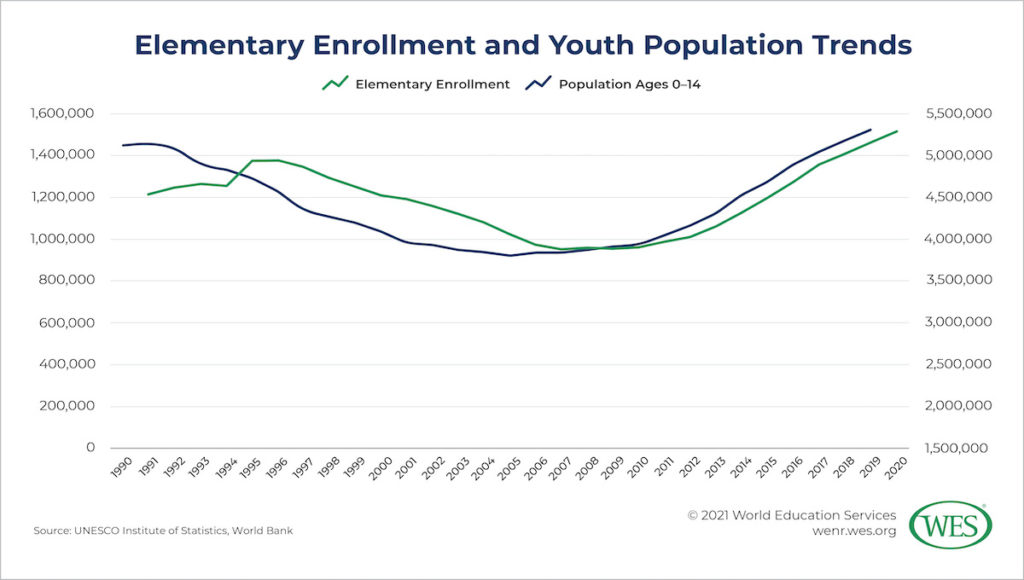

In the short term, the chaos of the initial years of post-independence impacted elementary enrollment far less than it did preschool enrollment. Between 1990 and 1996, when enrollment peaked at nearly 1.4 million, growth was positive in every year but one, according to UIS data [147]. Although the elementary GER [148] did decline, the lowest it ever fell was 96 percent, which it reached in 1999.

Instead, the demographic contraction of that first decade had a delayed impact on enrollment levels. Starting in 1997, elementary enrollment began a more than decadelong decline, falling to a low of less than 950,000 in 2007. The rise in birthrates, which began in the early 2000s, eventually reversed the decline. Elementary enrollment has increased steadily since 2010, growing by more than half by 2020, when it exceeded 1.5 million.

Public school education—elementary and secondary—in Kazakhstan is compulsory and available free to all Kazakhstani citizens and has been since the adoption of Kazakhstan’s current constitution in 1995. Prior to 2020, students typically entered elementary school at the age of seven, although students passing an entrance examination could begin a year earlier. As of 2020, all students must begin elementary education, which lasts for just four years (grades 1 to 4), at the age of six, an adjustment aimed at keeping the typical age of graduation from upper secondary school the same following the country’s transition to a 12-year education model.

The elementary curriculum [116] is organized around a handful of educational fields, including language and literacy, mathematics and computer science, natural sciences, man and society (which aims at “studying the social phenomena of the past and present and their interrelations”), technology and art, and physical education. Students must study two languages: one native, such as Kazakh, Russian, or another local language; and one foreign language, typically English. Instructional hours at the elementary level are currently capped at 29 hours per week.

Lower Secondary Education

Secondary education is divided into two phases: lower, which is known in Kazakhstan as basic secondary education, and upper, which is known as senior or general secondary education. In Kazakhstan, the phrase “general secondary education” is not used exclusively to refer to the final phase of secondary education; it is often also used to refer to the entire cycle of school education, from grades 1 to 11 or 12.

Under the 11-year system, basic secondary education lasts for five years, spanning grades 5 to 9. Under the 12-year system, lower secondary education will be extended by one year, lasting from grade 5 to grade 10. The subjects taught under the 12-year system will differ little from those taught under the old system. Currently, the basic secondary education curriculum includes arts, computer sciences, history, languages and literature, mathematics, natural sciences (such as physics, chemistry, biology, and geography), and physical education. After completing the required period of study, students take a final attestation [150], or final certification, exam. Students passing both their coursework and the final attestation exam are awarded the Certificate of Basic Secondary Education (Svidetel’stvo ob okonchanii osnovnoy shkoly).

Since the 2011/12 school year, at the end of grade 9, some basic secondary students have also had to sit for a standardized, national competency assessment, the External Assessments of Student Achievement (EASA),8 [151] administered at a sample of schools throughout the country. The EASA tests students in Kazakh and three other subjects selected by MESRK. While EASA results have no impact on students’ academic progression, they are used by the Committee for Control in the Field of Education and Science (CCFES), a MESRK board, to compare the quality of teaching at different schools, to assess aggregate learning outcomes, and to monitor the country’s progress toward achieving its education goals. In 2015 [152], the EASA was introduced at the end of grade 4; in 2017, it was expanded to grade 11.

Upper Secondary Education

After completing basic secondary education, usually at around age 15, students are able to choose between two different streams: academic, also referred to simply as general secondary, and vocational. In 2017, around 60 percent of students at the upper secondary level were enrolled in the academic stream and 40 percent in the vocational stream, according to the 2018 OECD Education Policy Outlook [103] mentioned above. All students electing to pursue general secondary education are automatically enrolled in the first two years of senior secondary education, grades 10 and 11 in the old system and grades 11 and 12 in the new 12-year system.

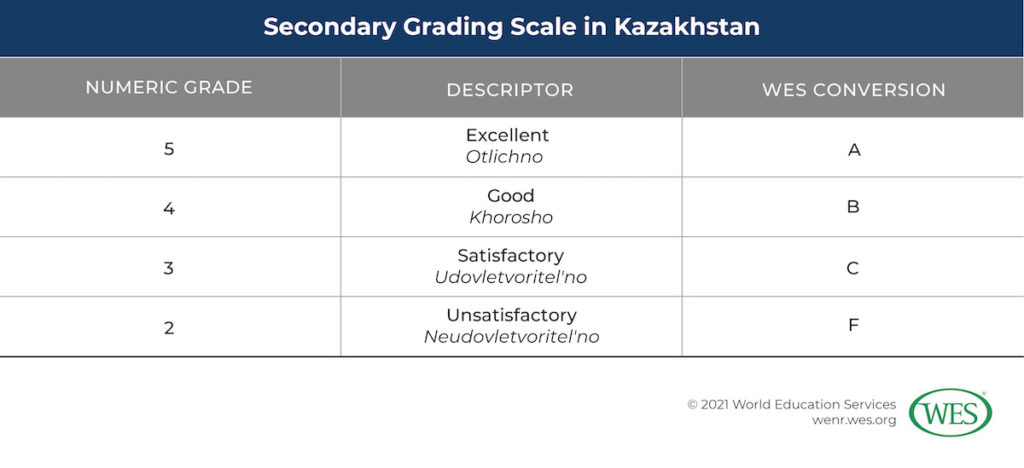

Compulsory general secondary education subjects are algebra and the beginning of analysis, biology, chemistry, geography, geometry, the history of Kazakhstan, human society and the fundamentals of law, information technology, Kazakh or Russian language and literature, a foreign language (typically English), physics, and world history. Students in upper secondary education study a maximum of 39 hours per week. They are graded on a five-point scale, with 3 representing the minimum passing grade and 5, the highest.

Since 2017, students completing the final year of upper secondary education sit for a final attestation [154], or final certification, examination that tests four mandatory subjects (algebra and the beginning of analysis, the history of Kazakhstan, Kazakh or Russian language, and native language and literature) and one elective subject. Students passing their courses and the examination are awarded the Certificate of General Secondary Education (Attestat o obshchem srednem obrazovanii).

Students hoping to enroll in higher education programs can also sit for the Unified National Test (UNT), discussed in more detail below. Prior to 2017, the UNT played a far more important role in the country’s education system, functioning as both a university entrance examination and an upper secondary school-leaving examination, although students opting not to take the UNT were still able to graduate. Results from the UNT were also used by MESRK to rank teachers, schools, and regions. The practice has since been abandoned because of criticism that it could lead to unfair comparisons.

School Infrastructure and Facilities

Most Kazakhstani students are enrolled in general day schools which teach all grades, from elementary to upper secondary. New schools must be licensed before they can begin teaching and must undergo inspection, a process known as attestation, every five years. Both the licensing and attestation process are managed by MESRK.

Despite near universal enrollment, school facilities in much of the country remain inadequate. In heavily populated urban areas, schools commonly operate in multiple shifts, with students in certain grades attending in the morning, and those in other grades, in the evening. In the 2009/10 school year, two-thirds of all schools [155] operated in two or more shifts. The SPED 2011-2020 indicated that there were even 70 three-shift schools and one that had four shifts. Multiple-shift schools must often shorten teaching hours, making it difficult for them to meet the minimum instructional hours set by MESRK.

On the other hand, in rural areas, classes are at times so small that the government has authorized multi-grade teaching. These small rural schools, known as small-class or ungraded schools, are often plagued by teacher shortages and decaying infrastructure. The OECD’s 2018 policy outlook notes that 42 percent of public schools were small-class, catering to just 8 percent of all students.

These school and teacher shortages may partly explain Kazakhstan’s poor performance in PISA assessments [156]. On the 2018 PISA [157], Kazakhstani students scored well below the OECD average in all three subjects: reading, mathematics, and science. Perhaps even more concerning, Kazakhstan’s 2018 scores in every subject declined from those achieved during previous PISA cycles. Given this decline, it seems unlikely that the disparities in learning outcomes revealed by the results of previous PISA tests were reversed. A 2015 OECD Review of School Resources in Kazakhstan [155] noted that 2012 PISA data revealed that “the language of instruction in schools (Kazakh or Russian), school location (urban or rural), and the socio-economic background of students and schools make a difference in students’ performance.”

Nazarbayev Intellectual Schools (NIS) and Nazarbayev University

Kazakhstan also maintains a network of highly competitive, state-funded learning institutions known as Nazarbayev Intellectual Schools [158] (NIS). In the words of their eponymous founder [159], Kazakhstan’s first president, Nursultan Nazarbayev, the aim of NIS is to prepare “the next generation of global-minded leaders in Kazakhstan” to fill key roles in the country’s government and major corporations, and to function as “platforms for testing and development of up-to-date academic programs.”

Since the first NIS opened in Astana in 2008, their numbers have grown steadily. There are currently 20 NIS [160] operating in all 14 oblyslar. NIS teach all grades of the 12-year elementary and secondary education cycle. Instruction is conducted in all three of the languages promoted in the government’s trilingual policy—Kazakh, Russian, and English—although upper secondary education is delivered entirely in English.

Although NIS follow the same State Curriculum Standards as all other Kazakhstani schools, their facilities, funding levels, and teacher qualifications are all far superior. NIS also have far more flexibility to innovate and adapt to student needs. Although their funding is ultimately provided by the government, NIS operate autonomously [161], free from government interference. In theory, this arrangement allows them to pilot the most modern education methods and programs, the most successful of which will then be rolled out nationwide.

In 2010, President Nazarbayev launched a similar initiative at the higher education level. Nazarbayev University [162] is a publicly funded research institution intended to be a “leading model of higher education [163], which would establish a benchmark for all higher education institutions of the country.” Also governed independently of the state, Nazarbayev University has been granted an exceptional degree of academic freedom, allowing it to develop education programs on its own and to experiment with the latest teaching and research methods. The university is also intended to be a model of internationalization, partnering with leading universities and attracting top scholars from around the globe.

But both NIS and Nazarbayev University have been criticized for exacerbating educational and socioeconomic inequality. Commentators have warned that the establishment of NIS may eventually result in the creation of two, unequal streams of education [165], with the bulk of the country’s students unable to access the high-quality education NIS provide. Others have criticized them for drawing a disproportionate share of overall government spending on education, funds that could be used more efficiently to improve the entire education system if spread more broadly. A 2017 OECD review [166] of Kazakhstan’s higher education system notes that: “Nazarbayev University is consuming a large portion of total public spending. At best, this is an experiment that carries substantial risks: it is an open question whether any excellence that the university may achieve can outweigh reduced funding for the rest of the system, and whether this excellence can be shared in a way that benefits the entire system of higher education.”

Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET)

The government of Kazakhstan views technical and vocational education and training (TVET), often known in Kazakhstan as technical and professional education (TPE), as an important means of meeting the country’s development goals. The SPED 2011-2020 identified the modernization of the country’s TVET system “in accordance with the demands of society and industrial-innovative development of economy, integration into the global educational space” as a priority. Other government plans, including MESRK’s Action Plan [167] for 2014 to 2016, have sought to expand the network of TVET institutions nationwide, to improve TVET teacher training, and to promote industry partnerships.

TVET in Kazakhstan is administered [168] by the Technical and Vocational Education Department of MESRK. The department is responsible for overall planning and monitoring of the sector, as well as the management of industry partnerships and teacher training.

Vocational Secondary Education

After completing basic secondary education, students can choose to enter either the general academic stream or the vocational stream. Students choosing the vocational stream enroll in specialized TVET colleges, which often offer both secondary and post-secondary TVET qualifications. There are currently more than 750 technical and professional colleges [169] in Kazakhstan, 58 percent of which are public; the rest are private. As mentioned above, around 40 percent of all upper secondary students are enrolled in the technical and vocational stream.

Vocational secondary education programs are typically longer than general secondary education programs, lasting from three to four years. After completing the required coursework and training, students sit for a vocational examination or submit a graduation project, after which successful students are awarded a Diploma of Vocational Secondary Education, sometimes also translated as Diploma of Technical and Professional Education. Although designed to prepare graduates for work as qualified technical and service professionals, students earning a TVET diploma can also progress to a post-secondary TVET program or a general academic higher education program. Those hoping to enroll in a higher education institution sit for the Complex Test of Applicants (CTA), a university entrance examination that differs from the Unified National Test (UNT) taken by general secondary school graduates.

TVET programs are offered in more than 150 professions in fields such as agriculture, business, construction, education, health care, and industry, among others. As at other levels of the education system, MESRK controls the content and methodology of all TVET training programs, developing State Compulsory Standards that define the subjects and curricula that can be taught throughout the country. Programs typically contain a mix of practical, on-the-job training and theoretical coursework. Curricula are modular, allowing students to complete independent units in any order, and are intended to prepare students with the skills needed to enter the labor market.

Post-secondary Vocational Education

Students can also be admitted to post-secondary technical and vocational programs after completing general or vocational upper secondary school. These post-secondary TVET programs typically last between two and three years.

Like the vocational secondary stream, post-secondary TVET programs are quite popular. According to data cited in the 2014 OECD review of secondary education in Kazakhstan [170], 45 percent of all students entering post-secondary institutions enrolled in technical and vocational programs in 2011.

After passing the required courses and training, students passing a vocational examination or completing a graduation project are awarded a vocational diploma. As with some vocational upper secondary diplomas, these post-secondary diplomas are typically translated into English as a Diploma of Technical and Professional Education [171]. Students earning a post-secondary vocational diploma often enter the workforce or enroll in general academic higher education institutions.

Higher Education

Kazakhstan’s higher education system has changed dramatically since independence. In an attempt to create a higher education system able to meet the demands of the country’s emerging market economy, policymakers have progressively reduced the government’s role in financing and supervising the sector, adopting reforms that would more closely align the system with international standards. Their success has been mixed. At times, reforms have moved too quickly or gone too far, exacerbating the problems they were meant to solve; while at others, change has moved too slowly, with government reformers finding the Soviet legacy hard to throw off.

Higher education in Kazakhstan has its beginnings in the 1920s, shortly after the country was incorporated into the Soviet Union as an autonomous republic. In the seven decades that followed, educational authorities developed a higher education system aimed primarily at developing technically competent specialists [172] to help the Soviet Union meet its economic, political, and cultural objectives. In contrast to the research universities prevalent in the West, universities throughout the Soviet Union focused almost exclusively on teaching. Most basic and applied research was conducted outside of universities in specialized institutes or academies, many of which were located outside of Kazakhstan itself.

Control over higher education during the Soviet era was also tightly centralized, allowing government planners in Moscow or Alma-Ata, as Almaty was known prior to 1993, to determine the subjects offered and the number of seats available in accordance with Soviet or republican objectives. In the Kazakh SSR, most higher education institutions were narrowly focused on either engineering, to support the oil and gas industry, or pedagogy, to achieve the Soviet Union’s goal of universal literacy. Graduates of these institutions received state diplomas that guaranteed them employment in government ministries or state-owned enterprises.

Although the Soviet Union developed a solid network of institutions—55 by independence—demand for university seats in the Kazakh SSR still far exceeded supply. In 1989, there were 226 applicants [172] for every 100 university seats. Access to higher education was especially limited for much of the country’s large rural population. Soviet-era universities in the Kazakh SSR were almost universally established in urban centers or in resource-rich regions.

Independence brought disruption. With its revenue falling, the government passed [173] the Law on Higher Education in 1993, which for the first time legalized the establishment of private universities. It also altered funding and ownership regulations for public universities. The government introduced tuition fees at previously free public universities and sold shares in a handful of them to private investors. This drive to privatize the funding and ownership of higher education institutions represented a significant departure from the Soviet era when the government was almost completely responsible for funding and administration.

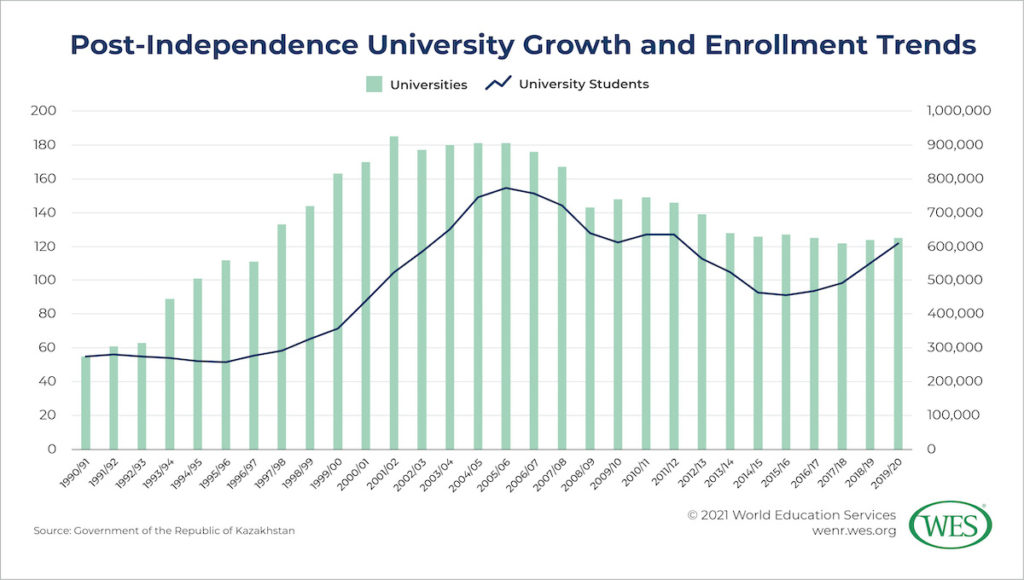

These changes led to a rapid proliferation of private higher education institutions. Over the next decade, the number of universities more than tripled, peaking at more than 180 in 2001 [174], with nearly all of the growth driven by private institutions. Enrollment took slightly longer to increase, remaining largely stagnant until the late 1990s. However, as the economy started to heat up around the start of the new millennium, young Kazakhstanis began to flood into universities. By the 2005/06 academic year, around 775,000 students were enrolled in higher education institutions, more than double the number a decade earlier.

Higher Education in Transition: Quality, Governance, and Internalization Reforms

The rapid rise in the number of private higher education institutions was not accompanied by a similar increase in the funding for or rigor of oversight and quality assurance mechanisms. As a result, education quality in many of the country’s universities deteriorated sharply, while incidences of corruption and academic fraud rose rapidly. Bribes from private and public university administrators [176] reportedly helped sway the decisions of ministry officials responsible for licensing and attesting higher education institutions; prospective students also used bribes to influence university admissions officers. Deception even spread to labs and lecture halls, where cheating was reportedly rampant. The SPED 2011-2020 noted that “Corruption has been a serious latent factor encompassing the entire system of higher education in Kazakhstan.”

With the booming economy placing the country’s public finances on a more solid footing, these challenges prompted the government to introduce expansive reforms aimed at improving and modernizing the country’s higher education system. To address concerns about corruption, the government introduced standardized national university entrance examinations, and for university freshmen, mandatory classes [177] designed to deter cheating.

The government also tightened quality assurance and accreditation processes. Beginning in the early 2000s, it began introducing stricter higher education licensing regulations and rolling out a system of voluntary accreditation. In 2006, it explicitly introduced an “optimization policy” aimed at improving the overall quality of the higher education system by strictly monitoring quality standards and forcing low-performing institutions to merge or close.

So far, the latter policy has proved effective. From 2005 to 2020, the number of universities in Kazakhstan declined by nearly a third, falling from more than 180 to 125—33 public and 92 private [135], according to government statistics. The government hopes that improved oversight and quality standards will eventually reduce that number to 100.

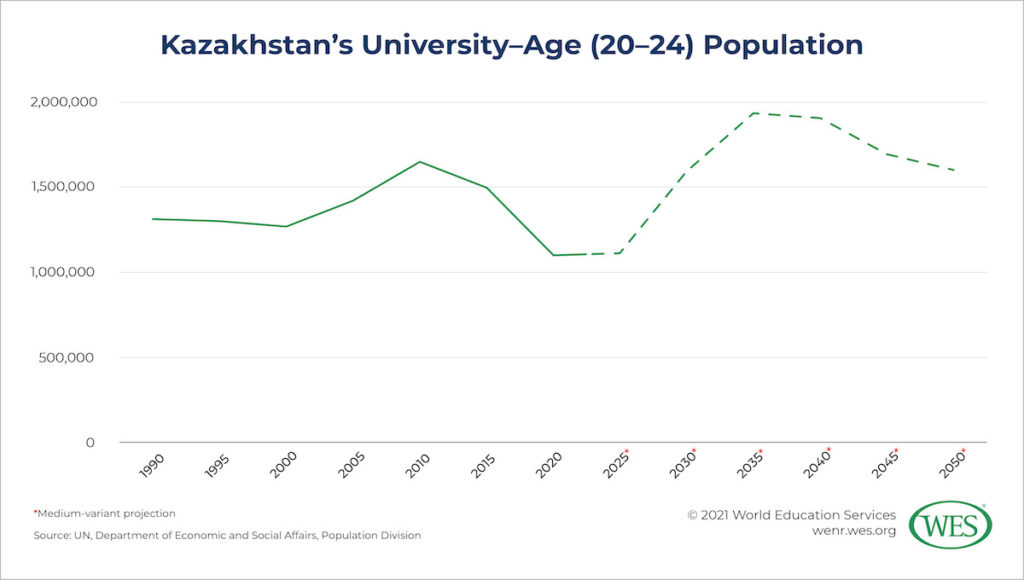

Perhaps also driving the shuttering of institutions, which today are largely financed by student tuition fees, was declining demand for higher education. The number of Kazakhstanis between the ages of 20 and 24 fell by a third between 2010 and 2020, from more than 1.6 million [34] in 2010 to 1.1 million in 2020. As a result, university enrollment has also declined, falling by more than 40 percent from its peak in 2005/06 to around 460,000 in 2015/16. Although numbers have since stabilized, policymakers expect university enrollment to decline or remain stagnant until 2025 [178].

The government has also embarked on other significant reforms, most notably those aimed at aligning the country’s higher education system with international standards. In 2010, Kazakhstan became the 47th signatory of the Bologna Process and the first Central Asian nation to join the European Higher Education Area (EHEA). Its long-planned accession—Kazakhstan signed the Lisbon Recognition Convention in 1999—was accompanied by significant changes to the country’s higher education system, including the restructuring of its qualification and credit system, the introduction of external accreditation agencies, and a gradual expansion of institutional autonomy.