Deep-rooted challenges plague Morocco’s education system. While access to formal schooling has expanded significantly, if unevenly, over the past few decades, learning outcomes remain stubbornly poor. Although nearly every Moroccan child enrolls in elementary school today, just one-third [2] reach the minimum proficiency level in reading by the time they leave. These challenges persist despite high levels of public funding. In 2021, 16.9 percent [3] of all government spending went towards education, well above world (14.8 percent) and OECD (12.4 percent) averages.

The education system’s underperformance has long perplexed Moroccan policymakers. Since the 1990s, the country has embarked on a series of ambitious reforms, each accompanied by a sense of urgency and enthusiasm, but often ending in disappointment and disillusionment.

Although these reforms attempt to address many of the challenges confronting the country’s education system, many experts1 [5] believe that they ignore a far more fundamental issue: Morocco’s complex linguistic heritage.

The Moroccan Mosaic

The demographic composition of the Kingdom of Morocco, known in Arabic as Al-Maghreb, or ‘the West,’ differs significantly from much of the rest of the Arab world. The country’s population is divided into two large ethnic groups: Arabs and Imazighen (singular: Amazigh), more commonly known as Berbers. The latter trace their lineage back to the pre-Arab inhabitants of North Africa. While estimates vary, Imazighen may make up as much as half [6] of the 37.1 million people [7] in Morocco.

Although united by religion—nearly 99 percent [8] of all Moroccans are Sunni Muslims—Arabs and Imazighen often differ in cultural practices, occupation, and language. While Arab Moroccans grow up speaking darija, the vernacular Arabic spoken in Morocco, most Imazighen grow up speaking one of a variety of Amazigh languages, which are known collectively as Tamazight [9]. Although Moroccan policymakers long treated Tamazight with indifference, and, at times, contempt, in recent decades, they’ve approached the language with a more conciliatory attitude. In 2011, Morocco’s newly adopted constitution finally recognized Tamazight as one of the country’s two official languages.

But the new constitution did not change the status of darija, the country’s most widely understood language. Although spoken by more than 90 percent [10] of all Moroccans—both Arab and Amazigh—darija is not officially recognized in Morocco. Besides Tamazight, the country’s only other official language is Modern Standard Arabic (MSA). MSA is a closely related variant of classical, Quranic Arabic, which was the traditional language of religion and high culture in much of the Arab world. Although darija is related to MSA, it differs far more than the other major Arabic dialects spoken around the world, sharing only a limited degree of mutual intelligibility [11] with standard Arabic.

The legacy of European colonialism further complicates the linguistic identity of Morocco’s population. Although comparatively short-lived, the protectorate established by France over most of Morocco between 1912 and 1956 has had a long-lasting effect. Even today, French remains the language of elite communication, and fluency in French is required to access and succeed in major private enterprises and elite scientific disciplines.

In northern Morocco, where authorities from Madrid once administered a far smaller protectorate, Spanish is also still taught in some schools, although its use outside the classroom is limited. On the other hand, English is rapidly growing in prominence. Across Morocco, English is showing up more and more in business, entertainment, and the education system.

While Morocco’s people have managed to blend these Arab, Amazigh, and European influences into a rich cultural tapestry, the country’s schools and universities have been less successful. Since independence in 1956, language policy in Morocco has proved contentious, especially in education.

Early in the post-independence period, government officials recognized Arabization, or the adoption of Arabic in the place of French, as a top priority for the education system. But implementation was slow at first, in part because of a shortage of qualified Arabic-speaking teachers. The colonial education system established by the French largely excluded native-born Moroccans, preparing few with the skills needed to educate the first generations of independent Moroccans. At independence, Moroccan university graduates numbered just 640, and the country’s illiteracy rate stood at roughly 80 percent.2 [12] As a result, Moroccan schools were forced to rely heavily on teachers from France and other North African countries for decades after independence.

Still, for years, Morocco made slow, carefully planned progress toward its goal of Arabizing the education system, with Arabic gradually introduced [13] into the classroom alongside French. But that cautious approach was abandoned in the 1980s, when the education ministry hastily replaced French with Arabic for most students and subjects over the course of just a few years. This ill-planned implementation had a devastating impact on the education of a generation of students. Elementary enrollment [14], which had been rising steadily for decades, fell almost immediately, only recovering again in the 1990s.

Experts today still question the wisdom of this Arabization policy—at least in the form it finally took in Morocco. The variety of Arabic that ultimately replaced French in the country’s schools was not darija, the vernacular spoken by most Moroccans, but MSA. As noted previously, MSA has limited mutual intelligibility with darija. Its use in learning materials for nearly all subjects in public schools, beginning in preschool, forces students to learn how to read and write in an almost unintelligible language. On the other hand, darija, although spoken informally in the classroom, is never taught as a formal subject.

Many experts believe that MSA’s prominence in Morocco’s education system accounts for the country’s shockingly high rates of illiteracy. Almost two-thirds (64 percent) of Moroccan fourth graders failed to meet the lowest international benchmark of reading achievement on the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) 2016 [15], against an international median of just 4 percent. None reached the advanced benchmark.

But nearly as important is what, and whom, the Arabization process left unaffected. Arabization was only applied at public schools and in certain academic fields. It did not apply to private institutions or public university science and technology disciplines. In these, French remained in place.

This development has had serious implications for Moroccan society. Experts contend that it has helped create two classes of Moroccans, divided by knowledge of French. Private schools and the lycées de mission, elite international schools certified by the Agency for French Education Abroad [16] and administered by the French foreign ministry, teach almost entirely in French, allowing their students to attain a high degree of mastery over the language. But their impact reaches only a privileged few. A 2008 study which found that, since independence, 200 families have accounted for 45 percent of all lycées de mission graduates, with 20 families alone accounting for 15 percent.3 [17]

Meanwhile, although French as a foreign language is introduced as a subject in public schools in grade 3, attaining fluency from these courses alone is nearly impossible. Pierre Vermeren, a French historian, noted in 2002 that “It is quite impossible for most students in Morocco to be truly fluent in French and Arabic if they attend ordinary state schools. For such students there is practically no possibility to succeed at university, since all the scientific disciplines and medicine are taught exclusively in French.”4 [18]

This makes it difficult for most Moroccans educated in the public schools to access the highest echelons of Moroccan society. Lacking adequate language skills, they often struggle to access and succeed in the most selective public university science and technology programs, which are still taught in French. They face similar challenges applying to and thriving in private universities at home or in public universities in France, both of which are popular options for the many applicants rejected by the most prestigious Moroccan public university faculties.

The impact of this situation extends far beyond the classroom. Graduates of non-selective university faculties, the destination of most university-bound public secondary school students, face significantly grimmer employment prospects than their counterparts graduating from more selective public faculties or from private and international universities. Unemployment rates for graduates of non-selective public university faculties are extremely high, reaching 18.7 percent [19] four years after graduation in 2018. That same year, just 8.5 percent of graduates from selective public faculties and 5.6 percent of graduates from private higher education institutions were jobless.

Morocco’s current youth bulge makes addressing these challenges even more pressing. In 2022, Moroccans under the age of 24 made up 41 percent [20] of the country’s population. These numbers are expected to peak [21] by the end of this decade.

Unfortunately, many struggle to find a decent job at home. About 29 percent [22] of 15- to 24-year-olds in Morocco are NEETs—not in education, employment, or training. This is driving many of them overseas. According to a 2019 Arab Barometer [23] survey, 70 percent of all Moroccans between the ages of 18 and 29 had thought about leaving the country. Among all surveyed Moroccans, half considered emigrating for economic reasons, another 15 percent for educational opportunities.

Although the reasons for their malaise are complex, the state of the education system likely plays a role. Revealingly, desire to emigrate tends to rise with education level. While just 24 percent of Moroccans with only an elementary education had thought of emigrating, more than half of those with a secondary (64 percent) and higher (60 percent) education had thought the same. Unsurprisingly, a 2021 Arab Barometer [23] survey found that just 45 percent of all Moroccans were satisfied with their country’s education system.

To address these challenges, Moroccan policymakers have introduced major changes in recent years, discussed in more detail below, at all levels of the education system. Whether these reforms—which notably make no mention of darija—can meaningfully improve the quality of education for all Moroccans remains to be seen.

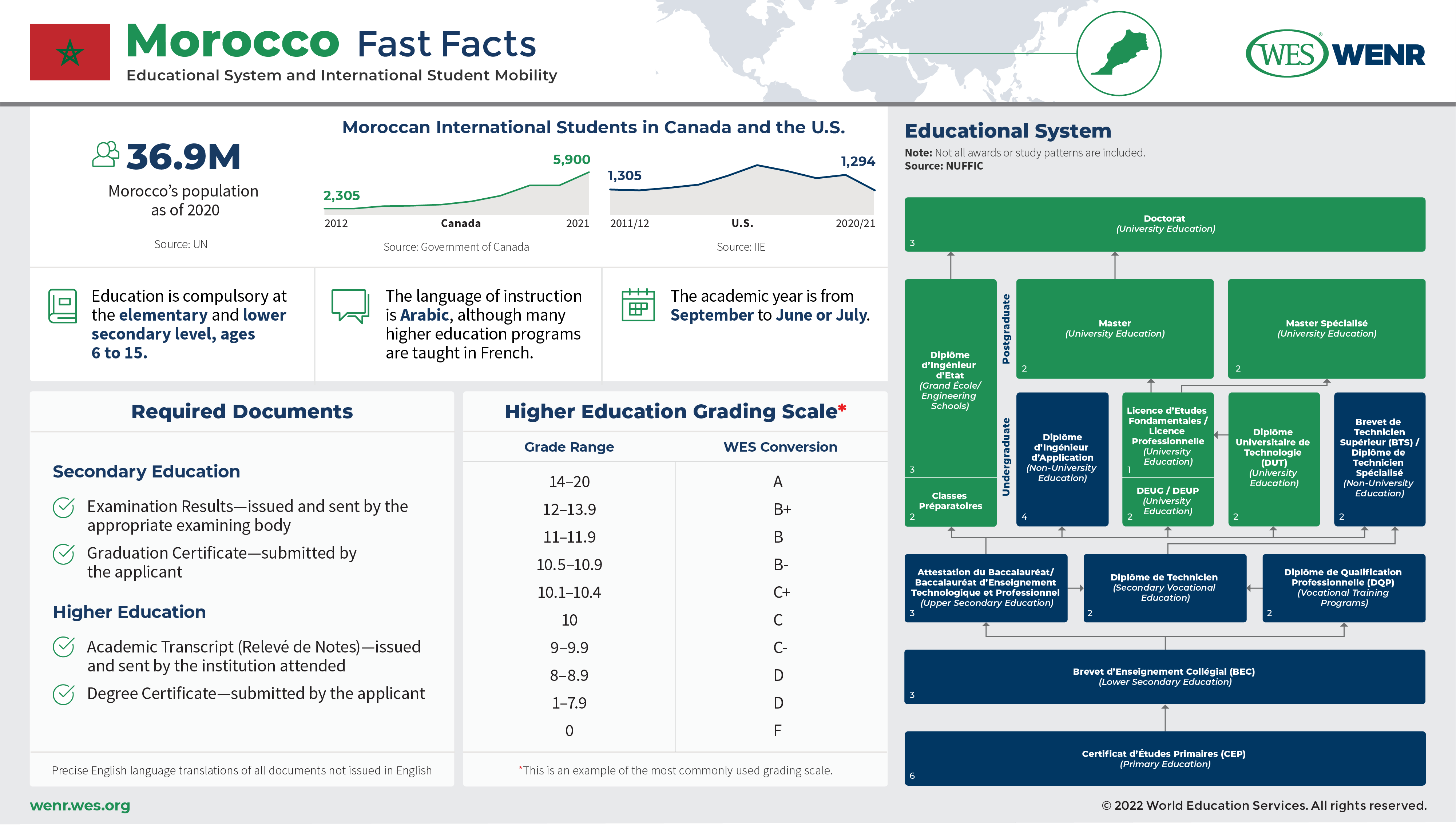

Outbound Student Mobility

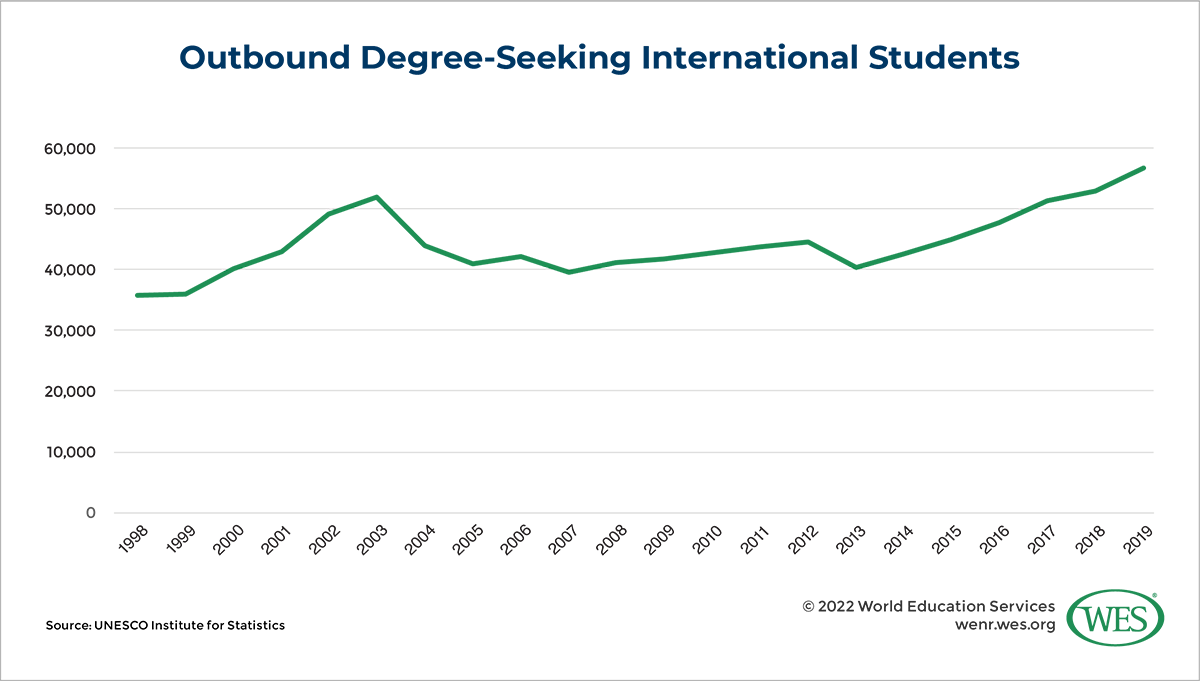

Despite free and, in many disciplines, guaranteed seats at public universities, the challenges outlined above make an overseas education attractive to many Moroccans. As a result, Morocco is a major source of globally mobile students. According to data from the UNESCO Institute of Statistics [24] (UIS), 56,758 Moroccan students studied internationally in 2019, the second highest in all of Africa, trailing only Nigeria (69,106).

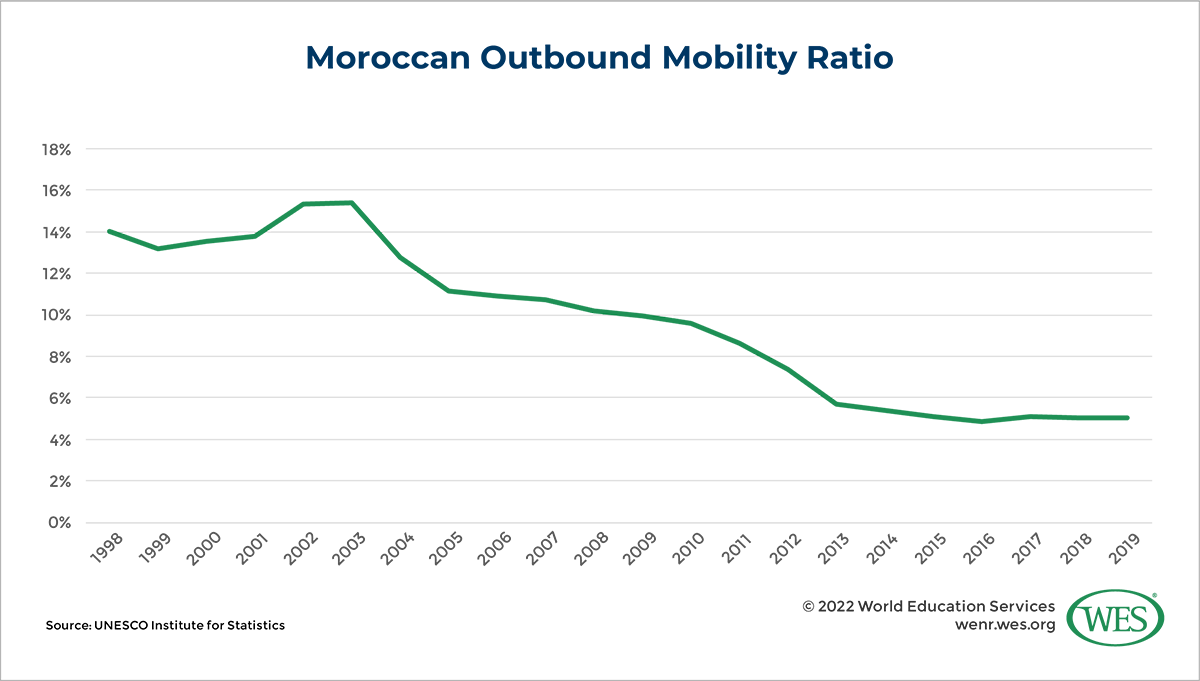

While that number has trended upwards steadily in recent years—since 2013, the number of Moroccans studying abroad has increased by 41 percent—young Moroccans have long been more likely to study overseas than their peers elsewhere around the world. Today, Moroccans studying overseas amount to 5.1 percent [26] of the number enrolled in tertiary education programs in Morocco, compared with 4.8 percent and 2.4 percent in sub-Saharan Africa and North Africa, respectively.

That percentage was even higher in the past. In 2003, Morocco’s outbound mobility ratio [26] peaked at 15.4 percent, compared witht6.8 percent, 2.7 percent, and 2.1 percent in sub-Saharan Africa, North Africa, and the world, respectively. That same year, 51,838 Moroccans, or more than 90 percent of the number today, were enrolled overseas. While overseas enrollment declined sharply in the wake of the 2004 Madrid train bombings [27], in which a number of Moroccans were implicated, it quickly stabilized, hovering at around 40,000 annually until the 2013 upswing.

Although Morocco’s outbound mobility ratio has declined since the early 2000s, many of the factors driving students to study abroad remain the same. Among the most important is the poor reputation of Morocco’s higher education institutions, which are often overcrowded and underfinanced, and offer few employment prospects to their graduates. The situation is especially bad at the country’s public universities, which enroll more than 90 percent [29] of all university students. As a result of these challenges, Moroccan employers are reported [30] to prefer hiring job seekers educated abroad or at one of a small number of Moroccan private universities, rather than hiring those educated at public universities.

Top Destination Countries

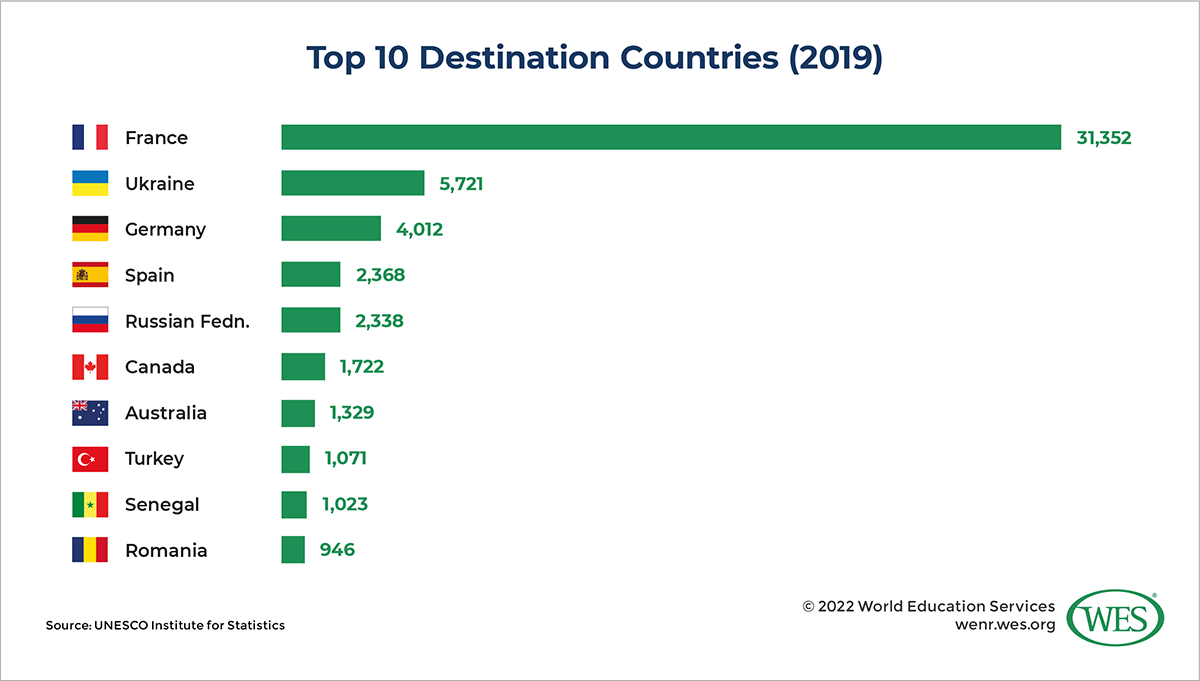

Most Moroccan international students head to Europe, drawn by the continent’s geographical proximity and the close social, political, and economic links that have long tied the southern and northern shores of the Mediterranean together.

Interested in ensuring stability in their closest African neighbor, European policymakers have long taken an interest in promoting Morocco’s economic development. Although the policies they’ve adopted to promote that development do not always have the intended effect, some have helped facilitate university enrollment. The European Union has included Morocco in a number of funded student mobility programs, such as Erasmus+ [31] and Tempus [32].

France

Since about 1900, no European country has been more closely associated with Morocco than France. Today, France is Morocco’s largest trading partner [34] and the home of Morocco’s largest diaspora community [35]. Unsurprisingly, it is also the destination of most Moroccan international students. In 2019, 31,352 Moroccan degree-seeking students, or around 55 percent of all Moroccan international students that year, were enrolled in French higher education institutions. Moroccan students are the single largest group [36] of international students in France today.

Cost considerations may play some role in encouraging Moroccans to study in France. Although higher than at Moroccan universities, tuition fees at French universities, which are subsidized by the government [37], are lower [38] than in most other major destination countries, even after recent changes [39] raised fees. The French government also provides generous scholarships and grants [40] to Moroccan students studying in France.

But France’s colonial legacy—as well as the French government’s ongoing attempts to maintain some control in its former African colonies, arrangements known as Françafrique—likely explains much of this mobility. Around 35 percent [41] of Morocco’s population still speaks French today, a result of the privileging of French by colonial authorities in public administration, education, and the media. Public agencies and private organizations headquartered in France also maintain an extensive network of French schools and universities [42] in the country, some of which were established [43] during the French protectorate in Morocco. The passing of a controversial law [44] in 2019 requiring that certain scientific and technical subjects be taught in French at middle and high schools will eventually also better prepare students for enrollment in French universities.

These ties have made France a second home for many elite Moroccans. In fact, obtaining a French degree has long been a rite of passage for Morocco’s elite, opening doors to employment at top companies [45] in Morocco and around the world.

Ukraine

Until recently, Ukraine was rapidly growing in popularity among Moroccan university students. Between 2011 and 2020, the number of Moroccan students in Ukraine grew by more than 550 percent, from 871 to 5,721. According to Ukrainian statistics [46], that growth made Morocco the second-largest source of international students in Ukraine.

Most of these Moroccans [47] enrolled in one of Ukraine’s medical universities, which over the past decade have grown into a major destination for international medical students from around the world due to their comparatively low cost and high quality [48]. Moroccans enrolling in these programs would often first complete a five- to ten-month preparatory course [49] to improve their language abilities (usually in Ukrainian or English) and brush up on the fundamentals necessary for their field of study.

Ukraine’s low cost of living and the relative ease with which Moroccans were able to obtain visas—relative to their efforts to enter other European countries, that is—also made the country attractive. Still, Moroccan students, like others from Africa [50], faced significant challenges in Ukraine, ranging from extortion and corruption [51] to racial [52] and police [53] violence.

The invasion of Ukraine in early 2022 changed this picture dramatically. As fighting spread across the country, many Moroccan and other international students raced to evacuate [54], facing along the way not only the perils of war [55], but also racism and discrimination [56]. Some of those making it to neighboring countries were able to board flights organized [57] by the Moroccan government to bring them home.

But others chose to remain in Ukraine. “If I leave Ukraine, all my five-year dreams at university will be gone,” explained [58] one student in an interview with Al-Fanar Media shortly after hostilities began. “This is my last academic year before graduation. I was about to regularize my permanent residence status in Ukraine. For me, leaving would be a grave loss.”

With the war unlikely to end anytime soon, Moroccan students choosing to remain in Ukraine face extreme danger. The conflict has already claimed the life of at least one Moroccan student [59]. Another was arrested [60] and sentenced to death by Russian authorities for his involvement with the Ukrainian military, although he has since been released in a prisoner swap.

Students forced to flee face enormous obstacles to completing their degrees, despite efforts by the Moroccan government to help. Since the invasion began, Moroccan officials have worked with other European countries [61] to find seats for displaced Moroccan students. They also launched an online platform [62] to help returned students obtain their Ukrainian academic documents.

The government also announced plans to integrate returned students into Moroccan universities. Currently, plans call for evacuated medical and engineering students to take placement tests [63], after which they will be integrated into private medical and public engineering faculties.

These plans have not been well received. Groups representing medical [64] and engineering [65] students already enrolled in Moroccan universities denounced the proposals, arguing that the returned students would further overcrowd universities and compromise educational quality. On the other side, returned medical students oppose [66] the government’s plans to reintegrate them into private faculties, concerned by the prohibitively high cost of these private institutions.

Repatriated students have also raised concerns [63] about the placement tests, arguing that the exams will unfairly penalize them for learning in a different language and studying a different curriculum. These concerns seem well-founded. When the medical placement tests were finally held in late September 2022, 70 percent [67] of the repatriated students failed.

Just 393 students sat for those exams. With the war ongoing and reintegration efforts the subject of considerable controversy, the fate of thousands of other Moroccan international students, whether still in Ukraine or back home, remains unclear.

China

China may also be a growing destination for globally mobile Moroccan students, although internationally comparable enrollment data is not readily available. As is the case elsewhere throughout Africa [68], China is extending [69] its economic, diplomatic, and cultural presence in Morocco, courted [70] by the kingdom’s drive to become the world’s Gateway to Africa. In recent years, major Chinese financial institutions have opened regional headquarters in Casablanca from which they intend to manage their affairs in various African countries.

Chinese organizations are also funding major infrastructure projects throughout Morocco. In Morocco’s north, Chinese state-owned companies have taken the lead on financing, building, and, eventually, occupying an ambitious new smart city, Mohammed VI Tangier Tech City [71], located near Tanger Med, the largest port [72] in both Africa and the Mediterranean.

On Morocco’s educational front, three Confucius Institutes [73] currently promote and teach Chinese language and culture, and plans have been made to establish a joint institute to study China’s Belt and Road Initiative. The Chinese government, as well as some of the country’s municipal authorities and universities, also offer scholarships [74] to help Moroccans finance their studies in China. While the total number of Moroccan students in China is likely limited today, given the growing connections between the two countries, future growth seems likely.

Canada and the United States

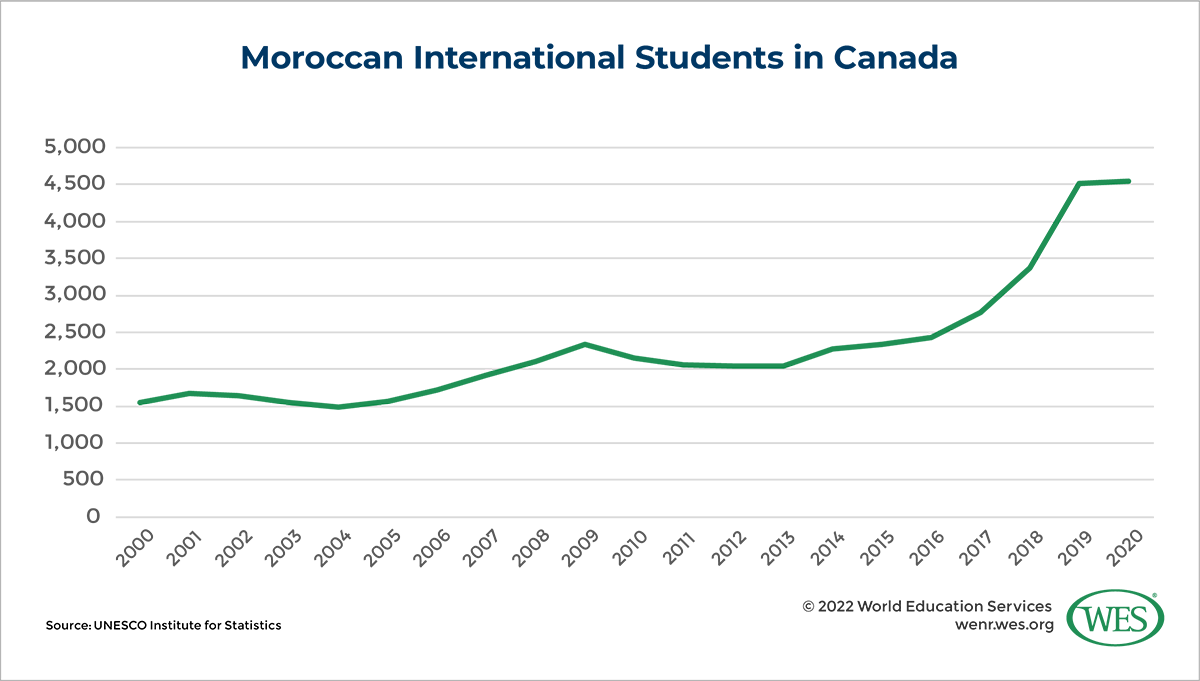

According to UIS data, outside Europe, Canada is currently the most popular country for internationally mobile Moroccan students. According to Canadian government data [75], 5,900 Moroccans held a study permit in Canada at the end of 2021, making Morocco the 16th-largest source of international students in Canada that year. Most Moroccans head to French-speaking universities located in Francophone Quebec, although government data [76] suggest that sizable numbers of study permit holders also head to New Brunswick, Canada’s only bilingual province.

Enrollment growth has been strong in recent years: Since 2016, the number of Moroccan students in Canada has increased by 87 percent. Enrollment grew 34 percent between 2018 and 2019 alone. In fact, even with the pandemic disrupting international travel—and leading to a 17 percent decline in the overall number of international study permit holders in Canada—Moroccan enrollment still increased, though marginally (0.6 percent) in 2020.

There are reasons to think these numbers could rise even more in the coming years. Some observers [78] are predicting that Canada will become an increasingly popular alternative to France, where recent tuition fee hikes and well-publicized outbursts of Islamophobia have made life for Moroccan international students difficult. Additionally, although tuition fees at Canadian colleges and universities are far higher than those of their French counterparts, some estimates [79] place the cost of living in Canada below that of France.

More important is the attitude of Canada towards Moroccan international students and immigrants, especially given the desire of many Moroccans to immigrate. According to public opinion surveys [80], residents of Morocco are among the most likely of all MENA (Middle East and North Africa) residents to want to leave their country. Young, educated Moroccans are particularly likely to want to head abroad. According to the 2019 Arab Barometer survey [23] mentioned above, more than 60 percent of those with a secondary or university degree and 70 percent of those between the ages of 18 and 29 had considered emigrating.

Although most Moroccan migrants still head to Europe, sizable numbers of highly educated Moroccans [81] have long made their way across the Atlantic to Canada and the United States. In fact, recent studies [82] reveal that Canada is the most popular migration destination among young, highly educated Moroccans. As of 2019, there were more than 74,000 Moroccan immigrants [83] living in Canada.

Canadian immigration policies could attract even more. For years, the Canadian government has made attracting immigrants a priority to offset its aging population and low birthrate. The country’s latest Immigration Levels Plan [84] sets a goal of welcoming more than 1.3 million new immigrants between 2022 and 2024 alone. The country has also recently made attracting French-speaking immigrants a priority. In 2019, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) released the Francophone Immigration Strategy [85], which seeks to increase Francophone immigration in provinces and territories throughout the country.

Canada’s attitude toward international students also bodes well for Morocco. For graduating international students, the country offers comparatively generous pathways to employment which, as part of its Francophone Immigration Strategy, it hopes to promote heavily among French-speaking international students. Its current International Education Strategy [86] also highlights the importance of diversifying the countries from which Canada welcomes international students, explicitly identifying Morocco as a priority country. In 2019, IRCC also added Morocco [87], alongside French-speaking Senegal, to the list of countries whose residents are eligible for the Student Direct Stream (SDS), an expedited study permit processing program.

Moroccan Migration Trends

Since the middle of the twentieth century, Morocco has been a major source of international migrants. Moroccan immigration [88] to Europe picked up, following the outbreak of the Algerian War of Independence in 1954, which abruptly halted French recruitment of Algerian workers. It accelerated even faster over the next decade, as Europe’s economic growth drove demand for low-income labor.

Initially, most Moroccans made their way to France, the Netherlands, Belgium, and, to a lesser extent, Germany. But following the accession of Spain and Italy to the European Communities in 1986, both countries have attracted large numbers of Moroccans. In recent decades, the U.S. and Canada, particularly the French-speaking province of Quebec, have also welcomed increasing numbers of highly educated Moroccans.

While much of this migration was initially intended to be temporary, it has become more and more permanent over time, and there are sizable Moroccan communities in these countries. In 2020, 3.25 million Moroccans lived abroad, the second-highest number among all African countries [89], trailing only Egypt. According to UN data [90], in 2020, the largest number of these migrants resided in France (1.1 million), followed by Spain (785,000), Italy (450,000), Belgium (225,000), and the Netherlands (175,000). There were 76,460 and 75,009 in the U.S. and Canada, respectively. Remittances from overseas Moroccans make up more than 5 percent of the country’s GDP. Although significant, this percentage is well below that of many other large immigration countries.

More recently, Morocco has grown into a significant transmigration country, as undocumented immigrants from countries in sub-Saharan Africa cross the Sahara to Morocco. While many then attempt to enter the Spanish cities of Ceuta and Melilla, which are located on the northwest African coast and share a land border with Morocco, many also settle down in Morocco. In 2020, there were 102,358 immigrants in Morocco.

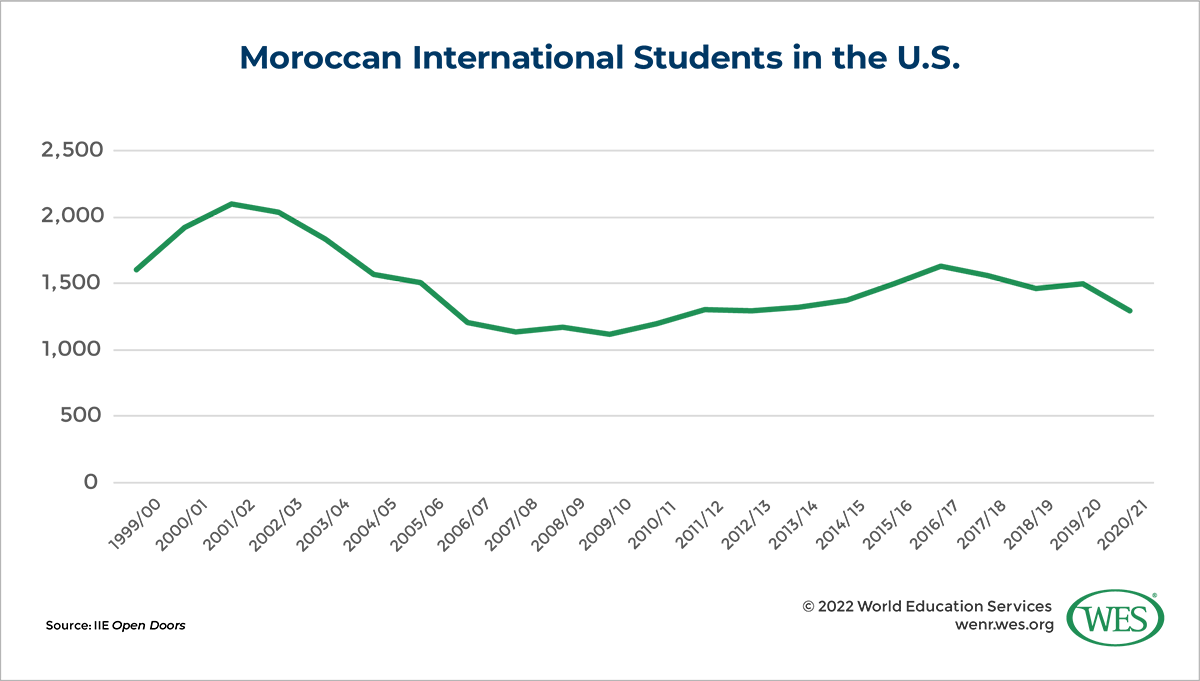

The growing flow of Moroccan students to Canada, which accelerated in 2017, may also have benefited from political developments occurring across Canada’s southern border. After years of slow but steady growth, the victory of Donald J. Trump in the 2016 U.S. presidential election marked the start of a soft downturn in Moroccan enrollment in U.S. higher education institutions. According to data from the Open Doors report [91] published by the Institute of International Education (IIE), between the 2016/17 and 2018/19 academic years, Moroccan enrollment declined by 11 percent, although it ticked up marginally the next year. Although then-president Trump’s Muslim travel bans did not target Morocco [92] specifically, his hostile attitude toward Muslim majority countries—which included a campaign call for a “total and complete shutdown [93] of Muslims entering the United States”—undoubtedly influenced the decisions of prospective Moroccan international students.

Following the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, Moroccan enrollment in the U.S. also proved far less resilient than in Canada. Between 2019/20 and 2020/21, Moroccan enrollment fell by 14 percent.

Even discounting the impact of Trump’s rhetoric and the health crisis, the total number of Moroccan students studying in the U.S. has long been limited. In fact, despite strong and growing diplomatic and commercial relations between the two countries, enrollment, even in 2019/20 before the pandemic, was 29 percent below its level in 2001/02. Observers note that Moroccans have long tended to shy away from the U.S. because of the proximity of less expensive, yet still high-quality, universities in Europe [95], and also because of significant differences between the Moroccan and U.S. educational systems.

Still, there may be reason to think that this state of affairs could be changing. Not only is Trump’s defeat in the 2020 election likely to make the U.S. a more attractive study destination for Moroccan students—public opinion surveys revealed that, pre-election, Moroccans far preferred [96] Joseph R. Biden Jr. to Trump—cultural shifts and educational reforms underway in Morocco may have the same effect.

Although French is unlikely to be supplanted as the predominant language of business and public administration in Morocco anytime soon, interest in English is high and rising among young Moroccans. A study [97] conducted by the British Council in early 2021 found that 40 percent of Moroccans between the ages of 15 and 25 believed English was the most important language to learn, compared with just 10 percent for French. Although the Moroccan government has long ruled out [98] replacing French with English at the country’s schools, it too has taken notice of the growing shift towards English.

The government has made plans to introduce English as a foreign language to children at age 12 instead of 15. It has also shown signs that it may be interested in encouraging the use of English [99] as a medium of instruction at the university level. Poor English skills—the 2021 EF English Proficiency Index [100] (EF EPI) ranks Morocco’s English proficiency as low—are often regarded as a deterrent to Moroccan enrollment in Anglophone universities.

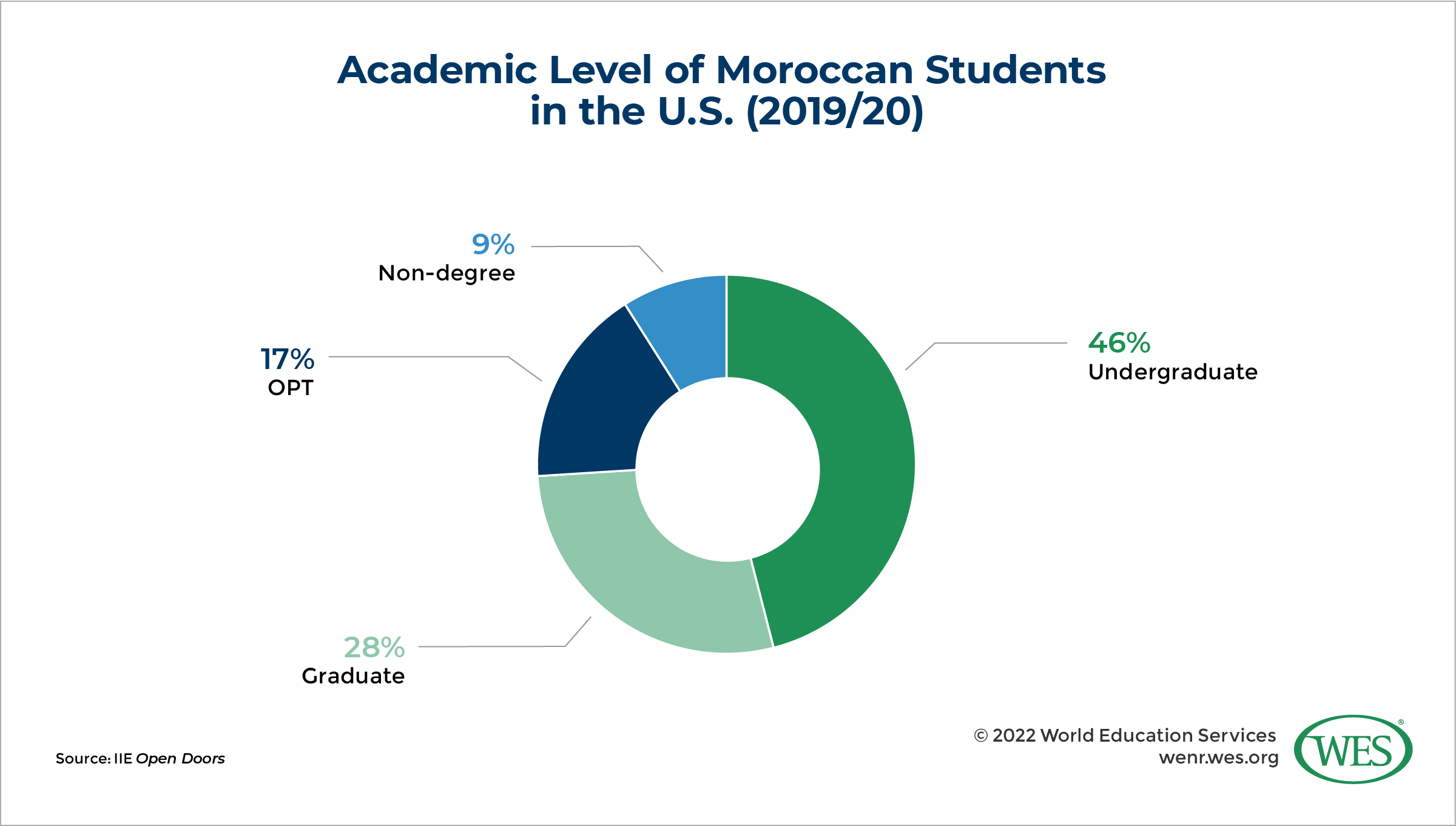

These changes are expected to require a massive retraining of the country’s teacher workforce to increase its English proficiency, which many predict will result in growing enrollment in English-medium teacher training programs at Anglophone institutions around the world. Morocco already sends a large number of teachers abroad for education and training. According to the U.S. Department of Commerce [101], during the 2019/20 academic year, 23 percent of Moroccan students in the U.S. were studying for a degree in education; 12 percent in health professions; 11 percent in business and management; 5 percent in engineering, technologies, and technical science fields; and 4 percent in humanities and social sciences.

More English language training at Moroccan universities could also boost what are currently comparatively low graduate enrollment numbers. Compared with the world average of 35 percent, just 28 percent [102] of Moroccan students in the U.S. were enrolled in graduate programs in 2019/20. Growing graduate enrollment may also boost participation in the Optional Practical Training (OPT) program—graduate students make up the majority of OPT participants—which also slightly trails world averages. In 2019/20, around 17 percent of Moroccan students in the U.S. were enrolled in the OPT program, compared with the world average of 21 percent.

Conversely, comparatively high percentages of Moroccans are enrolled at the undergraduate and non-degree levels. In 2019/20, around 46 percent of Moroccan students were pursuing undergraduate degrees, well above the world average of 39 percent. Around 9 percent were pursuing non-degree programs (compared with the world average of 5 percent), likely in order to boost their linguistic and academic skills prior to starting a degree program.

Inbound Student Mobility

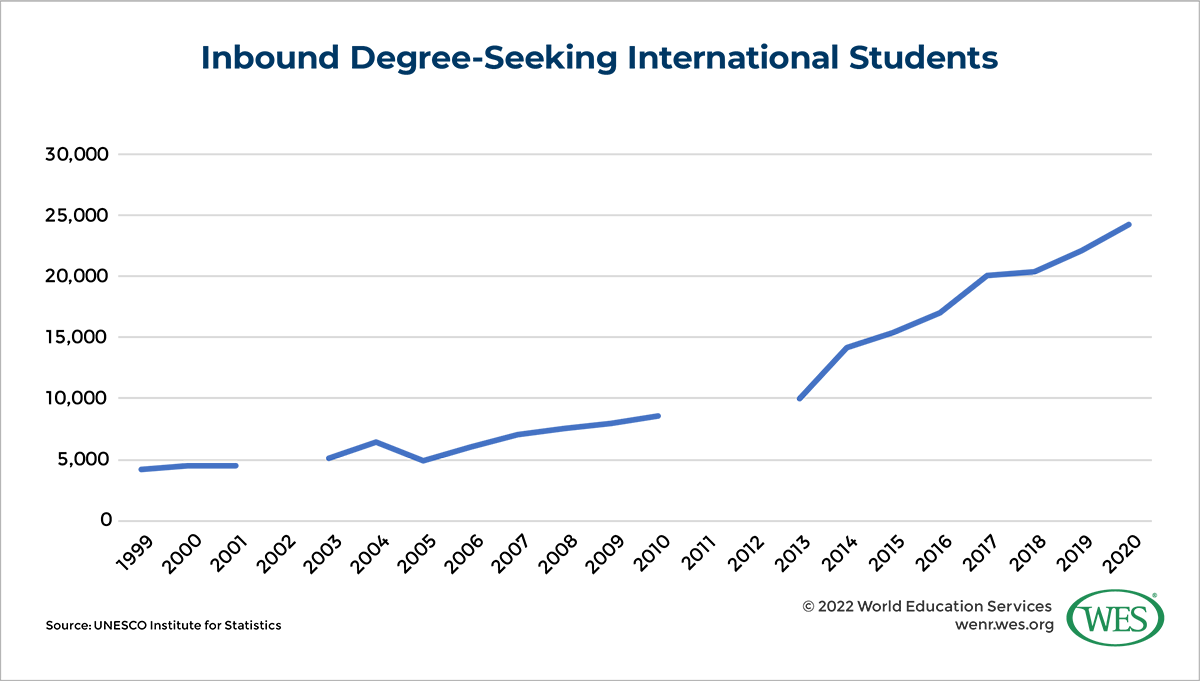

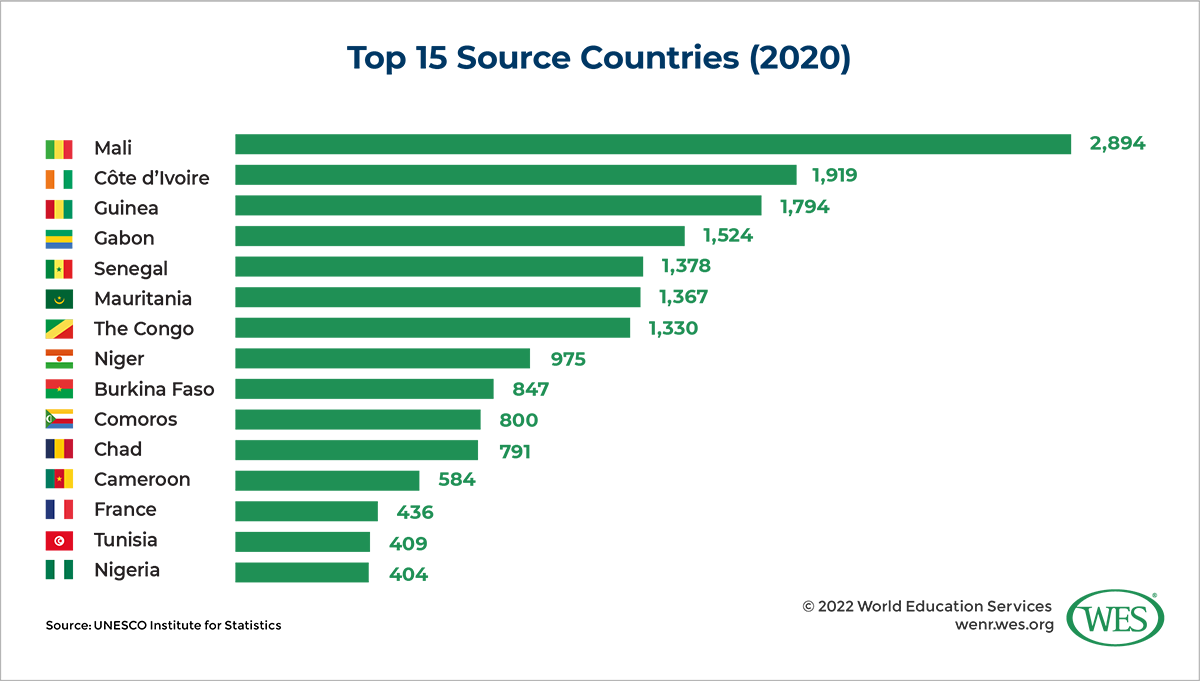

Not only is Morocco one of the largest sources of Africa’s international students, it is also one of the continent’s most popular study destinations. In 2020, Morocco hosted 24,226 students [104], the second-highest number among all African countries, trailing only the educational juggernaut South Africa [105] (40,712).

Nearly all of these students come from other African countries. In 2020, 85 percent of all international students in Morocco were from other African countries. Sub-Saharan Francophone countries in particular send large numbers of international students to Morocco. In all but one of the top 12 sources of international students in Morocco—all of which were sub-Saharan African countries, in 2020—French was an official language [107]. In the last, Mauritania, Arabic is the official language, although French is widely used throughout the country.

Morocco’s popularity as a destination for globally mobile students has grown rapidly in recent years, thanks to certain government policies. Between 2013 and 2020, inbound international student enrollment grew by 143 percent. This growth coincides with a reversal of long-standing Moroccan policy vis-à-vis sub-Saharan Africa: Over the past decade, Morocco has moved to strengthen its ties with sub-Saharan African countries. These efforts culminated in 2017, when Morocco rejoined [109] the African Union (AU) more than three decades after it had withdrawn in protest over the AU’s recognition of the independence of the Western Sahara.

This realignment aims not only to garner regional support [110] for Morocco’s annexation of the Western Sahara [111], but also to improve Morocco’s domestic economy and burnish its international image. Morocco is actively striving to position itself as the world’s Gateway to Africa—or, more specifically, the Gateway to Africa for Europe, the U.S., and China—a move it hopes will give it a central position in the trade flows to and from the world’s fastest growing market.

The government has made a similar push into sub-Saharan African countries with respect to education. Morocco’s well-regarded imam training programming [112]—which aims to combat extremism—welcomes hundreds of students from across sub-Saharan Africa each year. The government also hopes to turn its higher education sector into a regional education hub [113]. Through the Moroccan Agency for International Cooperation (AMCI), the kingdom offers [114] thousands of scholarships to predominately French-speaking students [115] from Francophone sub-Saharan Africa, 6,500 [116] in 2017 alone.

Further encouraging international students to study in Morocco, as the British Council notes [99], is the kingdom’s political stability in a volatile region, its low cost of living, its proximity to Europe, and its comfortable, Mediterranean climate. Its long history as a transmigration hub also makes it a familiar destination for many students from sub-Saharan countries.

Despite Morocco’s success in attracting these students, conditions in the country threaten to hinder its future growth as an international student destination. Observers [117] have warned that a lack of programs taught in English at Moroccan universities could make it difficult to attract more students. While Africa is home to a sizable number of French [118] and Arabic speakers—the two main languages of instruction in Moroccan universities—estimates [119] suggest that its English speakers are even more numerous.

Inadequate infrastructure—most notably a lack of on-campus student housing—and the lack of a national credit system—which complicates transferring between Moroccan and non-Moroccan institutions—are also major issues. More troubling still are long-standing reports of racism and discrimination [120] directed against students and immigrants from sub-Saharan Africa.

The Education System of Morocco

Although the legacy of France’s colonial rule looms large over Morocco’s education system today, formal learning in the Kingdom of Morocco has far deeper roots. In the mid-ninth century AD, Fatima al-Fihri, a wealthy and well-educated Arab woman, founded what would eventually become the University of al-Qarawiyyin in Fez, which some consider the world’s oldest continuously operating educational institution [121].

Today, al-Qarawiyyin is a part of Morocco’s modern university system. But for most of its existence, it was run as a madrasa, or Islamic school, offering advanced training in Islamic and scientific fields. A more general education was provided at msids, small religious schools often attached to mosques, which taught reading, writing, and arithmetic, and helped students memorize the Qur’an. Until independence, Islamic schools educated most Moroccan children.

But the seeds of Morocco’s contemporary education system were planted by the French. Following the establishment of the protectorate in 1912, French authorities built [122] a small number of schools in major cities that offered a modern curriculum taught in French.

Still, during much of the protectorate, which came to an end in 1956, these institutions enrolled few Moroccan children. In 1950, protectorate schools enrolled just 13 percent of Moroccan children. At the higher education level, numbers were far lower, and by independence, only 640 Moroccans had obtained a university degree. Unsurprisingly, at that time around 80 percent of all Moroccans were illiterate, and female illiteracy was nearly universal.5 [123]

The newly independent Moroccan government made expanding the education system one of its first priorities. The national government embarked on a massive building program, establishing schools, grandes écoles, and universities, modeled after those in France, across the country. In 1963, it made education compulsory [124] for all children between the ages of 7 and 13, nationwide. The results were impressive: By 1970, roughly 50 percent of all Moroccan children were enrolled in school.6 [125]

Education policy in these years was guided by the need to develop a class of professionals able to assume the roles of departed French civil servants. To that end, public universities provided most students with a general education aimed at preparing them for jobs in the growing national bureaucracy. With the government guaranteeing graduates a position in the civil service, a university degree helped young Moroccans rapidly climb the social ladder.

But the opportunities that a university education afforded began shrinking rapidly in the 1970s. With student protests erupting in France, the Moroccan government took an anti-intellectual, nationalist turn. As King Hassan II put it, “If no one wants to till the soil, if we all become intellectuals, we shall have to eat pencils.”7 [126] The government shifted its priorities towards religious education, strengthening the network of Quranic msids and accelerating the Arabization process.

In 1982, growing debt forced Morocco to turn to the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund for assistance. These institutions required [127] Morocco to liberalize parts of its economy and cut public spending by, among other means, sharply curtailing public sector hiring. This eliminated the primary employment pathway for Moroccan university graduates. It also drove the government, fearing the potential for unrest among a large class of unemployed graduates, to restrict access to public universities. With the government tightening its belt, other levels of the education system suffered as well—in the 1980s, elementary enrollment saw sharp declines.

King Mohammed VI’s accession to the throne in 1999 marked another turning point for the Moroccan educational system. Shortly after taking power, the new king launched a sweeping program of reform, declaring the coming years “a decade of education,” during which education would be expanded, decentralized, and otherwise modernized. These reforms were outlined in the Chartre National d’Education et de Formation [128] (National Education and Training Charter), which set ambitious goals: to increase enrollment significantly at all levels and eradicate illiteracy entirely by 2015, among others.

Other important changes quickly followed. In 2000, compulsory schooling [129] was extended to nine years, or from ages 6 to 15. And three years later, the Amazigh language [130] was introduced as a school subject.

But results remained disappointing, and a series of additional reforms soon followed. Among the most important was the Plan d’Urgence, the Emergency Plan, designed to run from 2009 to 2012, and l’École de Demain, which launched in 2012.

In 2019, Morocco officially adopted A Strategic Vision of Reform 2015-2030 [131] (2015-2030 Vision). The Vision outlines plans [132] to further expand education to all Moroccans, focusing on long-underserved rural and low-income communities. It establishes a goal of recruiting 200,000 new teachers to replace a rapidly aging workforce. It also aims [133] to ensure that students learn at least two foreign languages by the time they complete secondary school.

It also laid the groundwork for more significant changes, such as its suggestion that the licence-master-doctorat (LMD) system be replaced with a bachelor-master-doctor system. Although it was piloted in a handful of university programs in fall 2021, this change, discussed further below, was abandoned in early 2022.

Despite many remaining challenges, the Moroccan education system has made undeniable advances since independence. Enrollment at all levels has increased sharply, and a vast—if severely strained—network of public schools and universities provides education to all qualified children for free. And importantly, though there is room for further growth, literacy rates have improved nationwide. The adult literacy rate [134] increased from 30 percent in 1982, to 52 percent in 2004, to 74 percent in 2018. The youth literacy rate [135] has seen similar growth, rising from 44 percent in 1982, to 70 percent in 2004, to 98 percent in 2018.

Administration of the Education System

Although Morocco is technically a parliamentary constitutional monarchy, with executive and legislative power exercised by elected representatives, the king retains extensive and largely unchecked control over nearly all levels of government. At the highest level, the king has the power to dismiss the prime minister and dissolve parliament at will, although under the constitution adopted in 2011, the king is now required to appoint a prime minister from the party winning a plurality of the vote.

The ‘Alawi Dynasty and the Arab Spring Protests

The Arab Spring protests that rocked countries across the Middle East and North Africa in the early 2010s had less of an impact on Morocco, in large part due to the king’s undisputed secular and religious legitimacy. Unlike many of the shaky monarchies propped up and at times installed by Western powers in the twentieth century, Morocco’s monarchy enjoys widespread acceptance. The ‘Alawi dynasty is an Arab sharifian dynasty, tracing its lineage back to the prophet Muhammad, and has ruled Morocco since 1666. In the last years of colonial rule, the dynasty further burnished its image by adopting a nationalist posture and resisting French rule, moves which resulted in the exile of the king to Madagascar.

The palace’s quick response to the protests also muted their impact. On March 9, 2011, just weeks after the first protests [136] broke out, King Mohammed VI announced the formation of a committee to draft a new constitution that would continue “the process [137] of consolidation of our model of democracy and development.” Less than two months later, on July 1, a referendum approved the new constitution.

The new constitution addressed [138] a number of burning political issues. It adopted a relatively liberal stance on the question of the relationship between the state and religion and recognized Amazigh as one of the nation’s two official languages. The new constitution also expanded the power of the parliament, granting it more of a say in the country’s administration. But beyond minor limitations, the new constitution left the power of the king largely undiminished.

Morocco is divided into 12 administrative regions, three of which are situated partially or completely in the contested territory of the Western Sahara. Since 1975, when Spain ended its occupation, control over the sparsely populated territory has been disputed. Today, the governments of both Morocco, which refers to the region as the Southern Provinces, and the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) claim the territory. Aside from the U.S., which in late 2020 officially acknowledged [139] Moroccan control over the territory in exchange for Morocco’s normalization of relations with Israel, no other country recognizes Morocco’s sovereignty over the Western Sahara.

Although Moroccan policymakers have made decentralization a priority in recent decades, administration remains highly centralized. As of 2021, two ministries assume primary responsibility for the nation’s education system: the Ministry of National Education, Preschool, and Sports (Ministère de l’Education Nationale, du Préscolaire et des Sports, MEN [140]) and the Ministry of Higher Education, Scientific Research and Innovation (Ministère de l’Enseignement Supérieur, de la Recherche Scientifique et de l’Innovation, ENSSUP [141]).8 [142] Besides these, a number of smaller government bodies supervise various aspects of the educational system.

The MEN is responsible [143] for developing and implementing government policy for general and technical education at the preschool, elementary, secondary, technicien supérieur, and Classes Préparatoires aux Grandes Écoles (CPGE) levels. At these levels, the MEN designs curricula, determines teaching methods, oversees the development of school textbooks, and trains teachers and school administrators. It also oversees private institutions at these levels.

At the regional level, the MEN is assisted by Regional Academies of Education and Training (Académies Régionales d’Education et de Formation, AREF [144]) located in each of the country’s 12 administrative regions. Established in 2000 as part of the Moroccan government’s drive to decentralize education, AREFs ensure [145] that national educational and training policies are implemented at the regional level. Among their responsibilities is ensuring that private schools meet national standards.

Technical and vocational education and training (TVET) is regulated by the Department of Vocational Training (Département de la Formation Professionnelle, DFP [146]). The DFP is responsible [147] for developing national TVET policy and ensuring that TVET programs meet national quality standards. DFP [148] supervises and accredits [149] private TVET institutions (établissements de formation professionnelle privée, EFPP) and programs. As the main public provider [150] of TVET qualifications, the Office for Vocational Training and Work Promotion (Office de la Formation Professionnelle et de la Promotion du Travail, OFPPT [151]) often assists the DFP in administering and developing the country’s TVET system.

In Morocco, ENSSUP [152] is responsible for developing and implementing policies for the higher education system. It supervises and accredits both public and private higher education institutions and programs. In this, it is aided by the National Agency of Assessment and Quality Assurance in Higher Education and Scientific Research (Agence Nationale d’Evaluation et d’Assurance Qualité de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche Scientifique, ANEAQ [153]). ANEAQ evaluates institutions and programs and issues accreditation recommendations to ENSSUP. In addition, ANEAQ also oversees partnership arrangements [154] between domestic and international higher education institutions.

Academic Calendar and Language of Instruction

For elementary, secondary, and vocational training institutions, the school year [155] lasts from September to mid-June or early July. For higher education institutions, the academic year is roughly the same, beginning in early September and ending in July. The academic year at the higher education level is divided into two semesters, each containing 15 to 16 weeks of teaching and assessment.

The language of instruction at Moroccan schools and universities has fluctuated over the years, and language policy has long been a subject of intense discussion.

In the early days of independence, a strong sense of nationalism encouraged the government to adopt a policy of Arabization, with the goal of eventually replacing French with Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) throughout the education system. But Arabization was only ever partially implemented. It left private schools, as well as certain scientific and technology subjects at public universities, untouched. The Arabization policy was officially abandoned [156] in 2016, when the government announced plans that aimed to foster bilingual (MSA and French) competencies.

Despite Arabization, French continued to be used throughout the education system. In public schools, French is a required subject of study beginning in grade 3. At many private schools, French is used as the language of instruction, with Arabic taught as a foreign language. At the higher education level, French is widespread, especially for STEM subjects. In 2019, a law was passed [44] requiring that certain scientific and technology subjects be taught in French at lower and upper secondary schools.

The place of English in Morocco’s education system is growing in importance each year. A 2021 British Council survey [97] found that more than two-thirds of young Moroccans believe that English will surpass French as the country’s main foreign language in the next five years, a prospect welcomed by nearly three-quarters of the respondents.

In fact, many Moroccans are calling for a shift from French to English at the country’s schools and universities. Although the Moroccan government has long ruled out [98] replacing French with English, it too has taken notice of the growing popularity of English. The government has introduced reforms [157], which will go into effect in 2023, that will require university students to pass an English language proficiency examination at the lower intermediate level before they can receive their undergraduate diploma. ENSSUP has also created new programs [158] that are offered entirely in English.

Currently, English, and other foreign languages, such as Spanish, are introduced in ninth grade at public schools, although private schools may offer foreign language courses earlier. Plans are currently in place to introduce English to children at age 12 instead of 15, and the MEN recently announced [159] plans to hire more teachers of English at the lower secondary level.

After decades of official silence—and, at times, hostility—the government has recently come to acknowledge the prominence of Tamazight languages in Morocco. In 2001, the government created the Royal Institute of Amazigh Culture (Institut Royal de la Culture Amazighe, IRCAM), giving it the “mission of safeguarding [160], promoting, and strengthening Amazigh culture in education and the national media, and managing its use locally and regionally.” IRCAM developed the Tifinagh-IRCAM alphabet [161], which is used to transcribe Tamazight in Morocco. As noted earlier, the constitution adopted in 2011 recognized Tamazight as an official language.

Beginning in 2003, certain public elementary schools began teaching Tamazight as a subject. A law passed in 2019 [162] will require all Moroccans, including those enrolled in private schools, to study Tamazight. At the higher education level, Tamazight is taught [163] as a subject in only a handful of public universities.

There have also long been calls to formally introduce Moroccan Arabic—darija—into the school system. Studies suggest [164] that most public elementary and secondary schools already use darija in the classroom, although it is nowhere taught as a formal subject. Despite its widespread use, the government currently has no plans to introduce darija.

Early Childhood Education (ECE)

Compared with those of many other MENA countries, Morocco’s early childhood education (ECE) sector is well developed. Currently, preschool (enseignement préscolaire) lasts for two years and, since 2020, is free and compulsory for all four- and five-year-old children. A national curriculum, which a July 2022 USAID analysis [165] described positively as a “solid competency-based curriculum that develops children’s holistic skills progressively,” guides preschool learning across the country.

Historically, the overwhelming majority of preschool education [166] in Morocco was conducted in msids [167], the small, private Quranic schools described earlier as often attached to mosques. They typically offer religious education as well as basic numeracy and literacy courses. While most students pass from msid preschool classes to general academic elementary schools, a small number remain in religious schools, where they continue their studies in a formal stream of religious education known as enseignement original, or traditional education.

But recent initiatives, for which the government has earmarked significant funds, are driving an expansion of preschool enrollment in public schools. In 2018, the government launched an initiative aimed at universalizing preschool education and extending its length from two to three years, beginning with three-year-old children. It hopes to expand preschool enrollment to 100 percent of all four- and five-year-olds by 2027/28 and to all three-year-olds by 2028. As of 2020, 60.4 percent [168] of eligible children were enrolled in a preschool program.

To achieve these goals, the government aims to train 28,000 new preschool teachers and provide in-service training to the 27,000 already practicing. It also plans a significant expansion of preschool facilities. As of 2021, the initiative had constructed 8,000 new preschools across the country.

Much of the government’s focus is on rural areas, where a World Bank report [169] notes that just 61.8 percent of four- and five-year-old children are enrolled in preschool (and just 54.5 percent of rural girls), compared with 78.7 percent of similarly aged children in urban areas. In rural areas, the government aims to increase the number of preschool facilities from 1,200 to 7,200.

Elementary Education (Enseignement Primaire)

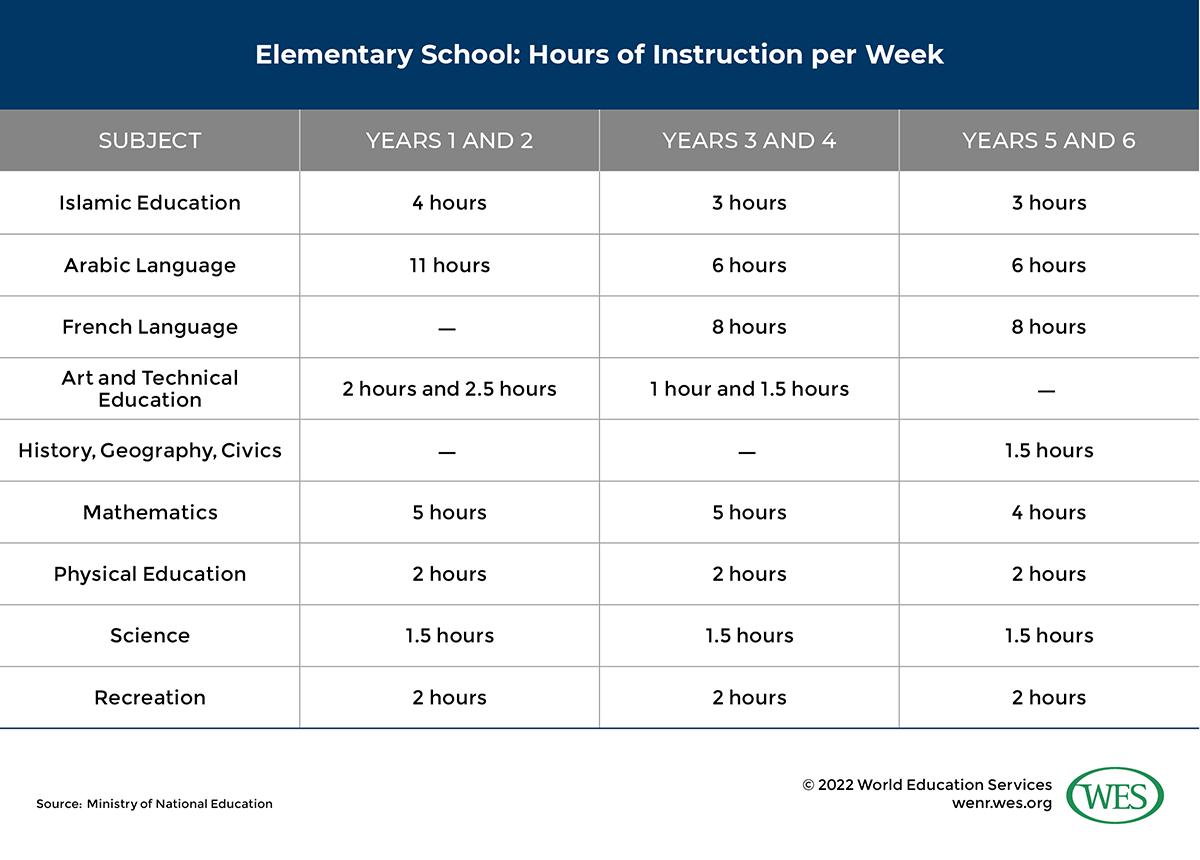

Elementary education (enseignement primaire) is compulsory in Morocco for children 6 to 12 years of age. At public elementary schools, Arabic is the principal language of instruction, with French language courses introduced in grade 3.

Elementary education is divided into two cycles [170]. The first, lasting two years, continues the holistic competency development begun in preschool; the second, which lasts through the remaining four years, introduces progressively more advanced coursework and skills. The core subjects [171] of study are (Modern Standard) Arabic language; art and technical education; French language; philosophy and Islamic thought; history, geography, civics and Islamic civilization; mathematics; physical education; and the sciences.

Enrollment in elementary schools is more or less universal. The elementary gross enrollment ratio (GER) stood at 113.4 percent [173] in 2021. Growth has been particularly impressive in rural areas, where only a little more than three-quarters [174] of all children between the ages of 6 and 11 were enrolled in school in 2000/01.

Unlike at the preschool level, most Moroccan elementary school students, around 84 percent [166] in 2021, are enrolled in public schools. The rate of grade retention, once a persistent problem, has fallen in recent decades. The number of students repeating grades at the elementary level fell to 4.8 percent [175] in 2020, down from 8.4 percent in 2010 and 13.3 percent in 2000.

After completing six years of elementary education, students are awarded a Certificate of Primary Studies (Certificat des études primaires).

Lower Secondary School (Enseignement Secondaire Collégial)

Secondary education in Morocco is divided into lower secondary school (enseignement secondaire collégial) and upper secondary school (enseignement secondaire qualifiant).

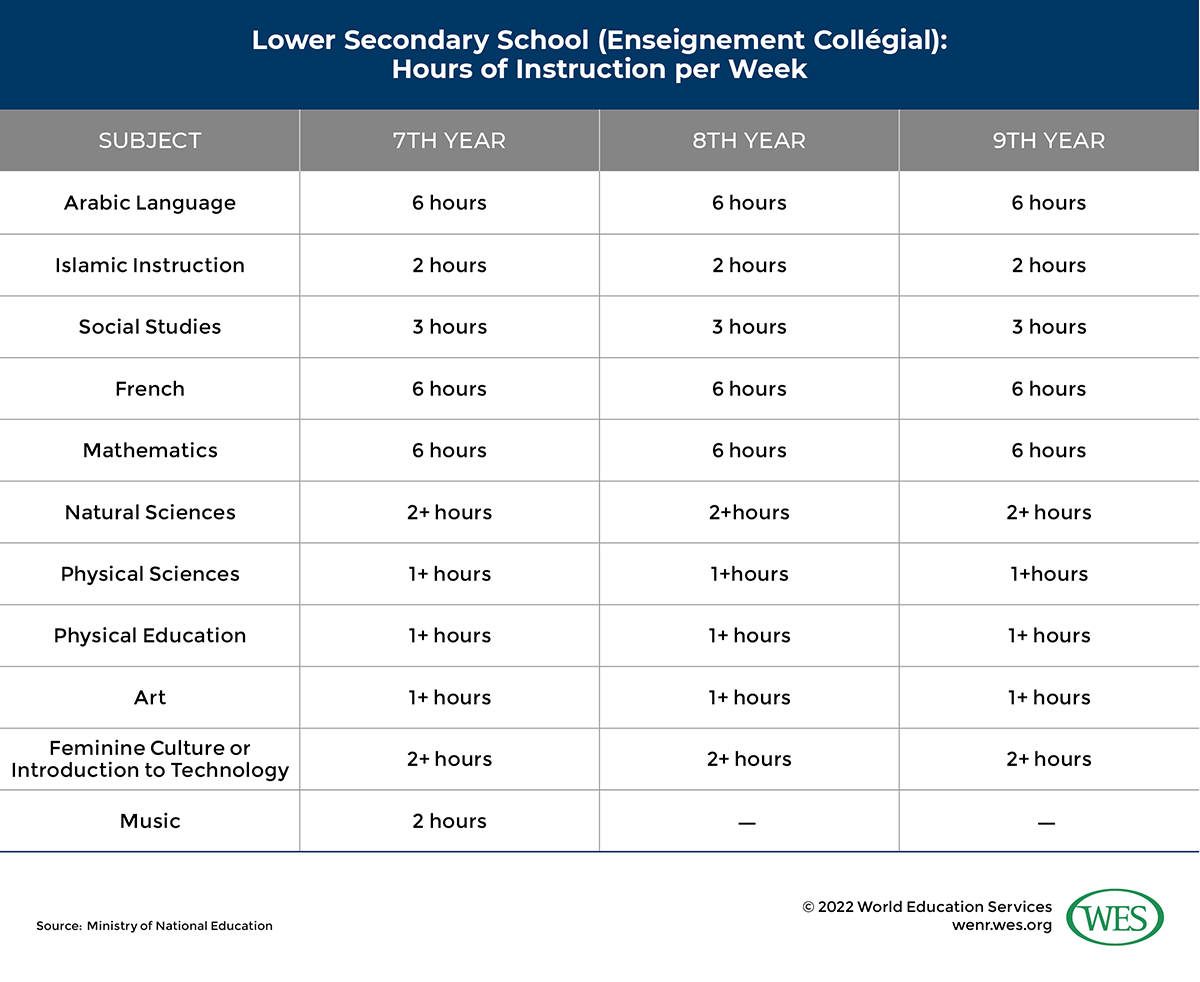

Lower secondary school, commonly referred to as collège, is compulsory and three years in length; it is accessible to students successfully completing six years of study in elementary school.

Courses [176] include the Arabic language, fine arts, French language, home economics or introduction to technology, Islamic education, mathematics, music, natural sciences, physics, physical education, and social sciences (history, geography, and civics).

Enrollment in collège has grown swiftly in recent decades. The lower secondary GER stood at just 51 percent [173] in 2000, growing to 79.2 percent in 2010 and 99 percent in 2021.

At the end of the third year of collège, students sit for a regional, standardized exam [178]. Those passing the exam are awarded a Lower Secondary School Certificate (Brevet d’Enseignement Collégial, BEC), which is required for entry to the final stage of secondary education.

Upper Secondary School (Enseignement Secondaire Qualifiant)

Over the past two decades, enrollment trends at the upper secondary level have mirrored those at the lower secondary level, albeit from a much lower starting point. In 2000, the upper secondary GER stood at just 26.4 percent [173], growing to 48 percent in 2010 and 68.1 percent in 2021.

Despite encouraging growth, large disparities in access exist. Although recent data are unavailable, enrollment in urban areas has long been far higher than in rural areas.

At the upper secondary level, girls also begin to outnumber boys. Despite higher enrollment ratios for boys at both the elementary and lower secondary levels, the enrollment ratio for girls exceeds that for boys at the upper secondary level. In 2021, the upper secondary GER for males was 66.2 percent, while it was 70.1 percent for females.

Outcomes at public schools are also often significantly worse than at private schools. According to a May 2019 study [179] by the Conseil Supérieur de l’Éducation, de la Formation et de la Recherche Scientifique (CSEFRS), the average score of public school students on the PIRLS 2016 was 340 out of 1000, compared to 461 for private schools students. Private school students also tend to come from better off families. The same study found that just 35 of public-school students had at least one parent working a white-collar job, compared to 91 percent of private school students. It also found that only 26 percent of public-school students had at least one parent with a post-secondary education, compared to 66 percent of private school students.

To enroll in an upper secondary school, which are commonly referred to as lycées, students must have obtained a BEC.

Upper secondary school lasts three years and offers three principal study tracks, although terminology has changed over the years: general secondary (enseignement secondaire général), technological secondary (enseignement secondaire technique), and professional secondary (enseignement secondaire professionnel). Each track is further divided into various streams.

In the first year of lycée, students in all tracks follow a core syllabus, known as the tronc commun. At the end of the first year, students sit for a regional, standardized examination [178], which tests their knowledge of general subjects such as Arabic language and culture, a foreign language, and Islamic education.

In the second and third years, which are known as the cycle de baccalauréat, students take courses specific to the track and stream they have chosen.

The general secondary track is divided into the following branches [180]: literature and the humanities, mathematics, experimental sciences (agricultural, life and earth sciences, and physical science), and traditional education (Arabic language and Sharia law).

Although the time devoted to each subject differs according to stream, students in the general track study [181] a common set of subjects: literature, languages, Islamic education, physical education, translation, mathematics, natural sciences, physics, and social science (such as history and geography). Students in this track typically complete 27 to 36 hours of lessons per week.

The technology track is divided into six groups of streams: mechanical engineering (génie mécanique), electrical engineering (génie electrique), civil engineering (génie civil), chemical engineering (génie chimique), economics (génie economique), and agronomic engineering (génie agronomique). These streams are further subdivided [181] as follows:

| Enseignement Secondaire Technique Fields and Streams | |||||

| Génie mécanique | Génie électrique | Génie civil | Génie chimique | Génie économique | Génie agronomique |

| Sciences et Techniques | L’ectrotechnique | Conception et bâtimenthiques | Chimie | Sciences économiques | Sciences agronomiques |

| Fabrication mécanique | Électronique | Arts et industries graphiques | Techniques de gestion comptable | ||

| Fonderie | Techniques de gestion administrative | ||||

Students in all technical streams take compulsory courses in literature, languages, Islamic education, history, geography, physical education, mathematics, and physics. The remaining courses are specific to their specialty. Students in the technical track complete 30 to 37 hours of lessons per week.

In 2014/15, the DFP introduced the baccalauréat professionnel (professional baccalaureate [182], or bac pro). The professional track is divided into agriculture, construction engineering and public works, services (such as food, hospitality, and so on), electrical engineering, and mechanical engineering. The bac pro [183] is offered in partnership between lycée and TVET institutions, with lycées teaching general education courses and TVET institutions responsible for vocational subjects and practical internships.

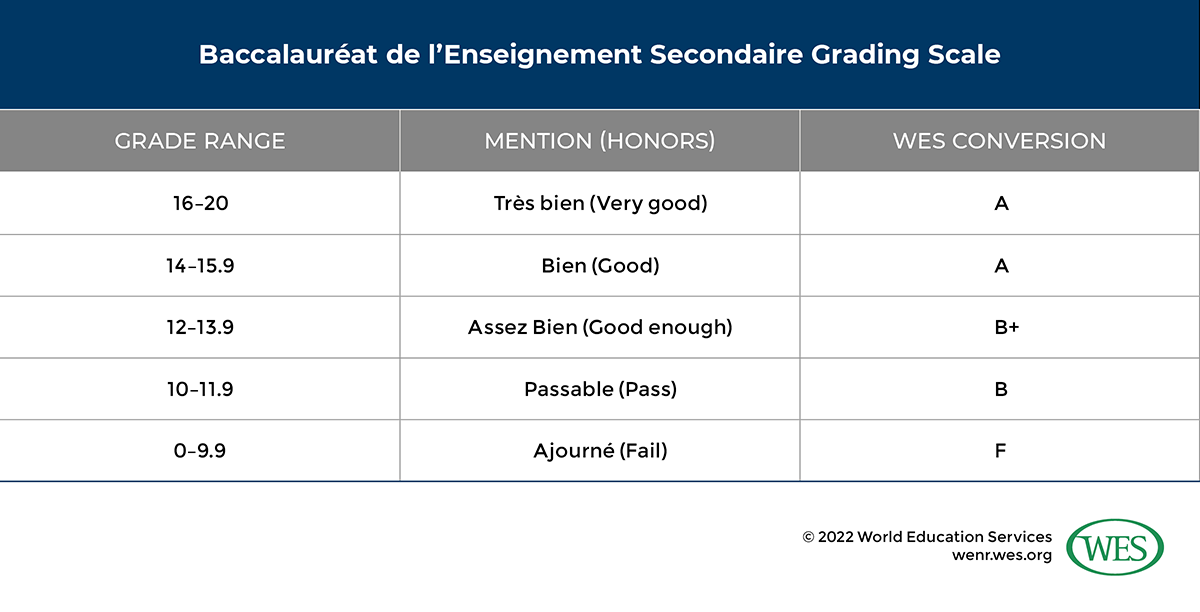

After completing three years of study at the upper secondary level, students in all tracks take a national baccalauréat examination administered by the National Center for Assessment and Examination [180]. The bac exam tests students on certain general and specialized subjects, plus a second foreign language.

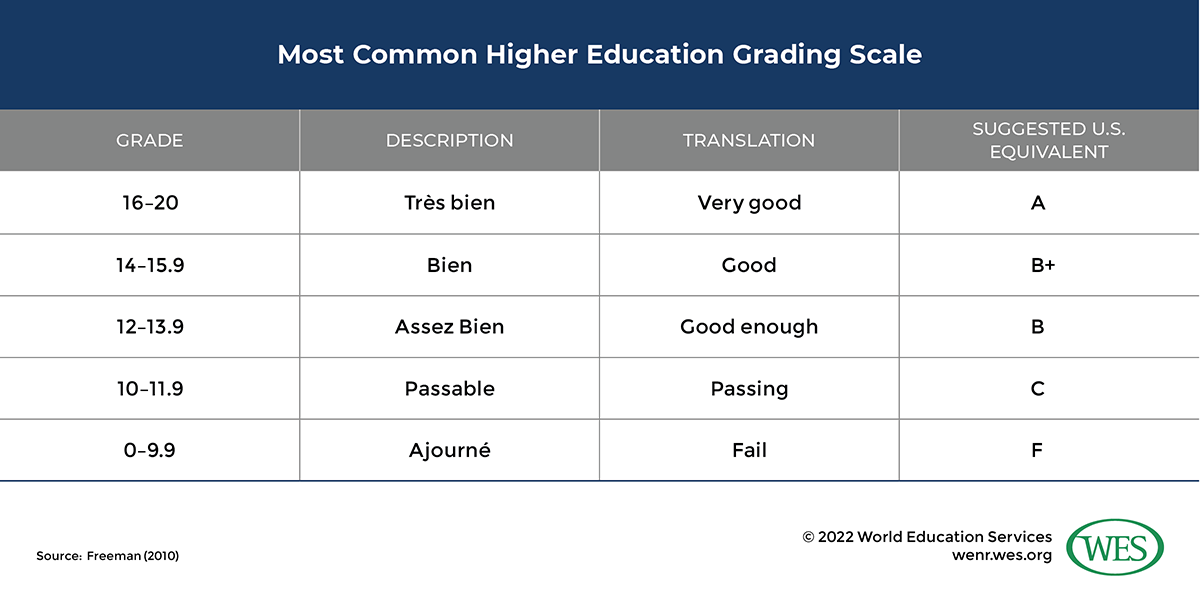

Grading follows the French model, with a 0 to 20 scale and a minimum passing grade of 10. Students successfully completing upper secondary and passing the bac exam are awarded the Certificat de Baccalauréat (Baccalaureate Certificate). Students receive various mention (honors) depending on their grades, the highest mention being très bien (very good), followed by bien (good), assez bien (satisfactory), and passable (pass).

Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET)

Despite concerted efforts to improve the sector, the reputation of technical and vocational education and training (TVET) in Morocco remains poor, with many considering it an option of last resort, attracting only students who are struggling academically. This reputation—common to technical education around the world—may in part stem from a mismatch between the training provided and the needs of employers, a common complaint in Morocco. A recent report [19] found that unemployment for those holding the diplôme de technicien spécialisé, the highest TVET diploma, was 20.5 percent, second only to those holding a licence fondamentale (21 percent), an undergraduate university degree.

Both public and private institutions in Morocco offer TVET programs [185]. The largest public TVET provider [150] by far is the Office for Vocational Training and Work Promotion (Office de la Formation Professionnelle et de la Promotion du Travail, OFPPT [151]). Through hundreds of establishments [186] (établissements) across the country, the OFPPT trains around half a million students in more than 300 professions each year. Besides OFPPT, various government ministries also organize training programs to develop professionals in fields related to the ministries’ work.

Private TVET institutions (établissements de formation professionnelle privée, EFPP) also train a significant number of Moroccans, although only some of their training programs are recognized by the state. In 2017/18, 1,365 [182] EFPPs offered TVET training programs, nearly double the number of public establishments. Still, EFPPs tend to be small. Only about 20 to 25 percent of all TVET students enroll in EFPPS, often those who failed to obtain entry to OFPPT programs.

To open, all EFPPs must be evaluated by and obtain authorization [149] from the Department of Vocational Training (Département de la Formation Professionnelle, DFP [146]). To offer and award accredited diplomas, EFPPs must then seek sector-specific accreditation [187] from DFP. In 2011, around 12,000 students, or 16 percent of all students enrolled in private TVET institutions, were enrolled in DFP-accredited programs.

Both public and private institutions offer four levels [188] of accredited TVET programs. These programs are available in a number of professional fields, from aeronautics and automobiles to textiles and tourism. Programs typically consist of both theoretical coursework and practical training, such as an internship with a company. Some TVET programs are offered on a part-time or evening basis.

Spécialisation-level programs are open [189] to students completing elementary education. Program lengths [185] can vary from six months [182] to two years. Students successfully completing specialization-level programs earn a Diploma of Professional Specialization (Diplôme de Spécialisation Professionnelle, DSP).

Students obtaining a DSP can continue their technical training in a qualification-level program, which is also open to students holding a BEC who pass a competitive examination. Qualification-level programs typically last one [190] to two years [191]. Students completing a program earn a Diploma of Professional Qualification (Diplôme de Qualification Professionnelle, DQP). Students obtaining a DQP can continue to technician-level programs or enroll in a Bac Pro program.

Technicien-level programs are open to students possessing a DQP in a similar specialization and those in the second year of upper secondary education (grade 11) who pass a competitive examination. These programs typically last two years and lead to the award of a Diplôme de Technicien (Technician Diploma, DT).

Technicien Spécialisé-level programs are open to those with a DT in a similar specialization or to bac holders passing a competitive examination. They typically last two years and lead to the award of a Diplôme de Technicien Spécialisé (Diploma of Specialized Technician, DTS). Students obtaining a DTS can continue to study in related higher education programs.

Students can also enroll [192] in similar two-year post-bac programs at technical lycées and post-secondary institutions leading to a Brevet de Technicien Supérieur [193] (BTS) (Higher Technician’s Certificate). BTS programs are available [194] in two business sectors: the industrial sector and the commercial and service sector.

In addition to these diploma programs, students with adequate reading, writing, and arithmetic skills (typically those completing grade 6) can enroll in a training program [195] to obtain a Certificat d’Apprentissage Professionnel [196] (CAP), which typically lasts from six months to one year. These programs are typically conducted both at a training center and in a workplace.

Teacher Education

Until recently, teacher training in Morocco was highly fragmented. Different types of institution [197]s prepared teachers for different stages of the education system, each maintaining a distinct pedagogical approach.

Elementary school teacher training centers (Centres de Formation des Instituteurs, CFI) trained elementary school teachers. CFIs evolved significantly following their creation in 1956. Initially open to candidates holding just a BEC, program requirements were gradually raised over the decades. In 1980, admission to the program, which lasted two years, was restricted to those holding a baccalauréat.

In 2007, the program was changed again. Entry requirements were raised still further, restricting admission to those holding a two-year, post-secondary qualification, the Diploma of General University Studies (Diplôme d’Etudes Universitaire Générales, DEUG), and the length of training was reduced, from two years to one.

Regional pedagogical centers (Centres Pédagogiques Régionaux, CPR) trained lower secondary school teachers. From 1986, the training program was divided into two streams, or cycles. The cycle général (general cycle) was accessible to holders of a baccalauréat and required two years of study. The cycle pédagogique (pedagogical cycle) was open to those with a two-year post-bac DEUG and required one year of study.

Écoles Normales Supérieures (Higher Normal Schools) principally trained upper secondary school teachers, although a few also provided training to technical and physical education teachers. The upper secondary teacher training program lasted one year, and admission was restricted to those holding a licence. Admission to technical and physical education programs required only a baccalauréat, although the courses of training themselves lasted four years.

Changes to this system began with the adoption of the Charte National d’Education et de Formation (National Education and Training Charter, CNEF) in 2000, although they really only picked up following the introduction of the 2009-2012 plan d’urgence.

At the institutional level, these changes simplified and unified teacher training. CFIs and CPRs were merged and reorganized into a network of regional centers for educational and training professions (Centres régionaux des métiers de l’éducation et de la formation, CRMEF). ENSs were absorbed by public universities, which now took on a greater role in teacher training.

The training program itself was divided into two stages: initial and qualifying training (formation qualifiante). Initial training occurs at the university level, where students are required to take certain university education courses (filières universitaires d’éducation, FUE).

The second stage, qualifying training, is conducted at CRMEFs. Only those who have obtained a university licence, completed the required FUEs, and passed a national admission examination, which consists of written and oral parts, are eligible to enroll at a CRMEF. CRMEF trainees are also expected to have mastered both Arabic and French.

Qualifying training programs last one year, with training split between the CRMEFs and local schools. At the schools, trainees get hands-on experience in teaching—60 percent of all hours in qualifying training programs are devoted to practical training.

Qualifying training programs are organized according to the three school cycles, and successful students are awarded one of the following qualification certificates:

- The Certificat de la Qualification Pédagogique à l’Enseignement Primaire (Certificate of Qualification to Teach in Elementary Schools)

- The Certificat de Qualification Pédagogique d’Enseignement Secondaire Collégial (Certificate of Qualification for Teaching in Lower Secondary School)

- The Certificat de la Qualification Pédagogique à l’Enseignement Secondaire Qualifiant (Certificate of Qualification to Teach in Upper Secondary Schools)

CMREFs also offer more advanced teacher training qualifications. The aggregation cycle [198] (cycle d’agrégation), established in 1986, prepares high-level secondary and post-secondary school teachers. Teachers completing this training typically teach the final years of upper secondary school or in Classes Préparatoires aux Grandes Ecoles (CPGE) and executive training institutions (établissements de la formation des cadres).

To sit for the aggregation examination [199] (concours de l’agrégation), students must complete a Cycle de Préparation à l’Agrégation (CPA) program. A typical CPA program lasts three years, although depending on their prior education and experience, students can be admitted to the second or even third year of the program. Admission is based on a competitive examination, which is open to students completing the second year of the CPGE or those completing the first cycle of an LMD higher education program.

Those passing the concours de l’agrégation become a “professeur agrégés de l’enseignement secondaire qualifiant” and are awarded a Certificat d’Agrégation de l’Enseignement Secondaire (Aggregation Certificate of Secondary Education).

Higher Education

Access to higher education is restricted to students earning a baccalauréat. Bac pass rates have grown quickly in recent years, rising from 48.1 percent [200] in 2010 to 72.2 percent in 2019. Alongside this, the number of students sitting for the bac examination has risen as well. As a result, the number of students passing the bac grew from 136,721 [201] in 2010 to 280,406 in 2019.

All students earning a bac are guaranteed admission to public universities, but only in certain faculties or colleges. These faculties, known as accès ouvert, or open-access faculties, include the arts and humanities; the basic sciences (biology, chemistry, and physics); legal, economic, and social sciences; and traditional education. Open-access faculties enroll the majority of Moroccan university students. In fact, the arts and humanities faculties and legal, economic, and social sciences faculties alone enroll nearly three-quarters (74 percent) of all public university students.

Admission to other faculties, known as accès régulé, or restricted-access, faculties, is far more selective, as the name implies. In addition to obtaining a bac, prospective students must take an entrance exam, competing with Moroccans and international students for access to a strictly controlled number of seats. Restricted-access faculties include the following: business and management, dental medicine, education, engineering, medicine and pharmacy, paramedics, sports sciences, science and technology, teacher training, and technology.

These faculties, especially those in technical and exact sciences, are far more prestigious than the other public university faculties. But they also enroll far fewer students than open-access faculties. Just 13 percent of all public university students in Morocco were enrolled in restricted-access faculties in 2021/22.

Morocco’s growing youth population and its rising bac pass rates have helped spark a rapid increase in university enrollment. Over the past two decades, Morocco’s tertiary GER has increased from 10.2 percent [202] in 2000, to 14.6 percent in 2010, to 40.6 percent in 2020. Over the past 15 years, enrollment has grown by over 250 percent in public universities alone, rising from 292,776 [203] in 2007/08 to 1,061,256 in 2021/22.

Most of this growth has been in open-access public faculties. While enrollment in restricted-access programs increased by around 66,000 students to 137,533 between 2012/13 and 2021/22, enrollment in open-access programs increased by about 454,000 students to 923,723.

This rapid growth has severely strained Morocco’s public universities. The government hopes the private sector can help ease some of this pressure—compared with other countries in the region, higher education in Morocco remains a largely public affair. Just 62,600 students, or around 5 percent of all higher education students, were enrolled in private institutions in 2021/22. The government wants that number to increase to 20 percent in the coming years.

Overcrowding has negatively impacted the quality of education at open-access public faculties. Dropout rates are extremely high among students enrolled in these faculties. MEN officials noted in 2018 that a staggering 47.2 percent [204] of university students drop out before they obtain a degree. And the time it takes them to complete a degree is quite high. A 2021 British Council report [99] notes that it is not unusual for students to require six years to graduate from a standard three-year undergraduate program.

Graduates of open-access faculties also face grim employment prospects. In 2015, Lahcen Daoudi, then minister of higher education, said [205] that the “the fate of most humanities and law students is unemployment.” They produce a majority of Morocco’s “diplômés chômeurs,” or graduate unemployed. As of 2018, four years after graduation, 18.7 percent [19] of open-access graduates were unemployed. Among other post-secondary graduates, only post-secondary TVET graduates had higher unemployment rates (20.5 percent) four years after graduation.

Part of the reason is a mismatch between the education system and the labor market. Employers constantly complain of a lack of skills among university graduates, and countless reports decry the low quality of Moroccan university education. The World Economic Forum identified an inadequately educated workforce as one of the most problematic factors for doing business in Morocco in its 2017/18 Global Competitiveness Index [206], ranking Morocco’s higher education and training 101 out of 137 countries.

Experts believe part of the reason for the mismatch between university education and the labor market lies in the colonial heritage of the university system. Established to provide a general education for future civil servants, the system has been unable to reorient itself as the public sector has become a narrower part of the wider labor market. These challenges extend back at least to 1983, when the IMF forced Morocco to sharply curtail government hiring, but they have been exacerbated by the rapid increase of university enrollment in recent years. Today, just 5 percent of young Moroccans work in the civil service.9 [207]