[1]

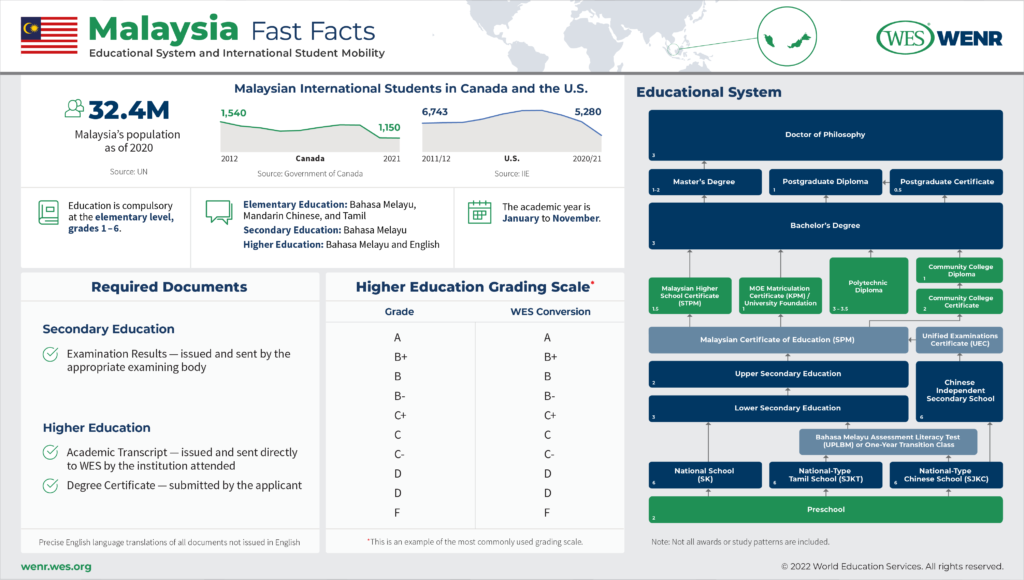

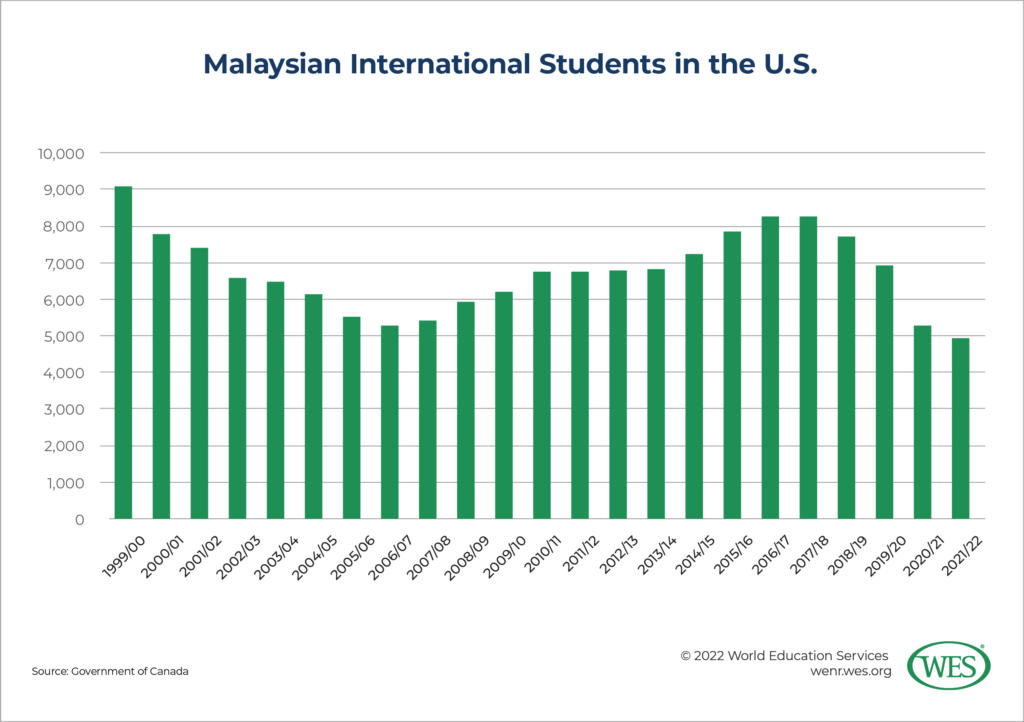

[1]Although the U.S. is one of the most popular destinations for Malaysian international students, enrollment has declined steeply since the 2017/18 academic year.

Malaysia is a multicultural, multilingual, multi-ethnic society. The country is composed of three major ethnic groups. Indigenous Malaysians, or Bumiputera, which literally translates [2] as “princes of the soil,” are numerically dominant—their largest single group, Malays, makes up slightly more than half of the country’s population. Bumiputera coexist with two large minority communities: Chinese and Indian Malaysians. These communities make up around 23 percent and 7 percent of the country’s population, respectively.

This ethnic diversity has played a defining role in Malaysia’s modern history. Public policy decisions have long been shaped by the often-conflicting goals of protecting the special privileges of various ethnic communities and bringing all Malaysians together as equal members of a unified nation. Over the years, attempts to balance these goals have produced a succession of uneasy compromises and differential approaches to the treatment of different ethnic groups.

Ethnic considerations have also strongly shaped Malaysian education. At some levels of the education system, three parallel systems exist, each catering to a specific ethnic group while referring to nationwide standards and guidelines. At others, all Malaysians can gather under a single roof, although doors open more easily for some ethnic groups than others.

The Colonial Legacy

The seeds of this situation were planted by the policies of the British Empire. Beginning in the late eighteenth century, the British slowly expanded their control over the Malay peninsula and northern Borneo, attracted by the land’s rich reserves of tin and rubber.

But exploiting those reserves required a sizable workforce. Unable to attract enough native Malays to work in the colony’s lucrative tin mines and rubber plantations, the British turned increasingly to immigrant labor. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the British actively aided immigration from India and Sri Lanka to work on rubber plantations and in public works. They also encouraged immigration from South China to work in tin mines, which even prior to the arrival of the British had often been owned and operated by immigrants from China.1 [4]

Although the British worked to coopt the Malay aristocracy, towards the majority of the Malay population, who largely lived as subsistence farmers and fishermen, the British adopted a policy they termed “minimum interference.” While this policy allowed most Malays to continue cultivating the soil and fishing, at least in the short term, it also sharply separated them from the economic centers of the country and its growing money economy.2 [5]

As a result, at independence in 1957, huge disparities in wealth separated Bumiputera and non-Bumiputera, while occupation and geographic location closely followed ethnic divisions. Non-Bumiputera, and Chinese Malaysians in particular, tended to live in cities along peninsular Malaysia’s western coast, where they dominated the nation’s trade and commerce, while most Malays and other Bumiputera remained scattered in rural communities working the soil.

While Chinese Malaysians tended to dominate the economy, Bumiputera, and Malays in particular, dominated politics.3 [6] The constitution [7] ratified in 1957 made Bahasa Melayu, the language spoken by most Bumiputera, the new nation’s only official language. More controversially, the constitution also asserted the privileged status of Malays and other Bumiputera. Article 153 of the constitution made it the responsibility of the head of state to “safeguard the special position of the Malays and natives of any of the States of Sabah and Sarawak.”

Malaysia’s Varied Geographic and Cultural Landscape

Malaysia is divided by the South China Sea into two regions, separated by hundreds of miles: Peninsular, or West, Malaysia, and East Malaysia. Peninsular Malaysia, the location of Kuala Lumpur, the country’s capital and largest city, borders Thailand to the north and, across the Straits of Johor, Singapore to the south. East Malaysia, located on the north shore of the Island of Borneo, shares land borders with both Indonesia and Brunei, and sea borders with the Philippines and Vietnam.

Indigenous Malaysians, or Bumiputera, make up around 70 percent [8] of the Malaysian population. The largest of these groups is the Malays, who alone made up slightly more than half [9] of the total population in 2015. While Malays are concentrated in Peninsular Malaysia, their numbers in East Malaysia are more limited. There, other Bumiputera communities are in the majority. The Ibans of Sarawak and the Kadazandusuns of Sabah are East Malaysia’s largest ethnic communities. In both East and West Malaysia, Bumiputera tend to dominate rural communities, where their ancestors long tilled the soil or fished the seas.

Bumiputera coexist with large minority communities, notably those of Chinese (22.8 percent) and Indian (6.6 percent) descent. Chinese and Indian Malaysians are found in greatest proportion on the west coast of Peninsular Malaysia, although a large Chinese community also exists in Sarawak in East Malaysia. Unlike Bumiputera, Chinese and Indian Malaysians are often concentrated in cities, while their numbers are noticeably lower in rural areas of the country.

Religion largely follows these ethnic lines. The country’s Muslims, most of whom are Malays, make up around 63.6 percent [10] of the country’s total population.4 [11] Buddhists, the majority of whom are ethnic Chinese, make up 18.8 percent of the country’s population; Christians, the majority of whom are non-Malay Bumiputera, make up 9 percent of the population; and Hindus, most of whom are ethnic Indians, make up 6.2 percent of the population.

These communities speak more than 100 languages [12]. Most Malaysians, both Bumiputera and non-Bumiputera, speak Bahasa Melayu, or Standard Malay, the standardized form of the language native to the country’s Malay population and the country’s only official language. Other Bumiputera communities speak dozens of other Indigenous languages.

Chinese Malaysian communities speak various dialects of Chinese, the most common of which is Mandarin Chinese. However, the languages spoken in South China—such as Hokkien, Hakka, and Cantonese—where many Chinese Malaysians trace their heritage, are also widespread.

Most Indian Malaysians are ethnic Tamils and speak the Tamil language, although some other South Asian languages, such as Malayalam and Telugu, are also spoken.

Ethnic Unrest and the New Economic Policy (NEP)

The tensions inherited from the colonial era exploded in 1969. In that year’s elections, ruling coalition parties lost ground to the opposition, and, notably, to two ethnic Chinese parties. In the capital, the outcome sparked riots, and fighting soon broke out between ethnic Malays and Chinese and Indian Malaysians, killing hundreds.

The riots had a profound impact on Malaysia, revealing the fragility of the country’s ethnic balance. They prompted attempts to foster national unity, including the declaration of the Rukun Negara, which espoused a national philosophy of unity and harmony among all of Malaysia’s ethnicities.

But the riots also propelled leaders to power who believed that historical wrongs had disadvantaged Malaysia’s Bumiputera communities, and that easing ethnic tensions would require preferential treatment of Malays and other Bumiputera. In 1970, despite making up more than half the population, Bumiputera held just 2.4 percent [13] of all shares in the stock market, while Chinese Malaysians, who then made up a little more than one-third of the population, held 27 percent.

In 1971, these leaders introduced the New Economic Policy [14] (NEP), which they hoped would promote national unity through the elimination of poverty among all Malaysians and the restructuring of “society so that the identification of race with economic function and geographical location is … eliminated.”

The NEP gave Malays and other Bumiputera preferential treatment [13] in all spheres of public life. It reserved senior positions in the civil service for Bumiputera, favored Bumiputera-owned businesses in government contracting, entitled Bumiputera to significant discounts for new housing, and set minimum levels of Bumiputera ownership for all public companies.

It also spurred similar changes to the education system. In the years that followed, the government established special schools, scholarships, and universities exclusively for Malays and other Bumiputera students.

The politicization of education along ethnic lines also solidified the parallel school system first developed by British colonial authorities. Under this arrangement, three separate elementary school systems existed side-by-side: national schools, which were fully funded by the government and taught in Bahasa Melayu, and Chinese and Tamil vernacular schools, which were only partially funded by the government.

Despite attempts to roll back some of the policies unleashed by the NEP, ethnicity continues to loom large in Malaysia today. But its prominence has often obscured other significant divisions in the country. For example, while Malaysia’s swift economic rise has, since the end of the twentieth century, improved living standards for many, it has left some behind. While Kuala Lumpur and other cities in Peninsular Malaysia are booming, many rural communities, especially those in East Malaysia [15], remain mired in poverty.

As Malaysia transitions to a high-income country [16] over the next decade, it will need to ensure that Malaysians of all ethnicities, whether they live in cities or rural areas, in East Malaysia or West Malaysia, can access the economic and educational opportunities that prosperity can offer.

Inbound Student Mobility

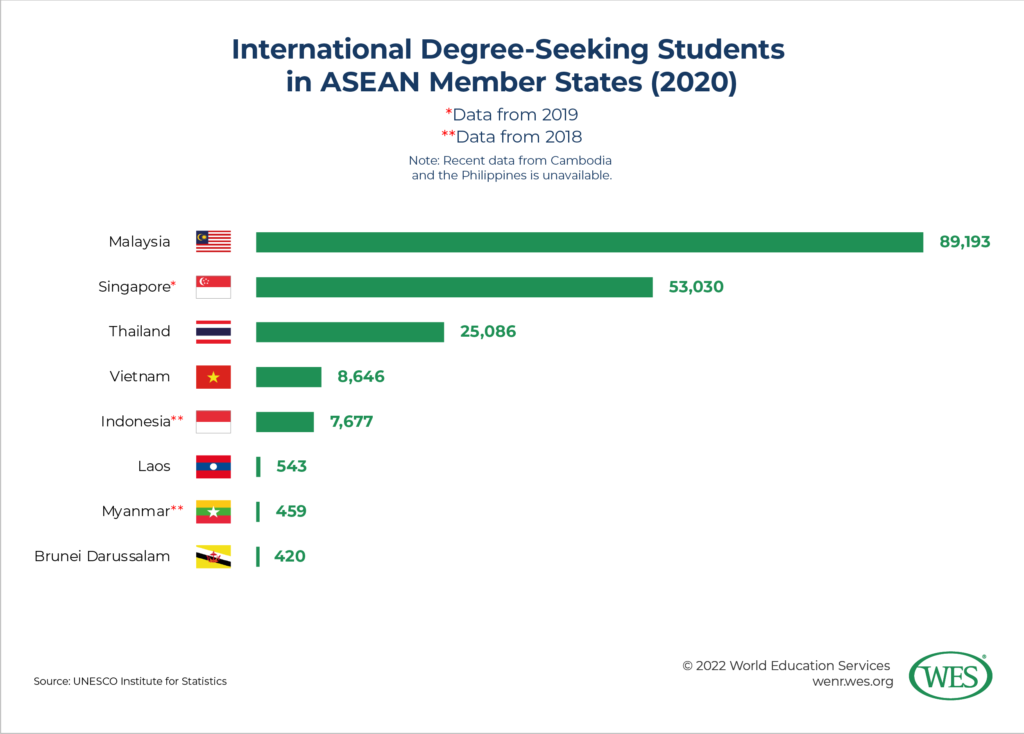

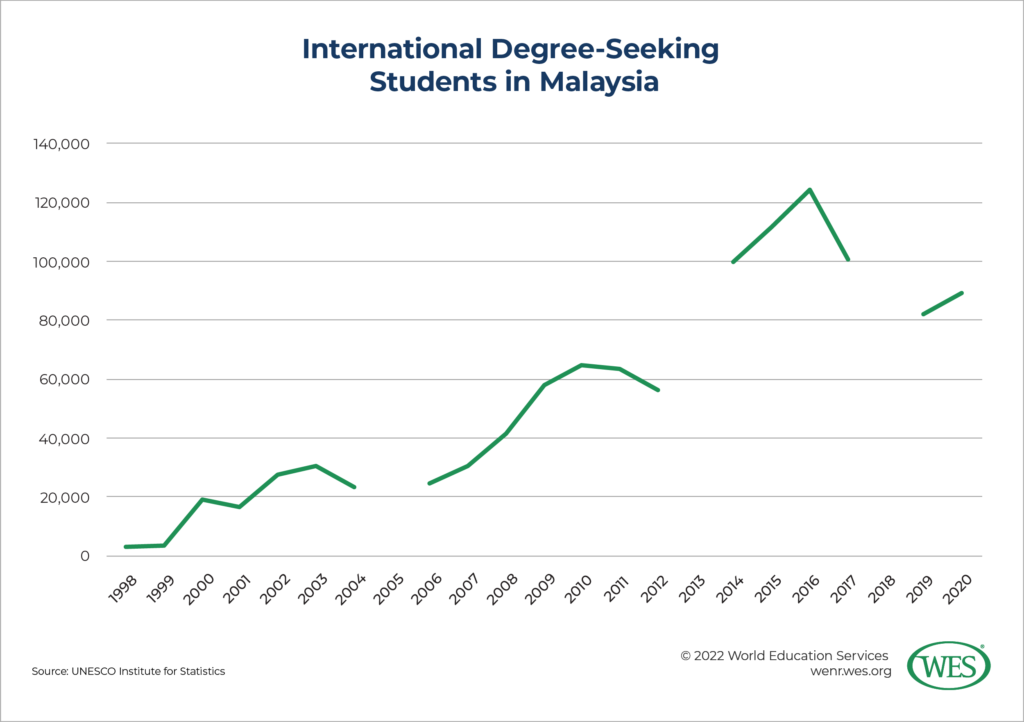

Malaysia welcomes far more international students than any other country in Southeast Asia. According to data from the UNESCO Institute of Statistics (UIS), in 2020 the country hosted 89,193 international degree-seeking students [17], while Singapore, the second most popular country in the region, welcomed just 54,982. That same year, Malaysia was the 13th-largest destination for international students in the world.

Malaysia’s popularity results in part from government policy. The Malaysian government has adopted aggressive measures aimed at internationalizing its higher education system, a process it hopes will improve the dynamism of the sector and make it more responsive to the demands of a knowledge-driven world economy. In 2012, the higher education ministry established Education Malaysia Global Services [19] (EMGS) to promote Malaysia as an international education hub and facilitate the movement of international students into the country.

In 2015, the ministry released the Malaysia Education Blueprint 2015-2025 (Higher Education), or MEB(HE) [20], an aspirational document that prioritizes the building of Malaysia’s education brand and turning the country into a globally recognized international education hub. The MEB(HE) sets an ambitious goal of attracting 250,000 international students to Malaysia’s schools and universities by 2025.

To achieve this, the MEB(HE) sketches a series of policy changes, such as simplifying the country’s immigration processes, creating multi-year student visas, and fast-tracking visa processing for international students recruited to consistently high-performing institutions.

Besides international students, Malaysia’s internationalization initiatives seek to attract scholarly expertise and institutional know-how from overseas. The MEB(HE) envisions the creation of pathways to facilitate the recruitment of top international scholars. In 2021, 1,688 [21] international scholars taught in private higher education institutions and 1,188 [22] taught at public universities.

The government has also worked to encourage universities overseas to establish branch campuses in Malaysia. Across the country, it has set up various education hubs [23], which are often subject to looser economic regulations to attract international providers. The most prominent of these, EduCity Iskandar [24], located in the southern part of the country, across the Straits of Johor from Singapore, hosts a handful of international branch campuses (IBCs).

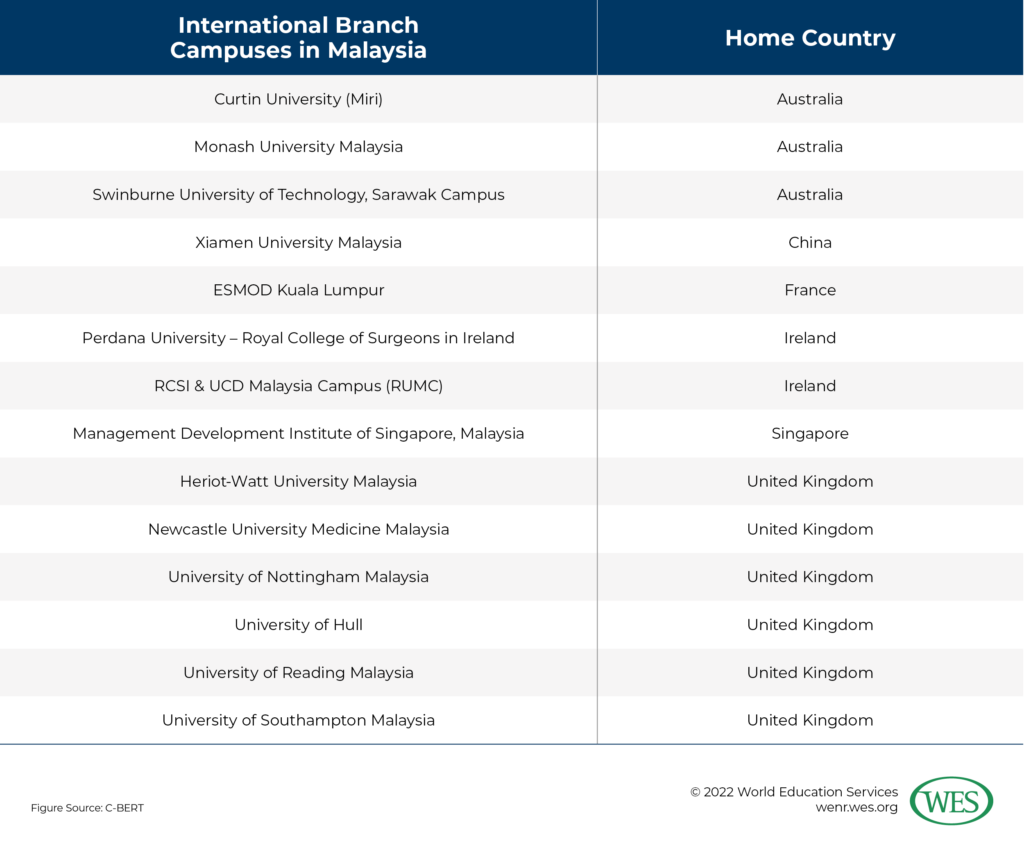

According to C-BERT [25] data, as of late 2020, 14 international universities had branch campuses in Malaysia, the fourth highest in the world, trailing only China (42), the United Arab Emirates (33), and Singapore (16).

As is the case with IBCs elsewhere, most of Malaysia’s IBCs are established by institutions based in western countries [26]. Five of Malaysia’s IBCs are from the United Kingdom, three from Australia, two from Ireland, and one from France. However, Malaysia also hosts the first IBC [27] of a public university in China, Xiamen University, Malaysia, as well as one from Singapore.

Tuition at IBCs is expensive, with some programs costing 25 times more5 [29] than similar offerings at a public university. Still, tuition at IBCs in Malaysia is lower than at the home campus overseas, allowing both Malaysian and international students to obtain a foreign qualification at a lower cost.

Domestic and international students can also earn international qualifications, frequently at even lower prices than at IBCs, by enrolling in one of a variety of transnational education [30] (TNE) programs. In partnership with universities overseas, Malaysian institutions offer various twinning, joint, and dual degrees, as well as franchise and validation programs, allowing students to pursue courses of study developed or overseen, at least in part, by international providers. Depending on the program, students earn degrees issued jointly by the international university and the Malaysian partner, or by the international university alone.

Transnational Education (TNE) Programs

Malaysia today is a hotspot [31] for TNE programs. TNE programs [30] involve cooperation between one or more international higher education institutions and one or more domestic partner institutions, which in Malaysia is typically a private provider.

Institutions based in the U.K. are the dominant players in Malaysian TNE programs. According to a 2020 report [32] from the U.K.’s Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (QAA), more than half of TNE programs in Malaysia involved a partnership with a U.K. institution. In 2020/21, 46,920 students [33] were studying for a U.K. higher education qualification from Malaysia, the second highest after China (60,495). Australia [34] and the United States are also major players [35] in Malaysian TNE, although comparable data are not available.

TNE arrangements between partner institutions tend to vary from program to program, their details codified in memoranda of understanding (MOU) agreed upon by all partners. These MOUs typically specify the roles and responsibilities of each institution, touching on topics that range from marketing, profit-sharing, and the setting of admissions standards, to teaching, student assessment, quality assurance, and degree-awarding authority.

Malaysian institutions offer many different types of TNE programs, most notably twinning, joint and dual degrees, and franchise and validation programs.

Twinning programs are articulation arrangements that allow students to take a year or two of courses in a Malaysian partner institution before transferring their credits to and completing their studies at an international partner institution. Examples include American Degree Transfer Programs [36] (ADTP), which are offered at a number of Malaysian and U.S. institutions. ADTPs allow students to pursue part of their studies in Malaysia and part in the U.S. Students completing a twinning program are awarded a degree issued by the international partner institution alone.

Depending on the program’s structure, twinning programs, which have existed in Malaysia since the late 1980s, are also frequently referred to as 2+1, 2+2, or 1+3 programs.

Joint and dual degree programs are collaborative arrangements offered by both the international university and the Malaysian partner institution. Students typically study at both institutions, often spending the first year or two at the Malaysian institution before moving overseas to complete their studies. Depending on the details of the arrangement, students completing the program are either awarded a single, joint degree, which bears the seal of both institutions, or two separate degrees issued by each partner institution individually.

In franchise programs, the international university authorizes the Malaysian partner to deliver one of the degree programs offered on its home campus. The international university typically designs the curriculum and learning materials, sets admission standards, assesses student performance, oversees the quality of the program, and awards the final degree. The partner institution is typically responsible for marketing, administrative processing, and teaching. The franchise arrangement is intended to guarantee that the program taught at the partner institution is essentially the same as that taught at the international university.

Validation [37] is a partnership arrangement with a division of operational responsibilities similar to that of franchise programs, and is often categorized [38] as a subdivision of the franchise program. However, the partner university is typically also responsible for assessing student performance, setting admissions standards, and, most significantly, developing the curriculum. The international university validates the quality of the academic program as equal to the standards of the program or programs offered at its home campus. For these programs, although the international university is responsible for the quality of the validated program, it does not offer the same program at its home campus.

For both franchise and validation programs, the authority to award the final degree always rests, by definition, with the international institution alone.

In Malaysia, institutions obtaining university status are barred [39] from offering franchise and validation programs, so private colleges and private university colleges are the only Malaysian partner institutions that offer these programs. If these partner institutions obtain full university status, they often rearrange existing franchise programs into joint or dual degree programs. Franchise and validation programs are also often referred to as 3+0 degree programs.

While these initiatives have helped increase international student enrollment in Malaysian universities, enrollment numbers have softened in recent years. The number of international students in Malaysia in 2020 was 28 percent lower than at its peak in 2016, when the country hosted 124,133 degree-seeking students.

This decline occurred almost entirely at private higher education institutions, which enroll the most (60 percent [41], in 2021) international students in Malaysia. According to data from Malaysia’s higher education ministry, international student enrollment at private higher education institutions declined from a peak of 103,198 [42], in 2017, to 58,063 [41], in 2021. From 2018 to 2019, alone, enrollment declined by more than a third, falling from 92,415 [43] to 59,013 [44].

This sharp decline followed the discovery [45] of a large human trafficking network involving some private higher education institutions and unscrupulous agents in Malaysia and abroad.

Human trafficking is a major problem in Malaysia, where many industries rely heavily on migrant workers. According to a September 2021 report [46], Malaysia’s 2 million documented migrant workers make up around 20 percent of the country’s workforce. They are joined by an estimated 4 million undocumented workers, who, the report suggests, may make up a majority of Malaysia’s overall workforce.

According to Freedom Collaborative [47], these migrant workers and undocumented workers in particular risk exploitation, including “passport confiscation, low pay in violation of minimum wage laws, salary deductions, poor living conditions, punishment by fines, high recruitment fees, debts to recruitment agencies and employers, forced labour, and human trafficking.”

Around 2013, unscrupulous recruitment agents began to exploit Malaysia’s student visa system. In many cases, they would trick students from countries overseas into paying exorbitant fees to enroll in fake Malaysian institutions. After arriving in Malaysia, duped students would find that their colleges held no classes, and that they were left with no prospects of completing their studies or recovering their money. Recruitment agents also often took and permanently withheld students’ passports on arrival. With Malaysia’s immigration regulations proscribing student visa holders from working, duped students were forced to work informally to survive.

Despite the gravity of the situation, it took years before authorities mounted an effective response. Beginning in 2015 [48], government officials started to revoke the authority of some private higher education institutions to recruit international students. Scrutiny intensified in the years that followed, as the government suspended [49] the international student recruitment licenses [50] of dozens of institutions unable to account for all of their international students.

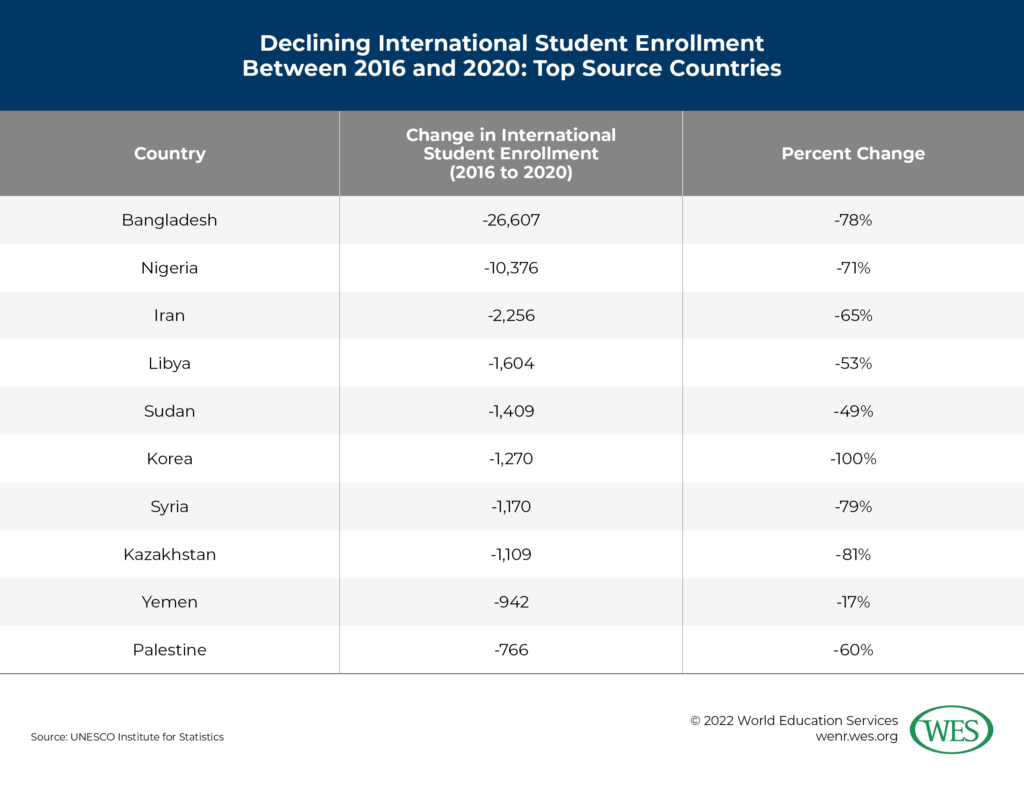

While no data on the number of international students exploited under these schemes exist, the impact of the government’s actions reveals the severity of the problem. Between 2012 and 2014, enrollment of Bangladeshi students, who bore the brunt of these scams, had grown more than 10-fold, rising from 2,033 [51] to 29,146. But as government scrutiny intensified from 2015 onwards, Bangladeshi enrollment collapsed. From a peak of 34,155 in 2016, enrollment has since declined by more than three quarters, falling to 7,548 in 2020.

A similar rise and fall occurred among Nigerian students, who, reports [53] suggest, were also trafficked to fake institutions in large numbers. Nigerian enrollment increased more than 230 percent between 2012 and 2016, when it peaked at 14,705. In the years since, the number of Nigerian students enrolled in Malaysian higher education institutions has declined by more than 71 percent, falling to 4,329 in 2020.

Although little information is available in English, these sharp declines suggest that government response has helped to reduce some of the risks faced by prospective international students.

Top Source Countries

Despite these risks, large numbers of Bangladeshi and Nigerian students continue to study in Malaysia today. These students are attracted to Malaysia by its reputation as a modern, cosmopolitan, and Muslim-friendly country.

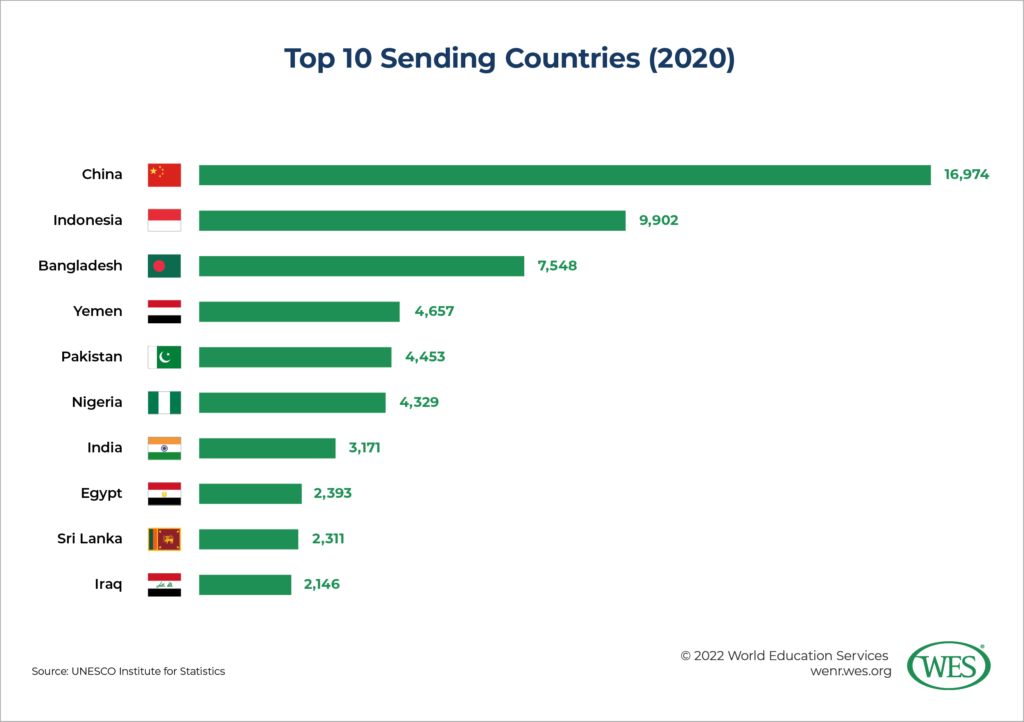

In fact, historically, most international students in Malaysia have come from other countries with large Muslim populations. The largest of these is Indonesia [54], Malaysia’s massive neighbor to the south. In 2020, Indonesia sent 9,902 international students to Malaysia, the second highest number that were sent that year.

Indonesian students are drawn to Malaysia by its geographic proximity, its cultural, religious, and linguistic similarities, and its relative affordability. Indonesian students also benefit from their country’s membership, alongside Malaysia, in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), established in late 2015 to increase economic collaboration among member states. The ASEAN Economy Community’s activities extend to the education sector [56], where it promotes various efforts to harmonize regional education systems and qualifications and spur intra-regional student mobility.

Despite Malaysia’s popularity among Muslim-majority nations, for the past few years China has been the largest sender of international students to Malaysia. In 2020, 16,974 Chinese students studied in Malaysian higher education institutions.

The ties between China and Malaysia are deep. China has been Malaysia’s largest trading partner for over a decade and, as noted above, a large percentage of Malaysia’s population traces its roots back to China and speaks Chinese at home and in school. Surveys [57] also find that Malaysia, alongside its neighbor Singapore, are outliers internationally when it comes to perceptions of China, with both having very positive views of China.

Malaysia’s unique higher education landscape also meets many of the needs of Chinese students. Malaysia’s numerous IBCs and private English-speaking universities are very attractive [58] study destinations for Chinese students, who continue to place a high value on Western education.

Geographic proximity to and friendly ties with China, as well as comparatively low tuition fees and living costs, make Malaysia a popular alternative to other countries with similar offerings, such as Australia. In fact, while Malaysia has been a popular destination for Chinese international students for decades, its standing has skyrocketed over the past few years. Data from Malaysia’s higher education ministry show that the number of Chinese students studying in Malaysia rose to 28,593 [41] in 2021, more than two-thirds higher than its level the previous year.

This increase may be coming at Australia’s expense [59], which has long been a top study destination for Chinese international students. Political tensions between China and Australia have intensified [60] in recent years, and at times Chinese international students have been caught in the cross fire. For example, following the outbreak of COVID-19, racist attacks [61] against Chinese people living in Australia rose dramatically. These incidents, and other diplomatic disputes, prompted China’s Ministry of Education to take the unusual step of warning [62] students headed to Australia that they may face the risk of racist violence and discrimination.

The impact of these tensions can be seen in international enrollment figures. According to UIS data, Chinese enrollment in Australian universities declined by 17.6 percent, a fall of 27,411 students, between 2019 and 2020. Over that same period, Chinese enrollment in Malaysian institutions rose dramatically, increasing by 5,261 students, or 44.9 percent.

While the top sending countries to Malaysia have remained stable for some time, the government does hope to recruit students from a greater variety of countries in the future. The MEB(HE) identifies diversifying Malaysia’s international student population as a priority, noting that it aims to target “top sending countries as well as strategic geographies for Malaysia.”

Outbound Student Mobility

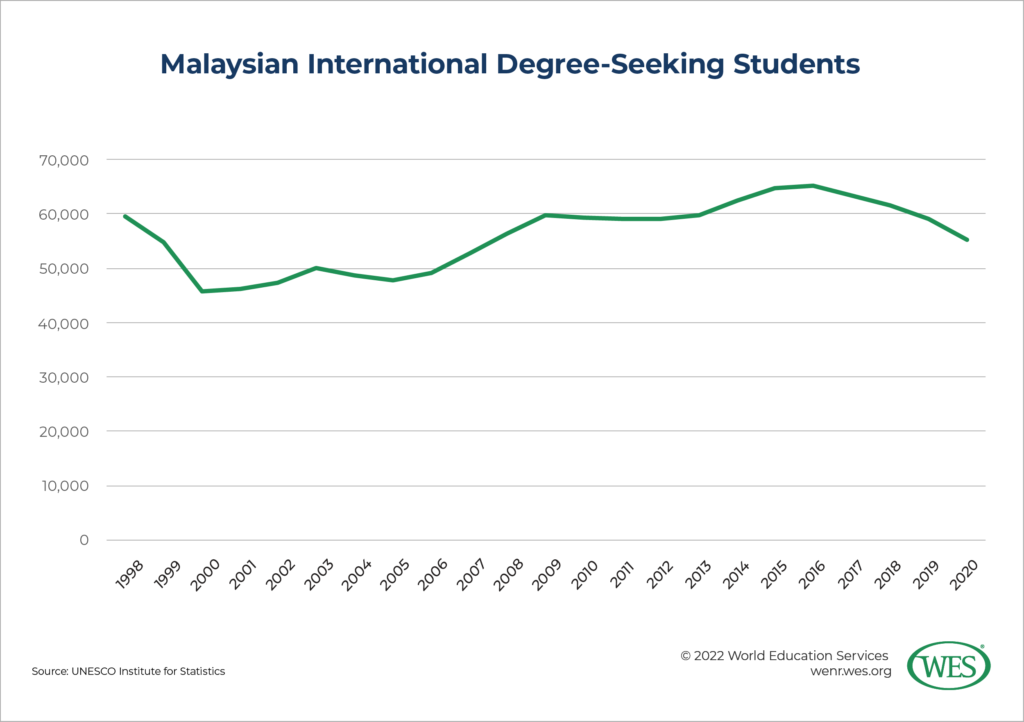

Malaysia sends relatively large numbers of students abroad. In 2020, Malaysia was the 19th-largest [63] source of international degree-seeking students. That year, its outbound mobility rate was 4.9 percent [64], higher than other upper middle-income countries (2.2 percent in 2019), although far lower than its smaller ASEAN neighbor Brunei (18 percent).

Over the years, Malaysian students have benefited from the availability of dozens of scholarships for overseas study funded by public and private organizations. For example, the Council of Trust for Indigenous People (Majlis Amanah Rakyat, or MARA [65]), a public enterprise under the Ministry of Rural Development (Kementerian Pembangunan Luar Bandar, KPLB [66]), offers scholarships [67] to high-achieving Bumiputera students. The Public Service Department (Jabatan Perkhidmatan Awam, JPA) also offers scholarships [68] to Malaysian students for undergraduate and postgraduate study in medical and STEM fields. Major Malaysian companies, such as Khazanah Nasional, Petronas, and Bank Negara, also fund [67] overseas studies, often reserving scholarships to students admitted to top ranked global institutions.

But in recent years, the government has changed course. The Malaysian government has shifted [69] its focus away from providing scholarships for international study to funding study at domestic universities. As a result, the number of Malaysian students studying internationally on scholarship has declined. In 2010 [70], 28,291 Malaysian students studying abroad were sponsored. Ten years later, 10,062 students [71] were sponsored, a bit more than a quarter (26.6 percent) of the 37,799 students for which current data were available.

This, combined with growing capacity and improving quality at Malaysia’s higher education institutions, may account for some of the recent decline in outbound student mobility. After peaking at 65,085 [63] in 2016, enrollment has declined 15 percent, falling to 55,311 in 2020, its lowest level since 2007.

The decline also coincides with a sharp fall [73] in the value of the Malaysian ringgit. Between August 2014 and October 2015, the ringgit lost more than a quarter of its value against the U.S. dollar. Much of the decline stemmed from a dramatic fall in the value of oil, one of Malaysia’s primary exports [74], although major government scandals [75] also likely played a part.

Top Destination Countries

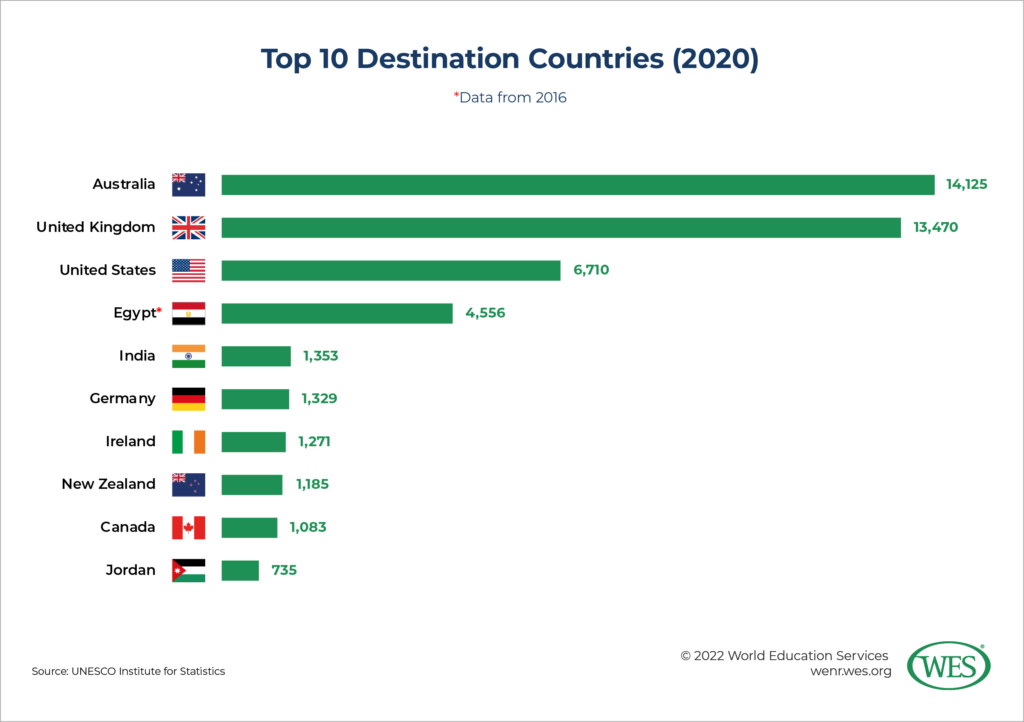

Most Malaysian international students head to Anglophone countries. Nearby Australia (14,125) and the U.K. (13,470) enrolled the most students in 2020.

Many Malaysian students choose to study in other Muslim-majority nations. In Egypt, large numbers of Malaysian students have long enrolled in the prestigious Although UIS does not provide updated figures on enrollment in Egypt, data from Malaysia’s higher education ministry show that 8,355 Malaysian students [71] enrolled in Egypt in 2020, nearly all of them self-sponsored. Jordan is also popular with Malaysian students, enrolling 735 in 2020. These countries are popular destinations for Malaysian students hoping to study the Arabic language and Islamic religious studies, as well as medicine and dentistry.

Although comparable UIS data are again unavailable, sizable numbers of Malaysian students enroll in Chinese universities as well. According to statistics from Malaysia’s higher education ministry, 11,920 Malaysian students were enrolled in Chinese higher education institutions in 2021. Among all countries, China welcomes the highest number of sponsored Malaysian students. In 2020, 3,820 Malaysian students in China were sponsored, compared with just 953 who were self-sponsored.

The United States and Canada

Although the U.S. is one of the most popular destinations for Malaysian international students, enrollment has declined steeply since the 2017/18 academic year. Since then, enrollment has declined 40.4 percent, falling to 4,933 in 2021/22, according to IIE Open Doors [77] data.

While the fall in the value of the ringgit likely accounts for much of this decline, the victory of Donald J. Trump in the 2016 U.S. presidential election may also have played a role. Not only is it likely that Trump’s nativist rhetoric alienated Malaysia’s large Muslim population, it also probably impacted the decision-making of Chinese Malaysians. According to EducationUSA’s 2018 Global Guide [78], the latter group constitute a majority of the Malaysian students in the U.S.

The scaling back of scholarships may also have played a role. The number of Malaysian international students in the U.S. on scholarships has fluctuated over the years, declining from 2,197 in 2015 [79] to 532 in 2019 [80] and 826 in 2020 [71].

Much of this decline occurred at the undergraduate level [82]. Undergraduate enrollment fell from 5,817, or 70.3 percent of all enrollments, in 2017/18 to 2,670, or 54.1 percent, in 2021/22. Over that same period, the share of Malaysian students enrolled in graduate programs grew from 13.5 percent to 20.9 percent, while the share participating in Optional Practical Training (OPT) grew from 14.8 percent to 24.0 percent. Non-degree programs, never a major draw for Malaysian students, declined from 115 (or 1.4 percent) to 44 (or 1.0 percent) over the same period.

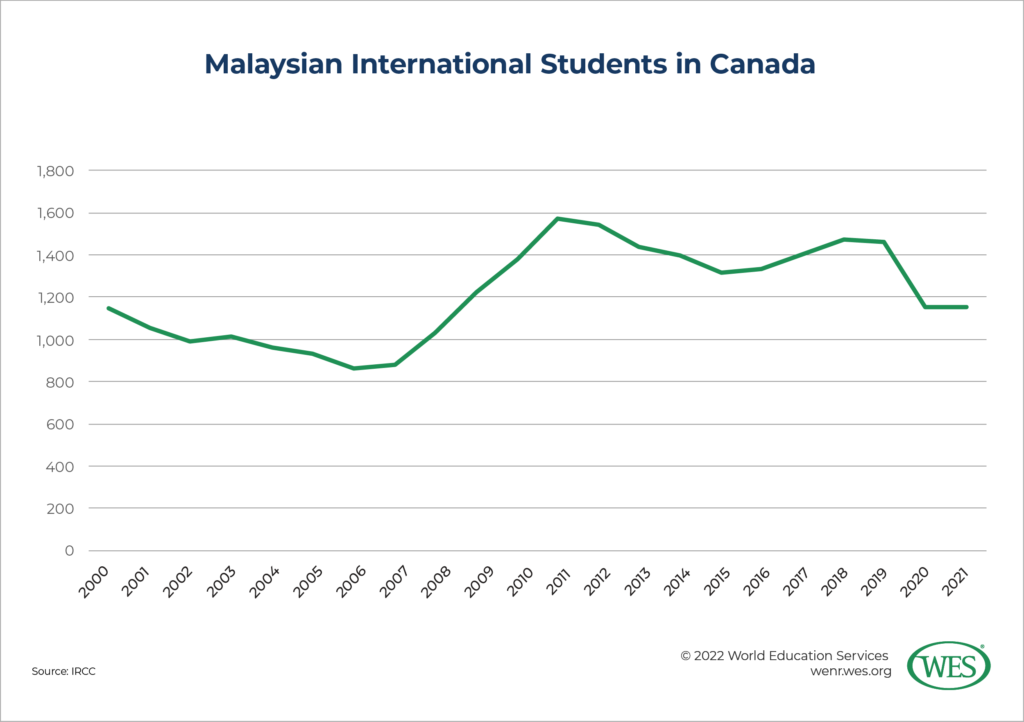

In Canada, steep declines only occurred with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Between 2019 and 2020, enrollment fell 20.9 percent [83] to 1,155, although it stabilized quickly. The following year, 1,150 Malaysian students studied in Canada.

In recent years, Canada has adopted friendlier policies toward international students and immigrants, making the country a more attractive study destination than the U.S. for many prospective students. The Malaysian ringgit likely also goes further in Canada than it does in the U.S. Between late July 2014 and early October 2015, the ringgit declined only 13.7 percent [85] against the Canadian dollar, compared with a decline of 28.2 percent against the U.S. dollar.

The Education System of Malaysia

Prior to the arrival of the British, formal education in Malaysia was religious in nature. A small number of young men attended residential schools, known as sekolah pondok,6 [86] literally hut or cottage schools, where they studied Islamic ethics and doctrine, and read and memorized religious texts.

Following their arrival in the late nineteenth century, British colonial administrators set about founding schools modeled on those in the British Isles. However, the school system they established in Malaysia was deeply fragmented. British officials set up separate vernacular schools for each of Malaysia’s major ethnic groups, creating an ethnic educational divide that continues to this day.

Each vernacular school taught in a different language, either Bahasa Melayu, Chinese,7 [87] or Tamil. Each also offered a different program of study. For example, the curriculum at Malay vernacular schools included Islamic studies and vocational training, while those at Chinese and Tamil schools taught the history, culture, and geography of China and India, respectively. According to scholars, the distinct curricula used by each type of vernacular school prepared students for very different futures, helping to create and perpetuate occupational and social disparities among ethnicities.

Besides vernacular schools, the British also set up English-medium schools, which again followed a unique curriculum. In theory, these prestigious schools were open to all ethnicities. But in practice, only the urban elite attended these schools, which were established exclusively in major cities. Given Malaysia’s geographic and economic compartmentalization, this meant that Malays and other Bumiputera were underrepresented at these schools. For example, in 1937, ethnic Chinese students made up half of all students attending English-medium schools in the Federated Malay States (modern-day Selangor, Perak, Pahang, and Negeri Sembilan), while Malays made up just 15 percent.8 [88]

The inadequacies of this arrangement were readily apparent at independence in 1957, and the country’s new policymakers viewed education as an important means of nation-building. To bring the multicultural nation together, they moved to unify the country’s education system.

Ambitious plans were developed that would standardize the curriculum and mandate the use of Bahasa Melayu and English in all schools across the nation. But these plans were quickly abandoned in the face of opposition from ethnic minority communities, who viewed the proposals with suspicion.

A compromise position, outlined in the 1956 Razak Report and incorporated into the Education Act 1961, was eventually adopted. Under this system, two parallel systems of elementary education would operate side-by-side: a national school system that used Bahasa Melayu as the medium of instruction, and national-type, or vernacular, school system, using either Mandarin Chinese, Tamil, or English. Although teaching in different languages, both national and national-type elementary schools would be united by a common curriculum. At the secondary level, teaching would continue in English, as it had during the colonial period, although Bahasa Melayu would be made a compulsory language.

The events of 1969 prompted further changes. As noted above, the unrest propelled leaders to power who believed that easing ethnic tensions in the country required that the central government adopt policies favoring Malays and other Bumiputera.

The Malaysian government adopted preferential education policies, establishing schools, scholarships, and universities available only to Malay or other Bumiputera students.

The government also mandated the use of Bahasa Melayu as the language of instruction at public secondary schools. Although vernacular elementary schools remained, all students would attend national secondary schools, where Bahasa Melayu would be the language of instruction. Between 1970 and 1982, the government gradually converted all English-medium elementary and secondary schools to national Malay-medium schools.

As Malaysia began to industrialize its economy in the 1980s, economic considerations began to influence educational policy. New curricula were introduced at the elementary and secondary levels, and new national examinations were developed to track student performance.

Still, ethnic concerns were important. In 1989, the education ministry adopted the National Philosophy of Education [89] (Falsafah Pendidikan Kebangsaan), which aims to produce Malaysian citizens who are “intellectually, spiritually, emotionally, and physically balanced and harmonious” and who “contribute to the harmony and betterment of the family, the society, and the nation at large.” The National Philosophy of Education continues to guide education policy in Malaysia to the present day.

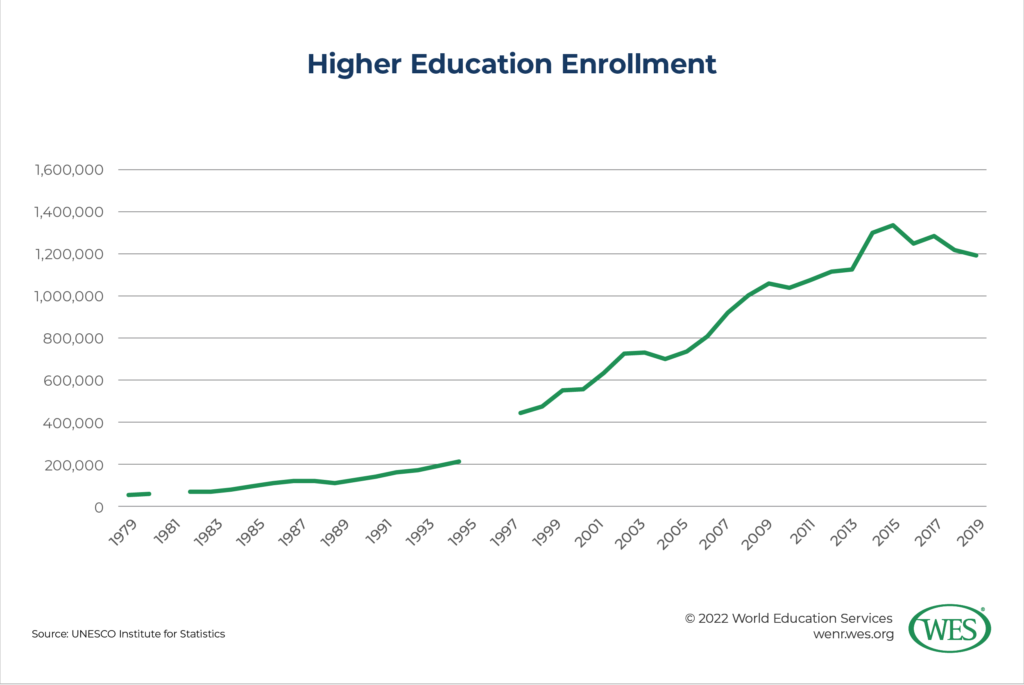

Malaysia’s rapid economic development since the 1990s prompted new priorities for the education system. To develop a workforce with the knowledge and skills needed to staff new enterprises, the government moved to expand the higher education system. In the mid-1990s, the government legalized the establishment of private higher education institutions, a move that prompted rapid growth in higher education enrollment.

But while policymakers succeeded in increasing enrollment, they have had less success improving educational quality. Malaysia’s performance on international assessments, such as the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) and the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), has long trailed that of comparable countries.

Student outcomes even declined during the first decade of the twenty-first century. UNESCO’s EFA global monitoring report, 2013-2014 [90] noted that:

“Malaysia witnessed the largest decline in test scores of all countries participating in TIMSS over the decade. In 2003, the vast majority of adolescents passed the minimum benchmark in Malaysia, whether rich or poor. However, standards appear to have declined substantially over the decade, particularly for the poorest boys, only around half of whom reached the minimum benchmark in 2011, compared with over 90% in 2003. Poorest boys moved from being similar to average performers in the United States to similar to those in Botswana.”

Malaysia’s poor performance on international assessments prompted yet another round of major reforms. Around 2010, the Ministry of Education developed new elementary and secondary curricula, replacing those developed in the 1980s, which it hoped would provide students with the skills and expertise needed to succeed in the global knowledge economy.

The government also adopted ambitious Education Blueprints to guide education policy over the coming decades. These focused on increasing the efficiency of the school system; however, despite devoting a comparatively large proportion of government spending to education, schooling in Malaysia, as measured by learning outcomes, underperforms.

Education officials also advanced plans to decentralize the education system, which is one of the world’s most centralized. Beginning around 2010, schools and universities were granted additional control over curricular development, administrative practices, and assessment techniques.

Policymakers hope these reforms will make a difference. Since independence, Malaysia’s education system has achieved notable success expanding access to education and improving basic literacy. For example, the secondary gross enrollment ratio [91] (GER) grew from 39.2 percent in 1970 to 82.5 percent in 2020, while adult literacy rates [92] have increased from 70 percent in 1980 to 95 percent in 2019. And the government spends a significant amount of money on education, allowing many students to access free public elementary and secondary education, and highly subsidized higher education.

But, with Malaysia’s economy continuing to expand, improving the quality of education accessible to Malaysian students of all ethnicities will be essential to the country’s navigating its projected transition to a high-income country [16] by the end of the decade.

Administration of the Education System

The British political system strongly influenced that of Malaysia. Like the U.K., Malaysia is a constitutional monarchy and parliamentary democracy. However, in Malaysia, the monarchy is elective: every five years, traditional rulers from nine Malaysian states gather to elect from among themselves a Yang di-Pertuan Agong, or Supreme King of Malaysia. Despite the title, the role of the Yang di-Pertuan Agong is largely symbolic. Executive power rests almost exclusively in the office of the prime minister.

Although technically a federal state, most political power, as well as government revenue, rests with the federal government. Malaysia’s 13 states (negeri) and three federal territories (wilayah persekutuan) exercise only limited authority.

A similar concentration of authority characterizes the administration of Malaysia’s education system. A 2013 World Bank report [93] identified Malaysia’s education system as one of most heavily centralized in the world.

Since 2020 [94], two ministries have been responsible for education across the country: the Ministry of Education (Kementerian Pendidikan, MOE [95]) and the Ministry of Higher Education (Kementerian Pengajian Tinggi, MoHE [96]).9 [97]

The MOE oversees education at the preschool, elementary, secondary, post-secondary, and teacher-training levels at both public and private institutions. At these levels, the MOE’s responsibilities include strategic planning, policy development, quality assurance, funding, and staff recruitment, among others.

A handful of public agencies under the MOE assume more specialized responsibilities. For example, the Examination Syndicate (Lembaga Peperiksaan, LP [98]) and the Malaysian Examinations Council (Majlis Peperiksaan Malaysia, MPM) prepare and administer major national examinations, while the MOE’s Curriculum Development Division [99] designs national textbooks.

The MoHE [100] oversees higher education at both public and private providers, such as public universities, polytechnics, and community colleges, and a variety of private higher education institutions. Despite attempts to expand institutional autonomy, the MoHE still retains tight control over public institutions. At public universities, the MoHE even appoints vice chancellors, the highest level of university official.

With rare exceptions, both public and private higher education institutions are subject to quality control by the Malaysian Qualifications Agency [101] (MQA), an MoHE agency. Since 2007, when it replaced the National Accreditation Board (Lembaga Akreditasi Negara, LAN), the MQA has been responsible for overall quality assurance in Malaysian higher education and for the accreditation of all higher education programs. The MQA maintains the Malaysian Qualifications Register [102] (MQR), where it records the accreditation status of qualifications offered by both public and private institutions.

The National Higher Education Fund Corporation (Perbadanan Tabung Pendidikan Tinggi Nasional, PTPTN [103]), also under the MoHE, is responsible for managing student loans at the higher education level. The PTPTN is by far the largest provider of loans to students studying at Malaysia’s public and private higher education institutions.

Other government ministries and agencies play more minor roles in administering the education system. For example, the Department of Skills Development [104] (Jabatan Pembangunan Kemahiran, JPK) which is under the Ministry of Human Resources [105] (Kementerian Sumber Manusia, KSM) oversees skills qualifications. National and state religious departments also play an important role in the management of religious schools at the preschool, elementary, and secondary levels.

To increase the ability of the education sector to respond to changing economic conditions, the government has taken some steps to decentralize parts of the education system. In 1982, district education offices were created, although their role is largely supervisory. More recently, the MOE has devolved a limited degree of autonomy over financial management and implementation of the curriculum to certain high performing schools.10 [106]

Other initiatives have worked to decentralize the assessment of student performance. These initiatives intensified in recent years, as the government moved to eliminate major national examinations formerly conducted at the end of elementary and lower secondary school. These national assessments will be replaced with school-based assessments (Pentaksiran Berasaskan Sekolah, PBS), which, while referring to established national standards, are developed, administered, and graded by local schools.

Language of Instruction and Academic Year

Language policy in Malaysia is fiercely contested, especially in education. On multiple occasions since independence, Malaysia’s three major ethnic communities have mobilized to defend their right to teach and learn in their own languages.

Today, Malaysia’s elementary school system is multilingual. National schools teach in Malay, while vernacular, or national-type, schools teach in Mandarin Chinese or Tamil.

At the secondary level, the public school system is monolingual. Secondary schools teach in Bahasa Melayu to students of all ethnicities, although elective courses in Chinese and Tamil, as well as other foreign languages, such as French or German, are available at some schools.

However, some private secondary schools do teach in languages other than Bahasa Melayu. For example, Independent Chinese secondary schools teach in Mandarin Chinese, and international high schools, which Malaysian citizens have been able to attend since 2006 [107], frequently teach in English.

English has been growing in prominence in recent years at all levels of the education system. English is taught as a mandatory subject beginning in elementary school, and, in 2016, the MOE introduced the Dual Language Program (Program Dwibahasa, DLP), which gives schools the option of using English to teach science and mathematics subjects.

At the higher education level, Bahasa Melayu has been used in all undergraduate courses at public universities since 1983, although students today are required to take the Malaysian University English Test (MUET) to be admitted to public universities. At the postgraduate and doctoral level, public universities typically teach in English. Private higher education institutions typically teach in English at all levels.

The elementary and secondary school year is divided into two semesters, the first extending from January to late May, the second from early July to November.

The academic year at the university level begins at the end of February or the beginning of March and ends in October. It typically consists of three semesters, each lasting 12 weeks. Over the break from November to February, some institutions also offer weekend courses, allowing students to complete their programs more quickly.

Early Childhood Education

Preschool education [108] (pendidikan prasekolah) in Malaysia lasts two years, from age 4 to age 6 [109]. It is not compulsory, although most families do elect to send their children to preschool. In 2021, Malaysia’s pre-elementary gross enrollment ratio (GER) was 87.5 percent [110] and 912,564 students [111] were enrolled in preschool programs. These numbers are down significantly from their levels at the start of the pandemic. In 2020, 98.1 percent of the eligible age group, or 997,968 children, were enrolled in Malaysian preschools.

As a result of Malaysia’s unique history, a variety of different institutions offer preschool programs.

In the 1970s, the Department of Community Development (Jabatan Kemajuan Masyarakat, KEMAS [112]) under the Ministry of Rural Development (Kementerian Pembangunan Luar Bandar, KPLB [66]) established the country’s first public preschools [113], known as Tabika KEMAS, in rural and semi-rural areas of Malaysia. In 2022 [114], these preschools enrolled 206,642 students.

Later in 1970s, the Ministry of National Unity [115] (Kementerian Perpaduan Negara) also began to establish public preschools in some urban neighborhoods. Known as Tabika Perpaduan [116], or Unity kindergartens, these schools aim to enroll children from all ethnicities. In 2022, Perpaduan preschools enrolled 36,957 students.

In the 1980s, private preschools began to proliferate, educating the children of both Malaysians and non-Malaysians. In 2022, 269,260 students were enrolled in private preschools. Since independence, private and public religious agencies, such as the Selangor Islamic Religious Department (Jabatan Agama Islam Selangor, JAIS), have also opened networks of preschools throughout the country.

The MOE only really became involved in preschool education in the 1990s, when it began to establish public preschools as annexes to existing elementary schools. Known as MOE preschools, these institutions aim at providing education to low-income families living outside of the urban core. In 2022, MOE preschools enrolled 206,346 students.

As a result of this institutional diversity, several different government ministries oversee preschool education, the most important of which are the Ministry of National Unity, KPLB, and MOE. Despite this administrative fragmentation, all preschools, both public and private, must follow the National Preschool Standard Curriculum (Kurikulum Standard Prasekolah Kebangsaan, KSPK).

For children under the age of 4, a network of public and private nursery schools also provides childcare and educational services. These institutions are administered by the Department of Social Welfare (Jabatan Kebajikan Masyarakat, JKM [117]) at the Ministry of Women, Family and Community Development (Kementerian Pembangunan Wanita, Keluarga dan Masyarakat, KPWKM [118]).

Elementary Education

Elementary education [119] lasts six years, from the age of 7 to the age of 12, extending from Year (Tahun) 1, or Standard (Darjah) 1, to Year 6, or Standard 6 (equivalent to grades 1 through 6). It has been compulsory [120] since 2003, and enrollment at public schools is free and open [121] to all children residing in Malaysia.

Elementary enrollment is nearly universal. According to UIS data, Malaysia’s elementary gross enrollment ratio (GER) was 103.9 [91] percent in 2020, with around 3.1 million [111] students enrolled at the elementary level.

Still, despite success expanding elementary education to nearly all eligible students, learning outcomes have struggled to improve, as mentioned above. Shockingly, Malaysia’s scores on the TIMSS, which measures student performance in mathematics and science at grades 4 and 8, even declined between 2003 and 2011.

Poor international assessment results helped prompt a re-evaluation of the curricula used at Malaysia’s schools. At the elementary level, a new curriculum, the National School Standard Curriculum (Kurikulum Standard Sekolah Randah, KSSR), was gradually introduced between 2011 and 2016. The KSSR replaced the Integrated Primary School Curriculum (Kurikulum Bersepadu Sekolah Rendah, KBSR) which was first introduced in 1983.

The KSSR Framework [122] was developed around six pillars: communication, spiritual attitudes and values, humanities, personal competence, physical development and aesthetics, and science and technology. Its focus reflects the Malaysian government’s interest in economic development, with content aimed at providing the skills needed for success in the twenty-first-century world.

The KSSR curriculum includes both core and elective courses. Core courses are compulsory and include [123] Bahasa Melayu, English language, design and technology, history, Islamic education (for Muslim students) or moral education (for non-Muslim students), mathematics, music, physical and health education, science, and visual arts. Chinese or Tamil language is also compulsory for students in national-type schools—these can also be taken as electives at some national schools. Some elementary schools also offer other languages, such as Arabic, Iban, Kadazandusun, and Semai, as elective options.

Until 2021, students completing the elementary cycle took the Primary School Achievement Test (Ujian Penilaian Sekolah Rendah, UPSR). The UPSR tested students on Bahasa Melayu, English, mathematics, and science. The test was largely diagnostic—regardless of performance, all students taking the UPSR and completing elementary school were automatically promoted to secondary school.

But in 2021, the MOE announced [124] that it was abolishing the UPSR, replacing it with school-based assessments (Pentaksiran Berasaskan Sekolah, PBS) alone.

Students in national-type Chinese and Tamil schools are required to meet a minimum level of proficiency in Bahasa Melayu subjects to continue to national secondary schools. Beginning in 2022 [125], those unable to do so must sit for the Bahasa Melayu Assessment Literacy Test (Ujian Pengesanan Literasi Bahasa Melayu, UPLBM). Those failing the UPLBM take a one-year transition class (Kelas Peralihan) to improve their knowledge of Bahasa Melayu before entering secondary school.

National and National-Type Schools

At the elementary level, Malaysian students can study in a variety of schools, including private academic schools, international schools, and private and public religious schools.

But most students study in either national (sekolah kebangsaan, SK) or national-type schools. The latter, also known as vernacular schools, include national-type Chinese schools (Sekolah Jenis Kebangsaan Cina, SJKC) and national-type Tamil schools (Sekolah Jenis Kebangsaan Tamil, SJKT). As noted above, the roots of this division extend into the colonial period.

Students at all national and national-type schools follow the KSSR curriculum, although the language of instruction varies. National schools teach in Bahasa Melayu, while national-type schools teach in either Mandarin Chinese or Tamil. National schools and national-type schools are open to students of any ethnicity.

While national schools are fully funded by the government, national-type schools receive more limited public aid. At these schools, the government only funds operating expenses and teacher and administrative staff salaries. Capital expenses, such as for infrastructure improvements and facilities maintenance, must be funded by private contributions.

To enhance national unity, the Malaysian government has long attempted to promote enrollment in national schools among all Malaysians. The Malaysia Education Blueprint 2013-2025 (Preschool to Post-Secondary Education) [126], or MEB, notes that the “ultimate objective is for the national schools to be the school of choice such that interactions between students of different socioeconomic, religious, and ethnic backgrounds naturally occur in school.”

Still, national schools have struggled to attract non-Malay students. Although national schools enroll the vast majority of all Malaysian elementary school students—around 2.2 million [127] students were enrolled in 5,868 national schools in June, 2022—ethnic minorities make up a very small percentage of enrolled students.

In 2020 [128], Chinese and Indian students composed just .7 percent and 2.6 percent of all students enrolled in Malaysian national schools, respectively. Those percentages actually declined from a decade before, when Chinese and Tamil students made up around 1.2 percent and 3.2 percent, respectively, of all national school students.

The difficulties national schools face in attracting non-Malay students stem in part from a widely shared perception that national schools favor Malays and Muslims. Incidents of discrimination encountered by non-Malay and non-Muslim students at national schools, accounts of which surface from time to time in the media, reinforce this perception. Concerns about the ethnic composition of the teachers and administrators at national schools have a similar effect. From the leadership of the MOE down to the teachers at local schools, national school staff are overwhelmingly ethnic Malay.

Instead, students from ethnic minorities have long elected to enroll in national-type schools. Until recently, this meant that national-type schools remained ethnically homogeneous, despite being open to all ethnicities.

But in recent years, the situation has changed significantly at Chinese national-type schools. While these schools continue to attract large numbers of ethnic Chinese students—according to the MEB 2013-2025, 96 percent of all ethnic Chinese students were enrolled in SJKTs in 2011—they have also begun to attract more and more non-Chinese students.

In 2020, Malay students made up 15.3 percent of all students enrolled in Chinese vernacular schools, up from 9.5 percent in 2010. Over the same period, the proportion of ethnic Indian students increased from around 1.7 percent to 2.8 percent. As a result, Chinese national-type schools are Malaysia’s most ethnically diverse elementary schools.

Growing non-Chinese enrollment stems in part from the widely held belief that the quality of education at Chinese vernacular schools is superior to that at national schools. While the government does not fund Chinese national-type schools at the same level that it funds national schools, private contributions from Malaysia’s ethnic Chinese community more than make up the difference.

Still, despite their popularity, total enrollment in Chinese national-type schools has declined significantly over the past decade. In June 2022, 495,386 students were enrolled in 1,302 national-type Chinese schools, down from 598,488 [129] students in 2011.

Declining birthrates may be driving this trend. Between 2010 and 2021, Malaysia’s elementary school-age population shrank from 3.2 million [130] to 3.0 million. This demographic contraction is strongest among Chinese Malaysians [131], whose birthrates are low and emigration rates high.

The situation at national-type Tamil schools differs dramatically from that at Chinese vernacular schools. While Tamil vernacular schools are attended almost entirely by ethnic Indian students, a large percentage of Indian parents choose to send their students to either national or Chinese vernacular schools. According to the MEB 2013-2025, 38 percent of Indian students were enrolled in national schools and 6 percent in Chinese vernacular schools in 2011.

While private contributions make up for lower levels of government funding at Chinese vernacular schools, the same is typically not true at Tamil vernacular schools. Many of these schools were initially established on and run by rubber plantations located in rural areas. Over the years, many estate owners, who once were responsible for funding these schools, have failed to invest in their upkeep. Also, ethnic Tamil communities are often less well-off than their ethnic Chinese counterparts, making it difficult to close the gap between what the government pays and what schools need for basic capital expenses. Finally, many ethnic Indians have moved from rural towns to major cities, where few Tamil vernacular schools have been established.

According to MOE statistics, 79,309 students were enrolled in 528 Tamil vernacular schools in June 2022, down from 102,642 in 2011. In 2011, according to the MEB, 99 percent of all students enrolled in these schools were ethnic Indians.

Lower Secondary Education (Pendidikan Menengah Rendah)

Secondary education is divided [132] into two stages: lower secondary and upper secondary. Lower secondary education lasts three years, from ages 13 to 15. It consists of three grades, or Forms (Tingkatan), from Form 1 to Form 3 (equivalent to grades 7 to 9).

Enrollment at the secondary level is not compulsory. According to UIS data, Malaysia’s lower secondary GER was 92.5 percent [91] in 2021. That year, around 1.4 million students [111] were enrolled in lower secondary school.

Unlike elementary education, public secondary education, at both the lower and upper levels, is monolingual: All teaching is conducted in Bahasa Melayu.

Secondary schools follow a national secondary curriculum, the Secondary School Standard Curriculum (Kurikulum Standard Sekolah Menengah, KSSM), which was introduced in 2017. The KSSM replaced the Integrated Secondary School Curriculum (Kurikulum Bersepadu Sekolah Menengah, KBSM), which was first introduced in 1989.

The KSSM aligns with the KSSR, the curriculum recently introduced at the elementary level. Like that curriculum, the KSSM also aims to prepare students with the skills and competencies needed to succeed in the twenty-first century.

Until 2022, students took a national assessment test, the Form Three Assessment (Pentaksiran Tingkatan Tiga, PT3 [133]), at the end of lower secondary school. The PT3 replaced the earlier Lower Secondary Examination (Penilaian Menengah Rendah, PMR) in 2014.

The PT3 examination [134] combined elements of centralized and local control. It was administered by a local school but guided by standards developed and provided by the central Examination Board. It utilized written, oral, and other testing methods to evaluate students on seven or more subjects.

Regardless of their performance on the PT3, students were able to enter upper secondary school. However, PT3 performance strongly influenced students’ future educational trajectories. School officials used PT3 test scores to determine admissions to the various streams available at the upper secondary school level. After upper secondary, these streams themselves help determine admission to different pre-university, and, eventually, university programs.

But in 2022 [135], the MOE abolished the PT3. As was the case with the UPSR, the PT3 will be replaced with school-based assessments (PBS) alone.

Upper Secondary Education (Pendidikan Menengah Atas)

Upper secondary education lasts two years, ages 16 and 17, and consists of Forms 4 and 5 (equivalent to grades 10 and 11). According to UIS data, in 2021, Malaysia’s upper secondary GER was 76.7 percent [91], with about 1.2 million [111] students enrolled at the upper secondary level.

In general, upper secondary school is divided into three tracks [136]: general academic (akademik biasa), technical and vocational (teknik dan vokasional), and religion (agama).

General Academic (akademik biasa)

Until 2020, students in the general academic track were streamed [137] into either science or humanities tracks, depending on both their interests and their performance on the PT3.

However, beginning in 2020, the MOE replaced these streams with a system of subject packages [138]. There are two principal subject packages: science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (sains, teknologi, kejuruteraan, dan matematik, STEM) and literature and humanities (sastera dan kemanusiaan). Although the two principal subject packages resemble the previous science and humanities tracks, the subject package system offers students greater flexibility in choosing their own course of study.

Students in the STEM subject package can choose courses from three groups of electives: pure science and mathematics, applied science and technology, and vocational subjects.

The first elective group, pure science and mathematics, includes four subjects: biology, chemistry, mathematics, and physics. The applied science and technology group includes 12 subjects, such as agriculture, computer science, and engineering. The vocational group includes 22 subjects, such as construction, interior design, graphic design, and plumbing.

Students who choose the literature and humanities subject package can also choose among three elective groups: languages, Islamic studies, and humanities and literature. The languages group includes 11 subjects, the humanities and literature group includes 11 subjects, and the Islamic studies group includes 13 subjects.

Students in both subject packages are still required to take a similar set of core and compulsory courses: Bahasa Melayu, English language, mathematics, science, history, Islamic or moral education, and physical and health education.

Since the elimination of the PT3, admission to either the STEM or humanities subject package is determined [139] through an evaluation of multiple factors, including teacher recommendations, student interest, and previous performance in science and mathematics subjects.

Technical (Teknikal)

Students interested in technical or vocational fields can choose from several upper secondary options. Students performing well in lower secondary mathematics and science subjects can enroll in the two-year technical stream [140] offered at a handful of technical secondary schools (sekolah menengah teknik, SMT). Students in this stream study and train in the fields [141] of agriculture, commerce, civil engineering, electrical and electronic engineering, and mechanical engineering.

Students can also enroll in the Upper Secondary Industrial Apprenticeship (Perantisan Industri Menengah Atas, PIMA) program, which is designed for students struggling academically. PIMA students spend just two days [142] a week in the classroom. During the rest of the week, they participate in an industry apprenticeship.

Another vocational option, the Upper Secondary Vocational Education program (Program Vokasional Menengah Atas, PVMA [143]), requires two years of study and training, at the end of which successful students earn both a Malaysian Certificate of Education and a Level 2 Malaysian Skills Certificate.

Note also that students completing elementary education can enroll [144] in three-year Basic Vocational Education (Pendidikan Asas Vokasional, PAV [145]) programs offered at some public schools.

Religion (Agama)

Students can also enroll in religious secondary schools. A variety of different types of religious schools exists, including Government-Aided Religious Schools [146] (Sekolah Agama Bantuan Kerajaan, SABK) and National Religious Secondary Schools [147] (Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Agama, SMKA).

Students at these schools study Arabic and the Jawi script, an alternative writing system used for Bahasa Melayu that is based on Arabic. They also study religious texts and memorize the Qur’an. These schools prepare students for religious study at the post-secondary level, where they can eventually earn the Malaysian Higher Certificate in Religion [148] (Sijil Tinggi Agama Malaysia, STAM).

Malaysian Certificate of Education (Sijil Pelajaran Malaysia, SPM)

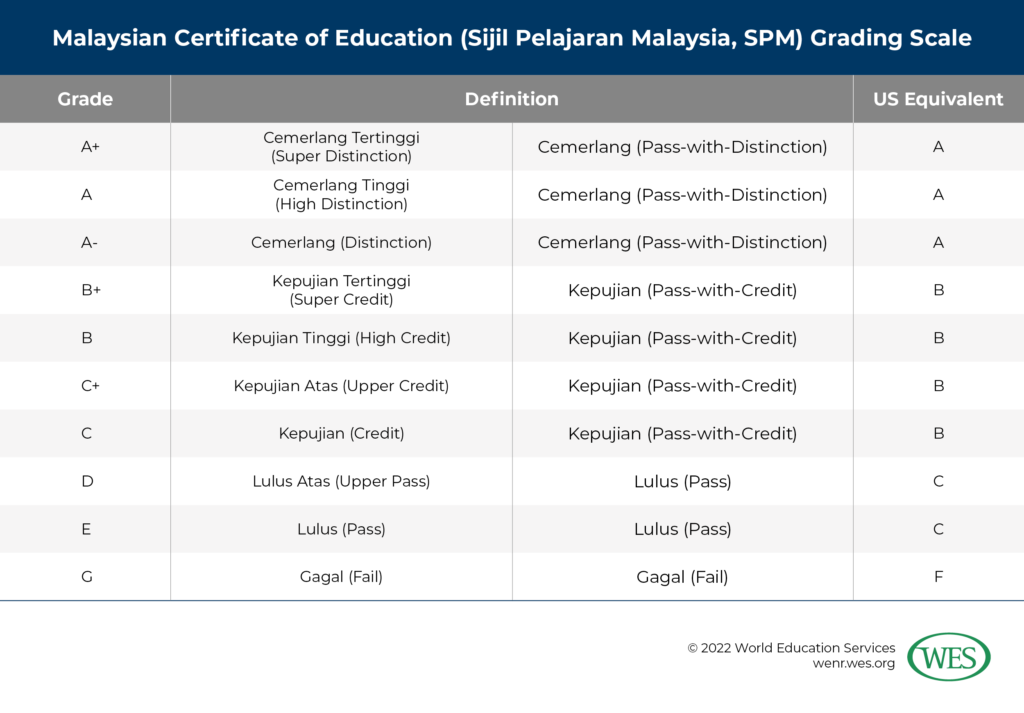

At the end of two years of upper secondary school, students must sit for a national examination, the Malaysian Certificate of Education (Sijil Pelajaran Malaysia, SPM [133]), which is administered by the MOE’s Examinations Syndicate [149] (Lembaga Peperiksaan, LP). The SPM resembles Ordinary Level (O-Level) qualifications awarded by examining bodies in the U.K. and in former British colonies like Singapore and Hong Kong.

Students are required to sit for exams in six compulsory subjects: Bahasa Melayu, English language, Islamic or moral education, history, mathematics, and science. They also sit for a number of elective subjects according to their course of study. Depending on the subject, students take written, listening, or practical examinations. To be awarded the SPM, students must pass Bahasa Melayu.

The aim of the SPM is to prepare students for further study at the post-secondary, or pre-university, level. The SPM is also required for admission to public universities in Malaysia.

Public, Private, and Independent Secondary Schools

Secondary school students can enroll in a variety of types of public and private secondary schools. Among public schools, regular, or daily, national secondary schools (Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan, Harian) are the most popular, enrolling 1.8 million [114] students in 2022. Other public secondary schools [136] include:

- Full Boarding Schools (Sekolah Berasrama Penuh, SBP)

- Vocational Colleges and Technical High Schools (Kolej Vokasional dan Sekolah Menengah Teknik)

- Government-Aided Religious Schools (Sekolah Agama Bantuan Kerajaan, SABK)

- National Religious Secondary Schools (Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Agama, SMKA)

- Sports Schools (Sekolah Sukan)

- Art Schools (Sekolah Seni)

- The Royal Military Academy (Maktab Tentera DiRaja, MTD)

- MARA Junior Colleges of Science (Maktab Rendah Sains MARA, MRSM)

Students can also enroll in private academic, international, or religious secondary schools, as well as Chinese independent secondary schools. In 2022, 60 Chinese independent schools enrolled 79,033 students.

Chinese independent secondary schools have a long history, with some having been founded in the nineteenth century by ethnic Chinese communities. Even today, although open to all Malaysians, these schools continue to attract mostly ethnic Chinese students.

Secondary education at these schools lasts for six years and is divided into two stages: three years of junior middle school and three years of senior middle school. These schools teach in Mandarin Chinese and follow a curriculum developed by the United Chinese School Committees Association of Malaysia [151] (UCSCAM), also known as Dong Zhong. This curriculum draws on the curricula used in Malaysia as well as those used in Taiwan and Mainland China.

At the end of the six years of study, students in Chinese independent secondary schools take the Unified Examinations Certificate (Sijil Peperiksaan Bersama, UEC), administered by UCSCAM.

Although many vocational and private tertiary institutions admit students possessing the UEC, public universities do not. To be admitted to a public university in Malaysia, students possessing the UEC must continue their studies and obtain the SPM. As a result, many UEC holders elect to leave Malaysia to continue their studies in China.

Post-secondary Education (Pendidikan Lepas Menengah)

To be admitted to an undergraduate program at a Malaysian university, students must first obtain a post-secondary, or pre-university, qualification. These qualifications can be obtained from external examining boards, specialized public colleges, and public and private universities.

Form 6 (Tingkatan 6)

Form 6 [152] classes are typically offered at secondary schools or specialized Form 6 academies. They typically last three semesters [153], or one-and-a-half years, and are divided into two stages: lower and upper.

Based on their SPM performance, students admitted to Form 6 are typically streamed into either a humanities or science track. In 2022 [154], 40,311 students were enrolled in Form 6 humanities programs and 4,733 in Form 6 science programs.

Form 6 classes aim to prepare students to take the Malaysian Higher School Certificate [155] (Sijil Tinggi Persekolahan Malaysia, STPM) examination, administered by the Malaysian Examinations Council [156] (Majlis Peperiksaan Malaysia, MPM). To qualify for admission [157] to public universities, students must pass a minimum of four STPM subjects, including General Studies (Pengajian Am).

The STPM examination is similar to the Advanced Level (A-Level) qualifications awarded by examining bodies in the U.K. and in former British colonies like Singapore and Hong Kong.

Students in Form 6 religious classes typically study for one year and take the Malaysian Higher Certificate in Religion [148] (Sijil Tinggi Agama Malaysia, STAM) examination.

Students can also study to earn pre-university qualifications awarded by international examination boards. Both public and private universities accept many of these qualifications, which include the Australian Matriculation (AUSMAT), the Cambridge International General Certificate of Education (Advanced Level), the Canadian International Matriculation Programme (CIMP), and the International Baccalaureate (IB) Diploma Program.

Malaysia Matriculation Program (Program Matrikulasi Malaysia)

Besides Form 6, the Malaysian Matriculation Program [158] also offers a pathway to public universities for some students.

Matriculation programs [159] are widely viewed as the easiest and least expensive way to enroll in public universities. Programs are considered far easier than Form 6 and the STPM, and tuition and room and board are free [160]. Matriculation programs also take less time to complete, with most programs requiring just one year of study.

But they are also difficult to access, especially for non-Bumiputera students. Not only does their popularity mean that competition for open seats is fierce, but an ethnic quota system reserves most seats for Bumiputera students. First established in 1998 [161], these matriculation programs initially reserved seats for Bumiputera students alone. In the years since, little has changed. Today, 90 percent [162] of seats are reserved for Bumiputera students, leaving just 10 percent for non-Bumiputera students.

Currently, 17 matriculation colleges [163] offer matriculation programs. In 2019 [162], 40,000 seats, of which 36,000 were reserved for Bumiputera students, were available in matriculation programs.

Students enroll in one of four majors: accounting (perakaunan), engineering (kejuruteraan), professional accounting (perakaunan profesional), and science (sains). Science and engineering majors are further divided into a handful of specialized streams. Admission requirements [164] vary according to major, with programs open only to students obtaining certain grades in certain subjects on the SPM. Not all matriculation colleges offer every major.

All majors and streams are offered as One-Year Programs (Program Satu Tahun, PST). However, in 2008, a Two-Year Program (Program Dua Tahun, PDT) was introduced for science majors. The PDT is only open to Bumiputera students who do not qualify for admission to the PST.

Students completing the program are awarded the MOE Matriculation Certificate (Sijil Matrikulasi KPM).

University Foundation (Asasi) Programs

Both public and private universities also offer pre-university foundation (asasi) programs, which prepare students for undergraduate study. These programs [165] include basic science and humanities courses as well as more specialized subjects related to the field that students expect to study at the undergraduate level. These programs require the completion of a minimum of 50 credits [166], typically necessitating one year of study, although some extend up to two years.

Today, 12 public universities offer foundation programs [167], many of which restrict access to Malay or Bumiputera students. In 2021 [41], 12,706 students were enrolled in public university matriculation and foundation programs.

Many private universities, including international branch campuses [168], also offer pre-university foundation programs. Unlike matriculation programs, students enrolled in private university foundation programs often pay tuition and other university fees.

Students completing one of these programs are awarded a Foundation Qualification and are eligible for admission to an undergraduate program in a related field of study.

Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET)

Malaysia’s government, like many others around the world, has grown to appreciate the importance of technical and vocational education and training (pendidikan dan Latihan teknikal dan vokasional, TVET) to the nation’s prosperity in recent decades.

Still, troubles persist. Multiple and often poorly coordinated ministries oversee the sector, each applying a different system of quality assurance. Similarly, delivery is fragmented across several different types of institutions, each offering a different set of qualifications.

Malaysian Skills Certification System (Sistem Persijilan Kemahiran Malaysia, SPKM)

The Malaysian Skills Certification System (Sistem Persijilan Kemahiran Malaysia, SPKM) is one of Malaysia’s principal TVET subsystems. Students completing lower secondary school can enroll in a wide range of technical, vocational, and professional training courses and earn one of the following skills qualifications [169]:

- Malaysian Skills Certificate Level 1 (Sijil Kemahiran Malaysia (SKM) Tahap 1)

- Malaysian Skills Certificate Level 2 (Sijil Kemahiran Malaysia (SKM) Tahap 2)

- Malaysian Skills Certificate Level 3 (Sijil Kemahiran Malaysia (SKM) Tahap 3)

- Malaysian Skills Diploma Level 4 (Diploma Kemahiran Malaysia (DKM) Tahap 4)

- Malaysian Skills Advanced Diploma Level 5 (Diploma Lanjutan Kemahiran Malaysia (DLKM) Tahap 5)

These qualifications are administered by the Department of Skills Development [104] (Jabatan Pembangunan Kemahiran, JPK), which is under the Ministry of Human Resources [105] (Kementerian Sumber Manusia, KSM).11 [170] Skills qualifications must conform to the National Occupational Skills Standard (Standard Kemahiran Pekerjaan Kebangsaan, NOSS [171]).

SPKM programs are offered through two methods, the National Dual Training System (Sistem Latihan Dual Nasional, SLDN [172]) the Certified Program Training System (Sistem Latihan Program Bertauliah, SLaPB [173]).

Under the SLDN, 70 to 80 percent of the program is an apprenticeship, providing students industry experience, with just 20 to 30 percent taking place in a Skills Training Center (Pusat Latihan Kemahiran, PLK).

Under the SLaPB, training is mostly conducted at a variety of JPK-accredited public and private skills training institutes [174] (institusi latihan kemahiran), although many programs also include three to six months of Industry Experience (LI).

Among the four [175] public skills training institutes [176] are: