Understanding Transnational Education, Its Growth and Implications

Nick Clark, Editor, World Education News & Reviews

The dynamics of internationalization are changing. Many of the students that traditionally would have traveled overseas to study for an international qualification are now pursuing foreign degrees in their home, or neighboring, countries at local institutions through an array of collaborative arrangements with degree-awarding institutions from major education-exporting countries.

Students in this segment of the international education market, referred to as transnational education (TNE), study for foreign qualifications in any manner of ways. The most commonly understood delivery method is through the international branch campus, but these foreign outposts are responsible for just a tiny fraction of the degrees being delivered by institutions across borders. More common are in-country partner arrangements that might include the franchising, twinning or validating of degree programs to teaching institutions and other organizations by awarding institutions in countries like Australia and Great Britain.

The wide array of transnational delivery options is oftentimes confusing, while issues related to quality control, assessment and student learning outcomes can be opaque. For credential evaluators, this can present problems and a range of questions related to document verification and institutional recognition. In this article, we take a look at the scale of the transnational education market, offer definitions of some of the main delivery methods, and then explore some of the issues that arise for credential evaluators when handling documents from these programs.

The Numbers

Reliable data on the scale of the TNE market are not as readily available as they are for in-country provision to international students, but official figures from two of the biggest innovators in the field – the United Kingdom and Australia – suggest that the market is significant and growing.

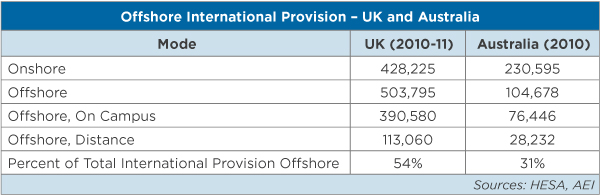

According to data released in January by Britain’s Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA), the number of students studying ‘wholly overseas’ for a UK higher education qualification increased by more than 95,000 in 2011 to 503,795 – 75,000 more than the number of international students that were enrolled at institutions in the UK (428,225) and approximately one-sixth of all students studying for UK awards.

Of those students, 113,060 were enrolled abroad via distance education, 291,745 on programs run in collaboration with a partner organization, 86,670 in ‘other’ arrangements including collaborative provision, and just 12,315 on overseas branch campuses. The Observatory on Borderless Higher Education (OBHE), does note however in a recent report that British universities have nearly doubled their number of branch campuses in the past two years to 25.

The top five countries for transnational education provision of UK qualifications in 2009/10 were: Malaysia (48,255), Singapore (42,715), Hong Kong (24,135), Pakistan (23,570), and Nigeria (16,930). Interestingly, China, the top source of international students in the United Kingdom, ranked sixth for TNE (14,785), while India, the second biggest source of international students, ranked just 16th with 7,350 TNE students.

Overall, more than three-quarters of TNE students (2009/10) pursuing UK qualifications were enrolled at the undergraduate level.

In Australia, almost one third (104,678) of international students studying for an Australian higher education qualification were doing so ‘offshore’ in 2010, according to figures from Australia Education International. Of those, 75,377 were studying on campus and 25,115 via distance learning.

All of the top five nationalities for offshore higher education were Asian: Singapore, China, Malaysia, Hong Kong and Vietnam. As in the UK, the main TNE countries for Australian providers do not necessarily align with trends in the numbers of students travelling to Australia to study. The top five sources of international higher education students in Australia are: China, India, Malaysia, Vietnam and Indonesia.

Over two-thirds of students offshore were studying for Australian bachelor degrees and well over half in the fields of management and commerce.

Not unexpectedly, offshore students are more likely to be studying part time for Australian qualifications (31 percent of the total) than is the case for their peers who have made the financial investment of studying in Australia (10 percent). This statistic points to issues related to the cost of studying and living abroad, in addition to the red tape related to finding work as a foreign student in many host countries.

While there is no official data on the number of students undertaking U.S. degrees overseas, a report released last year by the Institute for International Education shows that joint- and dual-degree programs are becoming an increasingly popular method of internationalization for many universities in the United States. The report found that more American institutions than in any other country reported offering dual-degree programs, with half being offered at the undergraduate level. The United States also leads the way with regards to international branch campuses overseas, with an estimated 78 currently in operation according to the OBHE.

Types of Arrangement

Given the huge number of students enrolled in UK higher education programs overseas it is appropriate that the country’s standards watchdog, the Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education, has very specific guidelines for standards and auditing in the transnational education market. These guidelines are spelled out in Section 2 of the QAA’s Code of Practice for the Assurance of Academic Quality and Standards in Higher Education, first published in 1999 and most recently updated in 2010.

The Appendix to the Code provides a glossary of terms, noting that ‘in the vocabulary of collaborative arrangements, many words are given different meanings or are used in different ways by different institutions and in different countries. This is a source of actual and potential confusion.’

Given the potential for confusion in developing, understanding and monitoring transnational education programs, a commonly understood typology would be of benefit to all parties involved.

The following is a selection of terms related to the provision of transnational education taken from three well-thought-out sources in the TNE space:

- A Guide to UK Higher Education and Partnerships for Overseas Universities by the UK Higher Education International and Europe Unit (July 2011)

- What are International Dual, Joint Degrees by Kris Olds (Jan 2011)

- Code of Practice for the Assurance of Academic Quality and Standards in Higher Education by the QAA (2010)

Some of the more common arrangements include:

Articulation – An awarding institution reviews the provision of another organization and deems that the curriculum is of an adequate standard for the award of specific credit leading to direct entry into year two, three or four of the specified program at the awarding institution. These arrangements occur most frequently at the undergraduate level. Examples might include 2+2, 3+1, and 2+1 agreements. Students are aware from the outset that they will qualify for advanced standing at a particular institution upon completion of the partner section of the program.

Branch Campus – A foreign degree-granting location of an institution of higher education. As simple as this definition seems, what exactly constitutes a branch campus seems to have become something of a moving target.

Distance Delivery or ‘Flexible and Distributed Learning’ (FDL, as defined by the QAA) – The QAA uses the phrase ‘flexible and distributed learning’ to include both distance learning and e-learning. In both cases, the awarding institution delivers courses – through independent-learning materials or via distance technology (online) – directly to the student without the need for a partnering institution.

Franchising – A process by which an awarding institution agrees to authorize another organization or institution to deliver (and sometimes assess) part or all of one (or more) of its own approved programs. Often, the awarding institution retains direct responsibility for the program content, the teaching and assessment strategy, the assessment regime and quality assurance. The teaching institution will often lack its own degree-awarding powers, hence the need to franchise – or ‘affiliate’ – itself with a degree-awarding institution.

Joint Degree – One program, taught collaboratively by two or more universities with periods of study at each location. One award with crests/logos of participating institutions.

Dual Degree – As above, but with the award of two or more certificates and transcripts. Each institution has responsibility for its own degree.

Progression Agreement or Sequential Degrees – Students studying at named partners are entitled to enroll in and complete a second, related program at the second partner institution once they have earned a specified first degree and met the admission requirements.

Degree Validation– The partner delivers its own programs to its own students at its own centers; however, the awarding institution validates the programs because the partner either lacks degree-awarding powers or else the power to make awards at a particular (for example, graduate) level or in a given disciplinary area. Students receive an award certificate with the awarding institution logo alongside the partner’s name, and in some cases, logo/crest.

Course-to-Course Credit Transfer, Transfer “Contracts” – Pre-arranged recognition of the equivalency of specific courses at one institution to the corresponding course at another institution.

QAA Audits of Transnational Provision

The principals and guidelines underpinning the foreign partnerships of UK institutions are overseen by the Quality Assurance Agency. The watchdog agency conducts reviews of oversees provision on a country-by-country basis, publishing its findings and recommendations through reports on its website.

The following are brief synopses of the QAA’s more recent reports. These reports give an idea of the type and scale of transnational provision occurring in some of the bigger and more important Asian education markets.

Singapore

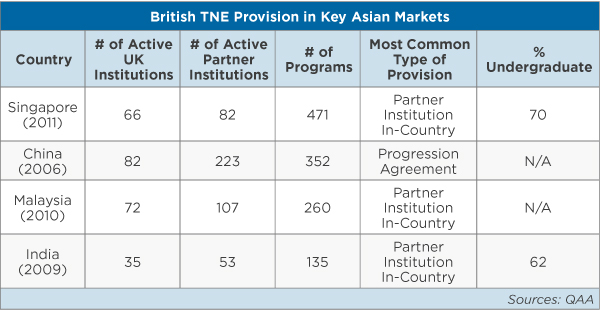

According to the 2011 audit by the QAA into collaborative arrangements between British institutions and Singaporean partners, there were a reported 471 TNE programs, ‘of which the vast majority (89 percent, or 417) were studied entirely in Singapore with a partner institution (in-country). Six percent (29) of these programs led to a qualification from the Singaporean institution, which gave advanced standing to a program offered by the UK institution (articulation). The remaining five percent of the programs were studied partially with a partner institution in Singapore and partially in the UK, or offered by the UK institution to students in Singapore with learning support provided by a Singaporean partner (distance learning).’

Business and administrative studies accounted for 62 percent of the programs (292), followed by creative arts and design (56), mathematics and computer sciences (46) and engineering (19).

Seventy percent of the programs were offered at the undergraduate level, 24 percent at the master’s level and three percent were doctoral degrees. A total of 66 UK institutions were either planning to start or had one or more existing links with 82 Singaporean partners. The vast majority of Singaporean partners were privately funded.

China

The QAA is currently undertaking a review of transnational higher education in mainland China where the awarding body is a UK higher education institution. The results are yet to be published, but according to the findings of a 2006 audit, upon which the current review is building, there were 82 UK higher education institutions that had or were intending to establish links with 223 Chinese institutions to deliver a UK higher education award.

The most common links were found to be under progression agreements, where Chinese students undertake one or two years of undergraduate study at a Chinese institution before progressing to a final one or two years of study at the UK (awarding) institutions. In a few cases, students graduate with qualifications from both institutions. There were 58 UK institutions involved in 168 links under progression agreements, with 140 at the undergraduate level. These accounted for over a third of all links. Advanced standing arrangements for admission to a UK institution for students with specific Chinese qualifications was the next most common arrangement (50 links), followed by foundation programs prior to admission (22 links) and direct delivery of programs in China (20 links).

The most common offerings were business and administrative studies (38 percent), engineering (25 percent), and mathematical and computer sciences (10 percent). Teaching is performed by both Chinese and UK staff, but largely with English as the medium of instruction. An estimated 11,000 students were studying in China for a UK award in 2005-06, which compares to the 50,755 Chinese students that were in the UK studying that same year.

Malaysia

Data from the Higher Education Statistics Agency show that Malaysia is the largest market for UK transnational higher education provision, with almost four times as many Malaysia-based students studying on UK higher education programs than the number of Malaysian students in the UK. Malaysia’s aspirations to become a regional hub for higher education in Southeast Asia may raise demand still further, according to the QAA.

The QAA’s spring 2009 survey of UK higher education institutions found that 72 UK institutions had a total of 260 collaborative links with 107 Malaysian partners leading to the award of a UK qualification. Of those, 40 percent (102 links) concerned programs which were studied entirely in Malaysia with a partner institution, and a further 36 percent (94 links) were articulation agreements. The remaining programs were classified as twinning arrangements where study occurs partially with a partner institution in Malaysia and partially in the UK, and distance learning. In addition, there were two campuses owned and operated by a UK institution: The University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus and Newcastle University Medicine Malaysia. The most common fields of study were business and management (75 links), engineering (46 links) and law (24 links).

The QAA performed a series of site audits looking more closely at 10 institutions’ processes for creating and managing collaborative provision. From these, the QAA surmised some valuable lessons:

- Ensure policies and procedures for managing collaborative provision are clear and comprehensive, and then stick to them

- Have a written agreement and keep it up to date

- Prioritize access to effective electronic learning resources for students outside the UK

- Maintain close working relationships with the partner, but do not rely on one person to do it

- Where relevant, be absolutely clear about professional accreditation

- Give the partner’s students and staff effective and timely feedback on their performance

- Provide support for English language development, even where English is already widely spoken

- Involve the partner’s staff and students in program management and development as the partnership matures.

India

The QAA’s 2009 report on Indian TNE provision found that there were 35 UK universities with active collaborative arrangements leading to the award of UK qualifications in 2007-08. These institutions were collaborating with a total of 53 Indian partner organizations, covering 135 programs. Most universities (22, or 63 percent) had links with only a single partner in India, but others had multiple partners.

Approximately half the programs were studied entirely in India through partnerships with local institutions, and another 6 percent were distance-learning programs. Other programs involved students transferring to the UK, either through articulation arrangements (28 percent) or twinning arrangements (10 percent).

Of programs offered, 62 percent were at the undergraduate level, 37 percent at the master’s level, and just one program at the doctoral level. Business and management accounted for 30 percent of collaborations, while engineering and technology accounted for 20 percent. In every partnership, the UK university was the sole awarding institution.

The QAA surmised that ‘UK universities demonstrated a willingness to comply with in-country regulations, but, although there was a general appreciation that the situation was complex, there was by no means a full or common understanding of the requirements.’

Implications for Credential Evaluators

The process for evaluating foreign academic credentials involves establishing that the awarding institution is recognized or accredited, confirming that the credential was issued by the relevant institution, establishing an equivalency in U.S. terms, and determining credit and grade equivalents.

Recognition of the academic institution is key. It must be determined where the institution is located, what the appropriate recognition mechanisms are in the host country, if the institution is duly recognized by the appropriate authorities in the country where it is located, and if so if that recognition includes offering instruction and degrees in other countries.

Given that institutional recognition is key in establishing credential equivalency, transnational provision presents complications when a degree is awarded by an overseas institution for teaching performed by an institution that is not authorized to award degrees, or is offered in a country that doesn’t have recognition mechanisms for foreign programs. What, for example, does an evaluator do when students submit records for incomplete study from a degree program validated by an institution recognized in its home country but taught through a non-recognized institution in the host country? Until the degree is conferred, the courses taken essentially have no academic merit.

At World Education Service, we currently take credentials at face value after they have been authenticated and it has been established that a recognized or accredited institution issued them. We assume that if an institution is recognized in its home country it can be trusted to deliver programs of comparable quality abroad. By the same token, we assume that the teaching and learning that take place abroad are equivalent and that the institutions that award the degrees are the guarantors of programs offered abroad.

However, under the current environment of proliferating transnational programs, arrangements between teaching institutions and degree granting institutions are oftentimes opaque and hard to figure out. How a degree granting institution maintains standards or assures quality is often unclear, especially in cases where institutions license their curricular content to third-party providers in different countries. In such cases, we often have to rely on transcripts issued by what are essentially non-accredited teaching institutions.

Our role at WES is to interpret and validate foreign qualifications to help individuals study, work or migrate to the United States. Under no circumstances do we want to stigmatize students who attend legitimate transnational programs, but at the same time we do not want to ‘launder’ sub-standard programs by equating them to home-taught programs of a higher quality. We need reliable indicators that the credentials we receive represent equal value to those being issued from home-taught programs.

These issues bring up questions related to the role of accrediting agencies and standards watchdogs in home countries. Do recent scandals such as those involving Chinese transfer students at Dickinson State University suggest that home accrediting bodies should play a greater role in monitoring the transnational offerings of the institutions they accredit, or should quality assurance procedures be the sole domain of the awarding institution?

Given the growing size of the transnational market, we believe there is a need for agreed-upon terminology and standards and a far greater deal of transparency. We are currently assessing our own internal procedures for evaluating transnational degrees based on an understanding of domestic regulations in host teaching countries and oversight procedures in major awarding countries in the hope that we can evaluate as fairly as possible the awards being offered in this brave new world of international education. In future articles, we hope to share some of our findings and recommendations.