When countries began to close their borders to slow the spread of COVID-19 in 2020, universities had to adjust quickly. Almost overnight, institutions shifted to the virtual classroom, allowing them to reach students anywhere in the world, even those overseas.

This experiment with remote learning gave many colleges and universities their first substantial experience running a transnational education (TNE) program, a type of program in which education is delivered in a country other than that in which the degree is awarded. With the pandemic reshaping the international education landscape, TNE programs could grow increasingly common.

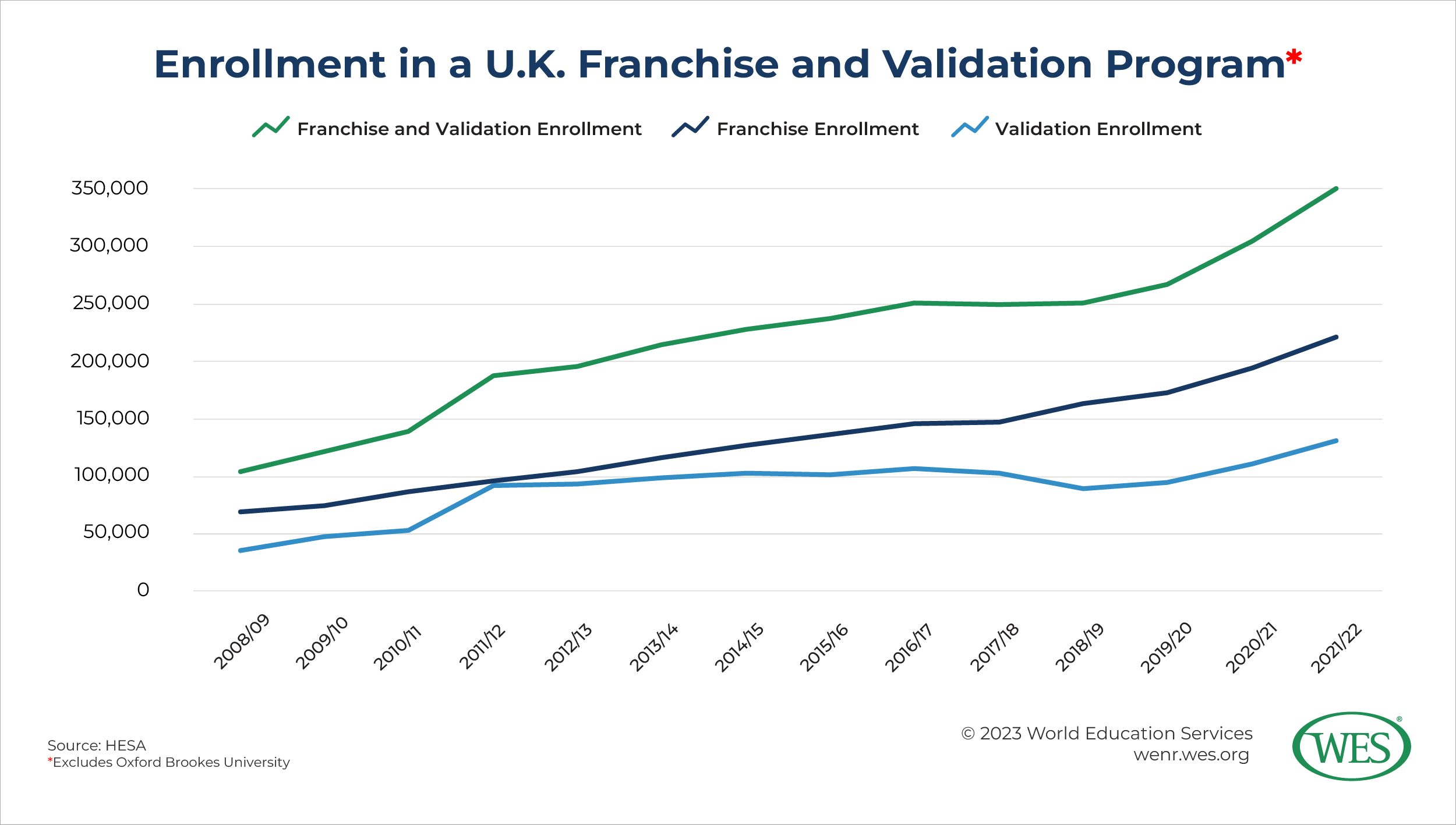

In the United Kingdom, long a TNE pioneer, the popularity of these programs had been growing swiftly even prior to the pandemic. Enrollments were rising especially fast among franchise and validation programs, which allow students to earn a degree awarded by a recognized international college or university while studying entirely at a local institution in their home country. In 2021/22, two-thirds [2] of all students studying in a U.K. TNE program were enrolled in a franchise or validation program.

To their proponents, franchise and validation programs can help reputable higher education institutions reach students who are unable to travel overseas to study. Through partnerships with institutions abroad, universities running these programs can provide the same high-quality, in-person education to students outside the country as they can to students studying on their home campuses. What’s more, these programs, like all TNE arrangements, can promise institutions a healthy return on a relatively modest investment.

But franchise and validation programs also come with their own unique risks. In the eyes of their critics, behind their proliferation, the profit motive reigns supreme. The pursuit of profit can exacerbate the many logistical and supervisory challenges that always accompany cross-border initiatives. In extreme cases, this greed can put more than just a single program’s quality at risk; it can even threaten the reputations of the participating academic institutions themselves.

This article explores these popular programs, examining their content and structure, their relation to partner institutions in multiple countries, and their implications for international credential evaluators. It also charts the development and growth of TNE arrangements, with a focus on those originating in the U.K., the world’s leading TNE exporter, examining the factors driving their spread and the incentives that can compromise their quality. In a world where more and more of life can be conducted at a distance, understanding the intricacies of these programs will be vital to international education professionals working to ensure that students from around the world can access a high-quality education.

Defining Franchise and Validation Programs

But what are franchise and validation programs?

Defining them precisely can be difficult. Although they share certain common features, the specific details of franchise and validation arrangements vary from program to program and from institution to institution.

This is because negotiations between higher education institutions located in two or more countries ultimately determine the specifics of every franchise and validation program. Although many major institutions have developed standardized templates for use in all TNE partnerships, the negotiation process still results in a variety of program arrangements. For example, profit sharing provisions, as well as the division of responsibility between partner institutions for educational delivery, the setting of admissions standards, the assessment of student performance, and more, often differ widely between programs.

Still, all franchise and validation programs do share certain characteristics. For example, both franchise and validation programs involve cooperation between at least two institutions located in different countries. One of these institutions, the exporting institution, always awards the final degree, while the other, the importing institution,1 [3] always teaches the academic program. Additionally, all franchise and validation programs are required to comply with the relevant national regulations of both countries.

Franchise Programs

International franchise programs [4] involve a partnership between a sending university (or franchisor) and an international provider (or franchisee) in which the sending university authorizes the international provider to deliver the sending university’s academic degree program. The sending university always awards the final degree.

As noted above, the two partner institutions divide responsibility for the program between themselves. Typically, the exporting university designs the academic program, develops the curriculum and learning materials, sets admission standards, assesses student performance, and oversees program quality. The importing institution is typically responsible for administrative processing, marketing, and teaching. In most cases, the exporting institution collects a previously determined portion of the course fees paid by the student to the teaching institution.

The franchise arrangement is intended to guarantee that the program taught by the importing institution is essentially the same as that taught at the sending institution. The admission requirements, content, length, and structure of franchise programs mirror those of degrees offered at the sending institution’s home campus.

For example, INTI International College Subang [5] in Malaysia (the franchisee) delivers a three-year Bachelor of Arts with Honours in Business Administration which is awarded by the University of Hertfordshire [6] in the U.K. (the franchisor). The admission requirements, course structure, and length of the program [7] taught in Malaysia are identical to those of the same program [8] taught at the University of Hertfordshire’s home campus.

Although franchise programs at the first-degree level are the most popular, enrolling around three-quarters (72.3 percent) of all students in 2021/22, non-thesis postgraduate programs also attract a sizable number of students (23.5 percent). For example, the Management Development Institute of Singapore [9] (MDIS) teaches a Master of Science in Data Science and Business Analytics, which is awarded by the University of Plymouth [10] in the U.K.

Validation Programs

Validation [11] is a partnership arrangement with a similar division of operational responsibilities, and it is often categorized [12] as a subdivision of franchise programs. However, in the case of validated programs, the importing institution (or validated provider) is typically also responsible for setting admissions standards and assessing student performance. More significantly, the importing institution is also in charge of designing the academic program, developing curricula and syllabi, and overseeing program quality.

The exporting institution (or validating institution) validates the academic program, verifying that the academic standards of the program taught at the importing institution are equal to the standards of programs offered by the exporting institution. The sending institution also awards the final degree.

For example, Nottingham Trent University (NTU) in the U.K. and Pearl Academy in India have together offered validation programs since 1995. A 2009 report [13] from the U.K.’s Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (QAA) described their collaboration as involving “NTU in providing validation services to its partner, under which the University verifies the academic standard of each program and confers the awards, while responsibility for the quality of provision is delegated to Pearl.”

Unlike with franchise programs, the exporting institution in a validation arrangement typically does not offer the same program on its home campus. As the curricula of these programs do not need to mirror those of programs taught at the exporting institution, importing institutions possess considerable flexibility when designing a validation program. This allows them to design programs that meet the needs of the local community, the institution, and their students, and leads to a greater diversity of program types than is the case with franchise arrangements.

For example, the Emirates Aviation University [14] in the United Arab Emirates developed and teaches a Bachelor of Engineering with Honours in Aircraft Maintenance that is validated and awarded by Coventry University [15] in the U.K. The program’s form is unconventional and is not offered on Coventry University’s home campus. Its admission requirements—the possession of a professional license or certificate—are non-academic; and its length—two years, part-time—is a sharp departure from what is typical of undergraduate engineering degree programs taught in the U.K. Its unique form results from the aim of the validated institution, the Emirates Aviation University, which is to offer currently employed aircraft maintenance engineers the opportunity to “extend their knowledge” and “consolidate their professional experience with a recognized academic degree” without leaving work.

As is the case with franchise programs, most students enrolled in validation programs study at the first-degree level (75.2 percent in 2021/22). However, non-thesis postgraduate programs (23.4 percent) are also popular. For example, besides the undergraduate program just mentioned, Coventry University also validates and awards other programs taught by the Emirates Aviation University, such as an 18-month, part-time Master of Business Administration [16] in Aviation Management.

Evaluating Franchise and Validation Credentials

Franchise and validation programs present unique challenges to international credential evaluators.

For one, official documents often make identifying these programs difficult. For franchise and validation programs, the exporting institution issues both the final degree certificate and the transcript of academic records. These documents often differ little from those issued for programs taught entirely at the exporting institution’s home campus, making it hard to differentiate franchise and validation programs from the other programs offered by the exporting institution.

Still, issued documents often do include a few subtle indications that can help evaluators identify these programs. While it is unlikely that the degree certificate includes much pertinent information, the academic transcript will often indicate the name of the overseas partner institution or the location of study.

Even with that information in hand, more research will often be needed. Academic transcripts rarely indicate the exact nature of the TNE arrangement (whether franchise, validation, or another type) and, if they do, the terminology they use may differ from that used at institutions elsewhere.

This information can be vital for determining the structure of the TNE program and making accurate equivalency decisions. For franchise programs, which mirror programs offered on the home campus, the degree awarded will be equivalent to that awarded upon completion of the same program taught at the exporting institution’s home campus. For validation programs, which differ from programs offered at the home campus, considerations of program structure, such as admissions requirements and years of study, will help inform equivalency decisions.

Other challenges concern the recognition status of academic programs and partner institutions. In many cases, the accreditation status of the two partner institutions differs. Frequently, the exporting institution will be accredited and authorized to award degrees by the relevant accreditation agency in its home country, while the importing institution, although authorized to operate, will lack similar recognition from the body responsible for accreditation where it is located. Despite this divergence, the accreditation status of the program and institution in the exporting institution’s home country is decisive, as the sending institution is responsible for verifying the academic standards of the program and awarding the final degree.

The United Kingdom: A TNE Pioneer

Institutions that export TNE programs, including franchise and validation programs, are largely located [17] in Western, Anglophone nations. Among these, the U.K. is far and away the most significant. In 2021/22, more than half a million international students living outside the U.K. (532,460) were enrolled in a U.K. TNE program, which, besides franchise and validation programs, includes distance learning programs and programs taught at a U.K. international branch campus. This figure is more than three-quarters (78.3 percent) of the number of international students studying at institutions located in the U.K. (679,970 [18]), the world’s second-largest destination for international students.2 [19]

As noted above, enrollment in franchise or validation programs accounts for two-thirds (66.8 percent [2]) of all enrollment in U.K. TNE programs. In 2021/22, the number of overseas students enrolled in a franchise or validation program exported by a U.K. higher education institution reached as many as 355,740.3 [20]

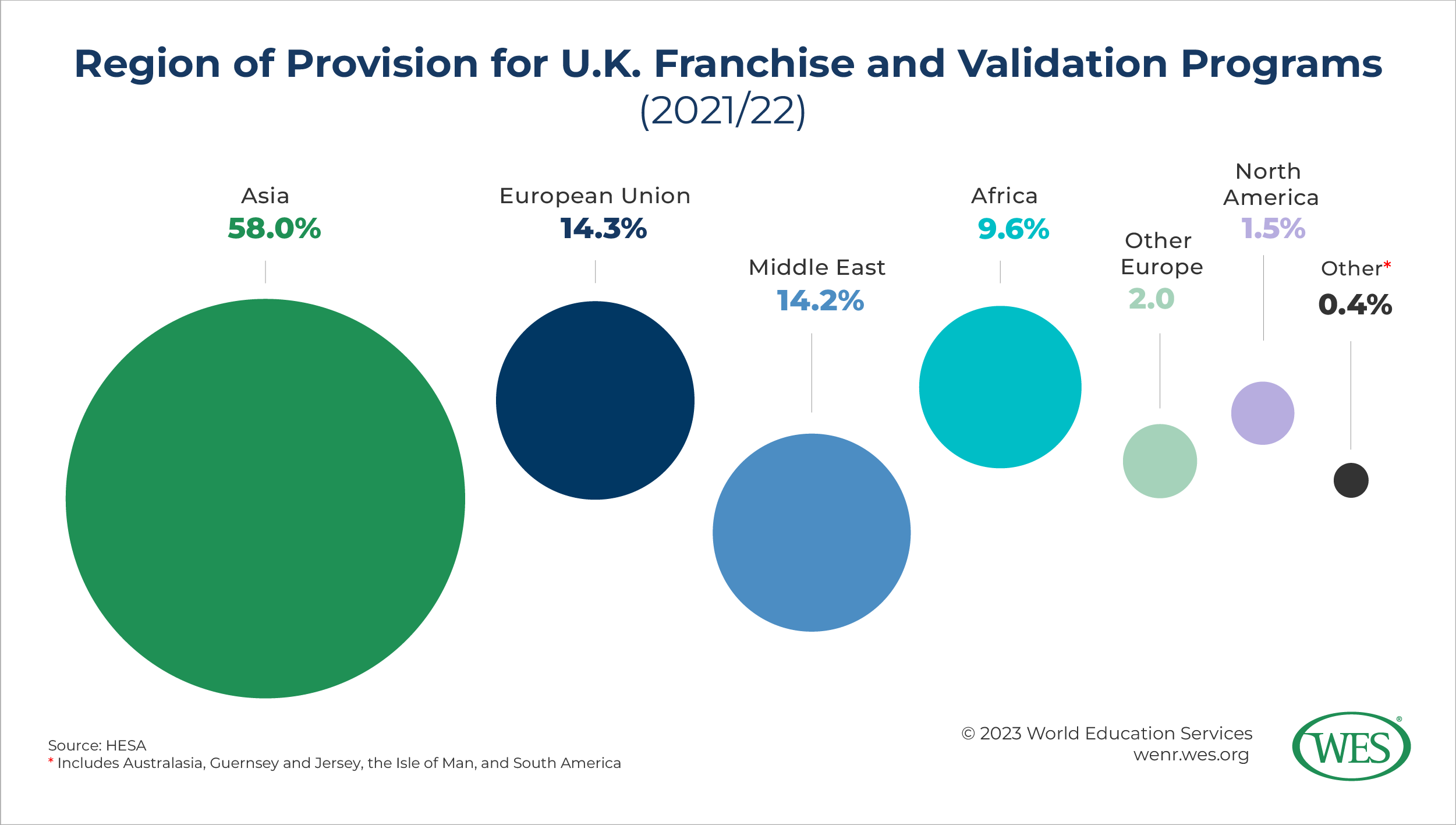

While U.K. institutions have established franchise and validation programs throughout the world, their efforts are concentrated principally in Asia. Students from Asia account for nearly three out of every five students (58 percent) enrolled in a U.K. franchise and validation program. Although country-specific data are unavailable, large numbers of students from China, Malaysia, Singapore, and Sri Lanka likely enroll in these programs. In 2021/22, students from these countries [22] accounted for 36.2 percent of all U.K. TNE students.

The U.K.’s dominance of international franchise and validation programs reflects the unique history of the country’s higher education system. Prior to the enactment of the Further and Higher Education Act of 1992 [24], domestic validation programs, similar to the international validation programs described above, were widespread in the U.K. The Council for National Academic Awards (CNAA), an erstwhile national degree-awarding authority, validated and awarded degrees for programs taught at dozens of polytechnics and central institutions across the nation, all of which lacked autonomous degree-granting authority. To effectively operate under these arrangements, the validated providers developed [25] “sophisticated quality assurance systems” and institutional competence in “designing curricula and assessment regimes for external audit.”

Following the enactment of the Further and Higher Education Act of 1992, which granted university status and degree-awarding authority to 35 erstwhile validated centers, many of these new universities were able to repurpose the competencies developed as validated providers to the task of validating external programs. For example, Oxford Brookes University, one of the post-1992 universities [26], quickly grew into one of the U.K.’s largest TNE exporters. In 2018/19,4 [27] Oxford Brookes University enrolled 260,155 students in TNE programs—39 percent of all students enrolled in U.K. TNE programs that year, and more than six times the number enrolled at the University of London (40,675),5 [28] the U.K.’s second-largest TNE exporter.

Universities in the U.K. were further spurred to establish franchise and validation programs internationally by the dissolution of the Soviet Union. As former Eastern bloc countries opened to the West, the European Union, through the Trans-European Mobility Program for University Studies [29] (TEMPUS), made funding available to EU universities to help institutions in former Soviet countries develop modern academic programs and curricula. That external funding encouraged U.K. higher education institutions to franchise their degree programs to institutions in Eastern Europe.

Globally, TNE and franchising and validation programs received a further boost following the adoption of the General Agreement on Trade in Services [30] (GATS), a legal agreement of the World Trade Organization [31] (WTO) that went into effect in January 1995. Binding on all WTO members, the GATS [32] provided a transparent regulatory framework governing international trade in services, including educational services,6 [33] clarifying for both parties in franchising and validation agreements the external regulations they need to comply with.

However, it was in the years immediately preceding and following the Great Recession that TNE and franchise and validation programs really began to take off. In the second quarter of 2008, the U.K.’s economy [34] went into recession. Negative economic growth continued for 15 months, ending in the second quarter of 2009, although economic growth remained anemic for far longer. As elsewhere, the recession took its toll on U.K. government coffers, and the amount of public funding [35] appropriated for universities was slashed.

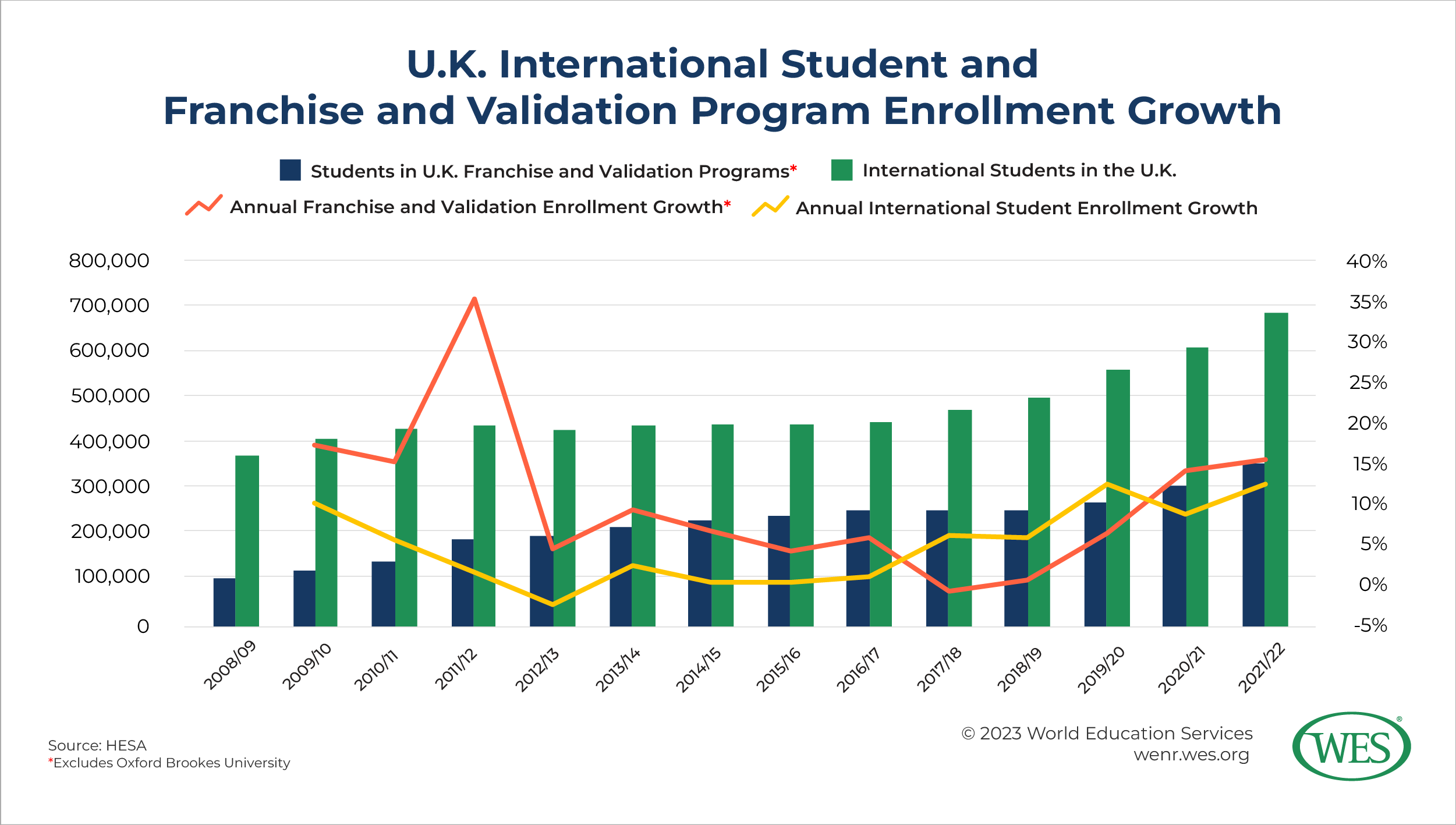

The global recession also left many prospective international students and their families unable or unwilling to invest large sums in an expensive overseas education. As a result, the recruitment of international students—whose tuition fees could help fill the funding gap created by falling public expenditure—to the U.K. slowed following the 2009/10 academic year. International student enrollment numbers declined even in 2012/13.

Despite declining public funding and slowing international enrollment at home, growth in the number of overseas students enrolled in a U.K. franchise or validation program began to surge. While the number of international students studying in the U.K. grew by 84 percent between 2008/09 and 2021/22, the number of overseas students studying in a U.K. franchise or validation program (not including Oxford Brookes University) grew by an astounding 240 percent over the same period.

Growth was fastest in the years immediately surrounding the Great Recession. Between 2008/09 and 2011/12, the number of overseas students studying in a U.K. franchise or validation program (not including Oxford Brookes University) grew by 82 percent, rising from 103,695 to 188,296.

The Pursuit of Pupils, Prestige, and Profit

That the dramatic growth of U.K. TNE enrollments coincided with a decline in public funding and a slowdown in on-campus international student recruitment highlights the importance of revenue-generation in the decision to establish TNE programs, especially among exporting institutions. A 2014 research report [37] commissioned by the U.K. Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS) found that many institutions pursued TNE arrangements to “provide and/or diversify in-country opportunities for international students and thereby reduce exposure to reliance on direct recruitment to the UK campus.”

In fact, in regard to franchise programs, critics have gone so far as to allege that “the entire purpose [38] of the operation is to make money.” U.K. government officials have even explicitly promoted TNE and franchise and validation programs as a means of boosting both university revenues and the value of the country’s education exports. Speaking [39] at the 2012 annual conference of the Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE), David Willetts [40], then Minister for Universities and Science, lauded the international “sharing of educational technologies” and “degree validation” as “one of Britain’s great growth industries of the future.” In the 2021 update to the U.K.’s International Education Strategy [41], the Department of Education identified addressing “market barriers to the growth of UK education exports” as a key priority, noting that “this will help facilitate the expansion of TNE.”

Official encouragement appears to have benefited the sector handsomely. Government statistics [42] estimate that revenues from all U.K. TNE activities expanded by 112.9 percent between 2010 and 2020, when they reached £2.3 billion. Over the same period, total U.K. education-related exports grew more modestly, increasing 57.5 percent to £23.3 billion.

Another important factor motivating higher education institutions to establish franchise and validation programs internationally is a desire to boost their international presence and brand name. In today’s globalized world, the importance of institutional internationalization is widely recognized [43]. A strong international presence and reputation can be an important marketing tool, helping institutions distinguish themselves from others competing for the same pool of increasingly important student tuition fees. The low level of initial investment required, and the minimal risk of financial loss make franchise and validation programs an attractive option for higher education institutions looking to expand their international profile.

The motivations of importing partners complement those of exporting institutions. Partnering with a recognized overseas institution allows these providers, many of which do not have the authority to award domestic degrees, to offer prospective students the opportunity to obtain a prestigious international qualification. Acting as a stamp of international approval, franchise and validation programs can significantly boost the ability of teaching institutions to attract fee-paying students.

On a more general level, franchise and validation programs, like all TNE programs, offer importing countries, many of which are experiencing a rapid increase in higher education demand, a means of quickly increasing their educational capacity and, ideally, the quality of their domestic higher education systems. These programs may also help to slow brain drain, as students studying entirely in their home countries may be less likely to emigrate after they complete their studies.

Quality Assurance Challenges

But franchise and validation programs do not always fulfill the hopes of their most ardent supporters—they may even frustrate their promises of easy financial gain. Some researchers allege that disillusionment [44] over the actual profitability of franchise and validation programs is growing among exporters. They cite the BIS report referenced above, which found that per student fees for these programs pale in comparison to those collected from students studying at the institution’s home campus.7 [45] But more disconcerting may be the disillusionment of exporters and importers in the capacity of these arrangements to undergird reputable, high-quality educational programs.

Quality concerns have long plagued franchise and validation programs, and the two models are considered to be among the riskiest TNE arrangements [46] when it comes to quality assurance. The profit interests of both parties pose a particularly acute risk. These interests place a premium on increasing enrollment numbers and tuition fees over the maintenance of quality standards.

While institutions must also manage the negative effects of profit interests on programs offered at home, they face unique challenges when addressing those that impact programs offered across international borders. There, two distinct bureaucratic apparatuses must act honestly and in concert, while long distances can complicate even heightened oversight processes and help conceal pertinent information.

Profit interests can compromise program oversight and quality in many ways. For example, a desire to limit monetary expenditure may lead the exporting university to underinvest in the oversight of importing institutions. The desire to increase enrollment numbers and tuition fees may lead importing institutions to ease admissions standards and turn a blind eye to cheating and poor student performance. The desire to maximize revenue may also lead both partner institutions to ignore investment in educational infrastructure and learning technologies.

Furthermore, while details on the institutions providing franchise and validation programs are not readily available, the stronger the brand of the importing institution, the lower its need to collaborate with an international partner. In fact, in Malaysia [47], recognized universities are not permitted to enter international franchise arrangements, and any institution achieving full university status must end all of its existing franchise arrangements. As a result, less-than-reputable institutions may be overrepresented among the group of importing institutions offering franchise and validation programs. However, as teaching institutions lose a powerful marketing tool when TNE partnerships end, exporting institutions can leverage the continuation of partnership agreements to induce teaching institutions to improve quality.

Areas of Concern: The International Viewpoint

For exporting institutions, the challenges of ensuring the quality of education of distant overseas programs are especially evident in the following areas:

- Local recruitment of administrative staff. Exporting institutions that fail to sufficiently supervise the marketing and promotional activities of teaching institutions leave room for bad actors to misrepresent the program and the exporting institution to prospective students. Additionally, outsourcing control over the admissions process of teaching institutions can open the door to corruption and bribery. In the case of franchise programs, it can also lead to the application of different admissions standards to students applying to the program at home and those applying to the program overseas. Theoretically, both sets of students should possess the same qualifications, but if administrators at the importing institution lower admission standards, they could admit inadequately prepared students to the franchise program.

- Local recruitment of academic staff. In franchising and validation arrangements, faculty hired from among the local population are responsible for teaching. Exporting institutions that fail to effectively oversee the hiring or vetting of local faculty risk awarding degrees for programs taught by unqualified or inadequately prepared staff. Also, even if local staff teach the same curriculum as that offered on the home campus, exporting institutions need to ensure that faculty possess the appropriate teaching “ethos [48].” For example, overseas faculty need to be able to utilize learning methodologies similar to those used on the home campus. In validation programs where local faculty are often responsible for assessing student performance, insufficient oversight may also create space for fraud and cheating.

- Learning materials, equipment, and facilities. Agreements between institutions to establish a franchise or validation program rarely require either partner to increase spending on learning resources. Still, exporting institutions need to guarantee that importing institutions possess the educational resources that are available on the home campus and necessary for a quality education, such as labs and libraries. Furthermore, in validation programs, as the importing institution designs the curricula and syllabi, at times in the language of the country where the importing institution is located [49], exporting institutions need to ensure that the staff they employ to evaluate proposed programs actually possess the requisite competencies.

- Responsiveness to student needs. Great geographical distances and the delegation of student-staff interaction to the importing institution raise significant questions about the ability of awarding institutions to hear student voices and respond to student feedback. For franchised programs, which should in principle be identical to programs offered on home campuses, questions about the relevance of international curricula are also a recurring concern. However, as QAA’s 2019 review [50] of U.K. TNE partnerships in Malaysia found, “most institutions allowed for the franchised provision to be contextualized to address issues relevant to students in Malaysia.”

Quality Assurance Mechanisms

These concerns are more than just theoretical.

The dramatic closure of the University of Wales [51] (UW) following revelations that it partnered with disreputable international institutions exemplifies the risks that lax oversight poses to program quality and institutional reputations. Prior to its dissolution, UW maintained TNE relationships with 130 institutions [52] throughout the world, teaching around 70,000 students at home and abroad. Following reports in the media in 2010 detailing widespread quality issues at many of the university’s partner institutions, the QAA opened investigations into UW’s overseas operations, finding severe deficiencies [53] in its oversight of associated colleges. These and other mounting issues forced the university to close in 2011, almost 120 years after it was founded.

As this example illustrates, inadequate oversight of franchise and validation programs risks the credibility and reputation of both partner institutions. Serious failures to ensure program quality may even damage the reputation of the sending institution’s domestic higher education system as a whole. To protect against these outcomes, higher education institutions and regulatory bodies throughout the world have developed rules and guidelines aimed at ensuring the quality of their nation’s TNE programs.

In the U.K., the Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education [54] (QAA) is responsible for regulating TNE programs. Institutions receiving public funding in the U.K. are bound by the expectations and core practices of the UK Quality Code for Higher Education [55], developed by QAA, which aims to protect “the public and student interest” and champion “UK higher education’s world-leading reputation for quality.” The expectations “express the outcomes providers should achieve in setting and maintaining the standards of their awards, and for managing the quality of their provision.”

To meet these expectations, the Quality Code requires that higher education institutions, when working in partnership with other organizations, have in place effective arrangements to ensure that:

- “the standards of its awards are credible and secure irrespective of where or how courses are delivered or who delivers them”

- “the academic experience is high-quality irrespective of where or how courses are delivered and who delivers them”

To meet these requirements, higher education institutions develop policies and procedures that govern the management and oversight of TNE programs, ideally following the guiding principles [56] established by QAA for partnership arrangements. These procedures typically include everything from an initial evaluation and approval of partnerships to arrangements governing the termination of the contract.

They also include arrangements designed to manage and secure academic standards and quality. For example, Robert Gordon University requires that monitoring and reviewing procedures [57] follow those used for all courses taught at the home campus. Finally, to verify that institutions are meeting the required expectations and engaging in the core practices outlined in the Quality Code, QAA conducts in-country audits [58] of U.K. TNE operations.

The Future of Franchise and Validation Programs

As noted above, enrollment in franchise and validation programs expanded fastest in the years just before and after the Great Recession, before moderating slightly in the years that followed. More recently, however, it has accelerated again. Between 2019/20 and 2020/21, enrollment grew 14 percent to a new high of 305,680 (not including Oxford Brookes University). The context of this latest expansion hardly needs introduction: 2020/21 was the first full academic year that followed the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Although the underlying circumstances are quite different, this latest enrollment surge shares some similarities with the earlier acceleration. Notably, as during the Great Recession, the pandemic severely undermined the ability of international students to travel overseas to study. While closed wallets kept students at home before, closed borders were likely more decisive this time. The subsequent opening of borders may suggest that this latest expansion will be short-lived.

Still, something seems to have changed. While restrictions at most international borders have reverted to their pre-pandemic norm, much else has not. In particular, more and more of life’s daily activities—from working to studying—are conducted at a distance. This shift suggests that the future of franchise and validation programs, as well as that of other TNE programs, may be getting brighter.

The latest HESA data, released just before this article was published, back these intuitions up. Enrollment growth accelerated in 2021/22, increasing 15 percent to 352,610 (not including Oxford Brookes University).

At their best, franchise and validation programs are a synergistic blend of the global and the local, combining the academic, curricular, and pedagogic knowledge of exporting institutions with the cultural, linguistic, and marketing expertise of local partners. At their worst, they make a mockery of both, taking advantage of the gulf that separates global and local institutions to grind out diplomas worth little more than the paper they are printed on. If these programs do flourish in a post-pandemic world, international education professionals will need to help students and institutions sift the good from the bad to ensure that students can access a high-quality education from anywhere around the globe.

1. [59] In both franchise and validation programs, the exporting institution is also referred to as the home, sending, or awarding institution. The importing institution is also referred to as the receiving or teaching institution.

2. [60] The U.K. also collects and publishes—through the Higher Education Statistics Agency [2] (HESA)—the most comprehensive data on TNE programs of all major sending countries. Because of the U.K.’s dominance of TNE programs and the comprehensiveness of its data collection, the discussion of franchise and validation programs that follows focuses on the programs and partnerships that involve U.K.-based higher education institutions.

3. [61] This is the combined, annual total of “overseas students registered at a UK HEI in an arrangement other than distance and branch campus, including collaborative provision” and “overseas students studying for an award of a UK HEI with an overseas partner organization.” These two activities, as defined [62] by HESA’s Aggregate Offshore Record (AOR), are often treated as proxies for franchise and validation programs, respectively. However, it should be noted that these statistical categories are likely very imperfect proxies. A transnational education census [37] which collected data on TNE programs offered by U.K. HEIs in 2012/13 found that the AOR “does not capture the entire landscape of transnational education” and that “Transnational education activity recorded as ‘overseas-registered’ and ‘UK registered’ in the Aggregate Offshore Record does not relate simply to validation and franchise provision, as may have been assumed.” It found that enrollments in franchise and validation programs made up 33 percent of all U.K. TNE programs in 2012/13, against 76 percent for the same year in the AOR, which suggests that using the two abovementioned AOR categories may vastly overstate franchise and validation enrollment. However, it also found that franchise and validation programs, not enrollments, made up 19 percent and 51 percent respectively of all programs categorized as “overseas partner registered” and 48 percent and 17 percent respectively of all programs categorized as “UK registered,” which suggests that franchise and validation programs drive the overall growth trends of these two categories.

4. [63] In 2019/20, Oxford Brookes University changed its reporting practices, a move that resulted in a decline of 256,450 students from that institution alone between 2018/19 and 2019/20. Following the example of Universities UK [64], this article excludes data from Oxford Brookes University where appropriate.

5. [65] Although not a post-1992 university, the University of London’s unique federal structure—the university consists of 17 member institutions—armed it with many of the same competencies. Today, it operates a robust international study system [66], offering mostly distance learning programs to students around the world.

6. [67] GATS applies to four modes of cross-border trade in services. Franchise and validation programs fall under Mode 3 [68], or “commercial presence,” which refers to services supplied through a third party.

7. [69] The BIS report found that student fees remitted to U.K. institutions in 2012/13 from providers of undergraduate franchise and validation programs varied between £300 and £1,350 per student, with higher fees for postgraduate programs.