Chris Mackie, Editor, WENR

The COVID-19 pandemic along with policy changes developed in its wake has pushed tens of thousands of international students to forgo enrollment at colleges and universities in the United States this fall, according to a report on survey results released earlier this week by the Institute of International Education (IIE).

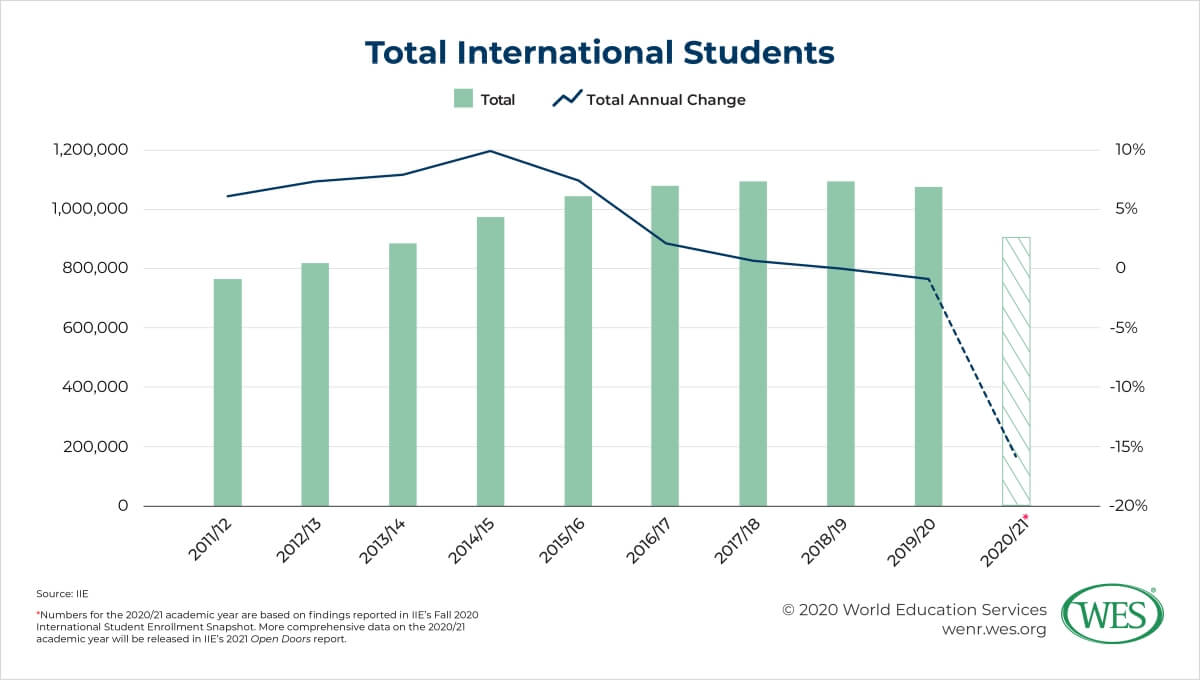

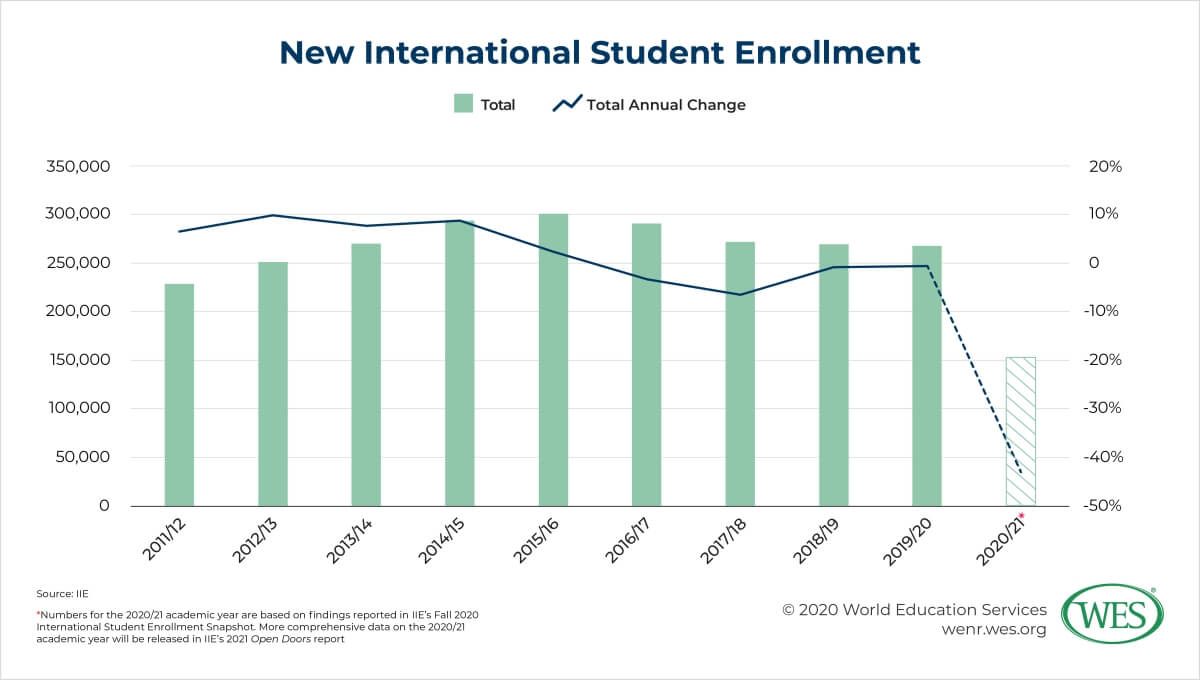

IIE also reported that total international student enrollment declined by 16 percent for fall 2020 at the more than 700 academic institutions surveyed. That figure translates to a loss of around 170,000 international students between this year and last, assuming the remainder of the country’s nearly 3,000 colleges and universities saw similar declines. First-time enrollments of international students fell even more sharply, plummeting a record 43 percent in the fall.

The survey was conducted by 10 higher education associations and published in a report [2] issued by IIE alongside its annual Open Doors report. The analysis includes all international students enrolled in a U.S. higher education institution (HEI) and studying in person in the U.S. or online from the U.S. or overseas.

The survey, a snapshot of the fall 2020 semester, provides the most comprehensive disclosure to date of the depth of the disruption to and transformation of international education caused by the pandemic and shifting federal policies. The survey findings, together with those from the Open Doors report, raise concerns about the extent to which this fall’s declines portend longer-term shifts in mobility. The decrease it reports threatens not only to blow a hole in the budgets of colleges and universities across the country, but to deprive U.S. employers of the top talent they need to power the recovery.

“Staggering but, unfortunately, not surprising”

As governments raced to contain the virus, disruptions to international education quickly multiplied, leading international education experts to predict sharp global declines in international student enrollment for the upcoming academic year. Travel restrictions and canceled flights limited international mobility, while widespread job losses likely reduced the pool of prospective students able to afford an expensive overseas education.

In the U.S., these global disruptions were exacerbated by a unique confluence of public health, social, and political conditions. Commenting on the declines disclosed in the fall snapshot survey, Ted Mitchell, president of the American Council on Education, told the Wall Street Journal [3] that they were “staggering but, unfortunately, not surprising.”

U.S. international education began to feel the pandemic’s effects late in the spring 2020 semester [4], as the virus’s rapid spread drove colleges and universities to close campuses and send students, both domestic and foreign, home. Safety measures introduced around the same time, aimed at stemming the outbreak, further complicated the ability of international students to study in the U.S. In March, the U.S. Department of State suspended routine visa services [5], including the processing of student visas, at all U.S. embassies and consulates. A phased resumption [6] of visa services began in July. The closures likely upset the plans of prospective international students in particular, and partly account for the dramatic decline in new international student enrollment.

Early and ongoing evidence of the inability of the U.S. to control the virus likely also weighed heavily on the minds of international students and their families. To date, COVID-19 has killed more than a quarter million people [7] in the U.S., the highest death toll in the world. A recent QS survey [8] found that most prospective international students had reconsidered where to study as a result of a country’s response to the pandemic. Respondents to that survey also ranked the U.S. response to the pandemic as among the worst of all popular study destinations. According to a World Education Services (WES) survey [9] conducted in August, nearly three-quarters of prospective international students were extremely or moderately concerned about their health in traveling to the U.S.

Domestic social and political unrest, prompted by the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis and manifested most notably in nationwide demonstrations protesting police brutality and systemic racism, have likely led international students to question whether the U.S. is still a safe and welcoming study destination. Forty percent of international students responding to the WES August survey indicated that the country’s social and political environment made them less interested in studying in the U.S.

The Trump administration’s “America First” policies and rhetoric, which intensified following the coronavirus outbreak, have likely had a similar effect on the perceptions of international students. The government has consistently depicted immigrants and international visitors, including international students, as a threat to the country’s economy and national security. Recently, the administration narrowed eligibility requirements for H-1B work visas, a popular pathway to a post-graduation career for many international students, and proposed a new rule that would eliminate open-ended visas for international students [10]. Government officials dispute [11] any assertion that the administration wants to deter international students from enrolling in the U.S., maintaining that the country continues to welcome them.

Another significant policy change occurred just before the start of the fall semester. While partially walking back a July directive requiring all international students studying entirely online to leave the country, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) still revised previous guidance to ban new international students with a fully online course load from coming to the country. This change likely accounts for a shocking 72 percent decline in the number of new international students physically present in the U.S. More than half of new students, 51 percent, are studying online from outside the country, a radical change in the international education landscape.

“No going back”: Education, Support, and Recruitment Transformations

The fall snapshot survey also revealed the transformative impact of the pandemic on educational delivery, support services, and recruitment and outreach. As expected, institutions expanded their use of digital teaching technologies first adopted late in the spring 2020 semester. The survey found that 99 percent of institutions were offering online courses—11 percent were offering only online courses, while 88 percent were offering a hybrid mix of online and in-person instruction. Among all international students, not just new international students, one-fifth were studying remotely at a U.S. HEI from overseas. Less than 1 percent did the same in fall 2019.

The pandemic has also transformed support services, driving institutions to develop novel approaches to the promotion of international students’ health, welfare, and educational achievement. A large percentage of institutions reported hosting virtual networking events for international students (76 percent), and adjusting online course schedules and teaching methods to accommodate international students (49 percent).

With college dormitories emptying out [12], more and more universities are providing international students with on-campus accommodations: More than three-quarters report offering on-campus or other housing options. Institutions also introduced safety measures for students, faculty, and staff on campus, including restrictions on on-campus events and social gatherings, mask mandates, and reduced class sizes.

Despite the fall semester’s steep international enrollment decline, institutions did not abandon their international recruitment and outreach efforts—64 percent earmarked funds for these efforts at the same level or higher than before the pandemic—they just altered them. Large percentages still report organizing recruitment events (74 percent) and conducting campus tours (54 percent); only now, they are all held online. Reporting by the Chronicle of Higher Education [13] suggests that the adoption of virtual recruitment practices extended the reach of academic institutions far beyond what was possible with in-person visits. As one international admissions officer told the Chronicle, because of the effectiveness of these practices, there will likely be “no going back” to previous international recruitment efforts.

The report also uncovered a growing interest among colleges and universities in the “backyard” recruitment of international students [14] already present in the U.S. A significant portion of respondents reported recruiting at U.S. high schools (56 percent) and community colleges (44 percent). While backyard recruiting presents a potentially promising source of international students, another report recently released by IIE [15] suggests that these sources may be drying up as well. It found that international secondary enrollments had fallen 15 percent since their peak in 2016. Enrollment from China—the largest source of international students at both the secondary and post-secondary level—fell even further, declining 30 percent over that period. The pool of potential recruits at community colleges and in non-degree programs, such as intensive English language programs, appears to be shrinking as well. Enrollment in associate programs [16] (-10.4 percent) and non-degree programs (-6.6 percent) fell far faster than in bachelor’s programs (-1.5 percent) and graduate level programs (-0.9 percent).

Economic Repercussions

The international enrollment declines outlined in the survey come as U.S. HEIs are already facing enrollment crunches and revenue shortfalls. Data from the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center [17] show total post-secondary enrollment falling over 3 percent; freshman enrollment is down 13 percent. Given the heavy reliance of colleges and universities on income earned from university housing and auxiliary on-campus fees, the nearly universal adoption of remote learning is also likely cutting into institutions’ bottom lines.

As a result of these revenue losses, institutions are struggling financially. Preliminary federal data suggest that HEIs are shedding jobs [18] at an unprecedented pace. Since the outbreak, colleges and universities have laid off a tenth of their employees. As in the larger economy, these cuts have hit the lowest paid workers hardest [19].

International student declines likely account for a disproportionate percentage of the revenue losses at many institutions. Although international students make up only a small proportion of all university learners—less than 6 percent in 2019/20—they are far more likely to pay full tuition fees than domestic students. One recent study [20] estimated that international students account for around 14 percent of total tuition revenues, contributing around $20 billion annually in tuition and related fees.

The financial repercussions of the decline will extend far beyond university balance sheets, impacting both the national economy and local communities [21]. At the national level, the decline will exacerbate pre-pandemic losses. NAFSA: Association of International Educators recently updated its International Student Economic Value Tool [22] to include estimates of international student contributions to the U.S. economy during the 2019/20 academic year. For the first time since NAFSA inaugurated the tool in 2008, the total contribution of international students to the U.S. economy declined, falling over 4 percent; their contribution to job creation fell even further, declining over 9 percent. Unsurprisingly, these declines track the international student enrollment trends for the pre-pandemic, 2019/20 academic year.

International students who have graduated from a U.S. HEI are also an important source of high-skilled labor for the country’s employers. As participants made clear during a social media forum hosted by WES [23], U.S. innovation and technology depend on the skills and expertise of people born outside the country.

Open Doors 2020: A Glance at the Pre-pandemic International Education Landscape

While the pandemic prompted an exceptional decline in international student enrollment, a more modest downward trend already existed prior to the outbreak. IIE’s comprehensive Open Doors report [24], released at the same time as the fall 2020 snapshot survey, details enrollment trends for the 2019/20 academic year, prior to the virus outbreak in the U.S. The report revealed that for the first time in more than a decade, total international student enrollment [25] fell, dropping nearly 2 percent in 2019/20 from the year before.

New international student enrollment [27] declined as well, falling 0.6 percent. While this year’s decline caps four years of new enrollment declines, its relatively low level suggests that, at least prior to the pandemic, these enrollments were beginning to stabilize. In 2017/18, the first full academic year following the inauguration of President Trump, new international student enrollment declined by 6.6 percent.

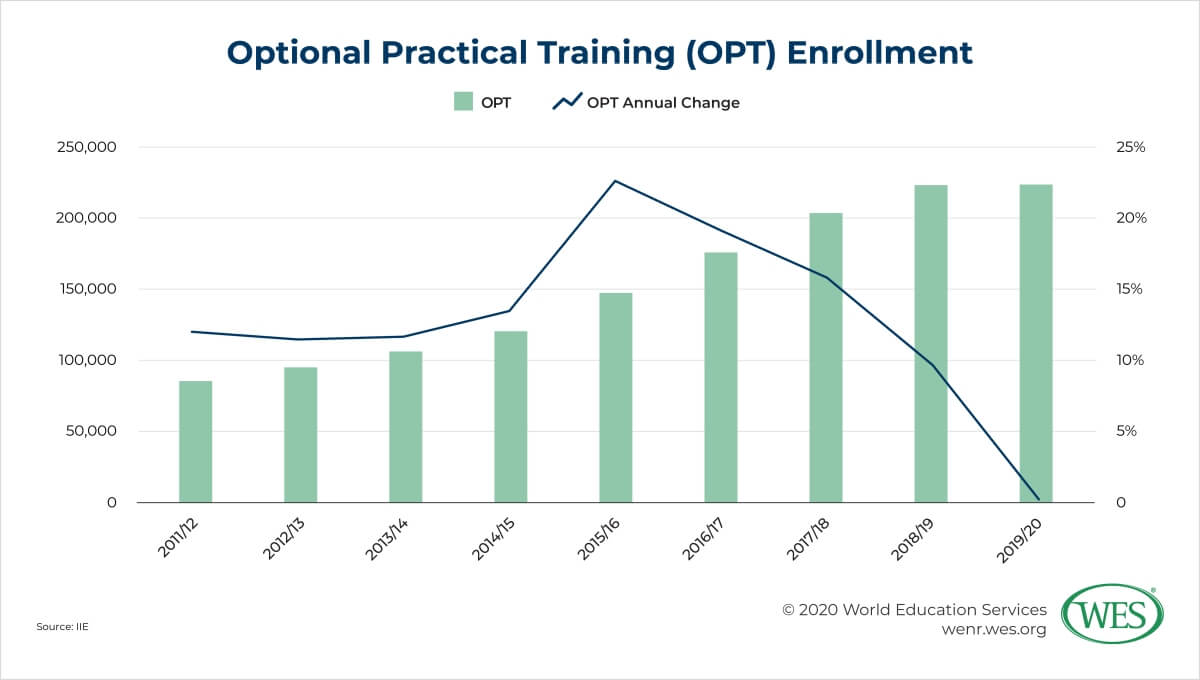

The report also found a sharp slowdown in the growth of participants in the Optional Practical Training (OPT) program, which allows international students to work for up to three years in a field related to their course of study. After years of double-digit growth, OPT participation in 2019/20 remained largely the same as it was the year before, growing just 0.2 percent.

The Trump administration’s efforts to restrict people born outside the U.S. from participating in the economy have often indirectly affected, and sometimes specifically targeted, the OPT program. Recent efforts have included highly publicized discussions of policies that would restrict the program [29], and increased oversight and enforcement actions [30] aimed at program participants. The OPT program has become an increasingly important part of U.S. international education, with participation buoying overall international student numbers [31] in recent years.

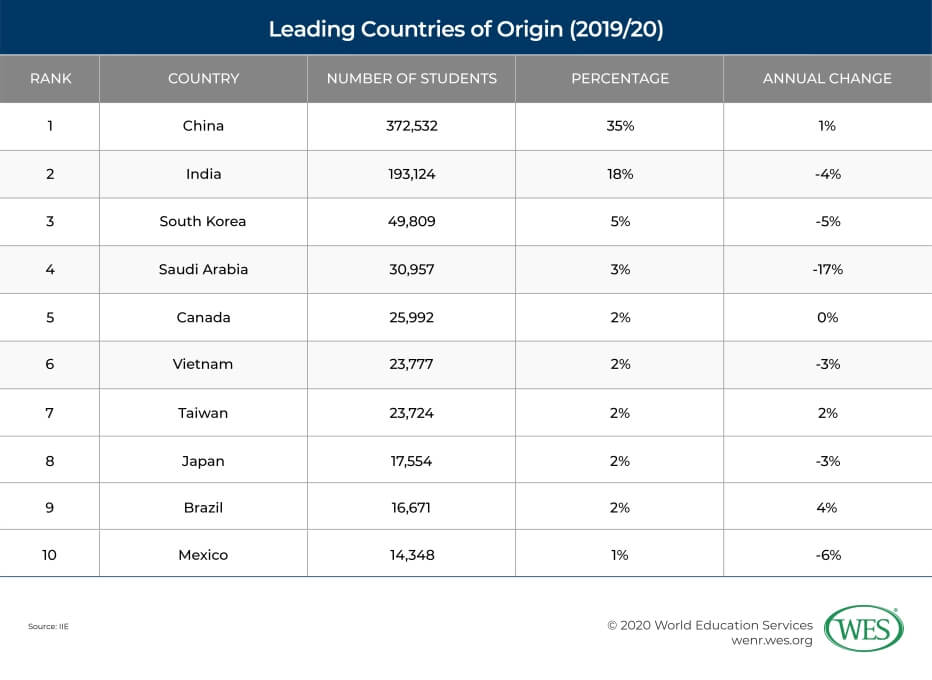

China remained the U.S.’s top source of international students in 2019/20, although growth was minimal. India, 42 percent of whose students participated in the OPT program last year [33], saw sizable declines, contracting 4.4 percent.

Among the top 10 sending countries, Saudi Arabia, still reeling from cuts to a large government scholarship program, saw the sharpest decline, falling 16.5 percent. Brazil continued to recover from the initially disruptive suspension of a popular international student scholarship program in 2015 [34], growing 3.8 percent. Still, even in Brazil, which saw the highest level of growth among the top 10 sending countries, growth slowed sharply from the previous year. In 2018/19, Brazilian enrollments grew by nearly 10 percent.

Looking Ahead to a Post-pandemic Future

Referring to the fall 2020 declines, Allan E. Goodman, president of IIE, stated [36] “We’ve never had a decrease like that.” Reflecting on IIE’s more than 100 years of experience, he continued: “What we do know is when pandemics end, there’s tremendous pent-up demand.” When that happens, he predicted, we will be “dealing with surges of students that have deferred.” IIE’s own data back up that assertion, at least in the short term, and suggest that international student enrollment will rebound immediately after the health crisis subsides. Institutions responding to the fall 2020 snapshot survey reported that nearly 40,000 international students had chosen to defer their enrollment.

Farther out from that, the outlook becomes less clear. While many prospective international students are certainly planning to wait out the pandemic before enrolling, it is unlikely that enough will do so to make up for this year’s dramatic losses. Based on the number of new international students enrolled in 2019/20, this fall’s 43 percent decline in new enrollments translates to a loss of around 115,000 students, far more than are identified in the report as planning to defer. And although its depth and cause are new, this year’s decline is not entirely an outlier: New international student enrollments have declined every year since 2015/16. This means that institutions have long failed to replace graduating international students with new students, a fact partially obscured by the delayed impact of new enrollment declines on total international student numbers. Total international student enrollments fell as a result of declining new enrollments for the first time in 2019/20, a trend that would have likely continued in 2020/21 and beyond, even in the absence of a pandemic.

U.S. HEIs also face growing competition from other countries, a prospect that threatens to chip away at its share of all international students. WES’s August survey of prospective international students—all of whom had previously expressed interest in studying in the U.S.—found that nearly two in five were considering studying in other countries because of the pandemic. U.S. institutions may also have less leeway than those in other countries to raise prices to cover revenue losses during the pandemic-induced economic downturn. Past economic slowdowns, such as that occurring during the Great Recession, forced institutions to raise tuition fees to cover income losses. Given the U.S.’s already notoriously high tuition fees, it’s unclear how much increase international students can bear.

Still, a number of factors may signal a more promising future. Experts expect [37] President-elect Joseph R. Biden Jr. to embrace HEIs and international students and to quickly roll back many of the Trump administration’s restrictive regulations. U.S. colleges and universities are also well aware of the importance of international students, not just to institutional finances but to the U.S. economy and society as a whole. Many HEIs have established student and faculty exchange programs and research partnerships with institutions around the world, ensuring a slow but steady flow of international talent to U.S. campuses. Spurred by the pandemic’s disruptions, even more have developed innovative teaching and recruitment tools and techniques which have granted them access to more students in more places than ever before. And to many international students, the breadth and depth of the education, training, and research opportunities available at U.S. colleges and universities is unmatched by that of any other country. Although we cannot lose sight of the challenges ahead, these considerations inspire a cautious optimism toward the years to come.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of World Education Services (WES).