The Proposed Elimination of “Duration of Status”: A Threat to International Student Mobility

Chris Mackie, Editor, WENR

In a year of uncertainty for international students interested in studying in the United States, another policy proposal threatens to upend international student enrollment at U.S. universities. In a major reversal, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) proposed replacing “duration of status” with fixed admission periods, a move that would limit the amount of time international students can stay in the U.S. on a student visa to a maximum of four years. For some, visas would be limited to just two years. Students needing additional time to complete their studies would have to petition and receive approval from United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) for an extension.

A briefing note on the proposal from Penn State Law’s Center for Immigrants’ Rights Clinic and the Presidents’ Alliance on Higher Education and Immigration warned that the rule, if implemented, would “constitute the largest changes to regulation of international students and scholars in 20 years.”

Administration officials say the change to the duration of status rule is necessary to combat visa fraud, high overstay rates, and threats to the nation’s security. But international education experts, advocates, and educators allege that the proposal is arbitrary, burdensome, and impractical, and that it reinforces the impression that the U.S. does not welcome international students. With the rule expected to threaten the ability of the U.S. to attract and retain international students, these advocates and organizations have rallied to press for student visa policies that would better serve students, universities, and the country.

“Who’s going to take that risk?”

The “duration of status” admission period for student visas currently allows otherwise in-status international students to remain in the U.S. until they complete their studies or practical training. The proposed rule, which was published in the Federal Register on September 25, would, by contrast, limit student visas to a maximum of four years (or, in the most restrictive cases, two), a restriction that DHS describes as aligning with “the normal progress for most programs that nonimmigrants should be making.”

But international education experts question that assertion. They point to a number of programs that require more than four years to complete, such as doctorates, joint bachelor’s and master’s degree programs, and certain medical residencies. And students hoping to gain practical experience through the Optional Practical Training (OPT) and Curricular Practical Training (CPT) programs would need even more time.

Data also suggest that even for programs that can be completed in four years, “normal progress” for most students involves a longer period of study. In the 2015/16 academic year, more than half of first-time bachelor’s students needed more than four years to complete their degrees, according to data from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES).

Advocates fear that fixed admission periods could leave many current and prospective international students uncertain about whether they will be able to remain in the U.S. long enough to complete their studies. “If you set up a system where no one can be guaranteed more than four years in this country, who’s going to take that risk?” Doug Rand, a senior fellow at the Federation of American Scientists, is quoted as asking in an Inside Higher Ed article.

Rand also highlighted the “extraordinarily narrow” grounds that would be used to adjudicate petitions for extensions. Under current regulations, Designated School Officials (DSOs), who are appointed by a student’s institution and approved by the USCIS, can extend a student’s stay if they determine that the student is making normal academic progress and maintaining visa status. But the proposed rule would transfer authority to render that decision to USCIS, which would approve extension petitions only for “compelling academic reasons,” medical emergencies, or extraordinary circumstances outside a student’s control, such as the coronavirus pandemic.

University leaders worry that the determination of “compelling academic reasons,” an as yet ill-defined concept, especially by an agency lacking familiarity with typical academic study, will result in arbitrary denials and force students to leave midstream.

Others worry that the proposed rule would place an unmanageable burden on students, colleges, and even on USCIS itself. Currently, extension requests for international student visas can take more than seven months to process. With DHS estimating that the new rule would require USCIS to process hundreds of thousands of extension of stay (EOS) requests for international students each year, that time is likely to increase. Long delays could turn away current students and scare off prospective applicants. The more than $1,000 that DHS estimates some students would need to spend on extension petitions—for legal costs, filing fees, and medical examinations—is likely to have the same chilling effect.

DHS also estimates that training and implementation of the new rule would cost colleges and universities hundreds of millions of dollars over the next decade. But academic institutions contend that these estimates fall significantly short of the cost of compliance. DHS’s estimates leave out additional time spent advising students, system and process updates, and tuition losses from projected declines in international student enrollments, among other costs. With colleges and universities already projecting significant financial losses from pandemic-related disruptions, shouldering the costs of the new rule could prove a heavy lift to many institutions.

Two-Year Visa Limits: Essential for Visa Compliance, or Arbitrary and Invasive?

DHS time and cost estimates also leave out the cost of complying with E-Verify, an online system managed by DHS that allows companies to check the eligibility of their employees to work in the U.S. The proposed rule would limit the visas of international students enrolled in institutions that do not participate in E-Verify to two years.

DHS believes that participation in E-Verify indicates a willingness “to go above and beyond to ensure compliance with immigration law.” But immigration advocates say that the regulation is a back-door attempt to get institutions to participate in a costly and controversial program. DHS’s own estimates show that, in 2012, participation in E-Verify cost businesses around 13.5 million work hours, while inaccurate results have cost workers their jobs.

The two-year limit would also apply to students from countries with an overstay rate exceeding 10 percent, a move DHS hopes will help combat visa fraud. But experts quickly pointed out that this regulation disproportionately impacts students from African nations, long a target of the Trump administration’s travel restrictions.

Research from the National Foundation for American Policy (NFAP), published shortly after the proposal was announced, also uncovered deep flaws in the data and analysis that DHS relied on to determine overstay rates. The study found that in addition to quantifying actual overstays, the overstay data measured “unrecorded departures,” which in 2016 accounted for more than half of all reported overstays. In a webinar co-sponsored by the Presidents’ Alliance and World Education Services (WES), Stuart Anderson, executive director of NFAP, was unequivocal in his evaluation of the DHS’s use of these reports: “overstay reports should not be used for policy purposes.”

The proposed rule would also limit to two years the visas of international students from countries designated as state sponsors of terrorism: Iran, North Korea, Sudan, and Syria. The two-year limit would also apply to students at non-accredited institutions, in English language training programs, or in programs that “pose a national security risk.”

The limitations will increase the frequency of interactions between international students and immigration officers, a measure administration officials believe is necessary to ensure visa compliance. But experts argue that DHS has failed to adequately justify the changes proposed. Not only has DHS overestimated the prevalence of problems the new system is intended to rectify, such as high overstay rates, it has also underestimated the ability of the current system to address these concerns.

Colleges and universities contend that international students are already closely monitored through the Student and Exchange Visitor Information System (SEVIS). Current regulations already require that institutions submit to SEVIS information relevant to DHS in determining whether a student is likely to comply with visa regulations, thereby allowing DHS to actively monitor the visa compliance of international students. “An individual committed to disappearing into the country after failing to attend classes would already be flagged by the current SEVIS system or would not be worried about submitting an extension application,” Anderson writes in a column in Forbes. “The rule would only affect students with a genuine interest in continuing to study in the United States.”

“Not welcome in the United States”

The rule will also further solidify a growing impression that the U.S. is not open to international students. Esther Brimmer, executive director and CEO of NAFSA: Association of International Educators, stated that the “complicated and burdensome” proposal sends a “message to immigrants, and in particular international students and exchange visitors, that their exceptional talent, work ethic, diverse perspectives, and economic contributions are not welcome in the United States.”

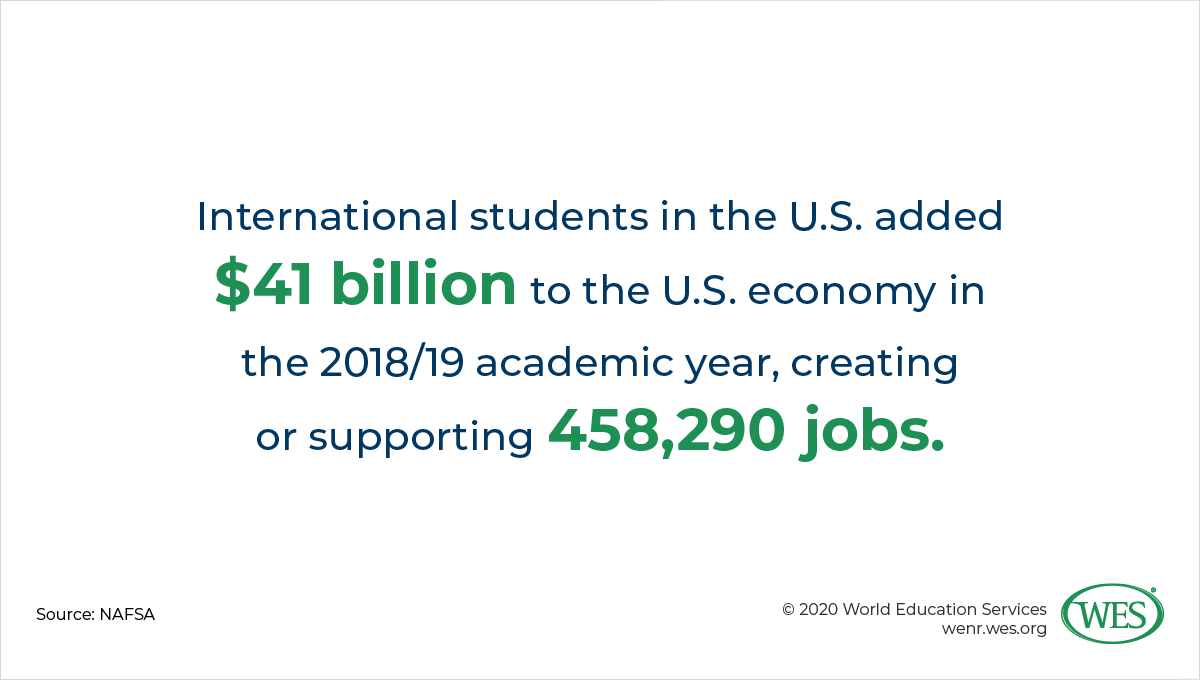

These factors have observers concerned that the new proposal could accelerate an already sharp decline in international student enrollment and jeopardize the significant contributions international students make to universities, local communities, and the national economy. In the 2018/19 academic year, international students injected more than $40 billion into the U.S. economy, creating or supporting almost half a million jobs, according to NAFSA. The Bipartisan Policy Center estimates that international students pay around $20 billion in tuition and ancillary fees to U.S. academic institutions each year. Given their significant contributions, the rule would be a “massive self-inflicted wound” according to Doug Rand, “if it actually goes into effect, which one can reasonably hope it never does.”

The International Education Community’s Rapid Response

For the time being, the rule remains a proposal. The public comment period, during which organizations and individuals can submit feedback to DHS, is set to end on October 26, a little over a week before a presidential election that will likely have significant implications for international students.

In the meantime, international education experts, organizations, and educators have rallied in opposition to the rule. More than 20,000 comments have been submitted to DHS since the proposal was published—a quick survey of the comments suggests that nearly all express disapproval. Many organizations have developed tools and resources to help academic institutions and other interested organizations and individuals advocate on behalf of international students. NAFSA published a page on its website dedicated to sharing information and resources related to the proposal. The Presidents’ Alliance has assembled materials to help interested partners craft effective public comments.

Although the proposal will not result in any immediate changes, Dan Berger, an immigration lawyer, worries that this policy, like others announced by DHS, will “feed uncertainty and concern” among international students, driving them to “increasingly look elsewhere.” International education advocates hope that their efforts can keep the eyes and aspirations of these students firmly set on the U.S.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of World Education Services (WES).